Abstract

Background

Mammographic density and certain histological changes in breast tissues are both risk factors for breast cancer. However, the relationship between these factors remains uncertain. Previous studies have focused on the histology of the epithelial changes, even though breast stroma is the major tissue compartment by volume. We have previously identified lumican and decorin as abundant small leucine-rich proteoglycans in breast stroma that show altered expression after breast tumorigenesis. In this study we have examined breast biopsies for a relationship between mammographic density and stromal alterations.

Methods

We reviewed mammograms from women aged 50–69 years who had enrolled in a provincial mammography screening program and had undergone an excision biopsy for an abnormality that was subsequently diagnosed as benign or pre-invasive breast disease. The overall mammographic density was classified into density categories. All biopsy tissue sections were reviewed and tissue blocks from excision margins distant from the diagnostic lesion were selected. Histological composition was assessed in sections stained with haematoxylin and eosin, and the expression of lumican and decorin was assessed by immunohistochemistry; both were quantified by semi-quantitative scoring.

Results

Tissue sections corresponding to regions of high in comparison with low mammographic density showed no significant difference in the density of ductal and lobular units but showed significantly higher collagen density and extent of fibrosis. Similarly, the expression of lumican and decorin was significantly increased.

Conclusion

Alteration in stromal composition is correlated with increased mammographic density. Although epithelial changes define the eventual pathway for breast cancer development, mammographic density might correspond more directly to alterations in stromal composition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Assessment of the risk of development of invasive breast cancer has recently become a significant problem. This is partly due to the recognition that invasive breast cancer can be prevented by mammographic detection and the treatment of earlier pre-invasive breast lesions [1, 2]. These lesions have been defined by epidemiological, histological and molecular observations and comprise progressive morphological changes in breast epithelium that might parallel the process of evolution towards invasive carcinoma [3, 4].

Mammographic density is a risk factor for breast cancer and is attributed to alterations in the composition of breast tissue [5, 6]. Previous studies seeking to understand the biological basis of mammographic density have focused on associations with epithelial changes [7–10]. However, the major tissue component in breast is stroma, and stromal alterations are also a well recognized component of benign and pre-invasive breast lesions. Furthermore, although breast cancer is a direct manifestation of alterations in the expression of multiple genes and cellular pathways within the breast epithelial cell, it is now recognized that perturbations in stromal–epithelial interactions might also influence tumorigenesis and progression through direct effects on growth factor pathways and indirect effects mediated through cell adhesion and structure [9–12].

We and others have previously shown that distinct genetic alterations can occur in the stromal compartment of breast tumours [13–15]. We have also shown that the small leucine-rich proteoglycans (SLRPs) lumican and decorin are a highly abundant component of breast tissue stroma and that altered expression of stromal proteins is associated with tumour progression and outcome [16, 17]. These SLRPs might be important in both stromal integrity and growth factor pathways through their influence on fibrillary collagen cross linking and, at least for decorin, the ability to bind to growth factors such as transforming growth factor-β and growth factor receptors such as epidermal growth factor [18–21].

We therefore wished to examine the relationship between mammographic density, breast tissue composition and expression of stromal proteins, to establish whether the increased risk attributed to increased mammographic density might reflect stromal alteration.

Materials and methods

Study cohort and mammographic density assessment

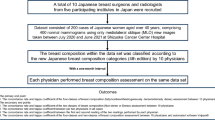

An initial cohort of potential study cases was identified by chart review and comprised patients over 50 years of age who received a screening mammogram at the Manitoba Provincial Screening Program between 1996 and 2000 that had led to a subsequent breast biopsy at either St Boniface Hospital or the Health Sciences Center, Winnipeg, Manitoba, to remove a mammographically detected lesion. Original screening mammograms were then reviewed and the location of the lesion that prompted the subsequent biopsy was identified. The surrounding breast tissue distant from the lesion was then assigned a mammographic density score by using a previously described semiquantitative scale [9, 22]. With this scoring system the percentage of the breast which is composed of radiographically dense tissue is assessed in six categories: 0%, 0–10%, 10–25%, 25–50%, 50–75% and 75–100%.

Pathology reports from an initial cohort of 127 cases were then reviewed to identify all cases in which the biopsy had been a lumpectomy or mastectomy and the eventual pathology had been some form of benign or pre-invasive breast disease. All core and local excision biopsies with limited tissue sample size, as well as cases with invasive carcinoma, were eliminated. Finally, all cases with an intermediate mammographic density score of 25–50% (category 3) were eliminated to ensure that the final study cohort of 62 cases comprised cases that could be sub-classified into two distinct subgroups.

Histological assessment

For each case two tissue blocks corresponding to the specimen margin were identified from the pathology report. This was to ensure that these would be representative of breast tissue distant from the lesion. Sections stained with haematoxylin and eosin were cut from these blocks and used for histological review to confirm that these comprised breast tissue distinct from the principal lesion in the specimen. Additional sections were cut for immunohistochemical analysis of lumican and decorin expression. For each section several parameters were assessed by semiquantitative scoring, including (1) the overall percentage of collagenous stroma within the tissue section (range 0–100%), (2) the average density of collagen or fibrosis (scored as low = 1, intermediate = 2 or high = 3), (3) the extent of peri-ductal fibrosis scored with a 40× objective microscopic field by the extent of collagenous stroma relative to the margin of a duct or duct-lobular unit (less than one high-power field scored 1; less than two high-power fields scored 2; more than two high-power fields scored 3), and (4) the numbers of ducts and duct-lobular units counted at 10× objective magnification within the tissue section, divided by the area of the tissue section (in mm2)

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on paraffin sections as described previously [16]. In brief, sections (5 μm thick) were cut, de-paraffinized, cleared and hydrated in Tris-buffered saline (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, containing 150 mM NaCl) and then pretreated with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes to remove endogenous peroxidases. Non-specific binding was blocked with normal pig serum, 1:10 dilution (Vector Laboratories S-4000). Tris-buffered saline was used between steps for rinsing and as a diluent. Primary antibody against lumican was applied at 1:400 dilution overnight at 4°C, followed by biotinylated secondary pig anti-rabbit IgG, 1:200 dilution (DAKO) for 1 hour at 22°C (room temperature). Tissue sections were incubated for 45 minutes at 22°C (room temperature) with an avidin–biotin horseradish peroxidase system (Vectastain ABC Elite; Vector Laboratories) followed by detection with diaminobenzidine, counterstaining with 2% methyl green and mounting. A positive tissue control and a negative reagent control (no primary antibody) were run in parallel. The level of expression was assessed by light microscopic visualization and scored as described previously by estimating the signal intensity (0–3) and the percentage of the tissue section staining positive (0–100%).

Results

The clinical-pathology characteristics of the study cohort

The overall pathology of the cases that led to an excision biopsy is listed in Table 1. The 62 cases included 24 cases diagnosed with benign non-proliferative disease (NPD; including fibrocystic changes without ductal hyper-plasia), 24 cases with proliferative disease without atypia (PDWA), and 14 cases with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). In all cases the tissue blocks selected for this study were from the resection margins and were reviewed to ensure that none represented the primary lesion (such as DCIS or florid epithelial hyperplasia lesions) that had been the principal focus of the biopsy. Patient ages ranged from 54 to 75 years with an overall mean of 62 years, and means of 64, 62 and 61 years for each of the above three categories of pathology, respectively.

The relation between mammographic density and tissue pathology

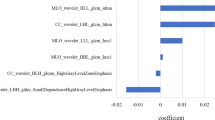

The distribution of cases in overall mammographic density categories is shown in Table 1 and was as follows: 0%, none; 0–10%, 17 cases (27%); 10–25%, 18 cases (29%); 50–75%, 22 cases (35%); 75–100%, 5 cases (8%). Cases associated with high mammographic density (50–100%) distant from the region of the primary lesion were associated with a significant increase in the proportion of cases diagnosed as DCIS relative to PDWA and NPD (P = 0.01, χ2 test). High mammographic density was also associated with differences in the tissue composition within the tissue blocks examined (Table 2). These cases exhibited more extensive fibrosis, measured either by the proportion of collagenous tissue within the tissue sections, the density of the collagenous tissue, or the extent of peri-ductal fibrosis. However, there was no difference in the density of epithelial components as measured by the number of duct or lobular units per mm2 between cases with high and low mammographic density (Fig. 1). Patients ranged in age from 54 to 74 years (mean 64) and 54 to 75 years (mean 60) in the categories of low and high mammographic density, respectively.

Relation between mammographic density and stromal proteoglycan expression

Lumican and decorin were assessed by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 2). As observed previously, the expression of both lumican and decorin was restricted to areas of collagenous stroma surrounding epithelial units. The expression of both SLRPs was significantly higher in cases with high mammographic density (Table 2), and was also correlated with the density of duct and lobular elements (lumican, r = 0.53, P < 0.0001; decorin, r = 0.49, P < 0.0001). The expression of lumican was also closely correlated with that of decorin (r = 0.93, P < 0.0001).

Representative tissue sections from breast tissue associated with low (left panels) and high (right panels) mammographic density. Increased collagenous stroma (upper right) and expression of lumican (middle right) and decorin (lower right) is present in breast tissue associated with high mammographic density. H&E sections (upper panels), lumican immunohistochemistry (middle panels), decorin immunohistochemistry (lower panels).

Discussion

Mammographic density might be a risk factor for the development of breast cancer [5, 6]. An improved understanding of factors influencing changes in mammographic density would improve its value and practical application in risk assessment. Mammographic density has been shown to be influenced by age, menopausal status and dietary factors and also by inherited genetic factors [9, 10, 23–34]. However, the biological basis underlying variations in mammographic density is unknown [35].

Many studies to explore these factors have examined the relationship between mammographic density and breast tissue pathology [8–10, 31, 32, 36, 37]. Although several of these have also noted a close association with stromal changes [32, 36–38], the tendency to focus principally on the relationship between increased mammographic density and specific epithelial lesions persists [7, 10, 31, 39]. The notion that increased mammographic density is attributable to the presence of more 'glandular tissue' reflects this view [35]. However, although statistically significant, the strength of the correlation between mammographic density and proliferative lesions in most studies is relatively weak.

The major tissue fraction in breast is stroma, not epithelial tissue. An alternative explanation is therefore that changes in mammographic density primarily reflect stromal changes and that these changes influence breast cancer risk [32]. Alteration of the stromal architecture and composition of the extracellular matrix is a well-recognized component of both benign and malignant breast pathologies, from the fibrosis within low-risk benign non-proliferative lesions (often encompassed by the term 'fibrocystic changes') through typical and atypical proliferative ductal lesions, to the 'stromal reaction' associated with ductal in situ and invasive carcinoma. Although the 'host reaction' in the latter malignant lesions has been attributed to paracrine perturbations originating from the epithelial tumour cell, fibrosis and stromal changes also occur in the absence of epithelial proliferation and can precede it. Recent studies have shown that both stromal architecture and composition can exert an important influence on normal epithelial biology [11, 40], and somatic mutations can be identified in the stromal compartment of breast tumours independently of mutations in the neoplastic epithelium [13, 14]. These observations are in keeping with the concept that stromal alterations might not always be 'reactive' but might sometimes play an initial 'landscaping' role in breast carcinogenesis, as has been proposed for the colon [41, 42].

In the present study we have also found a significant association between increased mammographic density and high-risk DCIS lesions. However, despite agreement with several previous studies, some limitations to the broader interpretation of this study should be noted. The study cohort was biased towards patients undergoing biopsies after the identification of lesions by screening mammography, and the majority of women were also probably postmenopausal, reducing the proportion of cases in the category of high mammographic density [25]. The mammographic density was assessed by subjective categorization, although we used well-established criteria applied to mammograms performed within a standardized screening programme and restricted our study set to patients with clearly distinguishable extents of mammographic density (less than 25% or more than 50% of the mammogram occupied by dense tissue). The relationship between the region assessed for density and the tissue blocks examined was not precise. However, we restricted our assessments of mammographic density and corresponding tissue to the margins of region of tissue encompassed by the subsequent biopsy, ignoring the locations influenced by the detected lesion.

Although there was an association with the occurrence of DCIS, our study showed no significant correlation between mammographic density and epithelial proliferation or density of epithelial duct-lobular units within the corresponding region of breast tissue beyond the primary lesion. Instead, there was a close correlation between the extent of collagenous stroma measured with several indices and its composition measured by the expression of the stromal proteoglycans lumican and decorin.

Breast stroma includes a variety of extracellular matrix proteins, of which the fibrillar collagens are perhaps the most important in determining stromal architecture. These are secreted as triple-helical procollagen molecules that undergo extracellular processing and assembly into collagen fibrils followed by cross-linking and aggregation to form collagen fibres. Fibrillogenesis and fibril spacing are important aspects of stromal integrity and are affected by several structural proteins and by proteoglycans, including the SLRPs lumican and decorin [18, 20], which are highly abundant in the stroma [16, 43]. Decorin can also exert biological effects directly through its influence on growth factors and growth factor receptors [19, 21]. The levels of expression of these SLRPs are correlated when compared within non-neoplastic or within neoplastic tissues, and low levels of both SLRPs are associated with poor outcome in primary invasive tumours. This latter observation might reflect a differential host response to tumour epithelium [17], although SLRP expression can vary independently of epithelial proliferative changes, as shown here, and alteration in the lumican : decorin ratio from that in normal tissue adjacent to the invasive margin can occur in neoplastic stroma [16]. The principal factors determining SLRP expression in breast are not known, although the expression of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) has been implicated as a risk factor for breast cancer [44] and is also known to be associated with mammographic density in premenopausal women [45]. IGF-1 can also induce lumican, decorin and collagen synthesis in model systems [46–48], with most influence on cells from younger patients [48], and both lumican and IGF-1 are often induced in benign disease in other tissues [49]. These last observations are consistent with the hypothesis that increased mammographic density might reflect primary stromal alterations, including SLRP expression, that could influence early tumorigenesis.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that mammographic density relates more to stromal rather than epithelial composition. Further studies in animal models will be needed to determine whether altered stromal composition and SLRP gene expression can exert direct effects on mammographic density and breast tumorigenesis.

Abbreviations

- DCIS:

-

ductal carcinoma in situ

- IGF:

-

insulin-like growth factor

- NPD:

-

non-proliferative disease

- PDWA:

-

proliferative disease without atypia

- SLRP:

-

small leucine-rich proteoglycan.

References

Ernster VL, Barclay J: Increases in ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of the breast in relation to mammography: a dilemma. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1997, 22: 151-156.

King MC, Wieand S, Hale K, Lee M, Walsh T, Owens K, Tait J, Ford L, Dunn BK, Costantino J, Wickerham L, Wolmark N, Fisher B: Tamoxifen and breast cancer incidence among women with inherited mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2: National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP-P1) Breast Cancer Prevention Trial. JAMA. 2001, 286: 2251-2256. 10.1001/jama.286.18.2251.

Dupont WD, Page DL: Risk factors for breast cancer in women with proliferative breast disease. N Engl J Med. 1985, 312: 146-151.

Allred DC, Mohsin SK, Fuqua SA: Histological and biological evolution of human premalignant breast disease. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2001, 8: 47-61.

Boyd NF, Martin LJ, Stone J, Greenberg C, Minkin S, Yaffe MJ: Mammographic densities as a marker of human breast cancer risk and their use in chemoprevention. Curr Oncol Rep. 2001, 3: 314-321.

Heine JJ, Malhotra P: Mammographic tissue, breast cancer risk, serial image analysis, and digital mammography. Part 1. Tissue and related risk factors. Acad Radiol. 2002, 9: 298-316. 10.1016/S1076-6332(03)80373-2.

Lee NA, Rusinek H, Weinreb J, Chandra R, Toth H, Singer C, Newstead G: Fatty and fibroglandular tissue volumes in the breasts of women 20–83 years old: comparison of X-ray mammography and computer-assisted MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997, 168: 501-506.

Urbanski S, Jensen HM, Cooke G, McFarlane D, Shannon P, Kruikov V, Boyd NF: The association of histological and radiological indicators of breast cancer risk. Br J Cancer. 1988, 58: 474-479.

Boyd NF, Jensen HM, Cooke G, Han HL: Relationship between mammographic and histological risk factors for breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1992, 84: 1170-1179.

Boyd NF, Jensen HM, Cooke G, Han HL, Lockwood GA, Miller AB: Mammographic densities and the prevalence and incidence of histological types of benign breast disease. Reference Pathologists of the Canadian National Breast Screening Study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2000, 9: 15-24. 10.1097/00008469-200002000-00003.

Roskelley CD, Bissell MJ: Dynamic reciprocity revisited: a continuous, bidirectional flow of information between cells and the extracellular matrix regulates mammary epithelial cell function. Biochem Cell Biol. 1995, 73: 391-397.

Lelievre SA, Weaver VM, Nickerson JA, Larabell CA, Bhaumik A, Petersen OW, Bissell MJ: Tissue phenotype depends on reciprocal interactions between the extracellular matrix and the structural organization of the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998, 95: 14711-14716. 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14711.

Kurose K, Hoshaw-Woodard S, Adeyinka A, Lemeshow S, Watson PH, Eng C: Genetic model of multi-step breast carcinogenesis involving the epithelium and stroma: clues to tumour-microenvironment interactions. Hum Mol Genet. 2001, 10: 1907-1913. 10.1093/hmg/10.18.1907.

Kurose K, Gilley K, Matsumoto S, Watson PH, Zhou XP, Eng C: Frequent somatic mutations in PTEN and TP53 are mutually exclusive in the stroma of breast carcinomas. Nat Genet. 2002, 32: 355-357. 10.1038/ng1013.

Moinfar F, Man YG, Arnould L, Bratthauer GL, Ratschek M, Tavas-soli FA: Concurrent and independent genetic alterations in the stromal and epithelial cells of mammary carcinoma: implications for tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2000, 60: 2562-2566.

Leygue E, Snell L, Dotzlaw H, Troup S, Hiller-Hitchcock T, Murphy LC, Roughley PJ, Watson PH: Lumican and decorin are differentially expressed in human breast carcinoma. J Pathol. 2000, 192: 313-320. 10.1002/1096-9896(200011)192:3<313::AID-PATH694>3.3.CO;2-2.

Troup S, Njue C, Kliewer EV, Parisien M, Roskelley C, Chakravarti S, Roughley PJ, Murphy LC, Watson PH: Reduced expression of the small leucine-rich proteoglycans, lumican, and decorin is associated with poor outcome in node-negative invasive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003, 9: 207-214.

Chakravarti S, Magnuson T, Lass JH, Jepsen KJ, LaMantia C, Carroll H: Lumican regulates collagen fibril assembly: skin fragility and corneal opacity in the absence of lumican. J Cell Biol. 1998, 141: 1277-1286. 10.1083/jcb.141.5.1277.

Iozzo RV, Moscatello DK, McQuillan DJ, Eichstetter I: Decorin is a biological ligand for the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 1999, 274: 4489-4492. 10.1074/jbc.274.8.4489.

Danielson KG, Baribault H, Holmes DF, Graham H, Kadler KE, Iozzo RV: Targeted disruption of decorin leads to abnormal collagen fibril morphology and skin fragility. J Cell Biol. 1997, 136: 729-743. 10.1083/jcb.136.3.729.

Iozzo RV: The biology of the small leucine-rich proteoglycans. Functional network of interactive proteins. J Biol Chem. 1999, 274: 18843-18846. 10.1074/jbc.274.27.18843.

Boyd NF, Stone J, Martin LJ, Jong R, Fishell E, Yaffe M, Hammond G, Minkin S: The association of breast mitogens with mammographic densities. Br J Cancer. 2002, 87: 876-882. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600537.

Boyd NF, Dite GS, Stone J, Gunasekara A, English DR, McCredie MR, Giles GG, Tritchler D, Chiarelli A, Yaffe MJ, Hopper JL: Heritability of mammographic density, a risk factor for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002, 347: 886-894. 10.1056/NEJMoa013390.

Greendale GA, Reboussin BA, Slone S, Wasilauskas C, Pike MC, Ursin G: Postmenopausal hormone therapy and change in mammographic density. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003, 95: 30-37. 10.1093/jnci/95.1.30.

Boyd N, Martin L, Stone J, Little L, Minkin S, Yaffe M: A longitudinal study of the effects of menopause on mammographic features. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002, 11: 1048-1053.

van Gils CH, Hendriks JH, Holland R, Karssemeijer N, Otten JD, Straatman H, Verbeek AL: Changes in mammographic breast density and concomitant changes in breast cancer risk. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1999, 8: 509-515.

Byrne C, Schairer C, Wolfe J, Parekh N, Salane M, Brinton LA, Hoover R, Haile R: Mammographic features and breast cancer risk: effects with time, age, and menopause status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995, 87: 1622-1629.

Haiman CA, Hankinson SE, De Vivo I, Guillemette C, Ishibe N, Hunter DJ, Byrne C: Polymorphisms in steroid hormone pathway genes and mammographic density. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003, 77: 27-36. 10.1023/A:1021112121782.

Heine JJ, Malhotra P: Mammographic tissue, breast cancer risk, serial image analysis, and digital mammography. Part 2. Serial breast tissue change and related temporal influences. Acad Radiol. 2002, 9: 317-335. 10.1016/S1076-6332(03)80374-4.

Brisson J, Brisson B, Cote G, Maunsell E, Berube S, Robert J: Tamoxifen and mammographic breast densities. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000, 9: 911-915.

Friedenreich CM, Bryant HE, Alexander F, Hugh J, Danyluk J, Page DL: Risk factors for benign breast biopsies: a nested case-control study in the Alberta breast screening program. Cancer Detect Prev. 2001, 25: 280-291.

Guo YP, Martin LJ, Hanna W, Banerjee D, Miller N, Fishell E, Khokha R, Boyd NF: Growth factors and stromal matrix proteins associated with mammographic densities. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001, 10: 243-248.

Vachon CM, Sellers TA, Vierkant RA, Wu FF, Brandt KR: Case-control study of increased mammographic breast density response to hormone replacement therapy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002, 11: 1382-1388.

Haiman CA, Bernstein L, Berg D, Ingles SA, Salane M, Ursin G: Genetic determinants of mammographic density. Breast Cancer Res. 2002, 4: R5-10.1186/bcr434.

Thurfjell E: Breast density and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002, 347: 866-10.1056/NEJMp020093.

Arthur JE, Ellis IO, Flowers C, Roebuck E, Elston CW, Blamey RW: The relationship of 'high risk' mammographic patterns to histological risk factors for development of cancer in the human breast. Br J Radiol. 1990, 63: 845-849.

Bright RA, Morrison AS, Brisson J, Burstein NA, Sadowsky NS, Kopans DB, Meyer JE: Relationship between mammographic and histologic features of breast tissue in women with benign biopsies. Cancer. 1988, 61: 266-271.

Bartow SA, Pathak DR, Mettler FA, Key CR, Pike MC: Breast mammographic pattern: a concatenation of confounding and breast cancer risk factors. Am J Epidemiol. 1995, 142: 813-819.

Byrne C, Schairer C, Brinton LA, Wolfe J, Parekh N, Salane M, Carter C, Hoover R: Effects of mammographic density and benign breast disease on breast cancer risk (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 2001, 12: 103-110. 10.1023/A:1008935821885.

Lochter A, Bissell MJ: Involvement of extracellular matrix constituents in breast cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 1995, 6: 165-173. 10.1006/scbi.1995.0017.

Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B: Landscaping the cancer terrain. Science. 1998, 280: 1036-7. 10.1126/science.280.5366.1036.

Yoo LI, Chung DC, Yuan J: LKB1 – a master tumour suppressor of the small intestine and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002, 2: 529-535. 10.1038/nrc843.

Leygue E, Snell L, Dotzlaw H, Hole K, Hiller-Hitchcock T, Roughley PJ, Watson PH, Murphy LC: Expression of lumican in human breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1998, 58: 1348-1352.

Pollak M: Insulin-like growth factor physiology and cancer risk. Eur J Cancer. 2000, 36: 1224-1228. 10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00102-7.

Byrne C, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Speizer FE, Pollak M, Hankinson SE: Plasma insulin-like growth factor (IGF) I, IGF-binding protein 3, and mammographic density. Cancer Res. 2000, 60: 3744-3748.

Haase HR, Clarkson RW, Waters MJ, Bartold PM: Growth factor modulation of mitogenic responses and proteoglycan synthesis by human periodontal fibroblasts. J Cell Physiol. 1998, 174: 353-361. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199803)174:3<353::AID-JCP9>3.3.CO;2-D.

Melching LI, Roughley PJ: Modulation of keratan sulfate synthesis on lumican by the action of cytokines on human articular chondrocytes. Matrix Biol. 1999, 18: 381-390. 10.1016/S0945-053X(99)00033-5.

d'Avis PY, Frazier CR, Shapiro JR, Fedarko NS: Age-related changes in effects of insulin-like growth factor I on human osteoblast-like cells. Biochem J. 1997, 324 (Pt 3): 753-760.

Luo J, Dunn T, Ewing C, Sauvageot J, Chen Y, Trent J, Isaacs W: Gene expression signature of benign prostatic hyperplasia revealed by cDNA microarray analysis. Prostate. 2002, 51: 189-200. 10.1002/pros.10087.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the assistance of Marion Harrison, Director of the Manitoba Provincial Breast Screening Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alowami, S., Troup, S., Al-Haddad, S. et al. Mammographic density is related to stroma and stromal proteoglycan expression. Breast Cancer Res 5, R129 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr622

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr622