Abstract

Introduction

Understanding whether mammographic density (MD) is associated with all breast tumor subtypes and whether the strength of association varies by age is important for utilizing MD in risk models.

Methods

Data were pooled from six studies including 3414 women with breast cancer and 7199 without who underwent screening mammography. Percent MD was assessed from digitized film-screen mammograms using a computer-assisted threshold technique. We used polytomous logistic regression to calculate breast cancer odds according to tumor type, histopathological characteristics, and receptor (estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER2)) status by age (<55, 55–64, and ≥65 years).

Results

MD was positively associated with risk of invasive tumors across all ages, with a two-fold increased risk for high (>51%) versus average density (11-25%). Women ages <55 years with high MD had stronger increased risk of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) compared to women ages 55–64 and ≥65 years (Page-interaction = 0.02). Among all ages, MD had a stronger association with large (>2.1 cm) versus small tumors and positive versus negative lymph node status (P’s < 0.01). For women ages <55 years, there was a stronger association of MD with ER-negative breast cancer than ER-positive tumors compared to women ages 55–64 and ≥65 years (Page-interaction = 0.04). MD was positively associated with both HER2-negative and HER2-positive tumors within each age group.

Conclusion

MD is strongly associated with all breast cancer subtypes, but particularly tumors of large size and positive lymph nodes across all ages, and ER-negative status among women ages <55 years, suggesting high MD may play an important role in tumor aggressiveness, especially in younger women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mammographic density (MD) is one of the strongest risk factors for breast cancer: women in the highest quartile of MD have four to six times increased risk of breast cancer compared with those in the lowest quartile [1]. The magnitude of risk associated with established breast cancer risk factors, such as age, menopausal status, and parity, differs according to tumor characteristics [2–6], suggesting breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease that develops through different pathways and may have etiologically distinct tumor subtypes. Because MD is a potential risk factor for prediction models, understanding whether MD is a risk factor for all breast cancer subtypes, including the most aggressive, and whether these associations are consistent at all ages is highly significant.

To date, the MD and breast cancer association according to different tumor characteristics is inconsistent [7–20]. Some previous analyses report no clear differences in strength of association by tumor characteristics [10–12, 16–20], while others suggest the association between MD and breast cancer risk differs by estrogen receptor (ER) status [13–16], invasiveness [15, 21], and tumor size [7–9]. Most [7–9, 15, 22], but not all [10], prior studies have reported stronger associations of MD with large tumors versus small tumors, which could reflect delays in diagnosis due to reduced sensitivity of mammography [23] and/or aggressive tumor biology.

Given these conflicting results and known differences in the tumor biology of younger and older women diagnosed with breast cancer [24–26], we conducted a large, comprehensive pooled analysis of six case–control studies, two of which were nested within cohorts, to examine risk of breast cancer associated with MD by age and tumor characteristics.

Methods

Study populations

Participating studies included the Mayo Mammography Health Study (MMHS) [27, 28], the Mayo Clinic Breast Cancer Study (MCBCS) [29, 30], the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and NHSII [31–33], the Mayo Clinic Mammography Study (MCMAM) [34], and the San Francisco Bay Area Breast Cancer SPORE and San Francisco Mammography Registry (SFMR) [35–37] (Table 1; see also Additional file 1). From all studies, we excluded breast cancer cases diagnosed within 6 months of mammography and their matched controls, to minimize prevalent cancers at the time of mammography. Covariate information was obtained from medical record review (MCMAM), self-administered questionnaires (NHS, NHSII), or both (MMHS, MCBCS), prior to mammography (NHS and NHSII) or at the time of mammography (MCBCS, MMHS, MCMAM, and SFMR). In total, these analyses included 3,414 breast cancer cases and 7,199 controls.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the Mayo Clinic, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), and the Connecticut Department of Public Health Human Investigations Committee. Informed consent was obtained or implied by return of questionnaires (NHS, NHSII).

Assessment of mammographic density

MD was measured using two computer-assisted threshold techniques (Cumulus [38] and UCSF custom mammographic density software [39]) from digitized images of prediagnostic film screening mammograms of the craniocaudal view. With the exception of NHS and NHSII, for which the average percent MD of both breasts was used, MD was estimated from the contralateral breast for cases and the corresponding side for matched controls. Previous studies have documented that similar results are obtained from an average of both breasts and from a randomly selected side [40] and the correlation between the right and left breast MD is 0.96 [41].

Because of known differences in the distribution of percent MD between readers [42, 43], we standardized MD measurements made within each study (Additional file 1) for pooled analyses. Briefly, we focused on women without breast cancer and estimated study-specific linear age trends in the medians of the logit-transformed MD values using quantile regression. We removed the study-specific age trends by computing the difference between each individual’s observed logit-transformed MD and the age-predicted median logit-transformed MD from the corresponding study set. We standardized the variability across studies by dividing the residuals within each study by their corresponding interquartile range, and multiplied these rescaled residual values by the interquartile range of the original residuals from all studies. This ensured that the variability in standardized logit-transformed MD was consistent across studies, and was roughly equivalent to the observed variability in logit-transformed MD. Finally, we estimated an overall age by logit-transformed MD trend from the original data, and added the age-predicted median logit-transformed MD to the rescaled residuals from each individual. This incorporated the known age trend in MD into the standardized logit-transformed MD measurements. These logit-transformed MD values were back-transformed to the original scale for use in analyses.

Assessment of tumor characteristics among cases

Information on tumor type, histology, grade, nodal involvement, tumor size, and ER, progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) status was obtained from state-wide Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results programs (SFMR), pathology reports (NHS and NHSII), state and clinic cancer registries (MMHS, MCMAM, MCBCS), and medical records (MMHS, MCMAM, MCBCS). For 66 cases in NHS or NHSII with missing receptor data on pathology reports, receptor status was obtained from immunohistochemical staining performed on paraffin sections of the tumor tissue microarray according to a standard protocol [44]. A large proportion of cases (39%) were missing HER2 status; and 31% of cases were diagnosed prior to the availability of herceptin and the need for HER2 testing, primarily from the MCMAM and NHS studies that were mostly postmenopausal cases. Another 2% were cases with borderline HER2 results (2+ without available fluorescent in situ hybridization) and were not used in analyses.

Statistical analyses

Standardized percent MD was categorized as 0 to 10%, 11 to 25%, 26 to 50%, and 51%+, with the average MD group (11 to 25%) as the reference group consistent with previous analyses [17, 37]. We fit polytomous (multinomial) logistic regression models to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals for the associations of MD with overall breast cancer as well as with breast cancer defined by tumor type (invasive or ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)), histologic type (ductal or lobular), grade (well differentiated, moderately differentiated, or poorly differentiated), tumor size (<1.1 cm, 1.1 to 2.0 cm, or 2.1+ cm), involvement of lymph nodes (positive or negative), and receptor status (ER-positive or ER-negative, PR-positive or PR-negative, HER2-positive or HER2-negative).

We pooled data across the six studies and adjusted for study, age (continuous), and body mass index (continuous) in multivariable models. We further considered potential confounding by parity (nulliparous, parous, or unknown) and first-degree family history of breast cancer (yes, no, or unknown) by evaluating the magnitude of change in ORs observed after including each potential confounder individually in the model. Postmenopausal hormone therapy (current estrogen alone, current estrogen plus progesterone, never/former, or unknown) was also evaluated as a confounder among postmenopausal women in the subset of studies for which this information was available (MMHS, NHS, NHSII, and SFMR). Addition of these variables to the models did not substantially change risk estimates and they were not included in final models. Results were similar in sensitivity analyses restricted to Caucasians only (data not shown).

Because prior studies suggest differences in the strength of the association of MD with breast cancer by age [45], and since tumor biology varies with age [24–26], analyses were conducted across all women and stratified by three age groups (<55 years, 55 to 64 years, and ≥65 years) to best capture these differences. We evaluated whether the associations between MD and breast cancer differed by specific tumor characteristics, both overall and within age group, using polytomous logistic regression models (Pheterogeneity). For subtypes with a natural ordering, including tumor size and grade, tests of trend (Ptrend) across categories were used to assess significance. Formal tests of interaction (Page-interaction) assessed the significance of differential MD associations with each of the breast cancer characteristics and subtypes across the three age groups.

Prior to pooling data across the six studies, study-specific estimates were obtained by fitting separate models for each study and assessing individual associations between MD and each tumor subtype. We assessed the statistical significance of differences in associations by study through testing for interactions between study group and MD category in the pooled analysis, and found no evidence of differences across study (all P values >0.29).

Analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). All statistical tests were two-sided and P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Overall, the mean age at mammogram was 57 years among both cases and controls. The mean time to diagnosis was 4.5 years (range: 0.5 to 17.6). Among both cases and controls, the mean percent MD decreased with age, but in each age group the mean percent MD was higher among cases versus controls (Table 2). DCIS was more common among younger women compared with older women, while invasive breast cancers in women <55 years at mammography generally displayed more aggressive tumor characteristics compared with women ≥55 years (Table 3).

Overall and invasive breast cancer and ductal carcinoma in situ

A positive association of MD with breast cancer overall, adjusted for age and body mass index, was seen for each study (Table S1 in Additional file 2). In the pooled analysis, MD was positively associated with breast cancer risk overall and with invasive cancer, after adjusting for study, body mass index, and age, with similar magnitudes of effect in each MD category (Table 4). However, the difference in the magnitude of association of MD with breast cancer by tumor type (invasive vs. DCIS) varied significantly across age groups (Page-interaction = 0.02; Table S2 in Additional file 2). There were similar associations of MD with invasive breast cancer across age groups (Figure 1; see also Table S2 in Additional file 2). But the associations of MD with DCIS differed, primarily for women aged <55 years compared with those aged ≥55 years. Younger women with high MD had increased risk of DCIS (ORs for MD 26 to 50% and 51% + vs. MD 11 to 25% were 1.99 and 2.39, respectively) that was not as strong in older age groups (corresponding ORs of 1.59 and 1.47 for age 55 to 64, and 1.22 and 0.96 for age ≥65 years) (Figure 1; see also Table S2 in Additional file 2).

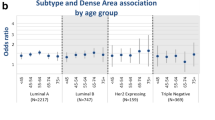

Pooled associations of categorical mammographic density for tumor type and morphological subtypes of invasive breast cancer by age. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals adjusted for age, body mass index, and study are shown for each category of mammographic density (MD): 1, 0 to 10% MD; 2, 11 to 25% MD (reference); 3, 26 to 50% MD; 4, 51% + MD). (A) Tumor type. (B) Histology. (C) Tumor grade. (D) Tumor size. (E) Lymph node involvement. (F) Estrogen receptor (ER) status. (G) Progesterone receptor (PR) status. (H) Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) status. DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ.

Grade, invasive histology, size and nodal status

MD was similarly associated with breast cancers of various grades (Table 4). Further, this association did not differ when stratified by age group (Page-interaction =0.21) (Figure 1; see also Table S3 in Additional file 2). MD was also similarly associated with both ductal and lobular histology among all ages combined (Table 4). Despite evidence of heterogeneity in the association by histologic subtype overall (Pheterogeneity = 0.04), the magnitude of the association was similar within each age group (all Pheterogeneity ≥0.12) and there was no evidence of significant interaction by age (Page-interaction = 0.15). Also, higher MD was positively associated with invasive tumors of all sizes but the association was stronger for large tumors (that is, 2.1+ cm) compared with small tumors <1.1 cm among all women combined (Ptrend <0.01; Table 4) and within age groups (Figure 1; see also Table S3 in Additional file 2). The ORs for MD 51% + versus MD 11 to 25% ranged from 1.33 to 1.61 for invasive tumors <1.1 cm and from 2.88 to 3.65 for tumors 2.1+ cm. Low MD (that is, 0 to 10%) was not significantly associated with a reduced risk of tumors <1.1 cm compared with the referent category MD 11 to 25%; however, for tumors >1.1 cm, low MD was significantly associated with lower risk (ORs: 0.31 to 0.60) (Figure 1; see also Table S3 in Additional file 2). MD was associated with both lymph node-positive and lymph node-negative tumors among all ages combined, with a stronger association of MD with node-positive than node-negative tumors (Pheterogeneity <0.01) (Table 4). The MD association with breast cancer defined by nodal status was not different by age group (Page-interaction = 0.24), although there was evidence of a stronger association for node-positive versus node-negative tumors among women ages ≥65 (Pheterogeneity = 0.04).

Estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor and HER2 status

Associations between MD and breast cancer defined by ER status differed by age group (Page-interaction = 0.04). For women aged <55 years, a stronger association was observed for ER-negative disease (OR: 2.84, 95% confidence interval: 1.83, 4.40) versus ER-positive disease (OR: 1.96; 95% confidence interval: 1.56, 2.45) for MD 51% + versus MD 11 to 25% (Pheterogeneity = 0.09), while associations for women aged ≥55 years were nonstatistically significantly stronger for ER-positive tumors versus ER-negative tumors. MD was similarly associated with PR-negative and PR-positive tumors in all age groups (Page-interaction = 0.10). While there was evidence of a significant interaction between MD and breast cancers by HER2 status and age group (Page-interaction = 0.03), MD was positively associated with both HER2-negative and HER-positive disease in all age groups and there were no clear patterns of differences in associations (Figure 1; see also Table S3 in Additional file 2).

Discussion

In this large pooled analysis we confirmed a positive association between MD and breast cancer risk. Women with high MD (51%+) had an approximately two-fold higher risk of breast cancer compared with women with MD 11 to 25%, and those with less extensive mammographic density (0 to 10%) had almost one-half the risk as those with 11 to 25% MD. This translates to a relative risk of around four comparing the highest category of MD with the lowest, similar to prior studies. Our findings suggest that MD is a risk factor for all histologic/morphologic subtypes of breast cancer examined, but a stronger risk factor for tumors of large (vs. small) size and node-positive (vs. node-negative) disease among all women. We found differential associations of MD and breast cancer defined by tumor type (DCIS vs. invasive cancer), ER status and HER2 status, by age group (<55 years, 55 to 64 years and ≥65 years).

Most previous studies of the association between MD and breast cancer tumor characteristics have focused on hormone receptor status, with somewhat conflicting results [9–11, 13–17, 20, 37, 46, 47] – in part because most studies have not examined associations by age group and/or menopausal status. Several studies, including a recent meta-analysis [19], reported no difference in associations between MD and breast cancer by ER status [9, 10, 19, 20, 37, 46, 47], while others reported stronger associations for ER-positive disease [13, 14, 18]. In contrast, a significantly stronger effect of MD on postmenopausal breast cancer was reported for ER-negative compared with ER-positive tumors among the NHS cohort, but the number of ER-negative cases was small [15]. Findings from the current pooled analysis stratified by age group, which included women in the NHS [15], suggest that MD is more strongly associated with ER-negative breast cancer (vs. ER-positive) among women <55 years old compared with women aged 55 years and older. Like other studies [37], we found no difference in associations by PR status; however, one recent case-only study found that tumors diagnosed in women with denser breasts were more likely to be PR-positive compared with tumors in women with more fatty breasts [18]. Our findings of MD positively associated with both HER2-negative and HER2-positive tumors within age groups are consistent with prior studies [11, 15, 19, 20], including a meta-analysis of studies that did not show MD differentially associated by tumors defined by HER2 across all ages combined [19]. The significant interaction between MD, HER2 status, and age that we observed may have been influenced by small numbers of HER2-positive tumors in older age groups and/or due to chance. In addition, HER2 status was unknown for a moderate portion of cases, with the primary reason being a diagnosis date prior to when HER2 was clinically tested. Since the two older studies were comprised of postmenopausal cases, it is not surprising that we found those without HER2 more likely to be older and slightly more likely to be node-negative (80% of cases with unknown/borderline HER2 status were node-negative vs. 70% of those with known HER2 status). Otherwise, the majority of tumor characteristics were similar between the two groups. The results with HER2 will need to be confirmed in other studies.

Among women aged <55 years who had high MD, we noted similar associations for DCIS and invasive breast cancers. However, we noted a stronger association between MD and breast cancer for invasive versus DCIS cancers among women aged 55 to 64 years and ≥65 years. Three prior studies showed either similar associations of MD with DCIS [20, 48] and invasive breast cancer or somewhat stronger association for invasive tumors [21], while Yaghjyan and colleagues reported a significantly stronger association for in situ versus invasive tumors among postmenopausal women in the NHS [15]. The current study had a greater number of DCIS cases (555 vs. ≤300) and stratified associations by three age groups. In fact, when we examined the association of MD and tumor type overall, we found no difference in the association by DCIS versus invasive cancer, underscoring the importance of examining age-specific associations.

Our findings of stronger associations between MD and large compared with small tumors within each age group are consistent with most prior studies [7–9, 15, 22]. In addition, we noted a stronger association between MD and tumors with lymph node involvement compared with node-negative tumors. Both of these associations are consistent with studies that have reported positive associations with MD and breast cancers with aggressive tumor characteristics, including positive lymph nodes and advanced stage [7–9, 49]. However, we found no evidence of differential associations by tumor grade. Observations of stronger associations between MD and more advanced tumors (for example, large size, node-positive) could perhaps reflect a possible masking effect because of reduced mammographic sensitivity and consequent delay in diagnosis [20, 22, 23]. The mean time between mammography and diagnosis was 4.6 years, and many of these women were screened annually, reducing the possible influence of a masking effect. While we observed a slightly stronger association between MD and lobular (vs. ductal) breast tumors among all women, this was not as apparent in age-stratified analyses and is in contrast to previous studies, which reported similar associations by histology [10, 12, 18].

Taken together, our findings suggest that MD is a risk factor for all types of breast cancer. However, some differences in magnitudes of risk associated with MD were noted for specific tumor characteristics primarily related to detection (for example, tumor size and nodal involvement in women of all ages) and for tumor characteristics primarily related to tumor biology (tumor type in older women and ER status in younger women). These observations point to possible heterogeneity by tumor characteristics and, if confirmed and corroborated by molecular-based studies, provide insight into the biological mechanisms by which MD differentially influences cancer risk.

Some limitations to this study are worth noting. We pooled data from six different studies, which varied in study design, population characteristics, geography, and calendar year. Our study used clinical pathology information and not centralized pathology review. In addition, there may have been changes in diagnostic criteria over time (for example, differences in threshold for positivity for ER status or HER2 testing). For example, some of the earliest diagnoses from the NHS included in this analysis were from the early 1990s before fluorescent in situ hybridization testing was routine. However, we found no evidence of between-study heterogeneity in our results. Further, any differences would be expected to attenuate associations with MD. The majority of women in our study were Caucasian; therefore, our findings may not be generalizable to non-Caucasians. Finally, we lacked data on the detection method (for example, screening-detected vs. interval-detected cancer), which could have helped to clarify the extent to which our observations reflect delays in diagnosis or tumor biology.

Strengths of the study included the sample of over 3,400 breast cancer cases, providing sufficient statistical power to examine associations by age group; cases and controls (except MCBCS) selected from underlying prospective cohort studies or registries with a mean time between mammogram and breast cancer diagnosis of 4.6 years; and comparable estimates of percent MD across readers at the three study sites with demonstrated high intra-reader reliability (intraclass correlation = 0.91 to 0.97) and standardization of percent MD for pooled analyses. The lack of between-study heterogeneity further suggests that pooling these data is appropriate. Also, we had detailed information on tumor characteristics from pathology reports supplemented with information from tissue microarrays. Finally, all mammograms were screening in nature.

Conclusion

We observed significant positive associations between MD and breast cancer risk across tumor characteristics and age groups. In addition, we noted stronger associations for tumors of large size and positive lymph nodes across all ages, and ER-negative status among women aged <55 years, suggesting that high MD may play an important role in tumor aggressiveness, especially in younger women. Understanding similarities and differences in etiologic pathways according to breast cancer tumor characteristics and age has important implications for development of risk models and tailored primary prevention. Incorporating MD and traditional breast cancer risk factors into risk prediction models overall and into models unique to subtype may improve their predictive ability and allow clinicians to identify women at increased risk of breast cancer for targeted prevention efforts. Moreover, because MD itself is a potentially modifiable risk factor [50], understanding how it is differentially associated with breast cancer subtypes by age, particularly subtypes with poor prognosis more commonly diagnosed in younger women, could lead to novel strategies to reduce breast cancer incidence.

Abbreviations

- DCIS:

-

Ductal carcinoma in situ

- ER:

-

Estrogen receptor

- HER2:

-

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- MCBCS:

-

Mayo Clinic Breast Cancer Study

- MCMAM:

-

Mayo Clinic Mammography Study

- MD:

-

Mammographic density

- MMHS:

-

Mayo Mammography Health Study

- NHS:

-

Nurses’ Health Study

- OR:

-

Odds ratios

- PR:

-

Progesterone receptor

- SFMR:

-

San Francisco Bay Area Breast Cancer SPORE and San Francisco Mammography Registry

- UCSF:

-

University of California, San Francisco.

References

McCormack VA, dos Santos SI: Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006, 15: 1159-1169.

Colditz GA, Rosner BA, Chen WY, Holmes MD, Hankinson SE: Risk factors for breast cancer according to estrogen and progesterone receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004, 96: 218-228.

Rusiecki JA, Holford TR, Zahm SH, Zheng T: Breast cancer risk factors according to joint estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor status. Cancer Detect Prev. 2005, 29: 419-426.

Yasui Y, Potter JD: The shape of age-incidence curves of female breast cancer by hormone-receptor status. Cancer Causes Control. 1999, 10: 431-437.

Yang XR, Chang-Claude J, Goode EL, Couch FJ, Nevanlinna H, Milne RL, Gaudet M, Schmidt MK, Broeks A, Cox A, Fasching PA, Hein R, Spurdle AB, Blows F, Driver K, Flesch-Janys D, Heinz J, Sinn P, Vrieling A, Heikkinen T, Aittomäki K, Heikkilä P, Blomqvist C, Lissowska J, Peplonska B, Chanock S, Figueroa J, Brinton L, Hall P, Czene K, et al: Associations of breast cancer risk factors with tumor subtypes: a pooled analysis from the breast cancer association consortium studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011, 103: 250-263.

Turkoz FP, Solak M, Petekkaya I, Keskin O, Kertmen N, Sarici F, Arik Z, Babacan T, Ozisik Y, Altundag K: Association between common risk factors and molecular subtypes in breast cancer patients. Breast. 2012, 22: 344-350.

Sala E, Solomon L, Warren R, McCann J, Duffy S, Luben R, Day N: Size, node status and grade of breast tumours: association with mammographic parenchymal patterns. Eur Radiol. 2000, 10: 157-161.

Roubidoux MA, Bailey JE, Wray LA, Helvie MA: Invasive cancers detected after breast cancer screening yielded a negative result: relationship of mammographic density to tumor prognostic factors. Radiology. 2004, 230: 42-48.

Aiello EJ, Buist DS, White E, Porter PL: Association between mammographic breast density and breast cancer tumor characteristics. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005, 14: 662-668.

Ghosh K, Brandt KR, Sellers TA, Reynolds C, Scott CG, Maloney SD, Carston MJ, Pankratz VS, Vachon CM: Association of mammographic density with the pathology of subsequent breast cancer among postmenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008, 17: 872-879.

Ma H, Luo J, Press MF, Wang Y, Bernstein L, Ursin G: Is there a difference in the association between percent mammographic density and subtypes of breast cancer? Luminal A and triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009, 18: 479-485.

Phipps AI, Li CI, Kerlikowske K, Barlow WE, Buist DS: Risk factors for ductal, lobular, and mixed ductal-lobular breast cancer in a screening population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010, 19: 1643-1654.

Ding J, Warren R, Girling A, Thompson D, Easton D: Mammographic density, estrogen receptor status and other breast cancer tumor characteristics. Breast J. 2010, 16: 279-289.

Conroy SM, Pagano I, Kolonel LN, Maskarinec G: Mammographic density and hormone receptor expression in breast cancer: the Multiethnic Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2011, 35: 448-452.

Yaghjyan L, Colditz GA, Collins LC, Schnitt SJ, Rosner B, Vachon C, Tamimi RM: Mammographic breast density and subsequent risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women according to tumor characteristics. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011, 103: 1179-1189.

Heusinger K, Jud SM, Haberle L, Hack CC, Adamietz BR, Meier-Meitinger M, Lux MP, Wittenberg T, Wagner F, Loehberg CR, Uder M, Hartmann A, Schulz-Wendtland R, Beckmann MW, Fasching PA: Association of mammographic density with hormone receptors in invasive breast cancers: results from a case-only study. Int J Cancer. 2012, 131: 2643-2649.

Phipps AI, Buist DS, Malone KE, Barlow WE, Porter PL, Kerlikowske K, O’Meara ES, Li CI: Breast density, body mass index, and risk of tumor marker-defined subtypes of breast cancer. Ann Epidemiol. 2012, 22: 340-348.

Eriksson L, Hall P, Czene K, Dos Santos SI, McCormack V, Bergh J, Bjohle J, Ploner A: Mammographic density and molecular subtypes of breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012, 107: 18-23.

Antoni S, Sasco AJ, Dos Santos SI, McCormack V: Is mammographic density differentially associated with breast cancer according to receptor status? A meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013, 137: 337-347.

Pollan M, Ascunce N, Ederra M, Murillo A, Erdozain N, Ales-Martinez JE, Pastor-Barriuso R: Mammographic density and risk of breast cancer according to tumor characteristics and mode of detection: a Spanish population-based case–control study. Breast Cancer Res. 2013, 15: R9-

Gill JK, Maskarinec G, Pagano I, Kolonel LN: The association of mammographic density with ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: the Multiethnic Cohort. Breast Cancer Res. 2006, 8: R30-

Porter GJ, Evans AJ, Cornford EJ, Burrell HC, James JJ, Lee AH, Chakrabarti J: Influence of mammographic parenchymal pattern in screening-detected and interval invasive breast cancers on pathologic features, mammographic features, and patient survival. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007, 188: 676-683.

Boyd NF, Guo H, Martin LJ, Sun L, Stone J, Fishell E, Jong RA, Hislop G, Chiarelli A, Minkin S, Yaffe MJ: Mammographic density and the risk and detection of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007, 356: 227-236.

Anderson WF, Chen BE, Brinton LA, Devesa SS: Qualitative age interactions (or effect modification) suggest different cancer pathways for early-onset and late-onset breast cancers. Cancer Causes Control. 2007, 18: 1187-1198.

Pollan M: Epidemiology of breast cancer in young women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010, 123: 3-6.

Yankaskas BC: Epidemiology of breast cancer in young women. Breast Dis. 2005, 23: 3-8.

Heine JJ, Scott CG, Sellers TA, Brandt KR, Serie DJ, Wu FF, Morton MJ, Schueler BA, Couch FJ, Olson JE, Pankratz VS, Vachon CM: A novel automated mammographic density measure and breast cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012, 104: 1028-1037.

Olson JE, Sellers TA, Scott CG, Schueler BA, Brandt KR, Serie DJ, Jensen MR, Wu FF, Morton MJ, Heine JJ, Couch FJ, Pankratz VS, Vachon CM: The influence of mammogram acquisition on the mammographic density and breast cancer association in the Mayo Mammography Health Study Cohort. Breast Cancer Res. 2012, 14: R147-

Kelemen LE, Couch FJ, Ahmed S, Dunning AM, Pharoah PD, Easton DF, Fredericksen ZS, Vierkant RA, Pankratz VS, Goode EL, Scott CG, Rider DN, Wang X, Cerhan JR, Vachon CM: Genetic variation in stromal proteins decorin and lumican with breast cancer: investigations in two case–control studies. Breast Cancer Res. 2008, 10: R98-

Wang X, Goode EL, Fredericksen ZS, Vierkant RA, Pankratz VS, Liu-Mares W, Rider DN, Vachon CM, Cerhan JR, Olson JE, Couch FJ: Association of genetic variation in genes implicated in the beta-catenin destruction complex with risk of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008, 17: 2101-2108.

Tamimi RM, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, Byrne C: Endogenous sex hormone levels and mammographic density among postmenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005, 14: 2641-2647.

Tworoger SS, Sluss P, Hankinson SE: Association between plasma prolactin concentrations and risk of breast cancer among predominately premenopausal women. Cancer Res. 2006, 66: 2476-2482.

Colditz GA, Hankinson SE: The Nurses’ Health Study: lifestyle and health among women. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005, 5: 388-396.

Vachon CM, Brandt KR, Ghosh K, Scott CG, Maloney SD, Carston MJ, Pankratz VS, Sellers TA: Mammographic breast density as a general marker of breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007, 16: 43-49.

Kerlikowske K, Carney PA, Geller B, Mandelson MT, Taplin SH, Malvin K, Ernster V, Urban N, Cutter G, Rosenberg R, Ballard-Barbash R: Performance of screening mammography among women with and without a first-degree relative with breast cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2000, 133: 855-863.

Kerlikowske K, Shepherd J, Creasman J, Tice JA, Ziv E, Cummings SR: Are breast density and bone mineral density independent risk factors for breast cancer?. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005, 97: 368-374.

Ziv E, Tice J, Smith-Bindman R, Shepherd J, Cummings S, Kerlikowske K: Mammographic density and estrogen receptor status of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004, 13: 2090-2095.

Byng JW, Boyd NF, Fishell E, Jong RA, Yaffe MJ: Automated analysis of mammographic densities. Phys Med Biol. 1996, 41 (5): 909-923.

Shepherd JA, Kerlikowske K, Ma L, Duewer F, Fan B, Wang J, Malkov S, Vittinghoff E, Cummings SR: Volume of mammographic density and risk of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011, 20: 1473-1482.

Byrne C, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Speizer FE, Pollak M, Hankinson SE: Plasma insulin-like growth factor (IGF) I, IGF-binding protein 3, and mammographic density. Cancer Res. 2000, 60: 3744-3748.

Benichou J, Byrne C, Capece LA, Carroll LE, Hurt-Mullen K, Pee DY, Salane M, Schairer C, Gail MH: Secular stability and reliability of measurements of the percentage of dense tissue on mammograms. Cancer Detect Prev. 2003, 27: 266-274.

Yaffe MJ: Mammographic density. Measurement of mammographic density. Breast Cancer Res. 2008, 10: 209-

Prevrhal S, Shepherd JA, Smith-Bindman R, Cummings SR, Kerlikowske K: Accuracy of mammographic breast density analysis: results of formal operator training. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002, 11: 1389-1393.

Tamimi RM, Baer HJ, Marotti J, Galan M, Galaburda L, Fu Y, Deitz AC, Connolly JL, Schnitt SJ, Colditz GA, Collins LC: Comparison of molecular phenotypes of ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2008, 10: R67-

Tice JA, Cummings SR, Smith-Bindman R, Ichikawa L, Barlow WE, Kerlikowske K: Using clinical factors and mammographic breast density to estimate breast cancer risk: development and validation of a new predictive model. Ann Intern Med. 2008, 148: 337-347.

Chen JH, Hsu FT, Shih HN, Hsu CC, Chang D, Nie K, Nalcioglu O, Su MY: Does breast density show difference in patients with estrogen receptor-positive and estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer measured on MRI?. Ann Oncol. 2009, 20: 1447-1449.

Yang WT, Dryden M, Broglio K, Gilcrease M, Dawood S, Dempsey PJ, Valero V, Hortobagyi G, Atchley D, Arun B: Mammographic features of triple receptor-negative primary breast cancers in young premenopausal women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008, 111: 405-410.

Reinier KS, Vacek PM, Geller BM: Risk factors for breast carcinoma in situ versus invasive breast cancer in a prospective study of pre- and post-menopausal women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007, 103: 343-348.

Kerlikowske K, Cook AJ, Buist DS, Cummings SR, Vachon C, Vacek P, Miglioretti DL: Breast cancer risk by breast density, menopause, and postmenopausal hormone therapy use. J Clin Oncol. 2010, 28: 3830-3837.

Cuzick J, Warwick J, Pinney E, Duffy SW, Cawthorn S, Howell A, Forbes JF, Warren RM: Tamoxifen-induced reduction in mammographic density and breast cancer risk reduction: a nested case–control study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011, 103: 744-752.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (R01 CA140286, R01 CA128931, P50 CA58207, P50 CA116201, R01 CA97396, R01 CA 122340, P01 CA087969, R01 CA050385, R01 CA124865, and R01 CA131332), the Breast Cancer Research Foundation and the Department of Defense (DAMD 17-00-1-033). KAB was supported by the Nutritional Epidemiology of Cancer Training Grant (R25 CA098566). The authors would like to thank the participants and staff of the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), NHSII and MMHS for their valuable contributions as well as the following state cancer registries for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, WY. Certain data used in this publication were obtained from the Connecticut Department of Public Health. The authors also thank Fang Fang Wu who provided percent MD estimates on all Mayo studies. The authors assume full responsibility for analyses and interpretation of these data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CMV, KK, and RMT conceived of and designed the study, directed statistical analyses, interpreted results, substantially revised initial drafts of the paper and provided final review and approval. JS led all aspects pertaining to mammogram acquisition and measurement of mammographic density for UCSF; he also provided substantial contribution to the interpretation of results and final approval of the manuscript. AN was the project manager of the overall study, providing study coordination and data acquisition for all combined information, harmonization of all data elements, as well as providing substantive comments to the drafts of the paper as well as final approval. BF acquired images and estimated mammographic density on UCSF mammograms, reviewed the initial and final drafts and provided final approval. Y-YC, DV, and AHB provided substantive pathology expertise to inform tumor characteristics and combination of information across studies, reviewed the drafts and provided comments and final approval. LM, CGS, MRJ, and VSP performed statistical analyses and interpretation of data, with input from KAB, RMT, KK and CMV. FC is the principal investigator of the MCBCS study and contributed substantive data, interpretation, drafting the manuscript and final approval. SRC is the principal investigator of one of the UCSF SFMR sites and contributed substantive data, interpretation, drafting the manuscript and final approval. KAB contributed to interpretation of analyses, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, which was critically revised by RMT, KK, and CMV, and approved the final draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Karla Kerlikowske and Celine M Vachon contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

13058_2013_3590_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Additional file 1: Additional methods, presenting detailed description of study populations and methods to standardize MD measurements.(PDF 147 KB)

13058_2013_3590_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Additional file 2: Table S1: Presenting associations of MD with breast cancer by study (OR (95% confidence interval)); Table S2. Presenting pooled associations of categorical MD with breast cancer overall and by tumor type and age; and Table S3. Presenting pooled associations of categorical percent MD for morphological subtypes of invasive breast cancer by age. (PDF 88 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Bertrand, K.A., Tamimi, R.M., Scott, C.G. et al. Mammographic density and risk of breast cancer by age and tumor characteristics. Breast Cancer Res 15, R104 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr3570

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr3570