Abstract

Introduction

Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease and may be characterized on the basis of whether estrogen receptors (ER) are expressed in the tumour cells. ER status of breast cancer is important clinically, and is used both as a prognostic indicator and treatment predictor. In this study, we focused on identifying genetic markers associated with ER-negative breast cancer risk.

Methods

We conducted a genome-wide association analysis of 285,984 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) genotyped in 617 ER-negative breast cancer cases and 4,583 controls. We also conducted a genome-wide pathway analysis on the discovery dataset using permutation-based tests on pre-defined pathways. The extent of shared polygenic variation between ER-negative and ER-positive breast cancers was assessed by relating risk scores, derived using ER-positive breast cancer samples, to disease state in independent, ER-negative breast cancer cases.

Results

Association with ER-negative breast cancer was not validated for any of the five most strongly associated SNPs followed up in independent studies (1,011 ER-negative breast cancer cases, 7,604 controls). However, an excess of small P-values for SNPs with known regulatory functions in cancer-related pathways was found (global P = 0.052). We found no evidence to suggest that ER-negative breast cancer shares a polygenic basis to disease with ER-positive breast cancer.

Conclusions

ER-negative breast cancer is a distinct breast cancer subtype that merits independent analyses. Given the clinical importance of this phenotype and the likelihood that genetic effect sizes are small, greater sample sizes and further studies are required to understand the etiology of ER-negative breast cancers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease and can be characterized on the basis of estrogen receptor (ER) expression in the tumour cells. The two breast cancer subtypes (ER-positive and ER-negative) are generally considered as biologically distinct diseases and have been associated with remarkably different gene expression profiles [1, 2]. ER status is important clinically, and is used both as a prognostic indicator and treatment predictor since it determines if a patient may benefit from anti-estrogen therapy. Approximately one-third of all breast cancers are ER-negative, and cancers of this ER subtype are highly age-dependent and generally have a more aggressive clinical course than hormone receptor-positive disease.

Estimates show that close to a third of the total risk of breast cancer may be attributed to heritable factors [3]. Several large-scale genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) association studies (GWAS) have identified multiple susceptibility loci for breast cancer [4–11], but it is estimated that the currently known common risk variants identified by this approach explains only 5.8% of the proportion of familial risk of breast cancer.

Aside from traditional agnostic SNP studies, pathway-based approaches have also emerged in the recent GWAS literature [12–20]. These novel methods have been developed to mine modest association signals from genome-wide SNP data using prior knowledge on biologically pathways and networks, and have the potential to complement traditional agnostic SNP approaches to provide fertile grounds for follow-up studies of both a genetic and molecular nature. Subtypes of breast cancer, to our knowledge, have not been studied using a pathway-based approach.

Although many of the SNPs identified for breast cancer through GWAS scans have been found to be more strongly associated with ER-positive disease than ER-negative disease [21, 22], there is no quantitative assessment on whether breast cancers of the two different ER subtypes share a polygenic component. In this study, we performed a genome-wide association scan on 617 ER-negative cases and 4,583 controls, the first of its kind, and examined 285,984 SNPs for common variants and biological pathways associated with this unique subtype of breast cancer. We also searched for evidence that ER-negative breast cancer is distinct from ER-positive breast cancer by assessing the amount of shared polygenic variation between the two breast cancer subtypes.

Materials and methods

Full methods accompany this paper in Additional file 1.

Study populations used in the discovery stage

Table 1 summarizes the demographics of cases and controls used in this study. The discovery stage consists of cases and controls from Finland and Sweden. The validation stage consists of breast cancer cases from two further studies: the Study of Epidemiology and Risk factors in Cancer Heredity (SEARCH) and Rotterdam Breast Cancer Study (RBCS) (1,011 ER-negative cases, 7,604 controls), both previously described in Lesueur et al. [23]. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. For all populations, blood samples were obtained from individuals according to protocols and informed-consent procedures approved by institutional review boards.

Briefly, the Swedish sample set included subjects who were drawn from a parent population-based case control study of postmenopausal breast cancer which has been described elsewhere [24, 25]. Case subjects were women born in Sweden who were 50 to 74 years of age at diagnosis and diagnosed with breast cancer between October 1993 and March 1995. A total of 803 individuals diagnosed with invasive breast cancer and with available blood samples were selected for GWAS genotyping in an independent GWAS looking at overall breast cancer risk [26]. Of these women, 153 individuals were diagnosed with the ER-negative disease and were included in the present study. In addition, a total of 1,414 Swedish controls were included from the parent study and an additional Epidemiological Investigation of Rheumatoid Arthritis (EIRA) study [27].

The Finnish breast cancer study population consists of two series of unselected breast cancer patients and additional familial cases ascertained at the Helsinki University Central Hospital. The first series of patients was collected in 1997 to 1998 and 2000 and covers 79% of all consecutive, newly diagnosed cases during the collection periods [28, 29]. The second series, containing newly diagnosed patients, was collected in 2001 to 2004 and covers 87% of all such patients treated at the hospital during the collection period [30]. The collection of additional familial cases has been described previously [31]. We genotyped a total of 782 breast cancer cases in an independent GWAS for overall breast cancer risk [26], of which 226 ER-negative cases were used in the present study. An additional 238 Finnish ER-negative cases were also genotyped for this study, using a different platform. Of these 464 women with ER-negative breast cancer, 207 were sporadic and 257 were familial breast cancer cases. Population control data were obtained from the Finnish Genome Centre on 3,169 healthy population controls described in [32–35].

SEARCH is a population-based case-control study comprising 7,093 cases identified through the East Anglian Cancer Registry: prevalent cases diagnosed age <55 from 1991 to 1996 and alive when the study started in 1996, and incident cases diagnosed <70 diagnosed after 1996. Controls (N = 8,096) were selected from the EPIC-Norfolk cohort study, a population-based cohort study of diet and health based in the same geographical region as SEARCH, together with additional SEARCH controls recruited through general practices in East Anglian region.

RBCS is a hospital-based case-control study comprising 799 cases characterized as familial breast cancer patients selected from the Rotterdam Family Cancer Clinic at the Erasmus Medical Center, of which 141 are ER-negative. Controls (N = 801) were spouses or mutation-negative siblings of heterozygous Cystic Fibrosis mutation carriers selected from the Department of Clinical Genetics at the Erasmus Medical Center. Both cases and controls were recruited between 1994 and 2006.

Genotyping and quality control filters

Genotyping for all samples was performed according to the Illumina Infinium 2 assay manual (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), as described previously [36]. The genotyping platforms used for this study are listed in Table 1. Apart from the 3,170 Finnish controls which were genotyped on the HumanHap370Duo assay as described previously [32, 34], genotyping for all other Finnish and Swedish samples was performed at the Genome Institute of Singapore.

Each dataset was filtered to remove individuals with >10% missing genotypes, and SNPs with >10% missing data, or minor allele frequency (MAF) <0.03, or not in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) (P < 0.05/number of SNPs after quality control) and individual samples with evidence of possible DNA contamination, common ancestry or cryptic family relationships. Quality control was carried out using the software Plink [37]. To account for population outliers and correct for differential ancestry between cases and controls that may exist in the dataset after familial outlier removal, a principal component (PC) analysis was conducted using the EIGENSTRAT software (Broad Institute, Boston, MA, USA) [38].

A total of 617 ER-negative cases and 4,583 controls passed the quality control for samples. The 285,984 SNPs that passed quality control filters in all sample sets were merged into a single file for analysis.

The five most strongly associated SNPs in the combined analysis, which had effects in the same direction for both studies in the discovery stage (Swedish and Finnish) were forwarded for validation in SEARCH and RBCS. Genotyping in SEARCH and RBCS was performed by 5'exonuclease assay (Taqman) using the ABI Prism 7900HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

All SNP chromosomal positions were based on NCBI Build 36.

Statistical analysis

Figure 1 gives a broad overview of the analytical strategy for the single marker association analysis and pathway analysis.

Single marker association analysis

Logistic regression models with genotype coded 0, 1, 2 and treated as a continuous covariate (one at a time), were fitted for each SNP that passed quality control. An additive genetic effect on the logit scale was assumed to characterize the associations. Separate analyses were performed for the Swedish and Finnish datasets as well as a combined analysis.

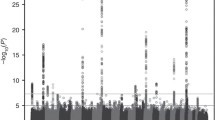

In the combined analysis, the final model included as covariates the SNP genotype, an indicator variable specifying country (Sweden and Finland), and interaction effects of Eigen values of PCs × country specified in such a way that country-specific PCs were implemented for the relevant subjects. Quantile-quantile plots were used to check for systematic genotyping error or bias due to unaccounted underlying population substructure. Manhattan plots were generated to summarize the -log transformed P-values of all SNPs examined.

Pathway analysis using discovery set (Swedish and Finnish samples)

Pathway analysis of the discovery GWAS dataset was conducted using the SNP ratio test (SRT) SRT was used to investigate the associations with breast cancer for 212 pathways and their genes (approximately 4,700) taken from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database (05/12/08) [39].

To evaluate the association between regulatory SNPs-defined pathways and ER-negative breast cancer, we used the downloadable database from mRNA by SNP Browser [40] to map SNPs, which are significantly associated with gene expression on a genome-wide level (LOD >6), to genes. In total, 7,698 SNPs were mapped to 3,740 probes with a LOD score >6. These 3,740 probes could be mapped to 2,070 genes, and out of these, 554 genes, regulated by 1,720 SNPs, were annotated as belonging to one or several of the 182 KEGG pathways.

Among five regulatory SNP-defined pathways found to be significantly associated with ER-negative breast cancer, four belonged to the pathway class "cancer". To evaluate if the abundance of small P-values from regulatory SNPs involved in cancer-related pathways was statistically significant as a whole, we also assessed the departure of the distribution of the trend test statistics from the null distribution, assuming that none of the SNPs was associated with ER-negative breast cancer as an outcome. For this purpose, we performed the "admixture maximum likelihood" test described by Tyrer et al. [41] to obtain a global P-value for 165 unique SNPs from 15 cancer-related pathways (hsa052*) curated in the KEGG database.

Analysis of shared polygenic variation between ER-negative and ER-positive breast cancer subtypes

We assessed the polygenic component of breast cancer risk using a procedure for creating sample scores which has been described elsewhere [42]. Briefly, ER-positive breast cancer cases and healthy controls from either the Finnish or Swedish study were used as a "training set" to derive a list of SNPs used for scoring in two "target sets", consisting of either ER-positive breast cancer cases and healthy controls or ER-negative breast cancer cases and healthy controls in the other population. Figure 2 gives a broad overview of the analytical strategy for assessing common polygenic variation.

The polygenic score for each individual was calculated by summing the number of score alleles weighed by the log of their odds ratio from the training sample, across all SNPs included in the score. SNPs were included in the score if they achieved a P-value less than a particular threshold in the training sample. The "---score" function in Plink [37] was used to calculate scores. To capture association signals with very small effects in the calculation of the polygenic component of the disease, we used non-stringent significance thresholds (P < 0.01, P < 0.05, P < 0.10, P < 0.20, P < 0.30, P < 0.40 and P < 0.50). Scores were calculated for the seven P-value thresholds.

The extent of shared polygenic variation between ER-positive breast cancers in the training sample and ER-positive and ER-negative breast cancers in the corresponding target samples was assessed by fitting logistic regression models to disease state, as a function of score, in the target samples. Regression models, adjusted for the number of non-missing genotypes, were fitted to assess the differences in the extent of shared polygenic variation (scores) between the ER-positive and ER-negative target samples in case-only analyses.

PLINK (v1.06) [37], SNP Ratio Test [19], R (v2.8.0) [43], Quanto [44], AML [41], Qlikview (v8.5) [45], HaploView [46] and LocusZoom [47] were used for data management, quality control, statistical analyses, and graphics. All reported tests are two-sided.

Results

In this study, we tested the association of 285,984 loci with ER-negative breast cancer in two independent populations consisting of a total of 617 cases and 4,583 controls. It appears that the overall population substructure was adequately accounted for, since a systematic deviation from the expected distribution was not observed in the quantile-quantile plot (Supplementary Figures 2, 3 and 4 in Additional file 2). Quantile-quantile plots generated from the analyses of individual datasets showed that there was no within-study systematic error arising from the use of non-matched population controls or genotyping at different facilities (Supplementary Figures 2 and 3 in Additional file 2). Genotype cluster plots were examined for SNPs with P < 10-5. Manual reclustering was performed for six SNPs with poor genotype cluster plots. SNPs rs4660646 and rs2462692 were omitted from further analysis as they could not be reclustered. SNPs rs4549482, rs1984492, rs1389545 and rs3748648 were not found to be strongly associated with ER-negative breast cancer after reclustering (Table S1 in Additional file 3).

Figure 3 shows a Manhattan plot summarizing the -log-transformed P-values of 285,984 SNPs analyzed in this study. In a combined analysis of individuals of Swedish and Finnish backgrounds, the strongest association with ER-negative breast cancer below the threshold for genome-wide significance was for a locus marked by rs361147 on chromosome 4 (P trend = 3.13 × 10-13; OR per allele = 0.60) (Table S2 in Additional file 3). This was the only SNP to achieve statistical significance at the genome-wide level (α = 5 × 10-8). Overall, no significant signal peak was identified in this study (Figures 4, 5, 6, 7, 8).

Nevertheless, we selected five SNPs to be validated in a combined dataset of two independent studies (Table S2 in Additional file 3). SNPs rs7039994 and rs12000794, located 106310 base pairs away from each other on chromosome 9, were found to be in high LD (r2 = 0.797; D' = 0.952). The former was kept and validated in the SEARCH dataset as its associated P-value was smaller and it was in closer proximity to coding regions (downstream of INVS|TEX10). SNP rs3777218 was selected over rs11882068 due to a better regional signal peak. Other SNPs selected for validation included rs361147 as mentioned above, rs6993922, rs4726078 (within transcript of PRKAG2), and rs3777218 (within transcript of RHOBTB3). Of the five SNPs forwarded for validation, rs4726078 could not be designed and was replaced by rs10952315 (r2 = 0.977 in Centre d'Etude du Polymorphisme Humain (CEPH) from Utah (CEU) HapMap samples). None of the SNPs was significantly associated at the 5% level in the second stage. The smallest P-value obtained was for the surrogate rs10952315 (OR 1.02; 95% CI: 0.93 to 1.13).

To analyze our GWAS data in a pathway context we conducted a permutation-based analysis using the KEGG database. Pathways defined by SNPs located within transcript of genes that were found to be significantly associated with ER-negative breast cancer after 1,000 phenotype permutations at a threshold of Pα = 0.05 < 0.05 (uncorrected) were: pentose and glucuronate interconversions (hsa00040) (P = 0.022), starch and sucrose metabolism (hsa00500) (P = 0.042), and gap junction (hsa04540) (P = 0.037) (Table 2).

In addition, we limited the analysis to pathway definitions involving only known regulatory SNPs [48]. The GWAS SNPs were first mapped to genes, and then subsequently to KEGG pathways based on publicly available gene regulatory data from lymphoblastoid cells [48]. Only genes with regulatory functions significant on a genome-wide significant level were selected, resulting in 1,720 SNPs regulating members of 182 KEGG pathways being used in our analysis. Pathways that were found to be significant by SRT after 1,000 phenotype permutations at a threshold of Pα = 0.05 < 0.05 were: long-term potentiation (hsa04720), glioma (hsa05214), non-small cell lung cancer (hsa05223), pancreatic cancer (hsa05212), and prostate cancer (hsa5215) (Table 3). The focal adhesion pathway (hsa04510) was found to be marginally significant (Pα = 0.05 = 0.052). Two pathways each tagged by only a single SNP, glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism (hsa00630) and glycosphingolipid biosynthesis - ganglio series (hsa00604), were removed from the evaluation of the final results.

Regulatory SNPs involved in pathways associated with cancer (hsa052*) appeared to be overrepresented by small P-values (Figure 9). To evaluate if the combined effect of these signals was statistically significant as a whole, we next carried out a global test of significance for all unique SNPs in the cancer pathways. The AML analysis performed using an algorithm developed by Tyrer et al. [41], yielded P-values (α = 0.05) of 0.0028 (crude) and 0.052 (adjusted for population stratification).

Distribution of P -values of regulatory SNPs within KEGG cancer pathways (pathway identifiers beginning with hsa052*). *Global P-values of cancer-related regulatory SNPs with P < 0.05 in the genome-wide association analysis using the admixture maximum likelihood test (5,000 permutations) are 0.0028 (unadjusted), and 0.052 (with adjustments made to correct for population stratification).

Figure 10 shows the results of analyses aimed at assessing the shared polygenic component between ER-positive and ER-negative breast cancer. Estimates of variance explained in datasets indicate how important the polygenic component of ER-positive disease is in explaining the overall occurrence of ER-positive and ER-negative diseases. The proportion of variance explained for all categories of P-value cut-offs, with the exception of P < 0.05 in the Swedish ER-positive target sample, was higher in the ER-positive target datasets than the ER-negative target datasets.

Proportion of shared polygenic component between breast cancer estrogen receptor subtypes. Proportion of shared polygenic component between ER-positive and ER-negative target samples, with respect to their corresponding ER-positive training samples. Pt denotes P-value cut-off in training sample. a) Test for association between polygenic score and disease status (ER-positive/ER-negative) in the Swedish data, when all SNPs with P < 0.5 in the Finnish training set were considered. b) Test for association between polygenic score and disease status (ER-positive/ER-negative) in the Finnish data, when all SNPs with P < 0.5 in the Swedish training set were considered. c) Significance test for difference in scores (Finnish ER-positive breast cancers derived) between Swedish ER-negative and ER-positive breast cancers, adjusted for number of non-missing genotypes. Significance codes: '- ' 0.1 <P < 1 (that is, not significant). d) Significance test for difference in scores (Swedish ER-positive breast cancers derived) between Finnish ER-negative and ER-positive breast cancers, adjusted for number of non-missing genotypes. Significance codes: '*' 0.01 <P < 0.05.

We test for association between polygenic score and disease status (ER-positive vs controls/ER-negative vs controls) in the target data, when seven groups of SNPs with different P-values thresholds in the training sets were considered (Figure 10a, b). Due possibly to limited statistical power (Table S3 in Additional file 3), even at the least stringent P-value threshold (P < 0.50), the ER-positive and ER-negative breast cancer target case-control datasets failed to provide statistically significant evidence of a polygenic component for ER-positive cancer, or evidence of a polygenic component shared between the two cancers, when training was based on the ER-positive training case-control datasets (Figure 10a, b). Nevertheless, when we relaxed the P-value cut-off in the training dataset to 0.5, the Swedish ER-positive breast cancer target dataset showed borderline significance for a shared polygenic component with ER-positive breast cancer, based on the Finnish ER-positive training dataset (Figure 10a, P = 0.066).

In a separate case-only analysis, we performed a significance test for difference in scores between ER-positive and ER-negative breast cancer cases in the target data. Significant results show that ER-positive and ER-negative breast cancers are not identical diseases (genetically at polygenic level) (Figures 10c, d). The difference in scores between ER-positive and ER-negative samples was found to be statistically significant for all categories of P-value cut-offs in the Finnish target case-only samples, with the exception of the most associated SNPs (Figure 10d).

Discussion

Little is known about the genetic predisposition to estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. This subtype is characterized by lower age of onset, a more aggressive disease and low or no response to selective estrogen receptor modulators or aromatase inhibitors. We have examined our GWAS data on two different levels: single marker and pathway. We also provided evidence that breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease with a polygenic nature, with significant differences between the polygenic component between ER-positive and ER-negative breast cancers. This emphasizes the importance of looking at ER-negative breast cancer separately as a unique breast cancer phenotype.

Overall, no significant signal peak was identified in this study (Figures 4, 5, 6, 7, 8). Only one SNP (rs361147) was found to achieve genome-wide significance after correction for multiple testing in the single marker analysis. However, the other loci exhibiting strong associations were interesting for reasons of biological significance, and were considered to merit further research. The associated region on 9q31.1 tagged by rs7039994 contains two known genes, TEX10 (testis expressed sequence 10) and INVS (inversin). No function has been ascribed to TEX10. INVS is reported to function as a molecular switch between different Wnt signalling pathways [49] and is also pivotal in the establishment of the left-right axis. The RHOBTB3 gene, harbouring SNP rs3777218, was identified as a putative breast cancer anti-estrogen resistance gene [50]. However, none of these single markers most strongly associated with ER-negative breast cancer could be replicated in a larger, independent sample made up of two independent studies (Table 1)

To maximize the information obtained from the GWAS scan, we conducted a permutation-based pathway analysis using the KEGG database to capture the joint actions of multiple SNPs with modest effects. In the analysis using default SRT pathway definition files comprising within-transcript SNPs, metabolic pathways involving pentose and glucuronate interconversions (hsa00040) (P = 0.022) as well as starch and sucrose metabolism (hsa00500) (P = 0.042) were found to be nominally significantly related to the risk of developing ER-negative breast cancer (Table 2). Estrogen-induced breast cancer cell proliferation is often accompanied by an increase in intracellular metabolic activity, resulting in a higher growth rate. The pentose phosphate pathway, which works in tight conjunction with the pentose and glucuronate interconversions and starch and sucrose metabolism pathways, has recently been suggested to be essential for estrogen-dependent cell proliferation [51]. Several pathways that were found to be marginally significant (P < 0.1) have been suggested to have potential roles in ER-negative breast cancer, namely, the TGF-beta signalling pathway [52], the renin-angiotensin system [53], and the Notch signalling pathway [54]. In addition, the insulin signalling pathway has been the focus of targeted therapy for breast cancer [55], and the purine metabolism pathway is also closely related to the pentose phosphate pathway described earlier.

Nevertheless, there is neither a precise biological definition of a pathway, nor a "standard" method to map SNPs to genes, and then genes to pathways. Pathway analyses of GWAS of common diseases have mostly based SNP-to-gene mappings on the chromosomal position of the SNP, whether it occurs within transcript of a certain gene [19, 56]. However, it may be more meaningful to map SNPs that are associated with the expression of a gene to the gene. To elucidate pathways with more biological relevance, we further conducted pathway analysis based on a subset of SNPs with known regulatory functions. Recent studies have observed that whereas stronger effects overlap between different tissues, weak effects on gene regulation are tissue-specific [57, 58]. Since we utilized data on gene regulation from lymphoblasts, we decided to restrict our dataset to only genes regulated on a genome-wide significant level (LOD >6). This minimized the bias of tissue-specific gene regulation, but at the same time, limited us to only a fraction of all possible SNPs genotyped within our GWAS, thus reducing the power of the analysis.

In spite of the limitations, four of the five significantly associated pathways (P < 0.05) in our analysis were found to be annotated as cancer pathways in KEGG (glioma (hsa05214), non-small cell lung cancer (hsa05223), pancreatic cancer (hsa05212), and prostate cancer (hsa05215) (Table 3)), hence confirming the validity of the choice of this subset of regulatory SNPs in pathway definition. In addition, a global test of the SNPs defining the cancer pathways found the aggregate effect to be approaching statistical significance (Pα = 0.05 = 0.052). Due to the large number of markers evaluated in a genome-wide scan, signals with small effects and modestly significant P-values are likely to be dismissed after the correction of multiple testing. The implementation of a pathway analysis thus serves as a complementation between a hypothesis-driven (prior knowledge of biological pathways) and a hypothesis-free (genome-wide scan) approach to highlight certain markers, such as those found in the cancer pathways, worthy of further study that would not have been examined otherwise. The lack of a concordance between the results of pathway analyses using two different SNP-to-gene mapping approaches emphasizes the need to put in more consideration in choosing appropriate pathway definitions. An excess of small P-values found for SNPs associated with gene expression involved in cancer-related pathways suggests that the SNP-gene mapping via association with gene expression approach is superior to the SNP-gene mapping by location within a transcript approach, and should be explored in greater detail.

Limitations of this study include an overall lack of statistical power, especially for the single marker analysis, and the existence of further heterogeneity among ER-negative tumours. Although genome-wide pathway-based analysis is an interesting approach, a main limitation is that the associations observed in this study are only nominally significant, and would not be significant after correction for multiple testing. However, as many pathways have SNPs in common with other pathways, the stringent significance thresholds of traditional multiple testing correction methods are potentially over-conservative. There is also indirect evidence that corroborates our pathway findings. Gene expression studies have found pathways related to the renin-angiotensin system and focal adhesion to be significantly associated with prognosis of breast cancer [59]. Others have also reported pathways highlighted in our study, which are involved in pentose and glucuronate interconversions, gap junction, TGF-beta signalling, rennin-angiotensin system, B cell receptor signalling, Fc epsilon RI signalling, VEGF signalling, ErbB signalling, and focal adhesion, to be significantly associated with the breast cancer phenotype [59, 60]. Although replication of the pathway results in independent studies would be needed to confirm the associations, the substantial additional sample collection and genotyping required are beyond the scope of this publication.

Although breast cancer has been classified into ER-positive and ER-negative breast cancers, and these two breast cancer subtypes have been documented to show different gene expression patterns, GWAS scans on breast cancer have always been performed on either overall breast cancer (ER-positive, ER-negative and unknown) or ER-positive breast cancer specific risks. In this study, we found evidence to suggest that ER-negative breast cancers only share a fraction of the polygenic component of the disease with ER-positive breast cancers, implying that ER-negative breast cancer should be examined as a distinct breast cancer phenotype. Although the difference between the polygenic components of ER-positive and ER-negative breast cancers was found only to be significant in the Finnish training samples, we observed similar differences for all seven P-value thresholds in the Swedish training samples. However, due to the smaller number of Swedish ER-negative cases (N = 153, approximately 33% of Finnish ER-negative cases), we had less power to detect significant heterogeneity between the two subtypes in the Swedish target samples.

Conclusions

Given the clinical importance of the ER-negative phenotype and the likelihood that the relative genetic effect sizes are small, greater sample sizes and further studies are required to further the knowledge on ER-negative breast cancers. Identification of factors for a predisposition to ER-negative tumours opens the way for understanding the underlying etiology of the disease, and may ultimately result in improvements in prevention, early detection and specific treatment for this tumour subtype. We used a novel approach to pathway analysis, showing that established cancer pathways could be regulated by common variants associated to ER-negative breast cancer. We also provided molecular genetic evidence which suggests that ER-negative breast cancer is a distinct breast cancer subtype that merits independent analyses. In view of the biological relevance of the pathways identified, a genome-wide pathway approach deserves merit, and has good potential in pointing out directions for future research for ER-negative breast cancers.

Abbreviations

- Λ:

-

genomic control inflation factor

- AML:

-

admixture maximum likelihood

- EIRA:

-

Epidemiological Investigation of Rheumatoid Arthritis

- ER:

-

estrogen receptor

- GWAS:

-

genome-wide association study

- HWE:

-

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- LD:

-

linkage disequilibrium

- MAF:

-

minor allele frequency

- NCBI:

-

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- PC:

-

principal component

- PCA:

-

principal component analysis

- RBCS:

-

Rotterdam Breast Cancer Study

- SEARCH:

-

Study of Epidemiology and Risk factors in Cancer Heredity

- SNP:

-

single nucleotide polymorphism

- SRT:

-

SNP ratio test.

References

Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, Pollack JR, Ross DT, Johnsen H, Akslen LA, Fluge O, Pergamenschikov A, Williams C, Zhu SX, Lonning PE, Borresen-Dale AL, Brown PO, Botstein D: Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000, 406: 747-752.

Sorlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, Aas T, Geisler S, Johnsen H, Hastie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Thorsen T, Quist H, Matese JC, Brown PO, Botstein D, Eystein Lonning P, Borresen-Dale AL: Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001, 98: 10869-10874.

Lichtenstein P, Holm NV, Verkasalo PK, Iliadou A, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M, Pukkala E, Skytthe A, Hemminki K: Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer--analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N Engl J Med. 2000, 343: 78-85.

Thomas G, Jacobs KB, Kraft P, Yeager M, Wacholder S, Cox DG, Hankinson SE, Hutchinson A, Wang Z, Yu K, Chatterjee N, Garcia-Closas M, Gonzalez-Bosquet J, Prokunina-Olsson L, Orr N, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Ziegler RG, Berg CD, Buys SS, McCarty CA, Feigelson HS, Calle EE, Thun MJ, Diver R, Prentice R, Jackson R, Kooperberg C, Chlebowski R, Lissowska J, et al: A multistage genome-wide association study in breast cancer identifies two new risk alleles at 1p11.2 and 14q24.1 (RAD51L1). Nat Genet. 2009, 41: 579-584.

Easton DF, Pooley KA, Dunning AM, Pharoah PD, Thompson D, Ballinger DG, Struewing JP, Morrison J, Field H, Luben R, Wareham N, Ahmed S, Healey CS, Bowman R, Meyer KB, Haiman CA, Kolonel LK, Henderson BE, Le Marchand L, Brennan P, Sangrajrang S, Gaborieau V, Odefrey F, Shen CY, Wu PE, Wang HC, Eccles D, Evans DG, Peto J, Fletcher O, et al: Genome-wide association study identifies novel breast cancer susceptibility loci. Nature. 2007, 447: 1087-1093.

Cox A, Dunning AM, Garcia-Closas M, Balasubramanian S, Reed MW, Pooley KA, Scollen S, Baynes C, Ponder BA, Chanock S, Lissowska J, Brinton L, Peplonska B, Southey MC, Hopper JL, McCredie MR, Giles GG, Fletcher O, Johnson N, dos Santos Silva I, Gibson L, Bojesen SE, Nordestgaard BG, Axelsson CK, Torres D, Hamann U, Justenhoven C, Brauch H, Chang-Claude J, Kropp S, et al: A common coding variant in CASP8 is associated with breast cancer risk. Nat Genet. 2007, 39: 352-358.

Hunter DJ, Kraft P, Jacobs KB, Cox DG, Yeager M, Hankinson SE, Wacholder S, Wang Z, Welch R, Hutchinson A, Wang J, Yu K, Chatterjee N, Orr N, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Ziegler RG, Berg CD, Buys SS, McCarty CA, Feigelson HS, Calle EE, Thun MJ, Hayes RB, Tucker M, Gerhard DS, Fraumeni JF, Hoover RN, Thomas G, Chanock SJ: A genome-wide association study identifies alleles in FGFR2 associated with risk of sporadic postmenopausal breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2007, 39: 870-874.

Stacey SN, Manolescu A, Sulem P, Rafnar T, Gudmundsson J, Gudjonsson SA, Masson G, Jakobsdottir M, Thorlacius S, Helgason A, Aben KK, Strobbe LJ, Albers-Akkers MT, Swinkels DW, Henderson BE, Kolonel LN, Le Marchand L, Millastre E, Andres R, Godino J, Garcia-Prats MD, Polo E, Tres A, Mouy M, Saemundsdottir J, Backman VM, Gudmundsson L, Kristjansson K, Bergthorsson JT, Kostic J, et al: Common variants on chromosomes 2q35 and 16q12 confer susceptibility to estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2007, 39: 865-869.

Stacey SN, Manolescu A, Sulem P, Thorlacius S, Gudjonsson SA, Jonsson GF, Jakobsdottir M, Bergthorsson JT, Gudmundsson J, Aben KK, Strobbe LJ, Swinkels DW, van Engelenburg KC, Henderson BE, Kolonel LN, Le Marchand L, Millastre E, Andres R, Saez B, Lambea J, Godino J, Polo E, Tres A, Picelli S, Rantala J, Margolin S, Jonsson T, Sigurdsson H, Jonsdottir T, Hrafnkelsson J, et al: Common variants on chromosome 5p12 confer susceptibility to estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2008, 40: 703-706.

Ahmed S, Thomas G, Ghoussaini M, Healey CS, Humphreys MK, Platte R, Morrison J, Maranian M, Pooley KA, Luben R, Eccles D, Evans DG, Fletcher O, Johnson N, dos Santos Silva I, Peto J, Stratton MR, Rahman N, Jacobs K, Prentice R, Anderson GL, Rajkovic A, Curb JD, Ziegler RG, Berg CD, Buys SS, McCarty CA, Feigelson HS, Calle EE, Thun MJ, et al: Newly discovered breast cancer susceptibility loci on 3p24 and 17q23.2. Nat Genet. 2009, 41: 585-590.

Zheng W, Long J, Gao YT, Li C, Zheng Y, Xiang YB, Wen W, Levy S, Deming SL, Haines JL, Gu K, Fair AM, Cai Q, Lu W, Shu XO: Genome-wide association study identifies a new breast cancer susceptibility locus at 6q25.1. Nat Genet. 2009, 41: 324-328.

Thomas D: Gene-environment-wide association studies: emerging approaches. Nat Rev Genet. 11: 259-272.

Pedroso I: Gaining a pathway insight into genetic association data. Methods Mol Biol. 628: 373-382.

Baranzini SE, Galwey NW, Wang J, Khankhanian P, Lindberg R, Pelletier D, Wu W, Uitdehaag BM, Kappos L, Polman CH, Matthews PM, Hauser SL, Gibson RA, Oksenberg JR, Barnes MR: Pathway and network-based analysis of genome-wide association studies in multiple sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2009, 18: 2078-2090.

Elbers CC, van Eijk KR, Franke L, Mulder F, van der Schouw YT, Wijmenga C, Onland-Moret NC: Using genome-wide pathway analysis to unravel the etiology of complex diseases. Genet Epidemiol. 2009, 33: 419-431.

Peng G, Luo L, Siu H, Zhu Y, Hu P, Hong S, Zhao J, Zhou X, Reveille JD, Jin L, Amos CI, Xiong M: Gene and pathway-based second-wave analysis of genome-wide association studies. Eur J Hum Genet. 18: 111-117.

Ritchie MD: Using prior knowledge and genome-wide association to identify pathways involved in multiple sclerosis. Genome Med. 2009, 1: 65-

Wang K, Li M, Bucan M: Pathway-based approaches for analysis of genomewide association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2007

O'Dushlaine C, Kenny E, Heron EA, Segurado R, Gill M, Morris DW, Corvin A: The SNP ratio test: pathway analysis of genome-wide association datasets. Bioinformatics. 2009, 25: 2762-2763.

Guo YF, Li J, Chen Y, Zhang LS, Deng HW: A new permutation strategy of pathway-based approach for genome-wide association study. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009, 10: 429-

Garcia-Closas M, Chanock S: Genetic susceptibility loci for breast cancer by estrogen receptor status. Clin Cancer Res. 2008, 14: 8000-8009.

Mavaddat N, Pharoah PD, Blows F, Driver KE, Provenzano E, Thompson D, Macinnis RJ, Shah M, Easton DF, Antoniou AC: Familial relative risks for breast cancer by pathological subtype: a population-based cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 12: R10-

Lesueur F, Pharoah PD, Laing S, Ahmed S, Jordan C, Smith PL, Luben R, Wareham NJ, Easton DF, Dunning AM, Ponder BA: Allelic association of the human homologue of the mouse modifier Ptprj with breast cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2005, 14: 2349-2356.

Magnusson C, Baron J, Persson I, Wolk A, Bergstrom R, Trichopoulos D, Adami HO: Body size in different periods of life and breast cancer risk in post-menopausal women. Int J Cancer. 1998, 76: 29-34.

Rosenberg LU, Einarsdottir K, Friman EI, Wedren S, Dickman PW, Hall P, Magnusson C: Risk factors for hormone receptor-defined breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006, 15: 2482-2488.

Li J, Humphreys K, Heikkinen T, Aittomaki K, Blomqvist C, Pharoah PD, Dunning AM, Ahmed S, Hooning MJ, Martens JW, van den Ouweland AM, Alfredsson L, Palotie A, Peltonen-Palotie L, Irwanto A, Low HQ, Teoh GH, Thalamuthu A, Easton DF, Nevanlinna H, Liu J, Czene K, Hall P: A combined analysis of genome-wide association studies in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat.

Plenge RM, Seielstad M, Padyukov L, Lee AT, Remmers EF, Ding B, Liew A, Khalili H, Chandrasekaran A, Davies LR, Li W, Tan AK, Bonnard C, Ong RT, Thalamuthu A, Pettersson S, Liu C, Tian C, Chen WV, Carulli JP, Beckman EM, Altshuler D, Alfredsson L, Criswell LA, Amos CI, Seldin MF, Kastner DL, Klareskog L, Gregersen PK: TRAF1-C5 as a risk locus for rheumatoid arthritis--a genomewide study. N Engl J Med. 2007, 357: 1199-1209.

Syrjakoski K, Vahteristo P, Eerola H, Tamminen A, Kivinummi K, Sarantaus L, Holli K, Blomqvist C, Kallioniemi OP, Kainu T, Nevanlinna H: Population-based study of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in 1035 unselected Finnish breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000, 92: 1529-1531.

Kilpivaara O, Bartkova J, Eerola H, Syrjakoski K, Vahteristo P, Lukas J, Blomqvist C, Holli K, Heikkila P, Sauter G, Kallioniemi OP, Bartek J, Nevanlinna H: Correlation of CHEK2 protein expression and c.1100delC mutation status with tumor characteristics among unselected breast cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2005, 113: 575-580.

Fagerholm R, Hofstetter B, Tommiska J, Aaltonen K, Vrtel R, Syrjakoski K, Kallioniemi A, Kilpivaara O, Mannermaa A, Kosma VM, Uusitupa M, Eskelinen M, Kataja V, Aittomaki K, von Smitten K, Heikkila P, Lukas J, Holli K, Bartkova J, Blomqvist C, Bartek J, Nevanlinna H: NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 NQO1*2 genotype (P187S) is a strong prognostic and predictive factor in breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2008, 40: 844-853.

Eerola H, Blomqvist C, Pukkala E, Pyrhonen S, Nevanlinna H: Familial breast cancer in southern Finland: how prevalent are breast cancer families and can we trust the family history reported by patients?. Eur J Cancer. 2000, 36: 1143-1148.

Bilguvar K, Yasuno K, Niemela M, Ruigrok YM, von Und Zu Fraunberg M, van Duijn CM, van den Berg LH, Mane S, Mason CE, Choi M, Gaal E, Bayri Y, Kolb L, Arlier Z, Ravuri S, Ronkainen A, Tajima A, Laakso A, Hata A, Kasuya H, Koivisto T, Rinne J, Ohman J, Breteler MM, Wijmenga C, State MW, Rinkel GJ, Hernesniemi J, Jaaskelainen JE, Palotie A, et al: Susceptibility loci for intracranial aneurysm in European and Japanese populations. Nat Genet. 2008, 40: 1472-1477.

Aulchenko YS, Ripatti S, Lindqvist I, Boomsma D, Heid IM, Pramstaller PP, Penninx BW, Janssens AC, Wilson JF, Spector T, Martin NG, Pedersen NL, Kyvik KO, Kaprio J, Hofman A, Freimer NB, Jarvelin MR, Gyllensten U, Campbell H, Rudan I, Johansson A, Marroni F, Hayward C, Vitart V, Jonasson I, Pattaro C, Wright A, Hastie N, Pichler I, Hicks AA, et al: Loci influencing lipid levels and coronary heart disease risk in 16 European population cohorts. Nat Genet. 2009, 41: 47-55.

Sabatti C, Service SK, Hartikainen AL, Pouta A, Ripatti S, Brodsky J, Jones CG, Zaitlen NA, Varilo T, Kaakinen M, Sovio U, Ruokonen A, Laitinen J, Jakkula E, Coin L, Hoggart C, Collins A, Turunen H, Gabriel S, Elliot P, McCarthy MI, Daly MJ, Jarvelin MR, Freimer NB, Peltonen L: Genome-wide association analysis of metabolic traits in a birth cohort from a founder population. Nat Genet. 2009, 41: 35-46.

Leu M, Humphreys K, Surakka I, Rehnberg E, Muilu J, Rosenström P, Almgren P, Jääskeläinen J, Lifton RP, Kyvik KO, Kaprio J, Pedersen NL, Palotie A, Hall P, Grönberg H, Groop L, Peltonen L, Palmgren J, Ripatti S: NordicDB: A Nordic pool and portal for genome-wide control data. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010,

Duerr RH, Taylor KD, Brant SR, Rioux JD, Silverberg MS, Daly MJ, Steinhart AH, Abraham C, Regueiro M, Griffiths A, Dassopoulos T, Bitton A, Yang H, Targan S, Datta LW, Kistner EO, Schumm LP, Lee AT, Gregersen PK, Barmada MM, Rotter JI, Nicolae DL, Cho JH: A genome-wide association study identifies IL23R as an inflammatory bowel disease gene. Science. 2006, 314: 1461-1463.

Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, Sham PC: PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007, 81: 559-575.

Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D: Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006, 38: 904-909.

Kanehisa M, Goto S: KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28: 27-30.

mRNA by SNP Browser v 1.0.1. [http://www.sph.umich.edu/csg/liang/asthma/]

Tyrer J, Pharoah PD, Easton DF: The admixture maximum likelihood test: a novel experiment-wise test of association between disease and multiple SNPs. Genet Epidemiol. 2006, 30: 636-643.

Purcell SM, Wray NR, Stone JL, Visscher PM, O'Donovan MC, Sullivan PF, Sklar P: Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature. 2009, 460: 748-752.

R Development Core Team: R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. 2007, Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing

QUANTO 1.1: A computer program for power and sample size calculations for genetic-epidemiology studies. [http://hydra.usc.edu/gxe]

Qlikview. [http://www.qliktech.com]

Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ: Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005, 21: 263-265.

Pruim RJ, Welch RP, Sanna S, Teslovich TM, Chines PS, Gliedt TP, Boehnke M, Abecasis GR, Willer CJ: LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics. 2010, 26: 2336-2337.

Dixon AL, Liang L, Moffatt MF, Chen W, Heath S, Wong KC, Taylor J, Burnett E, Gut I, Farrall M, Lathrop GM, Abecasis GR, Cookson WO: A genome-wide association study of global gene expression. Nat Genet. 2007, 39: 1202-1207.

Simons M, Gloy J, Ganner A, Bullerkotte A, Bashkurov M, Kronig C, Schermer B, Benzing T, Cabello OA, Jenny A, Mlodzik M, Polok B, Driever W, Obara T, Walz G: Inversin, the gene product mutated in nephronophthisis type II, functions as a molecular switch between Wnt signaling pathways. Nat Genet. 2005, 37: 537-543.

van Agthoven T, Veldscholte J, Smid M, van Agthoven TL, Vreede L, Broertjes M, de Vries I, de Jong D, Sarwari R, Dorssers LC: Functional identification of genes causing estrogen independence of human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009, 114: 23-30.

Forbes NS, Meadows AL, Clark DS, Blanch HW: Estradiol stimulates the biosynthetic pathways of breast cancer cells: detection by metabolic flux analysis. Metab Eng. 2006, 8: 639-652.

Biswas S, Guix M, Rinehart C, Dugger TC, Chytil A, Moses HL, Freeman ML, Arteaga CL: Inhibition of TGF-beta with neutralizing antibodies prevents radiation-induced acceleration of metastatic cancer progression. J Clin Invest. 2007, 117: 1305-1313.

Herr D, Rodewald M, Fraser HM, Hack G, Konrad R, Kreienberg R, Wulff C: Potential role of Renin-Angiotensin-system for tumor angiogenesis in receptor negative breast cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2008, 109: 418-425.

Dontu G, Jackson KW, McNicholas E, Kawamura MJ, Abdallah WM, Wicha MS: Role of Notch signaling in cell-fate determination of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2004, 6: R605-615.

Zeng X, Yee D: Insulin-like growth factors and breast cancer therapy. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007, 608: 101-112.

Menashe I, Maeder D, Garcia-Closas M, Figueroa JD, Bhattacharjee S, Rotunno M, Kraft P, Hunter DJ, Chanock SJ, Rosenberg PS, Chatterjee N: Pathway analysis of breast cancer genome-wide association study highlights three pathways and one canonical signaling cascade. Cancer Res. 70: 4453-4459.

Dimas AS, Deutsch S, Stranger BE, Montgomery SB, Borel C, Attar-Cohen H, Ingle C, Beazley C, Gutierrez Arcelus M, Sekowska M, Gagnebin M, Nisbett J, Deloukas P, Dermitzakis ET, Antonarakis SE: Common regulatory variation impacts gene expression in a cell type-dependent manner. Science. 2009, 325: 1246-1250.

Kwan T, Grundberg E, Koka V, Ge B, Lam KC, Dias C, Kindmark A, Mallmin H, Ljunggren O, Rivadeneira F, Estrada K, van Meurs JB, Uitterlinden A, Karlsson M, Ohlsson C, Mellstrom D, Nilsson O, Pastinen T, Majewski J: Tissue effect on genetic control of transcript isoform variation. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5: e1000608-

Ma S, Kosorok MR: Detection of gene pathways with predictive power for breast cancer prognosis. BMC Bioinformatics. 11: 1-

Gohlke JM, Thomas R, Zhang Y, Rosenstein MC, Davis AP, Murphy C, Becker KG, Mattingly CJ, Portier CJ: Genetic and environmental pathways to complex diseases. BMC Syst Biol. 2009, 3: 46-

Acknowledgements

The Swedish study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (RO1 CA58427 to PH and JLiu), the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR; Singapore), the Nordic Cancer Society, Märit and Hans Rausing's Initiative against Breast Cancer, and the Cancer Risk Prediction Center (CRisP), a LinneusCentre (Contract ID 70867902) financed by the Swedish researchCouncil. J Li is a recipient of an A*STAR Graduate Scholarship (Overseas) award. KH was supported by the Swedish Research Council (523-2006-972). KC was supported by the Swedish Cancer Society (5128-B07-01PAF). The Helsinki study was supported by the Nordic Cancer Society, the Helsinki University Central Hospital Research Fund, the Academy of Finland (132473), the Finnish Cancer Society and the Sigrid Juselius Foundation. We thank Dr. Kirsimari Aaltonen and RN Hanna Jäntti for their help with the patient data. The SEARCH study was funded by Cancer Research UK. DFE is a Principal Research Fellow of Cancer Research UK. We thank the SEARCH team and Eastern Cancer Registry and Information Centre (ECRIC) for recruitment of the SEARCH cases. The RBCS was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society (grant DDHK 2004-3124). We acknowledge the clinicians from the Rotterdam Family Cancer Clinic who were involved in collecting the RBCS samples: C. Seynaeve, J. Klijn, J. Collee, and R. Oldenburg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JLi, KH, HN, JLiu, KC, and PH conceived and designed the experiments. JLi, KH, HD, UH, TH, AI, HQL, GHKT, AT and GR analyzed the data. KA, CB, PDPP, AMD, DA, MJH, AH, RAO, LA, AP, LPP, JK, MD, DFE, HN, JLiu, KC and PH contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. JLi, KH, HD, GR, UH, TH, KA, CB, PDPP, AMD, DA, MJH, AH, RAO, LA, AP, LPP, AI, HQL, GHKT, AT, JK, MD, DFE, HN, JLiu, KC and PH wrote the paper.

Electronic supplementary material

13058_2010_2751_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Additional file 2: Supplementary figures. Supplementary Figure 1. Scree plot of log-transformed Eigen values. Vertical dashed lines indicate three and five PCs taken to correct for population stratification within the Swedish and Finnish populations respectively. Supplementary Figure 2. Quantile-quantile plot for 285,984 SNP trend tests, adjusted for population stratification using three principal components (Swedish subjects only). Genomic control inflation factor (λ) = 1.0140. Supplementary Figure 3. Quantile-quantile plot for 285,984 SNP trend tests, adjusted for population stratification using five principal components (Finnish subjects only). Genomic control inflation factor (λ) = 1.0137. Supplementary Figure 4. Quantile-quantile plot for 285,984 SNP trend tests, adjusted for population stratification (combined analysis of Swedish and Finnish subjects). Genomic control inflation factor (λ) = 1.0218. (PDF 63 KB)

13058_2010_2751_MOESM3_ESM.pdf

Additional file 3: Supplementary tables. Table S1. Association analysis results of reclustered SNPs. Table S2. Association results of top hits in the combined analysis, with corresponding MAF, ORs and P values within the Swedish and Finnish populations. * denotes the five SNPs selected for validation in SEARCH and RBCS. Table S3. Power to detect single marker effects in genome-wide association study. (PDF 33 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Humphreys, K., Darabi, H. et al. A genome-wide association scan on estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 12, R93 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr2772

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr2772