Abstract

Diffuse optical spectroscopy (DOS) and diffuse optical imaging (DOI) are non-invasive diagnostic techniques that employ near-infrared (NIR) light to quantitatively characterize the optical properties of centimeter-thick, multiple-scattering tissues. Although NIR was first applied to breast diaphanography more than 70 years ago, quantitative optical methods employing time- or frequency-domain 'photon migration' technologies have only recently been used for breast imaging. Because their performance is not limited by mammographic density, optical methods can provide new insight regarding tissue functional changes associated with the appearance, progression, and treatment of breast cancer, particularly for younger women and high-risk subjects who may not benefit from conventional imaging methods. This paper reviews the principles of diffuse optics and describes the development of broadband DOS for quantitatively measuring the optical and physiological properties of thick tissues. Clinical results are shown highlighting the sensitivity of diffuse optics to malignant breast tumors in 12 pre-menopausal subjects ranging in age from 30 to 39 years and a patient undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced breast cancer. Significant contrast was observed between normal and tumor regions of tissue for deoxy-hemoglobin (p = 0.005), oxy-hemoglobin (p = 0.002), water (p = 0.014), and lipids (p = 0.0003). Tissue hemoglobin saturation was not found to be a reliable parameter for distinguishing between tumor and normal tissues. Optical data were converted into a tissue optical index that decreased 50% within 1 week in response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. These results suggest a potential role for diffuse optics as a bedside monitoring tool that could aid the development of new strategies for individualized patient care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although mammography is the primary clinical imaging modality used to detect breast cancer, limitations in both sensitivity and specificity, particularly in younger and high-risk women, have led to the development of alternative techniques. Overall, mammography has reduced sensitivity in pre-menopausal women [1] and is not clinically advantageous for women under 35 years of age [2]. A general consensus has emerged that mammography is not recommended for women less than 40 years of age, and in the 40 to 50 year old population there is uncertainly regarding its effectiveness. Additional complications arise due to the fact that in pre-menopausal women, mammographic density and false negative rates are greater during the luteal versus follicular phase of the menstrual cycle [3]. Similarly, the use of hormone replacement therapy in post-menopausal women is known to increase mammographic density [4] and has been shown to impede the effectiveness of mammographic screening [5, 6]. In practical terms, up to 10% of all breast cancers, roughly 20,000 cases per year in the US, are not discovered by X-ray mammography [7]. Consequently, new detection technologies are needed that can overcome the limitations of high radiographic density.

The use of near infrared (NIR) optical methods as a supplement to conventional techniques for diagnosing and detecting breast cancer has generated considerable interest. Optical methods are advantageous because they are non-invasive, fast, relatively inexpensive, pose no risk of ionizing radiation, and NIR light can easily penetrate centimeter-thick tissues. Several groups have employed optical methods to measure subtle physiological differences in healthy breast tissue [8–13], to detect tumors [14–22], and to measure tumor response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy [23–25]. Differences in optical signatures between tissues are manifestations of multiple physiological changes associated with factors such as vascularization, cellularity, oxygen consumption, edema, fibrosis, and remodeling.

The primary limitation of optical methods is related to the fact that multiple-scattering dominates NIR light propagation in thick tissues, making quantitative measurements of optical coherence impossible. In this 'diffusion regime', light transport can be modeled as a diffusive process where photons behave as stochastic particles that move in proportion to a gradient, much like the bulk movement of molecules or heat. Quantitative tissue properties can only be obtained by separating light absorption from scattering, typically by using time- or frequency-domain measurements and model-based computations [26–29]. The underlying physical principle of these 'photon migration' methods is based on the fact that the probability of light absorption (i.e. molecular interactions) is 50 to 100-fold lower than light scattering due to dramatic differences in tissue scattering versus absorption lengths [30, 31].

Quantitative diffuse optical methods can be used in breast diagnostics to form images (diffuse optical imaging (DOI)) and obtain spectra (diffuse optical spectroscopy (DOS)). DOI and DOS are conceptually similar to the relationship between magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance spectroscopy. In general, DOI is used to form images of subsurface structures by combining data from a large number of source-detector 'views' (i.e. in planar or circular transmission geometry) using inverse tomographic reconstruction techniques [32]. DOI typically utilizes a limited number of optical wavelengths (e.g., two to six) and a narrow temporal bandwidth. In contrast, DOS employs a limited number of source-detector positions (e.g., one to two) but employs broadband content in temporal and spectral domains (i.e., hundreds of wavelengths) to recover complete absorption and scattering spectra from approximately 650 to 1,000 nm. Although an ideal DOI design would employ hundreds or thousands of source-detector pairs and wavelengths, several engineering considerations related to measurement time currently limit the practicality of this approach.

A substantial body of work has emerged over the past decade that demonstrates how tomographically based DOI methods can accurately localize subsurface structures. Optimal clinical decision-making, however, requires understanding the precise biochemical composition or 'fingerprint' of these localized inhomogeneities. This information can be obtained by fully characterizing the spectral content of breast tumors using quantitative DOS. DOS signatures are used to measure tissue hemoglobin concentration (total, oxy-, and deoxy-forms), tissue hemoglobin oxygen saturation (oxy-hemoglobin relative to the total hemoglobin), water content, lipid content and tissue scattering. Several research groups have demonstrated the sensitivity of these tissue components to breast physiology and disease [8, 10, 11, 33]. Critical challenges remain to determine the precise relationship between these quantitative measures and cancer. Consequently, this paper reviews our efforts to determine tumor biochemical composition from low-resolution spatial maps of broadband absorption and scattering spectra.

To minimize partial volume sampling effects and attribute our signals specifically to breast tumors despite high mammographic density, we have studied 12 pre-menopausal 30 to 39 year old subjects with locally advanced, stage III invasive disease, focusing on the question, "what do tumors 'look' like?" Because the biological processes that determine the origins of optical contrast are conserved across spatial scales, intrinsic optical signals measured from these subjects are expected to be similar for earlier stage disease. We highlight this population because conventional methods are generally considered to be ineffective in younger women. We also present results of DOS measurements during neoadjuvant chemotherapy to demonstrate the sensitivity of optics to physiological perturbations within one week of treatment. Thus, these studies provide critical information regarding the spectral content of DOI necessary for clinical applications, such as early cancer detection, distinguishing between malignant and benign tumors, and monitoring the effects of neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Materials and methods

Broadband DOS measurements were made with the laser breast scanner (Fig. 1a). The laser breast scanner is a bedside-capable system that combines frequency-domain photon migration with steady-state tissue spectroscopy to measure complete (broadband) NIR absorption and reduced scattering spectra of breast tissue in vivo. Detailed descriptions of the instrumentation and theory have been provided elsewhere [34–36].

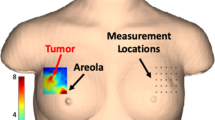

DOS measurements are made by placing the hand-held probe (Fig. 1b) on the tissue surface and moving the probe to discrete locations along a line at 1.0 cm intervals. This forms a linescan across the lesion and surrounding normal tissue (Fig. 2a). The number of DOS positions varies depending on the lesion size. For comparison, a linescan is also performed at an identical location on the contralateral breast. Two measurements are made in each location and all measurement positions are marked on the skin with a surgical pen. The average laser optical power launched into the tissue is about 10 to 20 mW and the total measurement time to generate complete NIR absorption and scattering spectra from a single position is typically about 30 seconds. A complete DOS study including calibration time is approximately 30 to 45 minutes.

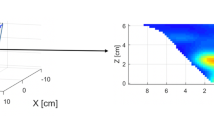

Geometry of the diffuse optical spectroscopy linescan, demonstrating (a) measurement locations and (b) overall probe orientation on the breast. The handheld probe was moved along a linear grid of steps spaced 10 mm apart. Both the tumor region (which had been previously identified) as well as the contra-lateral normal side were measured. Note that the orientation, location, and number of points of the linescan varied with the clinical presentation of the lesion. In (b) we demonstrate the diffusive nature of near infrared photons in tissue.

The probe source and detector separation is 28 mm, from which we estimate a mean penetration depth of approximately 10 mm in the tissue. The actual tissue volume interrogated, which is determined by multiple light scattering and absorption (Fig. 2b), extends above and below the mean penetration depth and is estimated to approximately 10 cm3.

Laser breast scanner measurements produce complete absorption and reduced scattering spectra across the NIR (650 to 1,000 nm) at each probe position. From the absorption spectrum, quantitative tissue concentration measurements of oxygenated hemoglobin (ctO2Hb), deoxygenated hemoglobin (ctHHb), water (ctH2O), and lipid are calculated [8]. From these parameters total tissue hemoglobin concentration (ctTHb = ctO2Hb + ctHHb) and tissue hemoglobin oxygenation saturation (stO2 = ctO2Hb/ctTHb × 100%) are calculated. A tissue optical index (TOI) was developed as a contrast function by combining DOS measurements; TOI = ctHHb × ctH2O/(%lipid). The parameters of this contrast function were determined from an evaluation of DOS measurements in a larger population of 58 malignant breast lesions [37]. Spatial variations in TOI allow us to rapidly locate the maximum lesion optical contrast. Tissue scattering is reported by the results of a power law fit of the form scattering = Aλ-SP, where λ is the optical wavelength and SP is scatter power [38, 39]. Data were analyzed with custom software developed in Matlab (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA).

Results and discussion

Tumor properties in pre-menopausal subjects

To determine the sensitivity of optics to breast cancer in younger women, a series of broadband DOS measurements were performed prior to surgical biopsy on 12 patients (13 malignant breast tumors) whose average age was 35.3 ± 3.6 years, with a range of 30 to 39 years. The average body-mass index was 24.5 ± 4.3, with a range of 20.1 to 32.6. The linescan location (Fig. 2) was chosen based upon a priori knowledge of the tumor location from palpation, ultrasound, or X-ray mammography; thus, the intent of this data was not to screen for suspicious lesions but to characterize malignant lesion optical properties. Linescans were performed with 10 mm steps and a source-detector separation of 28 mm. Measurements were repeated twice to evaluate placement errors at each location on the grid. The average tumor size was 35 ± 27 mm, with a range of 9 to 110 mm, and the average Bloom-Richardson score was 6.4 ± 1.4, with a range of 4 to 9. All tumor classifications were determined by standard clinical pathology.

Figure 3 shows average spectra from 12 subjects for normal breast and peak tumor measurements. Clear differences in shape and amplitude of spectral features are visible throughout the 650 to 1,000 nm region. The error bars for each spectrum represent the standard error of the mean for each of the populations (13 spectra from 12 patients). Spectra obtained from each tumor measurement were used to calculate physiological properties, summarized in Table 1. We performed non-parametric standard tests for significance for these values (Wilcoxon Ranked-sum test, two-sided, 95% confidence). The results of the analysis show that the basis chromophores, ctHHb, ctO2Hb, ctH2O, %lipid, and scatter power (or the exponent of the scattering spectrum power law) all display statistically significant differences between normal and tumor tissue. Mean tumor levels of ctHHb, ctO2Hb, and ctH2O are nearly two-fold greater than normal; tumor %lipid is reduced by approximately 45%, and scatter power increases by about 40% in tumors. Table 2 summarizes the contrast between tumor and normal tissue for the calculated indices ctTHb, stO2, and TOI as defined above. Mean ctTHb, an index of angiogenesis, is approximately two-fold greater for tumors versus normal tissue. TOI, a composite contrast index that reflects both cellular and stromal components, shows a nearly 10-fold contrast between tumors and normal tissue, although with high variability. Both ctTHb and TOI are significantly greater for tumors versus normal tissue, while stO2, an index of tissue oxygen consumption, is, on average, slightly lower in tumors but not significantly different from normal tissue. We note that stO2 does not appear to be a good index for discriminating between malignant and normal tissues in this patient population (ages 30 to 39 years).

Averaged absorption spectra from 13 tumors in 12 patients aged from 30 to 39 years. The tumor spectra clearly demonstrate different spectral features from the normal tissue. The increased absorption in the 650 to 850 nm region is indicative of increased oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin concentration. The increased absorption in the 950 to 1,000 nm region is indicative of increased tissue water concentration. Normal tissue lipid contrast is evident in the 900 to 950 nm region (Tables 1 and 2). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean for the given population, shown every 20 nm.

Tumor tissue displays increased absorption in the 650 to 850 nm spectral range, corresponding to elevated ctTHb. Additional contrast features appear from 900 to 1,000 nm due to variations in water and lipid composition. High ctTHb corresponds to elevated tissue blood volume fraction and angiogenesis; high ctH2O suggests edema and increased cellularity; decreased lipid content reflects displacement of parenchymal adipose, and decreased stO2 indicates tissue hypoxia driven by metabolically active tumor cells. Tumor tissue can also have higher scattering values and a larger scatter power than normal tissue. The physiological interpretation of this observation is that tumors are composed of smaller scattering particles, most likely due to their high epithelial and collagen content, compared to surrounding normal tissue. These changes can be grouped together to enhance contrast through the formation of the TOI, where elevated TOI values suggest high metabolic activity and malignancy [40]. We are currently exploring the development of additional TOI functions that can be derived from base parameters in order to optimize measurement sensitivity to factors such as cellular metabolism, extracellular matrix, and angiogenesis.

Monitoring neoadjuvant chemotherapy

Figure 4a shows a TOI linescan obtained from the right breast of a 48 year old pre-menopausal patient with a 4.0 by 2.5 by 2.5 cm invasive ductal carcinoma (determined by MRI). The TOI peak contrast is approximately three-fold greater for the tumor versus normal tissue. The tumor spatial extent mapped by the DOS linescan is in good agreement with MRI data. The error bars represent the standard deviation of the measurement from successive averaged linescans.

Response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy observed by diffuse optical spectroscopy (DOS). (a) DOS linescan of the tumor using the combined tissue optical index (TOI) shows a clear maximum in the region of the tumor (TOI = ctHHb × ctH2O/%lipid). (b) Changes in the TOI observed post-therapy. Time point 0 was taken just prior to treatment. Note that changes are observed in the TOI of the tumor (triangles) in as little as one day post-therapy. The dynamics of these early changes may be useful in assessing functional response to a given neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimen. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the measurement.

Figure 4b shows the time-dependent TOI response following a single dose of adriamycin and cyclophosphamide neoadjuvant chemotherapy. TOI values in Fig. 4b were determined by averaging the three peak levels in each linescan (positions 4, 5, 6) with error bars as for Fig. 4a. Measurements prior to and on days 1, 2, 3, 6 and 8 following therapy are shown. Note the dramatic drop in TOI from 2.5 prior to therapy to 1.7, a 30% drop in only 1 day. By day 8, peak TOI levels (1.0) were approximately equal to normal baseline (0.8), representing a 60% reduction in 1 week. These results are due to a 30% reduction in ctTHb and ctH2O, and a 20% increase in lipid at the tumor. They are comparable to our previous report of 20% to 30% changes in ctTHb, ctH2O, and %lipid for a neoadjuvant chemotherapy responder during the first week [23]. We are currently expanding our study population in order to capture a sufficient number of non-, partial-, and complete responders (determined by pathology) to evaluate whether these three cases can be distinguished. In this manner, we expect to use DOS to provide rapid, bedside feedback for monitoring and predicting therapeutic response.

Conclusion

Tumor and normal breast tissues displayed significant differences in ctHHb (p = 0.005), ctO2Hb (p = 0.002), ctH2O (p = 0.014), and lipids (p = 0.0003) in a population of 12 women aged from 30 to 39 years. These physiological data were assembled into a TOI to enhance the functional contrast between malignant and normal tissues; however, stO2 was not found to be a reliable index in this regard. A 50% decrease in TOI was measured within 1 week for a patient undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

DOS and DOI are relatively inexpensive technologies that do not require compression, are intrinsically sensitive to the principal components of breast tissue, and are compatible with the use of exogenous molecular probes. DOS is easily integrated into conventional imaging approaches such as MRI, ultrasound, and mammography; and performance is not compromised by structural changes that impact breast density. As a result, diffuse optics may be advantageous for populations with dense breasts, such as younger women, high-risk subjects, and women receiving hormone replacement therapy. Because NIR light is non-ionizing, DOI can be used to monitor physiological changes on a frequent basis without exposing the tissue to potentially harmful radiation. Finally, because DOS can be used to quantitatively assess tumor biochemical composition, it can be applied to monitoring tumor response to therapy. Because these changes occur predominantly early in the course of treatment, we anticipate that diffuse optics will play an important role in minimizing toxicity, predicting responders early in the course of therapy, and developing 'real time' strategies for individualized patient care.

Note

This article is part of a review series on Imaging in breast cancer, edited by David A Mankoff.

Other articles in the series can be found online at http://breast-cancer-research.com/articles/review-series.asp?series=BCR_Imaging

Abbreviations

- ctH2O:

-

water concentration

- ctHHb:

-

deoxygenated hemoglobin concentration

- ctO2Hb:

-

oxygenated hemoglobin concentration

- ctTHb:

-

total tissue hemoglobin concentration

- DOI:

-

diffuse optical imaging

- DOS:

-

diffuse optical spectroscopy

- MRI:

-

magnetic resonance imaging

- NIR:

-

near infrared

- stO2:

-

tissue hemoglobin oxygenation saturation

- TOI:

-

tissue optical index.

References

Kerlikowske K, Grady D, Barclay J, Sickles EA, Ernster V: Likelihood ratios for modern screening mammography. Risk of breast cancer based on age and mammographic interpretation. J Am Med Assoc. 1996, 276: 39-43. 10.1001/jama.276.1.39.

Hindle WH, Davis L, Wright D: Clinical value of mammography for symptomatic women 35 years of age and younger. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999, 180: 1484-1490. 10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70043-8.

White E, Velentgas P, Mandelson MT, Lehman CD, Elmore JG, Porter P, Yasui Y, Taplin SH: Variation in mammographic breast density by time in menstrual cycle among women aged 40–49 years. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998, 90: 906-910. 10.1093/jnci/90.12.906.

Baines CJ, Dayan R: A tangled web: factors likely to affect the efficacy of screening mammography. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999, 91: 833-838. 10.1093/jnci/91.10.833.

Laya MB, Larson EB, Taplin SH, White E: Effect of estrogen replacement therapy on the specificity and sensitivity of screening mammography. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996, 88: 643-649.

Litherland JC, Stallard S, Hole D, Cordiner C: The effect of hormone replacement therapy on the sensitivity of screening mammograms. Clin Radiol. 1999, 54: 285-288. 10.1016/S0009-9260(99)90555-X.

Cancer Facts and Figures 2004. [http://www.cancer.org/docroot/STT/content/STT_1x_Cancer_Facts__Figures_2004.asp]

Cerussi AE, Jakubowski D, Shah N, Bevilacqua F, Lanning R, Berger AJ, Hsiang D, Butler J, Holcombe RF, Tromberg BJ: Spectroscopy enhances the information content of optical mammography. J Biomed Opt. 2002, 7: 60-71. 10.1117/1.1427050.

Shah N, Cerussi A, Eker C, Espinoza J, Butler J, Fishkin J, Hornung R, Tromberg B: Noninvasive functional optical spectroscopy of human breast tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001, 98: 4420-4425. 10.1073/pnas.071511098.

Cubeddu R, D'Andrea C, Pifferi A, Taroni P, Torricelli A, Valentini G: Effects of the menstrual cycle on the red and near-infrared optical properties of the human breast. Photochem Photobiol. 2000, 72: 383-391. 10.1562/0031-8655(2000)072<0383:EOTMCO>2.0.CO;2.

Simick MK, Jong R, Wilson B, Lilge L: Non-ionizing near-infrared radiation transillumination spectroscopy for breast tissue density and assessment of breast cancer risk. J Biomed Opt. 2004, 9: 794-803. 10.1117/1.1758269.

Durduran T, Choe R, Culver JP, Zubkov L, Holboke MJ, Giammarco J, Chance B, Yodh AG: Bulk optical properties of healthy female breast tissue. Phys Med Biol. 2002, 47: 2847-2861. 10.1088/0031-9155/47/16/302.

Pogue BW, Jiang S, Dehghani H, Kogel C, Soho S, Srinivasan S, Song X, Tosteson TD, Poplack SP, Paulsen KD: Characterization of hemoglobin, water, and NIR scattering in breast tissue: analysis of intersubject variability and menstrual cycle changes. J Biomed Opt. 2004, 9: 541-552. 10.1117/1.1691028.

Fantini S, Walker SA, Franceschini MA, Kaschke M, Schlag PM, Moesta KT: Assessment of the size, position, and optical properties of breast tumors in vivo by noninvasive optical methods. Appl Opt (USA). 1998, 37: 1982-1989.

Franceschini MA, Moesta KT, Fantini S, Gaida G, Gratton E, Jess H, Mantulin WW, Seeber M, Schlag PM, Kaschke M: Frequency-domain techniques enhance optical mammography: initial clinical results. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997, 94: 6468-6473. 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6468.

Tromberg BJ, Coquoz O, Fishkin JB, Phan T, Anderson ER, Butler J, Cahn M, Gross JD, Venugopalan V, Pham D: Non-invasive measurements of breast tissue optical properties using frequency-domain photon migration. Phil Trans Royal Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1997, 352: 661-668. 10.1098/rstb.1997.0047.

Tromberg BJ, Shah N, Lanning R, Cerussi A, Espinoza J, Pham T, Svaasand L, Butler J: Non-invasive in vivo characterization of breast tumors using photon migration spectroscopy. Neoplasia. 2000, 2: 26-40. 10.1038/sj.neo.7900082.

Ntziachristos V, Yodh AG, Schnall M, Chance B: Concurrent MRI and diffuse optical tomography of breast after indocyanine green enhancement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000, 97: 2767-2772. 10.1073/pnas.040570597.

Pogue BW, Poplack SP, McBride TO, Wells WA, Osterman KS, Osterberg UL, Paulsen KD: Quantitative hemoglobin tomography with diffuse near-infrared spectroscopy: pilot results in the breast. Radiology. 2001, 218: 261-266.

Zhu Q, Huang M, Chen N, Zarfos K, Jagjivan B, Kane M, Hedge P, Kurtzman SH: Ultrasound-guided optical tomographic imaging of malignant and benign breast lesions: initial clinical results of 19 cases. Neoplasia. 2003, 5: 379-388.

Taroni P, Danesini G, Torricelli A, Pifferi A, Spinelli L, Cubeddu R: Clinical trial of time-resolved scanning optical mammography at 4 wavelengths between 683 and 975 nm. J Biomed Opt. 2004, 9: 464-473. 10.1117/1.1695561.

Yates T, Hebden JC, Gibson A, Everdell N, Arridge SR, Douek M: Optical tomography of the breast using a multi-channel time-resolved imager. Phys Med Biol. 2005, 50: 2503-2517. 10.1088/0031-9155/50/11/005.

Jakubowski DB, Cerussi AE, Bevilacqua F, Shah N, Hsiang D, Butler J, Tromberg BJ: Monitoring neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer using quantitative diffuse optical spectroscopy: a case study. J Biomed Opt. 2004, 9: 230-238. 10.1117/1.1629681.

Shah N, Gibbs J, Wolverton D, Cerussi A, Hylton N, Tromberg B: Combined diffuse optical spectroscopy and contrast-enhanced MRI for monitoring breast cancer neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a case study. J Biomed Opt

Zhu Q, Kurtzma SH, Hegde P, Tannenbaum S, Kane M, Huang M, Chen NG, Jagjivan B, Zarfos K: Utilizing optical tomography with ultrasound localization to image heterogeneous hemoglobin distribution in large breast cancers. Neoplasia. 2005, 7: 263-270.

Patterson MS, Chance B, Wilson BC: Time resolved reflectance and transmittance for the non-invasive measurement of tissue optical properties. Appl Opt. 1989, 28: 2331-2336.

Patterson MS, Moulton JD, Wilson BC, Berndt KW, Lakowicz JR: Frequency-domain reflectance for the determination of the scattering and absorption properties of tissue. Appl Opt. 1991, 30: 4474-4476.

Tromberg BJ, Svaasand LO, Tsong-Tseh T, Haskell RC: Properties of photon density waves in multiple-scattering media. Appl Opt. 1993, 32: 607-616.

Fishkin JB, Gratton E: Propagation of photon-density waves in strongly scattering media containing an absorbing semi-infinite plane bounded by a straight edge. J Opt Soc Am A. 1993, 10: 127-140.

Wilson BC, Patterson MS, Flock ST, Wyman DR: Tissue optical properties in relation to light propagation models and in vivo dosimetry. Photon Migration in Tissues. Edited by: Chance B. 1988, New York: Plenum, 25-42.

Hebden JC, Arridge SR, Delpy DT: Optical imaging in medicine. I. Experimental techniques. Phys Med Biol. 1997, 42: 825-840. 10.1088/0031-9155/42/5/007.

Gibson AP, Hebden JC, Arridge SR: Recent advances in diffuse optical imaging. Phys Med Biol. 2005, 50: R1-43. 10.1088/0031-9155/50/4/R01.

Quaresima V, Matcher SJ, Ferrari M: Identification and quantification of intrinsic optical contrast for near-infrared mammography. Photochem Photobiol. 1998, 67: 4-14. 10.1562/0031-8655(1998)067<0004:IAQOIO>2.3.CO;2.

Pham TH, Coquoz O, Fishkin JB, Anderson E, Tromberg BJ: Broad bandwidth frequency domain instrument for quantitative tissue optical spectroscopy. Rev Sci Instrum. 2000, 71: 2500-2513. 10.1063/1.1150665.

Bevilacqua F, Berger AJ, Cerussi AE, Jakubowski D, Tromberg BJ: Broadband absorption spectroscopy in turbid media by combined frequency-domain and steady-state methods. Appl Opt. 2000, 39: 6498-6507.

Jakubowski D: Development of broadband quantitative tissue optical spectroscopy for the non-invasive characterization of breast disease. PhD thesis. 2002, Irvine: Beckman Laser Institute and Department of Physics, University of California

Cerussi A, Shah N, Hsiang D, Compton M, Tromberg B: In vivo absorption, scattering and physiologic properties of 58 malignant breast tumors determined by broadband diffuse optical spectroscopy. J Biomed Opt

Mourant JR, Fuselier T, Boyer J, Johnson TM, Bigio IJ: Predictions and measurements of scattering and absorption over broad wavelength ranges in tissue phantoms. Appl Opt. 1997, 36: 949-957.

Nilsson AMK, Sturesson C, Liu DL, Andersson-Engels S: Changes in spectral shape of tissue optical properties in conjunction with laser-induced thermotherapy. Appl Opt. 1998, 37: 1256-1267.

Shah N, Cerussi AE, Jakubowski D, Hsiang D, Butler J, Tromberg BJ: The role of diffuse optical spectroscopy in the clinical management of breast cancer. Dis Markers. 2003, 19: 95-105.

Acknowledgements

This work was made possible by the NIH NCRR biomedical technology center, the Laser Microbeam and Medical Program (LAMMP, P41RR01192), the California Breast Cancer Research Program, and the NCI network for translational research in optical imaging (U54CA105480). Beckman Laser Institute programmatic support is provided by the AFOSR and the Beckman Foundation. Use of Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center facilities at UCI (NCI P30 CA62203) is gratefully acknowledged. Finally, the authors wish to thank the patients who generously volunteered for these studies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tromberg, B.J., Cerussi, A., Shah, N. et al. Imaging in breast cancer: Diffuse optics in breast cancer: detecting tumors in pre-menopausal women and monitoring neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res 7, 279 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr1358

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr1358