Abstract

Women with mutations in the breast cancer susceptibility genes, BRCA1 and BRCA2, have an increased risk of developing breast cancer. Both BRCA1 and BRCA2 are thought to be tumour suppressor genes since the wild type alleles of these genes are lost in tumours from heterozygous carriers. Several functions have been proposed for the proteins encoded by these genes which could explain their roles in tumour suppression. Both BRCA1 and BRCA2 have been suggested to have a role in transcriptional regulation and several potential BRCA1 target genes have been identified. The nature of these genes suggests that loss of BRCA1 could lead to inappropriate proliferation, consistent with the high mitotic grade of BRCA1-associated tumours. BRCA1 and BRCA2 have also been implicated in DNA repair and regulation of centrosome number. Loss of either of these functions would be expected to lead to chromosomal instability, which is observed in BRCA1 and BRCA2-associated tumours. Taken together, these studies give an insight into the pathogenesis of BRCA-associated tumours and will inform future therapeutic strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

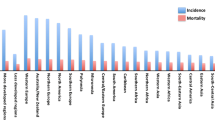

About one in 12 women in the Western world develop cancer of the breast, and at least 5% of these cases are thought to result from a hereditary predisposition to the disease [1,2]. Two breast cancer susceptibility genes in humans (BRCA1 and BRCA2) have been mapped and cloned, and mutations in these genes account for most families with four or more cases of breast cancer diagnosed before the age of 60 years. (Note that 'Brca1' and 'Brca2' are used in the following discussion to denote the equivalent genes in mice, and that Roman text indicates the encoded protein.) Women who inherit loss-of-function mutations in either of these genes have approximately 85% risk of developing breast cancer by age 70 years [3]. Both BRCA1 and BRCA2 are thought to be tumour-suppressor genes, because the wild-type allele of the gene is observed to be lost in tumours of heterozygous carriers. As well as breast cancer, carriers of mutations in these genes are at elevated risk of cancer of the ovary, prostate and pancreas. Surprisingly, however, despite the association with inherited predisposition, somatic disease-causing mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 are extremely rare in sporadic breast cancers [1,2].

The BRCA1 gene is made up of 22 coding exons and encodes a protein of 1863 amino acids [4**]. Most of the coding region shows no sequence similarity to previously described proteins, apart from the presence of a RING zinc finger domain at the N-terminus of the protein and two 'BRCT' repeats at the C-terminus [2] (Fig. 1). The BRCA2 gene has 26 coding exons and encodes a protein of 3418 amino acids, with an estimated molecular weight of 384 kDa [2,5**]. The only obvious feature of the BRCA2 protein is the presence of eight copies of a 30-80 amino acid repeat (the BRC repeat) in the part of the protein encoded by exon 11 [6*,7*] (Fig. 1). These repeats are able to bind the RAD51 protein implicated in DNA repair and recombination [8*,9*].

Functions for the BRCA proteins in both transcriptional regulation and DNA repair/recombination have been suggested [2]. It is still unclear, however, how loss of BRCA gene function leads to tumourigenesis. Important clues to this process are provided by the pathological features of breast tumours in women who are carriers for mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2. These tumours are clearly distinct from each other, as well as from sporadic tumours [10**]. This indicates that, despite many similarities in these genes [2], they must have at least some nonredundant functions. The evidence for the proposed functions of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins are reviewed and related to some of the pathological features of BRCA-associated tumours.

Transcriptional regulation

The presence in BRCA1 of a RING finger domain, which are frequently found in transcriptional regulatory proteins, led to the tacit assumption that BRCA1 might be involved in the transcriptional regulation of genes [4**]. Subsequently, however, it has become clear that RING finger domains are found in a wide variety of proteins of different function, and are indicative of protein-protein interaction rather than interaction with DNA. Nevertheless, there is significant accumulating evidence for a role in transcriptional regulation for BRCA1, and to a lesser extent for BRCA2. Disregulation of target genes consequent to the loss of BRCA genes is a plausible mechanism to explain the pathological features of BRCA-associated tumours. As described below, however, the exact function of the BRCA proteins in transcriptional regulation is not yet understood.

A C-terminal fragment of BRCA1, which is fused to the GAL4 DNA-binding domain, activates transcription of reporter genes, suggesting that BRCA1 might regulate transcriptional activation [11*,12*,13*]. The finding that endogenous, full-length BRCA1 copurifies with the RNA Pol II holoenzyme complex via an interaction with RNA helicase A supports such a role for BRCA1 [14*,15,16]. It is worth noting, however, that RAD51 can also be found in this complex despite having no known role in transcriptional regulation [17].

Several groups have used overexpression of BRCA1 in various cell lines to find targets of BRCA1 transcriptional regulation (Table 1). Most work has concentrated on the cell division kinase (CDK) inhibitor, p21WAF1, which acts to arrest the cell cycle at the G1 to S phase and G2 to M phase transitions [18]. In COS cells, 293T cells and human colon cancer cells, reporter constructs containing portions of the p21 WAF1promoter are activated by overexpression of BRCA1 [19*,20,21,22]. Furthermore, in colon cancer cells, BRCA1 overexpression leads to an increase in p21WAF1 protein levels, accompanied by cell cycle arrest [19*]. There may be some cell-type specificity in this, however, because overexpression of BRCA1 in osteosarcoma cells does not induce increased p21WAF1 protein levels [23*]. Other studies suggest that BRCA1 may also be able to activate the promoters of the proapoptotic gene BAX, the G2 to M phase checkpoint gene GADD45, and the p53 regulatory gene MDM2 [20,21,23*].

There are also some indications that BRCA1 may act as a repressor of transcription. BRCA1 overexpression has been shown to inhibit transcription from the promoter of the cell-cycle regulatory gene CDC25A and from a synthetic oestrogen receptor-responsive promoter [24,25*]. This may involve the interaction of BRCA1, via CtIP, with the transcriptional corepressor CtBP [26*,27*]. CtBP can inhibit transcription by binding the histone deactylase HDAC1, which has been found in BRCA1-containing complexes [28*]. When BRCA1 alone is overexpressed in 293 cells, a p21 WAF1 promoter-reporter construct is activated, but when CtIP and CtBP are coexpressed it is not [27*]. Interestingly, interaction of BRCA1 with CtIP and CtBP is disrupted upon DNA damage, suggesting a role for BRCA1 in the DNA damage-dependent induction of p21WAF1 [27*]. Because loss of Brca1 in mouse embryos also leads to induction of p21WAF1 [29**], however, the role of BRCA1 in p21WAF1 regulation is not clear.

There are, as yet, no reports of BRCA1 binding DNA and acting directly as a transcription factor. Rather, BRCA1 appears to exert its influence on transcription as a cofactor or adaptor, because it can interact with both DNA-binding transcription factors and the RNA Pol II holoenzyme. The influence of BRCA1 on the p21 WAF1, BAX and MDM2 promoters is mediated, at least in part, by p53, with which BRCA1 has been shown to physically interact [20,21,22].

Transcriptional regulation has also been proposed as a function of BRCA2, because sequences encoded by exon three, when fused to the GAL4 DNA-binding domain, can activate transcription of a reporter gene [30*]. It is not clear whether these sequences can function similarly in the context of the intact protein, however. Other evidence supporting a role for BRCA2 in transcriptional regulation is that it can associate with histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity. The exact nature of this association is not clear, because one study suggested that BRCA2 has intrinsic HAT activity [31*], whereas another suggested that it is associated with HAT activity by virtue of an interaction with P/CAF, which possesses HAT activity [32*]. Association with HAT activity does not necessarily denote a role in transcriptional regulation, however. It could also reflect a role in chromatin remodelling, which might be required for the proposed role of BRCA2 in homologous recombination, which is discussed below.

The promoters that BRCA1 has been shown to activate are those for stress-induced genes involved in cell cycle checkpoints, whereas those that BRCA1 inhibits are for cell division promoting genes. This is consistent with BRCA1 regulating checkpoints and cell proliferation. Particularly interesting in this context is the report that over-expression of BRCA1 can inhibit oestrogen receptor signalling [25*]. This suggests a model whereby loss of BRCA1 could lead to an increased proliferative capacity of the breast epithelium in response to oestrogen. However, this appears to be at odds with clinical findings that show loss of the oestrogen receptor in a high proportion of BRCA-associated breast tumours [33,34].

A major problem with many of the studies described above is that overexpression of BRCA1 itself, especially at inappropriate phases of the cell cycle, could cause genotoxic stress and thus lead to expression of stress-induced genes as a secondary effect. Experiments using BRCA-null cells in which exogenous BRCA expression is induced to wild-type levels at the appropriate time in the cell cycle would rule out this possibility.

DNA repair

Mouse cells with Brca1 or Brca2 mutations are hypersensitive to ionizing radiation, a genotoxic treatment that causes primarily double-strand breaks in DNA [35**,36**,37**,38**]. This suggests that Brca1 and Brca2 play a part in the cellular response to DNA double-strand breaks. This function may be restricted to part of the cell cycle, however, because Brca2 mutant cells can repair the double-strand breaks that arise during V(D)J recombination [38**] (Bertwistle D, Ashworth A, unpublished observations); these occur during the G1 phase of the cell cycle, when nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) is thought to repair most double-strand breaks [39]. Expression of BRCA1 and BRCA2 is very low during G1phase, but is induced as cells enter S phase [40*,41*]. During the late S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, when there are two copies of chromosomes, one copy can be used as a template to repair double-strand breaks in the other by homologous recombination [39]. In dividing mammalian cells as many as 30-50% of DNA double-strand breaks may be repaired this way [42]. RAD51, a protein that plays a key role in homologous recombination, has been shown to associate with both BRCA1 and BRCA2 [8*,9*,35**,43,44**]. Furthermore, BRCA1 also associates with the RAD50-MRE11-nibrin complex, which is thought to process DNA double-strand breaks for repair by both NHEJ and homologous recombination [45**]. Together, these data suggest that BRCA1 and BRCA2 are involved in homologous recombination-mediated repair of DNA double-strand breaks. To complicate matters, however, there is also some evidence that BRCA1 may have a role in the mechanistically independent process of the transcription-coupled repair of oxidative DNA damage [46].

Spontaneous chromosomal abnormalities are observed at high frequency in untreated Brca1 and Brca2 mutant cells, implying that these genes act to repair DNA damage that occurs as a consequence of normal cell division, as well as that caused by genotoxic agents [36**,38**]. The nature of the chromosomal aberrations suggests a defect in the repair of DNA damage sustained during the S or G2 phase of the cell cycle. Because BRCA1 and BRCA2 are associated with RAD51, it is significant that loss of RAD51 causes chicken DT40 cells to spontaneously accumulate DNA double-strand breaks, arrest at the G2/M phase transition and die [47]. A possible explanation for such severe phenotypes comes from studies in bacteria, which suggest that double-strand breaks occur frequently as a normal consequence of DNA replication and are repaired by homologous recombination [48]. The role of homologous recombination in DNA replication in eukaryotes is less clear. Holliday junction recombination intermediates do spontaneously arise in normal yeast cells during S phase, however [49]. This suggests that homologous recombination repairs DNA damage that occurs spontaneously during DNA replication in eukaryotic as well as in prokaryotic cells. The embryonic lethality observed in Rad51 null mice [50] and many Brca1 and Brca2 mutant mouse strains may therefore be due to a failure of DNA replication.

Cell cycle checkpoint activation and loss

Cells respond to DNA damage by activating checkpoints that prevent their progression through the cell cycle. The spontaneous DNA damage observed in Brca1 and Brca2 mutant cells would be predicted to activate such checkpoints. Indeed, these cells suffer from a proliferative defect, probably due to checkpoint activation caused by upregulation of the CDK inhibitor p21WAF1 [29**,37**,38**]. p21WAF1 is induced in response to DNA damage by p53, which is upregulated in Brca2 mutant cells. Therefore, loss of the p53 pathway would be predicted to alleviate the proliferation defect observed in Brca1 and Brca2 mutant cells. Although this may be the case for some mutations [51**], others are only partially rescued [52**] (Connor F, Ashworth A, unpublished observation), suggesting that this is not the only checkpoint that is activated. Nevertheless, loss of the p53 pathway appears to be important for the progression of BRCA-associated tumours. Supporting this hypothesis is the finding that p53 mutations are found at a higher frequency in BRCA-associated breast tumours than in sporadic breast tumours [53,54**].

Checkpoints exist at G1/S, S, G2/M and M in the cell cycle, and all these appear to be operational in Brca2 mutant cells [38**,51**]. In contrast, cells in which exon 11 of Brca1 is deleted have an intact G1/S checkpoint, but are defective in an ionizing radiation-induced G2/M checkpoint [55**]. Furthermore, cells overexpressing a C-terminal fragment of BRCA1 fail to arrest when treated with the spindle inhibitor colchicine [56]. These results suggest that BRCA1 may also be involved in the G2/M and spindle checkpoints.

The spindle checkpoint acts to monitor the fidelity of chromosome segregation during mitosis [57]. Chromosome segregation is controlled by the mitotic spindle, a system of microtubules organized by the centrosome. During mitosis, there are two centrosomes, one at either end of the mitotic spindle, and one diploid set of chromosomes segregates to each. The spindle checkpoint prevents chromosome missegregation by ensuring that each chromosome pair has recruited microtubules from both poles of a bipolar spindle, before chromosome segregation occurs at anaphase.

At the end of mitosis each daughter cell inherits one of the two centrosomes, and duplicates this at the G1/S phase transition so that it has two centrosomes during mitosis [58]. Recent studies have found that a high proportion of Brca1 and Brca2 mutant cells contain supernumerary centrosomes [55**,59**]. There is thought to be no checkpoint monitoring the number of centrosomes in a cell, and therefore cells with excess centrosomes can enter mitosis [60]. Some of these cells might be predicted to arrest during mitosis due to the activation of the spindle checkpoint, however. Indeed, the growth of Brca2 mutant cells can be rescued by the expression of a dominant negative mutant of the spindle checkpoint gene BUB1 [51**]. This implies that some Brca2 mutant cells activate the spindle checkpoint.

Under certain circumstances, however, mitoses with supernumerary centrosomes can fail to activate the spindle checkpoint [60] and this could lead to chromosome missegregation [61]. The consequence of this would be chromosome gain or loss and therefore aneuploidy, which is observed in a large proportion of Brca1 and Brca2 mutant cells [55**,59**]. These results suggest that Brca1 and Brca2 may regulate centrosome duplication. The finding that BRCA1 associates with centrosomal proteins supports this hypothesis [62]. Alternatively, the excess of centrosomes in Brca1 and Brca2 mutant cells may be a secondary effect; centrosomes can undergo multiple rounds of duplication during S-phase arrest leading to supernumerary centrosomes [60,63]. Whatever the mechanism of centrosome amplification in Brca1 and Brca2 mutant cells, this phenomenon suggests that mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 might cause chromosomal instability in human tumours. It will be interesting to know whether these tumours have a high frequency of mutations in spindle checkpoint genes.

The chromosomal aberrations and aneuploidy found in mouse cells mutant for Brca1 or Brca2 are in agreement with the pathological data showing chromosomal instability in BRCA-associated breast tumours [64*]. In the light of these profound and irreversible changes, therapeutic strategies involving the reintroduction of BRCA1 or BRCA2 into tumours [65] may well be viewed as closing the stable door after the horse has bolted.

Conclusion

Our understanding of the precise functions of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins and how their loss leads to tumourigenesis is still incomplete. However, we now have several clues as to the general cellular processes in which these proteins are involved, and this understanding has already illuminated some of the pathological features of BRCA-associated breast tumours. Activation or repression of transcriptional targets of the BRCA1 protein might play a role in tumour initiation or progression. These changes in gene expression may underpin some of the pathological changes associated with the tumours. Lack of activation of stress-induced checkpoint genes could contribute to aneuploidy. Failure to inhibit growth promoting genes could increase and disregulate proliferation. The genetic instability observed in mouse models and human tumours most likely reflects a role for BRCA1 and BRCA2 in homologous recombination and possibly in centrosome regulation. This effect may manifest itself relatively early in breast cancer progression, increasing the probability of tumourigenesis rather than directly promoting tumour growth. The synergy between mutations in p53 and the BRCA genes in tumours indicates a role for loss of checkpoint control in tumour progression. Taken together these findings give an insight into the pathogenesis of BRCA-associated tumours and will inform future therapeutic strategies.

References

Rahman N, Stratton MR: The genetics of breast cancer susceptibility. Annu Rev Genet. 1998, 32: 95-121. 10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.95.

Bertwistle D, Ashworth A: Functions of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998, 8: 14-20. 10.1016/S0959-437X(98)80056-7.

Easton D: Breast cancer genes: what are the real risks? . Nature Genet. 1997, 16: 210-211.

Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D, et al: A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science. 1994, 266: 66-71.

Wooster R, Bignell G, Lancaster J, et al: Identification of the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA2. Nature. 1995, 378: 789-791. 10.1038/378789a0.

Bork P, Blomberg N, Nilges M: Internal repeats in the BRCA2 protein sequence. Nature Genet. 1996, 13: 22-23.

Bignell G, Micklem G, Stratton MR, Ashworth A, Wooster R: The BRC repeats are conserved in mammalian BRCA2 proteins. Hum Mol Genet. 1997, 6: 53-58. 10.1093/hmg/6.1.53.

Chen PL, Chen CF, Chen Y, et al: The BRC repeats in BRCA2 are critical for RAD51 binding and resistance to methyl methanesulfonate treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998, 95: 5287-5292. 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5287.

Wong AKC, Pero R, Ormonde PA, Tavtigian SV, Bartel PL: RAD51 interacts with the evolutionarily conserved BRC motifs in the human breast cancer susceptibility gene BRC. J Biol Chem. 1997, 272: 31941-31944. 10.1074/jbc.272.51.31941.

,: Pathology of familial breast cancer: differences between breast cancers in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and sporadic cases. Lancet. 1997, 349: 1505-1510. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)10109-4.

Chapman MS, Verma IM: Transcriptional activation by BRCA1. Nature. 1996, 382: 678-679. 10.1038/382678a0.

Monteiro ANA, August A, Hanafusa H: Evidence for a transcriptional activation function of BRCA1 C-terminal region. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996, 93: 13595-13599. 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13595.

Haile DT, Parvin JD: Activation of transcription in vitro by the BRCA1 carboxyl-terminal domain. J Biol Chem. 1999, 274: 2113-2117. 10.1074/jbc.274.4.2113.

Scully R, Anderson SF, Chao DM, et al: BRCA1 is a component of the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997, 94: 5605-5610. 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5605.

Anderson SF, Schlegel BP, Nakajima T, Wolpin ES, Parvin JD: BRCA1 protein is linked to the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme complex via RNA helicase A. Nature Genet. 1998, 19: 254-256. 10.1038/930.

Neish AS, Anderson SF, Schlegel BP, Wei W, Parvin JD: Factors associated with the mammalian RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998, 26: 847-853. 10.1093/nar/26.3.847.

Maldonado E, Shiekhattar R, Sheldon M, et al: A human RNA polymerase II complex associated with SRB and DNA-repair proteins. Nature. 1996, 381: 86-89. 10.1038/381086a0.

Niculescu AB, Chen X, Smeets M, et al: Effects of p21(Cip1/Waf1) at both the G1/S and the G2/M cell cycle transitions: pRb is a critical determinant in blocking DNA replication and in preventing endoreduplication. Mol Cell Biol. 1998, 18: 629-643.

Somasundaram K, Zhang H, Zeng YX, et al: Arrest of the cell cycle by the tumour-suppressor BRCA1 requires the CDK-inhibitor p21WAF1. Nature. 1997, 389: 187-190. 10.1038/38291.

Zhang H, Somasundaram K, Peng Y, et al: BRCA1 physically associates with p53 and stimulates its transcriptional activity. Oncogene. 1998, 16: 1713-1721. 10.1038/sj.onc.1201932.

Ouchi T, Monteiro AN, August A, Aaronson SA, Hanafusa H: BRCA1 regulates p53-dependent gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 1998, 95: 2302-2306. 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2302.

Chai YL, Cui J, Shao N, et al: The second BRCT domain of BRCA1 proteins interacts with p53 and stimulates transcription from the p21WAF1/CIP1 promoter. Oncogene. 1999, 18: 263-268. 10.1038/sj.onc.1202323.

Harkin DP, Bean JM, Miklos D, et al: Induction of GADD45 and JNK/SAPK-dependent apoptosis following inducible expression of BRCA1. Cell. 1999, 97: 575-586. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80769-2.

Wang Q, Zhang H, Kajino K, Greene MI: BRCA1 binds c-Myc and inhibits its transcriptional and transforming activity in cells. Oncogene. 1998, 17: 1939-1948. 10.1038/sj.onc.1202403.

Fan S, Wang J, Yuan R, et al: BRCA1 inhibition of estrogen receptor signaling in transfected cells. Science. 1999, 284: 1354-1356. 10.1126/science.284.5418.1354.

Yu X, Wu LC, Bowcock AM, Aronheim A, Baer R: The C-terminal (BRCT) domains of BRCA1 interact in vivo with CtIP, a protein implicated in the CtBP pathway of transcriptional repression. J Biol Chem. 1998, 273: 25388-25392. 10.1074/jbc.273.39.25388.

Li S, Chen PL, Subramanian T, et al: Binding of CtIP to the BRCT repeats of BRCA1 involved in the transcription regulation of p21 is disrupted upon DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 1999, 274: 11334-11338. 10.1074/jbc.274.16.11334.

Yarden RI, Brody LC: BRCA1 interacts with components of the histone deacetylase complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999, 96: 4983-1988. 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4983.

Hakem R, de la Pompa JL, Sirard C, et al: The tumor suppressorgene Brca1 is required for embryonic cellular proliferation in the mouse. Cell. 1996, 85: 1009-1023. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81302-1.

Milner J, Ponder B, Hughes-Davies L, Seltmann M, Kouzarides T: Transcriptional activation functions in BRCA2. Nature . 1997, 386: 772-773. 10.1038/386772a0.

Siddique H, Zou JP, Rao VN, Reddy ES: The BRCA2 is a histoneacetyltransferase. Oncogene. 1998, 16: 2283-2285. 10.1038/sj.onc.1202003.

Fuks F, Milner J, Kouzarides T: BRCA2 associates with acetyltransferase activity when bound to P/CAF. Oncogene. 1998, 17: 2531-2534. 10.1038/sj.onc.1202475.

Robson M, Rajan P, Rosen PP, et al: BRCA-associated breast cancer: absence of a characteristic immunophenotype. Cancer Res. 1998, 58: 1839-1842.

Osin P, Crook T, Powles T, Peto J, Gusterson B: Hormone status of in-situ cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Lancet. 1998, 351: 1487-. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)24020-7.

Sharan SK, Morimatsu M, Albrecht U, et al: Embryonic lethality andradiation hypersensitivity mediated by Rad51 in mice lacking Brca2. Nature. 1997, 386: 804-810. 10.1038/386804a0.

Shen SX, Weaver Z, Xu X, et al: A targeted disruption of the murine Brca1 gene causes gamma-irradiation hypersensitivity and genetic instability. Oncogene. 1998, 17: 3115-3124. 10.1038/sj.onc.1202243.

Connor F, Bertwistle D, Mee PJ, et al: Tumorigenesis and a DNA repair defect in mice with a truncating Brca2 mutation. Nature Genet. 1997, 17: 423-430.

Patel KJ, Vu VP, Lee H, et al: Involvement of Brca2 in DNA repair. Mol Cell. 1998, 1: 347-357.

Takata M, Sasaki MS, Sonoda E, et al: Homologous recombination and non-homologous end-joining pathways of DNA double-strand break repair have overlapping roles in the maintenance of chromosomal integrity in vertebrate cells. EMBO J. 1998, 17: 5497-508. 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5497.

Chen Y, Farmer AA, Chen CF, et al: BRCA1 is a 220-kDa nuclearphosphoprotein that is expressed and phosphorylated in a cell cycle-dependent manner. Cancer Res. 1996, 56: 3168-3172.

Bertwistle D, Swift S, Marston NJ, et al: Nuclear location and cell cycle regulation of the BRCA2 protein. Cancer Res. 1997, 57: 5485-5488.

Liang F, Han M, Romanienko PJ, Jasin M: Homology-directed repair is a major double-strand break repair pathway in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998, 95: 5172-5177. 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5172.

Baumann P, West SC: Role of the human Rad51 protein in homologous recombination and double-strand break repair. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998, 23: 247-251. 10.1016/S0968-0004(98)01232-8.

Scully R, Chen J, Plug A, et al: Association of BRCA1 with Rad51 in mitotic and meiotic cells. Cell. 1997, 88: 265-275.

Zhong Q, Chen CF, Li S, et al: Association of BRCA1 with the hRad50-hMre11-p95 complex and the DNA damage response. Science. 1999, 285: 747-750. 10.1126/science.285.5428.747.

Gowen LC, Avrutskaya AV, Latour AM, Koller BH, Leadon SA: BRCA1 required for transcription-coupled repair of oxidative DNA damage. Science. 1998, 281: 1009-1012. 10.1126/science.281.5379.1009.

Sonoda E, Sasaki MS, Buerstedde JM, et al: Rad51-deficient vertebrate cells accumulate chromosomal breaks prior to cell death. EMBO J. 1998, 17: 598-608. 10.1093/emboj/17.2.598.

Michel B, Ehrlich SD, Uzest M: DNA double-strand breaks caused by replication arrest. EMBO J. 1997, 16: 430-438. 10.1093/emboj/16.2.430.

Zou H, Rothstein R: Holliday junctions accumulate in replication mutants via a RecA homolog-independent mechanism. Cell. 1997, 90: 87-96.

Lim DS, Hasty P: A mutation in mouse Rad51 results in an early embryonic lethal that is suppressed by a mutation in p53. Mol Cell Biol. 1996, 16: 7133-7143.

Lee H, Trainer AH, Friedman LS, et al: Mitotic checkpoint inactivation fosters transformation in cells lacking the breast cancer susceptibility gene, Brca2. Mol Cell. 1999, 4: 1-10. 10.1023/A:1007059806016.

Ludwig T, Chapman DL, Papaioannou VE, Efstratiadis A: Targeted mutations of breast cancer susceptibility gene homologs in mice: lethal phenotypes of Brca1, Brca2, Brca1/Brca2, Brca1/p53 and Brca2/p53 nullizygous embryos. Genes Dev. 1997, 11: 1226-1241.

Crook T, Crossland S, Crompton MR, Osin P, Gusterson BA: p53 mutations in BRCA1-associated familial breast cancer. Lancet. 1997, 350: 638-639.

Crook T, Brooks LA, Crossland S, et al: p53 mutation with frequent novel condons but not a mutator phenotype in BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated breast tumours. Oncogene. 1998, 17: 1681-1689. 10.1038/sj.onc.1202106.

Xu X, Weaver Z, Linke SP, et al: Centrosome amplification and a defective G2-M cell cycle checkpoint induce genetic instability in BRCA1 exon 11 isoform-deficient cells. Mol Cell. 1999, 3: 389-395.

Larson JS, Tonkinson JL, Lai MT: A BRCA1 mutant alters G2-M cell cycle control in human mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 1997, 57: 3351-3355.

Hardwick KG: The spindle checkpoint. Trends Genet . 1998, 14: 1-4. 10.1016/S0168-9525(97)01340-1.

Zimmerman W, Sparks CA, Doxsey SJ: Amorphous no longer: the centrosome comes into focus. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999, 11: 122-128. 10.1016/S0955-0674(99)80015-5.

Tutt A, Gabriel A, Bertwistle D, et al: Absence of BRCA2 causes genome instability by chromosome breakage and loss associated with centrosome amplification. Curr Biol. 1999, 9: 1107-1110. 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80479-5.

Sluder G, Thompson EA, Miller FJ, Hayes J, Rieder CL: The checkpoint control for anaphase onset does not monitor excess numbers of spindle poles or bipolar spindle symmetry. J Cell Sci. 1997, 110: 421-429.

Doxsey S: The centrosome: a tiny organelle with big potential. Nature Genet. 1998, 20: 104-106. 10.1038/2392.

Hsu LC, White RL: BRCA1 is associated with the centrosome during mitosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998, 95: 12983-12988. 10.1073/pnas.95.22.12983.

Hinchcliffe EH, Li C, Thompson EA, Maller JL, Sluder G: Requirement of Cdk2-cyclin E activity for repeated centrosome reproduction in Xenopus egg extracts. Science. 1999, 283: 851-854. 10.1126/science.283.5403.851.

Tirkkonen M, Johannsson O, Agnarsson BA, et al: Distinct somatic genetic changes associated with tumor progression in carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 germ-line mutations. Cancer Res. 1997, 57: 1222-1227.

Holt JT: Breast cancer genes: therapeutic strategies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997, 833: 34-41.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bertwistle, D., Ashworth, A. The pathology of familial breast cancer: The pathology of familial breast cancer How do the functions of BRCA1 and BRCA2 relate to breast tumour pathology?. Breast Cancer Res 1, 41 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr12

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr12