Abstract

Introduction

The largest genetic risk to develop rheumatoid arthritis (RA) arises from a group of alleles of the HLA DRB1 locus ('shared epitope', SE). Over 30 non-HLA single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) predisposing to disease have been identified in Caucasians, but they have never been investigated in West/Central Africa. We previously reported a lower prevalence of the SE in RA patients in Cameroon compared to European patients and aimed in the present study to investigate the contribution of Caucasian non-HLA RA SNPs to disease susceptibility in Black Africans.

Methods

RA cases and controls from Cameroon were genotyped for Caucasian RA susceptibility SNPs using Sequenom MassArray technology. Genotype data were also available for 5024 UK cases and 4281 UK controls and for 119 Yoruba individuals in Ibadan, Nigeria (YRI, HapMap). A Caucasian aggregate genetic-risk score (GRS) was calculated as the sum of the weighted risk-allele counts.

Results

After genotyping quality control procedures were performed, data on 28 Caucasian non-HLA susceptibility SNPs were available in 43 Cameroonian RA cases and 44 controls. The minor allele frequencies (MAF) were tightly correlated between Cameroonian controls and YRI individuals (correlation coefficient 93.8%, p = 1.7E-13), and they were pooled together. There was no correlation between MAF of UK and African controls; 13 markers differed by more than 20%. The MAF for markers at PTPN22, IL2RA, FCGR2A and IL2/IL21 was below 2% in Africans. The GRS showed a strong association with RA in the UK. However, the GRS did not predict RA in Africans (OR = 0.71, 95% CI 0.29 - 1.74, p = 0.456). Random sampling from the UK cohort showed that this difference in association is unlikely to be explained by small sample size or chance, but is statistically significant with p<0.001.

Conclusions

The MAFs of non-HLA Caucasian RA susceptibility SNPs are different between Caucasians and Africans, and several polymorphisms are barely detectable in West/Central Africa. The genetic risk of developing RA conferred by a set of 28 Caucasian susceptibility SNPs is significantly different between the UK and Africa with p<0.001. Taken together, these observations strengthen the hypothesis that the genetic architecture of RA susceptibility is different in different ethnic backgrounds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic and chronic inflammatory disease involving mainly the peripheral joints of hands and feet initially. RA is thought to arise from the combination of both genetic and environmental factors. The largest genetic risk arises from a group of alleles of the HLA-DRB1 gene, collectively referred to as the shared epitope (SE). Candidate-gene studies and genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have identified more than 30 non-HLA genetic loci to date [1]. The majority of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with RA susceptibility have been identified and validated in patients of European ancestry who were seropositive for either anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs) or rheumatoid factor.

Several studies have shown that some validated RA risk alleles contribute to risk in other ethnic groups, in particular of Asian ancestry [2–4], and concluded that some RA susceptibility loci show population-specific associations but that others overlap between Asian and European populations.

Ethnic differences in allele frequencies of autoimmune disease-associated SNPs have been clearly shown [5], and a lack of association of a particular SNP in a population may be more likely to represent a lack of power due to low allele frequency than to represent a true negative effect at the individual level. The PTPN22 polymorphism rs2476601, a cardinal example, has an allele frequency of above 10% in healthy individuals of Northern Europe, 3% in Southern European countries, and 2% in Northern African and African-American populations but is absent in Asian populations [6]. However, most common SNPs associated with RA in persons of European ancestry confer risk of RA in African-Americans, whereas discordant genetic loci appear to be the minority [7, 8]. Interestingly, the SE is associated with susceptibility to RA in African-Americans through European genetic admixture [9], and this is likely to be the case for several SNPs outside the HLA-region. African-Americans and Africans, therefore, have to be considered separately for epidemiologic and genetic studies.

Epidemiologic and genetic data on RA in African populations are scarce. RA genetics has been studied mainly in underpowered candidate gene association studies in Northern and Southern Africa, and there have been few reports in Tunisia (PTPN22 [10, 11], TNFAIP3 [12], STAT4 [13], IRF5 [14], DNASE1 [15], SUMO4 [16], and SLAMF1 [17]), Morocco (HLA [18]), Egypt (PADI4 [19], TRAF1/C5, and STAT4 [20]), and South Africa (HLA [21], IL-10 [22], and p53 [23]). RA has uncommonly been reported in Black Africans in West and Middle Africa and its prevalence there is still unknown [24, 25]. A few studies performed from the 1960s to the 1990s on the frequency of the disease suggested the rarity of RA in rural West Africa [26, 27]. Recent reports from West and Middle Africa studied epidemiological, clinical, and serological profiles of RA patients in small series [25, 28–31]. To the best of our knowledge, only two small genetic studies [29, 32] have been performed so far in West/Middle Africa. A study performed in Senegal showed that the risk of developing RA was associated with HLA-DR10 but not HLA-DR4 [32]. We recently reported an important difference in the proportion of SE-positive patients in Cameroon compared with European patients, despite a similar proportion of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody (anti-CCP) positivity, suggesting that the contribution of other non-HLA genetic factors to disease susceptibility could also differ between Caucasians and Black Africans [29]. However, no genetic study of non-HLA markers of RA susceptibility has ever been performed in patients originating from ethnic groups of West or Middle Africa, although this region of Black Africa comprises over 350 million inhabitants.

Using a previously characterized cohort of Cameroonian patients with RA [29], we aimed to determine whether Caucasian non-HLA RA susceptibility loci are shared with Black African patients with RA, as has been shown for Black Americans [7]. Because the small size of the cohort prevented us from drawing any conclusions at the individual SNP level, we computed an aggregated genetic risk score (GRS) [33] to cumulatively test the association of Caucasian RA susceptibility SNPs as a whole with disease susceptibility in Cameroon.

Materials and methods

Patients and data collection

This study was carried out on 56 RA patients recruited from the outpatient Rheumatology Clinic of Yaoundé Central Hospital in Cameroon and on 50 healthy controls recruited among medical students and hospital workers in Yaoundé. Approval of the Cameroon National Ethical Committee was obtained prior to the study, and informed consent was obtained from all patients and controls included in this study. Detailed patient and control characteristics have been reported previously [29]. Publicly available genotypes from 119 unrelated Yoruba individuals in Ibadan, Nigeria (YRI) from the International HapMap Project, phases I+II+III, release #28 of August 2010 [34, 35], were incorporated in the analysis. No phenotypic information (apart from gender) was collected with the YRI samples, and medical conditions of the donors are unknown. However, owing to the low prevalence of RA and other autoimmune conditions in Nigeria, the YRI samples have been considered to be non-RA samples and used as 'controls'. Publicly available allele frequencies calculated from 110 unrelated Luhya individuals in Webuye, Kenya (LWK) from the International HapMap Project (release #28) were retrieved by using SPSmart [36, 37]. Nine thousand three hundred five individuals from the UK RA Genetics Consortium (UKRAG), comprising 5,024 RA cases and 4,281 controls, were available for analysis. Patients' and controls' characteristics and genotyping have been reported previously [38]. Anti-CCP status for Cameroonian and UK samples has been determined with the second-generation CCP (CCP2) assay.

Single-nucleotide polymorphism selection

Caucasian confirmed RA susceptibility SNPs were selected from the large meta-analysis by Stahl and colleagues [1]. Apart from the HLA-DRB1*0401 tag (rs6910071), all SNPs, or good proxies (r2 >0.9 using the 1,000 Genome reference panel for Caucasians - CEU), were available as part of a 67-SNP set used for high-throughput genotyping at our laboratory. This set of SNPs has been described in detail [39].

Genotyping

Sixty-seven SNP markers were genotyped in Cameroonian samples by using Sequenom MassArray technology in accordance with the instructions of the manufacturer (Sequenom, San Diego, CA, USA). Patients with greater than 10% missing genotype data and SNPs with less than 90% genotyping success rate or in Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium (P <0.001) were excluded, prior to analysis, as part of quality control procedures.

Genetic risk score

A Caucasian GRS was computed according to the method of Karlson and colleagues [33]. Briefly, 28 Caucasian confirmed RA susceptibility SNPs with available genotype in the Caucasian (UKRAG) and African (Cameroon and YRI) populations were used. Genotypes were coded as 0, 1, or 2, corresponding to the number of risk alleles carried by an individual. Missing genotypes in UKRAG cases, controls, African cases, or controls were replaced by twice the risk allele frequency of UKRAG cases, controls, African cases, or controls with available genotypes, respectively. The natural logarithms of the odds ratios (ORs) taken from the meta-analysis by Stahl and colleagues (Table 2 of [1]) were used to weight the risk allele count and compute the GRS. For the newly identified susceptibility markers by Stahl and colleagues (Table 3 of [1]), the ORs from the replication analysis were used in order to avoid the 'winner's curse' effect.

Statistical analysis

All quality control steps were performed by using the PLINK software package [40]. Subsequent statistical analysis was performed with Stata version 10.1 (Stata Statistical Software: Release 10; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Correlation calculations of minor allele frequencies (MAFs) between different cohorts/populations were performed by using linear regression. Association analyses between disease susceptibility and GRS were performed with logistic regression.

Results

Cohort characteristics and genotyping results

Cameroonian RA cases and controls collected previously [29] were genotyped for a set of 67 susceptibility SNPs. Basic cohort characteristics of the 43 Cameroonian patients and 44 controls available for analysis after genotyping and quality control procedures do not differ from the characteristics of the entire cohort as presented previously [29] and are compared in Table 1 with basic characteristics of UK and YRI individuals. Only independent SNPs from the meta-analysis by Stahl and colleagues were considered for our analysis, which consisted of a set of 32 non-HLA susceptibility SNPs. rs934734 (SPRED2) and rs540386 (RAG1/TRAF6) completely failed genotyping. rs6859219 (ANKRD55/IL6ST) and rs10488631 (IRF5) genotypes or proxies were not available in UKRAG. Therefore, 28 independent confirmed Caucasian RA non-HLA susceptibility markers (Table 2) had available genotypes for analysis in the three datasets (Cameroon, UKRAG, and YRI). In addition, genotypes for rs6910071, the HLA-DRB1*0401 tag [1], were available for YRI individuals, and four-digit HLA typing was available for the Cameroonian cohort and UKRAG.

Minor allele frequencies of Caucasian rheumatoid arthritis susceptibility single-nucleotide polymorphisms differ importantly between West/Central Africans and Caucasians

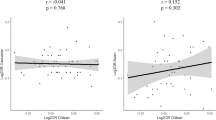

Nigeria and Cameroon are neighboring countries from Central/West Africa. Although no MAF filtering was applied and the number of Cameroonian controls was very low, the MAFs of the 28 Caucasian RA susceptibility SNPs were very tightly correlated between Cameroonian controls and YRI individuals (correlation coefficient = 93.8%, P = 1.7 × 10-13). Therefore, YRI and Cameroonian controls were pooled together for further analysis and referred to as African samples, totaling 206 individuals (43 cases and 163 controls). Interestingly, the MAF of Caucasian RA susceptibility SNPs showed no correlation at all between West/Central African controls and UK controls (correlation coefficient = 30.4%, P = 0.115) (Figure 1) and differed importantly for most of the markers considered here: out of 28 SNPs, only 6 differ by less than 10% and 13 differ by more than 20%. rs10760130 (TRAF1/C5) shows the strongest difference, with an allele frequency of 44%, in the UK for the G allele (minor and risk allele), whereas the G allele is the major allele, with a frequency of 93%, in Africa. Although the MAF is between 10% and 27% for rs12746613 (FCGR2A), rs2476601 (PTPN22), rs6822844 (IL2/IL21), and rs2104286 (IL2RA) in the UK controls, the MAF for those polymorphisms is below 2% in African controls. By contrast, rs5029937 (TNFAIP3) and rs13315591 (DNASE1L3/PXK), which display low MAFs in the UK (3.5% and 7.8%, respectively), show a frequency of above 40% in Africa.

Lack of correlation between minor allele frequencies (MAFs) of non-HLA rheumatoid arthritis susceptibility single-nucleotide polymorphisms in Caucasians (UK) and Africans. The MAF of each polymorphism presented in Table 2 in the UK (MAF_UK) is compared with the frequency of the same allele in Africa (MAF_Africa). 'Minor' refers to a frequency of lower than 50% in the UK. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms with an 'MAF_Africa' of greater than 50% are minor alleles in the UK but major alleles in Africa.

Caucasian non-HLA RA susceptibility SNPs, considered in aggregate, do not confer disease risk in Africa

The low number of African RA cases prevented an association study at the individual SNP level. To test the cumulative association of 28 Caucasian non-HLA confirmed RA susceptibility SNPs, we computed a weighted Caucasian GRS, a widely used strategy in complex disease genetics to summarize the effect of multiple markers within a single variable [33, 41–44]. The Caucasian GRS showed a strong and highly significant association with RA in UKRAG (OR = 2.87, 95% CI 2.60 to 3.17, P = 2.7 × 10-96) when all UKRAG cases and controls were incorporated in the analysis. To investigate the association of the GRS in small samples, 1,000 random samples of 43 UKRAG cases and 163 UKRAG controls were tested and the distribution of the ORs was plotted (Figure 2). The 1,000 ORs ranged from 0.93 to 10.00. The Caucasian GRS was computed for the African samples but did not predict RA in this population (OR = 0.71, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.74, P = 0.456). By contrast, the OR was smaller than the smallest of the 1,000 ORs obtained in UK samples of the same size (red bar in Figure 2), a situation likely to occur by chance in less than 1 in 1,000 cases. The cumulative association of the 28 Caucasian non-HLA RA susceptibility SNPs is therefore significantly different between the UK and Africa (P <0.001).

The genetic risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis (RA) conferred by a set of 28 Caucasian non-HLA susceptibility single-nucleotide polymorphisms is significantly different in the UK and in Africa. One thousand random samples of 43 RA cases and 163 controls (corresponding to the sample size of the African dataset) were generated out of a UK dataset comprising 5,024 RA cases and 4,281 controls. The distribution of odds ratios for association between the Caucasian genetic risk score (GRS) and disease susceptibility is shown in yellow for Caucasian random samples and in red for Africans.

Although the effects of HLA-DRB1 SE alleles have been previously studied in the Cameroonian cohort, we computed a GRS containing one more parameter: the HLA-DRB1*0401 (hereafter, GRS_0401). rs6910071 was used as a surrogate marker in YRI. GRS_0401 was strongly associated with RA in URKAG (OR = 3.43, 95% CI 3.17 to 3.71, P = 8.7 × 10-206), the ORs of 1,000 random samples ranged from 1.29 to 10.35, and the gap with the OR in Africans (OR = 0.51, 95% CI 0.22 to 1.16, P = 0.107) was even larger.

Discussion

The prevalence of HLA-DRB1 SE alleles is highly variable across populations. Across Europe, for example, the prevalence of HLA-DRB1*0401 has been shown to vary from 4.3% in Spain to 24% in Sweden [45]. A higher prevalence of SE alleles in a population seems to correlate with a higher prevalence of RA [46]: the frequency of the SE is 59% in the Cree and Ojibway, a North American Native people in central Canada who have a higher prevalence of RA than Caucasians living in the same area. Ethnic variations in both the frequency and types of SE-carrying HLA-DRB1 alleles have been reported across different populations [47], but very few studies have been performed in Africa. Previously, we reported a lower prevalence of SE alleles in Cameroon and reviewed the scarce literature on studies performed in Black Africans [29]. In the present study, we investigated the contribution of non-HLA genetic markers to RA susceptibility in Cameroon. In a first step, we compared the MAFs of those polymorphisms between different populations. In a second step, we tested the association of confirmed Caucasian non-HLA RA susceptibility loci 'in aggregate' with disease susceptibility since the number of Cameroonian patients with RA was very low. No study of non-HLA genetic markers of RA susceptibility has ever been conducted before in Black Africans from Central/West Africa.

We pooled YRI individuals and Cameroonian controls on the basis of the observation that MAFs are very similar between those two datasets. Although samples have been collected from two neighboring countries, population stratification issues are possible. The low number of SNPs and samples tested here prevented us from addressing this possibility directly. There are more than 2,000 distinct language groups in Africa; ethnic origin, language, geographical location, and genetic differences correlate, so that population structure and genetic diversity are much larger on the African continent than anywhere else in the world [48, 49]. Tishkoff and colleagues [49] studied 113 geographically diverse African populations, including 37 Cameroonian (including Bamoun, Lemande, and Bulu) and 9 Nigerian (including Yoruba) populations. Phylogenetic and population structure analyses showed that most of the Cameroonian populations are closely related genetically and that the genetic distance between them and Yoruba is small. Most Nigerian and Cameroonian populations belong to the West/Central Africa population cluster. However, the East Africa cluster - containing, for example, the Luhya population in Webuye, Kenya (LWK) - is genetically more distant. As an indirect way to estimate the putative impact of within-population structure on our results, we compared the MAFs of non-HLA RA susceptibility loci between Cameroonian controls and LWK individuals (MAFs of 24 SNPs out of 28 studied here were publically available for LWK; see Materials and methods). MAFs of Cameroonian controls and LWK individuals were as tightly correlated (correlation coefficient = 95.1%, P = 1.2 × 10-12) as were MAFs between Cameroonian controls and YRI individuals (correlation coefficient = 93.8%, P = 1.7 × 10-13). However, there was no correlation between MAFs of LWK and UK controls (correlation coefficient = 22.6%, P = 0.29). These findings are compatible with the out-of-Africa hypothesis of human origins and the associated population bottlenecks, which apparently resulted in the alteration of the MAFs studied here. Given the similarity in MAFs across African populations that are more distantly related (West and East Africa), within-population admixture in our case control study of Yoruba/Cameroonian individuals is unlikely to confound the findings. Moreover, population stratification issues are less likely to affect conclusions based on an aggregate GRS than conclusions at the individual SNP level.

Although the sample size is small, there is no doubt that the risk allele frequency of Caucasian RA susceptibility loci is very different in the African samples available. The vast majority of Caucasian susceptibility loci are common genetic variants for reasons related to study design and power issues. Polymorphisms with an allele frequency close to 50% should be detected even in small samples; however, several were barely detectable in the African control samples.

As expected, the Caucasian GRS showed a strong and significant association in the large UK cohort studied here. Even when 1,000 random samples of as few as 43 UK RA cases and 163 UK controls (size of the African sample) were tested for the association of the GRS with RA, the vast majority of them showed an OR of larger than one (997 of 1,000) or a P value of smaller than 0.05 (763 of 1,000). The OR in the African sample was much smaller than the smallest OR in the UK, a situation that is extremely unlikely to be explained by small sample size (P <0.001). The effect size ratio - that is, ORUK/ORAfrica - is 4.04 (95% CI 1.6 to 10.0). Such a striking difference using a small number of Cameroonian RA samples highlights an important difference in the genetic architecture of RA susceptibility between the UK (or Caucasians) and Cameroon (West/Central Africa).

Several hypotheses can be postulated to explain the effect size ratio. First of all, the currently known Caucasian RA susceptibility loci might constitute a minority of the total RA susceptibility loci and might not be shared with African patients. Indeed, many more susceptibility variants, possibly thousands of SNPs, could contribute to the susceptibility to RA [50]. Secondly, even if those markers are shared, their effect size might be different between Caucasians and Africans. This would explain on its own the difference observed since the Caucasian GRS has been computed by using the Caucasian effect sizes. Thirdly, the confirmed RA susceptibility loci from the meta-analysis by Stahl and colleagues [1] might not be the causal SNPs in Caucasians but SNPs in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with the causal SNP. Fine-mapping experiments for most of those loci have not been performed yet. Therefore, the causal SNP, even if shared between the two populations, might be in tight LD with the Stahl SNPs in Caucasians but not in Africans. Under this hypothesis, an effect size ratio of 4.04 indicates that many of the Stahl SNPs might not be causal. This difference in the genetic architecture of the human genome between Africans and Caucasians can be further illustrated at the MMEL1/TNFRSF14 locus; rs10910099 was used as a proxy for the Stahl SNP rs3890745. The LD (r2) between these two markers is 0.926 when the 1,000 Genome CEU (Caucasian) is used as a reference panel but is 0.662 when the 1,000 Genome YRI panel is used. It is not known which one of the two SNPs, if either, is the causal.

Including the HLA-DRB1*0401 allele in the computation of the GRS further increased the gap between the association pattern in the UK versus Africa, consistent with previously published observations on the low allele frequency of the HLA-DRB1*0401 allele in African patients with RA [29, 32]. Therefore, the genetics of RA differs significantly between the UK and Cameroon in terms of allele frequencies of currently known HLA and non-HLA markers and their aggregate effect on disease susceptibility. Further studies are required in larger samples of African RA patients of different origins to investigate whether this statement can be generalized for Caucasians and Black Africans. Owing to the difference in the LD structure between Caucasians and African populations, well-powered GWASs of patients with RA will greatly increase our understanding of the contribution of genetic factors to disease susceptibility and allow deeper fine-mapping experiments.

Conclusions

An aggregate GRS based on the independent and confirmed non-HLA Caucasian RA susceptibility SNPs predicts RA in the UK but not in West/Central Africa. The difference in association between the GRS and disease susceptibility is so large that it can be significantly detected even when only 43 Cameroonian RA samples are included in the analysis. This observation strengthens the hypothesis that the genetic architecture of RA susceptibility is different in different ethnic backgrounds and suggests that currently known RA susceptibility SNPs are different or have different effect sizes between Caucasians and Africans. Well-powered GWASs of African patients with RA are required to identify susceptibility loci specific to ethnic groups and to contribute to the fine mapping of currently known loci.

Abbreviations

- anti-CCP:

-

anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody

- CEU:

-

Utah residents with ancestry from northern and western Europe

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- GRS:

-

genetic risk score

- GWAS:

-

genome-wide association study

- LD:

-

linkage disequilibrium

- LWK:

-

Luhya individuals in Webuye: Kenya

- MAF:

-

minor allele frequency

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- RA:

-

rheumatoid arthritis

- SE:

-

shared epitope

- SNP:

-

single-nucleotide polymorphism

- UKRAG:

-

United Kingdom Rheumatoid Arthritis Genetics Consortium

- YRI:

-

Yoruba in Ibadan: Nigeria.

References

Stahl EA, Raychaudhuri S, Remmers EF, Xie G, Eyre S, Thomson BP, Li Y, Kurreeman FA, Zhernakova A, Hinks A, Guiducci C, Chen R, Alfredsson L, Amos CI, Ardlie KG, BIRAC Consortium, Barton A, Bowes J, Brouwer E, Burtt NP, Catanese JJ, Coblyn J, Coenen MJ, Costenbader KH, Criswell LA, Crusius JB, Cui J, de Bakker PI, De Jager PL, Ding B, Emery P, et al: Genome-wide association study meta-analysis identifies seven new rheumatoid arthritis risk loci. Nat Genet. 2010, 42: 508-514. 10.1038/ng.582.

Freudenberg J, Lee HS, Han BG, Shin HD, Kang YM, Sung YK, Shim SC, Choi CB, Lee AT, Gregersen PK, Bae SC: Genome-wide association study of rheumatoid arthritis in Koreans: population-specific loci as well as overlap with European susceptibility loci. Arthritis Rheum. 2011, 63: 884-893.

Kochi Y, Okada Y, Suzuki A, Ikari K, Terao C, Takahashi A, Yamazaki K, Hosono N, Myouzen K, Tsunoda T, Kamatani N, Furuichi T, Ikegawa S, Ohmura K, Mimori T, Matsuda F, Iwamoto T, Momohara S, Yamanaka H, Yamada R, Kubo M, Nakamura Y, Yamamoto K: A regulatory variant in CCR6 is associated with rheumatoid arthritis susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2010, 42: 515-519. 10.1038/ng.583.

Kurreeman FA, Stahl EA, Okada Y, Liao K, Diogo D, Raychaudhuri S, Freudenberg J, Kochi Y, Patsopoulos NA, Gupta N, CLEAR investigators, Sandor C, Bang SY, Lee HS, Padyukov L, Suzuki A, Siminovitch K, Worthington J, Gregersen PK, Hughes LB, Reynolds RJ, Bridges SL, Bae SC, Yamamoto K, Plenge RM: Use of a Multiethnic Approach to Identify Rheumatoid- Arthritis-Susceptibility Loci, 1p36 and 17q12. Am J Hum Genet. 2012, 90: 524-532. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.01.010.

Mori M, Yamada R, Kobayashi K, Kawaida R, Yamamoto K: Ethnic differences in allele frequency of autoimmune-disease-associated SNPs. J Hum Genet. 2005, 50: 264-266. 10.1007/s10038-005-0246-8.

Totaro MC, Tolusso B, Napolioni V, Faustini F, Canestri S, Mannocci A, Gremese E, Bosello SL, Alivernini S, Ferraccioli G: PTPN22 1858C>T polymorphism distribution in Europe and association with rheumatoid arthritis: case-control study and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2011, 6: e24292-10.1371/journal.pone.0024292.

Hughes LB, Reynolds RJ, Brown EE, Kelley JM, Thomson B, Conn DL, Jonas BL, Westfall AO, Padilla MA, Callahan LF, Smith EA, Brasington RD, Edberg JC, Kimberly RP, Moreland LW, Plenge RM, Bridges SL: Most common single-nucleotide polymorphisms associated with rheumatoid arthritis in persons of European ancestry confer risk of rheumatoid arthritis in African Americans. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62: 3547-3553. 10.1002/art.27732.

Perkins EA, Landis D, Causey ZL, Edberg Y, Reynolds RJ, Hughes LB, Gregersen PK, Kimberly RP, Edberg JC, Bridges SL, Consortium for the Longitudinal Evaluation of African Americans with Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Investigators: Association of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in CCR6, TAGAP and TNFAIP3 with rheumatoid arthritis in African Americans. Arthritis Rheum. 2012, 64: 1355-1358. 10.1002/art.33464.

Hughes LB, Morrison D, Kelley JM, Padilla MA, Vaughan LK, Westfall AO, Dwivedi H, Mikuls TR, Holers VM, Parrish LA, AlarcÓn GS, Conn DL, Jonas BL, Callahan LF, Smith EA, Gilkeson GS, Howard G, Moreland LW, Patterson N, Reich D, Bridges SL: The HLA-DRB1 shared epitope is associated with susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis in African Americans through European genetic admixture. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 58: 349-358. 10.1002/art.23166.

Chabchoub G, Teixiera EP, Maalej A, Ben HM, Bahloul Z, Cornelis F, Ayadi H: The R620W polymorphism of the protein tyrosine phosphatase 22 gene in autoimmune thyroid diseases and rheumatoid arthritis in the Tunisian population. Ann Hum Biol. 2009, 36: 342-349. 10.1080/03014460902817968.

Sfar I, Dhaouadi T, Habibi I, Abdelmoula L, Makhlouf M, Ben Romdhane T, Jendoubi-Ayed S, Aouadi H, Ben Abdallah T, Ayed K, Zouari R, Lakhoua-Gorgi Y: Functional polymorphisms of PTPN22 and FcgR genes in Tunisian patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Inst Pasteur Tunis. 2009, 86: 51-62.

Ben HM, Cornelis F, Maalej A, Petit-Teixeira E: A Tunisian case-control association study of a 6q polymorphism in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2012, 32: 1849-1850. 10.1007/s00296-011-1996-6.

Ben Hamad M, Cornelis F, Mbarek H, Chabchoub G, Marzouk S, Bahloul Z, Rebai A, Fakhfakh F, Ayadi H, Petit-Teixeira E, Maalej A: Signal transducer and activator of transcription and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis and thyroid autoimmune disorders. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011, 29: 269-274.

Maalej A, Hamad MB, Rebai A, Teixeira VH, Bahloul Z, Marzouk S, Farid NR, Ayadi H, Cornelis F, Petit-Teixeira E: Association of IRF5 gene polymorphisms with rheumatoid arthritis in a Tunisian population. Scand J Rheumatol. 2008, 37: 414-418. 10.1080/03009740802256327.

Belguith-Maalej S, Hadj-Kacem H, Kaddour N, Bahloul Z, Ayadi H: DNase1 exon2 analysis in Tunisian patients with rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjogren syndrome and healthy subjects. Rheumatol Int. 2009, 30: 69-74. 10.1007/s00296-009-0917-4.

Fakhfakh KE, Bendhifallah I, Zakraoui L, Hamzaoui K: Association of small ubiquitin-like modifier 4 gene polymorphisms with rheumatoid arthritis in a Tunisian population. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011, 29: 751-

Chabchoub G, Petit-Teixeira E, Maalej A, Pierlot C, Bahloul Z, Cornelis F, Ayadi H: Lack of association between signaling lymphocytic activation molecule family member 1 gene and rheumatoid arthritis in the French and Tunisian populations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006, 65: 1538-1539. 10.1136/ard.2006.052209.

Atouf O, Benbouazza K, Brick C, Bzami F, Bennani N, Amine B, Hajjaj-Hassouni N, Essakali M: HLA polymorphism and early rheumatoid arthritis in the Moroccan population. Joint Bone Spine. 2008, 75: 554-558. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2008.01.027.

bd-Allah SH, El-Shal AS, Shalaby SM, Pasha HF, El-Saoud AM, El-Najjar AR, El-Shahawy EE: PADI4 polymorphisms and related haplotype in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Joint Bone Spine. 2012, 79: 124-128. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2011.07.006.

Mohamed RH, Pasha HF, El-Shahawy EE: Influence of TRAF1/C5 and STAT4 genes polymorphisms on susceptibility and severity of rheumatoid arthritis in Egyptian population. Cell Immunol. 2012, 273: 67-72. 10.1016/j.cellimm.2011.11.005.

Meyer PW, Hodkinson B, Ally M, Musenge E, Wadee AA, Fickl H, Tikly M, Anderson R: HLA-DRB1 shared epitope genotyping using the revised classification and its association with circulating autoantibodies, acute phase reactants, cytokines and clinical indices of disease activity in a cohort of South African rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011, 13: R160-10.1186/ar3479.

MacKay K, Milicic A, Lee D, Tikly M, Laval S, Shatford J, Wordsworth P: Rheumatoid arthritis susceptibility and interleukin 10: a study of two ethnically diverse populations. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003, 42: 149-153. 10.1093/rheumatology/keg054.

Moodley D, Mody GM, Chuturgoon AA: Functional analysis of the p53 codon 72 polymorphism in black South Africans with rheumatoid arthritis--a pilot study. Clin Rheumatol. 2010, 29: 1099-1105. 10.1007/s10067-010-1505-4.

Mijiyawa M: Epidemiology and semiology of rheumatoid arthritis in Third World countries. Rev Rhum Engl Ed. 1995, 62: 121-126.

Ouedraogo DD, Singbo J, Diallo O, Sawadogo SA, Tieno H, Drabo YJ: Rheumatoid arthritis in Burkina Faso: clinical and serological profiles. Clin Rheumatol. 2011, 30: 1617-1621. 10.1007/s10067-011-1831-1.

Silman AJ, Ollier W, Holligan S, Birrell F, Adebajo A, Asuzu MC, Thomson W, Pepper L: Absence of rheumatoid arthritis in a rural Nigerian population. J Rheumatol. 1993, 20: 618-622.

Mody GM: Rheumatoid arthritis and connective tissue disorders: sub-Saharan Africa. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1995, 9: 31-44. 10.1016/S0950-3579(05)80141-4.

Bileckot R, Malonga AC: Rheumatoid arthritis in Congo-Brazzaville. A study of thirty-six cases. Rev Rhum Engl Ed. 1998, 65: 308-312.

Singwe-Ngandeu M, Finckh A, Bas S, Tiercy JM, Gabay C: Diagnostic value of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptides and association with HLA-DRB1 shared epitope alleles in African rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010, 12: R36-10.1186/ar2945.

Adelowo OO, Ojo O, Oduenyi I, Okwara CC: Rheumatoid arthritis among Nigerians: the first 200 patients from a rheumatology clinic. Clin Rheumatol. 2010, 29: 593-597. 10.1007/s10067-009-1355-0.

Ndongo S, Lekpa FK, Ka MM, Ndiaye N, Diop TM: Presentation and severity of rheumatoid arthritis at diagnosis in Senegal. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009, 48: 1111-1113. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep178.

Dieye A, Diallo S, Diatta M, Thiam A, Ndiaye R, Bao O, Sarthou JL: [Identification of HLA-DR alleles for susceptibility to rheumatoid polyarthritis in Senegal]. Dakar Med. 1997, 42: 111-113. In French

Karlson EW, Chibnik LB, Kraft P, Cui J, Keenan BT, Ding B, Raychaudhuri S, Klareskog L, Alfredsson L, Plenge RM: Cumulative association of 22 genetic variants with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis risk. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010, 69: 1077-1085. 10.1136/ard.2009.120170.

International HapMap Project homepage. [http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov]

The International HapMap Consortium: The International HapMap Project. Nature. 2003, 426: 789-796. 10.1038/nature02168.

SPSmart homepage. [http://spsmart.cesga.es/]

Amigo J, Salas A, Phillips C, Carracedo A: SPSmart: adapting population based SNP genotype databases for fast and comprehensive web access. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008, 9: 428-10.1186/1471-2105-9-428.

Morgan AW, Thomson W, Martin SG, Yorkshire Early Arthritis Register Consortium, Carter AM, UK Rheumatoid Arthritis Genetics Consortium, Erlich HA, Barton A, Hocking L, Reid DM, Harrison P, Wordsworth P, Steer S, Worthington J, Emery P, Wilson AG, Barrett JH: Reevaluation of the interaction between HLA-DRB1 shared epitope alleles, PTPN22, and smoking in determining susceptibility to autoantibody-positive and autoantibody-negative rheumatoid arthritis in a large UK Caucasian population. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 60: 2565-2576. 10.1002/art.24752.

Viatte S, Plant D, Lunt M, Fu B, Flynn E, Parker B, Galloway J, Solymossy C, Worthington J, Symmons DP, Dixey J, Young A, Barton A: Investigation of rheumatoid arthritis genetic susceptibility markers in the Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Study (ERAS) provides further replication of the TRAF1 association with radiological damage. J Rheumatol. 2013,

Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, Sham PC: PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007, 81: 559-575. 10.1086/519795.

Chen H, Poon A, Yeung C, Helms C, Pons J, Bowcock AM, Kwok PY, Liao W: A genetic risk score combining ten psoriasis risk loci improves disease prediction. PLoS One. 2011, 6: e19454-10.1371/journal.pone.0019454.

Chibnik LB, Keenan BT, Cui J, Liao KP, Costenbader KH, Plenge RM, Karlson EW: Genetic risk score predicting risk of rheumatoid arthritis phenotypes and age of symptom onset. PLoS One. 2011, 6: e24380-10.1371/journal.pone.0024380.

De Jager PL, Chibnik LB, Cui J, Reischl J, Lehr S, Simon KC, Aubin C, Bauer D, Heubach JF, Sandbrink R, Tyblova M, Lelkova P, Steering committee of the BENEFIT study; Steering committee of the BEYOND study; Steering committee of the LTF study; Steering committee of the CCR1 study, Havrdova E, Pohl C, Horakova D, Ascherio A, Hafler DA, Karlson EW: Integration of genetic risk factors into a clinical algorithm for multiple sclerosis susceptibility: a weighted genetic risk score. Lancet Neurol. 2009, 8: 1111-1119. 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70275-3.

Lluis-Ganella C, Subirana I, Lucas G, Tomás M, Muñoz D, Sentí M, Salas E, Sala J, Ramos R, Ordovas JM, Marrugat J, Elosua R: Assessment of the value of a genetic risk score in improving the estimation of coronary risk. Atherosclerosis. 2012, 222: 456-463. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.03.024.

van der Woude D, Lie BA, Lundström E, Balsa A, Feitsma AL, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, Verduijn W, Nordang GB, Alfredsson L, Klareskog L, Pascual-Salcedo D, Gonzalez-Gay MA, Lopez-Nevot MA, Valero F, Roep BO, Huizinga TW, Kvien TK, Martín J, Padyukov L, de Vries RR, Toes RE: Protection against anti-citrullinated protein antibody-positive rheumatoid arthritis is predominantly associated with HLA-DRB1*1301: a meta-analysis of HLA-DRB1 associations with anti-citrullinated protein antibody-positive and anti-citrullinated protein antibody-negative rheumatoid arthritis in four European populations. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62: 1236-1245. 10.1002/art.27366.

Peschken CA, Esdaile JM: Rheumatic diseases in North America's indigenous peoples. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1999, 28: 368-391. 10.1016/S0049-0172(99)80003-1.

Del RincÓn I, Battafarano DF, Arroyo RA, Murphy FT, Fischbach M, Escalante A: Ethnic variation in the clinical manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis: role of HLA-DRB1 alleles. Arthritis Rheum. 2003, 49: 200-208. 10.1002/art.11000.

Teo YY, Small KS, Kwiatkowski DP: Methodological challenges of genome-wide association analysis in Africa. Nat Rev Genet. 2010, 11: 149-160.

Tishkoff SA, Reed FA, Friedlaender FR, Ehret C, Ranciaro A, Froment A, Hirbo JB, Awomoyi AA, Bodo JM, Doumbo O, Ibrahim M, Juma AT, Kotze MJ, Lema G, Moore JH, Mortensen H, Nyambo TB, Omar SA, Powell K, Pretorius GS, Smith MW, Thera MA, Wambebe C, Weber JL, Williams SM: The genetic structure and history of Africans and African Americans. Science. 2009, 324: 1035-1044. 10.1126/science.1172257.

Stahl EA, Wegmann D, Trynka G, Gutierrez-Achury J, Do R, Voight BF, Kraft P, Chen R, Kallberg HJ, Kurreeman FA, Diabetes Genetics Replication and Meta-analysis Consortium; Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium, Kathiresan S, Wijmenga C, Gregersen PK, Alfredsson L, Siminovitch KA, Worthington J, de Bakker PI, Raychaudhuri S, Plenge RM: Bayesian inference analyses of the polygenic architecture of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Genet. 2012, 44: 483-489. 10.1038/ng.2232.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the International HapMap Consortium and the Yoruba people of Ibadan, Nigeria, who participated in public consultations and community engagements, and the people in this community and from Yaoundé, Cameroon, who were generous in donating their blood samples. This work was funded by a core programme grant from Arthritis Research UK (grant reference number 17752). SV is supported by a research grant from the Swiss Foundation for Medical-Biological Scholarships (SSMBS), managed by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant reference number PASMP3_134380). This grant is financed by a donation of Novartis (Basel, Switzerland) to the SSMBS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

SV performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. EF performed the genotyping and helped to process collected clinical samples. ML participated in the statistical analysis. JB and SB helped to process collected clinical samples. CG is one of the founders and principal investigators on the Cameroonian cohort and helped to conceive the study and participated in its design and coordination. MS-N is one of the founders and principal investigators on the Cameroonian cohort and collected phenotypic information and clinical samples. AB helped to conceive the study and participated in its design and coordination. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Viatte, S., Flynn, E., Lunt, M. et al. Investigation of Caucasian rheumatoid arthritis susceptibility loci in African patients with the same disease. Arthritis Res Ther 14, R239 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/ar4082

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/ar4082