Abstract

The concept of osteoimmunology is based on growing insight into the links between the immune system and bone at the anatomical, vascular, cellular, and molecular levels. In both rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and ankylosing spondylitis (AS), bone is a target of inflammation. Activated immune cells at sites of inflammation produce a wide spectrum of cytokines in favor of increased bone resorption in RA and AS, resulting in bone erosions, osteitis, and peri-inflammatory and systemic bone loss. Peri-inflammatory bone formation is impaired in RA, resulting in non-healing of erosions, and this allows a local vicious circle of inflammation between synovitis, osteitis, and local bone loss. In contrast, peri-inflammatory bone formation is increased in AS, resulting in healing of erosions, ossifying enthesitis, and potential ankylosis of sacroiliac joints and intervertebral connections, and this changes the biomechanical competence of the spine. These changes in bone remodeling and structure contribute to the increased risk of vertebral fractures (in RA and AS) and non-vertebral fractures (in RA), and this risk is related to severity of disease and is independent of and superimposed on background fracture risk. Identifying patients who have RA and AS and are at high fracture risk and considering fracture prevention are, therefore, advocated in guidelines. Local peri-inflammatory bone loss and osteitis occur early and precede and predict erosive bone destruction in RA and AS and syndesmophytes in AS, which can occur despite clinically detectable inflammation (the so-called 'disconnection'). With the availability of new techniques to evaluate peri-inflammatory bone loss, osteitis, and erosions, peri-inflammatory bone changes are an exciting field for further research in the context of osteoimmunology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The concept of osteoimmunology emerged more than a decade ago and is based on rapidly growing insight into the functional interdependence between the immune system and bone at the anatomical, vascular, cellular, and molecular levels [1]. In 1997, the receptor activator of the nuclear factor-kappa-B ligand (RANKL)/RANK/osteoprotegerin (OPG) pathway was identified as a crucial molecular pathway of the coupling between osteoblasts and osteoclasts [2]. It appeared that not only osteoblasts but also activated T lymphocytes, which play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and many other inflammatory cells can produce RANKL, which stimulates the differentiation and activation of osteoclasts [3]. These findings have contributed to the birth of osteoimmunology as a discipline.

Because of the multiple interconnections and interactions of bone and the immune system, bone is a major target of chronic inflammation in RA and ankylosing spondylitis (AS). Inflammation increases bone resorption and results in suppressed local bone formation in RA and locally increased bone formation in AS, causing a wide spectrum of bone involvement in RA and AS [4, 5].

Osteoporosis has been defined as a bone mineral density (BMD) of lower than 2.5 standard deviations of healthy young adults and in daily practice is measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) at the spine and hip [6]. However, the bone disease component in RA and AS is much more complex, especially around the sites of inflammation. We reviewed the literature on the quantification of local and general bone changes and their relation to the structural damage of bone, disease activity parameters, and fracture risk in the context of osteoimmunology, both in RA and AS. We have chosen to focus on RA and AS since these inflammatory rheumatic diseases have the highest prevalence and since, in both diseases, characteristic but different types of bone involvement may occur.

Anatomical and molecular cross-talk between bone and the immune system

Multiple anatomical and vascular contacts and overlapping and interacting cellular and molecular mechanisms are involved in the regulation of bone turnover and the immune system, so that one can no longer view either system in isolation but should consider bone and the immune system to be an integrated whole [4, 5].

Anatomical connections

Bone, by virtue of its anatomy and vascularization, is at the inside and outside and is in direct and indirect and in close and distant contact with the immune system. At the inside, bones are the host for hematopoiesis, allowing bone and immune cells to cooperate locally. At the outside, bone is in direct contact with the periost, the synovial entheses within the joints at the periost- and cartilage-free bare area [7], the fibrous tendon entheses, the calcified component of cartilage and tendon insertions, and the intervertebral discs.

Until recently, it was thought, on the basis of plain radiographs of the hands, that there is only rarely a direct anatomical connection between bone marrow and joint space. Bone erosions have been found in hand joints of presumably healthy controls in less than 1% with plain radiology and in 2% with MRI [8]. However, exciting new data have shown that, with the use of high-resolution quantitative computer tomography (HRqCT), small erosions (<1.9 mm) in the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints can be found in 37% of healthy subjects without any signs or symptoms of RA, indicating that small erosions are not specific for RA [9]. Large erosions (>1.9 mm) were found to be specific for RA. Interestingly, 58% of erosions detected by HRqCT in healthy volunteers were not visible on plain radiographs [9]. In healthy controls, the erosions in the MCP joints were not randomly located but were located at the bare area and at high-pressure points adjacent to ligaments, which are erosion-prone sites in RA [10]. Bone erosions are also extremely common in healthy controls in the entheses [11] and in the vertebral cortices covered by periost and the intervertebral discs (in AS) [12]. The immune system, bone, and its internal and external surfaces not only are connected by these local anatomical connections but also are connected with the general circulation by the main bone nutrition arteries and locally with the periost (by its vasculature that perforates cortical bone) and within the bone compartment by attachments of fibrous entheses and the calcified components of cartilage and fibrocartilage up to the tidemark, which separates calcified from non-calcified components of cartilage and tendons [11].

Molecular connections

Bone cells exert major effects on the immune system. Bone cells interact with immune cells and play an essential role in the development of the bone marrow space during growth [13] and during fracture healing [14]. Osteoblasts play a central role in the regulation of renewal and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and of B cells in niches near the endosteum [15–17]. Metabolic pathways of the osteoblast which are involved in bone remodeling are also involved in the regulation of HSCs by osteoblasts, such as the calcium receptor, parathyroid hormone (PTH), bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), the Wnt signaling, and cell-cell interactions by the NOTCH (Notch homolog, translocation-associated (Drosophila)) signaling pathway [15–19]. On the other hand, multiple cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors of immune cells such as T and B cells, fibroblasts, dendritic cells, and macrophages directly or indirectly regulate osteoblast and osteoclast activity by producing or influencing the production of the RANKL/RANK/OPG pathway, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), interferon-gamma (IFNγ), and interleukins (such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-15, IL-17, IL-18, and IL-23) and the Wnt signaling with involvement of Dikkoppf (DKK), sclerostin, and BMP [4, 5, 19–21].

In RA, bone loss and bone destruction are dependent on the imbalance between osteoclastogenic and anti-osteoclastogenic factors. T-cell infiltration in the synovium is a hallmark of RA. TH17 cells, whose induction is regulated by dendritic cells that produce transforming growth factor-beta, IL-6, and IL-23, secrete IL-17, which induces RANKL in fibroblasts and activates synovial macrophages to secrete TNFα, IL-1, and IL-6, which directly or indirectly (via fibroblasts producing RANKL) activate osteoclastogenesis [1]. Other direct or indirect osteoclastogenic factors include monocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor, IL-11, IL-15, oncostatin M, leukemia inhibitor factor, and prostaglandins of the E series (PGE) [22–24]. Inhibitors of osteoclastogenesis in RA include TH1 (producing IFNγ) and TH2 (producing IL-4) cells and possibly T helper regulatory (THREG) cells [1].

In AS, increased bone formation, as reflected by syndesmophyte formation in the spine, is related to decreased serum levels of DKK [25] and sclerostin [21], both inhibitors of bone formation, and to serum levels of BMP, which is essential for enchondral bone formation [26], and of CTX-II [27], which reflects cartilage destruction that occurs during enchondral bone formation in syndesmophytes [26–28]. There is, thus, increasing evidence that immune cells and cytokines are critically responsible for the changes in bone resorption and formation and vice versa, resulting in changes in bone quality in chronic inflammatory conditions. These conditions include RA, spondylarthopathies (SpAs) (AS, psoriatic arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease), systemic lupus erythematosis, juvenile RA, periodontal diseases, and even postmenopausal osteoporosis [29]. We reviewed the literature on the quantification of bone involvement in RA and AS. For an in-depth discussion of the underlying metabolic pathways, a topic that is beyond the scope of this review, the reader is referred to other reviews [4, 5].

Histology of bone in rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis Bone resorption

Bone resorption is increased in RA and AS. In RA, this has been demonstrated histologically by the presence of activated osteoclasts in the pannus at the site of bone erosions [30, 31], in the periarticular trabecular and cortical bone [32, 33], and, in a general way, in sites distant from inflammation [34]. In AS, osteoclastic bone resorption has been demonstrated in the sacroiliac joints [35–37].

The introduction of MRI has shed new light on the involvement of subchondral bone and bone marrow in RA and AS (Figure 1). Periarticular MRI lesions have been described technically as bone edema (on short T inversion recovery (STIR), indicating that fatty bone marrow is replaced by fluid) and osteitis (on T1 after IV gadolinium) [38] and histologically as osteitis as inflammation has been demonstrated on histological examination of these lesions [33]. In joint specimens of patients with RA and with MRI signs of bone edema, histological correlates have been studied in specimens obtained at the time of joint replacement and have shown the presence of greater numbers of osteoclasts than in controls and in patients with osteoarthritis and the presence of T cells, B-cell follicles, plasma cells, macrophages, decreased trabecular bone density, and increased RANKL expression [33].

Osteitis is also a major component of AS [39–42]. Osteitis was described by histology of the vertebrae in 1956 [43] and occurs early in the disease and predicts the occurrence of bone erosions [39]. It has been shown that, as in RA, these lesions contain activated immune cells and osteoclasts [44, 45]. In contrast to RA, these lesions differ in their location: in the vertebrae, the entheses, the periost of vertebrae and around the joints, the discovertebral connections, the intervertebral joints and the sacroiliac joints, and, to a lesser degree, the peripheral joints, mainly hips and shoulders (Figure 1) [46, 47].

Bone formation

In spite of the presence of cells with early markers of osteoblasts in and around erosions in RA, bone formation is locally suppressed [48]. This uncoupling of bone resorption and bone formation contributes to the only rare occurrence of healing bone erosions [49] and results in persisting direct local connections between the joint cavity and subchondral bone and thus between synovitis and osteitis. In contrast, in AS, local peri-inflammatory bone formation is increased, resulting in healing of erosions, ossifying enthesitis, and potential ankylosis of sacroiliac joints and of intervertebral connections. The ossification of entheses and sacroiliac joints involves calcification of the fibrocartilage, followed by enchondral bone formation; that is, calcified cartilage is replaced by bone through osteoclastic resorption of calcified cartilage and deposition of bone layers on the inside of the resorption cavity with a very slow evolution and with prolonged periods of arrest [50].

Bone biomarkers

In patients with RA, markers of bone resorption are increased in comparison with controls [51]. Correlations between bone markers, bone erosions, and bone loss in RA varied according to study designs (cross-sectional or longitudinal), patient selection, and study endpoints (disease activity score, radiology, and MRI) [52]. Baseline markers of bone and cartilage breakdown (CTX-I and CTX-II) and the RANKL/OPG ratio were related to short-and long-term (up to 11 years for RANKL/OPG) progression of joint damage in RA, independently of other risk factors of bone erosions [53, 54]. Increased markers of bone resorption were related to increased fracture risk [49]. Studies on markers of bone formation in RA, such as osteocalcin, are scarce and show contradictory results, except low serum values in glucocorticoid (GC) users [55, 56].

In AS, markers of bone resorption were increased [27, 57] and were related to inflammation as measured by serum IL-6 [58]. Increased serum levels of RANKL have been reported [59] with decreased OPG [60, 61], and RANKL expression is increased in peripheral arthritis of SpA [62]. Markers of bone formation (type I collagen N-terminal propeptide, or PINP) were related to age, disease duration, and markers of bone resorption (CTX-I) but not with low BMD in the hip or spine [63]. Markers of cartilage breakdown (CTX-II) were related to progression of the modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spine Score (mSASSS) and the appearance of syndespomphytes [27].

Imaging of bone in rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis

Many methods, including histomorphometry, imaging (Figure 2), and biomarkers, have been used to study the effect of inflammation on structural and functional aspects of bone in RA and AS. Conventional radiology of the peripheral joints and the spine is used for identifying erosions, joint space narrowing, enthesitis, and syndesmophytes for diagnosis; assessment of disease progression; and standardized scoring in clinical trials, but it is estimated that bone loss of less than 20% to 40% cannot be detected on plain radiographs [64].

Methods to quantify bone changes in the hands and vertebrae. (a) Methods to quantify periarticular bone changes. (b) Methods to quantify vertebral bone changes. μCT, micro-computed tomography; DXA, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry; DXR, digitalized radiogrammetry; HRDR, high-resolution digital radiology; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; QCT, quantitative computer tomography; QUS, quantitative ultrasound; VFA, vertebral fracture assessment.

Methods that quantify changes in periarticular bone include radiogrammetry, digitalized radiogrammetry (DXR) [65], peripheral dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (pDXA) [66], quantitative ultrasound (QUS) [67], high-resolution digital radiography [68], high-resolution peripheral qCT [9], and MRI [8], and methods that quantify changes in the vertebrae include DXA, qCT, MRI, and morphometry by vertebral fracture assessment on x-rays or DXA images [69] (Figure 2). At other sites of the skeleton, single x-ray absorptiometry, qCT, MRI, DXA, and QUS are available; of these, DXA is considered the gold standard [70]. Semiquantitative scoring of osteitis on MRI in the vertebrae has been standardized [40, 42, 71]. Local peri-inflammatory bone formation can be evaluated semiquantitatively in a standardized way on radiographs for scoring of syndesmophytes [41, 42, 72]. These techniques differ in regions of interest that can be measured, in the ability to measure cortical and trabecular bone separately or in combination, and in radiation dose, cost, and precision [64, 73] (Table 1).

Periarticular bone loss and osteitis in rheumatoid arthritis

On plain radiographs of the hands, periarticular trabecular bone loss results in diffuse or spotty demineralization and blurred or glassy bone and cortical bone loss in tunneling, lamellation, or striation of cortical bone [74] (Figure 3). Quantification of bone in the hands has consistently shown that patients with RA have lower BMD than controls and lose bone during follow-up, depending on treatment (see below) [75–77]. Cortical bone loss occurs early in the disease, preferentially around affected joints and before generalized osteoporosis can be detected [51, 78]. In studies using peripheral qCT at the forearm, trabecular bone loss was more prominent than cortical bone loss in RA patients using GCs [79, 80].

Hand bone loss is a sensitive outcome marker for radiological progression. The 1-year hand bone loss measured by DXR predicted the 5- and 10-year occurrence of erosions in RA [73, 81] and was a useful predictor of the bone destruction in patients with early unclassified polyarthritis [82]. Hand bone loss measured by DXR correlated with C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), disease activity score using 28 joint counts (DAS28), the presence of rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody (anti-CCP), health assessment questionnaire (HAQ) score, disease duration, and Sharp score [66, 83, 84]. In the forearm and calcaneus, trabecular but not cortical periarticular bone loss measured by DXA in early RA correlated with ESR, CRP, RF, and HAQ score [80]. DXR correlated with hip BMD and the presence of morphometric vertebral fractures and non-vertebral fractures in RA [85]. DXR-BMD performed as well as other peripheral BMD measurements for prediction of wrist, hip, and vertebral fractures in the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures [86].

Periarticular osteitis is a frequent finding in RA (45% to 64% of patients with RA) and has remarkable similarities with periarticular bone loss in RA (Figure 1) [87]. Osteitis is found early in the disease process, is predictive of radiographic damage, including erosions and joint space narrowing, SF-36 (short-form 36-question health survey) score function, and tendon function, and is related to clinical parameters CRP and IL-6 in early RA and to painful and aggressive disease [87–94]. Scoring of MRI edema has been standardized by OMERACT (Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials) [88]. Osteitis is characterized by trabecular bone loss on histology [66, 84–96], but no studies on the relation between osteitis and quantification of bone loss were found.

Generalized bone loss in rheumatoid arthritis

BMD is a major determinant of the risk of fractures, but the relationship between BMD and fracture risk is less clear in RA than in postmenopausal osteoporosis, indicating that factors other than those captured by measuring BMD are involved in the pathophysiology of fractures in RA.

Patients with RA have a decreased BMD in the spine and hip and consequently have a higher prevalence of osteoporosis [56, 97–101]. However, this was not confirmed in the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMos) [102]. In early untreated RA, BMD was related to longer symptom duration, the presence of RF [103] and anti-CCP [104], disease activity score [105], and the presence and progression of joint damage [106].

The interpretation of longitudinal changes in RA is complicated by the lack of untreated patients, and this limits our insights into the natural evolution of bone changes in RA to the above-mentioned studies. In one study with early untreated RA, bone loss was found in the spine and trochanter for a period of one year [107]. However, Kroot and colleagues [108] did not find bone loss over the course of a 10-year follow-up in RA patients treated with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, except when these patients were treated with GCs. Generalized bone loss was related to joint damage in some studies [109, 110], but this relation disappeared after multivariate adjustment [111]. No correlation between BMD and the presence of vertebral fractures in RA patients treated with GCs was found [112].

Fracture risk in rheumatoid arthritis

In the largest epidemiological study, patients with RA were at increased risk for fractures of osteoporotic fractures (relative risk (RR) 1.5), fractures of the hip (RR 2.0), clinical vertebral fractures (RR 2.4), and fractures of the pelvis (RR 2.2) [113]. The risk of morphometric vertebral fractures was also increased [114, 115]. In some but not all studies, the risk of fractures of the humerus (RR 1.9), wrist (RR 1.2), and tibia/fibula (RR 1.3) was increased [75, 116, 117].

The etiology of increased fracture risk in RA is multifactorial and superimposed on and independent of BMD and other clinical risk factors for fractures, including the use of GCs. RA is included as an independent clinical risk factor for 10-year fracture risk calculation for major and hip fractures in the fracture risk assessment tool (FRAX) case-finding algorithm [118]. Stress fractures have been found in 0.8% of patients with RA, can be difficult to diagnose, and were related to GC use but not to BMD [119].

Fracture risk in RA was related to the duration of RA [120], the severity of disease, and its musculoskeletal consequences, such as disability, HAQ score, lack of physical activity, and impaired grip strength [120–122]. Vertebral fractures were related to disease duration and severity [69]. In the general population, fracture risk was related to serum levels of IL-6, TNF, and CRP [123] and parameters of bone resorption [124], all of which can be increased in RA. Extraskeletal risk factors that influence fracture risk include increased risk of fall rates which were related to number of swollen joints and impaired balance tests [125].

Risk predictors of bone changes in rheumatoid arthritis

Currently, the most widely used case-finding algorithm for calculating the 10-year fracture risk for major and hip fractures is the FRAX tool [118]. FRAX includes RA as a risk for fractures, independently of and superimposed on other risk factors, including BMD and use of GCs [118]. No fracture risk calculator that also includes other risk factors that are related to RA, such as disease duration and disease severity, is available. The Garvan fracture risk calculator (GFRC) can be used to calculate the 5- and 10-year fracture risk which includes the number of recent falls and the number of previous fractures but lacks RA as a risk factor [126]. Fracture risk is higher with GFRC than with FRAX in patients with recent falls [126]. In view of the increased fracture risk in patients with RA, systematic evaluation of fracture risk should be considered using FRAX, disease severity, and duration, and GFRC is helpful when patients report recent falls. Risk of low BMD is difficult to estimate in RA [90], and this suggests that bone densitometry should also be considered in fracture risk calculation in patients with active RA [127]. Many risk factors, including baseline disease severity, RF, anti-CCP, baseline bone destruction, the RANKL/OPG ratio, and CTX-I and CTX-II, have been identified for the prediction of bone erosions in RA. This pallet of predictors can now be extended with measurement of changes in periarticular bone (by DXR) and osteitis (on MRI) early in the disease [73, 81, 82]. Additional studies will be necessary to study the relation between osteitis and bone loss.

Effect of treatment on bone changes in rheumatoid arthritis

As the pathophysiology of bone loss in RA is taken into account (Figure 4), therapy should be directed at suppressing inflammation and bone resorption and restoring bone formation. No randomized placebo-controlled trials (RCTs) on the effect of treatment on fracture risk in RA are available. However, the available data suggest that control of inflammation (TNF blockade and appropriate dose of GCs), specific inhibition of bone resorption (bisphosphonates and denosumab), strontium ranelate, and restoration of the balance between bone resorption and formation (teriparatide and PTH) are candidates for such studies. Bone loss early in the disease continued despite clinical improvement and sufficient control of inflammation through treatment, indicating a disconnect between clinical inflammation and intramedullary bone loss [128]. However, these studies did not include TNF blockers, and, at that time, remission was not a realistic tool of therapy. Suppression of inflammation with TNF blockers such as infliximab and adalimumab decreased markers of bone resorption and the RANKL/OPG ratio [129], decreased osteitis, and reduced or arrested generalized (in spine and hip) bone loss [75]. Infliximab, however, did not arrest periarticular bone loss [129]. In the Behandelstrategieën voor Reumatoide Artritis (BEST) study, both bone loss at the metacarpals and radiographic joint damage were lower in patients adequately treated with combination therapy of methotrexate plus highdose prednisone or infliximab than in patients with suboptimal treatment [130].

Several pilot studies on the effect of antiresorptive drugs on bone in RA have been performed. Pamidronate reduced bone turnover in RA [131]. Zoledronate decreased the number of hand and wrist bones with erosions [132]. Denosumab strongly suppressed bone turnover and, in higher dosages than advocated for the treatment of postmenopausal ostepororotic women, prevented the occurrence of new erosions and increased BMD in the spine, hip, and hand, without an effect on joint space narrowing and without suppressing inflammation, indicating an effect on bone metabolism but not on cartilage metabolism [133–136].

The effects of GCs on bone loss and fracture risk in RA should be interpreted with caution as GCs have a dual effect on bone in RA. On the one hand, controlling inflammation with GCs strongly reduces bone loss, whereas, on the other hand, GCs enhance bone resorption, suppress bone formation, and induce osteocyte apoptosis.

Studies in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis (GIOP) included patients with RA. None of these studies had fracture prevention as a primary endpoint, and no data on the GIOP studies on fracture prevention in RA separately are available (see [137] for a recent review). RCTs in GIOP showed that bisphosphonate treatment (alendronate, risedronate, and zoledronate) and teriparatide prevented bone loss and increased BMD. Alendronate and risedronate decreased the risk of vertebral fractures versus placebo and teriparatide versus alendronate. No convincing evidence on fracture risk in GIOP for calcium and vitamin D supplements (calcitriol or alfacalcidol) is available. However, most RCTs in GIOP provided calcium and vitamin D supplements. Most guidelines, therefore, advocate calcium and vitamin D supplements, bisphosphonates, and eventually teriparatide as a second choice because of its higher cost price in the prevention of GIOP in patients at high risk, such as those with persistent disease activity, high dose of GCs, or high background risk such as menopause, age, low BMD, and the presence of clinical risk factors [138, 139].

Taken together, these data indicate that control of inflammation is able to halt bone loss and suppress osteitis in RA. Bisphosphonates are the front-line choice for fracture prevention in GIOP, but in patients with a very high fracture risk, teriparatide might be an attractive alternative. The effect of denosumab indicates that osteoclasts are the final pathway in bone erosions and local and generalized bone loss and that the bone destruction component of RA can be disconnected from inflammation by targeting RANKL.

Generalized bone loss in ankylosing spondylitis

Bone loss in the vertebrae occurs early in the disease, as shown by DXA [140] and qCT [141]. In advanced disease, the occurrence of syndesmophytes and periosteal and discal bone apposition does not allow intravertebral bone changes with DXA to be measured accurately. Combined analyses of DXA and QCT in patients with early and long-standing disease indicate that bone loss in the vertebrae occurs early in the disease and can be measured by DXA and QCT but that, in long-standing disease, DXA of the spine can be normal, in spite of further intravertebral bone loss as shown with qCT [142, 143]. As a result, in early disease, osteoporosis was found more frequently in the spine than in the hip, whereas in patients with long-standing disease, osteoporosis was more frequent in the hip [75]. Hip BMD was related to the presence of syndesmophytes and vertebral fractures, to disease duration and activity [142, 144], and to CRP [145]. Osteitis in the vertebrae precedes the development of erosions and syndesmophytes [41, 42].

Fracture risk in ankylosing spondylitis

Morphometric vertebral fractures (with a deformation of 15% or 20%) have been reported to be 10% to 30% in groups of patients with AS [146]. The odds ratios of clinical vertebral fractures were 7.7 in a retrospective population-based study [147] and 3.3 in a primary care-based nested case control study [148]. In both studies, the risk of non-vertebral fractures was not increased.

The risk of vertebral fractures is multifactorial and independent of and superimposed on other clinical risk factors [118].

Vertebral fracture risk in AS was higher in men than in women and was associated with low BMD, disease activity, and the extent of syndesmophytes [144, 149]. Vertebral fractures contributed to irreversible hyperkyphosis, which is characteristic in some patients with advanced disease with extensive syndesmophytes (bamboo spine) [150, 151].

Apart from presenting with these 'classical' vertebral fractures, patients with AS can present with vertebral fractures that are specifically reported in AS. First, erosions at the anterior corners and at the endplates of vertebrae (Andersson and Romanus lesions) result in vertebral deformities if erosions are extensive and the results of such measurements should not be considered a classical vertebral fracture (Figure 5) [75, 152]. Second, in a survey of 15,000 patients with AS, 0.4% reported clinical vertebral fractures with major neurological complications [153]. Third, owing to the stiffening of the spine by syndesmophytes, transvertebral fractures have been described [153]. Fourth, fractures can occur in the ossified connections between the vertebrae [153]. In all of these cases, CT, MRI, and eventually bone scintigraphy are helpful to identify these lesions and the extent of neurological consequences (Figure 6) [154].

Risk predictors of bone changes in ankylosing spondylitis

The diagnosis of vertebral fractures is hampered by the finding that only one out of three morphometric vertebral fractures is accompanied by clinical signs and symptoms of an acute fracture. This is probably even less in patients with AS as fractures of the vertebrae and their annexes can be easily overlooked when a flare of back pain is considered to be of inflammatory origin without taking into account the possibility of a fracture. In case of a flare of back pain, special attention, therefore, is necessary to diagnose vertebral fractures in AS, even after minimal trauma. Additional imaging (CT, MRI, and bone scintigraphy) might be necessary in patients in whom a fracture is suspected in the absence of abnormalities on conventional radiographs. On the basis of the limited data on fracture risk in AS, vertebral fractures especially should be considered in patients with a flare of back pain, persistent inflammation, long disease duration, hyperkyphosis with increased occiput-wall distance, bamboo spine, and persistent pain after trauma, even low-energy trauma. The FRAX algorithm can be used to calculate the 10-year fracture risk but cannot be used to separately calculate the risk of clinical vertebral fractures [118].

Risk factors to predict erosive sacroiliitis have been identified. These include male gender, CRP, B27, clinical symptoms, family history [155–157], and the occurrence of syndesmpophytes (such as B27, uveitis, no peripheral arthritis, prevalent syndesmophytes, and disease duration) [72, 158, 159]. Also, CTX-II has been shown to predict syndesmophytes, which could reflect cartilage destruction during enchondral new bone formation in enthesitis, including syndesmophytes [27]. These risk factors can now be extended with subchondral bone involvement (as defined by osteitis on MRI) that has been shown to predict erosive sacroiliitis [39] and the occurrence of syndesmophytes [160, 161]. To predict radiographic erosive sacroiliitis, the Assessment of Spondylo-Arthritis international Society recently developed and validated criteria that included active signs of inflammation on MRI, which are defined as active inflammatory lesions of sacroiliac joints with definite bone marrow edema/osteitis [156, 157].

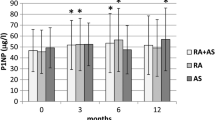

Effect of treatment on bone changes in ankylosing spondylitis

As the pathophysiology of vertebral fractures in AS is taken into account (Figure 7), therapy should be directed at suppressing inflammation, bone resorption, and bone formation. No RCTs on the effect of treatment on the risk of vertebral fractures in AS are available. In the General Practice Research Database, the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is associated with a 30% decrease in the risk of clinical vertebral fractures, but this has not been studied prospectively [75, 148]. In general, continuous use of NSAIDs, in comparison with intermittent use, and celecoxib decreased the formation of syndesmophytes [148, 162]. The mechanisms of these effects are unclear. NSAIDs inhibit bone formation, as shown in fracture healing, which is also an inflammation-driven model of increased bone formation [163, 164]. One other explanation is that pain relief can ameliorate function and decrease immobility [75]. Limited studies with bisphosphonates indicated inhibition of inflammation in AS [165]. Zoledronate did not prevent the occurrence of syndesmophytes in rats [166]. Bisphosphonates, however, can be considered in the treatment of osteoporosis in high-risk patients [167]. TNF blockade decreased osteitis, prevented bone loss, and decreased CRP and IL-6 [145, 168] but had no effect on the occurrence of syndesmophytes [169]. Taken together, these data indicate that control of inflammation is able to halt bone loss and suppress osteitis in AS but not the occurrence of syndesmophytes. Further research is needed to understand why NSAIDs could decrease fracture risk and syndesmophyte formation, why TNF blockade prevents bone loss but not syndesmophyte formation, and new ways to prevent syndesmophyte formation.

Discussion and summary

These data indicate that bone is a major target for inflammation and that bone loss and osteoporosis are common features that contribute to the increased fracture risk in RA and AS. However, the problem of bone involvement in RA and AS is more complex than in primary osteoporosis alone. The consistent finding of peri-inflammatory bone loss and osteitis in both RA and AS raises questions, besides fracture risk, about the clinical significance of bone loss.

Periarticular bone loss and osteitis coincide early in RA and AS and not only precede but also predict the occurrence of visible erosions [76]. This raises the question of the mechanism by which these anatomical coincident changes in the joints, entheses, and bone marrow occur. As described above, no direct anatomical or vascular connection between the joint cavity and bone marrow is present, but some healthy subjects can have small erosions in the MCP joints without having RA and have erosions at the entheses and vertebral cortices. In subjects with small erosions before RA or AS becomes apparent clinically, it can be assumed that, when they develop arthritis or enthesitis, the erosions allow immediate contact with bone marrow, resulting in coincident joint, enthesis, and bone marrow inflammation. Healthy subjects without such erosions could develop small erosions, resulting in measurable peri-inflammatory bone loss, before they can be identified on radiographs or MRI because of the spatial resolution of radiology and MRI and the single-plane images of radiographs. Another hypothesis is that RA and AS are primarily bone marrow diseases [170, 171], with secondary invasion of the joint via erosions created by intramedullary activated osteoclasts or via pre-existing erosions. Indeed, CD34+ bone marrow stem cells have been shown to be abnormally sensitive to TNFα to produce fibroblast-like cells [172], suggesting an underlying bone marrow stem cell abnormality in RA.

In AS, the finding of early osteitis is even more intriguing as osteitis is occurring in the vertebrae, where no synovium but periost is present at the anterior sites and discs between vertebrae. Local communication with the periost is possible by the local vascular connections or pre-existing erosions, leaving open the possibility that periost is the primary location of inflammation in AS. The same applies for the intervertebral disc, which has no direct vascular contact but can have pre-existing erosions. Whether RA and AS are initialized in the joints, enthesis, or the bone marrow is a growing field of debate [170], and such hypotheses will need much more study.

Regardless of these anatomical considerations, when the size of bone edema that can be found by MRI and the extent of early periarticular bone loss are taken into account, it seems that inflammation is as intense and extensive inside bone marrow as in the synovial joint in RA and AS and in the enthesis in AS. As bone loss and bone edema occur early in the disease, these findings indicate that bone marrow inflammation - and not just joint or enthesis inflammation - is a classical feature of early RA and AS. To what degree impaired osteoblast function is associated with loss of control of HSC and B-cell differentiation in their subendosteal niches in RA is unknown and needs further study as B-cell proliferation is a feature of RA but not of AS [173–175].

The finding that bone involvement can be disconnected from clinically detectable inflammation is quite intriguing. In RA, bone erosions can progress even when the inflammatory process is adequately controlled (that is, in clinical remission) [176], and progress of bone erosions can be halted by denosumab in spite of persistent inflammation [133–136]. In AS, the occurrence of syndesmophytes can progress in spite of suppression of inflammation by TNF blockade [160]. These findings have been described as a disconnection between inflammation and bone destruction and repair.

The correlation and eventual disconnection between osteitis and bone loss, parameters of disease activity, and erosions suggest a dual time-dependent role for the occurrence of erosions. Early in the disease process, the primary negative effect of pre-existing or newly formed erosions is the connection they create between the bone marrow and the joints, periost, and entheses. In this way, erosions contribute to local amplification of inflammation by allowing bone marrow cells to have direct local connection with extraosseous structures and creating a vicious circle of inflammation between joints, periost, entheses, and bone marrow [177]. Only in a later stage do erosions contribute to loss of function [178]. In this hypothesis, the attack of inflammation on bone by stimulating osteoclasts has far-reaching consequences. First, it would indicate that timely disease suppression and the prevention of the development of a first erosion rather than halting erosion progression should be considered a primary objective, both in RA and AS [179]. Second, periarticular bone loss and osteitis should be considered, at least theoretically, an indication for the presence of erosions, even when erosions cannot be visualized on radiographs or MRI, and periarticular bone loss and osteitis should be considered an indication for early aggressive therapy [180]. Of course, the effectiveness of antirheumatic treatment based on osteitis should be demonstrated. Third, the finding of disconnection between inflammation and bone involvement indicates that, even when inflammation is clinically under control, the degree to which bone-directed therapy is indicated should be studied in order to prevent (further) progression of erosions and syndesmophytes. In conclusion, the involvement of bone as a major target of inflammation in RA and AS raises many questions [10, 181–184], opening perspectives for further research in the understanding and treatment of the complex bone disease component of RA and AS.

Note

This article is part of the series Osteoimmunology, edited by Georg Schett. Other articles in this series can be found at http://arthritis-research.com/series/osteoimmunology

Abbreviations

- anti-CCP:

-

anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody

- AS:

-

ankylosing spondylitis

- BMD:

-

bone mineral density

- BMP:

-

bone morphogenetic protein

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- CT:

-

computed tomography

- DKK:

-

Dikkoppf

- DXA:

-

dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry

- DXR:

-

digitalized radiogrammetry

- ESR:

-

erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- FRAX:

-

fracture risk assessment tool

- GC:

-

glucocorticoid

- GFRC:

-

Garvan fracture risk calculator

- GIOP:

-

glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis

- HAQ:

-

health assessment questionnaire

- HRqCT:

-

high-resolution quantitative computer tomography

- HSC:

-

hematopoietic stem cell

- IFNγ:

-

interferon-gamma

- IL:

-

interleukin

- MCP:

-

metacarpophalangeal

- MRI:

-

magnetic resonance imaging

- NSAID:

-

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- OPG:

-

osteoprotegerin

- PTH:

-

parathyroid hormone

- qCT:

-

quantitative computer tomography

- QUS:

-

quantitative ultrasound

- RA:

-

rheumatoid arthritis

- RANK:

-

receptor activator of the nuclear factor-kappa-B

- RANKL:

-

receptor activator of the nuclear factor-kappa-B ligand

- RCT:

-

randomized placebo-controlled trial

- RF:

-

rheumatoid factor

- RR:

-

relative risk

- SpA:

-

spondylarthopathy

- TNF:

-

tumor necrosis factor.

References

Takayanagi H: Osteoimmunology and the effects of the immune system on bone. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2009, 5: 667-676. 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.217.

Fuller K, Wong B, Fox S, Choi Y, Chambers TJ: TRANCE is necessary and sufficient for osteoblast-mediated activation of bone resorption in osteoclasts. J Exp Med. 1998, 188: 997-1001. 10.1084/jem.188.5.997.

Lacey DL, Timms E, Tan HL, Kelley MJ, Dunstan CR, Burgess T, Elliott R, Colombero A, Elliott G, Scully S, Hsu H, Sullivan J, Hawkins N, Davy E, Capparelli C, Eli A, Qian YX, Kaufman S, Sarosi I, Shalhoub V, Senaldi G, Guo J, Delaney J, Boyle WJ: Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell. 1998, 93: 165-176. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81569-X.

Lorenzo J, Horowitz M, Choi Y: Osteoimmunology: interactions of the bone and immune system. Endocr Rev. 2008, 29: 403-40. 10.1210/er.2007-0038.

Lorenzo J, Choi Y, Horowitz M, Takayanagi H, Editors: Osteoimmunology. 2011, London: Academic Press, Elsevier Inc.

Kanis JA: Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: synopsis of a WHO report. WHO Study Group. Osteoporos Int. 1994, 4: 368-381. 10.1007/BF01622200.

Sommer OJ, Kladosek A, Weiler V, Czembirek H, Boeck M, Stiskal M: Rheumatoid arthritis: a practical guide to state-of-the-art imaging, image interpretation, and clinical implications. Radiographics. 2005, 25: 381-398. 10.1148/rg.252045111.

Ejbjerg B, Narvestad E, Rostrup E, Szkudlarek M, Jacobsen S, Thomsen HS, Østergaard M: Magnetic resonance imaging of wrist and finger joints in healthy subjects occasionally shows changes resembling erosions and synovitis as seen in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 50: 1097-1106. 10.1002/art.20135.

Stach CM, Bäuerle M, Englbrecht M, Kronke G, Engelke K, Manger B, Schett G: Periarticular bone structure in rheumatoid arthritis patients and healthy individuals assessed by high-resolution computed tomography. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62: 330-339.

McGonagle D, Tan AL, Moller Døhn U, Ostergaard M, Benjamin M: Microanatomic studies to define predictive factors for the topography of periarticular erosion formation in inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 60 (4): 1042-1051. 10.1002/art.24417.

Benjamin M, Toumi H, Suzuki D, Redman S, Emery P, McGonagle D: Microdamage and altered vascularity at the enthesis-bone interface provides an anatomic explanation for bone involvement in the HLA-B27-associated spondylarthritides and allied disorders. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56: 224-233. 10.1002/art.22290.

François RJ, Dhem A: Microradiographic study of the normal human vertebral body. Acta Anat (Basel). 1974, 89: 251-265. 10.1159/000144288.

Raisz LG: What marrow does to bone. N Engl J Med. 1981, 304: 1485-1486. 10.1056/NEJM198106113042410.

Colburn NT, Zaal KJ, Wang F, Tuan RS: A role for gamma/delta T cells in a mouse model of fracture healing. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 60: 1694-1703. 10.1002/art.24520.

Calvi LM, Adams GB, Weibrecht KW, Weber JM, Olson DP, Knight MC, Martin RP, Schipani E, Divieti P, Bringhurst FR, Milner LA, Kronenberg HM, Scadden DT: Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003, 425: 841-846. 10.1038/nature02040.

Frisch BJ, Porter RL, Calvi LM: Hematopoietic niche and bone meet. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2008, 2: 211-217. 10.1097/SPC.0b013e32830d5c12.

Yin T, Li L: The stem cell niches in bone. J Clin Invest. 2006, 116: 1195-1201. 10.1172/JCI28568.

Adams GB, Chabner KT, Alley IR, Olson DP, Szczepiorkowski ZM, Poznansky MC, Kos CH, Pollak MR, Brown EM, Scadden DT: Stem cell engraftment at the endosteal niche is specified by the calciumsensing receptor. Nature. 2006, 439: 599-603. 10.1038/nature04247.

Lories RJ, Luyten FP: Bone morphogenetic proteins in destructive and remodeling arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007, 9: 207-10.1186/ar2135.

Diarra D, Stolina M, Polzer K, Zwerina J, Ominsky MS, Dwyer D, Korb A, Smolen J, Hoffmann M, Scheinecker C, van der Heide D, Landewe R, Lacey D, Richards WG, Schett G: Dickkopf-1 is a master regulator of joint remodeling. Nat Med. 2007, 13: 156-163. 10.1038/nm1538.

Appel H, Ruiz-Heiland G, Listing J, Zwerina J, Herrmann M, Mueller R, Haibel H, Baraliakos X, Hempfing A, Rudwaleit M, Sieper J, Schett G: Altered skeletal expression of sclerostin and its link to radiographic progression in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 60: 3257-3262. 10.1002/art.24888.

Goldring SR, Schett G: The role of the immune system in bone loss of inflammatory arthritis. Osteoimmunology. Edited by: Lorenzo J, Choi Y, Horowitz M, Takayanagi H. 2011, London: Academic Press, Elsevier Inc., 301-324.

Herman S, Müller RB, Kronke G, Zwerina J, Redlich K, Hueber AJ, Gelse H, Neumann E, Müller-Ladner U, Schett G: Induction of osteoclast-associated receptor, a key osteoclast costimulation molecule, in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 58: 3041-3050. 10.1002/art.23943.

Nemeth K, Schoppet M, Al-Fakhri N, Helas S, Jessberger R, Hofbauer LC, Goettsch C: The role of osteoclast-associated receptor in osteoimmunology. J Immunol. 2011, 186: 13-18. 10.4049/jimmunol.1002483.

Daoussis D, Liossis SN, Solomou EE, Tsanaktsi A, Bounia K, Karampetsou M, Yiannopoulos G, Andonopoulos AP: Evidence that Dkk-1 is dysfunctional in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62: 150-158. 10.1002/art.27231.

Chen HA, Chen CH, Lin YJ, Chen PC, Chen WS, Lu CL, Chou CT: Association of bone morphogenetic proteins with spinal fusion in ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 2010, 37: 2126-2132. 10.3899/jrheum.100200.

Vosse D, Landewé R, Garnero P, van der Heijde D, van der Linden S, Geusens P: Association of markers of bone- and cartilage-degradation with radiological changes at baseline and after 2 years follow-up in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008, 47: 1219-1222. 10.1093/rheumatology/ken148.

Braun J, Baraliakos X: Imaging of axial spondyloarthritis including ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011, 70 (Suppl 1): i97-103. 10.1136/ard.2010.140541.

Teitelbaum SL: Postmenopausal osteoporosis, T cells, and immune dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004, 101: 16711-16712. 10.1073/pnas.0407335101.

Leisen JC, Duncan H, Riddle JM, Pitchford WC: The erosive front: a topographic study of the junction between the pannus and the subchondral plate in the macerated rheumatoid metacarpal head. J Rheumatol. 1988, 15: 17-22.

Pettit AR, Walsh NC, Manning C, Goldring SR, Gravallese EM: RANKL protein is expressed at the pannus-bone interface at sites of articular bone erosion in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006, 45: 1068-1076. 10.1093/rheumatology/kel045.

Bywaters EG: The early radiological signs of rheumatoid arthritis. Bull Rheum Dis. 1960, 11: 231-234.

Jimenez-Boj E, Nöbauer-Huhmann I, Hanslik-Schnabel B, Dorotka R, Wanivenhaus AH, Kainberger F, Trattnig S, Axmann R, Tsuji W, Hermann S, Smolen J, Schett G: Bone erosions and bone marrow edema as defined by magnetic resonance imaging reflect true bone marrow inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56: 1118-1124. 10.1002/art.22496.

Reid DM, Kennedy NS, Smith MA, Tothill P, Nuki G: Total body calcium in rheumatoid arthritis: effects of disease activity and corticosteroid treatment. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1982, 285: 330-332. 10.1136/bmj.285.6338.330.

Engfeldt B, Romanus R, Yden S: Histological studies of pelvo-spondylitis ossificans (ankylosing spondylitis) correlated with clinical and radiological findings. Ann Rheum Dis. 1954, 13: 219-228. 10.1136/ard.13.3.219.

François RJ, Gardner DL, Degrave EJ, Bywaters EG: Histopathologic evidence that sacroiliitis in ankylosing spondylitis is not merely enthesitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000, 43: 2011-2024. 10.1002/1529-0131(200009)43:9<2011::AID-ANR12>3.0.CO;2-Y.

Aufdermaur M: Pathogenesis of square bodies in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1989, 48: 628-631. 10.1136/ard.48.8.628.

Rudwaleit M, Jurik AG, Hermann KG, Landewé R, van der Heijde D, Baraliakos X, Marzo-Ortega H, Ostergaard M, Braun J, Sieper J: Defining active sacroiliitis on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for classification of axial spondyloarthritis: a consensual approach by the ASAS/OMERACT MRI group. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009, 68: 1520-1527. 10.1136/ard.2009.110767.

Zochling J, Baraliakos X, Hermann KG, Braun J: Magnetic resonance imaging in ankylosing spondylitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007, 19: 346-352. 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32816a938c.

Baraliakos X, Landewé R, Hermann KG, Listing J, Golder W, Brandt J, Rudwaleit M, Bollow M, Sieper J, van der Heijde D, Braun J: Inflammation in ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic description of the extent and frequency of acute spinal changes using magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005, 4: 730-734.

Maksymowych WP: MRI in ankylosing spondylitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009, 21: 313-317. 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32832af481.

Maksymowych WP: Progress in spondylarthritis. Spondyloarthritis: lessons from imaging. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009, 11: 222-10.1186/ar2665.

Cruickshank B: Lesions of cartilaginous joints in ankylosing spondylitis. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1956, 71: 73-84. 10.1002/path.1700710111.

Appel H, Loddenkemper C, Grozdanovic Z, Ebhardt H, Dreimann M, Hempfing A, Stein H, Metz-Stavenhagen P, Rudwaleit M, Sieper J: Correlation of histopathological findings and magnetic resonance imaging in the spine of patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006, 8: R143-10.1186/ar2035.

Appel H, Kuhne M, Spiekermann S, Ebhardt H, Grozdanovic Z, Köhler D, Dreimann M, Hempfing A, Rudwaleit M, Stein H, Metz-Stavenhagen P, Sieper J, Loddenkemper C: Immunohistologic analysis of zygapophyseal joints in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54: 2845-2851. 10.1002/art.22060.

Benjamin M, McGonagle D: The enthesis organ concept and its relevance to the spondyloarthropathies. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009, 649: 57-70. 10.1007/978-1-4419-0298-6_4.

McGonagle D, Gibbon W, Emery P: Classification of inflammatory arthritis by enthesitis. Lancet. 1998, 352: 1137-1140. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)12004-9.

Walsh NC, Reinwald S, Manning CA, Condon KW, Iwata K, Burr DB, Gravallese EM: Osteoblast function is compromised at sites of focal bone erosion in inflammatory arthritis. J Bone Miner Res. 2009, 24: 1572-1585. 10.1359/jbmr.090320.

Møller Døhn U, Boonen A, Hetland ML, Hansen MS, Knudsen LS, Hansen A, Madsen OR, Hasselquist M, Møller JM, Østergaard M: Erosive progression is minimal, but erosion healing rare, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with adalimumab. A 1 year investigator-initiated follow-up study using high-resolution computed tomography as the primary outcome measure. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009, 68: 1585-1590. 10.1136/ard.2008.097048.

François RJ: Microradiographic study of the intervertebral bridges in ankylosing spondylitis and in the normal sacrum. Ann Rheum Dis. 1965, 24: 481-489. 10.1136/ard.24.5.481.

Sambrook PN, Ansell BM, Foster S, Gumpel JM, Hesp R, Reeve J, Zanelli JM: Bone turnover in early rheumatoid arthritis. 1. Biochemical and kinetic indexes. Ann Rheum Dis. 1985, 44: 575-579. 10.1136/ard.44.9.575.

Garnero P, Delmas PD: Noninvasive techniques for assessing skeletal changes in inflammatory arthritis: bone biomarkers. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004, 16: 428-434. 10.1097/01.moo.0000127830.72761.00.

Geusens PP, Landewé RB, Garnero P, Chen D, Dunstan CR, Lems WF, Stinissen P, van der Heijde DM, van der Linden S, Boers M: The ratio of circulating osteoprotegerin to RANKL in early rheumatoid arthritis predicts later joint destruction. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54: 1772-1777. 10.1002/art.21896.

van Tuyl LH, Voskuyl AE, Boers M, Geusens P, Landewé RB, Dijkmans BA, Lems WF: Baseline RANKL:OPG ratio and markers of bone and cartilage degradation predict annual radiological progression over 11 years in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010, 69: 1623-1628. 10.1136/ard.2009.121764.

Hall GM, Spector TD, Delmas PD: Markers of bone metabolism in postmenopausal women with rheumatoid arthritis. Effects of corticosteroids and hormone replacement therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 1995, 38: 902-906. 10.1002/art.1780380705.

Deodhar AA, Woolf AD: Bone mass measurement and bone metabolism in rheumatoid arthritis: a review. Br J Rheumatol. 1996, 35: 309-322. 10.1093/rheumatology/35.4.309.

El Maghraoui A, Borderie D, Cherruau B, Edouard R, Dougados M, Roux C: Osteoporosis, body composition, and bone turnover in ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 1999, 26: 2205-2209.

MacDonald AG, Birkinshaw G, Durham B, Bucknall RC, Fraser WD: Biochemical markers of bone turnover in seronegative spondylarthropathy: relationship to disease activity. Br J Rheumatol. 1997, 36: 50-53. 10.1093/rheumatology/36.1.50.

Stupphann D, Rauner M, Krenbek D, Patsch J, Pirker T, Muschitz C, Resch H, Pietschmann P: Intracellular and surface RANKL are differentially regulated in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol Int. 2008, 28: 987-993. 10.1007/s00296-008-0567-y.

Franck H, Meurer T, Hofbauer LC: Evaluation of bone mineral density, hormones, biochemical markers of bone metabolism, and osteoprotegerin serum levels in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 2004, 31: 2236-2241.

Appel H, Maier R, Loddenkemper C, Kayser R, Meier O, Hempfing A, Sieper J: Immunohistochemical analysis of osteoblasts in zygapophyseal joints of patients with ankylosing spondylitis reveal repair mechanisms similar to osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2010, 37: 823-828. 10.3899/jrheum.090986.

Vandooren B, Cantaert T, Noordenbos T, Tak PP, Baeten D: The abundant synovial expression of the RANK/RANKL/Osteoprotegerin system in peripheral spondylarthritis is partially disconnected from inflammation. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 58: 718-729. 10.1002/art.23290.

Arends S, Spoorenberg A, Bruyn GA, Houtman PM, Leijsma MK, Kallenberg CG, Brouwer E, van der Veer E: The relation between bone mineral density, bone turnover markers, and vitamin D status in ankylosing spondylitis patients with active disease: a cross-sectional analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2011, 22: 1431-1439. 10.1007/s00198-010-1338-7.

Njeh CF, Genant HK: Bone loss. Quantitative imaging techniques for assessing bone mass in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. 2000, 2: 446-50. 10.1186/ar126.

Rosholm A, Hyldstrup L, Backsgaard L, Grunkin M, Thodberg HH: Estimation of bone mineral density by digital X-ray radiogrammetry: theoretical background and clinical testing. Osteoporos Int. 2001, 12: 961-969. 10.1007/s001980170026.

Deodhar AA, Brabyn J, Jones PW, Davis MJ, Woolf AD: Measurement of hand bone mineral content by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry: development of the method, and its application in normal volunteers and in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994, 53: 685-690. 10.1136/ard.53.10.685.

Böttcher J, Pfeil A, Mentzel H, Kramer A, Schäfer ML, Lehmann G, Eidner T, Petrovitch A, Malich A, Hein G, Kaiser WA: Peripheral bone status in rheumatoid arthritis evaluated by digital X-ray radiogrammetry and compared with multisite quantitative ultrasound. Calcif Tissue Int. 2006, 78: 25-34. 10.1007/s00223-005-0175-8.

Lespessailles E, Gadois C, Lemineur G, Do-Huu JP, Benhamou L: Bone texture analysis on direct digital radiographic images: precision study and relationship with bone mineral density at the oscalcis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2007, 80: 97-102. 10.1007/s00223-006-0216-y.

El Maghraoui A, Rezqi A, Mounach A, Achemlal L, Bezza A, Ghozlani I: Prevalence and risk factors of vertebral fractures in women with rheumatoid arthritis using vertebral fracture assessment. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010, 49: 1303-1310. 10.1093/rheumatology/keq084.

Johnell O, Kanis JA, Oden A, Johansson H, De Laet C, Delmas P, Eisman JA, Fujiwara S, Kroger H, Mellstrom D, Meunier PJ, Melton LJ, O'Neill T, Pols H, Reeve J, Silman A, Tenenhouse A: Predictive value of BMD for hip and other fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2005, 20: 1185-1194. 10.1359/JBMR.050304. Erratum in: J Bone Miner Res 2007, 22:774.

Baraliakos X, Hermann KG, Landewé R, Listing J, Golder W, Brandt J, Rudwaleit M, Bollow M, Sieper J, van der Heijde D, Braun J: Assessment of acute spinal infl ammation in patients with ankylosing spondylitis by magnetic resonance imaging: a comparison between contrast enhanced T1 and short tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequences. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005, 64: 1141-1144. 10.1136/ard.2004.031609.

Baraliakos X, Listing J, Rudwaleit M, Haibel H, Brandt J, Sieper J, Braun J: Progression of radiographic damage in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: defining the central role of syndesmophytes. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007, 66: 910-915. 10.1136/ard.2006.066415.

Fouque-Aubert A, Chapurlat R, Miossec P, Delmas PD: A comparative review of the different techniques to assess hand bone damage in rheumatoid arthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2010, 77: 212-217. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2009.08.009.

Dihlman W: Joints and Vertebral Connections. 1985, New York: Thieme Inc.

Roux C: Osteoporosis in inflammatory joint diseases. Osteoporos Int. 2011, 22: 421-433. 10.1007/s00198-010-1319-x.

Hoff M, Haugeberg G: Using hand bone measurements to assess progression of rheumatoid arthritis. Therapeutic Advances in Musculoskeletal Disease. 2010, 79-88.

Alenfeld FE, Diessel E, Brezger M, Sieper J, Felsenberg D, Braun J: Detailed analyses of periarticular osteoporosis in rheumatoid arthritis. Osteoporos Int. 2000, 11: 400-407. 10.1007/s001980070106.

Sambrook PN, Ansell BM, Foster S, Gumpel JM, Hesp R, Reeve J: Bone turnover in early rheumatoid arthritis. 2. Longitudinal bone density studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 1985, 44: 580-584. 10.1136/ard.44.9.580.

Laan RF, Buijs WC, van Erning LJ, Lemmens JA, Corstens FH, Ruijs SH, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL: Differential effects of glucocorticoids on cortical appendicular and cortical vertebral bone mineral content. Calcif Tissue Int. 1993, 52: 5-9. 10.1007/BF00675619.

Inaba M, Nagata M, Goto H, Kumeda Y, Kobayashi K, Nakatsuka K, Miki T, Yamada S, Ishimura E, Nishizawa Y: Preferential reductions of paraarticular trabecular bone component in ultradistal radius and of calcaneus ultrasonography in early-stage rheumatoid arthritis. Osteoporos Int. 2003, 14: 683-687. 10.1007/s00198-003-1427-y.

Hoff M, Haugeberg G, Odegård S, Syversen S, Landewé R, van der Heijde D, Kvien TK: Cortical hand bone loss after 1 year in early rheumatoid arthritis predicts radiographic hand joint damage at 5-year and 10-year follow-up. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009, 68: 324-329. 10.1136/ard.2007.085985.

Haugeberg G, Green MJ, Quinn MA, Marzo-Ortega H, Proudman S, Karim Z, Wakefield RJ, Conaghan PG, Stewart S, Emery P: Hand bone loss in early undifferentiated arthritis: evaluating bone mineral density loss before the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006, 65: 736-740. 10.1136/ard.2005.043869.

Bøyesen P, Hoff M, Odegård S, Haugeberg G, Syversen SW, Gaarder PI, Okkenhaug C, Kvien TK: Antibodies to cyclic citrullinated protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate predict hand bone loss in patients with rheumatoid arthritis of short duration: a longitudinal study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009, 11: R103-10.1186/ar2749.

Jawaid WB, Crosbie D, Shotton J, Reid DM, Stewart A: Use of digital x ray radiogrammetry in the assessment of joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006, 65: 459-464. 10.1136/ard.2005.039792.

Haugeberg G, Lodder MC, Lems WF, Uhlig T, Ørstavik RE, Dijkmans BA, Kvien TK, Woolf AD: Hand cortical bone mass and its associations with radiographic joint damage and fractures in 50-70 year old female patients with rheumatoid arthritis: cross sectional Oslo-Truro-Amsterdam (OSTRA) collaborative study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004, 63: 1331-1334. 10.1136/ard.2003.015065.

Bouxsein ML, Palermo L, Yeung C, Black DM: Digital X-ray radiogrammetry predicts hip, wrist and vertebral fracture risk in elderly women: a prospective analysis from the study of osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2002, 13: 358-365. 10.1007/s001980200040.

McQueen FM, Dalbeth N: Predicting joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis using MRI scanning. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009, 11: 124-10.1186/ar2778.

Bøyesen P, Haavardsholm EA, Ostergaard M, van der Heijde D, Sesseng S, Kvien TK: MRI in early rheumatoid arthritis: synovitis and bone marrow oedema are independent predictors of subsequent radiographic progression. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011, 70: 428-433. 10.1136/ard.2009.123950.

McQueen FM, Stewart N, Crabbe J, Robinson E, Yeoman S, Tan PL, McLean L: Magnetic resonance imaging of the wrist in early rheumatoid arthritis reveals a high prevalence of erosions at four months after symptom onset. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998, 57: 350-356. 10.1136/ard.57.6.350.

McQueen FM, Benton N, Perry D, Crabbe J, Robinson E, Yeoman S, McLean L, Stewart N: Bone edema scored on magnetic resonance imaging scans of the dominant carpus at presentation predicts radiographic joint damage of the hands and feet six years later in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003, 48: 1814-1827. 10.1002/art.11162.

Hodgson RJ, O'Connor P, Moots R: MRI of rheumatoid arthritis image quantitation for the assessment of disease activity, progression and response to therapy. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008, 47: 13-21. 10.1093/rheumatology/kem250.

Bird P, Conaghan P, Ejbjerg B, McQueen F, Lassere M, Peterfy C, Edmonds J, Shnier R, O'Connor P, Haavardsholm E, Emery P, Genant H, Østergaard M: The development of the EULAR-OMERACT rheumatoid arthritis MRI reference image atlas. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005, 64 (Suppl 1): i8-10.

Tamai M, Kawakami A, Uetani M, Takao S, Arima K, Iwamoto N, Fujikawa K, Aramaki T, Kawashiri SY, Ichinose K, Kamachi M, Nakamura H, Origuchi T, Ida H, Aoyagi K, Eguchi K: A prediction rule for disease outcome in patients with undifferentiated arthritis using magnetic resonance imaging of the wrists and finger joints and serologic autoantibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 61: 772-778. 10.1002/art.24711.

Hetland ML, Ejbjerg B, Hørslev-Petersen K, Jacobsen S, Vestergaard A, Jurik AG, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Junker P, Lottenburger T, Hansen I, Andersen LS, Tarp U, Skjødt H, Pedersen JK, Majgaard O, Svendsen AJ, Ellingsen T, Lindegaard H, Christensen AF, Vallø J, Torfing T, Narvestad E, Thomsen HS, Ostergaard M, CIMESTRA study group: MRI bone oedema is the strongest predictor of subsequent radiographic progression in early rheumatoid arthritis. Results from a 2-year randomised controlled trial (CIMESTRA). Ann Rheum Dis. 2009, 68: 384-390. 10.1136/ard.2008.088245.

McQueen FM, Gao A, Ostergaard M, King A, Shalley G, Robinson E, Doyle A, Clark B, Dalbeth N: High-grade MRI bone oedema is common within the surgical field in rheumatoid arthritis patients undergoing joint replacement and is associated with osteitis in subchondral bone. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007, 66: 1581-1587. 10.1136/ard.2007.070326.

Dalbeth N, Smith T, Gray S, Doyle A, Antill P, Lobo M, Robinson E, King A, Cornish J, Shalley G, Gao A, McQueen FM: Cellular characterisation of magnetic resonance imaging bone oedema in rheumatoid arthritis; implications for pathogenesis of erosive disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009, 68: 279-282. 10.1136/ard.2008.096024.

Oelzner P, Schwabe A, Lehmann G, Eidner T, Franke S, Wolf G, Hein G: Significance of risk factors for osteoporosis is dependent on gender and menopause in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2008, 28: 1143-1150. 10.1007/s00296-008-0576-x.

Lane NE, Pressman AR, Star VL, Cummings SR, Nevitt MC: Rheumatoid arthritis and bone mineral density in elderly women. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. J Bone Miner Res. 1995, 10: 257-263.

Kröger H, Honkanen R, Saarikoski S, Alhava E: Decreased axial bone mineral density in perimenopausal women with rheumatoid arthritis - a population based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994, 53: 18-23. 10.1136/ard.53.1.18.

Haugeberg G, Uhlig T, Falch JA, Halse JI, Kvien TK: Bone mineral density and frequency of osteoporosis in female patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from 394 patients in the Oslo County Rheumatoid Arthritis register. Arthritis Rheum. 2000, 43: 522-30. 10.1002/1529-0131(200003)43:3<522::AID-ANR7>3.0.CO;2-Y.

Bhalla AK, Shenstone B: Bone densitometry measurements in early inflammatory disease. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1992, 6: 405-414. 10.1016/S0950-3579(05)80182-7.

Hanley DA, Brown JP, Tenenhouse A, Olszynski WP, Ioannidis G, Berger C, Prior JC, Pickard L, Murray TM, Anastassiades T, Kirkland S, Joyce C, Joseph L, Papaioannou A, Jackson SA, Poliquin S, Adachi JD, Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study Research Group: Associations among disease conditions, bone mineral density, and prevalent vertebral deformities in men and women 50 years of age and older: cross-sectional results from the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2003, 18: 784-790. 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.4.784.

Güler-Yüksel M, Bijsterbosch J, Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Ronday HK, Peeters AJ, de Jonge-Bok JM, Breedveld FC, Dijkmans BA, Allaart CF, Lems WF: Bone mineral density in patients with recently diagnosed, active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007, 66: 1508-1512. 10.1136/ard.2007.070839.

Guler H, Turhanoglu AD, Ozer B, Ozer C, Balci A: The relationship between anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide and bone mineral density and radiographic damage in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2008, 37: 337-342. 10.1080/03009740801998812.

Wijbrandts CA, Klaasen R, Dijkgraaf MG, Gerlag DM, van Eck-Smit BL, Tak PP: Bone mineral density in rheumatoid arthritis patients 1 year after adalimumab therapy: arrest of bone loss. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009, 68: 373-376. 10.1136/ard.2008.091611.

Forslind K, Keller C, Svensson B, Hafström I, BARFOT Study Group: Reduced bone mineral density in early rheumatoid arthritis is associated with radiological joint damage at baseline and after 2 years in women. J Rheumatol. 2003, 30: 2590-2596.

Gough AK, Lilley J, Eyre S, Holder RL, Emery P: Generalised bone loss in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 1994, 344: 23-27. 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)91049-9.

Kroot EJ, Nieuwenhuizen MG, de Waal Malefijt MC, van Riel PL, Pasker-de Jong PC, Laan RF: Change in bone mineral density in patients with rheumatoid arthritis during the first decade of the disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2001, 44: 1254-1260. 10.1002/1529-0131(200106)44:6<1254::AID-ART216>3.0.CO;2-G.

Lodder MC, Haugeberg G, Lems WF, Uhlig T, Orstavik RE, Kostense PJ, Dijkmans BA, Kvien TK, Woolf AD, Oslo-Truro-Amsterdam (OSTRA) Collaborative Study: Radiographic damage associated with low bone mineral density and vertebral deformities in rheumatoid arthritis: the Oslo-Truro-Amsterdam (OSTRA) collaborative study. Arthritis Rheum. 2003, 49: 209-215. 10.1002/art.10996.

Lodder MC, de Jong Z, Kostense PJ, Molenaar ET, Staal K, Voskuyl AE, Hazes JM, Dijkmans BA, Lems WF: Bone mineral density in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: relation between disease severity and low bone mineral density. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004, 63: 1576-1580. 10.1136/ard.2003.016253.

Solomon DH, Finkelstein JS, Shadick N, LeBoff MS, Winalski CS, Stedman M, Glass R, Brookhart MA, Weinblatt ME, Gravallese EM: The relationship between focal erosions and generalized osteoporosis in postmenopausal women with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 60: 1624-1631. 10.1002/art.24551.

Peel NF, Moore DJ, Barrington NA, Bax DE, Eastell R: Risk of vertebral fracture and relationship to bone mineral density in steroid treated rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995, 54: 801-806. 10.1136/ard.54.10.801.

van Staa TP, Geusens P, Bijlsma JW, Leufkens HG, Cooper C: Clinical assessment of the long-term risk of fracture in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54: 3104-3112. 10.1002/art.22117.

Vis M, Haavardsholm EA, Bøyesen P, Haugeberg G, Uhlig T, Hoff M, Woolf A, Dijkmans B, Lems W, Kvien TK: High incidence of vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in the OSTRA cohort study: a 5-year follow-up study in postmenopausal women with rheumatoid arthritis. Osteoporos Int. 2011

Ghazi M, Kolta S, Briot K, Fechtenbaum J, Paternotte S, Roux C: Prevalence of vertebral fractures in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: revisiting the role of glucocorticoids. Osteoporos Int. 2011

Kim SY, Schneeweiss S, Liu J, Daniel GW, Chang CL, Garneau K, Solomon DH: Risk of osteoporotic fracture in a large population-based cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010, 12: R154-10.1186/ar3107.

Sinigaglia L, Varenna M, Girasole G, Bianchi G: Epidemiology of osteoporosis in rheumatic diseases. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2006, 32: 631-658. 10.1016/j.rdc.2006.07.002.

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Johansson H, McCloskey E: FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporos Int. 2008, 19: 385-397. 10.1007/s00198-007-0543-5.

Kay LJ, Holland TM, Platt PN: Stress fractures in rheumatoid arthritis: a case series and case-control study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004, 63: 1690-1692. 10.1136/ard.2003.010322.

Michel BA, Bloch DA, Wolfe F, Fries JF: Fractures in rheumatoid arthritis: an evaluation of associated risk factors. J Rheumatol. 1993, 20: 1666-1669.

Coulson KA, Reed G, Gilliam BE, Kremer JM, Pepmueller PH: Factors influencing fracture risk, T score, and management of osteoporosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America (CORRONA) registry. J Clin Rheumatol. 2009, 15: 155-160. 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3181a5679d.

Haugeberg G, Ørstavik RE, Uhlig T, Falch JA, Halse JI, Kvien TK: Clinical decision rules in rheumatoid arthritis: do they identify patients at high risk for osteoporosis? Testing clinical criteria in a population based cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis recruited from the Oslo Rheumatoid Arthritis Register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002, 61: 1085-1089. 10.1136/ard.61.12.1085.

Cauley JA, Danielson ME, Boudreau RM, Forrest KY, Zmuda JM, Pahor M, Tylavsky FA, Cummings SR, Harris TB, Newman AB, for the Health ABC Study: Inflammatory markers and incident fracture risk in older men and women: the Health Aging and Body Composition Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2007, 22: 1088-1095. 10.1359/jbmr.070409.

Garnero P, Hausherr E, Chapuy MC, Marcelli C, Grandjean H, Muller C, Cormier C, Bréart G, Meunier PJ, Delmas PD: Markers of bone resorption predict hip fracture in elderly women: the EPIDOS Prospective Study. J Bone Miner Res. 1996, 11: 1531-1538.

Hayashibara M, Hagino H, Katagiri H, Okano T, Okada J, Teshima R: Incidence and risk factors of falling in ambulatory patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective 1-year study. Osteoporos Int. 2010, 21: 1825-1833. 10.1007/s00198-009-1150-4.

van den Bergh JP, van Geel TA, Lems WF, Geusens PP: Assessment of individual fracture risk: FRAX and beyond. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2010, 8: 131-137. 10.1007/s11914-010-0022-3.

Brand C, Lowe A, Hall S: The utility of clinical decision tools for diagnosing osteoporosis in postmenopausal women with rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008, 9: 13-10.1186/1471-2474-9-13.

Deodhar AA, Brabyn J, Jones PW, Davis MJ, Woolf AD: Longitudinal study of hand bone densitometry in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995, 38: 1204-1210. 10.1002/art.1780380905.

Vis M, Havaardsholm EA, Haugeberg G, Uhlig T, Voskuyl AE, van de Stadt RJ, Dijkmans BA, Woolf AD, Kvien TK, Lems WF: Evaluation of bone mineral density, bone metabolism, osteoprotegerin and receptor activator of the NFkappaB ligand serum levels during treatment with infliximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006, 65: 1495-1499. 10.1136/ard.2005.044198.

Güler-Yüksel M, Bijsterbosch J, Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Hulsmans HM, de Beus WM, Han KH, Breedveld FC, Dijkmans BA, Allaart CF, Lems WF: Changes in bone mineral density in patients with recent onset, active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008, 67: 823-828. 10.1136/ard.2007.073817.

Lodder MC, Van Pelt PA, Lems WF, Kostense PJ, Koks CH, Dijkmans BA: Effects of high dose IV pamidronate on disease activity and bone metabolism in patients with active RA: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2003, 30: 2080-2081.

Jarrett SJ, Conaghan PG, Sloan VS, Papanastasiou P, Ortmann CE, O'Connor PJ, Grainger AJ, Emery P: Preliminary evidence for a structural benefit of the new bisphosphonate zoledronic acid in early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54: 1410-1414. 10.1002/art.21824.

Cohen SB, Dore RK, Lane NE, Ory PA, Peterfy CG, Sharp JT, van der Heijde D, Zhou L, Tsuji W, Newmark R, Denosumab Rheumatoid Arthritis Study Group: Denosumab treatment effects on structural damage, bone mineral density, and bone turnover in rheumatoid arthritis: a twelve-month, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 58: 1299-1309. 10.1002/art.23417.

Dore RK, Cohen SB, Lane NE, Palmer W, Shergy W, Zhou L, Wang H, Tsuji W, Newmark R, Denosumab RA Study Group: Effects of denosumab on bone mineral density and bone turnover in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving concurrent glucocorticoids or bisphosphonates. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010, 69: 872-875. 10.1136/ard.2009.112920.

Sharp JT, Tsuji W, Ory P, Harper-Barek C, Wang H, Newmark R: Denosumab prevents metacarpal shaft cortical bone loss in patients with erosive rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010, 62: 537-544. 10.1002/acr.20172.

Deodhar A, Dore RK, Mandel D, Schechtman J, Shergy W, Trapp R, Ory PA, Peterfy CG, Fuerst T, Wang H, Zhou L, Tsuji W, Newmark R: Denosumabmediated increase in hand bone mineral density associated with decreased progression of bone erosion in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010, 62: 569-574. 10.1002/acr.20004.

Compston J: Management of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010, 6: 82-88. 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.259.

Geusens PP, de Nijs RN, Lems WF, Laan RF, Struijs A, van Staa TP, Bijlsma JW: Prevention of glucocorticoid osteoporosis: a consensus document of the Dutch Society for Rheumatology. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004, 63: 324-325. 10.1136/ard.2003.008060.

Geusens PP: Review of guidelines for testing and treatment of osteoporosis. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2003, 1: 59-65. 10.1007/s11914-003-0010-y.

Will R, Palmer R, Bhalla AK, Ring F, Calin A: Osteoporosis in early ankylosing spondylitis: a primary pathological event?. Lancet. 1989, 2: 1483-1485.

Lee YS, Schlotzhauer T, Ott SM, van Vollenhoven RF, Hunter J, Shapiro J, Marcus R, McGuire JL: Skeletal status of men with early and late ankylosing spondylitis. Am J Med. 1997, 103: 233-241. 10.1016/S0002-9343(97)00143-5.

Karberg K, Zochling J, Sieper J, Felsenberg D, Braun J: Bone loss is detected more frequently in patients with ankylosing spondylitis with syndesmophytes. J Rheumatol. 2005, 32: 1290-1298.

Lange U, Kluge A, Strunk J, Teichmann J, Bachmann G: Ankylosing spondylitis and bone mineral density--what is the ideal tool for measurement?. Rheumatol Int. 2005, 26: 115-120. 10.1007/s00296-004-0515-4.

Ghozlani I, Ghazi M, Nouijai A, Mounach A, Rezqi A, Achemlal L, Bezza A, El Maghraoui A: Prevalence and risk factors of osteoporosis and vertebral fractures in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Bone. 2009, 44: 772-776. 10.1016/j.bone.2008.12.028.

Maillefert JF, Aho LS, El Maghraoui A, Dougados M, Roux C: Changes in bone density in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a two-year follow-up study. Osteoporos Int. 2001, 12: 605-609. 10.1007/s001980170084.

El Maghraoui A: Osteoporosis and ankylosing spondylitis. Joint Bone Spine. 2004, 71: 291-295. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2003.06.002.