Abstract

Inflammatory arthritides are commonly characterized by localized and generalized bone loss. Localized bone loss in the form of joint erosions and periarticular osteopenia is a hallmark of rheumatoid arthritis, the prototype of inflammatory arthritis. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL)-dependent osteoclast activation by inflammatory cells and subsequent bone loss. In this article, we review the pathogenesis of inflammatory bone loss and explore the possible therapeutic interventions to prevent it.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bone loss is a common feature of various inflammatory arthritides. Localized bone loss in the form of bone erosions and periarticular osteopenia constitutes an important radiographic criterion for the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). In addition, generalized bone loss has been demonstrated in RA, systemic lupus erythematosus, and ankylosing spondylitis in several observational and some longitudinal studies using markers of bone turnover, bone histomorphometry, and bone densitometry [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Laboratory-based studies have identified novel pathways that link inflammatory mediators with localized bone loss in these diseases. These studies have provided an insight into the disease pathogenesis and have created new paradigms for treatment that now await testing in clinical trials.

Bone remodeling

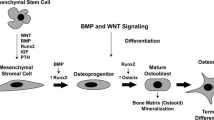

Throughout life, normal skeletal maintenance occurs by a tightly coupled process of bone remodeling. It consists of a sequential process of bone resorption by osteoclasts followed by deposition of new bone by osteoblasts. The osteoclast is a polykaryocyte formed by the fusion of mononuclear cells derived from hematopoietic bone marrow, whereas the osteoblast and its progenitor cells are derived from mesenchymal cells. The differentiation of myeloid progenitor cells into committed osteoclast lineage is characterized by the appearance of the mRNA and protein for vitronectin receptor (αvβ3), cathepsin K, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase, and calcitonin receptor [8,9]. The appearance of this receptor is followed closely by the acquisition of bone-resorbing capacity, and the number of cells positive for calcitonin receptor correlate strongly (r = 0.96) with bone resorption in cell cultures [10]. This process of osteoclastogenesis requires the presence of receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL; also known as OPGL, TRANCE, ODF, and SOFA) and the permissive factor, macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) secreted by the local osteoblast/stromal cells. RANKL binds to its receptor RANK expressed on the surface of osteoclast precursor cells and stimulates their differentiation into mature osteoclasts [11]. The osteoblast/stromal cells also secrete osteoprotegerin (OPG; also known as OCIF, TR-1, FDCR-1, and TNFRSF-11B), a soluble decoy receptor protein that binds to RANKL and prevents its binding to RANK on the preosteoclast cells. The biologic effects of OPG are, therefore, the opposite of those of RANKL, i.e. OPG inhibits osteoclastogenesis and osteoclast function and promotes osteoclast apoptosis [12] (see Fig. 1). Considerable confusion and redundancy in the naming of these three molecules led the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research to form a special committee to develop a standard nomenclature. The committee recommended naming the membrane receptor 'RANK', the receptor ligand 'RANKL', and the decoy receptor 'OPG' [13].

Osteoclastogenesis. Osteoclasts are derived from bone marrow cells, and RANKL-OPG derived from bone or synovium has a significant effect in their differentiation, activation, and survival. CTR = calcitonin receptor; M-CSF = macrophage colony-stimulating factor; OB = osteoblast; OC = osteoclast; OPG = osteoprotegerin; RANKL = receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand; TRAP = tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase.

The production and activity of both RANKL and OPG are influenced by several cytokines, inflammatory mediators, and calcitropic hormones that 'converge' onto these proteins (see Fig. 2). The net RANKL/OPG balance determines the differentiation, activation, and survival of osteoclasts, which in turn determine bone loss [14].

Various proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines converge on RANKL-OPG, and the net balance determines bone loss in inflammatory arthritis. 1,25(OH)2D = 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D; 17-βE = 17-β estrogen; bmp = bone morphogenetic protein; GC = glucocorticoids; OB/SC = osteoblast/stromal cell; OPG = osteoprotegerin; RANKL = receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand; PTH = parathyroid hormone; TGF = transforming growth factor; TNF = tumor necrosis factor.

Once activated, the osteoclast attaches itself to the bone surface via surface integrin αvβ3 receptor and forms a 'seal' with actin [15]. Hydrochloric acid is secreted by the H+ ATPase to decalcify the bone, followed by the release of cathepsins for the degradation of bone matrix proteins. Once a certain amount of bone is resorbed, the osteoclast disengages, leaving a resorbed pit that is subsequently filled by osteoblasts [16]. In young, healthy adults, bone formation equals bone resorption, so that there is no net bone loss. However, with aging and in different disease states, bone resorption exceeds bone formation, resulting in generalized osteoporosis or localized bone loss.

Bone loss in inflammatory arthritis

RA is the prototype of inflammatory arthritis characterized by T lymphocyte activation, inflammation, and joint destruction. Adjuvant-induced arthritis (AIA) is an animal model of T lymphocyte mediated inflammatory arthritis characterized by destruction of bone and cartilage similar to that in RA. In this model, activated T cells express RANKL protein on their surface, and through binding of RANKL to RANK on preosteoclasts, these cells promote osteoclastogenesis and subsequent bone loss. Treatment of these AIA animals with OPG resulted in a decrease in osteoclast number and preservation of bone and joint structure, whereas the control animals had an increased number of osteoclasts and bone destruction [17]. T lymphocytes isolated from human joints in RA also express RANKL and may play a similar role in the bone destruction associated with this disease.

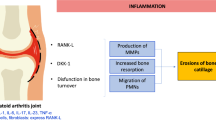

The osteoclast plays a pivotal role in RA-associated bone loss. Multinucleated cells possessing an osteoclast phenotype have been demonstrated at the bone-pannus junction and in areas of bone loss in the murine collagen-induced arthritis model [18]. Similarly, histologic sections of rheumatoid joints obtained from patients at the time of joint replacement surgery demonstrated multinucleated cells with osteoclast phenotype along the surface of resorption lacunae in subchondral bone [19]. The origin of these cells is unclear. Rheumatoid synovium is rich in macrophages. These cells share the same origin as osteoclasts and can be induced in vitro to differentiate into mature, active osteoclasts fully capable of resorbing bone [20]. It is conceivable that these multinucleated cells at the bone-pannus junction are derived from synovial macrophages in rheumatoid joints, but this has not yet been demonstrated.

Synovial fibroblasts in rheumatoid synovium may also contribute significantly to localized bone loss. These cells produce chemokines such as macrophage inflammatory peptide 1, regulated-upon-activation normal T cell expressed and secreted, IL-8, and IL-16, which promote lymphocyte infiltration and support lymphoproliferation via secretion of various colony-stimulating factors [21]. This results in a large pool of RANKL-expressing lymphocytes supporting osteoclastogenesis and local bone loss. Furthermore, synovial fibroblasts may directly contribute to local bone destruction by expressing RANKL on their surface [22,23] and by secreting cathepsins [21]. These cells have not been shown to have any bone-resorbing capacity, and any direct role of these cells in bone resorption is unknown.

Inflammatory cytokines play an important role in various inflammatory arthritides and associated bone damage. Elevated levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α have been demonstrated by immunoassays in several inflammatory arthritides [24]. TNF-α promotes expression of adhesion molecules, activation of leukocytes, recruitment of leukocytes, and production of proinflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8) in RA. It promotes osteoclastogenesis by stimulating the osteoblasts/stromal cells and possibly T lymphocytes to produce RANKL and M-CSF. In addition, recent in vitro studies have shown that TNF-α, in the presence of M-CSF, directly induces the formation of multinucleated cells containing tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase that are fully capable of resorbing bone [25,26]. This effect is independent of RANKL/RANK interaction and is potentiated by IL-1. The osteoclast progenitor cells have been shown to express both p55 and p75 TNF receptors, and TNF-α-induced osteoclast differentiation is completely blocked by anti-p55 TNF receptor antibodies [25]. In murine models, TNF-α plays a central role in periodontal osteolysis and aseptic prosthetic loosening. Bone loss in both of these processes results from TNF-α induced osteoclast activation and can be prevented by deletion of the gene for p55 TNF receptor [27,28]. In clinical studies of RA, TNF-α inhibition using soluble p75 TNF receptor (etanercept) or chimeric anti-TNF antibodies (infliximab), thus preventing TNF activation of osteoclasts and inflammatory cells, resulted in a significant decrease in the progression of joint erosions and substantial clinical improvement in synovitis [29,30].

IL-1 is a potent stimulus for bone resorption. Studies both in vitro and in vivo have shown that IL-1 can cause bone loss in RA [31,32,33,34]. IL-1 can directly support the survival, multinucleation, and activation of osteoclast-like cells [35,36,37]. IL-1 receptor mRNA has been demonstrated in murine metaphyseal and alveolar bone osteoclasts using, respectively, immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridization [38,39]. In addition, the osteoclast activation by IL-1 can be mediated via RANKL upregulation by osteoblast/stromal cells [40]. In human trials, the use of IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) in a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, controlled study of RA demonstrated a significant slowing of radiologic progression of erosions in comparison with placebo [41].

IL-6 also supports osteoclast differentiation both in vitro and in vivo [42,43,44]. Bone loss in RA and multiple myeloma is associated with high levels of circulating IL-6 [45,46]. This positive effect of IL-6 on osteoclastogenesis and bone loss appears to be independent of RANKL expression and is probably a result of a direct stimulatory effect on osteoclast precursors [40,47]. In a clinical study of patients with active RA, blocking of IL-6 using a humanized monoclonal anti-IL-6 receptor antibody caused a significant improvement in clinical symptoms and acute-phase reactants [48]. However, the overall results with anti-IL-6 therapy have been less than dramatic in comparison with the results seen with IL-1 and TNF-α blockade in clinical trials. Moreover, there are no published randomized, controlled trials that have evaluated any positive effect of anti IL-6 therapy on the progression of joint erosions and bone loss.

IL-18 mRNA and protein has been detected in significantly higher levels in rheumatoid synovium than in osteoarthritis controls [49]. IL-18 is produced by osteoblast/stromal cells and sustains Th1 response by upregulating the expression of IFN-γ, IL-2, and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) that is characteristic of RA [50]. It can act directly to induce the production of TNF-α and nitric oxide by synovial macrophages and of IL-6 and stromelysin by chondrocytes in vitro [49,51]. The coadministration of IL-18 with collagen in murine collagen-induced arthritis facilitated the development of erosive inflammatory arthritis [49]. However, IL-18 also has a potentially beneficial role, as it may inhibit osteoclasto-genesis via GM-CSF production in vitro [52]. An IL-18-binding protein has been isolated and purified and may act as an inhibitor of IL-18 signaling [53].

In summary, inflammatory cytokines contribute significantly to bone loss in RA. Their effect is mostly mediated by osteoclast activation via the RANKL/OPG pathway, although there is a strong case for a direct role of these cytokines in osteoclast formation.

Finally, while RA is associated with increased bone resorption, there is evidence that inadequate bone formation also contributes to the periarticular osteopenia and subchondral bone damage. In vitro examination of osteoblast cells removed from periarticular bone of patients with RA revealed both a higher percentage of senescent cells and a higher rate of senescence than in age-matched controls [54]. Therefore, localized bone loss in the inflammatory arthritides may result from both an enhanced bone resorption by activated osteoclasts and accompanying inadequate bone formation.

Treatment strategies

The treatment of inflammatory bone loss can be aimed at attempts to suppress bone resorption and to increase bone formation. The evidence to support the proposed treatment strategies is sparse. However, having stated this new paradigm for inflammatory bone loss, we can propose the following treatment strategies.

Suppressing cellular immune response

As discussed above regarding the AIA model of inflammatory bone loss, T lymphocytes contribute to local bone loss by promoting osteoclastogenesis via RANKL-RANK interaction in the inflamed joint and surrounding bone marrow. In addition, synovial macrophages promote joint damage in RA by secreting cytokines and supporting osteoclast function. The local infiltration of these cells and subsequent joint damage could be suppressed by blocking adhesion molecules and chemokines using mono-clonal antibodies. A placebo-controlled pilot study targeting the intercellular adhesion molecule ICAM-1, using an antisense oligodeoxynucleotide in patients with active RA, showed a modest improvement in clinical disease in the treatment group in comparison with the placebo group. [55]. More studies are needed.

It has been proposed that synovial macrophages derived from circulating monocytes are stimulated by T cell derived cytokines and other inflammatory mediators and may differentiate into osteoclasts. Therefore, depletion of synovial macrophages may be an effective intervention to prevent localized bone loss in RA. A single intra-articular administration of clodronate liposomes into the knee joints of patients with long-standing RA has successfully depleted synovial macrophages and decreased the expression of adhesion molecules ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 [56].

Suppression of T cells is a viable and promising therapeutic intervention. Previous studies aimed at depleting T cells using monoclonal antibodies were minimally successful [57]. However, current therapeutic studies targeting T cell function without reducing the number of T cells are promising. Several disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (such as cyclosporin A and leflunomide) commonly used to treat inflammatory arthritides are inhibitory to T cells and retard the development of erosions and joint damage [58,59]. New therapies focusing on inducing T cell tolerance at the level of MHC interaction appear promising.

Anticytokine therapy

As discussed above, inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, etc) promote bone loss by activating osteoclasts. TNF-α and IL-1 stimulate osteoblastic cells to express RANKL, which in turn facilitates the conversion of macrophages to osteoclasts [40,60]. In addition, these cytokines may directly stimulate osteoclast precursor cells. Inhibitors of TNF-α and IL-1 are effective in retarding joint erosions and localized bone loss in RA.

Several anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10, IL-11, IL-13, and IL-1Ra act by suppressing the production of inflammatory cytokines or by neutralizing them. Although trials with IL-10 and IL-11 have not shown any significant benefit, monoclonal antibodies against IL-1Ra and IL-6 appear promising in reducing joint inflammation and local bone damage. Given the proinflammatory role of IL-18 in RA, IL-18-binding protein is being studied as an anti-inflammatory therapy for RA. However, caution is warranted with the use of IL-18-binding protein because it may lower the production of GM-CSF and IFN-γ, thereby promoting osteoclastogenesis and exacerbating infection with intracellular pathogens, respectively.

Improving the RANKL/OPG ratio

The pivotal role of RANKL/OPG in osteoclastogenesis, osteoclast activation, and osteoclast survival has been discussed in detail. A recent preliminary study of 52 postmenopausal women treated with up to 3 mg/kg OPG infusion as a single dose resulted in a decrease in the urinary N-telopeptide/creatinine ratio by 80% within 5 days [61]. These levels remained suppressed a month after the treatment was discontinued. Moreover, combined use of OPG and parathyroid hormone in ovariectomized rats has shown an additive effect in preventing bone loss, suggesting a potential therapeutic use of intermittent OPG and parathyroid hormone to reverse both generalized and localized bone loss [62].

RANKL, also known as TNF-related, activation-induced cytokine (TRANCE), is expressed on T cells and supports the activation and survival of antigen-presenting dendritic cells that activate immune responses [17,63]. The postreceptor intracellular signaling cascade in cell cultures of dendritic cells and osteoclasts is similar with activation of NF-κB, extracellular response kinase, c-Src, phosphatidylinositide 3'-kinase, and Akt/protein kinase B that induces survival and activation of the cell [64]. In addition, RANKL induces the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1 and IL-6, and of cytokines that stimulate and induce differentiation of T cells, such as IL-12 and IL-15, by the antigen-presenting dendritic cells [65,66]. Although the (auto)antigens that lead to the chronic stimulation of T cells and/or macrophages in RA remain unknown, there is significant evidence to suggest an important role of interaction between antigen-presenting cells and T cells in this disease [67,68]. Therefore, inhibition of RANKL may have a significant effect on the immunopathogenesis of RA.

Blocking osteoclast-bone interaction

As mentioned previously, αvβ3 integrin receptor is essential for the attachment of the osteoclast to the bone. The osteoclasts obtained from αvβ3 knockout mice (β3-/-) show marked morphologic and physiologic abnormalities, including an inability to form resorption lacunae [69]. In addition, in vitro experiments using monoclonal antibody against αvβ3 (LM 609) have shown a dramatic reduction in osteoclast-mediated bone resorption [15]. Therefore, inhibition of osteoclastic bone attachment by blocking integrin receptor is a potential therapeutic alternative that needs further studying.

Inhibiting osteoclast function

Currently, the agents available to prevent and treat bone loss are referred to as 'anti-resorptives' and act by inhibiting osteoclast function. These agents, including estrogen, bisphosphonates, and calcitonin, rely on differing mechanisms to reduce the ability of osteoclasts to resorb bone. Since osteoclast-mediated bone resorption contributes to bone erosions and osteopenia, inhibition of osteoclasts with antiresorptives, i.e. bisphosphonates, may be effective in preventing bone loss in inflammatory arthritis. Clodronate, a halogen-containing bisphosphonate, can inhibit the production of IL-6, TNF-α, and nitric oxide from a macrophage cell line in vitro and has anti-inflammatory properties in RA [70,71]. Moreover, it can also inhibit col-lagenase (MMP-8) production and reduce joint destruction in established AIA in rats [72,73]. Other bisphosphonates have been shown to prevent focal bone resorption in animal models of inflammatory arthritis [74,75]. However, in clinical trials of RA, antiresorptive therapies alone have been unable to prevent focal bone loss despite a reduction in systemic bone loss [76,77,78]. In the future, larger trials using higher doses or more potent antiresorptives, earlier intervention, or a combination therapy with anabolic agents may prove effective in retarding local bone loss in inflammatory arthritis.

Activating osteoblast function

In inflammatory bone loss, there is evidence of reduced activity and possibly reduced life span of osteoblasts. Recently, animal and clinical trials utilizing daily injections of fragments of parathyroid hormone found increased osteoblast activity and life span in both postmenopausal and glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis [79,80,81]. Therefore, injections of this hormone fragment may be able to override the suppressive effects of inflammation and/or glu–cocorticoids on osteoblast function and reverse bone loss.

Conclusion

Localized bone loss in RA results from the activation of an inflammatory immune response, which increases both the number and the activity of osteoclasts. Therapy to prevent or reverse this bone loss should be directed at the suppression of inflammation, direct inhibition of osteoclast-mediated bone resorption, or stimulation of osteoblastic bone formation. All these therapeutic interventions are now or soon will be available for use in the clinic. The challenge now is to determine if altering this inflammatory induced bone loss in RA will translate into reduced functional disability. The future is promising in this scientific arena.

Abbreviations

- AIA:

-

adjuvant-induced arthritis

- GM-CSF:

-

granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor

- IFN:

-

interferon

- IL:

-

interleukin

- IL-1Ra:

-

IL-1 receptor antagonist

- M-CSF:

-

macrophage colony stimulating factor

- MHC:

-

major histocompatibility complex

- OPG:

-

osteoprotegerin

- RA:

-

rheumatoid arthritis

- RANK:

-

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB

- RANKL:

-

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand

- Th:

-

T helper

- TNF:

-

tumor necrosis factor.

References

Eggelmeijer F, Papapoulos SE, Westedt ML, Van Paassen HC, Dijkmans BA, Breedveld FC: Bone metabolism in rheumatoid arthritis; relation to disease activity. Br J Rheumatol. 1993, 32: 387-391.

Toussirot E, Ricard-Blum S, Dumoulin G, Cedoz JP, Wendling D: Relationship between urinary pyridinium cross-links, disease activity and disease subsets of ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999, 38: 21-27. 10.1093/rheumatology/38.1.21.

Mellish RW, O'Sullivan MM, Garrahan NJ, Compston JE: Iliac crest trabecular bone mass and structure in patients with non-steroid treated rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1987, 46: 830-836.

Hanson CA, Shagrin JW, Duncan H: Vertebral osteoporosis in ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Orthop. 1971, 74: 59-64.

Haugeberg G, Uhlig T, Falch JA, Halse JI, Kvien TK: Bone mineral density and frequency of osteoporosis in female patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from 394 patients in the Oslo County Rheumatoid Arthritis register. Arthritis Rheum. 2000, 43: 522-530. 10.1002/1529-0131(200003)43:3<522::AID-ANR7>3.0.CO;2-Y.

Toussirot E, Michel F, Auge B, Wendling D: Bone mass, body composition and bone ultrasound measurements in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999, 42(suppl): S356-

Formiga F, Moga I, Nolla JM, Pac M, Mitjavila F, Roig-Escofet D: Loss of bone mineral density in premenopausal women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995, 54: 274-276.

Lee SK, Goldring SR, Lorenzo JA: Expression of the calcitonin receptor in bone marrow cell cultures and in bone: a specific marker of the differentiated osteoclast that is regulated by calcitonin. Endocrinology. 1995, 136: 4572-4581.

Faust J, Lacey DL, Hunt P, Burgess TL, Scully S, Van G, Eli A, Qian Y, Shalhoub V: Osteoclast markers accumulate on cells developing from human peripheral blood mononuclear precursors. J Cell Biochem. 1999, 72: 67-80. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(19990101)72:1<67::AID-JCB8>3.0.CO;2-A.

Hattersley G, Chambers TJ: Calcitonin receptors as markers for osteoclastic differentiation: correlation between generation of bone-resorptive cells and cells that express calcitonin receptors in mouse bone marrow cultures. Endocrinology. 1989, 125: 1606-1612.

Lacey DL, Timms E, Tan HL, Kelley MJ, Dunstan CR, Burgess T, Elliott R, Colombero A, Elliott G, Scully S, Hsu H, Sullivan J, Hawkins N, Davy E, Capparelli C, Eli A, Qian YX, Kaufman S, Sarosi I, Shalhoub V, Senaldi G, Guo J, Delaney J, Boyle WJ: Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell. 1998, 93: 165-176.

Simonet WS, Lacey DL, Dunstan CR, Kelley M, Chang MS, Luthy R, Nguyen HQ, Wooden S, Bennett L, Boone T, Shimamoto G, DeRose M, Elliott R, Colombero A, Tan HL, Trail G, Sullivan J, Davy E, Bucay N, Renshaw-Gegg L, Hughes TM, Hill D, Pattison W, Campbell P, Boyle WJ: Osteoprotegerin: a novel secreted protein involved in the regulation of bone density. Cell. 1997, 89: 309-319.

The American Society for Bone and Mineral Research President's Committee on Nomenclature: : Proposed standard nomenclature for new tumor necrosis factor family members involved in the regulation of bone resorption. J Bone Miner Res. 2000, 15: 2293-2296.

Suda T, Takahashi N, Martin TJ: Modulation of osteoclast differentiation. Endocr Rev. 1992, 13: 66-80.

Ross FP, Chappel J, Alvarez JI, Sander D, Butler WT, Farach-Carson MC, Mintz KA, Robey PG, Teitelbaum SL, Cheresh DA: Interactions between the bone matrix proteins osteopontin and bone sialoprotein and the osteoclast integrin alpha v beta 3 potentiate bone resorption:. J Biol Chem. 1993, 268: 9901-9907.

Vaananen HK, Horton M: The osteoclast clear zone is a specialized cell-extracellular matrix adhesion structure. J Cell Sci. 1995, 108: 2729-2732.

Kong YY, Feige U, Sarosi I, Bolon B, Tafuri A, Morony S, Capparelli C, Li J, Elliott R, McCabe S, Wong T, Campagnuolo G, Moran E, Bogoch ER, Van G, Nguyen LT, Ohashi PS, Lacey DL, Fish E, Boyle WJ, Penninger JM: Activated T cells regulate bone loss and joint destruction in adjuvant arthritis through osteoprotegerin ligand. Nature. 1999, 402: 304-309. 10.1038/46303.

Suzuki Y, Nishikaku F, Nakatuka M, Koga Y: Osteoclast-like cells in murine collagen induced arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1998, 25: 1154-1160.

Hummel KM, Petrow PK, Franz JK, Muller-Ladner U, Aicher WK, Gay RE, Bromme D, Gay S: Cysteine proteinase cathepsin K mRNA is expressed in synovium of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and is detected at sites of synovial bone destruction. J Rheumatol. 1998, 25: 1887-1894.

Udagawa N, Takahashi N, Akatsu T, Tanaka H, Sasaki T, Nishihara T, Koga T, Martin TJ, Suda T: Origin of osteoclasts: mature monocytes and macrophages are capable of differentiating into osteoclasts under a suitable microenvironment prepared by bone marrow-derived stromal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990, 87: 7260-7264.

Kontoyiannis D, Kollias G: Fibroblast biology: synovial fibroblasts in rheumatoid arthritis: leading role or chorus line?. Arthritis Res. 2000, 2: 342-343. 10.1186/ar109.

Gravallese EM, Manning C, Tsay A, Naito A, Pan C, Amento E, Goldring SR: Synovial tissue in rheumatoid arthritis is a source of osteoclast differentiation factor. Arthritis Rheum. 2000, 43: 250-258. 10.1002/1529-0131(200002)43:2<250::AID-ANR3>3.0.CO;2-P.

Takayanagi H, Iizuka H, Juji T, Nakagawa T, Yamamoto A, Miyazaki T, Koshihara Y, Oda H, Nakamura K, Tanaka S: Involvement of receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand/osteoclast differentiation factor in osteoclastogenesis from synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000, 43: 259-269. 10.1002/1529-0131(200002)43:2<259::AID-ANR4>3.0.CO;2-W.

Illei GG, Lipsky PE: Novel, non-antigen-specific therapeutic approaches to autoimmune/inflammatory diseases. Curr Opin Immunol. 2000, 12(6): 712-718. 10.1016/S0952-7915(00)00167-9.

Azuma Y, Kaji K, Katogi R, Takeshita S, Kudo A: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces differentiation of and bone resorption by osteoclasts. J Biol Chem. 2000, 275: 4858-4864. 10.1074/jbc.275.7.4858.

Kobayashi K, Takahashi N, Jimi E, Udagawa N, Takami M, Kotake S, Nakagawa N, Kinosaki M, Yamaguchi K, Shima N, Yasuda H, Morinaga T, Higashio K, Martin TJ, Suda T: Tumor necrosis factor alpha stimulates osteoclast differentiation by a mechanism independent of the ODF/RANKL-RANK interaction. J Exp Med. 2000, 191: 275-286. 10.1084/jem.191.2.275.

Abu-Amer Y, Ross FP, Edwards J, Teitelbaum SL: Lipopolysaccharide-stimulated osteoclastogenesis is mediated by tumor necrosis factor via its P55 receptor. J Clin Invest. 1997, 100: 1557-1565.

Merkel KD, Erdmann JM, McHugh KP, Abu-Amer Y, Ross FP, Teitelbaum SL: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha mediates orthopedic implant osteolysis. Am J Pathol. 1999, 154: 203-210.

Lipsky PE, van der Heijde DM, St Clair EW, Furst DE, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR, Smolen JS, Weisman M, Emery P, Feldmann M, Harriman GR, Maini RN: Infliximab and methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2000, 343: 1594-1602. 10.1056/NEJM200011303432202.

Finck B, Fleischmann RM, Moreland LW, Schiff M, Baton J: A phase III trial of etanercept vs methotrexate (MTX) in early rheumatoid arthritis (Enbrel ERA trial). Arthritis Rheum. 1999, 42: S117-

Boyce BF, Aufdemorte TB, Garrett IR, Yates AJ, Mundy GR: Effects of interleukin-1 on bone turnover in normal mice. Endocrinology. 1989, 125: 1142-1150.

Gowen M, Wood DD, Ihrie EJ, McGuire MK, Russell RG: An interleukin 1 like factor stimulates bone resorption in vitro. Nature. 1983, 306: 378-380.

Dinarello CA: The interleukin-1 family: 10 years of discovery. FASEB J. 1994, 8: 1314-1325.

Kimble RB, Vannice JL, Bloedow DC, Thompson RC, Hopfer W, Kung VT, Brownfield C, Pacifici R: Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist decreases bone loss and bone resorption in ovariectomized rats. J Clin Invest. 1994, 93: 1959-1967.

Jimi E, Nakamura I, Duong LT, Ikebe T, Takahashi N, Rodan GA, Suda T: Interleukin 1 induces multinucleation and bone-resorbing activity of osteoclasts in the absence of osteoblasts/stromal cells. Exp Cell Res. 1999, 247: 84-93. 10.1006/excr.1998.4320.

Jimi E, Shuto T, Koga T: Macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-1 alpha maintain the survival of osteoclast-like cells. Endocrinology. 1995, 136: 808-811.

Sunyer T, Lewis J, Collin-Osdoby P, Osdoby P: Estrogen's bone-protective effects may involve differential IL-1 receptor regulation in human osteoclast-like cells. J Clin Invest. 1999, 103: 1409-1418.

Xu LX, Kukita T, Nakano Y, Yu H, Hotokebuchi T, Kuratani T, Iijima T, Koga T: Osteoclasts in normal and adjuvant arthritis bone tissues xpress the mRNA for both type I and II interleukin-1 receptors. Lab Invest. 1996, 75: 677-687.

Xu LX, Kukita T, Yu H, Nakano Y, Koga T: Expression of the mRNA for types I and II interleukin-1 receptors in dental tissues of mice during tooth development. Calcif Tissue Int. 1998, 63: 351-356. 10.1007/s002239900539.

Hofbauer LC, Lacey DL, Dunstan CR, Spelsberg TC, Riggs BL, Khosla S: Interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, but not interleukin-6, stimulate osteoprotegerin ligand gene expression in human osteoblastic cells. Bone. 1999, 25: 255-259. 10.1016/S8756-3282(99)00162-3.

Jiang Y, Genant HK, Watt I, Cobby M, Bresnihan B, Aitchison R, McCabe D: A multicenter, double-blind, dose-ranging, randomized, placebo-controlled study of recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: radiologic progression and correlation of Genant and Larsen scores. Arthritis Rheum. 2000, 43: 1001-1009. 10.1002/1529-0131(200005)43:5<1001::AID-ANR7>3.0.CO;2-P.

Kawasaki K, Gao YH, Yokose S, Kaji Y, Nakamura T, Suda T, Yoshida K, Taga T, Kishimoto T, Kataoka H, Yuasa T, Norimatsu H, Yamaguchi A: Osteoclasts are present in gp130-deficient mice. Endocrinology. 1997, 138: 4959-4965.

Ishimi Y, Miyaura C, Jin CH, Akatsu T, Abe E, Nakamura Y, Yamaguchi A, Yoshiki S, Matsuda T, Hirano T: IL-6 is produced by osteoblasts and induces bone resorption. J Immunol. 1990, 145: 3297-3303.

Manolagas SC: Role of cytokines in bone resorption. Bone. 1995, 17(2 suppl): 63S-67S. 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00180-L.

De Benedetti F, Massa M, Pignatti P, Albani S, Novick D, Martini A: Serum soluble interleukin 6 (IL-6) receptor and IL-6/soluble IL-6 receptor complex in systemic juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 1994, 93: 2114-2119.

Gaillard JP, Bataille R, Brailly H, Zuber C, Yasukawa K, Attal M, Maruo N, Taga T, Kishimoto T, Klein B: Increased and highly stable levels of functional soluble interleukin-6 receptor in sera of patients with monoclonal gammopathy. Eur J Immunol. 1993, 23: 820-824.

Vidal ON, Sjogren K, Eriksson BI, Ljunggren O, Ohlsson C: Osteoprotegerin mRNA is increased by interleukin-1 alpha in the human osteosarcoma cell line MG-63 and in human osteoblast-like cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998, 248(3): 696-700. 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9035.

Yoshizaki K, Nishimoto N, Mihara M, Kishimoto T: Therapy of rheumatoid arthritis by blocking IL-6 signal transduction with a humanized anti-IL-6 receptor antibody. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 1998, 20: 247-259. 10.1007/s002810050033.

Gracie JA, Forsey RJ, Chan WL, Gilmour A, Leung BP, Greer MR, Kennedy K, Carter R, Wei XQ, Xu D, Field M, Foulis A, Liew FY, McInnes IB: A proinflammatory role for IL-18 in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 1999, 104: 1393-1401.

Micallef MJ, Ohtsuki T, Kohno K, Tanabe F, Ushio S, Namba M, Tanimoto T, Torigoe K, Fujii M, Ikeda M, Fukuda S, Kurimoto M: Interferon-gamma-inducing factor enhances T helper 1 cytokine production by stimulated human T cells: synergism with interleukin-12 for interferon-gamma production. Eur J Immunol. 1996, 26: 1647-1651.

Olee T, Hashimoto S, Quach J, Lotz M: IL-18 is produced by articular chondrocytes and induces proinflammatory and catabolic responses. J Immunol. 1999, 162: 1096-1100.

Udagawa N, Horwood NJ, Elliott J, Mackay A, Owens J, Okamura H, Kurimoto M, Chambers TJ, Martin TJ, Gillespie MT: Interleukin-18 (interferon-gamma-inducing factor) is produced by osteoblasts and acts via granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor and not via interferon-gamma to inhibit osteoclast formation. J Exp Med. 1997, 185: 1005-1012. 10.1084/jem.185.6.1005.

Novick D, Kim SH, Fantuzzi G, Reznikov LL, Dinarello CA, Rubinstein M: Interleukin-18 binding protein: a novel modulator of the Th1 cytokine response. Immunity. 1999, 10: 127-136.

Yudoh K, Matsuno H, Osada R, Nakazawa F, Katayama R, Kimura T: Decreased cellular activity and replicative capacity of osteoblastic cells isolated from the periarticular bone of rheumatoid arthritis patients compared with osteoarthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2000, 43: 2178-2188. 10.1002/1529-0131(200010)43:10<2178::AID-ANR5>3.0.CO;2-Z.

Maksimovich W, Blackburn W, Hutchins E, William L, Tami J, Wagner K, Shanahan W: A pilot study of ISIS 2302, an anti-sense oligodeoxynucleotide, in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999, 42(suppl): S170-

Blom A, van Lent PL, van Bloois L, Beijnen JH, van Rooijen N, de Waal, Malefijt MC, van de Putte LB, Storm G, van den Berg WB: Synovial macrophage depletion with clodronate-containing liposomes in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000, 43: 1951-1959. 10.1002/1529-0131(200009)43:9<1951::AID-ANR5>3.0.CO;2-K.

Choy EH, Chikanza IC, Kingsley GH, Corrigall V, Panayi GS: Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with single dose or weekly pulses of chimaeric anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody. Scand J Immunol. 1992, 36: 291-298.

Zeidler HK, Kvien TK, Hannonen P, Wollheim FA, Forre O, Geidel H, Hafstrom I, Kaltwasser JP, Leirisalo-Repo M, Manger B, Laaso-nen L, Markert ER, Prestele H, Kurki P: Progression of joint damage in early active severe rheumatoid arthritis during 18 months of treatment: comparison of low-dose cyclosporin and parenteral gold. Br J Rheumatol. 1998, 37: 874-882. 10.1093/rheumatology/37.8.874.

Sharp JT, Strand V, Leung H, Hurley F, Loew-Friedrich I: Treatment with leflunomide slows radiographic progression of rheumatoid arthritis: results from three randomized controlled trials of leflunomide in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Leflunomide. Rheumatoid Arthritis Investigators Group. Arthritis Rheum. 2000, 43: 495-505. 10.1002/1529-0131(200003)43:3<495::AID-ANR4>3.0.CO;2-U.

Teitelbaum SL: Bone resorption by osteoclasts. Science. 2000, 289: 1504-1508. 10.1126/science.289.5484.1504.

Bekker PJ, Holloway D, Nalanishi A, Arrighi HM, Dunstan CR: Osteoprotegerin (OPG) has potent and sustained anti-resorptive activity in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 1999, 14(suppl): S180-

Kostenuik PJ, Capparelli C, Morony S, Lacey D, Dunstan C: Osteoprotegerin (OPG) and parathyroid hormone have additive effects on bone mass in aged ovariectomized rats. Osteoprosis Int. 2000, 11(suppl 2): S206-

Wong BR, Josien R, Lee SY, Sauter B, Li HL, Steinman RM, Choi Y: TRANCE (tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-related activation-induced cytokine), a new TNF family member predominantly expressed in T cells, is a dendritic cell-specific survival factor. J Exp Med. 1997, 186: 2075-2080. 10.1084/jem.186.12.2075.

Kim N, Odgren PR, Kim DK, Marks SC, Choi Y: Diverse roles of the tumor necrosis factor family member TRANCE in skeletal physiology revealed by TRANCE deficiency and partial rescue by a lymphocyte-expressed TRANCE transgene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000, 97: 10905-10910. 10.1073/pnas.200294797.

Josien R, Wong BR, Li HL, Steinman RM, Choi Y: TRANCE, a TNF family member, is differentially expressed on T cell subsets and induces cytokine production in dendritic cells. J Immunol. 1999, 162: 2562-2568.

Bachmann MF, Wong BR, Josien R, Steinman RM, Oxenius A, Choi Y: TRANCE, a tumor necrosis factor family member critical for CD40 ligand-independent T helper cell activation. J Exp Med. 1999, 189: 1025-1031. 10.1084/jem.189.7.1025.

Bresnihan B: Pathogenesis of joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1999, 26: 717-719.

Burmester GR, Stuhlmuller B, Keyszer G, Kinne RW: Mononuclear phagocytes and rheumatoid synovitis. Mastermind or workhorse in arthritis?. Arthritis Rheum. 1997, 40: 5-18.

McHugh KP, Hodivala-Dilke K, Zheng MH, Namba N, Lam J, Novack D, Feng X, Ross FP, Hynes RO, Teitelbaum SL: Mice lacking beta3 integrins are osteosclerotic because of dysfunctional osteoclasts. J Clin Invest. 2000, 105: 433-440.

Monkkonen J, Pennanen N, Lapinjoki S, Urtti A: Clodronate (dichloromethylene bisphosphonate) inhibits LPS-stimulated IL-6 and TNF production by RAW 264 cells. Life Sci. 1994, 54: PL229-234. 10.1016/0024-3205(94)00505-2.

Makkonen N, Salminen A, Rogers MJ, Frith JC, Urtti A, Azhayeva E, Monkkonen J: Contrasting effects of alendronate and clodronate on RAW 264 macrophages: the role of a bisphosphonate metabolite:. Eur J Pharm Sci. 1999, 8: 109-118. 10.1016/S0928-0987(98)00065-7.

Teronen O, Konttinen YT, Lindqvist C, Salo T, Ingman T, Lauhio A, Ding Y, Santavirta S, Sorsa T: Human neutrophil collagenase MMP-8 in peri-implant sulcus fluid and its inhibition by clodronate. J Dent Res. 1997, 76: 1529-1537.

Kinne RW, Schmidt CB, Buchner E, Hoppe R, Nurnberg E, Emmrich F: Treatment of rat arthritides with clodronate-containing liposomes. Scand J Rheumatol Suppl. 1995, 101: 91-97.

Pysklywec MW, Moran EL, Bogoch ER: Zoledronate (CGP 42'446), a bisphosphonate, protects against metaphyseal intracortical defects in experimental inflammatory arthritis. J Orthop Res. 1997, 15: 858-861.

Francis MD, Hovancik K, Boyce RW: NE-58095: a diphosphonate which prevents bone erosion and preserves joint architecture in experimental arthritis. Int J Tissue React. 1989, 11: 239-252.

Gravallese EM, Goldring SR: Cellular mechanisms and the role of cytokines in bone erosions in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000, 43: 2143-2151. 10.1002/1529-0131(200010)43:10<2143::AID-ANR1>3.3.CO;2-J.

Eggelmeijer F, Papapoulos SE, van Paassen HC, Dijkmans BA, Valkema R, Westedt ML, Landman JO, Pauwels EK, Breedveld FC: Increased bone mass with pamidronate treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Results of a three-year randomized, double-blind trial. Arthritis Rheum. 1996, 39: 396-402.

Sileghem A, Geusens P, Dequeker J: Intranasal calcitonin for the prevention of bone erosion and bone loss in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992, 51: 761-764.

Jilka RL, Weinstein RS, Bellido T, Roberson P, Parfitt AM, Manolagas SC: Increased bone formation by prevention of osteoblast apoptosis with parathyroid hormone. J Clin Invest. 1999, 104: 439-446.

Finkelstein JS, Klibanski A, Arnold AL, Toth TL, Hornstein MD, Neer RM: Prevention of estrogen deficiency-related bone loss with human parathyroid hormone (1-34): a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998, 280: 1067-1073. 10.1001/jama.280.12.1067.

Lane NE, Sanchez S, Modin GW, Genant HK, Arnaud CD: Parathyroid hormone treatment can reverse corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis. Results of a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Invest. 1998, 102: 1627-1633.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rehman, Q., Lane, N.E. Bone loss: Therapeutic approaches for preventing bone loss in inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 3, 221 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1186/ar305

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/ar305