Abstract

Introduction

At present, no disease-modifying osteoarthritis drugs (DMOADS) are approved by the FDA (US Food and Drug Administration); possibly partly due to inadequate trial design since efficacy demonstration requires disease progression in the placebo group. We investigated whether combinations of biochemical and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-based markers provided effective diagnostic and prognostic tools for identifying subjects with high risk of progression. Specifically, we investigated aggregate cartilage longevity markers combining markers of breakdown, quantity, and quality.

Methods

The study included healthy individuals and subjects with radiographic osteoarthritis. In total, 159 subjects (48% female, age 56.0 ± 15.9 years, body mass index 26.1 ± 4.2 kg/m2) were recruited. At baseline and after 21 months, biochemical (urinary collagen type II C-telopeptide fragment, CTX-II) and MRI-based markers were quantified. MRI markers included cartilage volume, thickness, area, roughness, homogeneity, and curvature in the medial tibio-femoral compartment. Joint space width was measured from radiographs and at 21 months to assess progression of joint damage.

Results

Cartilage roughness had the highest diagnostic accuracy quantified as the area under the receiver-operator characteristics curve (AUC) of 0.80 (95% confidence interval: 0.69 to 0.91) among the individual markers (higher than all others, P < 0.05) to distinguish subjects with radiographic osteoarthritis from healthy controls. Diagnostically, cartilage longevity scored AUC 0.84 (0.77 to 0.92, higher than roughness: P = 0.03). For prediction of longitudinal radiographic progression based on baseline marker values, the individual prognostic marker with highest AUC was homogeneity at 0.71 (0.56 to 0.81). Prognostically, cartilage longevity scored AUC 0.77 (0.62 to 0.90, borderline higher than homogeneity: P = 0.12). When comparing patients in the highest quartile for the longevity score to lowest quartile, the odds ratio of progression was 20.0 (95% confidence interval: 6.4 to 62.1).

Conclusions

Combination of biochemical and MRI-based biomarkers improved diagnosis and prognosis of knee osteoarthritis and may be useful to select high-risk patients for inclusion in DMOAD clinical trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a slow, chronic disease characterized by cartilage degradation and typically leading to joint space narrowing (JSN), mobility loss, pain, and eventually joint replacement.

There is presently no disease-modifying osteoarthritis drug (DMOAD) with a consistent, documented effect despite several clinical attempts in late-stage phases. Some studies may have failed due to suboptimal clinical trial design [1], resulting in very low progression in placebo patients [2–4], thus reducing the power to detect potential treatment efficacy. One phase III study demonstrated a reduction of radiographic progression in the most affected knee but no effect was observed in the contralateral knee; and without reduction of pain [5]. These findings suggest that effective therapies could be developed, but also indicate the need for tools allowing identification of rapid progressors who may be suitable for inclusion in DMOADs trials.

Total joint replacement may appear to be the most valid clinical endpoint, although it is highly dependent on local health policies, patient perception, and physician assessment. Owing to the low incidence of total joint replacement, long and large studies would be needed to detect a treatment effect using this endpoint. Alternatively, an estimate of the time to surgery could be used. At present, however, no markers have demonstrated a convincing prediction of total joint replacement [6]. Additionally, such trials would probably need to target patients with end-stage disease who may not be the most adequate subjects to be studied with chondroprotective therapies.

Structural joint damage is currently monitored by JSN from plain radiographs. Since JSN has limited sensitivity to change [2, 3, 7], large study populations are required. Secondly, radiographs do not allow direct quantitative evaluation of cartilage tissue.

DMOAD development may be improved by appropriate biomarkers during all steps of the development process [8, 9]. Several biomarker types are needed for clinical studies (Figure 1). Following the BIPED (Burden of Disease, Investigative, Prognostic, Efficacy of Intervention and Diagnostic) classification [8], a diagnostic marker would be useful to ensure inclusion of an homogenized population at a certain stage of the disease; and a prognostic marker is also needed for selecting those in this group at a high risk for disease progression. Finally, an efficacy of intervention marker is crucial for rapidly quantifying treatment response.

Marker types needed for clinical study. For a clinical study, diagnostic and prognostic markers are needed to select a population at the proper stage of osteoarthritis (OA) with a high risk of progression; and an efficacy marker is needed to evaluate the treatment effect. Supplementing the diagnostic marker, a burden of disease marker could be used to assess the total disease severity.

As an alternative to JSN for monitoring structural damage, biochemical markers of protease degraded cartilage matrix constituents have attracted research attention [9, 10]. Some markers target pathological activities such as matrix metalloproteinase-mediated collagen type II degradation or aggrecanase-mediated aggrecan degradation [11, 12]. Among them, urinary C-telopeptides of type II collagen were associated with radiographic disease risk [13, 14] and with an increase in structural damage (JSN) [13]. As an example, for short proof-of-concept phase II clinical trials, the slow progression of JSN relative to the biological variation may require large study populations – here the biochemical markers may be an appealing alternative.

Alternative imaging technologies – and particularly magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) – also seem promising to assess disease progression. Specifically, MRI offers direct assessment of cartilage [15, 16] and allows morphometric three-dimensional analysis. Several semi-automatic methods for cartilage quantification have been reported [17–19], including scoring systems integrating several joint features – for example, the Whole-Organ Magnetic Resonance Imaging Score [20]. Our group recently reported a fully automatic computer-based framework for quantification of several morphometric parameters, including cartilage volume, thickness, homogeneity, and curvature [21–24], targeting both cartilage quantity and quality.

Combinations of different marker modalities – for instance, markers of dynamic turnover (typically biochemical markers) and assessment of current status (for example, by MRI) – may provide complementary information and thereby superior identification of progressors for clinical trial design.

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate whether combinations of biochemical and imaging-based markers allowed, with higher accuracy than the individual markers, selection of the subjects at high risk of progression.

Materials and methods

The radiographs, urine samples, and MRI scans for this study were acquired at baseline (BL) and at follow-up after 21 months (FU). A subgroup had BL data re-acquired for evaluating the reproducibility of the measurements.

Population

The study included 159 subjects randomly selected to include a normal population with a large age range and a group with elevated risk of having knee OA. The majority were invited from address lists to ensure even distribution across gender and ages, supplemented with volunteers with known knee problems. The exclusion criteria ensured that no subject had previous knee joint replacement, other joint diseases (for example, rheumatoid arthritis, Paget's disease, joint fractures, hyperparathyroidism, hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism), contraindications for performing MRI examination, or were receiving medication affecting bone and/or cartilage (for example, bisphosphonates, vitamin D, hormones, selective estrogen receptor modulators, prednisolone, anabolic androgens, and parathyroid hormone). Participants were invited to attend a follow-up visit after 21 months.

From this base collection of 318 left and right knees, five knees were excluded due to inferior imaging quality. Another 25 knees were used for training of the automatic MRI quantification methods and were excluded from the evaluation set. Furthermore, a single subject was excluded since a urine sample was not acquired. Thereby, 287 knees were included in the evaluation set at BL. A subgroup of 31 knees had imaging data re-acquired 1 week after BL. At FU, 250 knees were studied.

For each test subject, their age, sex, weight, and height were recorded at BL and FU. The baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Knees were scored by the Kellgren and Lawrence index (KL) [25] for the level of OA. At BL, 51% of the evaluation knees were healthy (KL 0); the overall distribution of the KL for the 287 knees scored by the KL [25] for their level of OA was [145,87,30,24,1] (for KL 0.4). For the rescan subgroup, 35% were healthy with a KL distribution of [11,13,2,5,0]. At FU 103 of the healthy individuals had remained at KL 0, and 25 individuals had progressed (defined as an increase in KL score by one or more grades). Additionally, 10 of those individuals with OA at BL had progressed at FU after 21 months (these 10 progressors were distributed [6,3,1] from KL 1 to KL 3).

All participants signed approved information consent, and the study was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration II and European Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice [26]. The study protocol was approved by the local Ethical Committee.

Protocol and quantification for radiographs

Digital knee radiographs were acquired with the subjects standing in a weight-bearing position with knees slightly flexed and feet rotated externally. The SynaFlex (developed by Synarc, San Francisco, USA) was used to ensure position reproducibility [27].

The focus film distance was 1.0 m and tube angulation was 10° (the metatarsophalangeal view modified for fixed angle [28]). Posterior–anterior radiographs were acquired while the central beam was directed to the midpoint of the line through both popliteal regions. Radiographs of both knees were acquired simultaneously.

For each X-ray scan, the medial tibio-femoral compartment was scored by a trained radiologist. The KL was scored by qualitative evaluation of osteophytes, joint gap narrowing, and subchondral bone sclerosis for severe cases. The joint space width (JSW) was measured by manually marking the narrowest gap between the tibia and the femur. Additionally, the width of the tibial plateau was measured to quantify the knee size – covering medial and lateral compartments but excluding osteophytes. The intra-observer scan–rescan coefficients of variation were 2.5% and 0.8% for the JSW and the plateau width, respectively.

Protocol and quantification for urine samples

For all subjects, fasting morning urine samples were collected (second void). Urinary levels of collagen type II C-telopeptide fragments (CTX-II) were measured by the CartiLaps ELISA assay (Nordic Bioscience Diagnostics, Herlev, Denmark). This assay uses a monoclonal antibody mAbF46 specific for a six-amino-acid epitope (EKGPDP) derived from the collagen type II C-telopeptide [29]. CTX-II was corrected for urinary creatinine as assessed by a standard colorimetric method. To reduce measurement and to allow precision evaluation, values were calculated as the mean of two separate determinations. For the statistical analysis, the CTX-II values were logarithmically transformed to obtain normality.

Protocol and quantification for MRI

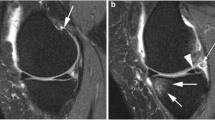

MRI scans were acquired from a 0.18 T Esaote C-span dedicated extremity scanner (Esaote, Genova, Italy). A single knee coil was used and each knee was imaged separately. We used a sagittal Turbo 3D T1 sequence with near-isotropic voxels (40° flip angle, repetition time 50 ms, echo time 16 ms, scan time 10 minutes, resolution 0.7 mm × 0.7 mm × 0.8 mm). The scans had approximately 110 slices (depending on the knee size) and each slice was 256 × 256 pixels. Near-isotropic voxels are suitable for three-dimensional image analysis in general – and are also suitable for cartilage quantification [30]. Figure 2 (top left) shows an example MRI scan. The subjects were scanned in a supine position with no load-bearing during or prior to scanning.

Magnetic resonance imaging-based biomarker quantification framework. Top left: a slice from a magnetic resonance imaging scan. Top right: segmentation of the medial tibial cartilage compartment shown in sagittal and coronal slice with a shape model fitted to the segmentation. Bottom left: thickness map. Bottom right: curvature map in the central region of interest used for the curvature marker. All computational steps are fully automatic.

The 25 scans in the training collection were segmented by slice-wise outlining of the medial tibial and femoral cartilage compartments by an expert radiologist. These segmentations were used to train a voxel classification scheme based on a multi-scale k-nearest neighbor framework [31]. This method provides automatic segmentation of the tibial and femoral cartilage compartments (Figure 2, top right).

From the segmentations, the volume and surface area were computed (MT.VC, MF.VC, MTF.VC, MT.AC, MF.AC, and MTF.AC using the Eckstein nomenclature [32]). Furthermore, the cartilage homogeneity was quantified as one minus entropy, with signal intensity entropy computed in the compartments [23] (MT.HomC, MF.HomC, MTF.HomC). Entropy quantifies the intensity histogram complexity; cartilage with more uniform intensity has lower entropy (higher homogeneity). Since the scans are T1, this measure of homogeneity is related to water distribution and proteoglycan concentration. Also, clear definition of the internal cartilage layers will be imaged by separate intensities and will contribute to higher entropy. A loss of structural integrity may therefore lead to lower entropy and higher cartilage homogeneity.

The cartilage surface roughness (inverse of smoothness) was quantified for the tibial compartment by measuring the mean surface curvature over a region-of-interest including the central load-bearing region and approximately one-half of the cartilage surface (MT.RouClAB). The surface curvature was estimated using geometric surface evolution at fine-scale resolution [21, 24, 33]. Fibrillation and minor focal lesions lead to decreased smoothness.

For the remaining quantifications, a statistical cartilage shape model was fitted to the segmented tibial cartilage sheets (Figure 2, top right). By training the model on healthy samples, the resulting cartilage model covers the bone area that a healthy cartilage sheet would cover [34]. The measured mean thickness thereby included denuded regions with zero thickness (MT.ThCtAB). The thickness map is illustrated in Figure 2 (bottom left). Additionally, the thickness map 10% quantile was used as a measure targeting local thinning related to focal lesions (denoted MT.ThCQ).

Finally, the mean surface curvature of the shape model was analyzed. Owing to model regularization this coarse scale curvature relates to the overall bending of the sheet and is therefore indirectly related to the congruity of the joint. This simplified congruity measure (MT.CongClAB) was quantified as the mean inverse curvature across the region of interest (Figure 2, bottom right) also used for the roughness measure [21, 22, 24, 33].

All steps performed on the MRI are carried out in a fully automated computer-based framework in three dimensions (rather than in each individual MRI slice). The scan – rescan precision for each marker is presented in Table 2.

Aggregate markers of cartilage longevity

We evaluated combinations of biochemical and MRI-based markers for cartilage breakdown, quantity, and quality. Such combinations may exploit complementary information from the individual markers.

From the available markers, such a combination could be CTX-II (cartilage matrix breakdown), volume (quantity), and homogeneity (quality); we denote this aggregate marker longevity-basic. Here, volume and homogeneity were totals for the tibial and femoral compartments.

A more comprehensive combination includes all the available MRI quantifications. Since some quantifications were only performed in the tibial compartment, we combined CTX-II (breakdown) with all medial tibial MRI markers: volume and thickness (quantity), area (a marker of quantity; combined with volume, it may provide an aspect of quality), congruity, roughness, and homogeneity (markers for quality). We denote this aggregate marker longevity-tib.

Finally, for comparison, we also evaluated an aggregate marker combining all medial tibial MRI markers (that is, longevity-tib without CTX-II). This was denoted MRI-tib.

We investigated the performance of linear combinations of these individual markers by means of pattern recognition methods [35]. Here, methods also exist for combining markers in non-linear or non-parametric fashion [35]. We limited ourselves to combinations defined by linear discriminant analysis, however, since it allows direct interpretation of the aggregate biomarker as a weighted sum of individual markers.

Evaluation of aggregate markers

When performing linear discriminant analysis, the resulting combination is prone to overfitting/overtraining when the number of markers is high relative to the population size, and the aggregate marker weights can be optimized to model arbitrary measurement variations that are not representative of the actual disease progression.

We therefore performed an evaluation where the population was repeatedly split randomly into two subpopulations with approximately equal size and distribution of levels of OA. For each split, we optimized the weights for the aggregate biomarker on one training subpopulation (using linear discriminant analysis) and we evaluated the resulting aggregate marker on the other evaluation subpopulation. The median performance on the evaluation subpopulations estimates the aggregate marker performance including generalization ability. We used 500 repetitions.

In order to allow direct comparison of individual and aggregate markers, we evaluated the individual markers equivalently using repeated random subpopulations.

Statistical analysis

The demographic and biochemical markers provide one measurement per subject. The markers based on radiographs and MRI scans each provide one measurement per knee. This requires specific handling of the intra-subject correlation between knee observations in the analysis. We perform this in two alternative ways in the analysis. Firstly, we combine the two knee measurements into a single subject measurement by averaging – this allows use of standard statistical analysis. Secondly, we perform analysis by generalized estimation equations (GEE) that explicitly model the inter-knee correlation within subjects.

We defined the diagnostic performance as the ability of the BL marker values to separate healthy or borderline cases (KL ≤ 1) from OA knees (KL >1). For the subject-averaged measurements this was evaluated by the P value from multivariate analysis of variation (based on Hotelling's T2 test [36]), by the corresponding required study population size calculated from power analysis (nPA) requiring 80% power and a significance level of 0.05, and by the area under the receiver-operator characteristics curve (AUC). We used DeLong and colleagues' non-parametric approach [37] to test whether AUC values were statistically different. Using GEE we also calculated the P value and the sample size (nGEE), again requiring 80% power and a significance of 0.05. The GEE P value was computed using the GEEQBOX package [38], and the sample size was calculated by a Matlab implementation of Rochon's procedure [39].

The prognostic performance was defined as the ability of the BL values to separate healthy non-progressors (KL 0 at BL and FU) from early progressors (KL 0 at BL and KL > 0 at FU), and was evaluated by the same analysis as for diagnostic markers above and then adding the odds ratio (OR). For estimating the OR, the population was split into low/high groups where the threshold for each marker was defined by cross-validation on the train/evaluation subpopulations (unless explicitly stated otherwise). The Breslow-Day test using Tarone's adjustment [40] was used for testing whether differences between ORs were statistically significant. Analysis of progression at other KL levels was not performed due to the low number of progressors.

The choices of the AUC and OR as evaluation parameters for diagnostic and prognostic markers follows the BIPED classification [8].

The potential confounding effects of gender, age, and body mass index were investigated by application of linear correction to the key aggregate markers.

Results

The diagnostic and prognostic abilities of individual and aggregate markers are presented in Table 2.

JSW performed well as a diagnostic marker (AUC = 0.73) – as expected, since it is part of the KL score. The best individual diagnostic marker was cartilage roughness (AUC = 0.80, nGEE/nPA = 31/20). The cartilage longevity marker also demonstrated good performance (AUC = 0.84, nGEE/nPA = 18/16). The AUC for longevity-tib was statistically significantly higher than for all individual markers (P < 0.05).

Several individual markers demonstrated prognostic ability, among these CTX-II (AUC = 0.67, OR = 3.2), cartilage roughness (AUC = 0.7, OR = 2.8), and cartilage homogeneity (AUC = 0.71, OR = 3.3). The JSW seemed inappropriate as a prognostic marker (P = 0.4). Cartilage longevity-tib also performed well as a prognostic marker (AUC = 0.77, OR = 5.8, nGEE/nPA = 30/32). The OR for the longevity marker was significantly higher than for all individual markers (P < 0.05) except for roughness and homogeneity (P = 0.2 and P = 0.3). The AUC was higher (P < 0.05) except for homogeneity (P = 0.12).

Cartilage longevity markers

When the individual markers are rescaled to have a standard deviation of one (denoted by underlining), the aggregate marker weights give an estimate of the marker importance. As examples, the diagnostic and prognostic cartilage longevity-tib markers (Vol: MT.VC, Area: MT.AC, Thick: MT.ThCtAB, Cong: MT.CongClAB, Rough: MT.RoughClAB, Hom: MT.HomC) were:

Below we present further results for these aggregate cartilage longevity-tib markers.

These aggregate markers are compared with the key individual markers in Figures 3 and 4. The receiver-operator characteristics curves in Figure 3 show that both the JSW and longevity were able to diagnose 57% true positives with 3.8% false positives. From there, the longevity marker proved better at diagnosing the borderline cases. The AUC for longevity was 0.87, which was superior to the AUC for a JSW of 0.73 (P = 0.02) and the AUC of 0.81 for the best individual marker roughness (P = 0.02).

Diagnostic ability for separating healthy individuals from osteoarthritis subjects. The diagnostic ability for separating healthy individuals from osteoarthritis (OA) subjects (defined by Kellgren and Lawrence index >1) of key markers, illustrated by a receiver-operator characteristics diagram. The areas under the curves are: joint space width (JSW), 0.73; urinary marker of collagen type II C-telopeptide fragment (uCTX-II), 0.70; volume, 0.52; roughness, 0.81; homogeneity, 0.65; and longevity-tib, 0.87. The aggregate longevity-tib marker provided superior ability to all the individual markers (P < 0.05).

Prognostic ability of key markers for separating healthy non-progressors from early progressors. Early progressors were defined by whether the KL score increased from a baseline score of 0. For each marker, the population was divided into quartiles and each quartile was compared with the lowest quartile in terms of the odds ratio (OR) for predicting the progressors. Each OR is given with the 95% confidence interval and with the significance level: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. Cartilage longevity-tib proved superior to the individual markers (P < 0.05) except for roughness/homogeneity (P = 0.2/0.3) with OR of 20.0 for the highest quartile. JSW = joint space width; uCTX-II, urinary marker of collagen type II C-telopeptide fragment.

Figure 4 elaborates on the prognostic performance. For each marker the scores were split into quartiles and the predictive power of elevated scores were computed by comparison with the lowest quartile. The highest quartile of the cartilage longevity marker provided an OR of 20.0 (95% confidence interval = 6.4 to 62.1).

Gender, age, and body mass index adjustment

When adjusting the longevity markers for gender, age, and body mass index, the diagnostic marker retained performance very similar to the unadjusted (AUC = 0.83, nPA = 17). The prognostic longevity marker also retained equivalent performance (AUC = 0.77, OR = 5.8, nPA = 28).

Markers normalized to knee size

In previous work, we used MRI cartilage markers normalized by the width of the tibial plateau to adjust for joint size. This improved diagnostic performance for the markers [22] and can also be used in the aggregate markers [41]. Using normalized MRI markers [22], both the diagnostic longevity marker (AUC = 0.84, nGEE/nPA = 21/16) and the prognostic longevity marker (AUC = 0.75, OR = 4.8, nGEE/nPA = 28/39) retained very similar performance as the non-normalized markers.

Diagnosis at Kellgren and Lawrence index above zero

Above, the diagnostic markers are evaluated for the ability to separate KL ≤ 1 from KL >1. In order to target diagnosis of very early OA, the separation could be KL = 0 from KL > 0. On comparing with the markers in Table 2, the best individual diagnostic markers are then the JSW (AUC = 0.70), congruity (AUC = 0.71), and homogeneity (MT.HomC, AUC = 0.70). The cartilage longevity marker allowed improved performance (AUC = 0.82, nGEE/nPA = 21/21).

Prediction of joint space narrowing and cartilage loss

The aggregate prognostic markers were optimized to predict progression in the KL score. The same prognostic longevity marker, however, also predicts increased longitudinal JSN and cartilage loss. Specifically, when dividing the knees into those above/below the mean longevity score, the mean JSN is 4.9 percentage points higher (P = 0.11), the mean tibial + femoral cartilage loss is 2.5 percentage points higher (P = 0.10), and the mean femoral cartilage loss is 2.6 percentage points higher (P = 0.05) for the high-risk group.

Discussion

The complexity of OA makes biomarker development challenging. There are many onset factors including genetics, trauma, biomechanics, weight, and exercise; and different phases of OA may entail different pathological mechanisms. Biomarkers therefore can target numerous effects, including increased turnover in cartilage and bone, fibrillation, subchondral bone thickening, bone edema, osteophytes, focal cartilage lesions, and eventually cartilage denudation (see models of OA stages [42, 43]). Owing to the heterogeneity of the disease, numerous effects will be observable concurrently in a population, and therefore aggregate markers may allow more comprehensive quantification in clinical studies.

We evaluated diagnostic and prognostics markers combining a urine-based biochemical marker for cartilage breakdown with MRI-based markers of cartilage quantity and structure. Markers combining the quantity, quality, and current breakdown could conceivably be comprehensive markers for cartilage longevity.

The major findings were twofold. The best individual diagnostic marker was cartilage roughness (AUC = 0.80, nGEE = 31) and the best individual prognostic marker was homogeneity (AUC = 0.71, nGEE = 43). Secondly, the aggregate cartilage longevity-tib marker (combining CTX-II, volume, area, thickness, congruity, roughness, and homogeneity) performed well diagnostically (AUC = 0.84, nGEE = 18) and prognostically (AUC = 0.77, OR = 5.8, nGEE = 30). The performance persisted after adjustment for gender, age, body mass index, and knee size.

Presently accepted marker

The results demonstrated that use of the JSW for population selection in clinical studies may not be optimal. The JSW was unsuitable as a prognostic marker and the diagnostic performance (AUC = 0.73) is expected since the JSW is integrated in the definition of OA (KL). Even so, roughness has a higher AUC (0.80, P < 0.05). When inspecting Figure 3, it is apparent that the JSW is effective in diagnosing the severe cases (left end of curves) corresponding to low JSW. For the earlier stages of OA, however, homogeneity and in particular cartilage longevity-tib outperforms the JSW.

Scalability for large, multicenter studies

Aggregate markers combining several individual markers introduce a potential measurement bottle-neck. Even for volumetric MRI markers, manual/semi-automatic annotation is time consuming. For advanced three-dimensional markers (such as curvature or roughness), manual annotation is not feasible.

The present study relied on fully automated computer-based MRI methods for cartilage status assessment and a standardized biochemical marker measured through standard ELISA techniques. The presented aggregate markers can thereby be applied in large, multicenter studies without introducing a reader bottle-neck.

Aggregate markers

The cartilage longevity markers support the hypothesis that markers from different modalities can be complementary. Even with similar markers, superior combined performance could be achieved by improved precision through repeated similar quantifications. The cartilage longevity-tib marker has precision 1.7/0.8%. For comparison, cartilage homogeneity has precision 0.8%. The improved performance is therefore probably due to the combination of the complementary aspects of cartilage quantity, quality, and breakdown measured from different modalities.

A potential extension of the presented methodology is to include additional complementary MRI markers targeting bone, meniscus, and other joint structures; and to include additional biochemical markers reflecting bone turnover, synovitis, cartilage formation, cartilage degradation mediated by biological processes of type II destruction different from CTX-II [44], or destruction of other matrix proteins, such as aggrecan. The aggregate markers could thereby become more similar to composite markers such as the Whole-Organ Magnetic Resonance Imaging Score [20] and the Knee Osteoarthritis Scoring System [45] MRI scoring methods. These scoring systems provide semiquantitative scores by inspection of MRI for presence/severity of disease-related parameters (for example, cartilage lesions, bone marrow abnormalities, and meniscal abnormalities). For such comprehensive aggregate markers, automatic MRI analysis will be even more important to minimize the expert reader burden.

Limitations of the study

We focused the investigation of progression of OA to the early stages. Specifically, we focused on the subpopulation with early radiographic signs of OA at baseline (KL <2). The conclusions are therefore only valid for progression during the early stages of OA. A study population with more progressed OA would be needed to validate the findings at later stages of OA. Furthermore, the relatively small number of subjects in the present study implies that the findings need to be validated on larger populations.

Furthermore, validation on larger populations is also needed to determine specific threshold values for the different markers – for example, for determining the high-risk population. In addition, the somewhat complicated nature of aggregate markers implies that validation on several populations is needed to facilitate the clinical interpretation and confidence in the markers.

The cartilage measurements were based on an MRI scanner with a 0.18 T magnet. The use of low-field MRI is sparsely validated compared with high-field MRI [46]. In particular, high-field MRI may allow cartilage volume measurements with higher accuracy and precision (implying that studies may be conducted with smaller populations). Low-field MRI, however, is much cheaper and easier to install and maintain. Future studies are needed to evaluate whether low-field MRI can be a cost-effective alternative to high-field MRI for clinical studies.

The study used the common KL score as the definition of OA. This score is not compartment specific or feature specific, whereas the markers were both compartment specific (MRI), joint specific (JSW), and not joint specific (CTX-II). Future studies are needed to elucidate the relationships between specific features and specific compartments – for example, studies similar to that of Blumenkrantz and colleagues [47].

Conclusions

Owing to the complexity of OA, it is unlikely that any single marker will be suitable for all stages of the disease. The different biomarker modalities, however, may offer complementary information, which suggests that aggregate markers may provide superior biomarker performance.

In the present study we evaluated markers from urine samples, radiographs, and MRI scans. The results demonstrated that aggregate markers may indeed provide superior diagnostic and prognostic markers; the proposed cartilage longevity marker combining aspects of cartilage quantity, quality, and breakdown performed well both as a diagnostic and a prognostic marker.

The proposed aggregate marker methodology may therefore have a direct impact on clinical study design. By allowing selection of a high-risk population, the study sample size can be lowered while still improving the chance of a positive study outcome. This should facilitate the development of effective DMOADs.

Abbreviations

- AC:

-

cartilage area

- AUC:

-

area under the receiver-operator characteristics curve

- BIPED:

-

Burden of Disease, Investigative, Prognostic, Efficacy of Intervention and Diagnostic

- BL:

-

baseline

- CongClAB:

-

cartilage congruity over the load-bearing area of bone

- CTX-II:

-

marker of collagen type II C-telopeptide fragment

- DMOAD:

-

disease-modifying osteoarthritis drug

- ELISA:

-

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FDA:

-

US Food and Drug Administration

- FU:

-

follow-up

- GEE:

-

generalized estimation equations

- HomC:

-

cartilage homogeneity

- JSN:

-

joint space narrowing

- JSW:

-

joint space width

- KL:

-

Kellgren and Lawrence index

- MF:

-

medial femoral

- MRI:

-

magnetic resonance imaging

- MT:

-

medial tibial

- MTF:

-

medial tibio-femoral

- n GEE :

-

required study population size calculated from GEE

- n PA :

-

required study population size calculated from power analysis

- OA:

-

osteoarthritis

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- RouClAB:

-

cartilage roughness over the load-bearing area of bone

- ThCtAB:

-

cartilage thickness over the total area of bone

- ThCQ:

-

cartilage thickness 10% quantile

- VC:

-

cartilage volume.

References

Abramson SB, Attur M, Yazici Y: Prospects for disease modification in osteoarthritis. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2006, 2: 304-312. 10.1038/ncprheum0193.

Bingham CO, Buckland-Wright JC, Garnero P, Cohen SB, Dougados M, Adami S, Clauw DJ, Spector TD, Pelletier JP, Raynauld JP, Strand V, Simon LS, Meyer JM, Cline GA, Beary JF: Risedronate decreases biochemical markers of cartilage degradation but does not decrease symptoms or slow radiographic progression in patients with medial compartment osteoarthritis of the knee: results of the two-year multinational knee osteoarthritis structural arthritis study. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54: 3494-3507. 10.1002/art.22160.

Spector TD, Conaghan PG, Buckland-Wright JC, Garnero P, Cline GA, Beary JF, Valent DJ, Meyer JM: Effect of risedronate on joint structure and symptoms of knee osteoarthritis: results of the BRISK randomized, controlled trial [ISRCTN01928173]. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005, 7: R625-R633. 10.1186/ar1716.

Krzeski P, Buckland-Wright C, Bálint G, Cline GA, Stoner K, Lyon R, Beary J, Aronstein WS, Spector TD: Development of musculoskeletal toxicity without clear benefit after administration of PG-116800, a matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor, to patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized, 12-month, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007, 9: R109-10.1186/ar2315.

Brandt KD, Mazzuca SA, Katz BP, Lane KA, Buckwalter KA, Yocum DE, Wolfe F, Schnitzer TJ, Moreland LW, Manzi S: Effects of doxycycline on progression of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52: 2015-2025. 10.1002/art.21122.

Altman RD, Abadie E, Avouac B, Bouvenot G, Branco J, Bruyere O, Calvo G, Devogelaer JP, Dreiser RL, Herrero-Beaumont G, Kahan A, Kreutz G, Laslop A, Lemmel EM, Menkes CJ, Pavelka K, van de PL, Vanhaelst L, Reginster JY: Total joint replacement of hip or knee as an outcome measure for structure modifying trials in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005, 13: 13-19. 10.1016/j.joca.2004.10.012.

Hunter DJ, Zhang YQ, Tu X, LaValley M, Niu JB, Amin S, Guermazi A, Genant H, Gale D, Felson DT: Change in joint space width. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54: 2488-2495. 10.1002/art.22016.

Bauer DC, Hunter DJ, Abramson SB, Attur M, Corr M, Felson D, Heinegard D, Jordan JM, Kepler TB, Lane NE, Saxne T, Tyree B, Kraus VB: Classification of osteoarthritis biomarkers: a proposed approach. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006, 14: 723-727. 10.1016/j.joca.2006.04.001.

Schaller S, Henriksen K, Hoegh-Andersen P, Sondergaard BC, Sumer EU, Tanko LB, Qvist P, Karsdal MA: In vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo methodological approaches for studying therapeutic targets of osteoporosis and degenerative joint diseases: how biomarkers can assist?. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2005, 3: 553-580. 10.1089/adt.2005.3.553.

Abadie E, Ethgen D, Avouac B, Bouvenot G, Branco J, Bruyere O, Calvo G, Devogelaer JP, Dreiser RL, Herrero-Beaumont G, Kahan A, Kreutz G, Laslop A, Lemmel EM, Nuki G, Putte LVD, Vanhaels L, Reginster JY: Recommendations for the use of new methods to assess the efficacy of disease-modifying drugs in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004, 12: 263-268. 10.1016/j.joca.2004.01.006.

Karsdal MA, Sumer EU, Wulf H, Madsen SH, Christiansen C, Fosang AJ, Sondergaard BC: Induction of increased cAMP levels in articular chondrocytes blocks matrix metalloproteinase-mediated cartilage degradation, but not aggrecanase-mediated cartilage degradation. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56: 1549-1558. 10.1002/art.22599.

Sondergaard BC, Henriksen K, Wulf H, Oestergaard S, Schurigt U, Brauer R, Danielsen I, Christiansen C, Qvist P, Karsdal MA: Relative contribution of matrix metalloprotease and cysteine protease activities to cytokine-stimulated articular cartilage degradation. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006, 14: 738-748. 10.1016/j.joca.2006.01.016.

Reijman M, Hazes JMW, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Koes BW, Christgau S, Christiansen C, Uitterlinden AG, Pols HAP: A new marker for osteoarthritis: cross-sectional and longitudinal approach. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 50: 2471-2478. 10.1002/art.20332.

Meulenbelt I, Kloppenburg M, Kroon HM, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, Garnero P, Hellio-Le Graverand MP, DeGroot J, Slagboom PE: Clusters of biochemical markers are associated with radiographic subtypes of osteoarthritis (OA) in subject with familial OA at multiple sites. The GARP study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007, 15: 379-385. 10.1016/j.joca.2006.09.007.

Drape JL, Pessis E, Auleley GR, Chevrot A, Ayral MDX: Quantitative MR imaging evaluation of chondropathy in osteoarthritic knees. Radiology. 1998, 208: 49-55.

Pessis E, Drape JL, Ravaud P, Chevrot A, Ayral MDX: Assessment of progression in knee osteoarthritis: results of a 1 year study comparing arthroscopy and MRI. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2003, 11: 361-369. 10.1016/S1063-4584(03)00049-9.

Stammberger T, Eckstein F, Englmeier KH, Reiser M: Determination of 3D cartilage thickness data from MR imaging: computational method and reproducibility in the living. Magn Reson Med. 1999, 41: 529-536. 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2594(199903)41:3<529::AID-MRM15>3.0.CO;2-Z.

Grau V, Mewes AUJ, Alcaniz M, Kikinis R, Warfield SK: Improved watershed transform for medical image segmentation using prior information. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2004, 23: 447-458. 10.1109/TMI.2004.824224.

Pakin SK, Tamez-Pena JG, Totterman S, Parker KJ: Segmentation, surface extraction and thickness computation of articular cartilage. SPIE Medical Imaging. 2002, 4684: 155-166.

Peterfy CG, Guermazi A, Zaim S, Tirman PFJ, Miaux Y, White D, Kothari M, Lu Y, Fye K, Zhao S, Genant HK: Whole-Organ Magnetic Resonance Imaging Score (WORMS) of the knee in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004, 12: 177-190. 10.1016/j.joca.2003.11.003.

Folkesson J, Dam EB, Olsen OF, Karsdal MA, Pettersen PC, Christiansen C: Automatic quantification of local and global articular cartilage surface curvature: biomarkers for osteoarthritis?. Magn Reson Med. 2008, 59: 1340-1346. 10.1002/mrm.21560.

Dam EB, Folkesson J, Pettersen PC, Christiansen C: Automatic morphometric cartilage quantification in the medial tibial plateau from MRI for osteoarthritis grading. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007, 15: 808-818. 10.1016/j.joca.2007.01.013.

Qazi AA, Folkesson J, Pettersen PC, Karsdal MA, Christiansen C, Dam EB: Separation of healthy and early osteoarthritis by automatic quantification of cartilage homogeneity. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007, 15: 1199-1206. 10.1016/j.joca.2007.03.016.

Folkesson J, Dam EB, Olsen OF, Christiansen C: Accuracy evaluation of automatic quantification of the articular cartilage surface curvature from MRI. Acad Radiol. 2007, 14: 1221-1228. 10.1016/j.acra.2007.07.001.

Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS: Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957, 16: 494-501. 10.1136/ard.16.4.494.

Verheugen G: Commission directive 2005/28/ec laying down principles and guidelines for good clinical practice as regards investigational medicinal products for human use, as well as the requirements for authorization of the manufacturing or importation of such products. Official Journal of the European Union. 2005, Legislation 091: 13-19.

Peterfy C, Li J, Zaim S, Duryea J, Lynch JA, Miaux Y, yu W, Genant HK: Comparison of fixed-flexion positioning with fluoroscopic semi-flexed positioning for quantifying radiographic joint-space width in the knee: test – retest reproducibility. Skeletal Radiol. 2003, 32: 128-132.

Duddy J, Kirwan JR, Szebenyi B, Clarke S, Granell R, Volkov S: A comparison of the semiflexed (MTP) view with the standing extended view (SEV) in the radiographic assessment of knee osteoarthritis in a busy routine X-ray department. Rheumathology (Oxford). 2005, 44: 349-351. 10.1093/rheumatology/keh476.

Christgau S, Garnero P, Fledelius C, Moniz C, Ensig M, Gineyts E, Rosenquist C, Qvist P: Collagen type II C-telopeptide fragments as an index of cartilage degradation. Bone. 2001, 29: 209-215. 10.1016/S8756-3282(01)00504-X.

Xia Y: The total volume and the complete thickness of articular cartilage determined by MRI. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2003, 11: 473-474. 10.1016/S1063-4584(03)00076-1.

Folkesson J, Dam EB, Olsen OF, Pettersen PC, Christiansen C: Segmenting articular cartilage automatically using a voxel classification approach. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2007, 26: 106-115. 10.1109/TMI.2006.886808.

Eckstein F, Ateshian G, Burgkart R, Burstein D, Cicuttini F, Dardzinski B, Gray M, Link TM, Majumdar S, Mosher T, Peterfy C, Totterman S, Waterton J, Winalski CS, Felson D: Proposal for a nomenclature for MRI based measures of articular cartilage in OA. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006, 14: 974-983. 10.1016/j.joca.2006.03.005.

Folkesson J, Dam EB, Olsen OF, Pettersen PC, Christiansen C: Automatic curvature analysis of the articular cartilage surface. Proceedings of MICCAI Joint Disease: 2006; Copenhagen. 2006, 17-24.

Dam EB, Folkesson J, Pettersen PC, Christiansen C: Automatic cartilage thickness quantification using a statistical shape model. Proceedings of MICCAI Joint Disease: 2006; Copenhagen. 2006, 42-49.

Duda RO, Hart PE, Stork DG: Pattern Classification. 2001, Wiley, New York

Hotelling H: A Generalized T test and measures of multivariate dispersion. Proceedings of the Second Berkeley Symposium: 1951; Berkeley, CA. 1951, 23-42.

DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL: Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988, 44: 837-845. 10.2307/2531595.

Ratcliffe SJ, Shults J: GEEQBOX: a MATLAB toolbox for generalized estimating equations and quasi-least squares. J Stat Software. 2008, 25: 1-14.

Rochon J: Application of GEE procedures for sample size calculations in repeated measures experiments. Stat Med. 1998, 17: 1643-1658. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19980730)17:14<1643::AID-SIM869>3.0.CO;2-3.

Tarone RE: On heterogeneity tests based on efficient scores. Biometrika. 1985, 72: 91-95. 10.1093/biomet/72.1.91.

Dam EB, Loog M, Christiansen C, Karsdal MA: Cartilage longevity: a prognostic OA biomarker combining biochemical and MRI-based cartilage markers [abstract]. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007, 15: C48-10.1016/S1063-4584(07)61700-2.

Altman RD, Gold GE: Atlas of individual radiographic features in osteoarthritis, revised. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007, 15 (Suppl A): A1-A56. 10.1016/j.joca.2006.11.009.

Qvist P, Bay-Jensen AC, Christiansen C, Dam EB, Pastoureau P, Karsdal MA: The disease modifying osteoarthritis drug (DMOAD): is it in the horizon?. Pharmacol Res. 2008, 58: 1-7. 10.1016/j.phrs.2008.06.001.

Garnero P, Charni N, Juillet F, Conrozier T, Vignon E: Increased urinary type II collagen helical and C telopeptide levels are independently associated with a rapidly destructive hip osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006, 65: 1639-1644. 10.1136/ard.2006.052621.

Kornaat PR, Ceulemans RY, Kroon HM, Riyazi N, Kloppenburg M, Carter WO, Woodworth TG, Bloem JL: MRI assessment of knee osteoarthritis: Knee Osteoarthritis Scoring System (KOSS) – inter-observer and intra-observer reproducibility of a compartment-based scoring system. Skeletal Radiol. 2005, 34: 95-102. 10.1007/s00256-004-0828-0.

Eckstein F, Cicuttini F, Raynauld JP, Waterton JC, Peterfy C: Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of articular cartilage in knee osteoarthritis (OA): morphological assessment. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006, 14 Suppl A: A46-A75. 10.1016/j.joca.2006.02.026.

Blumenkrantz G, Lindsey CT, Dunn TC, Jin H, Ries MD, Link TM, Steinbach LS, Majumdar S: A pilot, two-year longitudinal study of the interrelationship between trabecular bone and articular cartilage in the osteoarthritic knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004, 12: 997-1005. 10.1016/j.joca.2004.09.001.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding from the Danish Research Foundation (Den Danske Forskningsfond) supporting this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

EBD and IB are employees of Nordic Bioscience. MN is partly funded by Nordic Bioscience. CC and MAK are employees and shareholders of Nordic Bioscience. PCP is employed by the Center for Clinical and Basic Research (CCBR). JF and AAQ have both received scholarships partly funded by Nordic Bioscience. ML was previously partly funded by Nordic Bioscience. PG is employed by CCBR-Synarc. The study was sponsored by CCBR and Nordic Bioscience. The commercial rights to the software used for automatic cartilage quantification from MRI are held by Nordic Bioscience. A patent for the proposed Longevity markers is pending.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed to the discussion leading to the study and the writing of the manuscript. In particular, the marker combination methodology was developed by EBD and ML. The statistical analysis was designed and carried out by EBD and IB. The MRI analysis methods were developed by JF, AAQ, MN, and EBD. The radiological reading was performed by PCP. The biochemical marker expertise and measurements were provided by IB, CC, MAK, and PG. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Dam, E.B., Loog, M., Christiansen, C. et al. Identification of progressors in osteoarthritis by combining biochemical and MRI-based markers. Arthritis Res Ther 11, R115 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2774

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2774