Abstract

Introduction

Both genetic and environmental factors contribute to rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a common and complex autoimmune disease. As well as the major susceptibility gene HLA-DRB1, recent genome-wide and candidate-gene studies reported additional evidence for association of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers in the PTPN22, STAT4, OLIG3/TNFAIP3 and TRAF1/C5 loci with RA. This study was initiated to investigate the association between defined genetic markers and RA in a Slovak population. In contrast to recent studies, we included intensively-characterized osteoarthritis (OA) patients as controls.

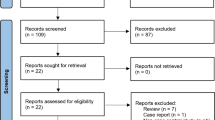

Methods

We used material of 520 RA and 303 OA samples in a case-control setting. Six SNPs were genotyped using TaqMan assays. HLA-DRB1 alleles were determined by employing site-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification.

Results

No statistically significant association of TRAF1/C5 SNPs rs3761847 and rs10818488 with RA was detected. However, we were able to replicate the association signals between RA and HLA-DRB1 alleles, STAT4 (rs7574865), PTPN22 (rs2476601) and OLIG3/TNFAIP3 (rs10499194 and rs6920220). The strongest signal was detected for HLA-DRB1*04 with an allelic P = 1.2*10-13 (OR = 2.92, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 2.18 – 3.91). Additionally, SNPs rs7574865 STAT4 (P = 9.2*10-6; OR = 1.71, 95% CI = 1.35 – 2.18) and rs2476601 PTPN22 (P = 9.5*10-4; OR = 1.67, 95% CI = 1.23 – 2.26) were associated with susceptibility to RA, whereas after permutation testing OLIG3/TNFAIP3 SNPs rs10499194 and rs6920220 missed our criteria for significance (Pcorr = 0.114 and Pcorr = 0.180, respectively).

Conclusions

In our Slovak population, HLA-DRB1 alleles as well as SNPs in STAT4 and PTPN22 genes showed a strong association with RA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is influenced by both environmental and genetic determinants with a concordance rate in monozygotic twins between 12% and 30% and a λ s ranging from three to seven [1]. One of the first known genetic loci responsible for susceptibility to RA was found within the major histocompatibility complex, namely immune response genes in the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II region [2].

Recent genome-wide association studies have confirmed known and identified new genetic determinants of RA [3]. The well studied associations with HLA-DRB1 and PTPN22 explain about 50% of the genetic contribution to RA disease susceptibility [4]. For other polymorphisms, strong associations with RA were demonstrated, namely for a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the STAT4 gene, for two independent alleles at chromosome 6q23 near OLIG3 and TNFAIP3 genes, and for SNPs near TRAF1 and C5 genes [5–9].

In contrast to recent studies, we performed a replication study of seven genetic polymorphisms in Slovak patients with chronic RA as cases and with chronic osteoarthritis (OA) as controls. RA and OA share some features of pathology, but in detail seem to be quite different entities [10–13]. For a functional variant in the GDF5 gene, it was recently shown that risk of both RA and OA is increased [14, 15]. Therefore, more genetic markers might be involved in both diseases.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study aimed at examining a genetic association in a RA-OA case-control setting in a Slovak population.

Materials and methods

Study participants

A total of 520 Slovak individuals (87 males, 433 females) with the diagnosis of RA were recruited to this study. All RA cases fulfilled the diagnostic features based on the established American College of Rheumatology criteria [13]. Controls (60 males, 243 females) were unrelated individuals from Slovakia who did not have any indication of RA but were affected by OA and intensively characterized. Further phenotypic details are shown in Table 1. Our study population did not differ in gender between RA cases and RA-free OA controls. Controls with OA are significantly older but free of RA symptoms and are rheumatoid factor (RF) negative. Both serum anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) and C-reactive protein levels are significantly lower in OA than in RA cases (Table 1).

Measurement of antibody against CCP was carried out using an anti-CCP-ELISA (Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions. From a total of 428 individuals (304 RA patients, 124 OA patients) anti-CCP antibodies were determined. Values less than 4.2 RU/ml were considered as anti-CCP negative. No value exceeded the proposed linear range of up to 196 RU/ml. The RF was determined by standard techniques in the Laboratories of the National Institute of Rheumatic Diseases, Piestany, Slovakia.

Written consent was obtained from the patients according to the current Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the National Institute of Rheumatic Diseases, Piestany, Slovakia.

Marker selection and genetic analyses

SNPs in or near the genes PTPN22, STAT4, OLIG3/TNFAIP3, and TRAF1/C5 were selected from recent genome-wide association studies with replication studies and candidate-gene approaches (Table 2) [4–9].

Genomic DNA was isolated from whole blood samples using the PureGene DNA Blood Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). DNA samples were genotyped using 5' exonuclease TaqMan® technology (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), as recently described [16]. In brief, for each genotyping experiment 10 ng DNA was used in a total volume of 5 μl containing 1 × TaqMan® Genotyping Master Mix (Applied Biosystems Foster City, CA, USA). PCR and post-PCR endpoint plate read was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions using the Applied Biosystems 7900 HT Real-Time PCR System (Foster City, CA, USA). Sequence Detection System software version 2.3 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) was used to assign genotypes applying the allelic discrimination test. Case and control DNA was genotyped together on the same plates with duplicates of samples (15%) to assess intraplate and interplate genotype quality. No genotyping discrepancies were detected. Assignment of genotypes was performed by a person with no knowledge of the proband's affection status.

HLA-DRB1 genotyping was carried out using PCR with HLA-DRB1 low-resolution exon 2 sequence-specific primers as previously described [17]. Absence or presence of HLA-DRB1 specific products was visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis, photographed, and documented.

HLA-DRB1 alleles were classified according to the nomenclature proposed by the World Health Organization Nomenclature Committee for factors of the HLA system [18]. For shared epitope (SE) association with RA, the classification system from de Vries was employed [19]. Due to frequencies below 1% for protective HLA-DRB1 allele *0402 and neutral alleles *0403, *0406, and *0407, we did not analyse the *04 group in high resolution and considered *04 in total as SE [20]. With only three alleles in our study population (one in OA controls and two in RA cases), HLA-DRB1*0103 was not used as a separate genotype and therefore *01 was also considered as SE in total.

Statistical analyses

To determine whether the genotypes of cases and controls of all SNPs deviated from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, actual and predicted genotype counts of both groups were compared by an exact test [21]. Differences between dichotomous traits were calculated employing a chi-squared test. Genotypes were coded for both dominant and recessive effects (genotype 22 + 12 versus 11 and genotype 22 versus 11 + 12, respectively, with the minor allele coded as 2). The additive genetic model was calculated using Armitage's trend test [22]. To test for epistatic interaction between SNP markers a logistic regression model based on allele dosage for each SNP was carried out. Differences in continuous variables between groups were calculated using a two-tailed t-test for normally distributed values or using the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test for variables failing normal distribution as determined by the Shapiro-Wilk test. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to examine the association between SNPs and RA with HLA-DRB1 genotypes as covariates. Prevalence odds ratios (OR) with their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported. Correction for multiple testing was carried out using the Bonferroni adjustment. For post-hoc power calculation Fisher's exact test was used. A one-sided P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Association analyses were performed using JMP 7.0.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA) and PLINK v1.04 [23, 24]. For analysis of linkage disequilibrium (LD) and for permutation testing HaploView v4.1 was employed [25, 26]. Power analysis was carried out using G*Power 3.0.10 [27, 28].

Results

Genetic analyses – SNP marker association

We analyzed six SNPs with prior evidence of association with RA in genome-wide association studies and candidate-gene approaches, namely in or near the genes PTPN22, STAT4, OLIG3/TNFAIP3, and TRAF1/C5 (Tables 2 and 3) [4–9]. Additionally, HLA-DRB1 alleles were determined in low resolution and classified in respect to the SE [see Table S1 in Additional data file 1].

For all six SNP markers analyzed, call rates were greater than 98.5% and no deviation from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was observed both in RA cases and RA-free OA controls (Table 4). Between TRAF1 and C5 SNPs on chromosome 9 (rs3761847 and rs10818488, respectively) strong LD exist with an r2 value of 0.99. Weak LD (r2= 0.08) was detected between the two SNPs on chromosome 6 (rs10499194 and rs6920220), whereas the other SNPs are unlinked (r2 = 0) and lie on different chromosomes.

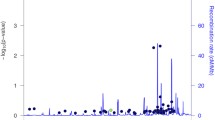

A strong association between two SNPs (rs7574865 STAT4 and rs2476601 PTPN22 ) and RA was detected, whereas for OLIG3/TNFAIP3 SNPs rs10499194 and rs6920220 nominal association was found. TRAF1/C5 SNPs rs3761847 and rs10818488 did not reach statistical significance in our study population (Table 5). However, OR for all SNPs are shifted in the same direction as previously published (Table 3). After correction for multiple testing (six SNPs), allelic P-values were still significant for rs7574865 STAT4 and rs2476601 PTPN22 (Pcorr = 5.5 × 10-5 and Pcorr = 5.7 × 10-3, respectively), but not for the other four SNPs (Table 5). Different genetic models revealed no considerable stronger association than observed by comparison of allele frequencies [see Table S2 in Additional data file 1]. After 100,000 permutation testings, rs7574865 STAT4 still showed the strongest association signal (P = 8.0 × 10-5) with rs2476601 PTPN22 (P = 5.9 × 10-3). The other SNPs failed to reach a level of statistical significance (rs6920220 OLIG3/TNFAIP3 , P = 0.105; rs10499194 OLIG3/TNFAIP3 , P = 0.152; rs3761847 TRAF1/C5 , P = 0.966; rs10818488 TRAF1/C5 , P = 0.996).

Analysis of epistasis revealed no significant interaction between the six SNPs (best P = 0.063 for epistatic interaction between rs7574865 STAT4 and rs2476601 PTPN22 , and between rs7574865 STAT4 and rs10499194 OLIG3/TNFAIP3 with P = 0.073). In particular, the two SNPs localized on chromosome 6 between OLIG3 and TNFAIP3 genes (rs10499194 and rs6920220) showed no interaction (P = 0.425).

Gender-specific analyses showed no association between the six SNPs and RA in the male subgroup (87 cases, 60 controls) [see Table S3 in Additional data file 1]. However, in the female subgroup (433 cases, 243 controls) the SNPs rs7574865 STAT4 , rs2476601 PTPN22 , and rs10499194 OLIG3/TNFAIP3 were associated with susceptibility to RA [see Table S4 in Additional data file 1], even after correction for multiple testing (Pcorr = 2.8 × 10-5, Pcorr = 9.0 × 10-3 and Pcorr = 0.037, respectively).

In a subset analysis of RA samples stratified to RF status, no association between SNPs and RF status were found by comparison of RF-positive and RF-negative RA cases [see Table S5 in Additional data file 1]. In contrast, RF-positive and RF-negative RA cases compared with OA controls showed effects for SNPs rs7574865 STAT4 and rs2476601 PTPN22 in the same order of magnitude (OR = 1.62 to 1.74) as the whole RA sample [see Tables S6 and S7 in Additional data file 1].

To test for an influence of serum anti-CCP antibody on RA susceptibility, association analyses between SNPs and RA were carried out in stratified subgroups [see Tables S8 to S10 in Additional data file 1]. Only PTPN22 SNP rs2476601 reached statistical significance after correction for multiple testing when comparing anti-CCP-positive RA patients with OA controls (Pcorr = 2.5 × 10-3).

Genetic analyses – HLA allele association

HLA-DRB1 alleles were determined in 795 individuals (96.6%). Borderline deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was found for HLA-DRB1*01 in controls and for *07 in cases (Table 6).

Except for HLA-DRB1*01, all association results confirmed our assumption of HLA-DRB1 allele classification [see Table S1 in Additional data file 1] (Table 7). Highest signals for risk association to RA were observed for HLA-DRB1*04 and *10 (Table 7). HLA-DRB1*07, *12, *13, and *15 showed protective effects (Table 7). After correction for multiple testing (13 tests), alleles *04, *07, and *13 still remained significant (Pcorr = 2.0 × 10-12, Pcorr = 0.010 and Pcorr = 2.3 × 10-4, respectively).

In gender-specific analyses, we found associations to RA susceptibility in our male subgroup for HLA-DRB1*04 and protective effects for alleles *12 and *13 [see Table S11 in Additional data file 1]. However, after correction for multiple testing, only allele *13 achieved marginal statistical significance (Pcorr = 0.043). The female subgroup showed almost the same pattern of association as the whole population, except for alleles *11 and *12 [see Table S12 in Additional data file 1], whereas after correction for multiple testing, alleles *04, *07, and *13 still met our criteria for significance (Pcorr = 6.9 × 10-11, Pcorr = 2.1 × 10-3, and Pcorr = 0.014, respectively). In both genders, no inflation of association signals was caused by deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium [see Tables S11 and S12 in Additional data file 1].

Additionally, we carried out a subset analysis of RA samples stratified to RF status. Association between RA and HLA-DRB1 alleles *04, *07, and *11 was detected by comparison of RF-positive and RF-negative RA cases [see Table S13 in Additional data file 1], whereas after correction for multiple testing, alleles *04 and *07 still met our criteria for significance (Pcorr = 0.018 for both alleles). Comparison of RF-positive cases with OA controls showed association signals for HLA-DRB1 alleles *04, *07, *10, *11, *12, and *13, after correction for multiple testing alleles *11 and *12 failed significance [see Table S14 in Additional data file 1]. Alleles *04, *13, and *15 were associated with RA when comparing RF-negative cases with OA controls [see Table S15 in Additional data file 1], but only risk allele *04 met significance criteria after correction for multiple testing (Pcorr = 5.3 × 10-5).

Stratification for serum anti-CCP antibody showed risk effect of HLA-DRB1*04 and protective effect of allele *13 in RA patients [see Table S16 in Additional data file 1] even after correction for multiple testing (Pcorr = 0.025 and Pcorr = 0.036, respectively). Comparison of anti-CCP-positive RA cases with anti-CCP-negative OA controls revealed several association signals, whereas anti-CCP-negative RA cases did not [see Tables S17 and S18 in Additional data file 1].

Assuming a dominant genetic model for HLA-DRB1 alleles, we carried out a multiple logistic regression analysis to test for interactions between HLA-DRB1 alleles and the six SNPs. Taking into account all 13 HLA-DRB1 alleles, a significant association between RA and rs7574865 STAT4 as well as rs2476601 PTPN22 remained (P = 2.8 × 10-4 and P = 1.9 × 10-3, respectively), whereas the other SNPs failed to reach the level of statistical significance (rs10499194 OLIG3/TNFAIP3 , P = 0.140; rs6920220 OLIG3/TNFAIP3 , P = 0.079; rs3761847 TRAF1/C5 , P = 0.771; rs10818488 TRAF1/C5 , P = 0.897). After adjustment for only risk HLA-DRB1 alleles *04 and *10, for four SNPs signficant association was detected (rs7574865 STAT4 , P = 1.4 × 10-5; rs2476601 PTPN22 , P = 1.2 × 10-3; rs6920220 OLIG3/TNFAIP3 , P = 4.6 × 10-3; rs10499194 OLIG3/TNFAIP3 , P = 0.017) but not for rs3761847 TRAF1/C5 and rs10818488 TRAF1/C5 (P = 0.790 and P = 0.943, respectively).

Discussion

This study investigated the relation between known susceptibility alleles and RA in a Slovak population. In contrast to recent studies, we compared RA cases with gender-matched OA controls. Therefore, this paper is the first to analyze the differences between RA and OA for known high-risk genetic polymorphisms.

Since the 1970s it has been known that variants in the HLA region on chromosome 6p21.3 are associated with RA [29]. In our study, the main effect to RA risk came from HLA-DRB1*04 allele. Additionally, we found protective effects of HLA-DRB1*07 and *13 in the whole study group. However, common SNP markers in genes PTPN22 and STAT4 also contributed to RA susceptibility, but no other SNPs analyzed. It is noteworthy, that, in contrast to other studies, STAT4 SNP rs7574865 showed higher significance than PTPN22 SNP rs2476601. One explanation may be our study design. By comparing RA with OA patients, genes with opposing effects will show higher OR.

For SNPs rs3761847 and rs10818488, localized between TRAF1 and C5 genes, we were not able to find a statistically significant association with RA. Recently, re-evaluation of RA susceptibility genes in the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium study revealed very moderate effect sizes for SNPs in the TRAF1/C5 genomic region (OR = 1.08) [30]. The effect of TRAF1/C5 alleles may have been over-estimated in the initial study ('winner's curse'). Therefore, in replication studies, the moderate effects have to be the basis for analysis.

The power to detect association in our study was only 12% (minor allele frequency = 39%, assumed OR = 1.08, one-tailed P = 0.05). Hence, both missing power and ethnicity could explain the non-replication of these associations with RA in our Slovak population. For example, minor allele frequency for rs10818488 in controls is lower in our study (0.39) compared with published data in sample sets from the Netherlands, Sweden, and the USA (0.44) [9]. Another reason could be the pathophysiological identity in genetic susceptibility between RA and OA. Our study is designed to work out specific genetic differences to RA susceptibility in comparison to OA. As a consequence, common pathways would not be highlighted as association signals. It is important to note that in a recent study, an association was found with RA in the extended genomic segment including TRAF1 but excluding the C5 coding region [31]. Therefore, more specific and potentially unlinked SNP markers may exist and should be taken into account.

We only found nominal significance for SNPs rs10499194 OLIG3/TNFAIP3 and rs6920220 OLIG3/TNFAIP3 , identified by Plenge and colleagues as independent RA risk markers [6]. The two SNPs are located on chromosome 6q23 and are in weak LD. SNP rs10499194 OLIG3/TNFAIP3 showed a pronounced effect on RA risk in a recessive model in our study sample (P = 0.014), and, hence, might need larger populations to be detected with study-wide significance. Interestingly, minor allele frequency for rs10499194 OLIG3/TNFAIP3 (0.315) is on the upper end whereas that for rs6920220 OLIG3/TNFAIP3 (0.154) is below the frequencies from previously published studies [6, 7]. Again, this may be caused by our study design or represent an ethnical characteristic. Perfect proxies of rs10499194 OLIG3/TNFAIP3 are also associated with a risk of systemic lupus erythematosus [32]. Therefore, this genomic region might contribute to risk for autoimmune diseases and needs to be analyzed in further studies with higher power to detect an effect.

We were not able to show an association between the six SNPs and RA in the male subset of our population, which was likely to be due to a lack of power. However, gender-specific influence on association signal can not be excluded. Recently, in the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium genome-wide association study, a single SNP (rs11761231) generated a strong signal in the gender-differentiated analyses for RA, with an additive effect in females and no effect in males [4]. In contrast, a protective effect of the HLA-DRB1*13 allele was obvious in our male subgroup with an OR of 0.32 (i.e. OR = 3.13 for susceptibility allele). One possible explanation is the moderate SNP OR between 1.38 and 1.67 in the whole sample and, therefore, a loss of power to detect this effect in the small male sample (87 cases, 60 controls).

Several limitations of our study have to be considered. The summarization of all HLA-DRB1*01xx and *04xx alleles as SE alleles ignored the protective effects of *0103 and *0402 and the neutral effect of *0403, *0406, and *0407 subtypes. However, a recent report by Morgan and colleagues showed that the frequency of these alleles is very low [20]. Therefore, we may have underestimated the risk effect of HLA-DRB1*01 and *04 alleles in this study but confirmed the association between HLA-DRB1*04 SE and RA.

Our RA population is heterogenous in relation to RF and anti-CCP. Another study showed that the HLA-DRB1 SE alleles are only associated with anti-CCP-positive RA in a European population, where the combination of smoking history and SE alleles increased the risk for RA 21-fold [33]. Here, we found significant association to RA risk for PTPN22 variant rs2476601 and HLA-DRB1 alleles in anti-CCP-positive RA patients compared with OA controls. Analysis within our RA group divided into anti-CCP-positive and anti-CCP-negative subgroups revealed a pattern of association for HLA-DRB1-alleles similar to that found in the unstratified case-control setting. It remains unclear whether we had too little power to detect other effects or in fact found a significant causal interaction between serum anti-CCP antibody, HLA-DRB1 alleles, and rs2476601 PTPN22 as previously described [33, 34].

The ascertainment strategy used here was not aimed at collecting special subgroups (e.g. only RF-positive RA cases with detectable anti-CCP) and, therefore, is not presenting a particular form of pathology with a higher power to detect specific genetic factors. However, this population reflects the clinical reality and, hence, allows a better risk assessment for the general patient with RA.

The predictive value of genetic markers for RA diagnosis is not obvious when using a limited number of alleles [35]. However, the knowledge of nearly all genetic variants contributing to both RA and OA susceptibility in a given ethnicity may help to prevent clinical mismanagement and avoid excessive costs. Our population is the first aimed at identifying genetic differences between RA and OA and, therefore, allowing the dissection of genetic markers for diagnosis in the border area between these two disease entities.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates strong evidence that polymorphisms in HLA-DRB1, PTPN22, and STAT4 genes contribute to RA susceptibility in a comprehensively characterized Slovak case population compared with a gender-matched OA control group.

Abbreviations

- CCP:

-

cyclic citrullinated peptide

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- ELISA:

-

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- HLA:

-

human leukocyte antigen

- LD:

-

linkage disequilibrium

- OA:

-

osteoarthritis

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- PCR:

-

polymerase chain reaction

- RA:

-

rheumatoid arthritis

- RF:

-

rheumatoid factor

- SE:

-

shared epitope

- SNP:

-

single nucleotide polymorphism.

References

Wordsworth P, Bell J: Polygenic susceptibility in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1991, 50: 343-346. 10.1136/ard.50.6.343.

McDaniel DO, Barger BO, Acton RT, Koopman WJ, Alarcon GS: Molecular analysis of HLA-D region genes in seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Tissue Antigens. 1989, 34: 299-308. 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1989.tb01746.x.

Bowes J, Barton A: Recent advances in the genetics of RA susceptibility. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008, 47: 399-402. 10.1093/rheumatology/ken005.

Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium: Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007, 447: 661-678. 10.1038/nature05911.

Remmers EF, Plenge RM, Lee AT, Graham RR, Hom G, Behrens TW, de Bakker PI, Le JM, Lee HS, Batliwalla F, Li W, Masters SL, Booty MG, Carulli JP, Padyukov L, Alfredsson L, Klareskog L, Chen WV, Amos CI, Criswell LA, Seldin MF, Kastner DL, Gregersen PK: STAT4 and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2007, 357: 977-986. 10.1056/NEJMoa073003.

Plenge RM, Cotsapas C, Davies L, Price AL, de Bakker PI, Maller J, Pe'er I, Burtt NP, Blumenstiel B, Defelice M, Parkin M, Barry R, Winslow W, Healy C, Graham RR, Neale BM, Izmailova E, Roubenoff R, Parker AN, Glass R, Karlson EW, Maher N, Hafler DA, Lee DM, Seldin MF, Remmers EF, Lee AT, Padyukov L, Alfredsson L, Coblyn J, et al: Two independent alleles at 6q23 associated with risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Genet. 2007, 39: 1477-1482. 10.1038/ng.2007.27.

Thomson W, Barton A, Ke X, Eyre S, Hinks A, Bowes J, Donn R, Symmons D, Hider S, Bruce IN, Wilson AG, Marinou I, Morgan A, Emery P, Carter A, Steer S, Hocking L, Reid DM, Wordsworth P, Harrison P, Strachan D, Worthington J: Rheumatoid arthritis association at 6q23. Nat Genet. 2007, 39: 1431-1433. 10.1038/ng.2007.32.

Plenge RM, Seielstad M, Padyukov L, Lee AT, Remmers EF, Ding B, Liew A, Khalili H, Chandrasekaran A, Davies LR, Li W, Tan AK, Bonnard C, Ong RT, Thalamuthu A, Pettersson S, Liu C, Tian C, Chen WV, Carulli JP, Beckman EM, Altshuler D, Alfredsson L, Criswell LA, Amos CI, Seldin MF, Kastner DL, Klareskog L, Gregersen PK: TRAF1-C5 as a risk locus for rheumatoid arthritis–a genomewide study. N Engl J Med. 2007, 357: 1199-1209. 10.1056/NEJMoa073491.

Kurreeman FA, Padyukov L, Marques RB, Schrodi SJ, Seddighzadeh M, Stoeken-Rijsbergen G, Helm-van Mil van der AH, Allaart CF, Verduyn W, Houwing-Duistermaat J, Alfredsson L, Begovich AB, Klareskog L, Huizinga TW, Toes RE: A candidate gene approach identifies the TRAF1/C5 region as a risk factor for rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS Med. 2007, 4: e278-10.1371/journal.pmed.0040278.

Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, Christy W, Cooke TD, Greenwald R, Hochberg M: Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum. 1986, 29: 1039-1049. 10.1002/art.1780290816.

Altman R, Alarcon G, Appelrouth D, Bloch D, Borenstein D, Brandt K, Brown C, Cooke TD, Daniel W, Gray R: The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hand. Arthritis Rheum. 1990, 33: 1601-1610. 10.1002/art.1780331101.

Altman R, Alarcon G, Appelrouth D, Bloch D, Borenstein D, Brandt K, Brown C, Cooke TD, Daniel W, Feldman D: The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hip. Arthritis Rheum. 1991, 34: 505-514. 10.1002/art.1780340502.

Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, Healey LA, Kaplan SR, Liang MH, Luthra HS: The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988, 31: 315-324. 10.1002/art.1780310302.

Miyamoto Y, Mabuchi A, Shi D, Kubo T, Takatori Y, Saito S, Fujioka M, Sudo A, Uchida A, Yamamoto S, Ozaki K, Takigawa M, Tanaka T, Nakamura Y, Jiang Q, Ikegawa S: A functional polymorphism in the 5' UTR of GDF5 is associated with susceptibility to osteoarthritis. Nat Genet. 2007, 39: 529-533. 10.1038/2005.

Martinez A, Varade J, Lamas JR, Fernandez-Arquero M, Jover JA, de la Concha EG, Fernandez-Gutierrez B, Urcelay E: GDF5 Polymorphism associated with osteoarthritis: risk for rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008, 67: 1352-1353. 10.1136/ard.2007.085050.

Stark K, Reinhard W, Neureuther K, Wiedmann S, Sedlacek K, Baessler A, Fischer M, Weber S, Kaess B, Erdmann J, Schunkert H, Hengstenberg C: Association of common polymorphisms in GLUT9 gene with gout but not with coronary artery disease in a large case-control study 5. PLoS ONE. 2008, 3: e1948-10.1371/journal.pone.0001948.

Olerup O, Zetterquist H: HLA-DR typing by PCR amplification with sequence-specific primers (PCR-SSP) in 2 hours: an alternative to serological DR typing in clinical practice including donor-recipient matching in cadaveric transplantation. Tissue Antigens. 1992, 39: 225-235. 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1992.tb01940.x.

Bodmer JG, Marsh SG, Albert ED, Bodmer WF, Bontrop RE, Dupont B, Erlich HA, Hansen JA, MacH B, Mayr WR, Parham P, Petersdorf EW, Sasazuki T, Schreuder GM, Strominger JL, Svejgaard A, Terasaki PI: Nomenclature for factors of the HLA System, 1998. Hum Immunol. 1999, 60: 361-395. 10.1016/S0198-8859(99)00042-7.

de Vries N, Tijssen H, van Riel PL, Putte van de LB: Reshaping the shared epitope hypothesis: HLA-associated risk for rheumatoid arthritis is encoded by amino acid substitutions at positions 67–74 of the HLA-DRB1 molecule. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 46: 921-928. 10.1002/art.10210.

Morgan AW, Haroon-Rashid L, Martin SG, Gooi HC, Worthington J, Thomson W, Barrett JH, Emery P: The shared epitope hypothesis in rheumatoid arthritis: evaluation of alternative classification criteria in a large UK Caucasian cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 58: 1275-1283. 10.1002/art.23432.

Wigginton JE, Cutler DJ, Abecasis GR: A note on exact tests of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Am J Hum Genet. 2005, 76: 887-893. 10.1086/429864.

Sasieni PD: From genotypes to genes: doubling the sample size. Biometrics. 1997, 53: 1253-1261. 10.2307/2533494.

Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, Sham PC: PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007, 81: 559-575. 10.1086/519795.

PLINK v1.04. [http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/plink/]

Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ: Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005, 21: 263-265. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457.

HaploView v4.1. [http://www.broad.mit.edu/mpg/haploview/]

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A: G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007, 39: 175-191.

G*Power 3.0.10. [http://www.psycho.uni-duesseldorf.de/abteilungen/aap/gpower3/]

Stastny P: Association of the B-cell alloantigen DRw4 with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 1978, 298: 869-871.

Barton A, Thomson W, Ke X, Eyre S, Hinks A, Bowes J, Gibbons L, Plant D, Wilson AG, Marinou I, Morgan A, Emery P, Steer S, Hocking L, Reid DM, Wordsworth P, Harrison P, Worthington J: Re-evaluation of putative rheumatoid arthritis susceptibility genes in the post-genome wide association study era and hypothesis of a key pathway underlying susceptibility. Hum Mol Genet. 2008, 17: 2274-2279. 10.1093/hmg/ddn128.

Chang M, Rowland CM, Garcia VE, Schrodi SJ, Catanese JJ, Helm-van Mil van der AH, Ardlie KG, Amos CI, Criswell LA, Kastner DL, Gregersen PK, Kurreeman FA, Toes RE, Huizinga TW, Seldin MF, Begovich AB: A large-scale rheumatoid arthritis genetic study identifies association at chromosome 9q33.2. PLoS Genet. 2008, 4: e1000107-10.1371/journal.pgen.1000107.

Musone SL, Taylor KE, Lu TT, Nititham J, Ferreira RC, Ortmann W, Shifrin N, Petri MA, Ilyas KM, Manzi S, Seldin MF, Gregersen PK, Behrens TW, Ma A, Kwok PY, Criswell LA: Multiple polymorphisms in the TNFAIP3 region are independently associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2008, 40: 1062-1064. 10.1038/ng.202.

Klareskog L, Stolt P, Lundberg K, Kallberg H, Bengtsson C, Grunewald J, Ronnelid J, Harris HE, Ulfgren AK, Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S, Eklund A, Padyukov L, Alfredsson L: A new model for an etiology of rheumatoid arthritis: smoking may trigger HLA-DR (shared epitope)-restricted immune reactions to autoantigens modified by citrullination. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54: 38-46. 10.1002/art.21575.

Padyukov L, Silva C, Stolt P, Alfredsson L, Klareskog L: A gene-environment interaction between smoking and shared epitope genes in HLA-DR provides a high risk of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 50: 3085-3092. 10.1002/art.20553.

Goeb V, Dieude P, Daveau R, Thomas-L'otellier M, Jouen F, Hau F, Boumier P, Tron F, Gilbert D, Fardellone P, Cornelis F, Le LX, Vittecoq O: Contribution of PTPN22 1858T, TNFRII 196R and HLA-shared epitope alleles with rheumatoid factor and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies to very early rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008, 47: 1208-1212. 10.1093/rheumatology/ken192.

Acknowledgements

Parts of this study were supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, Research Unit FOR696). We gratefully acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Birgit Riepl, Margit Nützel, Josef Simon, and Michaela Vöstner.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

KS carried out the SNP genotyping and statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. JR and SB collected the sample and phenotyped the patients. HGW and SF carried out the HLA typing. CH participated in study coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. RS conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

13075_2009_2539_MOESM1_ESM.doc

Additional file 1: Word file containing 18 tables. Table S1 lists the HLA-DRB1 allele classification. Table S2 lists the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) association results from different genetic models in rheumatoid arthritis (RA)- osteoarthritis (OA) case-control sample. Table S3 lists the SNP association analysis results in male RA case-control sample. Table S4 lists the SNP association analysis results in female RA-OA case-control sample. Table S5 lists the SNP association analysis results in RA patients with rheumatoid factor (RF) vs. RA patients without RF. Table S6 lists the SNP association analysis results in RA patients with RF vs. OA controls. Table S7 lists the SNP association analysis results in RA patients without RF vs. OA controls. Table S8 lists the SNP association analysis results in anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP)-positive RA patients vs. anti-CCP-negative RA patients. Table S9 lists the SNP association analysis results in anti-CCP-positive RA patients vs. anti-CCP-negative OA patients. Table S10 lists the SNP association analysis results in anti-CCP-negative RA patients vs. anti-CCP-negative OA patients. Table S11 lists the HLA-DRB1 association analysis results in male RA case-control sample. Table S12 lists the HLA-DRB1 association analysis results in female RA case-control sample. Table S13 lists the HLA-DRB1 association analysis results in RA patients with RF vs. RA patients without RF. Table S14 lists the HLA-DRB1 association analysis results in RA patients with RF vs. OA controls. Table S15 lists the HLA-DRB1 association analysis results in RA patients without RF vs. OA controls. Table S16 lists the HLA-DRB1 association analysis results in anti-CCP-positive RA patients vs. anti-CCP-negative RA patients. Table S17 lists the HLA-DRB1 association analysis results in anti-CCP-positive RA patients vs. anti-CCP-negative OA patients. Table S18 lists the HLA-DRB1 association analysis results in anti-CCP-negative RA patients vs. anti-CCP-negative OA patients. (DOC 166 KB)

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Stark, K., Rovenský, J., Blažičková, S. et al. Association of common polymorphisms in known susceptibility genes with rheumatoid arthritis in a Slovak population using osteoarthritis patients as controls. Arthritis Res Ther 11, R70 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2699

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2699