Abstract

Epidemiology is the study of the distribution and determinants of disease in human populations. Over the past decade there has been considerable progress in our understanding of the fundamental descriptive epidemiology (levels of disease frequency: incidence and prevalence, comorbidity, mortality, trends over time, geographic distributions, and clinical characteristics) of the rheumatic diseases. This progress is reviewed for the following major rheumatic diseases: rheumatoid arthritis (RA), juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, osteoarthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, giant cell arteritis, polymyalgia rheumatica, gout, Sjögren's syndrome, and ankylosing spondylitis. These findings demonstrate the dynamic nature of the incidence and prevalence of these conditions – a reflection of the impact of genetic and environmental factors. The past decade has also brought new insights regarding the comorbidity associated with rheumatic diseases. Strong evidence now shows that persons with RA are at a high risk for developing several comorbid disorders, that these conditions may have atypical features and thus may be difficult to diagnose, and that persons with RA experience poorer outcomes after comorbidity compared with the general population. Taken together, these findings underscore the complexity of the rheumatic diseases and highlight the key role of epidemiological research in understanding these intriguing conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Epidemiology has taken an important role in improving our understanding of the outcomes of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and other rheumatic diseases. Epidemiology is the study of the distribution and determinants of disease in human populations. This definition is based on two fundamental assumptions. First, human disease does not occur at random; and second, human disease has causal and preventive factors that can be identified through systematic investigation of different populations or subgroups of individuals within a population in different places or at different times. Thus, epidemiologic studies include simple descriptions of the manner in which disease appears in a population (levels of disease frequency: incidence and prevalence, comorbidity, mortality, trends over time, geographic distributions, and clinical characteristics) and studies that attempt to quantify the roles played by putative risk factors for disease occurrence. Over the past decade considerable progress has been made in both types of epidemiologic studies. The latter studies are the topic of Professor Silman's review in this special issue of Arthritis Research & Therapy [1]. In this review we examine a decade of progress on the descriptive epidemiology (incidence, prevalence, and survival) associated with the major rheumatic diseases. We then discuss the influence of comorbidity on the epidemiology of rheumatic diseases, using RA as an example.

The epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis

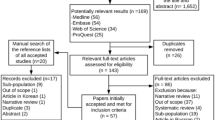

The most reliable estimates of incidence, prevalence, and mortality in RA are those derived from population-based studies [2–6]. Several of these, primarily from the past decade, have been conducted in a variety of geographically and ethnically diverse populations [7]. Indeed, a recent systematic review of the incidence and prevalence of RA [8] revealed substantial variation in incidence and prevalence across the various studies and across time periods within the studies. These data emphasize the dynamic nature of the epidemiology of RA. A substantial decline in RA incidence over time, with a shift toward a more elderly age of onset, was a consistent finding across several studies. Also notable was the virtual absence of epidemiologic data for the developing countries of the world.

Data from Rochester (Minnesota, USA) demonstrate that although the incidence rate fell progressively over the four decades of study – from 61.2/100,000 in 1955 to 1964, to 32.7/100,000 in 1985 to 1994 – there were indications of cyclical trends over time (Figure 1) [9]. Moreover, data from the past decade suggest that RA incidence (at least in women) appears to be rising after four decades of decline [10].

Annual incidence of rheumatoid arthritis in Rochester, Minnesota. Shown is the annual incidence rate per 100,000 population by sex: 1955 to 1995. Each rate was calculated as a 3-year centered moving average. Reproduced from [9] with permission.

Several studies in the literature provide estimates of the number of people with current disease (prevalence) in a defined population. Although these studies suffer from a number of methodological limitations, the remarkable finding across these studies is the uniformity of RA prevalence rates in developed populations – approximately 0.5% to 1% of the adult population [11–18].

Mortality

Mortality, the ultimate outcome that may affect patients with rheumatic diseases, has been positively associated with RA and RA disease activity since 1953, although the physician community has only recognized this link in recent years. Over the past decade, research on mortality in RA and other rheumatic diseases has gained momentum. These studies have consistently demonstrated an increased mortality in patients with RA when compared with expected rates in the general population [9, 13, 19–23]. The standardized mortality ratios varied from 1.28 to 2.98, with primary differences being due to method of diagnosis, geographic location, demographics, study design (inception versus community cohorts), thoroughness of follow up, and disease status [23–26]. Population-based studies specifically examining trends in mortality over time have concluded that the excess mortality associated with RA has remained unchanged over the past two to three decades [19]. Although some referral-based studies have reported an apparent improvement in survival, a critical review indicated that these observations are likely due to referral selection bias [26].

Recent studies have demonstrated that RA patients have not experienced the same improvement in survival as the general population, and therefore the mortality gap between RA patients and individuals without RA has widened (Figure 2) [25]. The reasons for this widening mortality gap are unknown. Recent data (Figure 3) [27] suggest a trend toward an increase in RA-associated mortality rates in the older population groups.

Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis by sex. Observed mortality in (a) female and (b) male patients with rheumatoid arthritis and expected mortality (based on the Minnesota white population). Observed is solid line, expected is dashed line, and the gray region represents the 95% confidence limits for observed. Reproduced from [25] with permission.

Age-specific mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Age-specific mortality rates (per 100,000) for women with rheumatoid arthritis (death certificates with any mention of rheumatoid arthritis). Reproduced from [27] with permission.

Nonetheless, new treatments that dramatically reduce disease activity and improve function should result in improved survival. Since 2006, only methotrexate has shown an effect on RA mortality, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.4 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.2 to 0.8), although lesser powered studies have recently hinted at a similar effect of anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) treatment [7, 16, 28, 29].

A number of investigators have examined the underlying causes for the observed excess mortality in RA [30]. These reports suggest increased risk from cardiovascular, infectious, hematologic, gastrointestinal, and respiratory diseases among RA patients compared with control individuals. Various disease severity and disease activity markers in RA (for example, extraarticular manifestations, erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], seropositivity, higher joint count, and functional status) have also been shown to be associated with increased mortality [31–33].

The epidemiology of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

A number of studies have examined the epidemiology of chronic arthritis in childhood [34–36]. Oen and Cheang [34] conducted a comprehensive review of descriptive epidemiology studies of chronic arthritis in childhood and analyzed factors that may account for differences in the reported incidence and prevalence rates. As this review illustrates, the large majority of available studies are clinic-based and thus are susceptible to numerous biases. The few population-based estimates available indicate that the prevalence of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) is approximately 1 to 2 per 1,000 children, and the incidence is 11 to 14 new cases per 100,000 children.

The review by Oen and Cheang [34] revealed that reports of the descriptive epidemiology of chronic arthritis in childhood differ in methods of case ascertainment, data collection, source population, geographic location, and ethnic background of the study population. This analysis further demonstrated that the use of different diagnostic criteria had no effect on the reported incidence or prevalence rates. The strongest predictors of disease frequency were source population (with the highest rates being reported in population studies and the lowest in clinic-based cohorts) and geographic origin of the report. The former is consistent with more complete case ascertainment in population-based studies compared with clinic-based studies, whereas the latter suggests possible environmental and/or genetic influences in the etiology of juvenile chronic arthritis.

A review in 1999 [37] concurred that the variations in incidence over time indicate environmental influences whereas ethnic and familial aggregations suggest a role for genetic factors. The genetic component of juvenile arthritis is complex, probably involving the effects of multiple genes. The best evidence pertains to certain human leukocyte antigen (HLA) loci (HLA-A, HLA-DR/DQ, and HLA-DP), but there are marked differences according to disease subtype [38, 39]. Environmental influences are also suggested by studies that demonstrated secular trends in the yearly incidence of JRA, and a seasonal variation in systemic JRA was documented [36, 40–42].

Various studies examined long-term outcomes of JRA [43–45]. Adults with a history of JRA have been shown to have a lower life expectancy than members of the general population of the same age and sex. Over 25 years of follow up of a cohort of 57 adults with a history of RA [46], the mortality rate among JRA cases was 0.27 deaths per 100 years of patient follow up, as compared with an expected mortality rate of 0.068 deaths per 100 years of follow up in the general population. All deaths were associated with autoimmune disorders. In another study, a clinic-based cohort of 215 juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients was followed up for a median of 16.5 years [47]. The majority of the patients had a favorable outcome and no deaths were observed. Half of the patients had low levels of disease activity and few physical signs of disease (for example, tender swollen joints, restrictions in joint motion, and local growth disturbances). Ocular involvement was the most common extra-articular manifestation, affecting 14% of the patients.

The epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis

Five studies have provided data on the incidence of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) [48–50]. Kaipiainen-Seppanen and Aho [51] examined all patients who were entitled under the nationwide sickness insurance scheme to receive specially reimbursed medication for PsA in Finland in the years 1990 and 1995. A total of 65 incident cases of PsA were identified in the 1990 study, resulting in an annual incidence of 6 per 100,000 of the adult population aged 16 years or older. The mean age at diagnosis was 46.8 years, with the peak incidence occurring in the 45 to 54 year age group. There was a slight male to female predominance (1.3:1). Incidence in 1995 was of the same order of magnitude, at 6.8 per 100,000 (95% CI = 5.4 to 8.6). The incidence in southern Sweden was reported to be similar to that in Finland [48].

A study by Shbeeb and coworkers [49] from Olmsted County (Minnesota, USA) used the population-based data resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project to identify all cases of inflammatory arthritis associated with a definite diagnosis of psoriasis. Sixty-six cases of PsA were first diagnosed between 1982 and 1991. The average age- and sex-adjusted incidence rate per 100,000 was 6.59 (95% CI = 4.99 to 8.19), a rate remarkably similar to that reported in the Finnish study [51]. The average age at diagnosis was 40.7 years. At diagnosis 91% of cases had oligoarthritis. Over the 477.8 person-years of follow up, only 25 patients developed extra-articular manifestations, and survival was not significantly different from that in the general population. The prevalence rate on 1 January 1992 was 1 per 1,000 (95% CI = 0.81 to 1.21). The US study [49] reported a higher prevalence rate and lower disease severity than the other studies. These differences may be accounted for by differences in the case definition and ascertainment methods. Although the Finnish cohort was population based, the ascertainment methods in that study relied on receipt of medication for PsA. Thus, mild cases not requiring medication may not have been identified in the Finnish cohort.

Gladman and colleagues [52–54] have reported extensively on the clinical characteristics, outcomes, and mortality experiences of large groups of patients with PsA seen in a single tertiary referral center. The results of these studies differ from those of the population-based analyses in that they demonstrate significantly increased mortality and morbidity among patients with PsA compared with the general population. However, because all patients in these studies are referred to a single outpatient tertiary referral center, these findings could represent selection referral bias. Clearly, additional population-based data are needed to resolve these discrepancies.

A recent population-based study of the incidence of PsA [55] reported the overall age- and sex-adjusted annual incidence of PsA per 100,000 to be 7.2 (95% CI = 6.0 to 8.4; Figure 4). The incidence was higher in men (9.1, 95% CI = 7.1 to 11.0) than in women (5.4, 95% CI = 4.0 to 6.9). The age- and sex-adjusted annual incidence of PsA per 100,000 increased from 3.6 (95% CI = 2.0 to 5.2) between 1970 and 1979, to 9.8 (95% CI = 7.7 to 11.9) between 1990 and 2000 (P for trend < 0.001), providing the first evidence that the incidence of psoriasis increased during recent decades. The point prevalence per 100,000 was 158 (95% CI = 132 to 185) in 2000, with a higher prevalence in men (193, 95% CI = 150 to 237) than in women (127, 95% CI = 94 to 160). The reasons for the increase remain unknown.

Annual incidence of psoriatic arthritis by age and sex. Shown is the annual incidence (per 100,000) of psoriatic arthritis by age and sex (1 January 1970 to 31 December 1999; Olmsted County, Minnesota). Broken lines represent smoothed incidence curves obtained using smoothing splines. Reproduced from [55] with permission.

The epidemiology of osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common form of arthritis, affecting every population and ethnic group investigated thus far. Although OA is most common in elderly populations, reported prevalence values have a wide range because they depend on the joint(s) involved (for example, knee, hip, and hand) as well as the diagnosis used in the study (for instance, radiographic, symptomatic, and clinical). Oliveria and colleagues [56] illustrated this variation in symptomatic OA incidence by sex and joint over time (Figure 5). Recently, Murphy and coworkers [57] reported the lifetime risk for symptomatic knee OA to be 44.7% (95% CI = 48.4% to 65.2%). Increasing age, female sex, and obesity are primary risk factors for developing OA.

Incidence of osteoarthritis by joint. Shown is the incidence of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee in members of the Fallon Community Health Plan, 1991 to 1992, by age and sex. Reproduced from [56] with permission.

OA accounts for more dependency in walking, stair climbing, and other lower extremity tasks than any other disease [58]. Recently, Lawrence and colleagues [59] estimated that 26.9 million Americans aged 25 or older had clinical OA of some joint. The economic impact of OA, both in terms of direct medical costs and lost wages, is impressive [60, 61]. In 2005, hospitalizations for musculoskeletal procedures in the USA, which were predominantly knee arthroplasties and hip replacements, totaled $31.5 billion or more than 10% of all hospital care [62]. This highlights the dramatic increase in societal costs and burden of OA, because only 10 years earlier the entire cost of OA in the USA was estimated at $15.5 billion dollars (1994 dollars) [63]. Given that preventive interventions and therapeutic options for OA are limited, we can expect the morbidity and economic impact of OA to increase with the aging of the developed world.

The epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus

A population-based study examined the incidence and mortality of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in a geographically defined population over a 42-year period [64]. These findings indicate that, over the past 4 decades, the incidence of SLE has nearly tripled and that the survival rate for individuals with this condition (while still poorer than expected for the general population) has significantly improved. The average incidence rate (age- and sex-adjusted to the 1970 US white population) was 5.56 per 100,000 (95% CI = 3.93 to 7.19) during the period from 1980 to 1992, as compared with an incidence of 1.51 (95% CI = 0.85 to 2.17) during the period from 1950 to 1979. These results compare favorably with previously reported SLE incidence rates of between 1.5 and 7.6 per 100,000. In general, studies reporting higher incidence rates utilized more comprehensive case retrieval methods. The reported prevalence of SLE has also varied significantly. One study reported an age- and sex-adjusted prevalence, as of 1 January 1992, of approximately 122 per 100,000 (95% CI = 97 to 147) [64]. This prevalence is higher than other reported prevalence rates in the continental USA, which have ranged between 14.6 and 50.8 per 100,000 [65]. However, two studies of self-reported diagnoses of SLE indicated that the actual prevalence of SLE in the USA may be much higher than previously reported [66]. One of these studies validated the self-reported diagnoses of SLE by reviewing available medical records [66], revealing a prevalence of 124 cases per 100,000.

There is good evidence that survival in SLE patients has improved significantly over the past four decades [67].

Explanations for the improved survival included earlier diagnosis of SLE, recognition of mild disease, increased utilization of anti-nuclear antibody testing, and better approaches to therapy. Walsh and DeChello [68] demonstrated considerable geographic variation in SLE mortality within the USA. Although it is difficult to distinguish between whether the observed variation reflects clustering of risk factors for SLE or regional differences in diagnosis and treatment, there is a clear pattern of elevated mortality in clusters with high poverty rates and greater concentrations of ethnic Hispanic patients versus those with lower mortality. Moreover, although improvements in survival have also been demonstrated in some Asian and African countries, these are not as significant as in the USA [69, 70].

The epidemiology of giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica

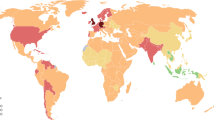

Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) and giant cell arteritis (GCA) are closely related conditions [71]. Numerous studies have been conducted that describe the epidemiology of PMR and GCA in a variety of population groups. As shown in Additional file 1, GCA appears to be most frequent in the Scandinavian countries, with an incidence rate of approximately 27 per 100,000 [72] and in the northern USA, with an incidence rate of approximately 19 per 100,000 [73], as compared with southern Europe and the southern USA, where the reported incidence rates have been approximately 7 per 100,000. Such remarkable differences in incidence rates according to geographic variation and latitude are suggestive of a common environmental exposure. Nonetheless, these differences do not rule out common genetic predisposition.

The average annual age- and sex-adjusted incidence of PMR per 100,000 population aged 50 years or older has been estimated at 58.7 (95% CI = 52.8 to 64.7), with a significantly higher incidence in women (69.8; 95% CI = 61.2 to 78.4) than in men (44.8; 95% CI = 37.0 to 52.6) [74]. The prevalence of PMR among persons older then 50 years on 1 January 1992 has been estimated at 6 per 1,000. The incidence rate in Olmsted County (58.7/100,000) is similar to that reported in a Danish County (68.3 per 100,000), but is somewhat higher than that reported in Goteborg, Sweden (28.6/100,000), in Reggio Emilia, Italy (12.7/100,000) and Lugo, Spain (18.7/100,000) [75].

Secular trends in incidence rates can provide important etiologic clues. Two studies have examined secular trends in the incidence of GCA/PMR. Nordborg and Bengtsson [76] from Goteberg, Sweden, examined trends in the incidence of GCA between 1977 and 1986, and showed a near doubling of the incidence rate over this time period, particularly in females. Data from Olmsted County have also shown important secular trends in the incidence of GCA [73]. The annual incidence rates increased significantly from 1970 to 2000 and appeared to have clustered in five peak periods, which occurred about every 7 years. A significant calendar-time effect was identified, which predicted an increase in incidence of 2.6% (95% CI = 0.9% to 4.3%) every 5 years [73]. Similarly, Machado and coworkers [77] demonstrated an increase in incidence rates between 1950 and 1985. Notably, these secular trends were quite different in women, in whom the rate increased steadily over the time period, as compared with men, in whom the rate increased steadily from 1950 to 1974 and then began to decline during the late 1970s and early 1980s. The same finding of different secular trends, according to sex, were also observed in the Swedish study [76].

Such secular trends may be the result of increased recognition of that disease. In fact, there have been reports demonstrating that the observed frequency of classic disease manifestations in patients with a subsequent diagnosis of GCA is actually declining. This suggests that awareness of the less typical manifestations has improved, resulting in the diagnosis of previously unrecognized cases. However, if improved diagnosis were the only factor accounting for the increase in incidence rate, then comparable changes in both sexes would have been expected. This was not so.

The epidemiology of gout

Until relatively recently there have been very few studies on the epidemiology of gout. In 1967, a study using the Framingham data reported the prevalence of gout at 1.5% (2.8% in men and 0.4% in women) [78]. In England, Currie [79] reported the prevalence of gout to be 0.26% in 1975, and a multicenter study [80] reported the prevalence to be 0.95% in 1995. Various studies revealed that both gout and hyperuricemia have been increasing in the USA, Finland, New Zealand, and Taiwan [81–84]. The most recent study of the incidence of gout was a longitudinal cohort study of 1,337 eligible medical students who received a standardized medical examination and questionnaire during medical school [85]. Sixty cases (47 primary and 13 secondary) were identified among the 1,216 men included in the study. None occurred among the 121 women in the study. The cumulative incidence of all gout was 8.6% among men (95% CI = 5.9% to 11.3%). Body mass index at age 35 years (P = 0.01), excessive weight gain (>1.88 kg/m2) between cohort entry and age 35 years (P = 0.007), and the development of hypertension (P = 0.004) were significant risk factors for the development of gout in univariate analyses. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models confirmed the association of body mass index at age 35 years (relative risk [RR] = 1.12; P = 0.02), excessive weight gain (RR = 2.07; P = 0.02), and hypertension (RR = 3.26; P = 0.002) as risk factors for all gout. Recent studies have reported the prevalence of gout in the UK and Germany to be 1.4% during the years 2000 to 2005, and highlight the importance of comorbidities (obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and hypertension) [86, 87]

The epidemiology of Sjögren's syndrome

There have been very few studies performed describing the epidemiology of Sjögren's syndrome and keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Moreover, interpretation of existing studies is complicated by differences in the definition and application of diagnostic criteria. In a population-based study from Olmsted County, Minnesota, the average annual age- and sex-adjusted incidence of physician-diagnosed Sjögren's syndrome per 100,000 population was estimated to be 3.9 (95% CI = 2.8 to 4.9), with a significantly higher incidence in women (6.9; 95% CI = 5.0 to 8.8) than in men (0.5; 95% CI = 0.0 to 1.2) [88].

The prevalence of dry eyes or dry mouth and of primary Sjögren's syndrome among 52- to 72-year-old residents of Malmo, Sweden, according to the Copenhagen criteria, were established in 705 randomly selected individuals who answered a simple questionnaire. The calculated prevalence for the population of keratoconjunctivitis sicca was 14.9% (95% CI = 7.3% to 22.2%), of xerostomia 5.5% (95% CI = 3.0% to 7.9%), and of autoimmune sialoadenitis and primary Sjögren's syndrome 2.7% (95% CI = 1.0% to 4.5%). The Hordaland Health Study in Norway reported that the prevalence of primary Sjögren's syndrome was approximately seven times higher in the elderly population (age 71 to 74 years) compared with individuals aged 40 to 44 years [89]. In a Danish study, the frequency of keratoconjunctivitis sicca in persons age 30 to 60 years was estimated at 11%, according to the Copenhagen criteria, and the frequency of Sjögren's syndrome in the same age group was estimated to be between 0.2% and 0.8% [90]. In another study from China [91], the prevalence was 0.77% using Copenhagen criteria and 0.33% using the San Diego criteria. Two studies from Greece and Slovenia reported prevalences of 0.1% and 0.6%, respectively [92], whereas a Turkish study estimated the prevalence of Sjögren's syndrome at 1.56% [93, 94]. Sjögren's syndrome has also been reported to be associated with other rheumatic and autoimmune conditions, including fibromyalgia, autoimmune thyroid disease, multiple sclerosis, and spondyloarthropathy, as well as several malignancies, especially non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The epidemiology of ankylosing spondylitis

Two large population-based studies provided estimates of the incidence and prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis [95, 96]. Using the population-based data resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project, Carbone and coworkers [95] determined the incidence and prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis first diagnosed between 1935 and 1989 among residents of Rochester. The overall age- and sex-adjusted incidence was 7.3 per 100,000 person years (95% CI = 6.1 to 8.4). This incidence rate tended to decline between 1935 and 1989; however, there was little change in the age at symptom onset or at diagnosis over the 55-year study period. Overall survival was not decreased up to 28 years after diagnosis. Using the population-based data resources of the Finland sickness insurance registry, Kaipiainen-Seppanen and coworkers [51, 96] estimated the annual incidence of ankylosing spondylitis requiring antirheumatic medication to be 6.9 per 100,000 adults (95% CI = 6.0 to 7.8) with no change over time. They reported a prevalence of 0.15% (95% CI = 0.08% to 0.27%). Together, these findings indicate that there is constancy in the epidemiologic characteristics of ankylosing spondylitis.

The incidence and prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis has also been studied in various populations. The incidence of ankylosing spondylitis was shown to be relatively stable in northern Norway over 34 years at 7.26 per 100,000 [97]. Prevalence varied from 0.036% to 0.10%. In Greece and Japan, the incidence and prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis were significantly lower [98–101]. The incidence mirrors the prevalence of HLA-B27 seropositivity. HLA-B27 is present throughout Eurasia, but is virtually absent among the genetic unmixed native populations of South America, Australia, and in certain regions of equatorial and southern Africa. It has a very high prevalence among the native peoples of the circumpolar arctic and the subarctic regions of Eurasia and North America and in some regions of Melanesia. The prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis and the spondyloarthropathies is known to be very high in certain North American Indian populations [102, 103].

The role of comorbidity in determining outcome in the rheumatic diseases: the example of rheumatoid arthritis

What is comorbidity and why is it important?

A comorbid condition is a medical condition that co-exists along with the disease of interest, for example RA. Comorbidity can be further defined in terms of a current or past condition. It may represent an active, past, or transient illness. It may be linked to the rheumatic disease process itself and/or its treatment, or it may be completely independent of these (Table 1).

Because of these links, comorbidities have grown in importance to physicians and researchers because they greatly influence the patient's quality of life, the effectiveness of treatment, and the prognosis of the primary disease. The average RA patient has approximately 1.6 comorbidities [104], and the number increases with the patient's age. As may be expected, the more comorbidities a patient has, the greater the utilization of health services, the greater societal and personal costs, the poorer the quality of life, and the greater chances of hospitalization and mortality. Moreover, comorbidity adds considerable complexity to patient care, making diagnosis and treatment decisions more challenging. For example, myocardial infarction (MI) is much more likely to be silent among persons with diabetes mellitus or RA, than in the absence of those comorbidities. The outcome of MI or heart failure is worse among individuals with RA or diabetes mellitus. In addition, the more comorbid illnesses one has, the greater the interference with treatment and the greater the medical costs, disability, and risk for mortality. Therefore, it is important to recognize such illnesses and to account for them in the care of the individual patient.

RA outcomes include mortality, hospitalization, work disability, medical costs, quality of life, and happiness, among others. Different comorbid conditions influence such outcomes differently [105]. For example, pulmonary and cardiac comorbidity are most often associated with mortality, but work disability is more strongly associated with depression. Therefore, when we speak of comorbidity and its effect on prognosis, we need to define which outcome is of greatest interest.

Current interest in comorbidity also springs from the desire to understand causal pathological associations. For example, the documentation that cardiovascular diseases are increased in persons with RA, after controlling for cardiac risk factors [106], provides a basis for the understanding of the effect of RA inflammation on cardiac disease.

Comorbidity in rheumatoid arthritis

Cardiovascular diseases

Much recent literature has demonstrated that the excess mortality in persons with RA is largely attributable to cardiovascular disease [107]. The most common cardiovascular disease is ischemic heart disease. Research has repeatedly demonstrated that the risk for ischemic heart disease is significantly higher among persons with RA than in control individuals [108–115]. A recent population-based study of RA and comparable non-RA subjects showed that those with RA are at a 3.17-fold higher risk for having had a hospital MI (multivariable odds ratio = 3.17, 95% CI = 1.16 to 8.68) and a nearly 6-fold increased risk for having had a silent MI (multivariable odds ratio = 5.86, 95% CI = 1.29 to 26.64) [108]. These data also demonstrated that the cumulative incidence of silent MI and of sudden death after incidence/index date continue to rise over time (Figures 6 and 7).

Incidence of silent myocardial infarction: RA versus non-RA. Shown is the cumulative incidence of silent myocardial infarction in a population-based incidence cohort of 603 RA patients and a matched non-RA comparison group of 603 non-RA individuals from the same underlying population. Reproduced from [108] with permission.

Incidence of sudden cardiac death: RA versus non-RA. Shown is the cumulative incidence of sudden cardiac death in a population-based incidence cohort of 603 rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients and a matched non-RA comparison group from the same underlying population. Reproduced from [108] with permission.

In contradistinction, the same study reported that both the prevalence of angina pectoris at incidence/index date as well as the cumulative risk for angina pectoris after 30 years of follow up are significantly lower in persons with RA compared with the general population [108].

An emerging body of literature now indicates that persons with RA are also at increased risk for heart failure. The cumulative incidence of heart failure defined according to Framingham Heart Study criteria [116] after incident RA has been shown to be statistically significantly higher in persons with RA than in those without the disease in a population-based setting [117] (Figure 8).

Incidence of congestive heart failure: RA versus non-RA. Shown is a comparison of the cumulative incidence of congestive heart failure in the rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and non-RA cohort, according to years since index date, adjusting for the competing risk for death. Reproduced from [117] with permission.

At any particular age, the incidence of heart failure in RA patients was approximately twice that in non-RA individuals. Data from multivariable Cox models showed that RA subjects had about twice the risk for developing heart failure and that this risk changed little after accounting for the presence of ischemic heart disease, other risk factors, and the combination of these [117].

In subset analyses, this risk appeared to be largely confined to rheumatoid factor-positive RA cases. Indeed, rheumatoid factor-positive RA patients had a risk for developing heart failure that was 2.5 times higher than that in non-RA individuals – an excess risk very similar to that experienced by persons with diabetes mellitus.

Davis and colleagues [118] examined the presentation of heart failure in RA compared with that in the general population. They reported that RA patients with heart failure presented with a different constellation of signs and symptoms than non-RA individuals with heart failure. In particular, RA patients with heart failure were less likely to be obese or hypertensive, or to have had a history of ischemic heart disease. Moreover, the proportion of RA patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (≥ 50%) was significantly higher compared with non-RA individuals with heart failure (58.3% versus 41.4%; P = 0.02). Mean ejection fraction was also shown to be higher among RA patients than in non-RA individuals (50% versus 43%, P = 0.007).

Indeed, the likelihood of preserved ejection fraction at the onset of heart failure was 2.57 times greater in heart failure patients with RA than in those without RA (odds ratio = 2.57, 95% CI = 1.20 to 5.49). Other investigators also reported that heart failure is more common in persons with RA, and a number of echocardiographic series have reported preserved ejection fraction and/or diastolic functional impairment in persons with RA [119–121].

In summary, persons with RA appear to have an increased risk of both ischemic heart disease and heart failure. These comorbid conditions may present in an atypical fashion, making diagnosis and management challenging.

Malignancy

After cardiovascular disease, cancer is the second most common cause of mortality in RA patients. Figure 9 shows the standardized incidence rates (SIRs) from 13 recent studies during the past decade in a meta-analysis [122]. The overall SIR of nonskin cancer malignancy in RA is estimated to be 1.05 (95% CI = 1.01 to 1.09). Although the risk appears to be slightly increased in persons with RA, this increase appears to be due to only a few specific malignancies: lymphoma, lung cancer, and skin cancer. It is also possible that some cancers may actually have a decreased risk.

Relative risks for overall malignancies in RA patients versus general population. *Excluding nonmelanoma skin. †All solid tumors. ‡Excluding lymphatic and hematopoietic. CI, confidence interval; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; MTX, methotrexate; n, number of malignancies; N, population size; SIR, standardized incidence ratio; TNF, tumor necrosis factor. For original references see Smitten and coworkers [122].

Baeckland and coworkers [123] showed that lymphoma is not only increased in RA but also is related to the severity of the disease itself. Combining six recent studies, the analysis reported by Smitten and coworkers [122] determined the SIR of lymphoma to be 2.08 (95% CI = 1.80 to 2.39) in RA.

Recent research has linked smoking exposure to increased incidence of developing RA [124, 125]. After examining 12 recent studies, Smitten and coworkers [122] reported an SIR of 1.63 (95% CI = 1.43 to 1.87) for lung cancer in RA. This increase in lung cancer is probably related, at least in part, to the excess risk for smoking related to RA [126].

After lung cancer, breast cancer is the second most common cause of cancer among RA patients. Most studies show rates of breast cancer to be decreased among RA patients. Smitten and coworkers [122] summarized nine recent studies with an estimated SIR of 0.84 (95% CI = 0.79 to 0.90). The mechanism for this reduction is not understood, although James [127] hypothesizes that estrogen changes in RA may be a factor.

The risk for colorectal cancer has also been reported to be decreased in RA, with Smitten and coworkers [122] reporting an SIR of 0.77 (95% CI = 0.65 to 0.90) based on data summarized from 10 studies. This effect is hypothesized to be a result of the prostaglandin production due to the high use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and cyclo-oxygenase (COX)-2 selective inhibitors in RA patients.

Because skin cancer is relatively common and is often misdiagnosed, it has been difficult to determine the effect of RA on development of this cancer. Chakravarty and coworkers [128] identified an association between RA and nonmelanoma skin cancer, and Wolfe and Michaud [129] found an association between RA biologic treatment with an increased risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer (odds ratio = 1.5, 95% CI = 1.2 to 2.8) and melanoma (odds ratio = 2.3, 95% CI = 0.9 to 5.4).

Lung disease

Pulmonary infection is a major cause of death in RA. Infections may arise de novo, as in people without RA, or it might be facilitated by impaired immunity or underlying interstitial lung disease (ILD). The rate of ILD in RA varies with the method of ascertainment, and prospective studies have reported prevalence values ranging from 19% to 44% [130]. The prevalence of lung fibrosis and 'RA lung', as reported to patients by their physicians, has been estimated at 3.3% [131]. This estimate is in line with the 1% to 5% rate reported on chest radiographs among RA patients [130]. When assessed in 150 unselected consecutive patients with RA by high-resolution computed tomography, however, 19% were found to have fibrosing alveolitis [130]. These authors noted that if other prospective studies of ILD were combined using a common definition, the average prevalence would be 37% [132–134]. Many cases of ILD remain undetected or may be mild or even asymptomatic. However, once patients are symptomatic with ILD, there is a high mortality rate [135, 136]. ILD in RA may be different from 'usual' ILD, including differences in CD20+ B-cell infiltrates that imply 'a differential emphasis of B cell-mediated mechanisms'. Computed tomography findings also differ for RA and non-RA ILD [137].

The cause of ILD in persons with RA is not known. However, almost all disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs have been linked to lung disease and/or ILD, including injectable gold, penicillamine [138, 139], sulfasalazine [140], methotrexate [141–143], infliximab [144, 145], and leflunomide [146], with some reports linking infliximab to rapidly progressive and/or fatal ILD [147, 148].

Infection

Like other inflammatory disorders, RA appears to increase the risk for bacterial, tubercular, fungal, opportunistic, and viral infections, with all infections being more common in more active and severe RA [149]. The use of corticosteroids, and in some studies anti-TNF therapy, increases the risk for infection [150, 151]. In nonrandomized trials and observational studies, patients with severe RA are more likely to receive these therapies, thereby confounding the effect of RA and RA treatment. This channeling bias might explain a proportion of the observed increase in infections.

Before the methotrexate and anti-TNF era, studies showed a general increase in mortality due to infection in RA patients [152–155]. In a recent study from an inception cohort of 2,108 patients with inflammatory polyarthritis from a community-based registry followed up annually (median 9.2 years), the incidence of infection was more than two and a half times that of the general population. History of smoking, corticosteroid use, and rheumatoid factor were found to be significant independent predictors of infection-related hospitalization [156].

Corticosteroid use is associated with increased risk of serious bacterial infection [150, 151, 156–159]. The data with regard to anti-TNF therapy and infection is complex. Results of randomized trials indicate increased risk for infection [144, 160]. In addition, some studies show increased risk in the community associated with anti-TNF therapy [159], whereas other studies do not [151, 158, 161]. Among 2,393 RA patients followed in an administrative database, the multivariable-adjusted risk for hospitalization with a physician-confirmed definite bacterial infection was approximately twofold higher overall and fourfold higher during the first 6 months among patients receiving TNF-α antagonists versus those receiving methotrexate alone [159]. However, RA-based cohorts show no such increase, although some have reported an early increase in infection rate followed by a later decrease [151, 158, 161].

Tuberculosis (TB) appears to be increased in RA patients independent of treatment [162–167], although one US study differed in this regard [168]. Anti-TNF therapy substantially increases the risk for TB, notably in patients treated with infliximab [164–169]. Use of prednisone in doses of less than 15 mg/day was associated with an odds ratio for TB of 2.8 (95% CI = 1.0 to 7.9) in the UK General Practice Research Database [170]. Even with chemoprophylaxis, patients remain at high risk for developing active TB [171, 172].

There are few data with respect to viral infections. In general, there is an increased risk of herpes zoster in RA patients [173]. However, this risk is not increased in RA relative to OA, and is strongly linked to functional status as measured by the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HR = 1.3 in both groups) [174]. In this study, cyclophosphamide (HR = 4.2), azathioprine (HR = 2.0), prednisone (HR = 1.5), leflunomide (HR = 1.4), and COX-2 selective NSAIDs (HR = 1.3) were all significant predictors of herpes zoster risk [174] Controlling for RA severity, there appears no significant increased risk for herpes zoster due to methotrexate or general anti-TNF therapy [174, 175], but there is new evidence of an effect due to monoclonal anti-TNFs (HR = 1.82) [175].

Gastrointestinal ulcer disease

Although increased in RA, there is currently no evidence to indicate that gastrointestinal ulcers are due to a specific RA process, but there is evidence that they are due to commonly used therapies in RA. Many studies have reportedly demonstrated the association of NSAIDs with gastrointestinal ulceration and the reduction in ulceration rates with COX-2 and gastrointestinal prophylactic agents [176–182]. The risk for gastrointestinal ulceration is also associated with corticosteroid use and increased further by concomitant NSAID usage in the UK General Practice Research Database [183]. Other risk factors for gastrointestinal ulceration, based on clinical trial and observational data in RA, include impaired functional status, older age, and previous ulceration.

Other: anemia, osteoporosis, and depression

Using the World Health Organization definition of anemia (hemoglobin <12 g/dl for women and <13 g/dl for men), anemia occurs in 31.5% of RA patients. After erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein is the strongest predictor of anemia, followed by estimated creatinine clearance. Severe chronic anemia (hemoglobin <10 g/dl) is rare in RA (3.4%). Overall, the rate of anemia is threefold higher in RA patients than in the general population [184].

Osteopenia is a consequence of RA, decreased physical activity, and treatment with corticosteroids [185–188]. In 394 female RA patients included in the Oslo County Rheumatoid Arthritis Register, a twofold increase in osteoporosis was reported compared with the general population [185]. Fractures resulting from osteoporosis rank highly among comorbidities contributing to mortality, future hospitalizations, and increased disability. The rate of fracture is increased twofold among persons with RA. Following 30,262 RA patients in the General Practice Research Database, van Staa and coworkers [186] found a RR for hip fracture of 2.0 (95% CI = 1.8 to 2.3) and spine fracture of 2.4 (95% CI = 2.0 to 2.8) compared with non-RA control individuals. Osteoporosis is increased in RA independent of corticosteroid usage [186–188]. Van Staa and coworkers [186] found the RR for an osteoporotic fracture in RA patients with no recent corticosteroid usage to be 1.2 (95% CI = 1.1 to 2.3), although this risk was more than doubled with recent corticosteroid use, even when used in low doses [185, 186, 189]. Despite the numerous reports and serious nature of osteoporosis, preventive care provided by rheumatologists is suboptimal [190] (assessing the need for additional protective therapies including bisphosphonates and parathyroid hormone, monitoring bone mass by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, and providing calcium and vitamin D supplementation).

Depression is concomitant with virtually all chronic illnesses and is not increased in RA compared with those with other chronic illnesses [191]. Evidence suggests that depression leads to increased mortality in persons with RA [192].

Outcome after comorbidity in rheumatoid arthritis

Not only do persons with RA appear to be at increased risk for a number of important comorbidities, but outcome after comorbidities has also been shown to be poorer in persons with RA compared with the general population. Mortality after MI has been shown to be significantly higher in MI cases with RA than in MI cases who do not have RA (HR for mortality in RA versus non-RA: 1.46, 95% CI = 1.01 to 2.10; adjusted for age, sex, and calendar year) [118]. Likewise, 6-month mortality after heart failure was significantly worse in heart failure cases with RA versus those without (Figure 10) [118]. The risk for mortality at 30 days after heart failure was 2.57-fold higher for RA patients than for non-RA individuals after adjusting for age, sex, and calendar year, whereas the risk of mortality at 6 months after heart failure was 1.94-fold higher for RA patients compared to non-RA individuals after similar adjustment. These comparisons were both highly statistically significant.

Twelve-month mortality after heart failure. Reproduced from [118] with permission.

There is strong evidence that persons with RA are at high risk for developing several comorbid disorders. Comorbid conditions in persons with RA may have atypical features and thus may be difficult to diagnose. There is no evidence that the excess risks for these comorbidities have declined. Emerging evidence points to poorer outcomes after comorbidity in persons with RA compared with the general population.

Conclusion

The past decade has brought many new insights regarding the epidemiology and comorbidity of the rheumatic diseases. It has been demonstrated that the incidence and prevalence of these conditions is dynamic, not static, and appears to be influenced by both genetic and environmental factors. There is strong evidence that persons with RA are at high risk for developing several comorbid disorders. Comorbid conditions in persons with RA may have atypical features and thus may be difficult to diagnose. There is no evidence that the excess risks of these comorbidities have declined. Emerging evidence points to poorer outcomes after comorbidity in persons with RA compared with the general population.

Taken together these findings underscore the complexity of the rheumatic diseases and highlight the key role of epidemiological research in understanding these intriguing conditions.

Note

The Scientific Basis of Rheumatology: A Decade of Progress

This article is part of a special collection of reviews, The Scientific Basis of Rheumatology: A Decade of Progress, published to mark Arthritis Research & Therapy's 10th anniversary.

Other articles in this series can be found at: http://arthritis-research.com/sbr

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- COX:

-

cyclo-oxygenase

- GCA:

-

giant cell arteritis

- HLA:

-

human leukocyte antigen

- HR:

-

hazard ratio

- ILD:

-

interstitial lung disease

- JRA:

-

juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

- MI:

-

myocardial infarction

- NSAID:

-

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- OA:

-

osteoarthritis

- PMR:

-

polymyalgia rheumatica

- PsA:

-

psoriatic arthritis

- RA:

-

rheumatoid arthritis

- RR:

-

relative risk

- SIR:

-

standardized incidence rate

- SLE:

-

systemic lupus erythematosus

- TB:

-

tuberculosis.

References

Oliver JE, Silman AJ: What epidemiology has told us about risk factors and aetiopathogenesis in rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2009, 11: 223-10.1186/ar2575.

Pedersen JK, Svendsen AJ, Horslev-Petersen K: Incidence of rheumatoid arthritis in the southern part of Denmark from 1995 to 2001. Open Rheumatol J. 2007, 1: 18-23.

Kaipiainen-Seppanen O, Kautiainen H: Declining trend in the incidence of rheumatoid factor-positive rheumatoid arthritis in Finland 1980–2000. J Rheumatol. 2006, 33: 2132-2138.

Garcia Rodriguez LA, Tolosa LB, Ruigomez A, Johansson S, Wallander MA: Rheumatoid arthritis in UK primary care: incidence and prior morbidity. Scand J Rheumatol. 2008

Pedersen JK, Kjaer NK, Svendsen AJ, Horslev-Petersen K: Incidence of rheumatoid arthritis from 1995 to 2001: impact of ascertainment from multiple sources. Rheumatol Int. 2009, 29: 411-415. 10.1007/s00296-008-0713-6.

Costenbader KH, Chang SC, Laden F, Puett R, Karlson EW: Geographic variation in rheumatoid arthritis incidence among women in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2008, 168: 1664-1670. 10.1001/archinte.168.15.1664.

Maradit Kremers H, Gabriel S: Epidemiology of the rheumatic diseases. Kelley's Textbook of Rheumatology. Edited by: Harris ED Jr. 2005, Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders, 407-425. 7

Alamanos Y, Voulgari PV, Drosos AA: Incidence and prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis, based on the 1987 American College of Rheumatology criteria: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 36: 182-188. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.08.006.

Doran MF, Pond GR, Crowson CS, O'Fallon WM, Gabriel SE: Trends in incidence and mortality in rheumatoid arthritis in Rochester, Minnesota, over a forty-year period. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 46: 625-631. 10.1002/art.509.

Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, Maradit Kremers H, Therneau TM: The rising incidence of rheumatoid arthritis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 58: S453-10.1002/art.23280.

Boyer GS, Benevolenskaya LI, Templin DW, Erdesz S, Bowler A, Alexeeva LI, Goring WP, Krylov MY, Mylov NM: Prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in circumpolar native populations. J Rheumatol. 1998, 25: 23-29.

Cimmino MA: Prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in Italy: the Chiavari study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998, 57: 315-318. 10.1136/ard.57.5.315.

Jacobsson LTH, Hanson RL, Knowler WC, Pillemer S, Pettitt DJ, McCance DR, Bennett PH: Decreasing incidence and prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in Pima Indians over a twenty-five-year period. Arthritis Rheum. 1994, 37: 1158-1165. 10.1002/art.1780370808.

Saraux A, Guedes C, Allain J, Devauchelle V, Valls I, Lamour A, Guillemin F, Youinou P, Le Goff P: Prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthropathy in Brittany, France. Societe de Rhumatologie de l'Ouest. J Rheumatol. 1999, 26: 2622-2627.

Simonsson M, Bergman S, Jacobsson LT, Petersson IF, Svensson B: The prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in Sweden. Scand J Rheumatol. 1999, 28: 340-343. 10.1080/03009749950155319.

Carbonell J, Cobo T, Balsa A, Descalzo MA, Carmona L: The incidence of rheumatoid arthritis in Spain: results from a nationwide primary care registry. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008, 47: 1088-1092. 10.1093/rheumatology/ken205.

Riise T, Jacobsen BK, Gran JT: Incidence and prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in the county of Troms, northern Norway. J Rheumatol. 2000, 27: 1386-1389.

Symmons D, Turner G, Webb R, Asten P, Barrett E, Lunt M, Scott D, Silman A: The prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in the United Kingdom: new estimates for a new century. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2002, 41: 793-800. 10.1093/rheumatology/41.7.793.

Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, O'Fallon WM: Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: have we made an impact in 4 decades?. J Rheumatol. 1999, 26: 2529-2533.

Kvalvik AG, Jones MA, Symmons DP: Mortality in a cohort of Norwegian patients with rheumatoid arthritis followed from 1977 to 1992. Scand J Rheumatol. 2000, 29: 29-37. 10.1080/030097400750001770.

Krause D, Schleusser B, Herborn G, Rau R: Response to methotrexate treatment is associated with reduced mortality in patients with severe rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000, 43: 14-21. 10.1002/1529-0131(200001)43:1<14::AID-ANR3>3.0.CO;2-7.

Riise T, Jacobsen BK, Gran JT, Haga HJ, Arnesen E: Total mortality is increased in rheumatoid arthritis. A 17-year prospective study. Clin Rheumatol. 2001, 20: 123-127. 10.1007/PL00011191.

Young A, Koduri G, Batley M, Kulinskaya E, Gough A, Norton S, Dixey J: Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Increased in the early course of disease, in ischaemic heart disease and in pulmonary fibrosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007, 46: 350-357. 10.1093/rheumatology/kel253.

Sacks JJ, Helmick CG, Langmaid G: Deaths from arthritis and other rheumatic conditions, United States, 1979–1998. J Rheumatol. 2004, 31: 1823-1828.

Gonzalez A, Maradit Kremers H, Crowson CS, Nicola PJ, Davis JM, Therneau TM, Roger VL, Gabriel SE: The widening mortality gap between rheumatoid arthritis patients and the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56: 3583-3587. 10.1002/art.22979.

Ward MM: Recent improvements in survival in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: better outcomes or different study designs?. Arthritis Rheum. 2001, 44: 1467-1469. 10.1002/1529-0131(200106)44:6<1467::AID-ART243>3.0.CO;2-6.

Ziadé N, Jougla E, Coste J: Population-level influence of rheumatoid arthritis on mortality and recent trends: a multiple cause-of-death analysis in France, 1970–2002. J Rheumatol. 2008, 35: 1950-1957.

Jacobsson LT, Turesson C, Nilsson JA, Petersson IF, Lindqvist E, Saxne T, Geborek P: Treatment with TNF blockers and mortality risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007, 66: 670-675. 10.1136/ard.2006.062497.

Choi HK, Hernán MA, Seeger JD, Robins JM, Wolfe F: Methotrexate and mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective study. Lancet. 2002, 359: 1173-1177. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08213-2.

Goodson NJ, Wiles NJ, Lunt M, Barrett EM, Silman AJ, Symmons DPM: Mortality in early inflammatory polyarthritis: cardiovascular mortality is increased in seropositive patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 46: 2010-2019. 10.1002/art.10419.

Soderlin MK, Nieminen P, Hakala M: Functional status predicts mortality in a community based rheumatoid arthritis population. J Rheumatol. 1998, 25: 1895-1899.

Wallberg-Jonsson S, Johansson H, Ohman ML, Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S: Extent of inflammation predicts cardiovascular disease and overall mortality in seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. A retrospective cohort study from disease onset. J Rheumatol. 1999, 26: 2562-2571.

Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, Maradit Kremers H, Doran MF, Turesson C, O'Fallon WM, Matteson E: Survival in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based analysis of trends over 40 years. Arthritis Rheum. 2003, 48: 54-58. 10.1002/art.10705.

Oen KG, Cheang M: Epidemiology of chronic arthritis in childhood. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1996, 26: 575-591. 10.1016/S0049-0172(96)80009-6.

von Koskull S, Truckenbrodt H, Holle R, Hormann A: Incidence and prevalence of juvenile arthritis in an urban population of southern Germany: a prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001, 60: 940-945. 10.1136/ard.60.10.940.

Kaipiainen-Seppanen O, Savolainen A: Changes in the incidence of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis in Finland. Rheumatology. 2001, 40: 928-932. 10.1093/rheumatology/40.8.928.

Andersson-Gäre B: Juvenile arthritis – who gets it, where and when? A review of current data on incidence and prevalence. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1999, 17: 367-374.

Prahalad S, Ryan MH, Shear ES, Thompson SD, Giannini EH, Glass DN: Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: linkage to HLA demonstrated by allele sharing in affected sibpairs. Arthritis Rheum. 2000, 43: 2335-2338. 10.1002/1529-0131(200010)43:10<2335::AID-ANR22>3.0.CO;2-W.

Forre O, Smerdel A: Genetic epidemiology of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2002, 31: 123-128. 10.1080/713798345.

Oen K, Fast M, Postl B: Epidemiology of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis in Manitoba, Canada, 1975–92: cycles in incidence. J Rheumatol. 1995, 22: 745-750.

Gare BA, Fasth A: Epidemiology of juvenile chronic arthritis in southwestern Sweden: a 5-year prospective study. Pediatrics. 1992, 90: 950-958.

Peterson LS, Mason T, Nelson AM, O'Fallon WM, Gabriel SE: Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis in Rochester, Minnesota 1960–1993. Arthritis Rheum. 1996, 39: 1385-1390. 10.1002/art.1780390817.

Peterson LS, Mason T, Nelson AM, O'Fallon WM, Gabriel SE: Psychosocial outcomes and health status of adults who have had juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: a controlled, population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 1997, 40: 2235-2240. 10.1002/art.1780401219.

Ruperto N, Levinson J, Ravelli A, Shear E, Link Tague B, Murray K, Martini A, Giannini E: Long-term health outcomes and quality of life in American and Italian inception cohorts of patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. I. Outcome status. J Rheumatol. 1997, 24: 945-951.

Zak M, Pedersen FK: Juvenile chronic arthritis into adulthood: a long-term follow-up study. Rheumatology. 2000, 39: 198-204. 10.1093/rheumatology/39.2.198.

French AR, Mason T, Nelson AM, O'Fallon WM, Gabriel SE: Increased mortality in adults with a history of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2001, 44: 523-527. 10.1002/1529-0131(200103)44:3<523::AID-ANR99>3.0.CO;2-1.

Minden K, Niewerth M, Listing J, Biedermann T, Bollow M, Schöntube M, Zink A: Long-term outcome in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 46: 2392-2401. 10.1002/art.10444.

Soderlin MK, Borjesson O, Kautiainen H, Skogh T, Leirisalo-Repo M: Annual incidence of inflammatory joint diseases in a population based study in southern Sweden. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002, 61: 911-915. 10.1136/ard.61.10.911.

Shbeeb M, Uramoto KM, Gibson LE, O'Fallon WM, Gabriel SE: The epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, USA, 1982–1991. J Rheumatol. 2000, 27: 1247-1250.

Harrison BJ, Silman AJ, Barrett EM, Scott DG, Symmons DP: Presence of psoriasis does not influence the presentation or short-term outcome of patients with early inflammatory polyarthritis. J Rheumatol. 1997, 24: 1744-1749.

Kaipiainen-Seppanen O, Aho K: Incidence of chronic inflammatory joint diseases in Finland in 1995. J Rheumatol. 2000, 27: 94-100.

Gladman DD, Farewell VT, Wong K, Husted J: Mortality studies in psoriatic arthritis: results from a single outpatient center. II. Prognostic indicators for death. Arthritis Rheum. 1998, 41: 1103-1110. 10.1002/1529-0131(199806)41:6<1103::AID-ART18>3.0.CO;2-N.

Wong K, Gladman DD, Husted J, Long JA, Farewell VT: Mortality studies in psoriatic arthritis: results from a single outpatient clinic. I. Causes and risk of death. Arthritis Rheum. 1997, 40: 1868-1872. 10.1002/art.1780401021.

Husted JA, Gladman DD, Farewell VT, Cook RJ: Health-related quality of life of patients with psoriatic arthritis: a comparison with patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001, 45: 151-158. 10.1002/1529-0131(200104)45:2<151::AID-ANR168>3.0.CO;2-T.

Wilson FC, Icen M, Crowson CS, McEvoy MT, Gabriel SE, Maradit Kremers H: Time trends in epidemiology and characteristics of psoriatic arthritis over 3 decades: a population-based study. J Rheumatol. 2009, 36: 361-367.

Oliveria SA, Felson DT, Reed JI, Cirillo PA, Walker AM: Incidence of symptomatic hand, hip, and knee osteoarthritis among patients in a health maintenance organization. Arthritis Rheum. 1995, 38: 1134-1141. 10.1002/art.1780380817.

Murphy L, Schwartz TA, Helmick CG, Renner JB, Tudor G, Koch G, Dragomir A, Kalsbeek WD, Luta G, Jordan JM: Lifetime risk of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 59: 1207-1213. 10.1002/art.24021.

Felson DT, Zhang Y: An update on the epidemiology of knee and hip osteoarthritis with a view to prevention. Arthritis Rheum. 1998, 41: 1343-1355. 10.1002/1529-0131(199808)41:8<1343::AID-ART3>3.0.CO;2-9.

Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, Arnold LM, Choi H, Deyo RA, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Hochberg MC, Hunder GG, Jordan JM, Katz JN, Kremers HM, Wolfe F, National Arthritis Data Work-group: Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 58: 26-35. 10.1002/art.23176.

Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, Campion ME, O'Fallon WM: Direct medical costs unique to people with arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1997, 24: 719-725.

Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, Campion ME, O'Fallon WM: Indirect and nonmedical costs among people with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis compared with nonarthritic controls. J Rheumatol. 1997, 24: 43-48.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality National and regional statistics in the national inpatient sample. [http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb34.jsp]

Yelin E: The economics of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis. Edited by: Brandt K, Doherty M, Lohmander LS. 1998, New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 23-30.

Uramoto KM, Michet CJJ, Thumboo J, Sunku J, O'Fallon WM, Gabriel SE: Trends in the incidence and mortality of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) – 1950–1992. Arthritis Rheum. 1999, 42: 46-50. 10.1002/1529-0131(199901)42:1<46::AID-ANR6>3.0.CO;2-2.

Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, Deyo RA, Felson DT, Giannini EH, Heyse SP, Hirsch R, Hochberg MC, Hunder GG, Liang MH, Pillemer SR, Steen VD, Wolfe F: Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 1998, 41: 778-799. 10.1002/1529-0131(199805)41:5<778::AID-ART4>3.0.CO;2-V.

Hochberg MC, Perlmutter DL, Medsger TA, Steen V, Weisman MH, White B, Wigley FM: Prevalence of self-reported physician-diagnosed systemic lupus erythematosus in the USA. Lupus. 1995, 4: 454-456. 10.1177/096120339500400606.

Ward MM, Pyun E, Studenski S: Long-term survival in systemic lupus erythematosus. Patient characteristics associated with poorer outcomes. Arthritis Rheum. 1995, 38: 274-283. 10.1002/art.1780380218.

Walsh SJ, DeChello LM: Geographical variation in mortality from systemic lupus erythematosus in the United States. Lupus. 2001, 10: 637-646. 10.1191/096120301682430230.

Wang F, Wang CL, Tan CT, Manivasagar M: Systemic lupus erythematosus in Malaysia: a study of 539 patients and comparison of prevalence and disease expression in different racial and gender groups. Lupus. 1997, 6: 248-253. 10.1177/096120339700600306.

Xie SK, Feng SF, Fu H: Long term follow-up of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Dermatol. 1998, 25: 367-373.

Salvarani C, Cantini F, Boiardi L, Hunder GG: Polymyalgia rheumatica and giant-cell arteritis. N Engl J Med. 2002, 347: 261-271. 10.1056/NEJMra011913.

Baldursson O, Steinsson K, Bjornsson J, Lie JT: Giant cell arteritis in Iceland. An epidemiologic and histopathologic analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 1994, 37: 1007-1012. 10.1002/art.1780370705.

Salvarani C, Gabriel SE, O'Fallon WM, Hunder GG: The incidence of giant cell arteritis in Olmsted County, Minnesota: apparent fluctuations in a cyclic pattern. Ann Intern Med. 1995, 123: 192-194.

Doran MF, Crowson CS, O'Fallon WM, Hunder GG, Gabriel SE: Trends in the incidence of polymyalgia rheumatica over a 30 year period in Olmsted County, Minnesota, USA. J Rheumatol. 2002, 29: 1694-1697.

Gonzalez-Gay MA, Garcia-Porrua C, Vazquez-Caruncho M, Dababneh A, Hajeer A, Ollier WE: The spectrum of polymyalgia rheumatica in northwestern Spain: incidence and analysis of variables associated with relapse in a 10 year study. J Rheumatol. 1999, 26: 1326-1332.

Nordborg E, Bengtsson B: Epidemiology of biopsy-proven giant cell arteritis (GCA). J Intern Med Res. 1990, 227: 233-236.

Machado EBV, Michet CJ, Ballard DJ, Hunder GG, Beard CM, Chu CP, O'Fallon WM: Trends in incidence and clinical presentation of temporal arteritis in Olmsted County, Minnesota: 1950–1985. Arthritis Rheum. 1988, 31: 745-749. 10.1002/art.1780310607.

Hall AP, Barry PE, Dawber TR, McNamara PM: Epidemiology of gout and hyperuricemia. A long-term population study. Am J Med. 1967, 42: 27-37. 10.1016/0002-9343(67)90004-6.

Currie WJ: Prevalence and incidence of the diagnosis of gout in Great Britain. Ann Rheum Dis. 1979, 38: 101-106. 10.1136/ard.38.2.101.

Harris CM, Lloyd DCEF, Lewis J: The prevalence and prophylaxis of gout in England. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995, 48: 1153-1158. 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00244-K.

Isomaki H, von Essen R, Ruutsalo HM: Gout, particularly diuretics-induced, is on the increase in Finland. Scand J Rheumatol. 1977, 6: 213-216. 10.3109/03009747709095452.

Klemp P, Stansfield SA, Castle B, Robertson MC: Gout is on the increase in New Zealand. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997, 56: 22-26. 10.1136/ard.56.1.22.

Lin KC, Lin HY, Chou P: Community based epidemiological study on hyperuricemia and gout in Kin-Hu, Kinmen. J Rheumatol. 2000, 27: 1045-1050.

Chang HY, Pan WH, Yeh WT, Tsai KS: Hyperuricemia and gout in Taiwan: results from the Nutritional and Health Survey in Taiwan (1993–96). J Rheumatol. 2001, 28: 1640-1646.

Roubenoff R, Klag MJ, Mead LA, Liang KY, Seidler AJ, Hochberg MC: Incidence and risk factors for gout in white men. JAMA. 1991, 266: 3004-3007. 10.1001/jama.266.21.3004.

Annemans L, Spaepen E, Gaskin M, Bonnemaire M, Malier V, Gilbert T, Nuki G: Gout in the UK and Germany: prevalence, comorbidities and management in general practice 2000–2005. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008, 67: 960-966. 10.1136/ard.2007.076232.

Mikuls TR, Farrar JT, Bilker WB, Fernandes S, Schumacher HR, Saag KG: Gout epidemiology: results from the UK General Practice Research Database, 1990–1999. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005, 64: 267-272. 10.1136/ard.2004.024091.

Pillemer SR, Matteson EL, Jacobsson LT, Martens PB, Melton LJ, O'Fallon WM, Fox PC: Incidence of physician-diagnosed primary Sjogren syndrome in residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001, 76: 593-599. 10.4065/76.6.593.

Haugen AJ, Peen E, Hulten B, Johannessen AC, Brun JG, Halse AK, Haga HJ: Estimation of the prevalence of primary Sjogren's syndrome in two age-different community-based populations using two sets of classification criteria: the Hordaland Health Study. Scand J Rheumatol. 2008, 37: 30-34. 10.1080/03009740701678712.

Bjerrum KB: Keratoconjunctivitis sicca and primary Sjogren's syndrome in a Danish population aged 30–60 years. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1997, 75: 281-286.

Zhang NZ, Shi CS, Yao QP, Pan GX, Wang LL, Wen ZX, Li XC, Dong Y: Prevalence of primary Sjogren's syndrome in China. J Rheumatol. 1995, 22: 659-661.

Alamanos Y, Tsifetaki N, Voulgari PV, Venetsanopoulou AI, Siozos C, Drosos AA: Epidemiology of primary Sjogren's syndrome in Northwest Greece, 1982–2003. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006, 45: 187-191. 10.1093/rheumatology/kei107.

Kabasakal Y, Kitapcioglu G, Turk T, Oder G, Durusoy R, Mete N, Egrilmez S, Akalin T: The prevalence of Sjogren's syndrome in adult women. Scand J Rheumatol. 2006, 35: 379-383. 10.1080/03009740600759704.

Tomsic M, Logar D, Grmek M, Perkovic T, Kveder T: Prevalence of Sjogren's syndrome in Slovenia. Rheumatology. 1999, 38: 164-170. 10.1093/rheumatology/38.2.164.

Carbone LD, Cooper C, Michet CJ, Atkinson EJ, O'Fallon WM, Melton LJD: Ankylosing spondylitis in Rochester, Minnesota, 1935–1989. Is the epidemiology changing?. Arthritis Rheum. 1992, 35: 1476-1482. 10.1002/art.1780351211.

Kaipiainen-Seppanen O, Aho K, Heliovaara M: Incidence and prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis in Finland. J Rheumatol. 1997, 24: 496-499.

Bakland G, Nossent HC, Gran JT: Incidence and prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis in Northern Norway. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 53: 850-855. 10.1002/art.21577.

Alamanos Y, Papadopoulos N, Voulgari P, Karakatsanis A, Siozos C, Drosos A: Epidemiology of ankylosing spondylitis in Northwest Greece, 1983–2002. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2002, 43: 615-618. 10.1093/rheumatology/keh133.

Hukuda S, Minami M, Saito T, Mitsui H, Matsui N, Komatsubara Y, Makino H, Shibata T, Shingu M, Sakou T, Shichikawa K: Spondyloarthropathies in Japan: nationwide questionnaire survey performed by the Japan Ankylosing Spondylitis Society. J Rheumatol. 2001, 28: 554-559.

De Angelis R, Salaffi F, Grassi W: Prevalence of spondyloarthropathies in an Italian population sample: a regional community-based study. Scand J Rheumatol. 2007, 36: 14-21. 10.1080/03009740600904243.

Saraux A, Guillemin F, Guggenbuhl P, Roux CH, Fardellone P, Le Bihan E, Cantagrel A, Chary-Valckenaere I, Euller-Ziegler L, Flipo RM, Juvin R, Behier JM, Fautrel B, Masson C, Coste J: Prevalence of spondyloarthropathies in France. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005, 64: 1431-1435. 10.1136/ard.2004.029207.

Lawrence RC, Everett DF, Benevolenskaya LI, Boyer GS, Erdesz S, Templin DW, Alexeeva LI, Lanier AP, Krylov MYu, Cornoni-Huntley JC, Mylov NM, Heyse S: Spondyloarthropathies in circumpolar populations: I. Design and methods of United States and Russian studies. Arctic Med Res. 1996, 55: 187-194.

Benevolenskaya LI, Boyer GS, Erdesz S, Templin DW, Alexeeva LI, Lawrence RC, Heyse SP, Krylov MY, Mylov NM, Cornoni-Huntley JC, Everett DF, Goring WP, Bowler A: Spondylarthropathic diseases in indigenous circumpolar populations of Russia and Alaska. Rev Rhum Engl Ed. 1996, 63: 815-822.

Wolfe F, Michaud K: The risk of myocardial infarction and pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic myocardial infarction predictors in rheumatoid arthritis: A cohort and nested case-control analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 58: 2612-2621. 10.1002/art.23811.

Michaud K, Wolfe F: Comorbidities in rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007, 21: 885-906. 10.1016/j.berh.2007.06.002.

Crowson CS, Nicola PJ, Maradit Kremers H, O'Fallon WM, Therneau TM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Ballman KV, Gabriel SE: How much of the increased incidence of heart failure in rheumatoid arthritis is attributable to traditional cardiovascular risk factors and ischemic heart disease?. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52: 3039-3044. 10.1002/art.21349.

Maradit-Kremers H, Nicola PJ, Crowson CS, Ballman KV, Gabriel SE: Cardiovascular death in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52: 722-732. 10.1002/art.20878.

Maradit-Kremers H, Crowson CS, Nicola PJ, Ballman KV, Roger VL, Jacobsen SJ, Gabriel SE: Increased unrecognized coronary heart disease and sudden deaths in rheumatoid arthritis: A population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52: 402-411. 10.1002/art.20853.

Watson D, Rhodes T, Guess H: All-cause mortality and vascular events among patients with RA, OA, or no arthritis in the UK General Practice Research Database. J Rheumatol. 2003, 30: 1196-1202.

Wolfe F, Freundlich B, Straus WL: Increase in cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease prevalence in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2003, 30: 36-40.

Solomon DH, Karlson EW, Rimm EB, Cannuscio CC, Mandl LA, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC: Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in women diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation. 2003, 107: 1303-1307. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000054612.26458.B2.

Fischer LM, Schlienger RG, Matter C, Jick H, Meier CR: Effect of rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus on the risk of first-time acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2004, 93: 198-200. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.09.037.

Sodergren A, Stegmayr B, Lundberg V, Ohman ML, Wallberg-Jonsson S: Increased incidence of and impaired prognosis after acute myocardial infarction among patients with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007, 66: 263-266. 10.1136/ard.2006.052456.

Turesson C, Jarenros A, Jacobsson L: Increased incidence of cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from a community based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004, 63: 952-955. 10.1136/ard.2003.018101.

del Rincon ID: High incidence of cardiovascular events in a rheumatoid arthritis cohort not explained by traditional cardiac risk factors. Arthritis Rheum. 2001, 44: 2737-2745. 10.1002/1529-0131(200112)44:12<2737::AID-ART460>3.0.CO;2-#.

Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB: Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998, 97: 1837-1847.

Nicola PJ, Maradit-Kremers H, Roger VL, Jacobsen SJ, Crowson CS, Ballman KV, Gabriel SE: The risk of congestive heart failure in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study over 46 years. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52: 412-420. 10.1002/art.20855.

Davis JM, Roger VL, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, Therneau TM, Gabriel SE: The presentation and outcome of heart failure in patients with rheumatoid arthritis differs from that in the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 58: 2603-2611. 10.1002/art.23798.

Corrao S, Salli L, Arnone S, Scaglione R, Pinto A, Licata G: Echo-Doppler left ventricular filling abnormalities in patients with rheumatoid arthritis without clinically evident cardiovascular disease. Eur J Clinical Invest. 1996, 26: 293-297. 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1996.133284.x.

Di Franco M, Paradiso M, Mammarella A, Paoletti V, Labbadia G, Coppotelli L, Taccari E, Musca A: Diastolic function abnormalities in rheumatoid arthritis. Evaluation By echo Doppler transmitral flow and pulmonary venous flow: relation with duration of disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000, 59: 227-229. 10.1136/ard.59.3.227.

Mustonen J, Laakso M, Hirvonen T, Mutru O, Pirnes M, Vainio P, Kuikka JT, Rautio P, Lansimies E: Abnormalities in left ventricular diastolic function in male patients with rheumatoid arthritis without clinically evident cardiovascular disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 1993, 23: 246-253. 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1993.tb00769.x.

Smitten AL, Simon TA, Hochberg MC, Suissa S: A meta-analysis of the incidence of malignancy in adult patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008, 10: R45-10.1186/ar2404.

Baecklund E, Iliadou A, Askling J, Ekbom A, Backlin C, Granath F, Catrina AI, Rosenquist R, Feltelius N, Sundström C, Klareskog L: Association of chronic inflammation, not its treatment, with increased lymphoma risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54: 692-701. 10.1002/art.21675.

Karlson EW, Lee IM, Cook NR, Manson JE, Buring JE, Hennekens CH: A retrospective cohort study of cigarette smoking and risk of rheumatoid arthritis in female health professionals. Arthritis Rheum. 1999, 42: 910-917. 10.1002/1529-0131(199905)42:5<910::AID-ANR9>3.0.CO;2-D.

Criswell LA, Merlino LA, Cerhan JR, Mikuls TR, Mudano AS, Burma M, Folsom AR, Saag KG: Cigarette smoking and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis among postmenopausal women: results from the Iowa Women's Health Study. Am J Med. 2002, 112: 465-471. 10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01051-3.

Sugiyama D, Nishimura K, Tamaki K, Tsuji G, Nakazawa T, Morinobu A, Kumagai S: Impact of smoking as a risk factor for developing rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009

James WH: Hypothesis: gonadal hormones act as confounders in epidemiological studies of the associations between some behavioural risk factors and some pathological conditions. J Theor Biol. 2001, 209: 97-102. 10.1006/jtbi.2000.2249.

Chakravarty EF, Michaud K, Wolfe F: Skin cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. J Rheumatol. 2005, 32: 2130-2135.

Wolfe F, Michaud K: Biologic treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of malignancy: analyses from a large US observational study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56: 2886-2895. 10.1002/art.22864.

Dawson JK, Fewins HE, Desmond J, Lynch MP, Graham DR: Fibrosing alveolitis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis as assessed by high resolution computed tomography, chest radiography, and pulmonary function tests. Thorax. 2001, 56: 622-627. 10.1136/thorax.56.8.622.

Wolfe F, Caplan L, Michaud K: Rheumatoid arthritis treatment and the risk of severe interstitial lung disease. Scand J Rheumatol. 2007, 36: 172-178. 10.1080/03009740601153774.