Abstract

The objective of this study was to analyse levels of the proinflammatory cytokine macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) in patients with primary Sjögren's syndrome (pSS) and to examine associations of MIF with clinical, serological and immunological variables. MIF was determined by ELISA in the sera of 76 patients with pSS. Further relevant cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, IL-10, IFN-γ and TNF-α) secreted by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were determined by ELISPOT assay. Lymphocytes and monocytes were examined flow-cytometrically for the expression of activation markers. Results were correlated with clinical and laboratory findings as well as with the HLA-DR genotype. Healthy age- and sex-matched volunteers served as controls. We found that MIF was increased in patients with pSS compared with healthy controls (p < 0.01). In particular, increased levels of MIF were associated with hypergammaglobulinemia. Further, we found a negative correlation of MIF levels with the number of IL-10-secreting PBMC in pSS patients (r = -0.389, p < 0.01). Our data indicate that MIF might participate in the pathogenesis of primary Sjögren's syndrome. MIF may contribute to B-cell hyperactivity indicated by hypergammaglobulinemia. The inverse relationship of IL-10 and MIF suggests that IL-10 works as an antagonist of MIF in pSS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sjögren's syndrome is an autoimmune disorder characterized by keratoconjunctivitis sicca and xerostomia. Apart from the effects on the lachrymal and salivary glands, various extraglandular manifestations may develop. In addition, an increased risk of lymphoproliferative diseases, especially non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, has been widely described [1]. Focal lymphocytic gland infiltration with upregulated T helper type 1 cytokine expression as well as B-lymphocyte hyperactivity leading to the production of circulating autoantibodies and hypergammaglobulinemia are hallmark characteristics of the disease.

Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) was discovered in 1966 and initially characterized as a T-cell-derived cytokine that inhibits the migration of macrophages in vitro [2, 3]. After cloning of MIF in 1989, a much broader range of biological functions has emerged [4]. MIF seems to be a broad-spectrum proinflammatory cytokine with a pivotal role in the regulation of innate and adaptive immune responses [5]. There is increasing evidence for a role of MIF as a proinflammatory cytokine in autoimmune diseases [6]. Serum levels of MIF have been shown to be correlated with the disease activity in several autoimmune disorders including juvenile idiopathic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and Wegener's granulomatosis [7–9]. Foote and colleagues [10] recently reported increased MIF levels and a correlation with the disease activity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.

Recent findings suggest that MIF might participate in the pathogenesis of other diseases of connective tissue. The present study was designed to elucidate the role of MIF in primary Sjögren's syndrome (pSS).

We examined serum levels of MIF in patients with pSS and the relation of these levels to clinical and laboratory findings. In addition, we analysed associations of MIF concentrations with various cytokines that have been implicated in the pathogenesis of pSS [11, 12] as well as with different activation markers on peripheral blood lymphocytes and monocytes.

Moreover, to elucidate whether the production of MIF is influenced by immunogenetic factors we analysed the potential association of MIF levels with distinct HLA-DR genotypes.

Materials and methods

Patients and healthy controls

Seventy-six patients with pSS were included in this study. The diagnosis of pSS was based on the American–European Consensus criteria [13]. Patient characteristics and laboratory findings are given in Table 1. None of the participating patients with pSS were on glucocorticoids, but some patients received hydroxychloroquine (n = 12) or azathioprine (n = 5) as a disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug. Twenty-eight age- and sex-matched volunteers served as healthy controls.

For analysis of HLA-DR association, 152 healthy sex-matched German Caucasians were used as controls. The study protocol was approved by the local independent ethics committee. Patients and controls gave informed consent to participate in this study.

Detection of MIF

MIF was detected by enzyme-linked immunoassay as reported previously [14]. In brief, 96-well plates (Nunc GmbH, Wiesbaden, Germany) were coated with mouse anti-human MIF monoclonal antibody (R&D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany). Non-specific binding sites were blocked by the addition of 250 μl of phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% bovine serum albumin/5% sucrose/0.05% NaN3 and incubation for 16 h at 4°C. After plates had been washed three times, recombinant human MIF standards (R&D Systems) and test sera were added to the wells and incubated for 2 h. Biotinylated polyclonal goat anti-human MIF (R&D Systems) was used as the detection antibody and streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase (Jackson/Dianova GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) as the second-step reagent. Colour was developed with 3,3' 5' 5-tetramethylbenzidine (Sigma-Aldrich, Munich, Germany) and absorbance was measured at 450 nm against standard curves. All analyses were performed in duplicate, and mean values were reported. The detection limit of the MIF assay was 0.015 ng/ml.

ELISPOT analysis and flow cytometry

On samples from 48 consecutive patients with pSS from our cohort, we performed an ELISPOT assay as well as flow cytometric determination of activated lymphocytes and macrophages.

Previously described methods were used for the isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and cell cultures and for the ELISPOT analysis [15].

We analysed the secretion of IL-1, IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α by unstimulated PBMC. For the detection of IFN-γ, cells were stimulated with 20 μg/ml T-cell mitogen phytohemagglutinin (Endogen, Boston, MA, USA). Spots were automatically counted with an electronic computer-assisted imaging system (Autoimmun Diagnostika GmbH, Strassberg, Germany), which has been shown to be valid and precise [16].

Flow cytometric determination of lymphocyte and monocyte subpopulations was performed by two-colour immunofluorescence analysis on a Coulter XL cytometer (Beckman-Coulter, Krefeld, Germany) as described previously [17]. Activated CD4+ T cells (CD4/CD25, CD4/CD45RO, CD4/CD69, CD4/CD71), activated CD19+ B cells (CD19/CD86) and activated CD14+ monocytes (CD14/HLA-DR) were detected by fluorescein isothiocyanate-labelled and phycoerythrin-labelled monoclonal antibodies (Beckman-Coulter). Results were expressed as the percentage of positive cells.

Other laboratory parameters

Routine laboratory parameters (namely erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein (CRP), full blood count, total protein and serum electrophoresis) were determined simultaneously. Rheumatoid factor isotypes were analysed by the ELISA technique. We also performed the Waaler–Rose hemagglutination test and the latex fixation test for rheumatoid factor (Dade Behring, Schwalbach, Germany). The levels of IgG antibodies against Ro and La were determined by the ELISA technique (Pharmacia Upjohn, Freiburg, Germany). Serum concentrations of complement levels (C3c and C4) were measured by nephelometry (BN2; Dade-Behring). Low complement levels were defined as C3c levels below 80 mg/dl or C4 levels below 10 mg/dl. Protein electrophoresis was performed with Olympus Hite 320 equipment (Olympus-Diagnostika, Hamburg, Germany). Hypergammaglobulinemia was diagnosed if γ-globulin levels were above 19% in the protein electrophoresis.

HLA-DR typing

Generic HLA-DR typing was performed by using an enzyme-linked probe hybridization assay (ELPHA; Biotest, Dreieich, Germany). Sequence-specific oligonucleotide probes were used to determine polymorphic sequence motifs. Hybridization between probe and target DNA was detected by a method adapted from the protein ELISA technique.

Statistics

Data were analysed with the statistical software package SPSS 12.0. Nonparametric tests were used for statistical analysis because a normal distribution of values could not be assumed. The Mann–Whitney U test was employed for unpaired samples. The Spearman correlation test was used to correlate laboratory results and clinical data. χ2 and Fisher's exact tests were applied to analyse qualitative variables. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Serum MIF levels in patients with pSS and healthy controls

Serum levels of MIF were significantly increased in patients with pSS (median 29.8 ng/ml; range 5.7 to 148 ng/ml) compared with healthy controls (5.7 ng/ml; range 0.015 to 35.3 ng/ml; p < 0.01). No significant differences of MIF levels were found between patients with pSS receiving therapy with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs and those not receiving it, nor did we observe any differences of MIF levels between patients taking hydroxychloroquine or azathioprine. There was no association of MIF with disease duration or age of patients.

Association of MIF levels with laboratory and clinical features

Patients with hypergammaglobulinemia (n = 57) had significantly increased levels of MIF compared with healthy controls (p < 0.01) and compared with patients with pSS with normal γ-globulins (p < 0.05; Figure 1). Correspondingly, the percentage of γ-globulins also correlated with MIF serum levels (r = 0.278, p < 0.05).

There were no associations of MIF levels with anti-Ro or anti-La antibody titers, rheumatoid factor isotypes or other laboratory findings listed in Table 1. None of the patients with pSS had an increased level of CRP.

There was a tendency for increased numbers of IL-10-secreting PBMC in patients with pSS (p < 0.066, data not shown). Numbers of PBMC secreting IL-1, IL-6, IFN-γ or TNF-α did not differ significantly from those in healthy controls (data not shown).

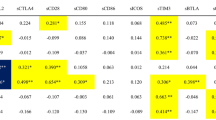

We found a negative correlation of MIF levels with the number of IL-10-secreting PBMC (r = 0.389, p < 0.01). Patients with low MIF levels had a significantly increased number of IL-10-secreting PBMC compared with patients with high MIF levels and compared with healthy controls (p < 0.01; Figure 2). In contrast, there were no significant associations of MIF with numbers of PBMC secreting IL-1, IL-6, IFN-γ or TNF-α.

IL-10-secreting peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) in patients with primary Sjögren's syndrome and healthy controls (HC). Data of Sjögren's syndrome patients were divided into a low-MIF group (0 to 33%), an intermediate-MIF group (more than 33 to 66%) and a high-MIF group (more than 66%). The number of IL-10-secreting PBMC in the low-MIF group was significantly increased compared with the high-MIF group or healthy controls.

The percentage of CD4/CD71+ T cells was significantly increased in patients with pSS compared with healthy controls (p < 0.05, data not shown) but there were no significant correlations of MIF levels with the expression of different activation markers on CD4+ T cells (CD4/CD25, CD4/CD45RO, CD4/CD69, CD4/CD71), CD19+ B cells (CD19/CD86) or CD14+ monocytes (CD14/HLA-DR). No significant correlations in the absolute numbers of these cell populations were observed.

We found no associations of MIF levels with different glandular or extraglandular manifestations listed in Table 1. In the three patients with a previous B-cell lymphoma the MIF level was significantly increased compared with that in healthy controls (p < 0.01) but did not differ significantly from that of other patients with pSS without lymphoma.

HLA-DR associations

The prevalence of HLA-DR3 was increased in patients with pSS compared with healthy controls (34.3% versus 12.5%; p < 0.01, data not shown). There was no association of MIF levels with different HLA-DR genotypes.

Discussion

Our data show significantly increased serum levels of MIF in patients with pSS, especially in those with increased γ-globulins. Hypergammaglobulinemia has been linked with the extent of histopathological salivary gland abnormalities and has been proposed as an activation marker in pSS [18, 19]. An increased production of γ-globulins results from polyclonal B-cell hyperactivity [20]. MIF can provide signals for B cells to proliferate [21]. It has been shown that neutralization of MIF significantly inhibits antibody production in vivo [22]. Increased production of MIF might therefore contribute to hypergammaglobulinemia and possibly reflects disease activity of pSS.

MIF has been associated with various autoimmune diseases [7–10]. The induction and regulation of MIF in autoimmune diseases is not well characterized [23]. It has been shown that low concentrations of glucocorticoids induce MIF production from macrophages; this could be part of a counter-regulatory system that functions to control immune responses [24]. Previous results showing increased levels of MIF in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus could partly be explained by corticosteroid use [10]. However, because our patients with pSS did not receive any glucocorticoids, the increased MIF levels could not be explained by this argument.

MIF has been shown to be increased in acute inflammation and a correlation with CRP concentrations has been described [8, 25]. As the acute-phase reactant CRP was not elevated in our cohort, the increased MIF levels in patients with pSS cannot be explained by differences in the extent of acute-phase response. Hence, specific mechanisms of MIF induction in pSS remain to be elucidated.

There was an increased prevalence of HLA-DR3 in our cohort of patients with pSS, confirming previous findings [26]. Antibodies against Ro and La have been shown to be associated with HLA-DR3, possibly as a result of HLA haplotype-dependent differences in presentation of autoantigens and subsequent stimulation of the immune response [26]. We detected no associations of MIF levels with the HLA-DR genotype, suggesting that HLA-DR polymorphism does not have a major role in the generation of MIF.

We found a negative correlation of MIF with IL-10-secreting PBMC. In addition, we observed a tendency towards an increased number of IL-10-secreting PBMC in our cohort, as reported previously [27]. It has been shown in vitro that IL-10 inhibits MIF synthesis [28]. Moreover, neutralization of MIF leads to an increase of IL-10 production in an animal model [29]. IL-10 has been described as a potent macrophage deactivator that inhibits cytokine production by activated macrophages [30]. Our data might indicate downregulation of MIF by IL-10 in vivo and suggest that IL-10 and MIF are part of a negative regulatory circuit. It might be assumed that IL-10 counteracts MIF-induced inflammatory processes such as activation of macrophages, as reported previously [28].

We found no association of MIF with other cytokine-secreting PBMC in our patients. It has been shown that MIF can upregulate proinflammatory cytokines including TNF-α in vitro [31]. However, other authors have not identified any TNF-inducing effect of MIF on PBMC [32]. Recently it has been shown that MIF alone is not sufficient to induce cytokine expression: co-stimulators such as lipopolysaccaride are necessary to induce the secretion of TNF-α and IL-1 [33]. This suggests that MIF may act to modulate and amplify the response to lipopolysaccharide in sepsis. In pSS, MIF apparently has no inducing effect on TNF-α or other proinflammatory cytokines analysed, presumably because of a lack of such co-stimulatory factors.

The percentage of CD4/CD71+ T cells was significantly increased in patients with pSS compared with healthy controls, as reported previously [34]. We did not find an association of MIF with various activation markers on T helper cells, B cells or macrophages, although MIF has been identified as an activator of B and T cells as well as macrophages [4, 21, 22]. Recently it has been suggested that MIF is a critical effector of organ injury in systemic lupus erythematosus in the absence of major changes in T-cell and B-cell markers or alterations in autoantibody production [35]. Most probably this observation holds also true for pSS.

MIF has no homology with any other proinflammatory cytokine, and the mechanisms by which MIF exerts its biological effects are not yet fully understood [33]. It is possible that MIF mediates organ injury directly, because it has been shown that MIF induces the production of matrix metalloproteinase-9 [36], which has been implicated in the pathogenesis of pSS [37]. MIF can stimulate the inducible nitric oxide synthase and increase the production of nitric oxide, which can directly mediate cell injury [38]. It has been suggested that nitric oxide contributes to inflammatory damage and acinar cell atrophy in Sjögren's syndrome [39].

Our three patients with B-cell lymphoma had increased MIF levels compared with healthy controls, but there were no significant differences from patients with pSS without B-cell lymphoma.

Patients with pSS are at increased risk of developing B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma [1]. It has been suggested that MIF provides a link between inflammation and tumorigenesis [21, 40].

MIF expression is increased in sporadic human colorectal adenomas [41]. MIF has been shown to decrease the tumor suppressor activity of p53 and to upregulate Bcl-2 expression [42], which has been suggested to be important in B-cell monoclonal proliferation and malignant transformation in pSS [43]. A deficiency of p53 tumor suppressor activity is associated with the development of low-grade mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma [44]. It has been shown in a lymphoma mouse model that loss of MIF markedly delays the onset of B-cell lymphoma development in vivo [45].

Conclusion

This study provides the first in vivo evidence for a potential role of MIF in pSS. Additional investigation is required to substantiate the association of MIF with disease activity and the development of lymphomas. Eventually, targeting of MIF may offer therapeutic options in this autoimmune disease.

Abbreviations

- CRP:

-

= C-reactive protein

- ELISA:

-

= enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- IL:

-

= interleukin

- IFN:

-

= interferon

- MIF:

-

= macrophage migration inhibitory factor

- PBMC:

-

= peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- pSS:

-

= primary Sjögren's syndrome

- TNF:

-

= tumor necrosis factor.

References

Kassan SS, Thomas TL, Moutsopoulos HM, Hoover R, Kimberly RP, Budman DR, Costa J, Decker JL, Chused TM: Increased risk of lymphoma in sicca syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1978, 89: 888-892.

David JR: Delayed hypersensitivity in vitro: its mediation by cell-free substances formed by lymphoid cell–antigen interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1966, 56: 72-77. 10.1073/pnas.56.1.72.

Bloom BR, Bennett B: Mechanism of a reaction in vitro associated with delayed-type hypersensitivity. Science. 1966, 153: 80-82. 10.1126/science.153.3731.80.

Weiser WY, Pozzi LM, Titus RG, David JR: Recombinant human migration inhibitory factor has adjuvant activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992, 89: 8049-8052. 10.1073/pnas.89.17.8049.

Larson DF, Horak K: Macrophage migration inhibitory factor: controller of systemic inflammation. Crit Care. 2006, 10: 138-10.1186/cc4899.

Bucala R, Lolis E: Macrophage migration inhibitory factor: a critical component of autoimmune inflammatory diseases. Drug News Perspect. 2005, 18: 417-426. 10.1358/dnp.2005.18.7.939345.

Donn R, Alourfi Z, De Benedetti F, Meazza C, Zeggini E, Lunt M, Stevens A, Shelley E, Lamb R, Ollier WE, et al: Mutation screening of the macrophage migration inhibitory factor gene: positive association of a functional polymorphism of macrophage migration inhibitory factor with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 46: 2402-2409. 10.1002/art.10492.

Morand EF, Leech M, Weedon H, Metz C, Bucala R, Smith MD: Macrophage migration inhibitory factor in rheumatoid arthritis: clinical correlations. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2002, 41: 558-562. 10.1093/rheumatology/41.5.558.

Becker H, Maaser C, Mickholz E, Dyong A, Domschke W, Gaubitz M: Relationship between serum levels of macrophage migration inhibitory factor and the activity of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitides. Clin Rheumatol. 2006, 25: 368-372. 10.1007/s10067-005-0045-9.

Foote A, Briganti EM, Kipen Y, Santos L, Leech M, Morand EF: Macrophage migration inhibitory factor in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2004, 31: 268-273.

Azuma M, Motegi K, Aota K, Hayashi Y, Sato M: Role of cytokines in the destruction of acinar structure in Sjogren's syndrome salivary glands. Lab Invest. 1997, 77: 269-280.

Ohyama Y, Nakamura S, Matsuzaki G, Shinohara M, Hiroki A, Fujimura T, Yamada A, Itoh K, Nomoto K: Cytokine messenger RNA expression in the labial salivary glands of patients with Sjogren's syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1996, 39: 1376-1384. 10.1002/art.1780390816.

Vitali C, Bombardieri S, Jonsson R, Moutsopoulos HM, Alexander EL, Carsons SE, Daniels TE, Fox PC, Fox RI, Kassan SS, et al: Classification criteria for Sjogren's syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002, 61: 554-558. 10.1136/ard.61.6.554.

Maaser C, Eckmann L, Paesold G, Kim HS, Kagnoff MF: Ubiquitous production of macrophage migration inhibitory factor by human gastric and intestinal epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2002, 122: 667-680. 10.1053/gast.2002.31891.

Willeke P, Schotte H, Erren M, Schlüter B, Mickholz E, Domschke W, Gaubitz M: Concomitant reduction of disease activity and IL-10 secreting peripheral blood mononuclear cells during immunoadsorption in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2002, 48: 323-329.

Vaquerano JE, Peng M, Chang JW, Zhou YM, Leong SP: Digital quantification of the enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT). Biotechniques. 1998, 25: 830-834, 836.

Willeke P, Schluter B, Schotte H, Erren M, Mickholz E, Domschke W, Gaubitz M: Increased frequency of GM-CSF secreting PBMC in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus can be reduced by immunoadsorption. Lupus. 2004, 13: 257-262. 10.1191/0961203304lu1009oa.

Vitali C, Tavoni A, Simi U, Marchetti G, Vigorito P, d'Ascanio A, Neri R, Cristofani R, Bombardieri S: Parotid sialography and minor salivary gland biopsy in the diagnosis of Sjogren's syndrome. A comparative study of 84 patients. J Rheumatol. 1988, 15: 262-267.

Pillemer SR, Smith J, Fox PC, Bowman SJ: Outcome measures for Sjogren's syndrome, April 10–11, Bethesda, Maryland, USA. J Rheumatol. 2005, 32: 143-149.

Gottenberg JE, Busson M, Cohen-Solal J, Lavie F, Abbed K, Kimberly RP, Sibilia J, Mariette X: Correlation of serum B lymphocyte stimulator and β2 microglobulin with autoantibody secretion and systemic involvement in primary Sjogren's syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005, 64: 1050-1055. 10.1136/ard.2004.030643.

Chesney J, Metz C, Bacher M, Peng T, Meinhardt A, Bucala R: An essential role for macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) in angiogenesis and the growth of a murine lymphoma. Mol Med. 1999, 5: 181-191.

Bacher M, Metz CN, Calandra T, Mayer K, Chesney J, Lohoff M, Gemsa D, Donnelly T, Bucala R: An essential regulatory role for macrophage migration inhibitory factor in T-cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996, 93: 7849-7854. 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7849.

Popa C, van Lieshout AW, Roelofs MF, Geurts-Moespot A, van Riel PL, Calandra T, Sweep FC, Radstake TR: MIF production by dendritic cells is differentially regulated by Toll-like receptors and increased during rheumatoid arthritis. Cytokine. 2006, 36: 51-56. 10.1016/j.cyto.2006.10.011.

Calandra T, Bernhagen J, Metz CN, Spiegel LA, Bacher M, Donnelly T, Cerami A, Bucala R: MIF as a glucocorticoid-induced modulator of cytokine production. Nature. 1995, 377: 68-71. 10.1038/377068a0.

de Mendonca-Filho HT, Gomes GS, Nogueira PM, Fernandes MA, Tura BR, Santos M, Castro-Faria-Neto HC: Macrophage migration inhibitory factor is associated with positive cultures in patients with sepsis after cardiac surgery. Shock. 2005, 24: 313-317. 10.1097/01.shk.0000180622.52058.3a.

Gottenberg JE, Busson M, Loiseau P, Cohen-Solal J, Lepage V, Charron D, Sibilia J, Mariette X: In primary Sjogren's syndrome, HLA class II is associated exclusively with autoantibody production and spreading of the autoimmune response. Arthritis Rheum. 2003, 48: 2240-2245. 10.1002/art.11103.

Halse A, Tengner P, Wahren-Herlenius M, Haga H, Jonsson R: Increased frequency of cells secreting interleukin-6 and interleukin-10 in peripheral blood of patients with primary Sjogren's syndrome. Scand J Immunol. 1999, 49: 533-538. 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1999.00533.x.

Wu J, Cunha FQ, Liew FY, Weiser WY: IL-10 inhibits the synthesis of migration inhibitory factor and migration inhibitory factor-mediated macrophage activation. J Immunol. 1993, 151: 4325-4332.

Cvetkovic I, Al-Abed Y, Miljkovic D, Maksimovic-Ivanic D, Roth J, Bacher M, Lan HY, Nicoletti F, Stosic-Grujicic S: Critical role of macrophage migration inhibitory factor activity in experimental autoimmune diabetes. Endocrinology. 2005, 146: 2942-2951. 10.1210/en.2004-1393.

Bogdan C, Vodovotz Y, Nathan C: Macrophage deactivation by interleukin 10. J Exp Med. 1991, 174: 1549-1555. 10.1084/jem.174.6.1549.

Calandra T, Bernhagen J, Mitchell RA, Bucala R: The macrophage is an important and previously unrecognized source of macrophage migration inhibitory factor. J Exp Med. 1994, 179: 1895-1902. 10.1084/jem.179.6.1895.

de Jong YP, Abadia-Molina AC, Satoskar AR, Clarke K, Rietdijk ST, Faubion WA, Mizoguchi E, Metz CN, Alsahli M, ten Hove T, et al: Development of chronic colitis is dependent on the cytokine MIF. Nat Immunol. 2001, 2: 1061-1066. 10.1038/ni720.

Kudrin A, Scott M, Martin S, Chung CW, Donn R, McMaster A, Ellison S, Ray D, Ray K, Binks M: Human macrophage migration inhibitory factor: a proven immunomodulatory cytokine?. J Biol Chem. 2006, 281: 29641-29651. 10.1074/jbc.M601103200.

Willeke P, Gaubitz M, Schotte H, Becker H, Mickholz E, Domschke W, Schluter B: Clinical and immunological characteristics of patients with Sjogren's syndrome in relation to α-fodrin antibodies. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007, 46: 479-483. 10.1093/rheumatology/kel270.

Hoi AY, Hickey MJ, Hall P, Yamana J, O'Sullivan KM, Santos LL, James WG, Kitching AR, Morand EF: Macrophage migration inhibitory factor deficiency attenuates macrophage recruitment, glomerulonephritis, and lethality in MRL/lpr mice. J Immunol. 2006, 177: 5687-5696.

Kong YZ, Yu X, Tang JJ, Ouyang X, Huang XR, Fingerle-Rowson G, Bacher M, Scher LA, Bucala R, Lan HY: Macrophage migration inhibitory factor induces MMP-9 expression: implications for destabilization of human atherosclerotic plaques. Atherosclerosis. 2005, 178: 207-215. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.08.030.

Azuma M, Aota K, Tamatani T, Motegi K, Yamashita T, Harada K, Hayashi Y, Sato M: Suppression of tumor necrosis factor α-induced matrix metalloproteinase 9 production by the introduction of a super-repressor form of inhibitor of nuclear factor κBα complementary DNA into immortalized human salivary gland acinar cells. Prevention of the destruction of the acinar structure in Sjogren's syndrome salivary glands. Arthritis Rheum. 2000, 43: 1756-1767. 10.1002/1529-0131(200008)43:8<1756::AID-ANR12>3.0.CO;2-H.

Liew FY: Regulation of nitric oxide synthesis in infectious and autoimmune diseases. Immunol Lett. 1994, 43: 95-98. 10.1016/0165-2478(94)00157-X.

Konttinen YT, Platts LA, Tuominen S, Eklund KK, Santavirta N, Tornwall J, Sorsa T, Hukkanen M, Polak JM: Role of nitric oxide in Sjogren's syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1997, 40: 875-883. 10.1002/art.1780400515.

Hudson JD, Shoaibi MA, Maestro R, Carnero A, Hannon GJ, Beach DH: A proinflammatory cytokine inhibits p53 tumor suppressor activity. J Exp Med. 1999, 190: 1375-1382. 10.1084/jem.190.10.1375.

Wilson JM, Coletta PL, Cuthbert RJ, Scott N, MacLennan K, Hawcroft G, Leng L, Lubetsky JB, Jin KK, Lolis E, et al: Macrophage migration inhibitory factor promotes intestinal tumorigenesis. Gastroenterology. 2005, 129: 1485-1503. 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.07.061.

Beswick EJ, Pinchuk IV, Suarez G, Sierra JC, Reyes VE: Helicobacter pylori CagA-dependent macrophage migration inhibitory factor produced by gastric epithelial cells binds to CD74 and stimulates procarcinogenic events. J Immunol. 2006, 176: 6794-6801.

Masaki Y, Sugai S: Lymphoproliferative disorders in Sjogren's syndrome. Autoimmun Rev. 2004, 3: 175-182. 10.1016/S1568-9972(03)00102-2.

Du M, Peng H, Singh N, Isaacson PG, Pan L: The accumulation of p53 abnormalities is associated with progression of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Blood. 1995, 86: 4587-4593.

Talos F, Mena P, Fingerle-Rowson G, Moll U, Petrenko O: MIF loss impairs Myc-induced lymphomagenesis. Cell Death Differ. 2005, 12: 1319-1328. 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401653.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Eva Mickholz for technical assistance. CM is supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; MA 2247/2-1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

PW participated in the data analysis and the design of the study, and drafted the manuscript. MG, HS and HB helped with data collection, patient recruitment and the design of the study. MG, HS, WD, CM and HB helped in editing the manuscript. CM provided technical help for the MIF analysis. BS participated in the design and helped in the statistical analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Willeke, P., Gaubitz, M., Schotte, H. et al. Increased serum levels of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in patients with primary Sjögren's syndrome . Arthritis Res Ther 9, R43 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2182

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2182