Abstract

Interleukin-17 (IL-17) is a T cell cytokine spontaneously produced by cultures of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) synovial membranes. High levels have been detected in the synovial fluid of patients with RA. The trigger for IL-17 is not fully identified; however, IL-23 promotes the production of IL-17 and a strong correlation between IL-15 and IL-17 levels in synovial fluid has been observed. IL-17 is a potent inducer of various cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-1, and receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL). Additive or even synergistic effects with IL-1 and TNF-α in inducing cytokine expression and joint damage have been shown in vitro and in vivo. This review describes the role of IL-17 in the pathogenesis of destructive arthritis with a major focus on studies in vivo in arthritis models. From these studies in vivo it can be concluded that IL-17 becomes significant when T cells are a major element of the arthritis process. Moreover, IL-17 has the capacity to induce joint destruction in an IL-1-independent manner and can bypass TNF-dependent arthritis. Anti-IL-17 cytokine therapy is of interest as an additional new anti-rheumatic strategy for RA, in particular in situations in which elevated IL-17 might attenuate the response to anti-TNF/anti-IL-1 therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Interleukin-17 and family members

Interleukin-17 (IL-17) is a 17 kDa protein that is secreted as a dimer by a restricted set of cells, predominantly activated human memory T cells or mouse αβTCR+CD4-CD8- thymocytes [1–3]. Rouvier and colleagues have cloned cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-8 (rat IL-17) from a T cell subtraction library [4] and mouse IL-17 was cloned from a thymus-derived, activated T cell cDNA library [3]. Subsequently, the human counterpart of mouse IL-17 was cloned by two independent groups [1, 2, 5]. Human IL-17 has 25% amino acid sequence homology to mouse IL-17, as well as 72% homology to an open-reading frame from the T lymphotropic herpes virus saimiri (HVS13) and 63% homology to CTLA8 [2, 4]. In addition to IL-17 (IL-17A) another five members of the IL-17 family have been discovered (IL-17B-F) by large-scale sequencing of the human and other vertebrate genomes (Table 1) [6].

The different IL-17 family members seem to have very distinct expression patterns, suggesting distinct biological roles. IL-17B is moderately expressed in several peripheral tissues as well as immune tissues [7, 8], and IL-17E is expressed in various peripheral tissues [9]. Interestingly, IL-17F has biological functions similar to those of IL-17(A) and is also produced by activated monocytes [10, 11]. This indicates that the IL-17 family might contribute to the pathology of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and other inflammatory diseases not only through activated T cells but also through activated monocytes/macrophages. Further work will be required to determine the precise mechanism of action of IL-17 and its family members such as IL-17F, IL-17B, and IL-17E in the development of chronic synovitis and tissue destruction during arthritis, especially in relation to other known key cytokines (IL-1, tumor necrosis factor [TNF], and receptor activator of NF-κB ligand [RANKL]).

IL-17 signaling

In contrast to the restricted expression of IL-17, the IL-17 receptor (IL-17R) is ubiquitously expressed in virtually all cells and tissues. It is a type I transmembrane protein that has no sequence similarity to any other known cytokine receptor [5]. The exact mechanisms of IL-17 signaling are not fully elucidated. Binding of IL-17 to its unique receptor results in activation of the adapter molecule TNF-receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), which is required for IL-17 signaling [12]. IL-17 shares transcriptional pathways with IL-1 and TNF. It can activate NF-κB and all three classes of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases including extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK)1 and ERK2, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38 [13–15]. These pathways have been identified in synoviocytes [16] and chondrocytes [14]. Four other receptors for the IL-17 family have been identified so far: IL-17RH1 [8] and IL-17RL (receptor-like) [17], IL-17RD, and IL-17RE, which share partial sequence homology to IL-17R [18] (Table 1). The expression pattern of these new receptors seems to be more cell/tissue-specific than that of the IL-17R, and the ligand specificities of many of these receptors have not been established.

Regulation of IL-17

The physiological stimulus for the induction of IL-17 expression has not been fully identified. Microbial stimuli induced the expression of IL-17 together with TNF-α in both murine and human T cells [19]. Cell–cell contact of human T cells with fibroblasts resulted in increased mRNA expression of IL-17 and IL-17R. Supernatants obtained from cell–cell contact-stimulated peripheral blood lymphocytes enhance the production of IL-6 and IL-8 by fibroblast-like synoviocytes, an effect that was blocked by antibodies against IL-17 [20]. Furthermore, IL-15 produced by synoviocytes is considered to be a potent inducer of IL-17 production [21, 22]. Moreover, IL-23 produced by activated DCs and macrophages acts on memory T cells, promoting the production of IL-17 (both IL-17 and IL-17F) [23]. In addition, a direct role was suggested for IL-23 in IL-17 production by CD8+ T cells [23, 24]. IL-23 affects memory T cell and inflammatory macrophage function, and IL-23 (but not IL-12) is a critical factor in autoimmune inflammation to the central nervous system [25].

Further support for IL-23 as an important trigger for IL-17 was obtained from studies with IL-23-specific knockout mice [26, 27]. Specific absence of IL-23 completely prevented collagen-induced arthritis (CIA), whereas loss of IL-12 exacerbates CIA [26]. Interestingly, resistance was correlated with an absence of IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells despite normal induction of collagen-specific, interferon-γ-producing T helper 1 cells. In contrast, IL-12-deficient p35-deficient mice developed more IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells, as well as an elevated expression of proinflammatory cytokines (such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-17) in affected tissues of diseased mice [26]. Importantly, IL-23-deficient mice resemble IL-17-deficient mice phenotypically [27, 28]. These studies indicate the existence of an IL-23/IL-17 axis of communication between the innate and adaptive parts of the immune system that might be an interesting target for the immunotherapy of inflammatory autoimmune diseases [26, 27].

Role of IL-17 in the pathogenesis of RA

RA is a chronic systemic disorder that is characterized by autoimmunity, infiltration of joint synovium by activated inflammatory cells, synovial hyperplasia, neoangiogenesis and progressive destruction of cartilage and bone. RA is considered to be a systemic Th1-associated inflammatory joint disease, and T cells comprise a large proportion of the inflammatory cells invading the synovial tissue. T cell activation and migration into the synovium occur as an early consequence of disease, and these cells adopt a pro-inflammatory phenotype. Considerable evidence now supports a role for T cells in the initiation and perpetuation of chronic inflammation prevalent in RA. Although T cells represent a large proportion of the inflammatory cells during inflammation, T cell-derived cytokines are much less abundant. However, because the vast majority of these are memory T cells, IL-17 is upregulated in early disease.

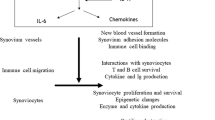

There is now considerable evidence from studies in vitro with RA synovium and/or co-cultures that IL-17 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine produced only by cells of the immune system, which is thought to contribute to inflammation associated with RA [29]. IL-17 is spontaneously produced by RA synovial membrane cultures, and IL-17-producing cells were found in T cell-rich areas [30] and high levels have been detected in the synovial fluid of patients with RA [21, 30, 31]. Although bioactive IL-17 is detected in RA and osteoarthritis synovial fluid, the levels of IL-17 were found to be higher in RA synovial fluid than in osteoarthritis synovial fluid [30, 31]. The expression of IL-17 in Th1 and Th2 cells seems to be different depending upon the conditions. Th1/Th0, but not Th2, subsets of CD4+ T cell clones isolated from rheumatoid synovium produced IL-17 [32]. In contrast, IL-17 production was found in both Th1 and Th2 clones from human skin-derived nickel-specific T cells [33]. In mice, IL-17 is produced by T cells expressing TNF-α but not by Th1 or Th2 cells [19]. IL-17 stimulates transcriptional NF-κB activity and IL-6 and IL-8 secretion in fibroblastic, endothelial, and epithelial cells, and induces T cell proliferation [1, 5]. Furthermore, it triggers human synoviocytes to produce granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor and prostaglandin E2 [1], suggesting that IL-17 could be an upstream mediator in the pathogenesis of arthritis and might have a function in fine-tuning the inflammatory response.

T cell IL-17 also stimulates the production of IL-1 and TNF-α from human PBMC-derived macrophages in vitro [34]. It enhances IL-1-mediated IL-6 production by RA synoviocytes in vitro as well as TNF-α-induced synthesis of IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8 [35, 36]. This indicates that IL-17 synergizes with IL-1 and TNF, and it has been shown that the combination of TNF-α blockade with IL-1 and IL-17 blockade is more effective for controlling IL-6 production in RA synovium cultures [37]. In addition, IL-17 induces RANKL expression, which is an essential cytokine for osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption [31]. IL-17 can synergize with these cytokines (IL-1, TNF, and RANKL), but probably acts directly as well. Furthermore, when IL-17 is combined with other cytokines that are already thought to be important in arthritic disease (such as TNF-α and IL-1), even more marked tissue destruction occurs [37] (Lubberts E, Koenders MI, Van den Berg WB, unpublished data). These observations strongly implicate IL-17 as having an important function in the disease pathogenesis of RA (Fig. 1).

Role of IL-17 in T cell immunity and/or propagation of joint inflammation

In arthritis, IL-17 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine thought to contribute to the joint inflammatory process [38]. Studies in IL-17-deficient mice revealed that IL-17 has an important function in the activation of T cells in allergen-specific T cell-mediated immune responses [28]. Furthermore, IL-17 has a function in the antigen-specific T cell activation phase of CIA [39]. Of interest, CIA was markedly but not completely suppressed in IL-17-deficient mice. IL-17 was responsible for the priming of collagen-specific T cells and for collagen-specific IgG2a production [39]. In contrast, the spontaneous development of destructive arthritis in mice deficient in IL-1 receptor antagonist could be completely prevented after inactivation of IL-17 [40]. In line with the situation in most RA patients, low systemic levels of IL-17 were found after the immunization protocol of CIA but IL-17 expression in the synovium gradually increased after the onset of CIA [41]. Early neutralization of endogenous IL-17 using the IL-17 receptor IgG1 Fc fusion protein starting after the immunization protocol during the initial phase of arthritis suppresses the onset of experimental arthritis [41]. Moreover, neutralizing endogenous IL-17 with anti-IL-17 sera after the onset of CIA still diminished the severity of CIA [42]. Histological analysis confirmed the suppression of joint inflammation, and systemic IL-6 levels were significantly decreased after treatment with anti-IL-17 antisera. In contrast, systemic as well as local IL-17 overexpression using an adenoviral vector expressing murine IL-17 accelerated the onset of CIA and aggravated synovial inflammation at the site [41, 43]. These observations strongly implicate a role for IL-17 at various levels in disease pathogenesis of arthritis. IL-17 seems to have a function in T cell immunity and in the propagation of joint inflammation.

Role of IL-17 in cartilage destruction

IL-17 has dual effects on cartilage. This T cell cytokine inhibits chondrocyte metabolism in intact articular cartilage of mice and induces proteoglycan breakdown (Table 2) [44–47]. Furthermore, studies in vitro showed the induction of metalloproteinases by IL-17 in synoviocytes and chondrocytes [48–50]. Interestingly, the IL-17 family subtypes IL-17F and IL-17E also showed cartilage destructive potential in vitro [11, 47] (Table 2). Another IL-17 family member, IL-17B, has been shown to be expressed by chondrocytes in normal bovine articular cartilage, mostly in the mid and deep zones [18].

IL-17 shares biological activities with IL-1, which is a key cytokine in the induction of cartilage destruction [51]. In vitro, IL-17 suppresses matrix synthesis by articular chondrocytes through enhancement of nitric oxide production [45, 52–54]. However, it has been shown that the effects of IL-17 on matrix degradation and synthesis were not dependent on IL-1 production by chondrocytes and IL-1Ra did not block IL-17-induced matrix release nor did they prevent the inhibition of matrix synthesis in vitro with pig articular cartilage explants [47]. In contrast, the IL-17-induced production of prostaglandin E2 and nitric oxide by cartilage explants is dependent on leukemia inhibitory factor [47, 54]. Interestingly, an IL-1-independent role of IL-17 in the pathogenesis of experimental arthritis was demonstrated [41]. The downstream signaling pathways for IL-17 and IL-1 seem to be distinct, and differential activation of activator protein 1 (AP-1) members by IL-17 and IL-1β has been described [49]. Although IL-1 is by far the more catabolic cytokine in experimental arthritis in comparison with TNF-α, the combination of IL-17 and TNF-α synergizes to induce cartilage destruction in vitro [55] as well as in vivo (Lubberts E, unpublished data). These data suggest that IL-17 alone or in combination with TNF-α might circumvent the catabolic effects of IL-1 on cartilage.

Interrelation between IL-17, polymorphonuclear cell influx, and cartilage destruction

In mice, local overexpression of IL-17 in the knee joint of both naive mice and mice immunized with type II collagen (CII) leads to enhanced influx of polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) [41]. A main difference between IL-17 over-expression in naive and CII-immunized DBA-1 mice was the observation that, in CIA, PMNs were heavily sticking to patella and femur cartilage, a phenomenon that was not observed in naive mice. Interestingly, under both conditions, local IL-17 induced proteoglycan depletion (Table 2). However, no chondrocyte death and cartilage erosion was observed in naive mice after local IL-17 gene transfer (Table 2). In contrast, local IL-17 aggravates cartilage erosion in CIA [41].

The lack of irreversible cartilage destruction under naive conditions in contrast to CIA conditions might be due to the lack of immune complexes formed during IL-17-induced joint inflammation in normal mice. Although IL-17 overexpression induced enhanced synovial stromelysin (pro-matrix metalloproteinase [pro-MMP]-3) expression under naive as well as CIA conditions (Lubberts E, unpublished data), the presence of immune complexes might be required for the cleavage process of pro-MMPs into active MMPs. This phenomenon is not well understood.

The elevated neutrophil influx and subsequent sticking to anti-CII immune complexes in the cartilage surface layer during CIA probably releases oxygen species and proteolytic enzymes present in PMNs directly into the surface of cartilage, thereby escaping inhibitors present in the synovial fluid [41, 56, 57]. IL-17 might enhance immune complex formation in CIA because IL-17 has a crucial function in activating autoantigen-specific cellular and humoral immune responses [39].

In contrast to aggravation of cartilage damage by IL-17 overexpression, neutralizing endogenous IL-17 in arthritis models protects against cartilage destruction. Both reversible proteoglycan depletion and the irreversible cartilage markers chondrocyte death and cartilage surface erosion were suppressed after neutralizing IL-17 after the onset of CIA [42]. A reduced influx of PMNs was noted and fewer IL-1β-positive cells were detected in the synovial infiltrate after treatment with anti-IL-17 antibody [42]. Furthermore, the induction of chronic relapsing streptococcal cell wall-induced arthritis in mice deficient in the IL-17 receptor (IL-17R) revealed the critical role for T cell IL-17/IL-17R signaling in driving synovial IL-1 expression and different metalloproteinases (Koenders MI, Kolls JK, Van den Berg WB, Lubberts E, unpublished data). These observations suggest that the presence of T cell IL-17 in the synovial infiltrate has major influences on PMN influx, synovial IL-1 expression, and the cartilage destructive process. IL-17 therefore seems to be a significant target for the treatment of cartilage destruction in T cell-mediated arthritis.

Role of IL-17 in bone erosion

In addition to the role of IL-17 in cartilage destruction, this T cell cytokine is a potent stimulator of osteoclastogenesis (Fig. 2). Promotion of type I collagen degradation in synovium and bone by IL-17 has been demonstrated, and when combined with IL-1, a marked synergistic release of collagen was noted [44]. IL-17 in combination with TNF-α increased osteoclastic resorption in vitro [58]. Furthermore, IL-17 induced the expression of RANKL in cultures of osteoblasts [31]. RANKL is a crucial regulator of osteoclastogenesis [59]. RANKL binds to its unique receptor activator of NF-κB (RANK) [60], and the RANKL/ RANK pathway seems of crucial importance in osteoclastogenesis and the bone erosion process. RANKL and the decoy receptor osteoprotegerin [61] are important positive and negative regulators of osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. Regulation of IL-17 and RANKL, as shown by IL-4 gene therapy in collagen arthritis, prevents osteoclastogenesis and bone erosion [62]. Systemic treatment with a soluble IL-17 receptor fusion protein (sIL-17R:Fc) starting before arthritis expression in experimental arthritis prevented bone erosion [41, 63]. Moreover, development of bone erosion in the chronic relapsing streptococcal cell wall-induced arthritis model in IL-17R-deficient mice was significantly suppressed (Lubberts E, Van den Berg WB, Kolls JK, unpublished data). In contrast, local IL-17 overexpression in the knee joint of CII-immunized mice resulted in promotion of collagen arthritis and aggravated joint destruction [43, 64]. In the CIA model it was shown that IL-17 promoted bone erosion through loss of the RANKL/osteoprotegerin balance [64]. Systemic treatment with osteoprotegerin prevented joint damage induced by local IL-17 gene transfer in CII-immunized mice. This strongly suggests that IL-17 is a potent inducer of RANKL and that the IL-17-induced promotion of bone erosion is strongly mediated by RANKL.

Interrelation between IL-17 and IL-1/TNF

Overexpression of IL-17 in the mouse knee joint of CII-immunized mice resulted in elevated levels of IL-1β protein in the synovium [41]. Intriguingly, blocking of IL-1α/β with neutralizing antibodies had no effect on the IL-17-induced synovial inflammation and joint damage, implying an IL-1-independent pathway [41]. This direct potency of IL-17 was underscored in the unabated IL-17-induced exaggeration of bacterial cell wall-induced arthritis in IL-1β-deficient mice [41]. Apart from IL-1, synergistic effects between IL-17 and TNF in systems in vitro have been reported regarding cytokine induction and cartilage damage [44, 55]. Because in mice IL-17-producing T cells also express TNF-α we performed blocking studies with IL-17 and TNF inhibitors. In line with the observations in vitro with RA synovial co-cultures [37], a combination blockade of TNF-α and IL-17 suppressed continuing CIA and was more effective than neutralizing TNF alone (Lubberts E, Van den Berg WB, unpublished data). It is of interest that TNF-α-dependent arthritis can be circumvented by IL-17 (Koenders MI, Lubberts E, Van den Berg WB, unpublished data). This underscores the potential of IL-17 to act additively or even synergistically with IL-1/TNF. Moreover, it also shows that T cell IL-17 can replace the proinflammatory/catabolic function of IL-1/ TNF, directly or through interplay with other macrophage-driven factors.

Role of IL-17 in other inflammatory/autoimmune diseases

Apart from the role of IL-17 in autoimmune arthritis, IL-17 and its family members exhibit a potential role in other inflammatory diseases, such as lung, gut, and skin inflammation [65–69]. IL-17 has a function in T-cell-triggered inflammation by stimulating stromal cells to secrete various cytokines and growth factors associated with inflammation [1, 2]. IL-17 regulates gene expression and protein synthesis of the complement system [70]. It has a regulatory role on C3 expression and synthesis and an amplifying effect on TNF-induced factor B synthesis [70]. In addition, IL-17 stimulates granulopoiesis and is a strong inducer of neutrophil recruitment through chemokine release [65, 71]. Furthermore, IL-17 promotes angiogenesis [72] and a role for IL-17 was suggested in allogeneic T cell proliferation that might be mediated in part through a maturation-inducing effect on dendritic cells (DC) [73]. Studies in IL-17-deficient mice revealed that this T cell cytokine had an important function in the activation of T cells in allergen-specific T cell-mediated immune responses [28]. IL-17 induced neutrophil accumulation in infected lungs. Greatly diminished recruitment of neutrophils into lungs was found in mice with homozygous deletion of the IL-17 receptor in response to a challenge with a Gram-negative pathogen [74]. Overproduction of IL-17 has been associated with several chronic disease conditions, suggesting a role of IL-17 in these diseases. IL-17E transgenic mice showed growth retardation, jaundice, a Th2-biased response, and multi-organ inflammation [75]. Furthermore, IL-17 expression was observed in ovarian, endometrial, and cervical cancers exhibiting angiogenic effects [76, 77]. Elevated levels of IL-17 were found in other autoimmune diseases, such as experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis [78], and in patients with systemic sclerosis [79]. However, further studies are needed to unravel the role of IL-17 in the pathogenesis of these autoimmune inflammations.

Conclusions

IL-17 is a T cell-derived cytokine produced by activated T cells, predominantly by activated CD4+CD45RO+ memory cells, and is expressed in the synovium of patients with RA. IL-17 has a function in T cell-triggered inflammation by stimulating different cell types to secrete various cytokines and chemokines. In addition, IL-17 shows additive or even synergistic effects with IL-1 and TNF in inducing cytokine expression and joint pathology. Furthermore, T cell IL-17 is a potent inducer of RANKL, a crucial cytokine in osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. IL-17 can act together with these cytokines but has direct pathological effects as well. It has been shown that IL-17 has IL-1-independent activities in inducing synovial inflammation and joint destruction in experimental arthritis. Furthermore, IL-17 has a function in prolongation of the arthritis process and can be considered an important target for the treatment of destructive arthritis.

The discovery of IL-17 family members may further extend the role of this cytokine family in arthritis pathology. IL-17F showed similar biological effects to those of IL-17; however, IL-17F is expressed in activated monocytes in addition to activated T cells. Further studies will be required to determine the contribution and precise mechanism of action of the novel IL-17 family member(s), with emphasis on the interaction with other known key cytokines in the pathogenesis of arthritis. Furthermore, IL-23 seems to be an important physiological stimulus for the induction of IL-17 and IL-17F, although other mediators might also be involved [21, 23, 26, 27].

Results so far suggest strongly that IL-17 is a novel target for the treatment of destructive arthritis. Because it is known that this T cell factor can have synergistic effects with catabolic/inflammatory mediators, it is tempting to speculate that IL-17 levels can influence whether or not a patient will respond to anti-TNF and anti-IL-1 therapy. Anti-IL-17 cytokine therapy might be an interesting new anti-rheumatic approach that could contribute to the prevention of joint destruction as an adjunct to anti-TNF and anti-IL-1 therapy.

Abbreviations

- CIA:

-

collagen-induced arthritis

- CII:

-

type II collagen

- IL:

-

interleukin

- MMP:

-

matrix metalloproteinase

- PMN:

-

polymorphonuclear cell

- RA:

-

rheumatoid arthritis

- RANKL:

-

receptor activator of NF-κB ligand

- TNF:

-

tumor necrosis factor.

References

Fossiez F, Djossou O, Chomarat P, Flores-Romo L, Ait-Yahia S, Maat C, Pin J-J, Garrone P, Garcia E, Saeland S, et al: T cell interleukin-17 induces stromal cells to produce proinflammatory and hematopoietic cytokines. J Exp Med. 1996, 183: 2593-2603. 10.1084/jem.183.6.2593.

Yao Z, Painter SL, Fanslow WC, Ulrich D, Macduff BM, Spriggs MK, Armitage RJ: Human IL-17: a novel cytokine derived from T cells. J Immunol. 1995, 155: 5483-5486.

Kennedy J, Rossi DL, Zurawski SM, Vega F, Kastelein RA, Wagner JL, Hannum CH, Zlotnik A: Mouse IL-17: a cytokine preferentially expressed by αβ TCR+CD4-CD8- T cells. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1996, 16: 611-617.

Rouvier E, Luciani M-F, Mattei M-G, Denizot F, Golstein P: CTLA-8, cloned from an activated T cell, bearing AU-rich messenger RNA instability sequences, and homologous to a Herpesvirus Saimiri gene. J Immunol. 1993, 150: 5445-5456.

Yao Z, Fanslow WC, Seldin MF, Rousseau A-M, Painter SL, Comeau MR, Cohen JI, Spriggs MK: Herpesvirus Saimiri encodes a new cytokine, IL-17, which binds to a novel cytokine receptor. Immunity. 1995, 3: 811-821. 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90070-5.

Aggarwal S, Gurney AL: IL-17: prototype member of an emerging cytokine family. J Leuk Biol. 2002, 71: 1-8.

Li H, Chen J, Huang A, Stinson J, Heldens S, Foster J, Dowd P, Gurney AL, Wood WI: Cloning and characterization of IL-17B and IL-17C, two new members of the IL-17 cytokine family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000, 97: 773-778. 10.1073/pnas.97.2.773.

Shi Y, Ullrich SJ, Zhang J, Connolly K, Grzegorzewski KJ, Barber MC, Wang W, Wathen K, Hodge V, Fisher CL, et al: A novel cytokine receptor-ligand pair. Identification, molecular characterization, and in vivo immunomodulatory activity. J Biol Chem. 2000, 275: 19167-19176. 10.1074/jbc.M910228199.

Lee J, Ho WH, Maruoka M, Corpuz RT, Baldwin DT, Foster JS, Goddard AD, Yansura DG, Vandlen RL, Wood WI, et al: IL-17E, a novel proinflammatory ligand for the IL-17 receptor homolog IL-17Rh1. J Biol Chem. 2001, 276: 1660-1664. 10.1074/jbc.M008289200.

Starnes T, Robertson MJ, Sledge G, Kelich S, Nakshatri H, Broxmeyer HE, Hromas R: Cutting edge: IL-17F, a novel cytokine selectively expressed in activated T cells and monocytes, regulates angiogenesis and endothelial cell cytokine production. J Immunol. 2001, 167: 4137-4140.

Hymowitz SG, Filvaroff EH, Yin JP, Lee J, Cai L, Risser P, Maruoka M, Mao W, Foster J, Kelley RF, et al: IL-17s adopt a cystine knot fold: structure and activity of a novel cytokine, IL-17F, and implications for receptor binding. EMBO J. 2001, 20: 5332-5341. 10.1093/emboj/20.19.5332.

Schwandner R, Yamaguchi K, Cao Z: Requirement of tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF)6 in interleukin-17 signal transduction. J Exp Med. 2000, 191: 1233-1240. 10.1084/jem.191.7.1233.

Awane M, Andres PG, Li DJ, Reinecker HC: NF-κB-inducing kinase is a common mediator of IL-17-, TNF-α, and IL-1β-induced chemokine promoter activation in intestinal epithelial cells. J Immunol. 1999, 162: 5337-5344.

Shalom-Barak T, Quach J, Lotz M: Interleukin-17-induced gene expression in articular chondrocytes is associated with activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases and NF-κB. J Biol Chem. 1998, 273: 27467-27473. 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27467.

Laan M, Lotvall J, Chung KF, Linden A: IL-17-induced cytokine release in human bronchial epithelial cells in vitro: role of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases. Br J Pharmacol. 2001, 133: 200-206. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704063.

Kehlen A, Thiele K, Riemann D, Langner J: Expression, modulation and signaling of IL-17 receptor in fibroblast-like synoviocytes of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002, 127: 539-546. 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01782.x.

Haudenschild D, Moseley T, Rose L, Reddi AH: Soluble and transmembrane isoforms of novel interleukin-17 receptor-like protein by RNA splicing and expression in prostate cancer. J Biol Chem. 2002, 277: 4309-4316. 10.1074/jbc.M109372200.

Moseley TA, Haudenschild DR, Rose L, Reddi AH: Interleukin-17 family and IL-17 receptors. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 2003, 14: 155-174. 10.1016/S1359-6101(03)00002-9.

Infante-Duarte C, Horton HF, Byrne MC, Kamradt T: Microbial lipopeptides induce the production of IL-17 in Th cells. J Immunol. 2000, 165: 6107-6115.

Thiele K, Riemann D, Navarrete Santos A, Langner J, Kehlen A: Cell-cell contact of human T cells with fibroblasts changes lymphocytic mRNA expression: increased mRNA expression of interleukin-17 and interleukin-17 receptor. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2000, 11: 53-58.

Ziolkowska M, Koc A, Luszczykiewics G, Ksiezopolska-Pietrzak K, Klimczak E, Chwalinska-Sadowska H, Maslinski W: High levels of IL-17 in rheumatoid arthritis patients: IL-15 triggers in vitro IL-17 production via cyclosporin A-sensitive mechanism. J Immunol. 2000, 164: 2832-2838.

Ferretti S, Bonneau O, Dubois GR, Jones CE, Trifilieff A: IL-17, produced by lymphocytes and neutrophils, is necessary for lipopolysaccharide-induced airway neutrophilia: IL-15 as a possible trigger. J Immunol. 2003, 170: 2106-2112.

Aggarwal S, Gilardi N, Xie MH, de Sauvage FJ, Gurney AL: Interleukin-23 promotes a distinct CD4 T cell activation state characterized by the production of interleukin-17. J Biol Chem. 2003, 17: 1910-1914. 10.1074/jbc.M207577200.

Happel KI, Zheng M, Young E, Quinton LJ, Lockhart E, Ramsay AJ, Shellito JE, Schurr JR, Bagby GJ, Nelson S, et al: Cutting edge: roles of Toll-like receptor 4 and IL-23 in IL-17 expression in response to Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. J Immunol. 2003, 170: 4432-4436.

Cua DJ, Sherlock J, Chen YI, Murphy CA, Joyce B, Seymour B, Luclan L, To W, Kwan S, Churakova T, et al: Interleukin-23 rather than interleukin-12 is the critical cytokine for autoimmune inflammation of the brain. Nature. 2003, 42: 744-748. 10.1038/nature01355.

Murphy C, Langrish CL, Chen Y, Blumenschein W, McClanahan T, Kastelein RA, Sedwick JD, Cua DJ: Divergent pro- and anti-inflammatory roles for IL-23 and IL-12 in joint autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med. 2003, 198: 1951-1957. 10.1084/jem.20030896.

Ghilardi N, Kljavin N, Chen Qi, Lucas S, Gurney AL, de Sauvage FJ: Compromised humoral and delayed-type hypersensitivity responses in IL-23-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2004, 172: 2827-2833.

Nakae S, Komiyama Y, Nambu A, Sudo K, Iwase M, Homma I, Sekikawa K, Asano M, Iwakura Y: Antigen-specific T cell sensitization is impaired in IL-17-deficient mice, causing suppression of allergic cellular and humoral responses. Immunity. 2002, 17: 375-387. 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00391-6.

Miossec P: Interleukin-17 in rheumatoid arthritis. If T cells were to contribute to inflammation and destruction through synergy. Arthritis Rheum. 2003, 48: 594-601. 10.1002/art.10816.

Chabaud M, Durand JM, Buchs N, Fossiez F, Page G, Frappart L, Miossec P: Human interleukin-17: a T cell-derived proinflammatory cytokine produced by the rheumatoid synovium. Arthritis Rheum. 1999, 42: 963-970. 10.1002/1529-0131(199905)42:5<963::AID-ANR15>3.0.CO;2-E.

Kotake S, Udagawa N, Takahashi N, Matsuzaki K, Itoh K, Ishiyama S, Saito S, Inoue K, Kamatani N, Gillespie MT, et al: IL-17 in synovial fluids from patients with rheumatoid arthritis is a potent stimulator of osteoclastogenesis. J Clin Invest. 1999, 103: 1345-1352.

Aarvak T, Chabaud M, Miossec P, Natvig JB: IL-17 is produced by some proinflammatory Th1/Th0 cells but not by Th2 cells. J Immunol. 1999, 162: 1246-1251.

Albanesi C, Scarponi C, Cavani A, Federici M, Nasorri F, Girolomoni G: Interleukin-17 is produced by both Th1 and Th2 lymphocytes, and modulates interferon-γ and interleukin-4 induced activation of human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2000, 115: 81-87. 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00041.x.

Jovanovic DV, DiBattista JA, Martel-Pelletier J, Jolicoeur FC, He Y, Zhang M, Mineau F, Pelletier J-P: IL-17 stimulates the production and expression of proinflammatory cytokines, IL-1β and TNFα, by human macrophages. J Immunol. 1998, 160: 3513-3521.

Chabaud M, Fossiez F, Taupin JL, Miossec P: Enhancing effect of IL-17 on IL-1-induced IL-6 and leukemia inhibitory factor production by rheumatoid arthritis synoviocytes and its regulation by Th2 cytokines. J Immunol. 1998, 161: 409-414.

Katz Y, Nadiv O, Beer Y: Interleukin-17 enhances tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced synthesis of interleukin 1, 6, and 8 in skin and synovial fibroblasts: a possible role as a 'fine-tuning cytokine' in inflammation processes. Arthritis Rheum. 2001, 44: 2176-2184. 10.1002/1529-0131(200109)44:9<2176::AID-ART371>3.0.CO;2-4.

Chabaud M, Miossec P: The combination of tumor necrosis factor alpha blockade with interleukin-1 and interleukin-17 blockade is more effective for controlling synovial inflammation and bone resorption in an ex vivo model. Arthritis Rheum. 2001, 44: 1293-1303. 10.1002/1529-0131(200106)44:6<1293::AID-ART221>3.0.CO;2-T.

Lubberts E: The role of IL-17 and family members in the pathogenesis of arthritis. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2003, 4: 572-577.

Nakae S, Nambu A, Sudo K, Iwakura Y: Suppression of immune induction of collagen-induced arthritis in IL-17-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2003, 171: 6173-6177.

Nakae S, Saijo S, Horai R, Sudo K, Mori S, Iwakura Y: IL-17 production from activated T cells is required for the spontaneous development of destructive arthritis in mice deficient in IL-1 receptor antagonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003, 100: 5986-5990. 10.1073/pnas.1035999100.

Lubberts E, Joosten LAB, Oppers B, Van den Bersselaar L, Coenen-de Roo CJ, Kolls JK, Schwarzenberger P, Van de Loo FA, Van den Berg WB: IL-1-independent role of IL-17 in synovial inflammation and joint destruction during collagen-induced arthritis. J Immunol. 2001, 167: 1004-1013.

Lubberts E, Koenders MI, Oppers-Walgreen B, Van den Bersselaar L, Coenen-de Roo CJJ, Joosten LAB, Van den Berg WB: Treatment with a neutralizing anti-murine interleukin-17 antibody after the onset of collagen-induced arthritis reduces joint inflammation, cartilage destruction, and bone erosion. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 50: 650-659. 10.1002/art.20001.

Lubberts E, Joosten LAB, Van de Loo FA, Schwarzenberger P, Kolls JK, Van den Berg WB: Overexpression of IL-17 in the knee joint of collagen type II immunized mice promotes collagen arthritis and aggravates joint destruction. Inflamm Res. 2002, 51: 102-104.

Chabaud M, Lubberts E, Joosten L, Van den Berg W, Miossec P: IL-17 derived from juxta-articular bone and synovium contributes to joint degradation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. 2001, 3: 168-177. 10.1186/ar294.

Lubberts E, Joosten LAB, Van de Loo FAJ, Van den Bersselaar L, Van den Berg WB: Reduction of interleukin-17-induced inhibition of chondrocyte proteoglycan synthesis in intact murine articular cartilage by interleukin-4. Arthritis Rheum. 2000, 43: 1300-1306. 10.1002/1529-0131(200006)43:6<1300::AID-ANR12>3.0.CO;2-D.

Dudler J, Renggli-Zulliger N, Busso N, Lotz M, So A: Effect of interleukin-17 on proteoglycan degradation in murine knee joints. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000, 59: 529-532. 10.1136/ard.59.7.529.

Cai L, Yin JP, Starovasnik MA, Hogue DA, Hillan KJ, Mort JS, Filvaroff EH: Pathways by which interleukin 17 induces articular cartilage breakdown in vitro and in vivo. Cytokine. 2001, 16: 10-21. 10.1006/cyto.2001.0939.

Chabaud M, Garnero P, Dayer JM, Guerne PA, Fossiez F, Miossec P: Contribution of interleukin 17 to synovium matrix destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. Cytokine. 2000, 12: 1092-1099. 10.1006/cyto.2000.0681.

Benderdour M, Tardif G, Pelletier JP, Di Battista JA, Reboul P, Ranger P, Martel-Pelletier J: Interleukin 17 (IL-17) induces collagenase-3 production in human osteoclastic chondrocytes via AP-1 dependent activation: differential activation of AP-1 members by IL-17 and IL-1β. J Rheum. 2002, 29: 1262-1272.

Koshy PJ, Henderson N, Logan C, Life PF, Cawston TE, Rowan AD: Interleukin 17 induces cartilage collagen breakdown: novel synergistic effects in combination with proinflammatory cytokines. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002, 61: 704-713. 10.1136/ard.61.8.704.

Van den Berg WB: Anti-cytokine therapy in chronic destructive arthritis. Arthritis Res. 2001, 3: 18-26. 10.1186/ar136.

Attur MG, Patel RN, Abramson SB, Amin AR: Interleukin-17 up-regulation of nitric oxide production in human osteoarthritis cartilage. Arthritis Rheum. 1997, 40: 1050-1053.

Martel-Pelletier J, Mineau F, Jovanovic D, Di Battista JA, Pelletier JP: Mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor κB together regulate interleukin-17-induced nitric oxide production in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes: possible role of transactivating factor mitogen-activated protein kinase-activated protein kinase (MAPKAPK). Arthritis Rheum. 1999, 42: 2399-2409. 10.1002/1529-0131(199911)42:11<2399::AID-ANR19>3.0.CO;2-Y.

LeGrand A, Fermor B, Fink C, Pisetsky DS, Weinberg JB, Vail TP, Guilak F: Interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin-17 synergistically up-regulate nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2 production in explants of human osteoarthritic knee menisci. Arthritis Rheum. 2001, 44: 2078-2083. 10.1002/1529-0131(200109)44:9<2078::AID-ART358>3.0.CO;2-J.

Van Bezooijen RL, Van der Wee-Pals L, Papapoulos SE, Lowik CW: Interleukin 17 synergizes with tumour necrosis factor alpha to induce cartilage destruction in vitro. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002, 61: 870-876. 10.1136/ard.61.10.870.

Schalkwijk J, Van den Berg WB, Joosten LAB, Van den Putte LBA: Elastase secreted by activated polymorphonuclear leukocytes causes chondrocyte damage and matrix degradation in intact articular cartilage: escape from inactivation by alpha-1-proteinase inhibitor. Br J Exp Pathol. 1987, 68: 81-88.

Campbell EJ, Silverman EK, Campbell MA: Elastase and cathepsin G of human monocytes: quantification of cellular content, release in response to stimuli, and heterogeneity in elastase-mediated proteolytic activity. J Immunol. 1989, 143: 2961-2968.

Bezooijen R, Farih-Sips HC, Papapoulos SE, Lowik CW: Interleukin-17: a new bone acting cytokine in vitro. J Bone Min Res. 1999, 14: 1513-1521.

Kong YY, Yoshida H, Sarosi I, Tan HL, Timms E, Capparelli C, Morony S, Oliveira-dos-Santos AJ, Van G, Itie A, et al: OPGL is a key regulator of osteoclastogenesis, lymphocyte development and lymph-node organogenesis. Nature. 1999, 397: 315-323. 10.1038/16852.

Dougall WC, Glaccum M, Charrier K, Rohrbach K, Brasel K, De Smedt T, Daro E, Smith J, Tometsko ME, Maliszewski CR, et al: RANK is essential for ostoclast and lymph node development. Genes Dev. 1999, 13: 2412-2424. 10.1101/gad.13.18.2412.

Simonet WS, Lacey DL, Dunstan CR, Kelley M, Chang MS, Luthy R, Nguyen HQ, Wooden S, Bennett L, Boone T, et al: Osteoprotegerin: a novel secreted protein involved in the regulation of bone density. Cell. 1997, 89: 309-319. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80209-3.

Lubberts E, Joosten LAB, Chabaud M, Van den Bersselaar L, Oppers B, Coenen-de Roo CJJ, Richards CD, Miossec P, Van den Berg WB: IL-4 gene therapy for collagen arthritis suppresses synovial IL-17 and osteoprotegerin ligand and prevents bone erosion. J Clin Invest. 2000, 105: 1697-1710.

Bush KA, Farmer KM, Walker JS, Kirkham BW: Reduction of joint inflammation and bone erosion in rat adjuvant arthritis by treatment with interleukin-17 receptor IgG1 Fc fusion protein. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 46: 802-805. 10.1002/art.10173.

Lubberts E, Van den Bersselaar L, Oppers-Walgreen B, Schwarzenberger P, Coenen-de Roo CJJ, Kolls JK, Joosten LAB, Van den Berg WB: IL-17 promotes bone erosion in murine collagen-induced arthritis through loss of the RANKL/OPG balance. J Immunol. 2003, 170: 2655-2662.

Laan M, Cui ZH, Hoshino H, Lotvall J, Sjostrand M, Gruenert DC, Skoogh BE, Linden A: Neutrophil recruitment by human IL-17 via C-X-C chemokine release in the airways. J Immunol. 1999, 162: 2347-2352.

Hurst SD, Muchamuel T, Gorman DM, Gilbert JM, Clifford T, Kwan S, Menon S, Seymour B, Jackson C, Kung TT, et al: New IL-17 family members promote Th1 or Th2 responses in the lung: in vivo function of the novel cytokine IL-25. J Immunol. 2002, 169: 443-453.

Fujino S, Andoh A, Bamba S, Ogawa A, Hata K, Araki Y, Bamba T, Fujiyama Y: Increased expression of interleukin 17 in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2003, 52: 65-70. 10.1136/gut.52.1.65.

Katz Y, Nadiv O, Beer Y: Interleukin-17 enhances tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced synthesis of interleukin 1, 6, and 8 in skin and synovial fibroblasts: a possible role as a 'fine-tuning cytokine' in inflammation processes. Arthritis Rheum. 2001, 44: 2176-2184. 10.1002/1529-0131(200109)44:9<2176::AID-ART371>3.0.CO;2-4.

Toda M, Leung DY, Molet S, Boguniewicz M, Taha R, Christodoulopoulos P, Fukuda T, Elias JA, Hamid QA: Polarized in vivo expression of IL-11 and IL-17 between acute and chronic skin lesions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003, 111: 75-81. 10.1067/mai.2003.1414.

Katz Y, Nadiv O, Rapoport MJ, Loos M: IL-17 regulates gene expression and protein synthesis of the complement system, C3 and factor B, in skin fibroblasts. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000, 120: 22-29. 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01199.x.

Schwarzenberger P, La Russa V, Miller A, Ye P, Huang W, Zieske A, Nelson S, Bagby GJ, Stoltz D, Mynatt RL, et al: IL-17 stimulates granulopoiesis in mice: use of an alternate, novel gene therapy-derived method for in vivo evaluation of cytokines. J Immunol. 1998, 161: 6383-6389.

Numasaki M, Fukushi J, Ono M, Narula SK, Zavodny PJ, Kudo T, Robbins PD, Tahara H, Lotze MT: Interleukin-17 promotes angiogenesis and tumor growth. Blood. 2003, 101: 2620-2627. 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1461.

Antonysamy MA, Fanslow WC, Fu F, Li W, Qian S, Troutt AB, Thomson AW: Evidence for a role of IL-17 in organ allograft rejection: IL-17 promotes the functional differentiation of dendritic cell progenitors. J Immunol. 1999, 162: 577-584.

Ye P, Rodriguez FH, Kanaly S, Stocking KL, Schurr J, Schwarzenberger P, Oliver P, Huang W, Zhang P, Zhang J, et al: Requirement of interleukin 17 receptor signaling for lung CXC chemokine and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor expression, neutrophil recruitment, and host defence. J Exp Med. 2001, 194: 519-527. 10.1084/jem.194.4.519.

Pan G, French D, Mao W, Maruoka M, Risser P, Lee J, Foster J, Aggarwal S, Nicholes K, Guillet S, et al: Forced expression of murine IL-17E induces growth retardation, jaundice, a Th2-biased response, and multiorgan inflammation in mice. J Immunol. 2001, 167: 6559-6567.

Kato T, Furumoto H, Ogura T, Onishi Y, Irahara M, Yamano S, Kamada M, Aono T: Expression of IL-17 mRNA in ovarian cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001, 282: 735-738. 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4618.

Tartour E, Fossiez F, Joyeux L, Galinha A, Gey A, Claret E, Sastre-Garau X, Couturier J, Mosseri V, Vives V, et al: Interleukin-17, a T-cell-derived cytokine, promotes tumorigenicity of human cervical tumors in nude mice. Cancer Res. 1999, 59: 3698-3604.

Lock C, Hermans G, Pedotti R, Brendolan A, Schadt E, Garren H, Langer-Gould A, Strober S, Cannella B, Allard J, et al: Gene-microarray analysis of multiple sclerosis lesions yields new targets validated in autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nat Med. 2002, 8: 500-508. 10.1038/nm0502-500.

Kurasawa K, Hirose K, Sano H, Endo H, Shinkai H, Nawata Y, Takabayashi K, Iwamoto I: Increased interleukin-17 production in patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000, 43: 2455-2463. 10.1002/1529-0131(200011)43:11<2455::AID-ANR12>3.0.CO;2-K.

Starnes T, Broxmeyer HE, Robertson MJ, Hromas R: Cutting edge: IL-17D, a novel member of the IL-17 family, stimulates cytokine production and inhibits hemopoiesis. J Immunol. 2002, 169: 642-646.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Veni Fellowship of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) grant 906-02-038 (E Lubberts) and a Dutch Arthritis Association Grant NR 00-1-302.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lubberts, E., Koenders, M.I. & van den Berg, W.B. The role of T cell interleukin-17 in conducting destructive arthritis: lessons from animal models. Arthritis Res Ther 7, 29 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1186/ar1478

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/ar1478