Abstract

Studies on immunological reconstitution after immune ablation and stem-cell therapy may yield important clues to our understanding of the pathogenesis of human autoimmune disease, due to the profound effects of function and organization of the immune system. Such studies are also indispensable when linking clinical sequelae such as opportunistic infections to the state of immune deficiency that ensues after the treatment. Much has been learnt on these issues from comparable studies in haemato-oncological diseases, although it remains to be proven that the data obtained from these studies can be extrapolated to rheumatological autoimmune diseases. Preliminary results from pilot studies in various rheumatological conditions not only pointed to clinical efficacy of the new treatment modality but also unveiled marked effects on T-cell receptor repertoires of circulating T lymphocytes, on titres of autoantibodies and T- and B-cell subsets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The emergence of high-dose immunosuppressive therapy (HDIT), followed by autologous haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (SCT) as a new treatment modality for selected patients with systemic rheumatic diseases is based on a pivotal role of the immune system in the course of such diseases [1*]. The aim is to maximally suppress or ablate the immune system and then rescue the patient from prolonged cytopenias or haematopoietic failure by infusing haematopoietic progenitor cells (CD34+ cells). Studies in experimental models of autoimmune disease in particular have lent support to the concept that autoreactive T lymphocytes can be eliminated by (myelo)lymphoablative chemo(radio)therapy, and that the subsequent transplantation of pluripotent haematopoietic stem cells gives rise to the emergence of naïve T lymphocytes that are tolerant to self-antigens (reviewed in this issue by van Bekkum [2]).

In humans, the pathogenesis of systemic rheumatic diseases is less well understood due to uncertainties regarding the nature of autoantigens, pathogenic roles of specific T and B lymphocytes, and complexity of cell-cell interactions. Study of the reconstituting immune system in relation to the disease course after HDIT and SCT may, however, yield important insights into the pathogenesis of these diseases because of the temporary profound effects of myeloablative or lymphoablative therapy on the immune system. This holds true for autologous SCT in particular, because it entails neither histoincompatibility (with its attendant risk for graft-versus-host disease) nor the use of immunosuppressive drugs to control such histoincompatibility.

Clinical considerations also stress the need to incorporate monitoring of immune reconstitution in any treatment protocol. It is well appreciated that the risks associated with HDIT and SCT in terms of morbidity and mortality are determined by numerical recovery of bone marrow cellular elements on the one hand, and functional recovery of cellular interactions on the other. These surrogate parameters of immunological reconstitution in turn depend on the treatment protocol employed. Current trials involve regimens that range from HDIT (eg cyclophosphamide) alone to (myelo)lymphoablative conditioning, in combination with SCT and vigorous T-cell depletion [3*]. It can be anticipated that the more intensive the treatment is, the higher the risks, because of a temporary lack of functional T lymphocytes after treatment. Regeneration of adequate T-cell numbers and repertoire diversity is a key element in the recovery of immune competence. In the absence of such recovery, susceptibility to opportunistic infections is increased.

The present review focuses on reconstitution of the various components of the immune system after HDIT and SCT, with emphasis on the determinants of immune reconstitution (Table 1). Special attention is paid to reconstitution of CD4+ T lymphocytes, which are considered to be key players in many autoimmune diseases [4].

To date only scarce data on immune reconstitution exist in patients with rheumatic disease, most of whom have been treated with (myelo)lymphoablative chemo(radio)therapy and autologous SCT obtained by mobilization of peripheral blood stem cells. In contrast, many data have been gathered in patients with haematological or oncological disease treated with HDIT alone or HDIT followed by either autologous or allogeneic SCT. These studies involved different diseases and heterogeneous treatment protocols with regard to source of stem cells (blood versus bone marrow), and mobilization and conditioning regimens. Thus, the data generated in these studies should be interpreted with the understanding that the overall effect of a treatment protocol on immune reconstitution is the sum of various interventions. However, some basic principles seem to govern reconstitution of the immune system after HDIT (with or without SCT), most notably pertaining to T and B lymphocytes [5**].

T- and B-lymphocyte reconstitution

Theoretically, the T-lymphocyte population after HDIT and SCT can be regenerated with T lymphocytes from four sources: from expansion of T cells that are reinfused along with the stem cells; from transfused or residual stem cells through a process of thymic education, comparable to what happens in early childhood; from stem cells through an extrathymic pathway; and from residual memory T cells that survive the conditioning regimen.

Obviously, in case of HDIT alone, reconstituting T lymphocytes can only be derived from either endogenous stem cells or mature T lymphocytes that have survived the treatment. Age (which is associated with diminished thymopoiesis) and the extent of T-cell depletion (by in vivo or ex vivo manipulation of the graft or by [myelo]lymphoablation) are the major determinants of the relative contributions of these sources to the recovery of T-lymphocyte population after HDIT and SCT [5**]. This is reflected mainly in the CD4+ lymphocyte compartment, as assessed by immunophenotyping of circulating T cells. Naïve CD4+ T lymphocytes bear the CD45RA isoform, whereas memory CD4+ T lymphocytes express the CD45RO isoform. The level of naïve (CD45RA+) CD4+ cells drops rapidly after HDIT (whether followed by SCT or not) and recovers slowly, whereas levels of memory (CD45RO+) CD4+ and CD8+ cells recover more rapidly, and sometimes even 'overshoot' [6*,7,8*]. As a result, a prolonged T-cell subset imbalance with inverted CD4:CD8 ratios is found that can last for longer than a year, depending on the protocol.

These differential effects are explained by differences in maturation pathways for T-cell subsets. In principle, reconstitution of the naïve T-cell compartment is achieved by thymus-dependent and thymus-independent pathways. The development of naïve CD4+ T lymphocytes from stem cells has been shown to be mainly thymus dependent. The observation of an inverse correlation between the size of the thymus and the level of the CD4+cells in the peripheral blood after HDIT (without SCT) supports the notion that CD4+ development depends on residual thymus function [9*]. Additional evidence was recently obtained by T-cell receptor (TCR) recombination excision circle analysis [10*], which showed that thymic output of immature naïve CD4+ T lymphocytes decreases rapidly early in life, and stabilizes at a low level after adolescence and until old age. In contrast, levels of circulating memory CD4+ T lymphocytes and of CD8+ T lymphocytes are not severely affected by HDIT and SCT. This is because thymus-independent maturation pathways dictate the regeneration of CD8+ T lymphocytes comprising both extrathymic lymphopoiesis from haematopoietic precursors and peripheral expansion of mature CD8+T cells, especially the CD8+CD28- subset [6*].

Cotransfused or residual memory CD4+ T cells also expand during the first months after transplantation [11,12*]. The peripheral expansion of mature T lymphocytes observed after HDIT (with or without SCT) has been attributed in part to the encounters with viruses, and is reflected by the elevated expression of activation markers CD25, CD38 and most notably human leucocyte antigen-DR [13,14]. The wave of activated memory CD4+T lymphocytes subsequently subsides due to increased susceptibility to apoptosis [15*]. In the autologous transplant setting it is difficult to determine the precise origin (cotransfused or residual) of this early expanded T-cell pool. Data from studies in recipients of T-cell-depleted allogeneic bone marrow transplant (BMT) [11,12*,16**] indicate that the early post-transplant T-cell compartment has a mixed origin, with T cells derived from both transferred donor T cells and surviving host T cells. In contrast, in patients who underwent unmanipulated BMT, only few recipient T-cell clones were detected, and most were of donor origin. It is likely that similar competing mechanisms apply in the autologous setting. In keeping with this is the observation that recovery of total numbers of circulating CD4+ T lymphocytes after HDIT and SCT is related to the number of T lymphocytes present in the graft. T-cell depletion or CD34+ stem-cell enrichment of a graft leads to delayed CD4 lymphocyte recovery, and CD4 lymphocyte recovery occurs more rapidly after autologous peripheral blood SCT than after autologous BMT because higher numbers of lymphocytes in the former graft [13,16**,17*].

Whatever the origin of these early memory T cells, the initial expansion of a limited number of mature T-cell clones results in a skewed oligoclonal repertoire, whereas subsequent diversification of TCR repertoires after T-cell-depleted SCT is dependent on the capacity of the thymus to generate naïve thymic emigrants [18*,19]. Molecular analysis of TCR repertoires by CDR3 size spectratyping has revealed differences in T-cell populations isolated before and after transplantation with CD34+-enriched autologous peripheral blood stem cells, possibly in response to antigenic stimuli or to a stochastic process [20**].

Analogous to repopulating T lymphocytes, post-transplant B lymphocytes are derived from either cotransfused or residual B cells, or from transplanted or residual stem cells, depending on the treatment regimen employed. The documented transfer of humoral immunity in allogeneic transplantation suggests that differentiated antigen-selected B cells in the graft can be a significant contributor to post-transplant B cells, whereas residual B cells have also been demonstrated to contribute [5**]. Finally, immunophenotyping data lend support to a role of stem cells as a source of post-transplant circulating B cells. After an initial drop in circulating CD19+ and CD20+ mature B cells, B cells emerge with an undifferentiated phenotype. In the case of CD34+-selected SCT, an over-representation of CD5+CD19+ B cells can be detected during the early post-transplant period, but the significance of this is not well understood [20**]. Although the regeneration of B cells after transplantation has been interpreted as a recapitulation of foetal ontogeny, this has been disputed on the basis of structural differences in B-cell receptor repertoires [21].

Functional effects of immune ablation and stem cell therapy

HDIT and SCT not only affects numbers and repertoires of T and B lymphocytes, but induces functional changes as well. Defective T-cell proliferative responses to mitogens, and TCR-crosslinking antibodies may partly be caused by high numbers of monocytes that are present in growth factor-mobilized peripheral blood-derived SCT, or by type 2-associated cytokines [22,23,24]. Defective in vitro production of IL-2, IL-10 and IFN-γ, but not of IL-4, by peripheral blood mononuclear cells during the first 6 months after HDIT and SCT has also been demonstrated, although the data on IL-10 are conflicting [25,26]. An early expansion of a memory CD4+CD7-T-cell subset with preferential IL-4 production has been detected after HDIT and SCT, but not after HDIT alone [27]. The in vivo degree of T-cell incompetence after HDIT and SCT is difficult to gauge exactly in vitro, however. Deficiences in humoral responses after HDIT and SCT are attributed both to decreased T-cell help and intrinsic B-cell defects.

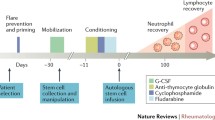

Immunological monitoring in patients with systemic rheumatic disease

Studies on immune reconstitution after HDIT (with or without SCT) in patients suffering from severe rheumatological conditions have only recently started to emerge [28]. These conditions predominantly include rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis and juvenile chronic arthritis. Different protocols are being employed to treat these conditions, varying from HDIT alone to (myelo)lymphoablation followed by autologous SCT and in vivo T-cell depletion with antithymocyte globulin or Campath (LeukoSite Inc, Cambridge, MA, USA) monoclonal antibody or ex vivo graft manipulation [3*].

The aim of graft manipulation is to minimize the risk of re-infusing autoreactive T lymphocytes. To this end, the graft is purged of T cells by monoclonal antibodies or enriched for CD34+ stem cells. In the latter case, monocytes, natural killer cells and B cells are de facto depleted from the graft also.

Obviously, different regimens will produce different results on immune reconstitution. The data generated thus far seem generally comparable to those obtained in haemato-oncological diseases with respect to immunophenotyping of circulating mononuclear cells. The bottom line is that recovery of natural killer cells and monocytes after HDIT and SCT is prompt, but that numerical and functional recovery of lymphoid and immune effector cells occurs more gradually.

In three RA patients, mobilization of haematopoietic stem cells with HDIT and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) alone led to a drop in the number of circulating CD45RA+ naïve T lymphocytes, whereas the number of circulating memory cells was more stable [29]. transient decrease in rheumatoid factor (RF) level was reported. Interestingly, an increase in the level of circulating CD4+CD7- T cells appeared to be associated with disease relapse. This T-cell subset is suspected of playing a role in the pathogenesis of RA [30]. It would be of interest to assess the cytokine profile of this subset in these patients, in the light of the above-mentioned preferential IL-4 production of this subset in patients with haematological diseases.

HDIT with unmanipulated SCT led to substantial clinical responses in four RA patients, concomitant with moderate depressions of RF levels in blood [31]. The persistence of RF positivity cannot solely be explained by the putative reinfusion of autoaggressive lymphocytes, because HDIT without SCT had comparable effects [32].

In another study [33**], a patient with RA was treated with a myeloablative conditioning regimen, followed by SCT that was T-cell depleted and CD34+enriched. Enumeration by flow cytometry of CD4+ T cells expressing TCRs of different Vβ families showed a restoration of T-cell diversity compared with the major skewing seen 3 months after transplantation, but with differences in the relative contributions of the families in pre- and post-transplant repertoires. In vitro T-cell proliferative responsiveness and delayed-type skin hypersensitivity to a recall antigen returned to pretransplant levels.

A sustained clinical response was achieved in two out of four RA patients treated with HDIT (cyclophosphamide), antithymocyte globulin and positively selected SCT [34]. RF was only slightly reduced in three patients, but disappeared at 6 months in one of the responder patients. The same treatment in two lupus patients led to an initial decrease in antinuclear antibody titres and antidoublestranded DNA antibodies, concomitant with a clinical response. In a girl with systemic sclerosis a marked and sustained improvement in skin score and general well-being was observed 2 years after the transplantation procedure [35]. No correlation was found with the results of in vitro proliferation tests and immunophenotyping of circulating mononuclear cells. The persistence of autoantibodies (antinuclear and anti-Scl70) suggested that not all autoimmune clones were eradicated.

Conclusion

The present data do not allow firm conclusions to be drawn regarding the correlation of clinical responses and results of immunological monitoring. At this point it must be recalled that, in RA patients, therapies with anti-CD4 monoclonal antibodies were not very effective, despite prolonged depletion of circulating CD4+ T lymphocytes [36]. As a possible mechanism it was shown [37] that IFN-γ producing memory CD4+ T lymphocytes were spared by this treatment and that CD4+ T lymphocytes persist in the joints. Other studies in RA [38] have also demonstrated lack of correlation between numbers of circulating cells and clinical responses, with persistence of synovial mononuclear cell infiltrates.

From a critic's viewpoint, eradication of autoreactive memory T and B lymphocytes by autologous SCT may be impossible, and allogeneic SCT may be necessary to achieve this goal. A cure may also remain elusive if rheumatic diseases originate in stem-cell defects, as has been mooted for RA and systemic lupus erythematosus [39]. Optimists are supported by the beneficial clinical effects observed thus far. In any case, an extensive search for mechanisms that underlie the remissions observed in many patients, and the relapses that occurred in others seems justified. Whether these mechanisms turn out to be only related to rigorous modulation of the immune system, or whether effects on nonimmune cells are also involved needs to be investigated [40]. It is up to the rheumatologists and immunologists to proceed by close collaboration, preferentially across institutional and national borders, to address the fundamental questions associated with this new treatment modality.

References

Snowden JA, Brooks PM, Biggs JC: Haemopoietic stem cell transplantation for autoimmune disaeses. Br J Haematol. 1997, 99: 9-22. 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.3273144.x. This is a comprehensive review on the theoretical considerations, preclinical animal models, and anecdotal reports of long-term remissions of autoimmune disease observed in patients transplanted for concomitant malignancy.

van Bekkum DW: Immune ablation and stem-cell therapy in autoimmune disease: experimental basis for autologous stem-cell transplantation in autoimmune disease. Arthritis Res. 2000, 2: 281-284. 10.1186/ar103.

Tyndall A, Fassas A, Passweg J, et al: Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplants for autoimmune disease: feasibility and transplant-related mortality. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999, 24: 729-734. 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701987. This recent update shows the feasibility of different treatment protocols employed in 74 patients with autoimmune disease, half of whom had rheumatological disease. Overall treatment-related mortality at 1 year was 9%.

Breedveld FC: New insights in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1998, 25(Suppl 53): S3-S7. This is an extensive review of immunological data obtained in patients with haemato-oncological diseases, elaborating on the variables involved in SCT, including the effects on immune reconstitution.

Guillaume T, Rubinstein DB, Symann M: Immune reconstitution and immunotherapy after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 1998, 92: 1471-1490.

Mackall CL, Fleisher TA, Brown MR, et al: Distinctions between CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell regenerative pathways result in prolonged T-cell subset imbalance after intensive chemotherapy. Blood. 1997, 89: 3700-3707. Intensive chemotherapy alone caused a profound age-related decline in the rate of CD4+ T-cell regeneration in adult patients with haemato-oncological malignancy. Reconstitution was enhanced in patients with thymic enlargement after chemotherapy. In contrast CD8+ T-cell numbers were not affected by advancing age and absent thymic enlargement after intensive chemotherapy.

Koehne G, Zeller W, Stockschlaeder M, Zander AR: Phenotype of lymphocyte subsets after autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997, 19: 149-156. 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700624.

Roberts MM, To LB, Gillis D, et al: Immune reconstitution following peripheral blood stem cell transplantation, autologous bone marrow transplantation and allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1993, 12: 469-475. In patients with a haematological malignancy, recovery of total lymphocyte count, and total number of CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ cells was higher after peripheral blood SCT than after allogeneic BMT, with intermediate results after autologous BMT.

Mackall CL, Fleisher TA, Brown MR, et al: Age, thymopoiesis, and CD4+ T-lymphocyte regeneration after intensive chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 1995, 332: 143-149. 10.1056/NEJM199501193320303. In patients who had undergone intensive chemotherapy for cancer, thymusdependent regeneration of CD4+ T lymphocytes was shown to occur primarily in children displaying ‘thymic rebound’, whereas even adolescent persons had deficiencies in this pathway.

Douek DC, McFarland RD, Keiser PH, et al: Changes in thymic function with age and during the treatment of HIV infection. Nature. 1998, 396: 690-695. 10.1038/25374. This report outlines the application of new technique to assess T-cell neogenesis: TCR recombination excision circles, measured quantitatively by polymerase chain reaction methods. Although thymic function declined with age, substantial output of naïve CD4+ T cells was maintained into late adulthood. Highly active antiretroviral therapy resulted in increased output in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection.

Mackall CL, Gress RE: Pathways of T-cell regeneration in mice and humans: implications for bone marrow transplantation and immunotherapy. Immunol Rev. 1997, 157: 61-72.

Diviné M, Boutolleau D, Delfau-Larue MH, et al: Poor lymphocyte recovery following CD34-selected autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Br J Haematol . 1999, 105: 349-360. 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01344.x. This recent study showed, by immunophenotyping, that all lymphocyte subsets (notably CD4+), except the natural killer subset, remained subnormal at 12 months after autologous transplantation with CD34+ selected stem cells. All eight patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma had bone marrow infiltration, which may have influenced the results.

Talmadge JE, Reed E, Ino K, et al: Rapid immunologic reconstitution following transplantation with mobilized peripheral blood stem cells as compared to bone marrow. Bone Marrow Transplant . 1997, 19: 161-172. 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700626.

Hakim FT, Cepeda R, Kaimei S, et al: Constraints on CD4 recovery postchemotherapy in adults: thymic insufficiency and apoptotic decline of expanded peripheral CD4 cells. Blood. 1997, 90: 3789-3798.

Singh RK, Varney ML, Buyukberber S, et al: Fas-FasL-mediated CD4+ T-cell apoptosis following stem cell transplantation. Cancer Res. 1999, 59: 3107-3111. Preferential deletion of Fas+ CD4+ T lymphocytes due to interaction with Fas ligand-expressing monocytes in patients undergoing high-dose chemotherapy could be a mechanism in the peripheral tolerance observed in breast cancer patients after high-dose chemotherapy and autologous SCT.

Roux E, Helg C, Dumont-Girard F, et al: Analysis of T-cell repopulation after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: significant differences between recipients of T-cell depleted and unmanipulated grafts. Blood. 1996, 87: 3984-3992. In patients with haematological malignancies, unmanipulated allogeneic bone marrow stem cell transplants produced a more diverse TCR repertoire than T-cell depleted transplants, especially during the first months of followup because of expansion of cotransfused T lymphocytes.

Martínez C, Urbano-Ispizua A, Rozman C, et al: Immune reconstitution following allogeneic peripheral blood progenitor cell transplantation: comparison of recipients of positive CD34+ selected grafts with recipients of unmanipulated grafts. Exp Hematol. 1999, 27: 561-568. 10.1016/S0301-472X(98)00029-0. During the first 6 months after allogeneic peripheral blood SCT with CD34+ selected grafts the number of CD4+, CD4+CD45RA+, and TCRgd+ cells was significantly lower than after unmanipulated allogeneic peripheral blood SCT in patients with haematological malignancies. However, no difference in the incidence of either bacterial or fungal infectious complications was observed.

Dumont-Girard F, Roux E, van Lier RA, et al: Reconstitution of the T-cell compartment after bone marrow transplantation: restoration of the repertoire by thymic emigrants. Blood. 1998, 92: 4464-4471. Five patients with a haematological malignancy were treated with allogeneic SCT and intensive graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis, including Campath monoclonal antibody. The peripheral T-cell pool was initially repopulated by expansion of cotransfused memory T cells, followed by TCR diversification with the advent of CD4+ thymic emigrants.

Godthelp BC, Van Tol MJD, Vossen JM, Van den Elsen PJ: T-cell immune reconstitution in pediatric leukemia patients after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation with T-cell depleted or unmanipulated grafts: evaluation of overall and antigen-specific T-cell repertoires. Blood. 1999, 94: 4358-4369.

Bomberger C, Singh-Jairam M, Rodey, et al: Lymphoid reconstitution after autologous PBSC transplantation with FACS-sorted CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors. Blood. 1998, 91: 2588-2600. Lymphoid reconstitution after myeloablative chemotherapy and CD34+- enriched autologous peripheral blood SCT was delayed compared with recipients of non-T-cell-depleted peripheral blood SCT. Furthermore, the former patient group displayed a reduced diversity of the peripheral T-cell repertoire in the early post-transplant period.

Raaphorst FM: Bone marrow transplantation, fetal B-cell repertoire development, and the mechanism of immune reconstitution. Blood. 1998, 92: 4873-4874.

Ageitos AG, Ino K, Ozerol I, Tarantolo S, Heimann DG, Talmadge JE: Restoration of T and NK cell function in GM-CSF mobilized stem cell products from breast cancer patients by monocyte depletion. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997, 20: 117-123. 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700864.

Talmadge JE, Reed EC, Kessinger A, et al: Immunologic attributes of cytokine mobilised peripheral blood and recovery following transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996, 17: 101-109.

Singh RK, Ino K, Varney M, Heimann D, Talmadge JE: Immunoregulatory cytokines in bone marrow and peripheral blood stem cell products. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999, 23: 53-62. 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701518.

Guillaume T, Sekhavat M, Rubinstein DB, et al: Defective cytokine production following autologous stem cell transplantation for solid tumors and hematologic malignancies regardless of bone marrow or peripheral origin and lack of evidence for a role for interleukin-10 in delayed immune reconstitution. Cancer Res. 1994, 54: 3800-3807.

Varney ML, Ino K, Ageitos AG, Heimann DG, Talmadge JE, Singh RK: Expression of interleukin-10 in isolated T cells and monocytes from growth factor-mobilized peripheral blood stem cell products: a mechanism of immune dysfunction. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1999, 19: 351-360. 10.1089/107999099314054.

Leblond V, Othman TB, Blanc C, et al: Expansion of CD4+ CD7- T cells, a memory subset with preferential interleukin-4 production, after bone marrow transplantation. Transplantation. 1997, 64: 1453-1459. 10.1097/00007890-199711270-00014.

Tyndall A, Gratwohl A: Immune ablation and stem-cell therapy in autoimmune disease: clinical experience. Arthritis Res. 2000, 2: 276-280. 10.1186/ar102.

Breban M, Dougados M, Picard F, et al: Intensified-dose (4 gm/m2) cyclophosphamide and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor administration for hematopoietic stem cell mobilization in refractory rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999, 42: 2275-2280. 10.1002/1529-0131(199911)42:11<2275::AID-ANR3>3.0.CO;2-6.

Schmidt D, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM: CD4+ CD7- CD28- T cells are expanded in rheumatoid arthritis and are characterized by autoreactivity. J Clin Invest. 1996, 97: 2027-2037.

Snowden JA, Biggs JC, Milliken ST, Fuller A, Brooks PM: A phase I/II dose escalation study of intensified cyclophosphamide and autologous blood stem cell rescue in severe, active rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999, 42: 2286-2292. 10.1002/1529-0131(199911)42:11<2286::AID-ANR5>3.0.CO;2-X.

Brodsky RA, Petri M, Smith DG, et al: Immunoablative high-dose cyclophosphamide without stem-cell rescue for refractory, severe autoimmune disease. Ann Intern Med. 1998, 129: 1031-1035.

Durez P, Toungouz M, Schandené L, Lambermont M, Goldman M: Remission and immune reconstitution after T-cell depleted stem-cell transplantation for rheumatoid arthritis [letter]. Lancet. 1998, 352: 881. Myeloablative conditioning followed by T-cell-depleted autologous SCT led to clinical remission in a patient with RA, and restoration of TCR repertoire (flow cytometry) and of in vitro and in vivo responsivess toward a recall antigen, proving that specific memory T cells survived conditioning or, less likely, were cotransfused.

Burt RK, Traynor AE, Pope R, et al: Treatment of autoimmune disease by intense immunosuppressive conditioning and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 1998, 10: 3505-3514.

Martini A, Maccario R, Ravelli A, et al: Marked and sustained improvement two years after autologous stem cell transplantation in a girl with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999, 42: 807-811. 10.1002/1529-0131(199904)42:4<807::AID-ANR26>3.0.CO;2-T.

Van der Lubbe PA, Dijkmans BA, Markusse HM, Nassander U, Breedveld FC: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of CD4 monoclonal antibody in early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995, 38: 1097-1106.

Rep MHG, van Oosten BW, Roos MTL, et al: Treatment with depleting CD4 monoclonal antibody results in a preferential loss of circulating naive T cells but does not affect IFN-γ secreting TH1 cells in humans. J Clin Invest. 1997, 99: 2225-2231.

Ruderman EM, Weinblatt ME, Thurmond LM, Pinkus GS, Gravallese EM: Synovial tissue response to treatment with CAMPATH-1H. Arthritis Rheum. 1995, 38: 254-258.

Berthelot J-M, Bataille R, Maugars Y, Prost A: Rheumatoid arthritis as a bone marrow disorder. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1996, 26: 505-514.

Wicks I, Cooley H, Szer J: Autologous hemopoietic stem cell transplantation. A possible cure for rheumatoid arthritis? . Arthritis Rheum. 1997, 40: 1005-1011.

Mills KC, Gross TG, Varney ML, et al: Immunologic phenotype and function in human bone marrow, blood stem cells and umbilical cord. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996, 18: 53-61. Mobilized peripheral blood stem cells obtained from cancer patients had an increased frequency of CD4+, CD45RO+ and CD56+ cells relative to bone marrow cells. All stem cell products had significant depression in T- and Bcell function as compared with normal blood mononuclear cells.

Rosillo MC, Ortuno F, Moraleda JM, et al: Immune recovery after autologous or rhG-CSF primed PBSC transplantation. Eur J Haematol. 1996, 56: 301-307.

Offner F, Kerre T, De Smedt M, Plum J: Bone marrow CD34+ cells generate fewer T cells in vitro with increasing age and following chemotherapy. Br J Haematol. 1999, 104: 801-808. 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01265.x.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Articles of particular interest have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van Laar, J.M. Immune ablation and stem-cell therapy in autoimmune disease Immunological reconstitution after high-dose immunosuppression and haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Arthritis Res Ther 2, 270 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1186/ar101

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/ar101