Abstract

Introduction

Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPS) include depressive symptoms, anxiety, apathy, sleep problems, irritability, psychosis, wandering, elation and agitation, and are common in the non-demented and demented population.

Methods

We have undertaken a systematic review of reviews to give a broad overview of the prevalence, course, biological and psychosocial associations, care and outcomes of BPS in the older or demented population, and highlight limitations and gaps in existing research. Embase and Medline were searched for systematic reviews using search terms for BPS, dementia and ageing.

Results

Thirty-six reviews were identified. Most investigated the prevalence or course of symptoms, while few reviewed the effects of BPS on outcomes and care. BPS were found to occur in non-demented, cognitively impaired and demented people, but reported estimates vary widely. Biological factors associated with BPS in dementia include genetic factors, homocysteine levels and vascular changes. Psychosocial factors increase risk of BPS; however, across studies and between symptoms findings are inconsistent. BPS have been associated with burden of care, caregiver's general health and caregiver depression scores, but findings are limited regarding institutionalisation, quality of life and disease outcome.

Conclusions

Limitations of reviews include a lack of high quality reviews, particularly of BPS other than depression. Limitations of original studies include heterogeneity in study design particularly related to measurement of BPS, level of cognitive impairment, population characteristics and participant recruitment. It is our recommendation that more high quality reviews, including all BPS, and longitudinal studies with larger sample sizes that use frequently cited instruments to measure BPS are undertaken. A better understanding of the risk factors and course of BPS will inform prevention, treatment and management and possibly improve quality of life for the patients and their carers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Behavioural and psychological symptoms (BPS) include depressive symptoms, anxiety, apathy, sleep problems, irritability, psychosis, wandering, elation and agitation. They are common in people with dementia, but are not restricted to this group [1]. BPS have public policy implications as they impact upon quality of life of older people and their carers, and influence prescribing and use of services [2, 3].

Systematic reviews are an important tool for summarising the available evidence regarding a specific topic, permitting policy decisions to be based on representative literature. They allow researchers to focus on areas where information is most lacking, and allow more reliable interpretation of research findings. A review of reviews, therefore, serves two important purposes: first, summarising the evidence base on a subject beyond the scope of a single review, and second, highlighting areas where the literature is inadequate and where additional reviews are required. While the prevalence, course, biological and psychosocial associations, care and outcomes of BPS have been the subject of systematic reviews, the findings from these different reviews have not been brought together in this way. Given the broad research focus on BPS, including underlying causes, association with dementia risk, and impact on care, and the large number of studies published in this area, any single systematic review of the primary literature can only explore a narrow range of objectives.

This paper presents a systematic 'review of reviews' of the literature on BPS in older people. Combining current knowledge across the multiple domains of BPS research provides a broad overview of what is known and identifies gaps where reviews have not been conducted [4]. Bringing together the conclusions of the reviews, we provide recommendations for future research and highlight areas where the evidence base with respect to BPS in the older population should be strengthened. In addition, we discuss the recommendations for future research made by the reviews.

Materials and methods

Scope of review

BPS are related to cognitive impairment and dementia. So-called "behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia", BPSD, are commonly studied within this subpopulation, but BPS can also occur in older people without significant cognitive impairment. Traditionally these are considered as phenomena distinct to BPSD; however, BPS in a cognitively healthy older person may indicate early dementia, and certain BPS, for example, depression, may be risk factors for dementia. Continuities in BPS are seen 'pre' and 'post' diagnosis, and common biological and psychosocial risk factors for BPS may exist among the cognitively healthy and cognitively impaired older populations. For this reason the scope of our review includes studies of BPS in the older population with or without cognitive impairment or dementia. We included reviews of the prevalence, the causes and consequences of BPS.

Owing to the breadth of literature and the specialist treatment required to review certain kinds of study, there are some limitations to the scope of this review. We did not include reviews that focused on pharmacological or non-pharmacological treatment of symptoms. Depression is a heterogeneous disorder ranging from mild symptoms to major depressive disorder. Depression is common in the older population with dementia and can be studied in the context of other BPS, but is also seen in the older population without dementia (Figure 1). Depression in the older population without dementia has been studied widely since it was first described in 1896 [5, 6]. The term BPSD was introduced by the International Psychogeriatric Association in 1996 [7]. Although they have been identified since the earliest descriptions of dementia, research only moved to BPSD in the 1980s with the development of instruments to measure BPSD [8, 9]. Depression as a BPSD and depression in the older population without dementia have largely been separate research areas. Here, we focused on depressive symptoms below the threshold for depressive disorder. We excluded reviews that studied only major or clinical depression and included reviews that studied both major depression and minor depression, depressive symptoms or minor depression only or depressive symptoms in the context of other BPS.

Search methods

Embase and Medline were searched for potentially relevant articles published before 29 March 2012. Search terms included Emtree terms and text searches for each individual BPS and BPS in general (see Additional file 1), and Dementia (Emtree) or Aged (Emtree). Additional articles were identified from reference lists of included studies and relevant narrative reviews.

Data collection

All systematic reviews written in English of one or more BPS in the older non-demented or demented population were included. A systematic review was defined as used by the Cochrane Collaboration and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement: "A review of a clearly formulated question that uses systematic and explicit methods to identify, select, and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect and analyse data from the studies that are included in the review. Statistical methods (meta-analysis) may or may not be used to analyse and summarise the results of the included studies" [10]. Specific symptoms included depressive symptoms (including sadness, tearfulness, being unhappy, depressed feeling, suicidal feelings), anxiety (including feelings and physical signs of anxiety, worrying, being frightened), apathy (including listlessness, loss of interest, slowing), sleep problems (includes reduced sleep, increased sleep, change in sleep, tiredness), irritability (including being irritable or angry, verbal and physical aggression), psychosis (including delusion and hallucination), wandering (including wandering away, getting lost, aimless wandering), elation (including euphoria, inappropriate laughing) and non-aggressive agitation (including restlessness, repetitive behaviour).

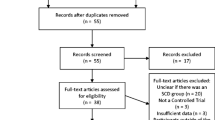

RvdL selected articles through a multi-step screening process first based upon the assessment of the title and the abstract, followed by assessment of the article content. Information from each potential article was extracted by RvdL using a standardised form, recording: the BPS investigated, population, date of publication and literature search, number of studies reviewed and if a meta-analysis was performed. Reviews were divided by the following themes: prevalence, progression, course, biological associations, risk factors, care, quality of life and disease outcome. Results were summarised using the abstract. A list of recommendations for future research (for example, "future research should", "we recommend", "is needed") and limitations of the original studies and review as reported by the reviews in their discussion section was generated.

The quality of the included reviews was assessed using AMSTAR, a validated measurement tool (Shea et al. 2007, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews [11, 12].

Results

Number of studies

Separate searches of each BPS resulted in 266 reviews for depressive symptoms (N = 156 in dementia), 110 for anxiety (N = 74 in dementia), 8 for apathy (N = 7 in dementia), 82 for sleep problems (N = 45 in dementia), 30 for irritability (N = 24 in dementia), 42 for psychosis (N = 33 in dementia), 3 for wandering (N = 3 in dementia), 3 for elation (N = 3 in dementia), 15 for agitation (N = 14 in dementia) and 29 for BPS (N = 28 in dementia). Altogether, 399 reviews were found. Of these, 28 reviews were included. The others were excluded because BPS were not the main focus of the paper, instead they studied treatment or non-pharmacological interventions, did not focus on elderly or dementia populations, were not performed systematically or did not meet any other inclusion criteria. Seven reviews were excluded because they only studied major depression [13–19]. Reference searches of the included systematic reviews and relevant narrative reviews identified nine additional reviews. Therefore, in total 36 reviews were included.

Characteristics and focus of included reviews

Tables 1 and 2 show the characteristics of the reviews included. Most (N = 13) [20–32] investigated the prevalence or co-occurrence of symptoms. Eleven [21, 27, 30, 33–40] reviewed the longitudinal course of BPS or its associations with incident dementia. Possible underlying biological factors were examined in nine reviews [41–49], as were psychosocial risk factors [20, 24, 26, 27, 30, 31, 49, 50]. Only two reviews [51, 52] focused on the associations between BPS and care outcomes, one [53] on the effects on quality of life and four [30, 32, 54, 55] on disease outcomes.

Figure 1 shows the populations and BPS that were the focus of the different reviews. As shown, most reviews focused on depression in the older population, not specifically excluding those with dementia (N = 11) [20, 29–31, 35, 43, 44, 46, 48, 50, 56], or depression and several other BPS in dementia (N = 6) [21, 22, 24, 26, 42, 52]. Of the studies focusing on depressive symptoms or other BPS in the older population, it was often unclear if those with dementia were included, with only few specifically including only studies of "healthy" or "normal" elderly [38, 39] or reporting which original studies excluded those with dementia or cognitive impairment [28, 35, 43, 57]. Overall, 12 reviews [20, 28–32, 41, 45, 48–50] included studies of the entire older population (> 50 years), 3 [35, 43, 44] of the older population but with some studies excluding those with dementia or cognitive impairment, 1 [23] of patients in long-term care, 3 [40, 46, 47] of an adult population including older aged adults, 2 [38, 39] that only included 'healthy' adults, and 3 included case control studies comparing those with dementia to normal controls [33, 36, 37]. In addition, 3 [21, 22, 24] studied cognitively impaired populations and 10 [25–27, 34, 42, 51–55] people with dementia. Nine reviews included a wide battery of BPS [21–24, 42, 51–54] and a further three [25, 26, 49] focused on a combination of two or more symptoms. Of those studying a single symptom, depressive symptoms were most widely reviewed (N = 18) [20, 28–31, 33–37, 41, 43–48, 50]. Sleep problems (N = 3) [38–40], psychosis (N = 2) [27, 55] and anxiety (N = 1) [32] were the subject of few reviews. Details of the characteristics and recruitment of the population of the original studies included in the reviews were often not reported.

Quality

The quality assessment for each included review is shown in Table 3. Generally, review quality was low, with only 7 of the reviews scoring positive on 5 of the 11 components and meeting the criteria for moderate scientific quality (5 to 8 points). All other reviews scored less than five points.

Narrative description by theme

Prevalence of BPS

Two reviews [21, 22] of BPS in populations with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) reported an overall symptom prevalence ranging from 35 to 75% and 35 to 85%. Depressive symptoms, anxiety and irritability were the most commonly observed symptoms, followed by apathy and agitation. Hospital-based samples of MCI cases reported a higher mean prevalence of any BPS than population-based studies [21]. In people with dementia in long term care the prevalence of one or more BPS was 78% [23]. The mean reported prevalence of psychosis in dementia was 41% [27].

Reviews of the prevalence of BPS in the older population without dementia were available only for depression. The prevalence of depressive disorders in the older population without dementia has been estimated to be 17.1% (95% CI 9.7 to 26.1), in a meta-analysis of moderate scientific quality [28]. Other studies reported a high variability in the prevalence reported in included studies ranging from 14 to 82% [23], 14 to 16% [20], 0 to 35% [58] and 7 to 49% [31]. A lower prevalence has been reported in community settings than in primary care and long term care settings [30].

Most reviews found considerable variability in reported prevalence, possibly due to heterogeneity in methodology, thereby limiting the ability to compare data. Recommendations include the use of standardised BPS instruments and the study of various populations.

Longitudinal course and association with cognitive decline

Monastero et al. reported that prospective studies showed that BPS, particularly depression, might represent risk factors for MCI or predictors of MCI conversion to dementia [21]. A review of moderate scientific quality failed to find evidence of an association between depressive symptoms and severity of dementia [34]. A review on psychotic symptoms suggested that these symptoms increase with the development of dementia but plateau after three years [59].

Few reviews on BPS course have been conducted in the older population. Huang et al. reported that compared to individuals without cognitive impairment, incidence and prevalence of depression was higher in those with cognitive impairment or dementia. Meeks et al. found that depression was relatively stable in the older population, with a median remission of 27% after more than one year [30]. Three reviews by Jorm et al. concluded that history of depression in cognitively normal persons was associated with increased risk of dementia [33, 36, 37, 60]. Sleep problems including sleep latency and waking after sleep were common with increasing age, but only sleep efficiency continued to significantly decrease after age 60 [38–40].

The reviews identified a need for more longitudinal studies using standardised measures of cognitive function and BPS and appropriate adjustment for confounding factors.

Biopsychosocial associations

Biological factors

A systematic review shows inconsistent results for genetic associations, including genes coding for APOE E, serotonin receptors and transporter, COMT, MAO-A, tryptophan hydroxylase and dopamine receptors with BPS in individuals with dementia [42]. No other reviews were found.

In the general older population, most reviews of biological correlates of BPS focus on depression. An association between high levels of homocysteine and depression and dementia has been reported [41, 45]. Stetler et al. suggest an association between depression and cortisol and other hormones [46]. In addition, cerebral atherosclerotic changes may result in cognitive impairment and depression, possibly mediated by C-reactive protein but results were not consistent [47]. The association between vascular factors and depression was further studied and discussed in a review by Camus et al. [48].

Recommendations for future research include prospective studies with large sample sizes further investigating the association with biological factors.

Risk factors

In nursing home patients with cognitive impairment, BPS were associated with the psychosocial environment, in addition to dementia type and stage and medication use [24]. In dementia patients, psychosis has been associated with age, illness duration and functional impairment, whereas results are weak or inconsistent for sociodemographic variables [27].

In two moderate quality reviews of the older population by Huang et al., depression was reported to be common in those with poor self-rated health, disability and chronic disease, including stroke, sensory impairment, cardiac disease or chronic lung disease [43, 44]. Depression is more common in women, and has been associated with many risk factors, including other diseases, low social support, cognitive impairment, disability, prior depression and bereavement [20, 29–31, 49, 50]. Vink et al. report that health factors were less clearly related to anxiety than to depression [49]. Psychosocial associations of other BPS have not been reviewed.

More research is recommended on risk factors for depression and randomised controlled trials to investigate if manipulation of risk factors reduces the onset of BPS.

Outcomes and care

Some evidence suggests that BPS predicts nursing home placement in those with dementia [51]. Burden of care, caregiver's general health and caregiver depression scores have been associated with BPS, but perhaps caregiver's perception of the BPS and caregiver's social and psychological resources prior to institutionalisation are more important factors [52]. Lee et al. concluded that there was no consensus regarding the association between BPS and increased mortality in individuals with dementia [54]. Studies of associations between delusions in dementia and functional outcome had inconsistent results [55]. Finally, depression has been associated with decreased health related quality of life in dementia, although the size of the association was moderate [53].

Depression in the general older population has been associated with increased health care utilisation and expenditure [30]. In addition, anxiety in the elderly has been reported to have negative consequences independently of depression [32].

The reviews recommend more research with better measurements of determinants and outcomes and more sophisticated techniques to analyse the association with disease outcomes.

Summary: limitations and recommendations

Overall, the reviews reported several limitations of the original studies, including heterogeneity in methodology, insufficient adjustment for confounders, heterogeneity in BPS instruments and definitions, small sample size and that most studies were cross-sectional (Figure 2). This led to recommendations for prospective longitudinal studies, with a large sample size and using standardised BPS instruments and definitions. The following topics for future research were most often recommended, including intervention and treatment, mechanisms and underlying causes of BPS and the prevalence, incidence and persistence of BPS. Many reviews reported that comparison of results was limited due to heterogeneity of the included studies.

Overview of the recommendations and limitations reported by the included reviews. In total, 36 reviews were included in the review of reviews. Only recommendations and limitations reported by three or more reviews are included in the figures. Reviews that make multiple recommendations or limitations may be included more than once.

Gaps

Figure 3 gives an overview of the number of reviews that studied each BPS by the topic of the review. Most of the included reviews focused on individuals with dementia or cognitive impairment studied depression or psychotic symptoms, and they most often studied the prevalence of symptoms. Of the reviews of older populations, almost all studied depressive symptoms and some studied sleep problems or anxiety, whereas the other BPS were not investigated.

Number of reviews that reported on each symptom by the topic of the review. Agg, aggression; Agi, agitation; Anx, anxiety; BPS, behavioural and psychological symptoms; Dep, depressive symptoms; Ela, elation; Psy, psychosis; Sle, sleep problems; Wan, wandering; In total 36 reviews were included in the review of reviews. Reviews that report on multiple topics or more than one BPS are included more than once.

Discussion

Summary of findings

• Prevalence. BPS occur in non-demented, cognitively impaired and demented populations, but there are large variations in reported prevalence estimates.

• Biological associations. Biological factors associated with BPS include health status, homocysteine levels and vascular disease.

• Risk factors. Associations have been found with psychosocial environment and dementia severity. Results are inconsistent, especially for socio-demographic factors, and differ between symptoms.

• Outcomes and care. BPS have been associated with increased burden of care, decreased caregiver's general health and increased caregiver depression scores, but these conclusions come from a limited number of studies. Findings in relation to BPS and institutionalisation, quality of life and disease outcome are generally inconsistent.

Limitations of reviews

Over 97,000 articles have been published on BPS in recent years (up to July 2011). However, in total, only 36 systematic reviews were identified, published from 1989 to 2011, covering 6 to 244 papers, with only 10 reviews, including a meta-analysis. These covered a wide area of research and included studies with large differences in population characteristics, recruitment and definition of BPS. Depressive symptoms were most widely reviewed. Other symptoms, such as apathy, irritability, wandering and elation, are typically ignored, especially in studies of the older population. Aggression, psychosis and wandering have been identified as the BPS that are most difficult to cope with by caregivers [61]. Not all areas of BPS research have yet been adequately reviewed. For example, no review has yet appeared on the neuropathology underpinning BPS, although there are several recent studies on this subject and many possible biological mechanisms may underlie BPS, such as Alzheimer's disease pathology, lower neuronal counts, neurotransmitter changes, genetic risk factors and abnormal neuroendocrinology [62–64]. A high quality systematic review of the biological underpinnings of BPS would give direction to further research, particularly with regard to treatment development.

The quality of the included reviews as measured with the AMSTAR tool was generally low. All except one did not report if the research question and inclusion criteria were established before the conduct of the review, or they did not provide a research question and/or inclusion criteria. Many reviews did not have two independent researchers who selected the studies and extracted the data, or did not report this. None of the reviews reported the potential conflict of interest of the included studies. Furthermore, the inclusion of grey literature and if the search was supplemented by consulting current contents, reviews, textbooks, specialised registers or experts were rarely reported.

Better and more systematic reporting would make it easier to compare the characteristics, results and strengths and limitations of reviews, and the use of reporting checklists, such as PRISMA, is recommended [65]. More details on the populations covered by the review and the characteristics of included studies would be particularly helpful.

Recommendations for future research made by the reviews were variable, with many recommendations made only by one or two reviews. Only more general recommendations were made by several reviews. This has been previously reported by Clark et al., who examined 2,535 Cochrane reviews and found that the characterisation of the needs for future research was less than explicit [66]. In addition, it has been previously found that reviews tend to be too optimistic when drawing conclusions from their results [67, 68]. It has been recommended that research gaps should be identified more systematically, rating the reasons of research gaps in terms of population, intervention, comparison, outcome and setting (PICOS), including insufficient information, biased information, inconsistency or not the right information [69], although this tool has been designed for reviews of intervention studies and may not be suitable for reviews of observational studies.

Limitations of original studies

The reviews have included individual research studies with a large degree of heterogeneity in study design (for example, definition and measurement of BSP, level of cognitive impairment, population characteristics and recruitment of participants), making cross study comparisons difficult. Many different instruments are used to measure BPS, including the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) [70], CERAD-BRSD [71] and the Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer's Disease scale (BEHAVE-AD) [72]. Symptom-specific instruments are also used, including the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) for depressive symptoms [73]. Some instruments use self-ratings (for example, GDS), while others are based on a caregiver interview (for example, NPI). Across instruments there is no consistency in the definition and severity of the symptoms.

Some studies focused on the general older population, while others selected only those with dementia or MCI. Even within impaired groups large differences exist in the measurement of cognitive function. Some study populations were divided by cognitive status (for example, normal, mild or other cognitive impairment and dementia) using diagnostic criteria applied independently of BPS. It may be that the phenotypes of BPS (for example, the causes of depression or agitation) have a different basis at different stages of cognitive impairment and, therefore, studies using different groups will have discrepant findings. Other features, such as the age and gender of participants, and the setting where they were recruited, also vary. If samples are not representative of the population (either that of older people in the community or people with dementia) conclusions may be difficult to generalise.

Limitations of our review of review

There is no Mesh or Emtree search term for BPS, so search terms for individual symptoms and text searches had to be combined. As many different terms are used to describe BPS, it is possible that we may have missed relevant reviews, though we have checked all reference lists of relevant papers. One author undertook data selection and extraction.

Many different definitions of BPS have been used in the literature. Here we used symptom definitions as used by the most commonly used instruments to measure BPS, including the NPI. However, symptom definitions may overlap and there was heterogeneity in symptom definitions that were used by the reviews. Depression is especially problematic. All of the reviews included here that studied depression included studies investigating major depression as well as studies investigating depressive symptoms. In the original studies, decisions about depression can be made at recruitment, when applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria or during measurement at baseline and follow-up. In some studies, only people with or without depressive symptoms or major depression are recruited, or participants with major depression can be excluded from the study at the participant selection stage. At the data collection stage, the definition of depression can include both major depression and minor depression using a cut-off score (for example, a CES-D score higher than 16); it can include both depressive symptoms and major depression separately (for example, DSM definitions for major and minor depression or CES-D scores 16 to 20 and CES-D higher than 20), or either depressive symptoms only (for example, using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory to measure depressive symptoms in the context of BPSD) or major depression only (for example, DSM definition for major depression).

By reviewing reviews and not the original studies, it is likely that noise has been introduced. Furthermore, with the diverse and generally qualitative outcomes of the majority of reviews, we were unable to combine results quantitatively and, therefore, a meta-meta-analysis was not possible.

Recommendations for future research

Recommendations for future reviews on BPS:

• More reviews on BPS are needed, for example, on neuropathological associations

• Improve the quality of reporting of reviews

• Choose reviews that include all BPS not just symptoms of depression/psychosis

• Clearer reporting, using a checklist tool, for example, PRISMA

• Clearer and more specific recommendations for future research, for example, PICOS if applicable

Recommendations for original research on BPS:

• Prospective longitudinal studies

• Large sample size

• Standardised instruments for BPS

• Wide age range, including oldest old

• Improved comparability of results; report study characteristics clearly

Conclusions

No clear conclusions could be made on the prevalence, biology, risk factors and outcomes of BPS. However, by pulling together this wide variety of research, we have been able to give an overview of the recommendations, limitations and gaps of current research in BPS that may inform future research. More high quality reviews including all BPS, not just depressive symptoms, are needed. Future original research should include longitudinal studies with larger sample sizes to further assess the complex relations between BPS, cognitive function and psychological, social and biological factors. One of the main questions raised by the reviews is how best to define and measure BPS within and across populations (that is, different levels of cognitive function, population vs. clinical based). A wider use of the most frequently cited instruments to measure BPS, such as the NPI, would improve comparability. Studies should report clearly the characteristics of their population, the inclusion and exclusion criteria that were used and how they defined BPS, particularly depression. A better understanding of BPS, including their definition, evaluation, underlying mechanisms, risk factors, prevalence and progression will have important implications for prevention and treatment. This has the potential to significantly improve quality of life in people with dementia and their carers as well has having other positive impacts, for example, on economics, institutionalisation and worsening of both cognitive and non-cognitive symptoms.

Abbreviations

- AMSTAR:

-

a measurement tool for the 'assessment of multiple systematic reviews'

- APOE E:

-

Apolipoprotein E

- BEHAVE-AD:

-

Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer's Disease scale

- BPS:

-

behavioural and psychological Symptoms

- BPSD:

-

behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia

- BSRS:

-

Brief Behaviour Symptom Rating Scale

- CERAD-BRSD:

-

Behavior Rating Scale for Dementia of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease

- CES-D:

-

Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale

- COMT:

-

Catechol-O-methyltransferase

- DSM:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- GDS:

-

Geriatric Depression Scale

- MAO-A:

-

Mono-amine oxidase A

- MCI:

-

Mild cognitive impairment

- NPI:

-

Neuropsychiatric Inventory

- PICOS:

-

population, intervention, comparison, outcome and setting

- PRISMA:

-

Cochrane Collaboration and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

References

Savva GM, Zaccai J, Matthews FE, Davidson JE, McKeith I, Brayne C: Prevalence, correlates and course of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia in the population. Br J Psychiatry. 2009, 194: 212-219. 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.049619.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Dementia - Supporting people with Dementia and their Carers in Health and Social Care. 2006

Department of Health (UK): Living Well with Dementia: A National Dementia Strategy. 2009

Smith V, Devane D, Begley CM, Clarke M: Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011, 11: 15-10.1186/1471-2288-11-15.

Kraepelin E: Psychiatrie: ein Lehrbuch für studierende und Ärtze. 1896, Leipzig: J.A. Barth

Roth M: The natural history of mental disorder in old age. J Ment Sci. 1955, 101: 281-301.

Finkel SI, Costa e Silva J, Cohen G, Miller S, Sartorius N: Behavioral and psychological signs and symptoms of dementia: a consensus statement on current knowledge and implications for research and treatment. Int Psychogeriatr. 1996, 8 (Suppl 3): 497-500.

Alzheimer A: Über einen eigenartigen schweren Er Krankungsprozeb der Himrinde. Neurol Zbl. 1906, 23: 1129-1136.

Reisberg B, Borenstein J, Salob SP, Ferris SH, Franssen E, Georgotas A: Behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer's disease: phenomenology and treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987, 48 Suppl: 9-15.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Open Med. 2009, 3: e123-e130. 10.2174/1874306400903010123.

Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers M, Andersson N, Hamel C, Porter AC, Tugwell P, Moher D, Bouter LM: Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007, 15: 7-10.

Shea BJ, Hamel C, Wells GA, Bouter LM, Kristjansson E, Grimshaw J, Henry DA, Boers M: AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009, 62: 1013-1020. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.009.

Cole MG, Bellavance F: The prognosis of depression in old age. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997, 5: 4-14.

Christensen H, Griffiths K, Mackinnon A, Jacomb P: A quantitative review of cognitive deficits in depression and Alzheimer-type dementia. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1997, 3: 631-651.

Cole MG, Bellavance F: Depression in elderly medical inpatients: a meta-analysis of outcomes. Can Med Assoc J. 1997, 157: 1055-1060.

Cole MG: Does depression in older medical inpatients predict mortality? A systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007, 29: 425-430. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.07.002.

Henry JD, Crawford JR: A meta-analytic review of verbal fluency deficits in depression. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2005, 27: 78-101. 10.1080/138033990513654.

Nakajima GA, Wenger NS: Quality indicators for the care of depression in vulnerable elders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007, 55: S302-S311.

Savoie I, Morettin D, Green CJ, Kazanjian A: Systematic review of the role of gender as a health determinant of hospitalization for depression. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2004, 20: 115-127.

Chen R, Copeland JR, Wei L: A meta-analysis of epidemiological studies in depression of older people in The People's Republic of China. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999, 14: 821-830. 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199910)14:10<821::AID-GPS21>3.0.CO;2-0.

Monastero R, Mangialasche F, Camarda C, Ercolani S, Camarda R: A systematic review of neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimer's Dis. 2009, 18: 11-30.

Apostolova LG, Cummings JL: Neuropsychiatric manifestations in mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review of the literature. Dementia Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008, 25: 115-126. 10.1159/000112509.

Seitz D, Purandare N, Conn D: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among older adults in long-term care homes: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010, 22: 1025-1039. 10.1017/S1041610210000608.

Zuidema S, Koopmans R, Verhey F: Prevalence and predictors of neuropsychiatric symptoms in cognitively impaired nursing home patients. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2007, 20: 41-49. 10.1177/0891988706292762.

Shub D, Ball V, Abbas AAA, Gottumukkala A, Kunik ME: The link between psychosis and aggression in persons with dementia: a systematic review. Psychiatr Q. 2010, 81: 97-110. 10.1007/s11126-009-9121-7.

Wragg RE, Jeste DV: Overview of depression and psychosis in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1989, 146: 577-587.

Ropacki SA, Jeste DV: Epidemiology of and risk factors for psychosis of Alzheimer's disease: a review of 55 studies published from 1990 to 2003. Am J Psychiatry. 2005, 162: 2022-2030. 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2022.

Luppa M, Sikorski C, Luck T, Ehreke L, Konnopka A, Wiese B, Weyerer S, Konig HH, Riedel-Heller SG: Age- and gender-specific prevalence of depression in latest-life - Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affective Disord. 2012, 136: 212-221. 10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.033.

Beekman AT, Copeland JR, Prince MJ: Review of community prevalence of depression in later life. Br J Psychiatry. 1999, 174: 307-311. 10.1192/bjp.174.4.307.

Meeks TW, Vahia IV, Lavretsky H, Kulkarni G, Jeste DV: A tune in "a minor" can "b major": a review of epidemiology, illness course, and public health implications of subthreshold depression in older adults. J Affective Disord. 2011, 129: 126-142. 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.015.

Djernes JK: Prevalence and predictors of depression in populations of elderly: a review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006, 113: 372-387. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00770.x.

Alwahhabi F: Anxiety symptoms and generalized anxiety disorder in the elderly: a review. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2003, 11: 180-193. 10.1080/10673220303944.

Jorm AF, van Duijn CM, Chandra V, Fratiglioni L, Graves AB, Heyman A, Kokmen E, Kondo K, Mortimer JA, Rocca WA: Psychiatric history and related exposures as risk factors for Alzheimer's disease: a collaborative re-analysis of case-control studies. Int J Epidemiol. 1991, 20 (Suppl 2): S43-S47.

Verkaik R, Nuyen J, Schellevis F, Francke A: The relationship between severity of Alzheimer's disease and prevalence of comorbid depressive symtoms and depression: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007, 22: 1063-1086. 10.1002/gps.1809.

Huang CQ, Wang ZR, Li YH, Xie YZ, Liu QX: Cognitive function and risk for depression in old age: a meta-analysis of published literature. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011, 23: 516-525. 10.1017/S1041610210000049.

Jorm AF: History of depression as a risk factor for dementia: an updated review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001, 35: 776-781. 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00967.x.

Jorm AF: Is depression a risk factor for dementia or cognitive decline? A review. Gerontology. 2000, 46: 219-227. 10.1159/000022163.

Ohayon MM, Carskadon MA, Guilleminault C, Vitiello MV: Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan. Sleep. 2004, 27: 1255-1273.

Floyd JA, Janisse JJ, Jenuwine ES, Ager JW: Changes in REM-sleep percentage over the adult lifespan. Sleep. 2007, 30: 829-836.

Floyd JA, Medler SM, Ager JW, Janisse JJ: Age-related changes in initiation and maintenance of sleep: a meta-analysis. Res Nurs Health. 2000, 23: 106-117. 10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(200004)23:2<106::AID-NUR3>3.0.CO;2-A.

Kuo HK, Sorond FA, Chen JH, Hashmi A, Milberg WP, Lipsitz LA: The role of homocysteine in multisystem age-related problems: A systematic review. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005, 60: 1190-1201. 10.1093/gerona/60.9.1190.

Flirski M, Sobow T, Kloszewska I: Behavioural genetics of Alzheimer's disease: A comprehensive review. Arch Med Sci. 2011, 7: 195-210.

Huang CQ, Dong BR, Lu ZC, Yue JR, Liu QX: Chronic diseases and risk for depression in old age: a meta-analysis of published literature. Ageing Res Rev. 2010, 9: 131-141. 10.1016/j.arr.2009.05.005.

Chang-Quan H, Xue-Mei Z, Bi-Rong D, Zhen-Chan L, Ji-Rong Y, Qing-Xiu L: Health status and risk for depression among the elderly: a meta-analysis of published literature. Age Ageing. 2010, 39: 23-30. 10.1093/ageing/afp187.

Almeida OP, McCaul K, Hankey GJ, Norman P, Jamrozik K, Flicker L: Homocysteine and depression in later life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008, 65: 1286-1294. 10.1001/archpsyc.65.11.1286.

Stetler C, Miller GE: Depression and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activation: A quantitative summary of four decades of research. Psychosom Med. 2011, 73: 114-126. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31820ad12b.

Kuo HK, Yen CJ, Chang CH, Kuo CK, Chen JH, Sorond F: Relation of C-reactive protein to stroke, cognitive disorders, and depression in the general population: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2005, 4: 371-380. 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70099-5.

Camus V, Kraehenbuhl H, Preisig M, Bula CJ, Waeber G: Geriatric depression and vascular diseases: what are the links?. J Affective Disord. 2004, 81: 1-16. 10.1016/j.jad.2003.08.003.

Vink D, Aartsen MJ, Schoevers RA: Risk factors for anxiety and depression in the elderly: a review. J Affective Disord. 2008, 106: 29-44. 10.1016/j.jad.2007.06.005.

Cole MG, Dendukuri N: Risk factors for depression among elderly community subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2003, 160: 1147-1156. 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1147.

Gaugler JE, Yu F, Krichbaum K, Wyman JF: Predictors of nursing home admission for persons with dementia. Med Care. 2009, 47: 191-198. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818457ce.

Black W, Almeida OP: A systematic review of the association between the Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia and burden of care. Int Psychogeriatr. 2004, 16: 295-315. 10.1017/S1041610204000468.

Banerjee S, Samsi K, Petrie CD, Alvir J, Treglia M, Schwam EM, de Valle M: What do we know about quality of life in dementia? A review of the emerging evidence on the predictive and explanatory value of disease specific measures of health related quality of life in people with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009, 24: 15-24. 10.1002/gps.2090.

Lee M, Chodosh J: Dementia and life expectancy: what do we know?. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009, 10: 466-471. 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.03.014.

Fischer CE, Verhoeff NP, Churchill K, Schweizer TA: Functional outcome in delusional Alzheimer disease patients: a systematic review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009, 27: 105-110. 10.1159/000194659.

Luppa M, Sikorski C, Luck T, Ehreke L, Konnopka A, Wiese B, Weyerer S, Konig HH, Riedel-Heller SG: Age- and gender-specific prevalence of depression in latest-life--systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2012, 136: 212-221. 10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.033.

Chang-Quan H, Xue-Mei Z, Bi-Rong D, Zhen-Chan L, Ji-Rong Y, Qing-Xiu L: Health status and risk for depression among the elderly: a meta-analysis of published literature. Age Ageing. 2010, 39: 23-30. 10.1093/ageing/afp187.

Beekman AT, Copeland JR, Prince MJ: Review of community prevalence of depression in later life. Br J Psychiatry. 1999, 174: 307-311. 10.1192/bjp.174.4.307.

Ropacki SA, Jeste DV: Epidemiology of and risk factors for psychosis of Alzheimer's disease: a review of 55 studies published from 1990 to 2003. Am J Psychiatry. 2005, 162: 2022-2030. 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2022.

Ownby RL, Crocco E, Acevedo A, John V, Loewenstein D: Depression and risk for Alzheimer disease: systematic review, meta-analysis, and metaregression analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006, 63: 530-538. 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.530.

International Psychogeriatric Association (IPA): Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD) Educational Pack. 2002

Serra L, Perri R, Cercignani M, Spano B, Fadda L, Marra C, Carlesimo GA, Caltagirone C, Bozzali M: Are the behavioral symptoms of Alzheimer's disease directly associated with neurodegeneration?. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010, 21: 627-639.

Berlow YA, Wells WM, Ellison JM, Sung YH, Renshaw PF, Harper DG: Neuropsychiatric correlates of white matter hyperintensities in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010, 25: 780-788.

Staekenborg SS, Gillissen F, Romkes R, Pijnenburg YA, Barkhof F, Scheltens P, van der Flier WM: Behavioural and psychological symptoms are not related to white matter hyperintensities and medial temporal lobe atrophy in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008, 23: 387-392. 10.1002/gps.1891.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. Open Med. 2009, 3: e123-e130. 10.2174/1874306400903010123.

Clarke L, Clarke M, Clarke T: How useful are Cochrane reviews in identifying research needs?. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2007, 12: 101-103. 10.1258/135581907780279648.

Olsen O, Middleton P, Ezzo J, Gotzsche PC, Hadhazy V, Herxheimer A, Kleijnen J, McIntosh H: Quality of Cochrane reviews: assessment of sample from 1998. BMJ. 2001, 323: 829-832. 10.1136/bmj.323.7317.829.

Schunemann H, Oxman A, Vist G, Higgins J, Deeks J, Glasziou P, Guyatt G: Chapter 12: Interpreting results and drawing conclusions. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Version 5.1.0). Edited by: Higgins J, Green S. 2011, Oxford: The Cochrane Collaboration, 359-388.

Robinson KA, Saldanha IJ, McKoy NA: Development of a framework to identify research gaps from systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011, 64: 1325-1330. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.06.009.

Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J: The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994, 44: 2308-2314. 10.1212/WNL.44.12.2308.

Tariot PN: CERAD behavior rating scale for dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 1996, 8 (Suppl 3): 317-320.

Reisberg B, Auer SR, Monteiro IM: Behavioral pathology in Alzheimer's disease (BEHAVE-AD) rating scale. Int Psychogeriatr. 1996, 8 (Suppl 3): 301-308.

Yesavage JA: Geriatric Depression Scale. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988, 24: 709-711.

Acknowledgements

RvdL receives a studentship from National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) for Cambridgeshire and Peterborough. The funding body had no role in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

RvdL participated in the conception and design of the study, performed the literature search, interpreted and summarised the data, and drafted the manuscript. BS and GS participated in interpretation of the data and critically revised the manuscript. TD and CB participated in the conception and design of the study, interpretation and visualisation of the results and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

13195_2012_105_MOESM1_ESM.DOCX

Additional file 1: Search terms (Embase and Medline, 29 March 2012). An overview of the search terms that were used. (DOCX 22 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

van der Linde, R.M., Stephan, B.C., Savva, G.M. et al. Systematic reviews on behavioural and psychological symptoms in the older or demented population. Alz Res Therapy 4, 28 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/alzrt131

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/alzrt131