Abstract

Background

This meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the postoperative clinical outcomes and safety of the direct anterior approach (DAA) versus posterior approach (PA) in total hip arthroplasty (THA).

Methods

We searched PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, the Cochrane Library, and Google databases from inception to June 2018 to select studies that compared the DAA and PA for THA. Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included. Outcomes included Harris hip score at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 1 year; VAS at 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h; incision length, operation time, postoperative blood loss, length of hospital stay, and complications (intraoperative fracture, postoperative dislocation, heterotopic ossification (HO), and groin pain).

Results

Nine RCTs totaling 754 THAs (DAA group = 377, PA group = 377) met the criteria to be included in this meta-analysis. The present meta-analysis indicated that, compared with PA group, DAA group was associated with an increase of the Harris hip score at the 2-week and 4-week time points. No significant difference was found between DAA and PA groups of the Harris hip scores at 12 weeks, 1 year length of hospital stay (p > 0.05). DAA group was associated with a reduction of the VAS at 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h with statistical significance (p < 0.05). What is more, DAA was associated with a reduction of the incision length and postoperative blood loss (p < 0.05). There was no significant difference between the operation time and complications (intraoperative fracture, postoperative dislocation, HO, and groin pain).

Conclusion

In THA patients, compared with PA, DAA was associated with an early functional recovery and less pain scores. What is more, DAA was associated with shorter incision length and blood loss.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is an effective surgery alternative for patients with hip osteoarthritis (OA) or femoral head necrosis [1, 2]. Kurtz et al. [3] reported a 50% increase in the prevalence of THA from 1990 to 2002 and estimated nearly 572,000 THAs in 2030. Most THA patients experience pain relief, improved function, and restoration of quality of life [4]. However, nearly 7–15% patients were dissatisfied with THA due to the postoperative pain and functional recovery [5, 6]. The potential causes of postoperative pain include failure of fixation and damage of soft tissues [7]. Among the causes of damage of soft tissues, surgical approach was one of the influential factors [8, 9]. Choosing the optimal surgical approach could minimize pain severity, improve hip function, and thus increase patients’ satisfaction.

Currently, there are two common surgical approaches; direct anterior approach (DAA) and posterior approach (PA) are utilized in THA’s [10, 11]. Several reports have shown that the DAA was superior to the PA in terms of the postoperative blood loss and faster rehabilitation. The reason may be that DAA results in less soft tissue damage due to the fact that DAA relies on an intermuscular plane for insertion of the components [9]. For the above reasons, DAA has gained popularity in recent years [12]. However, some studies reported that DAA has more complications (femoral neck fracture, femoral perforation) than other approaches. Additionally, the learning curve of DAA has been reported to be relatively longer than other approaches [13, 14]. Two relevant meta-analyses [11, 15] that compare DAA with other approaches were published. However, shortcoming of these two meta-analyses should be noted. Higgins et al. [11] included retrospective studies and found that there was no significant difference between DAA and PA groups in the functional outcomes. Miller et al. [15] conducted a meta-analysis that compares DAA and PA for THA patients. However, they mixed the different follow-up outcomes for analysis and thus the heterogeneity was large. Another limitation was that they also included retrospective studies and thus selection bias could not be avoided.

Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis based only on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to compare the clinical outcomes of DAA versus PA in THA. We hypothesized that DAA is superior to PA in terms of the clinical outcomes in THA.

Methods

This systematic review fully adhered to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [16].

Search strategy

We manually searched PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, the Cochrane Library, and Google databases from inception to June 2018. There was no language restriction for all of the publications. The search terms included key words and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms related to ““Arthroplasty, Replacement, Hip”[Mesh]”; total hip arthroplasty; total hip replacement; THA, THR, direct anterior approach, DAA, posterior approach, and PA. The reference lists of included studies or meta-analysis were also manually examined for potential missing records. This meta-analysis did not involve direct contact with individual patients; therefore, no ethics approval was needed.

Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria

-

(1)

Participants: patients prepared for THA.

-

(2)

Interventions: the intervention group received the DAA for THA.

-

(3)

Comparisons: the control group received PA for THA.

-

(4)

Outcomes: Harris hip score at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 1 year; VAS at 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h; incision length, operation time, postoperative blood loss, length of hospital stay, and complications (intraoperative fracture, postoperative dislocation, heterotopic ossification (HO), and groin pain).

-

(5)

Study design: RCTs were regarded as eligible in the study.

Non-RCTs, letters, and editorial comments were excluded in this meta-analysis.

Study selection

According to the formulated search strategy, all papers were guided into Endnote X7 (Thompson Reuters, CA, USA). Two reviewers (Zhao Wang and Hong-wei Bao) independently scanned the titles and abstracts of the potential studies. If there was a controversy between the reviewers, we asked a senior reviewer to make a decision.

Date extraction

Two reviewers (Zhao Wang and Jing-zhao Hou) independently extract the following information: first author name and publication year, country, patients’ general characteristic (no. of patients, age, proportion of female patients, BMI), outcomes, study, and follow-up duration. The primary outcomes were Harris hip score at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 12 weeks and 1 year, VAS at 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h; incision length, operation time, postoperative blood loss, length of hospital stay, and complications (intraoperative fracture, postoperative dislocation, heterotopic ossification (HO), and groin pain).

Outcome measures and statistical analysis

Continuous outcomes (Harris hip score at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 1 year; VAS at 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h; incision length, operation time, postoperative blood loss, and length of hospital stay) were expressed as the weighted mean differences (WMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Complications (intraoperative fracture, postoperative dislocation, HO, and groin pain) were expressed as risk ratio (RR) with 95% CIs. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant difference. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata software, version 12.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA). To assess the heterogeneity, the I2 index and corresponding p value were calculated. When I2 was less than 50%, there was low heterogeneity; otherwise, there was a high heterogeneity. Publication bias was visually assessed using funnel plots (effect size was symmetry = no publication bias) and was quantitatively assessed using Begg’s test (p > 0.05 = no publication bias).

Results

Search results and general characteristic

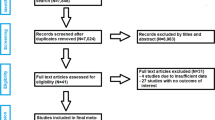

Figure 1 shows the flowchart for selection of studies. First, a total of 285 studies were identified from the electronic databases (PubMed = 147, Embase = 56, Web of Science = 23, Cochrane Library = 19, Google database = 30). Then, all papers were input into Endnote X7 (Thomson Reuters Corp., USA) software for the removal of duplicate papers. A total of 151 papers were reviewed, and 142 papers were removed according to the inclusion criteria at abstract and title levels. Additionally, one study was a duplicate publication so we only included the most recently published paper. Ultimately, 9 clinical studies with 754 patients (DAA group = 377, PA group = 377) were involved in the meta-analysis [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. The general characteristic of the included studies can be seen in Table 1. Publication years ranged from 2006 to 2018. Number of patients ranged from 27 to 60, and mean age ranged from 59 to 65. Follow-up duration ranged from 1 month to 1 year.

Quality assessment

The risk of bias graph and risk of bias summary is summarized in Figs. 2 and 3 respectively. Random sequence generation procedure (selection bias) was low and unclear in two and five of the included studies respectively. Allocation concealment was low in four studies and high in two studies. Blinding of participant was with high risk of bias in all of the included studies. Attrition bias was unclear in six studies. Other bias was high in one study and two were with unclear risk of bias, the rest were all with low risk of bias.

Results of meta-analysis

Harris hip score at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 1 year

Data on 661 primary THAs (including 329 with DAA and 322 with PA) were pooled from 5 trials analyzing the Harris hip score at 2 weeks. The DAA group was associated with an increase of the Harris hip at 2 weeks and 6 weeks (2 weeks, WMD = 7.41, 95%CI 4.91 to 9.92, p = 0.000; Fig. 4; 6 weeks, WMD = 6.80, 95%CI 0.64 to 12.95, p = 0.030, Fig. 5). The DAA and PA groups were not statistically significantly different with regard to pain at 12 weeks and 1 year (12 weeks, WMD = 2.56, 95%CI − 0.40 to 5.51, p = 0.090, Fig. 6; 1 year, WMD = 0.36, 95%CI − 1.51 to 2.23, p = 0.709, Fig. 7).

VAS at 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h

Compared with PA group, the DAA group was associated with a decrease of the VAS at each time point (24 h, WMD = − 0.71, 95%CI − 0.90 to − 0.51, p = 0.000; 48 h, WMD = − 1.55, 95%CI − 2.24 to − 0.86, p = 0.000; 72 h, WMD = − 1.56, 95%CI − 2.64 to − 0.48, p = 0.005, Fig. 8).

Incision length

Data on 359 primary THAs (including 184 with DAA and 175 with PA) were pooled from 4 trials analyzing the incision length. Compared with PA, DAA group was associated with a reduction of the incision length by 3.51 cm (WMD = − 3.51, 95%CI − 4.15 to − 2.86, p = 0.000, Fig. 9).

Operation time

Data on 446 primary THAs (including 227 with DAA and 219 with PA) were pooled from 5 trials analyzing the operation time. Compared with PA, DAA group was not associated with an increase of the operation time (WMD = 3.83, 95%CI − 14.39 to 22.06, p = 0.680, Fig. 10).

Postoperative blood loss

Data on 380 primary THAs (including 184 with DAA and 196 with PA) were pooled from 4 trials analyzing the postoperative blood loss. Compared with PA, DAA group was associated with a reduction of the postoperative blood loss (WMD = − 67.02, 95%CI − 131.46 to − 2.58, p = 0.041, Fig. 11).

Length of hospital stay

Four studies totaling 290 THAs (DAA = 152, PA = 138) analyzing the length of hospital stay. There was no significant difference between the DAA group and PA group in terms of the length of hospital stay (WMD = − 0.26, 95%CI − 0.58 to 0.06, p = 0.118, Fig. 12).

Complications

There was no significant difference between DAA group and PA group in terms of the intraoperative fracture (RR = 1.62, 95%CI 1.62 to 4.46, p = 0.350, Fig. 13); postoperative dislocation (RR = 0.52, 95%CI 0.10 to 2.27, p = 0.441, Fig. 13), HO (RR = 1.57, 95%CI 0.49 to 5.09, p = 0.450, Fig. 13), and groin pain (RR = 2.62, 95%CI 0.63 to 10.94, p = 0.191, Fig. 13).

Discussion

Main findings

Our meta-analysis indicated that DAA has a positive role in reducing acute pain intensity, improving postoperative rehabilitation, and decreasing the length of incision and blood loss. We used sensitivity analysis to further confirm the reliability of our conclusion. Most of our analyses were low- to middle-quality evidence.

New knowledge of this meta-analysis

A major strength of our current meta-analysis is that we limited the inclusion criteria to RCTs. Another new knowledge of this meta-analysis is that we performed a comprehensive analysis (postoperative hip function at same duration follow-up, postoperative pain intensity, blood loss, length of incision, and the length of hospital stay). As far as we know, this meta-analysis is the most comprehensive one to date to compare DAA versus PA for THA.

Implications for clinical practice

We found statistically significant differences between DAA and PA with regards to Harris hip score at 2 weeks and 4 weeks post op. Putananon et al. [26] performed a network meta-analysis that compares DAA, lateral, PA, and posterior approaches in THA. Those results showed that DAA for THA gave the best postoperative VAS and Harris hip score. However, they only compared the VAS and Harris hip scores at final follow-up. In our current meta-analysis, we categorized the VAS and Harris hip score at multiple time intervals post-operatively. Our results showed that DAA was superior to PA in terms of the Harris hip score at 2 weeks and 6 weeks. There was no significant difference between the DAA and PA groups in terms of the Harris hip score at 12 weeks and 1 year follow-up. Zhao et al. [24] found that DAA group was associated with a better functional recovery than PA group at 3 months. However, there was no significant difference between DAA and PA groups at 6 month follow-up.

We also found that the DAA group was associated with a reduction of pain intensity at 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h compared to the PA group. One possible rationale for improving Harris hip score and decreasing pain intensity was the avoidance of muscle splitting and reduced soft tissue damage in DAA group than that of PA group. We found two RCTs that use C-reactive protein (CRP) level to support our hypothesis [24]. Zhao et al. [24] found that, for postoperative day 1 to 4, the level of CRP, IL-6, and ESR was significantly lower in DAA group than that in PA group.

We compared four complications (intraoperative fracture, postoperative dislocation, HO, and groin pain) between DAA group and PA group. Results showed that there was no significant difference between these complications (p > 0.05). Theoretically speaking, DAA has also been suggested to have an advantage in terms of dislocation risk over PA THA. Current meta-analysis found no significant difference between DAA and PA groups in terms of the postoperative dislocation. Two studies [20, 24] initiated after performance of 150 or 100 THAs via the direct anterior approach and thus could minimize the influence of a learning curve. The revision rate and risk of revision was comparable in DAA group and PA group in THA [27].

Several limitations in this meta-analysis should be noted. First, the follow-up duration of VAS was relatively short, and long-term follow-up is necessary to identify the long-term effects of DAA. Second, learning curve of the DAA and PA were not reported in the included studies and thus we cannot comment on the learning curve regarding either approach. Third, postoperative rehabilitation program was different and thus may cause heterogeneity for the final outcome. Lastly, the blinding of the participant was high in all of the studies, and this high bias affects the final outcomes.

Conclusion

In THA patients, compared with PA, DAA was associated with an early functional recovery and lower pain scores. What’s more, DAA was associated with shorter incision length and blood loss. There was no significant difference in complication rated between the DAA and PA groups. Considering the limitation of this meta-analysis, more high quality RCTs are needed to further identify the effects of DAA in THA patients.

Abbreviations

- CIs:

-

Confidence intervals

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- DAA:

-

Direct anterior approach

- HO:

-

Heterotopic ossification

- MeSH:

-

Medical Subject Headings

- OA:

-

Osteoarthritis

- PA:

-

Posterior approach

- PRISMA:

-

preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- RR:

-

Risk ratio

- THA:

-

Total hip arthroplasty

- WMD:

-

Weighted mean difference

References

Chen X, Xiong J, Wang P, et al. Robotic-assisted compared with conventional total hip arthroplasty: systematic review and meta-analysis. Postgrad Med J. 2018;94:335–41.

Yang Q, Zhang Z, Xin W, Li A. Preoperative intravenous glucocorticoids can decrease acute pain and postoperative nausea and vomiting after total hip arthroplasty: a PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e8804.

Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:780–5.

Zhao Z, Ma X, Ma J, Sun X, Li F, Lv J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the topical administration of fibrin sealant in total hip arthroplasty. Sci Rep. 2018;8:78.

Anakwe RE, Jenkins PJ, Moran M. Predicting dissatisfaction after total hip arthroplasty: a study of 850 patients. J Arthroplast. 2011;26:209–13.

Jones CA, Beaupre LA, Johnston DW, Suarez-Almazor ME. Total joint arthroplasties: current concepts of patient outcomes after surgery. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 2007;33:71–86.

Zomar BO, Bryant D, Hunter S, Howard JL, Vasarhelyi EM, Lanting BA. A randomised trial comparing spatio-temporal gait parameters after total hip arthroplasty between the direct anterior and direct lateral surgical approaches. Hip Int. 2018; https://doi.org/10.1177/1120700018760262.

Sutphen SA, Berend KR, Morris MJ, Lombardi AV Jr. Direct anterior approach has lower deep infection frequency than less invasive direct lateral approach in primary total hip arthroplasty. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2018;27:21–4.

Graves SC, Dropkin BM, Keeney BJ, Lurie JD, Tomek IM. Does surgical approach affect patient-reported function after primary THA? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:971–81.

Bernard J, Razanabola F, Beldame J, et al. Electromyographic study of hip muscles involved in total hip arthroplasty: surprising results using the direct anterior minimally invasive approach. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2018. [Epub ahead of print].

Higgins BT, Barlow DR, Heagerty NE, Lin TJ. Anterior vs. posterior approach for total hip arthroplasty, a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Arthroplast. 2015;30:419–34.

Post ZD, Orozco F, Diaz-Ledezma C, Hozack WJ, Ong A. Direct anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty: indications, technique, and results. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22:595–603.

Stone A, Sibia U, Atkinson R, Turner T, King P. Evaluation of the learning curve when transitioning from posterolateral to direct anterior hip arthroplasty: a consecutive series of 1000 cases. J Arthroplast. 2018; [epub ahead of print]

Ponzio D, Poultsides L, Salvatore A, Lee Y, Memtsoudis S, Alexiades M. In-hospital morbidity and postoperative revisions after direct anterior vs posterior total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2018;33:1421–5.

Miller LE, Gondusky JS, Bhattacharyya S, Kamath AF, Boettner F, Wright J. Does surgical approach affect outcomes in total hip arthroplasty through 90 days of follow-up? A systematic review with meta-analysis. J Arthroplast. 2018;33:1296–302.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

Barrett WP, Turner SE, Leopold JP. Prospective randomized study of direct anterior vs postero-lateral approach for total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2013;28:1634–8.

Bergin PF, Doppelt JD, Kephart CJ, et al. Comparison of minimally invasive direct anterior versus posterior total hip arthroplasty based on inflammation and muscle damage markers. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:1392–8.

Christensen CP, Jacobs CA. Comparison of patient function during the first six weeks after direct anterior or posterior total hip arthroplasty (THA): a randomized study. J Arthroplast. 2015;30:94–7.

Rodriguez JA, Deshmukh AJ, Rathod PA, et al. Does the direct anterior approach in THA offer faster rehabilitation and comparable safety to the posterior approach? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:455–63.

Taunton MJ, Mason JB, Odum SM, Springer BD. Direct anterior total hip arthroplasty yields more rapid voluntary cessation of all walking aids: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Arthroplast. 2014;29:169–72.

Cheng TE, Wallis JA, Taylor NF, et al. A prospective randomized clinical trial in total hip arthroplasty-comparing early results between the direct anterior approach and the posterior approach. J Arthroplast. 2017;32:883–90.

Zhang XL, Wang Q, Jiang Y, Zeng BF. Minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty with anterior incision. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2006;44:512–5.

Zhao HY, Kang PD, Xia YY, Shi XJ, Nie Y, Pei FX. Comparison of early functional recovery after total hip arthroplasty using a direct anterior or posterolateral approach: a randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplast. 2017;32:3421–8.

Zhang Z, Wang C, Yang P, Dang X, Wang K. Comparison of early rehabilitation effects of total hip arthroplasty with direct anterior approach versus posterior approach. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2018;32:329–33.

Putananon C, Tuchinda H, Arirachakaran A, Wongsak S, Narinsorasak T, Kongtharvonskul J. Comparison of direct anterior, lateral, posterior and posterior-2 approaches in total hip arthroplasty: network meta-analysis. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2018;28:255–67.

Mjaaland KE, Svenningsen S, Fenstad AM, Havelin LI, Furnes O, Nordsletten L. Implant survival after minimally invasive anterior or anterolateral vs. conventional posterior or direct lateral approach: an analysis of 21,860 Total hip arthroplasties from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (2008 to 2013). J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99:840–7.

Availability of data and materials

Supporting data is available.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZW designed the study and developed the retrieve strategy. JZH, CHW, and YJZ searched and screened the summaries and titles. XMG, HHW, YXC, XS, HWB, and WF drafted the article. All authors read and approved the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This is a meta-analysis; no relative problems exist.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Hou, Jz., Wu, Ch. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of direct anterior approach versus posterior approach in total hip arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg Res 13, 229 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-018-0929-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-018-0929-4