Abstract

Background

Ethnoveterinary medicine is crucial in many rural areas of the world since people living in remote and marginal areas rely significantly on traditional herbal therapies to treat their domestic animals. In Pakistan, communities residing in remote areas, and especially those still attached to pastoralist traditions, have considerable ethnoveterinary herbal knowledge and they sometimes use this knowledge for treating their animals. The main aim of the study was to review the literature about ethnoveterinary herbals being used in Pakistan in order to articulate potential applications in modern veterinary medicine. Moreover, the review aimed to analyze possible cross-cultural and cross regional differences.

Methods

We considered the ethnobotanical data of Pakistan published in different scientific journals from 2004 to 2018. A total of 35 studies were found on ethnoveterinary herbal medicines in the country. Due to the low number of field studies, we considered all peer-reviewed articles on ethnoveterinary herbal practices in the current review. All the ethnobotanical information included in these studies derived from interviews which were conducted with shepherds/animals breeders as well as healers.

Results

Data from the reviewed studies showed that 474 plant species corresponding to 2386 remedies have been used for treating domestic animals in Pakistan. The majority of these plants belong to Poaceae (41 species) followed by the Asteraceae (32 species) and Fabaceae (29 species) botanical families, thus indicating a possible prevalence of horticultural-driven gathering patterns. Digestive problems were the most commonly treated diseases (25%; 606 remedies used), revealing the preference that locals have for treating mainly minor animal ailments with herbs. The least known veterinary plants recorded in Pakistan were Abutilon theophrasti, Agrostis gigantea, Allardia tomentosa, Aristida adscensionis, Bothriochloa bladhii, Buddleja asiatica, Cocculus hirsutus, Cochlospermum religiosum, Cynanchum viminale, Dactylis glomerata, Debregeasia saeneb, Dichanthium annulatum, Dracocephalum nuristanicum, Flueggea leucopyrus, Launaea nudicaulis, Litsea monopetala, Sibbaldianthe bifurca, Spiraea altaica, and Thalictrum foetidum. More importantly, cross-cultural comparative analysis of Pathan and non-Pathan ethnic communities showed that 28% of the veterinary plants were mentioned by both communities. Cross-regional comparison demonstrated that only 10% of the plant species were used in both mountain and plain areas. Reviewed data confirm therefore that both ecological and cultural factors play a crucial role in shaping traditional plant uses.

Conclusion

The herbal ethnoveterinary heritage of Pakistan is remarkable, possibly because of the pastoral origins of most of its peoples. The integration of the analyzed complex bio-cultural heritage into daily veterinary practices should be urgently fostered by governmental and non-governmental institutions dealing with rural development policies in order to promote the use of local biodiversity for improving animal well-being and possibly the quality of animal food products as well.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ethnoveterinary knowledge (EVK) is a complex body of elements, encompassing concepts, beliefs, practices, skills, and experiences, which are passed vertically or horizontally across generations (mainly orally or via observation of practical skills), concerning animal well-being. This complex body of both knowledge and practices has been and is still fundamental in many rural areas of the globe for assuring the health of livestock and thus the survival of pastoral or agro-pastoral communities [1].

EVK includes many kinds of knowledge and practical skills: ecological knowledge of pastures; ethnoclimatological knowledge of weather forecasting; knowledge of harvesting and/or cultivating and providing animals specific fodder plants that are considered good for their growth and well-being, as well as for increasing the quality of animal-based food products (i.e., dairy products, meat, eggs, honey, and other bee products); recruitment and use of herbal remedies and other natural treatments when animals are ill; ways of managing whole animal breeding systems; and so forth [2].

Ethnoveterinary field studies specifically concerning traditional herbal remedies for treating animal diseases are crucial in many rural areas of the world for several reasons: (a) to propose effective and cheaper treatments alternative and complementary to the use of pharmaceuticals, and especially to decrease the abuse of antibiotics in animal breeding that is in turn detrimental to the quality of animal food products; (b) to foster the sustainable use of local medicinal plant resources in animal care and then to contribute to rural development policies; (c) to promote local bio-cultural heritage; and (d) to investigate the link between human and veterinary plant uses in order to possibly assess the origin of herbal practices [1, 3,4,5,6,7,8,9].

Ethnoveterinary studies are also vital for envisioning new equilibria between ecosystem “health” and animal and human health systems, to respect and honor non-Western, traditional, orally transmitted, herbal practices devoted to animals, and especially to encourage trans-disciplinary applied research in the field of animal health care (i.e., biomedical potential of ethnoveterinary practices and ingredients, socio-economic and cost effectiveness of herbal animal treatments, sustainable and sovereign rural development policies and strategies based on animal breeding) [10].

Livestock is considered a subsector of agriculture in Pakistan. In the country, the sector contributes 56.3% of the value of agriculture and nearly 11% to the agricultural gross domestic product (AGDP). In this sector, milk is the single most important commodity and the country is ranked fourth in milk production worldwide after China, India, and the USA [11]. This sector plays an important role in poverty reduction strategies, and it may be developed very quickly. It requires macroeconomic preferences for the economy of Pakistan and the vigorous development of rural economic growth [12]. According to a governmental economic survey of Pakistan [13], the national herd includes 29.6 million cows, 27.3 million buffalo, 53.8 million goats, 26.5 million sheep, and 0.9 million camels. Yet, over the past three decades, the livestock sector which in Pakistan employs more than 35 million people has only experienced an average growth of 2.9%, which is insufficient production for the country, due to poor economic policies [14, 15]. Livestock produce meat, milk, eggs, manure, fibers, hides and horns, and demand for these products is rapidly growing due to population growth, urbanization in developing countries, and increased revenue [16]. The livestock sector is often maligned, but it still plays a vital role in the country’s economy by providing draught power, valuable organic animal proteins, and other by-products. Manure and draught power provided by the animals enhance the supply of organic matter to improve land fertility and aid productivity, respectively. More than 10 million animals are engaged in agricultural activities and events [17].

There are many factors inhibiting the growth of the livestock sector in Pakistan including policy issues, rapid deterioration of rangelands, unhygienic eating practices, poor marketing systems, inadequacy of extension services, and insufficient resources. There are several fatal animal diseases in Pakistan including foot and mouth disease (FMD), hemorrhagic septicemia (HS), bovine viral diarrhea (BVD), and black quarter (BQ). Farmers do not regularly vaccinate their animals against these fatal diseases which lowers dairy production. Many cows/buffalos, for example, seem to suffer from mastitis, greatly contributing to the loss of milk production. The consequences of livestock diseases are generally seen as direct impacts only, but in reality they can be quite complex. The diseases affect the productivity of animals and deprive farmers of their possible daily earnings. These fatal diseases lead to morbidity resulting in short- or long-term product loss [18].

Pakistan has been also home to a number of field veterinary ethnobotanical studies conducted in various areas of the country over the last two decades. These studies have sometimes been carried out as part of broader ethnobotanical surveys. The main purpose of these published studies we reviewed was to investigate and document ethnoveterinary herbal knowledge without any consideration of possible cross-cultural, spatial, and/or temporal variations. Since these surveys were conducted in restricted areas and were published in various literature sources, no in-depth reviews have so far analyzed the overall folk uses of plants for animal diseases in Pakistan, and this review wanted to fill this gap. Suroowan et al. [19] recently reviewed the ethnoveterinary plants of South Asia, but the review considered only a few Pakistani studies and no in-depth analysis and interpretation of the data were carried out.

Hundreds of medicinal plants have been used for centuries in folk veterinary systems in all areas of Pakistan. Ethnobotany in Pakistan has partially addressed these veterinary plant remedies, since most of the studies have focused on medicinal plants for humans and only sporadically on wild food plants. Local shepherds and herbalists living in mountainous and marginal areas were and still are particularly knowledgeable in managing animal care via herbal practices [19]. The information presented in the current review can provide baseline data for implementing culturally appropriate rural developments programs and for fostering the actual use of veterinary Complementary and Alternative Medicine.

The main objectives of this study were:

-

(a)

To analyze all the field studies reporting ethnoveterinary plant uses in Pakistan

-

(b)

To assess cross-cultural and cross-regional variations in the folk utilization of veterinary plants in Pakistan.

Methods

Selection of the ethnoveterinary herbal literature

For this review, all published articles reporting medicinal plants used in traditional veterinary practices in Pakistan were considered. The literature was thoroughly searched using online databases and platforms such as Scopus, PubMed, and Web of Science, ResearchGate and Academia. In searching the databases some key words were used (ethnoveterinary; ethnobotany; Pakistan) to elicit data on the ethnoveterinary herbal practices for the review. Although extensive literature exists on Pakistani ethnobotany, we only targeted those research articles that were published exclusively on ethnoveterinary herbal practices in the country. In total, 35 peer reviewed articles published in international journals, in English, focusing on ethnoveterinary herbal practices were found, dating from 2004 to May 2018 and from all over the country. It is worth mentioning here that a number of reviewed studies missed some crucial ethnobotanical information in terms of plant folk names, voucher specimen numbers, informants and study site selection criteria, and details on remedy preparations, administrations, and animals treated.

Statistical analysis

Phillips and Gentry [20] adopted the following formula in order to analyze the cultural importance of botanical species:

where Uis represents the number of uses mentioned by all informants for a given species is (use reports for species s) and Nis is the total number of informants that reported species s.

In this review study, species Use Values (UVs) and family Use Values (UVf) were employed by modifying the equation for UVis, as proposed by Tardío and Pardo-de-Santayana [21]:

where Us represents the number of uses mentioned by all pseudoinformants for a given species s (use reports for species s) and Ns is the total number of pseudoinformants that reported species s;

where Uf represents the number of uses mentioned by all pseudoinformants for a given family f (use reports for the family f) and Nf is the total number of pseudoinformants that reported family f.

In the statistical analysis, we adopted the concept of “pseudoinformant” as described by Tardío and Pardo-de-Santayana [22]. The term “pseudoinformant” in this review referred to each individual considered ethnoveterinary study rather than the original informants that reported plants in each of the conducted field studies.

Phytopharmacological review

A comprehensive literature survey was carried out to review the pharmacological evidence for the least known medicinal plants reported in the reviewed ethnoveterinary studies and used in the country. In PubMed we searched out every medicinal plant species for their phytopharmacological profiles. Based on their lowest UVs, a total of 30 medicinal plants were selected and investigated for their respective pharmacological and/or phytochemical potential. The assumption we made here was that the most commonly used ethnoveterinary plants in Pakistan have already been well studied bioscientifically. These 30 species have thus far been very rarely investigated.

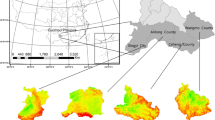

Cross-cultural and cross-regional comparative analysis

Data obtained from the selected articles were categorized into three major groups: (a) veterinary medicinal plants used by Pathan communities in mountainous regions; (b) veterinary medicinal plants used by non-Pathan communities in mountainous regions; and (c) veterinary medicinal plant used in plain areas. The adopted categorization was made in order to divide the analyzed ethnoveterinary literature into three equal groups, which had to be able to show variations in geographical and cultural variables. Due to an insufficient number of studies on ethnoveterinary practices in Pakistan, it was only possible to consider data coming from all non-Pathan communities grouped together.

To compile the data systematically, an MS Excel spreadsheet was used in which the botanical names of plants, botanical families, parts used, mode of preparation and administration, and disease treated were recorded. The scientific names of the reported taxa were updated using The Plant List database [23]. Data was arranged in tabulated form. To deal with possible gaps in the selected ethnoveterinary studies, a separate table (Table 1, [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57]) was created, presenting information about the local names of plants, voucher specimen numbers, description of the study area, language, and typology of the study participants in the selected studies. For cross-cultural and cross-regional analysis of reported medicinal taxa and their uses, the extracted data was tabulated, sorted, and organized in MS Excel, and then the results were displayed using Venn diagrams.

The dichotomy between Pathan and non-Pathan peoples has been an important trajectory in the cultural history of Pakistan. Pashto speaking people are referred to as Pathans in Pakistan, while they are mainly known also as Pashtuns or Afghans in the international literature. Pashto has been classified as an Eastern Iranian language which, according to MacKenzie [58], derived from the Aryan family of languages that “divided into its distinct Indian and Iranian branches more than three millennia ago.” In Pakistan, Pashto is spoken in the North Western districts. It is also spoken in Northeastern Baluchistan, and in Punjab it is still spoken in border areas of Mianwali and Attock. Additionally, the whole tribal area between Pakistan and Afghanistan is Pashto-speaking. Pashto is also one of the two most used official languages of Afghanistan. In Afghanistan, the Pashto-speaking area is in the East, South, and Southwest [59]. According to Gankovsky, the fundamentals of the original Pathan culture have evolved from the second millennium AD onwards [60]. The traditional life style of Pathans is encapsulated in Pakhtunwali, an orally transmitted customary code that includes vengeance (Badal), hospitality (Melmastia), and forgiveness (Nanawati), which has been remarkably described by the Norwegian anthropologist Fredrick Barth (1928-2016) [61].

Results and discussion

Herbal veterinary remedies of Pakistan

In Pakistan, hundreds of medicinal plants are used for treating livestock in remote areas where access to modern drugs is limited and people have sufficient knowledge about traditional therapies. The selected studies for the review indicated that a diversity of medicinal plants have remained popular among rural population across the country. Pakistani lay people, shepherds, farmers, nomadic grazers, and traditional healers used these medicinal plants to treat animal diseases and the selected studies recorded this traditional knowledge (Table 1). The current review reports 474 ethnoveterinary plants from different communities around the country that were used to treat domestic animals (Additional file 1: Table S2). Geographical distribution of the reported studies reveal that among the 35 studies, 14 studies were carried out in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, 11 in Punjab, and four in Azad Kashmir, while Gilgit-Baltistan, Sindh, and Baluchistan were the least investigated areas in this regard with only three, two, and one studies, respectively (Table 1).

Researchers obtaining access to all regions of the country equally is a big hurdle to carrying out field studies. More specifically, the lack of ethnoveterinary literature from Baluchistan may be due to its restricted access to field researchers in the region. Living in the largest province of Pakistan, the people of Baluchistan are relatively more dependent on natural resources and keeping domestic animals in order to generate revenue in hard times [62]. More importantly, the remote communities of the province keep herds of domestic animals, and therefore the lack of literature does not mean that people residing in the region are not dependent on traditional therapies but rather that the difficult conditions which involve several factors including poor government policy prevented scientists from carrying out studies [63]. With regard to Sindh, the lack of reliable data on ethnoveterinary herbal remedies may involve some particular factors, obviously different from those of Baluchistan. Sindh region also plays an important role in agriculture and livestock production of the country. Sindh is comprised of plain areas and many big cities, and people living in remote and marginal areas keep animals to earn their livelihood, which can be seen in different spots on several occasions [64]. In general, people living in rural areas of inner Sindh are economically underprivileged and very few ethnoveterinary herbal studies have been conducted there.

In this review, we recorded 2386 veterinary remedies (Additional file 1: Table S2, Fig. 1). Most remedies were prepared in the form of powder (Table 2). Frequently treated diseases included digestive and skin problems with 606 and 361 use reports, respectively (Fig. 2). The dominance of digestive problems as the main target of local herbal ethnoveterinary practices may be due to the lack of clean drinking water, unhygienic fodder consumption, and, most importantly, the fact that locals prefer to use herbs for minor animal complaints. It has been documented that poor fodder quality has significant negative impacts on animal health. As most parasitic diseases are concerned with the gastrointestinal tract, researchers have argued that nutrition status, pasture management, climatic conditions, animal immunity, and host preference are the major factors involved in the prevalence of different parasitic infections [65]. Grace et al. [66] reported that massive under-reporting, lack of veterinary surveillance activities, and few field-diagnostic facilities have been the possible causes of hindrance in in-depth establishing the true status of animal health in Pakistan.

Descriptive statistics indicated that highest number of use reports was for Brassica rapa (86 use reports), Foeniculum vulgare (51), Trachyspermum ammi (50), Allium cepa (43), Citrullus colocynthis (43), and Melia azedarach (35) (Additional file 1: Table S2). Some plants were recorded quite frequently, including Brassica rapa (23), Foeniculum vulgare (20 articles reported), Allium cepa (19), Allium sativum (18), Melia azedarach (17), Citrullus colocynthis (16), and Ricinus communis (15). The wide acceptance of these particular medicinal plants may not only be due to their efficient activity but also involve a few other factors like their large availability in markets and their possible long history of use in the traditional medicine practiced by healers, making their use more feasable than the use of plants which are difficult to harvest [67]. Moreover, the use of medicinal plants in a given area is also shaped by the familiarity of local communities with their landscape, type of vegetation, seasonality, and ease of availability of herbal material [68].

The predominant botanical families were Poaceae (41 species; 144 use reports per family), Asteraceae (32; 107), and Fabaceae (29; 127) (Table 3, Fig. 1). These families have frequently been reported in a wide range of ethnobotanical studies [34, 69, 70]. The prevalence of the aforementioned botanical families shows that locals prefer to use plants growing in anthropogenic environments, i.e., plants that grow close to home gardens. Looking at the results obtained for each family in terms of use reports, it could be interpreted that the member plants of these families may have some specific effective pharmacologically active ingredients making them favorable in treating various ailments. The familiarity of local people with particular medicinal plants is also dependent upon their long-term perception based on continuous exposure to these natural resources. Furthermore, Pinaceae, Apiaceae, Poaceae, Brassicaceae, and Solanaceae families had the highest Use Values: 7.50, 6.35, 6.00, 5.71, and 5.31, respectively (Table 3).

The reviewed data confirmed that ethnoveterinary herbal remedies play a large role in Pakistan, especially in the most remote areas of the country; moreover, the remarkable heritage that emerges from the data reveals a robust link to very common pastoral activities and possibly also to the traditional pastoralist heriatge of most people inhabiting the rural areas [71].

Little-known veterinary plants of Pakistan

Research on natural products is sometimes based on ethnobotanical information. One goal of ethnopharmacology is to improve our understanding of the pharmacological effects of traditionally used medicinal plants, especially for the benefts of rural remote communities that are highly marginalized and poverty stricken. In this section, we stress the need for the phytotherapeutical evaluations of those medicinal plants that have rarely been reported in the ethnoveterinary of Pakistan and have scarcely been investigated in previous pharmacological studies.

Abutilon theophrasti

The pharmacology of Abutilon theophrasti has rarely been investigated and only one potential and relevant study was found which indicated that methanolic extracts of the species have useful antifungal effects against selected fungal species [72]. Quercetin, an isolated flavonoid from the aqueous extract of Abutilon theophrasti seeds, has been reported to have a significant inhibitory effect on the growth of Aspergillus niger and Fusarium spp [118].

Actaea spicata

Researchers have claimed that trans-aconitic acid, isolated from ethanolic fractions of Actaea spicata, exhibits cytostatic action against Ehrlich’s ascites tumor [73]. Significant antioxidant activity of methanol extract and ethyl acetate fraction has been recorded for the species [74]. Similarly, its petroleum, ether, chloroform, methanol, and water extracts have exhibited antidepressant activity in experimental mice [75].

Aizoon canariense

Looking at the pharmacological activities of different extracts of Aizoon canariense, it has been mentioned that they exhibit moderate scavenging activity, as well as antibacterial, antifungal [76], and antioxidant activity [77].

Anagallis arvensis

Various extracts of Anagallis arvensis have shown strong antifungal activity [78,79,80,81]. The plant has antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects [79], and molluscicidal activity [82]. Strong molluscicidal activity was found for its saponins, namely desglucoanagalloside B and anagalloside B [82]. An acetyl saponin isolated from the plant was found to possess marked taenicide activity [83]. Triterpene saponins exhibit oestrogenic activity [84]. Moroever, strong antifungal and antiviral activities of Anagallis saponins were also demonstrated [119,120,121].

Angelica glauca

Previous studies revealed that butylidene phthalide, derived from Angelica glauca, possesses antispasmodic activity [85]. Irshad et al. [86] reported that the essential oil (EO) of Angelica glauca exhibits good radical scavenging and peroxidation inhibition activities, and showed appreciable antimicrobial activity. Sharma et al. [87] reported that the EO of Angelica glauca exhibited broncho-relaxant activity against histamine and ovalbumin-induced broncho constriction in guinea pigs.

Buddleja asiatica

Buddleja asiaticaextracts have shown antimicrobial, antioxidant [88,89,90], antihepatotoxic [91], antispasmodic, and Ca++ antagonist activity [88].

Cocculus hirsutus

A variety of pharmacological activities have been exhibited by different extracts of Cocculus hirsutus, such as anti-diabetic activity [92], antihyperglycemic activity [93], anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects [94, 95], antimicrobial activity [96], diuretic activity, and laxative effects in different experiments [97]. The plant is well documented as a spermatogenic [92].

Cochlospermum religiosum

The bioactive secondary metabolite myricetin was isolated from in vivo and in vitro tissue samples of Cochlospermum religiosum. Myricetin is a naturally occurring flavonol found in many plants, having a wide array of biochemical properties, such as antineoplastic and anti-carcinogenic antioxidant activity, and also anti-inflammatory effects [98]. The plant is well documented for its antimicrobial potential by a number of researchers [99, 100] as well as for its immunomodulatory effects [101]. Ethanolic extract of Cochlospermum religiosum yielded promising results with respect to hepatoprotective activity [102]. Isorhamnetin, a flavonoid glycoside isolated from the plant, exhibited an antioxidant effect [103, 104].

Cynanchum viminale

One study has demonstrated the effect of the aqueous extract of Cynanchum viminale leaves as an analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antipyretic in albino mice, which justify the traditional use of this plant [105].

Debregeasia saeneb

A study has demonstrated that Debregeasia saeneb exhibits potential anticancer activity [106].

Dichanthium annulatum

This plant has good anticancer effects [107]. Results revealed that the aerial parts of Dichanthium annulatum possess good antioxidant and antimicrobial activity [108].

Flueggea leucopyrus

The extract of this plant possesses significant antioxidant activity [109, 110] and antiproliferative properties, and it induced apoptosis in HEp-2 cells [110]. Ethanol extract of Flueggea leucopyrus leaves increases sexual behavior in rats, supporting its use as an aphrodisiac [111].

Litsea monopetala

Different extracts of Litsea monopetala exhibit anticancer properties [112] and antioxidant activity [113, 114].

Silene villosa

The methanolic extract of Silene villosa plays a protective role, while the alcoholic extract is active against CCl4-induced cardiac and renal toxicity in rats [115]. The alcoholic extract of the plant has also shown anti-inflammatory, wound healing, and hepatoprotective properties [116], as well as a cytotoxic effect [117].

After comprehensive bio-medical review of the recorded species, some medicinal plants reported in Table S2 were found to have not been pharmacologically in-depth investigated, including Agrostis gigantea, Allardia tomentosa, Aristida adscensionis, Bothriochloa bladhii, Dactylis glomerata, Dracocephalum nuristanicum, Launaea nudicaulis, Sibbaldianthe bifurca, Spiraea altaica, and Thalictrum foetidum. Lack of substantial research on these and other little-known veterinary plants indicates that robust effort is still needed to fill the gaps existing between the inputs arising from the ethnobotanical data and the actual body of phytopharmacological knowledge.

Cross-cultural comparison

Ethnoveterinary herbal data was subjected to cross cultural comparison via Venn diagrams. In order to assess the effect of ethnicity in shaping ethnoveterinary practices, we compared the ethnoveterinary plants used by Pathan and non-Pathan ethnic communities across the country.

As described in previous paragraphs, Pathans populate the North-West of Pakistan and their human ecology has been particularly characterized by a very prominent pastoralist trajectory [122].

Cross-cultural comparative assessment indicated that approximately only one-third (134 plants; 28.3%) of the 474 medicinal plants were commonly used by both Pathans and non-Pathans (Fig. 3). Moreover, we considered the medicinal plants quoted by both Pathans and non-Pathans for further comparison in terms of their use reports and we found 101 (8%), out of 1205 total, which were shared by both groups (Fig. 3). This figure demonstrates that veterinary plants which are used by both groups are prepared and used in very different ways. The small overlap of the aforementioned use reports may suggest that detailed practices and experiences of local communities with their plants are largely divergent. The pattern of the above results might be also related to the epidemiological issues which cannot be ignored as every region has particular socio-environmental conditions which may affect the prevalence of specific animal diseases leading to certain medicinal plant uses instead of others.

Cross-regional comparison

In order to evaluate how geographical and ecological factors may have affected indigenous practices, the recorded data were subjected to regional comparison. Ethnoveterinary data was divided into three clusters, namely plants used by Pathan groups in mountain areas (a), plants used by non-Pathan groups in mountain areas (b), and plants used by non-Pathan groups in plain areas (c), and then the three clusters were represented via Venn diagrams (Fig. 4). Figure 4 shows (A) the overalap of the overall recorded veterinary plants and (B) the overlap of those Use Reports which refer only to those species that were reported by all three groups (59 taxa, 12.4% of the overall 474 medicinal plants, Fig. 4A). Only 11 out of the 763 plant Use Reports (1.4%) were shared among the three aforementioned groups. Figure 4B suggests that even those plants that were recorded among all three groups have actually within each cluster very different, probably locally situated, veterinary uses. Regional comparative analysis shows also that only 74 (9.7%) out of 763 plant reports are shared by local communities living in the mountain and in plain areas. These findings indicate that the divergences of actual plant utilizations are remarkable and that the difference between the plants used by Pathans and non-Pathans is somehow similar to the difference between plants used in plain and mountain areas. This pattern suggests that both geography/ecology and ethnicity/cultural customs have played a crucial role in shaping folk veterinary herbal knowledge in Pakistan.

Conclusion

The current review revealed that in Pakistan, local communities have used and are possibly still using hundreds of medicinal plants to treat their domestic animals for generations. This remarkable cultural heritage may be linked to the pastoralist origin of many populations inhabiting the country, among which the Pathans living in the North-West of the country. Cross-cultural comparison showed that Pathan and non-Pathan ethnic communities share approximately one-third only of the medicinal plants and only 8% of the use reports (referred to the most commonly quoted plants). Cross-regional comparative analysis showed instead that only 12% of the overall quoted veterinary plants were shared between mountain and plain areas, suggesting that both ecological and cultural factors have played a role in shaping this remarkable veterinary heritage.

Furthermore, the literature review indicated that there are still some medicinal plants, as reported here, that need detailed phytochemical and pharmacological study to investigate their exact phytotherapeutical profiles. The promotion of the recorded ethnoveterinary heritage by stakeholders involved in rural development projects may be essential for improving animal well-being and presumably the quality of animal food products as well.

Availability of data and materials

All the data can be found in the article.

References

Mathius-Mundy E, McCorkle CM. Ethnoveterinary medicine: an annotated bibliography. Ames: Iowa State University; 1989.

Wanzala W, Zessin KH, Kyule NM, Baumann MP, Mathia E, Hassanali A. Ethnoveterinary medicine: a critical review of its evolution, perception, understanding and the way forward. Livestock Res Rural Dev. 2005;17:119.

McCorkle CM. An introduction to ethnoveterinary research and development. J Ethnobiol. 1986;6:129–49.

McGaw LJ, Abdalla MG, editors. Ethnoveterinary medicine. Present and future concepts. Cham: Springer; 2020.

Said HM. Hamdard Medicus. Karachi: Hamdard Foundation Pakistan; 1998.

Guèye EF. Ethnoveterinary medicine against poultry diseases in African villages. World's Poult Sci J. 1999;55:187–98.

McGaw LJ, Eloff JN. Ethnoveterinary use of southern African plants and scientific evaluation of their medicinal properties. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;119:559–74.

van der Merwe D, Swan GE, Botha CJ. Use of ethnoveterinary medicinal plants in cattle by Setswana-speaking people in the Madikwe area of the North West Province of South Africa. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 2001;72:189–96.

Akhtar M, Iqbal Z, Khan M, Lateef M. Anthelmintic activity of medicinal plants with particular reference to their use in animals in the Indo-Pakistan subcontinent. Small Ruminant Res. 2000;38:99–107.

Martin M, Mathia E, McCorkle MC. Ethnoveterinary medicine. An annotated bibliography of community animal healthcare. London: ITDG Publ.; 2001.

Rehman A, Jingdong L, Chandio AA, Hussain I. Livestock production and population census in Pakistan: determining their relationship with agricultural GDP using econometric analysis. Inf Process Agric. 2017;4:168–77.

Food and Agriculture Organization. The state of food and agriculture. Livestock in the balance. Rom: FAO; 2009. Available from: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i0680e.pdf. (Accessed 13th April 2020).

Economic Survey of Pakistan. Islamabad: Government of Pakistan; 2010.

Quddus MA, Davies SP, Lybecker DW. The livestock economy of Pakistan: an agricultural sector model approach. Pak Dev Rev. 1997;36:171–90.

Simon JL. Resources, population, environment: an oversupply of false bad news. Sci. 1980;208:1431–7.

Delgado CL. Rising demand for meat and milk in developing countries: implications for grasslands-based livestock production. In: McGilloway DA (ed.) Grassland: a global resource. Proceedings of the XX International Grassland Congress, Dublin, Ireland, 26-30 June 2005. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers. 2005;29–39.

Raza SH. Role of draught animals in the economy of Pakistan. Edinburgh: Center for Tropical Veterinary Medicine, University of Edinburgh; 2000.

Hasnain HU, Usmani RH. Livestock of Pakistan. Islamabad: Livestock Foundation; 2006.

Suroowan S, Javeed F, Ahmad M, Zafar M, Noor MJ, Kayani S, et al. Ethnoveterinary health management practices using medicinal plants in South Asia–a review. Vet Res Commun. 2017;41:147–68.

Phillips O, Gentry A. The useful plants of Tambopata, Peru: I Statistical hypotheses tests with a new quantitative technique. Econ Bot. 1993;47:15–32.

Tardío J, Pardo-de-Santayana M. Cultural importance indices: a comparative analysis based on the useful wild plants of southern Cantabria (Northern Spain). Econ Bot. 2008;62:24–39.

Tardío J, Pardo-de-Santayana M. Ethnobotanical analysis of wild fruits and vegetables traditionally consumed in Spain. In: de Cortes Sánchez-Mata, M., Tardío, Javier editors. Mediterranean Wild Edible Plants. Ethnobotany and Food Composition Tables. New York: Springer; 2016; 57-79.

The Plant List. 2013. Version 1.1. (http://www.theplantlist.org. Accessed 1st January 2020).

Abbasi AM, Khan SM, Ahmad M, Khan MA, Quave CL, Pieroni A. Botanical ethnoveterinary therapies in three districts of the Lesser Himalayas of Pakistan. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2013;9:84.

Ahmad K, Ahmad M, Weckerle C. Ethnoveterinary medicinal plant knowledge and practice among the tribal communities of Thakht-e-Sulaiman hills, West Pakistan. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;170:275–83.

Ahmed MJ, Murtaza G. A study of medicinal plants used as ethnoveterinary: harnessing potential phytotherapy in Bheri, District Muzaffarabad (Pakistan). J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;159:209–14.

Ali I, Hussain H, Batool H, Dad A, Raza G, Falodun A, et al. Documentation of ethno veterinary practices in the CKNP region, Gilgit-Baltistan. Int J Phytomedicine. 2017;9:223–40.

Aziz MA, Adnan M, Khan AH, Sufyan M, Khan SN. Cross-cultural analysis of medicinal plants commonly used in ethnoveterinary practices at South Waziristan Agency and Bajaur Agency, Federally Administrated Tribal Areas (FATA), Pakistan. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018;210:443–68.

Badar N, Iqbal Z, Sajid MS, Rizwan HM, Jabbar A, Babar W, et al. Documentation of ethnoveterinary practices in district Jhang, Pakistan. J Anim Plant Sci. 2017;27:398–406.

Deeba F, Muhammad GH, Iqbal ZA, Hussain I. Appraisal of ethno-veterinary practices used for different ailments in dairy animals in peri-urban areas of Faisalabad (Pakistan). Int J Agric Biol. 2009;11:535–41.

Dilshad SM, Iqbal Z, Muhammad G, Iqbal A, Ahmed N. An inventory of the ethnoveterinary practices for reproductive disorders in cattle and buffaloes, Sargodha district of Pakistan. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;117:393–402.

Dilshad SR, Rehman NU, Ahmad N, Iqbal A. Documentation of ethnoveterinary practices for mastitis in dairy animals in Pakistan. Pak Vet J. 2010;30:167–71.

Farooq Z, Iqbal Z, Mushtaq S, Muhammad G, Iqbal MZ, Arshad M. Ethnoveterinary practices for the treatment of parasitic diseases in livestock in Cholistan desert (Pakistan). J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;118:213–9.

Harun N, Chaudhry AS, Shaheen S, Ullah K, Khan F. Ethnobotanical studies of fodder grass resources for ruminant animals, based on the traditional knowledge of indigenous communities in Central Punjab Pakistan. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2017;13:56.

ul Islam M, Anwar Z, Tabassum S, Khan SA, Zeb AC, Abrar M, et al. Plants of ethno-veterinary uses of Tunglai mountain Baffa Mansehra, Pakistan. Int J Anim Vet Adv. 2012;4:221–4.

Hussain A, Khan MN, Iqbal Z, Sajid MS. An account of the botanical anthelmintics used in traditional veterinary practices in Sahiwal district of Punjab, Pakistan. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;119:185–90.

Khan MI, Hanif W. Ethno veterinary medicinal uses of plants from Samalini valley Dist. Bhimber, (Azad Kashmir) Pakistan. Asian J Plant Sci. 2006;5:390–6.

Khan MA, Ullah AS, Rashid AB. Ethnoveterinary medicinal plants practices in district Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Pakistan. Pak J Bot. 2015;47:105–14.

Khan FM. Ethno-veterinary medicinal usage of flora of Greater Cholistan desert (Pakistan). Pak Vet J. 2009;29:75–80.

Khan MA, Khan MA, Mujtaba G, Hussain M. Ethnobotanical study about medicinal plants of Poonch valley Azad Kashmir. J Anim Plant Sci. 2012;22:493–500.

Khan KU, Shah M, Ahmad H, Ashraf M, Rahman IU, Iqbal Z, et al. Investigation of traditional veterinary phytomedicines used in Deosai Plateau, Pakistan. Global Vet. 2015;15:381–8.

Khattak NS, Nouroz F, Rahman IU, Noreen S. Ethno veterinary uses of medicinal plants of district Karak, Pakistan. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;171:273–9.

Khuroo AA, Malik AH, Dar AR, Dar GH, Khan ZS. Ethnoveterinary medicinal uses of some plant species by the Gujjar tribe of the Kashmir Himalaya. Asian J Plant Sci. 2007;6:148–52.

Mirani AH, Mirbahar KB, Bhutto AL, Qureshi TA. Use of medicinal plants for the treatment of different sheep and goat diseases in Tharparkar, Sindh, Pakistan. Pak J Agric Agric Eng Vet Sci. 2014;30:242–50.

Muhammad G, Khan MZ, Hussain MH, Iqbal Z, Iqbal M, Athar M. Ethnoveterinary practices of owners of pneumatic-cart pulling camels in Faisalabad City (Pakistan). J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;97:241–6.

Mussarat S, Amber R, Tariq A, Adnan M, NM AE, Ullah R, Bibi R. Ethnopharmacological assessment of medicinal plants used against livestock infections by the people living around Indus river. BioMed Res Int. 2014;616858.

Raza MA, Younas M, Buerkert A, Schlecht E. Ethno-botanical remedies used by pastoralists for the treatment of livestock diseases in Cholistan desert, Pakistan. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;151:333–42.

Raziq A, de Verdier K, Younas M. Ethnoveterinary treatments by dromedary camel herders in the Suleiman Mountainous Region in Pakistan: an observation and questionnaire study. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2010;6:16. .

Shah GM, Ahmad M, Arshad M, Khan MA, Zafar M, Sultana S. Ethno-phytoveterinary medicines in northern Pakistan. J Anim Plant Sci. 2012;22:791–7.

Sher H, Hussain F, Mulk S, Ibrar M. Ethnoveternary plants of Shawar Valley, District Swat, Pakistan. Pak J Pl Sci. 2004;10:35–40.

Sindhu ZU, Zafar I, Khan MN, Jonsson NN, Muhammad S. Documentation of ethnoveterinary practices used for treatment of different ailments in a selected hilly area of Pakistan. Int J Agric Biol. 2010;12:353–8.

Sindhu ZU, Ullah S, Rao ZA, Iqbal Z, Hameed M. Inventory of ethno-veterinary practices used for the control of parasitic infections in district Jhang, Pakistan. Int J Agric Biol. 2012;14:922–8.

Tariq A, Mussarat S, Adnan M, NM AE, Ullah R, Khan AL. Ethnoveterinary study of medicinal plants in a tribal society of Sulaiman range. Sci World J. 2014;127526.

Tariq A, Adnan M, Mussarat S. Use of ethnoveterinary medicines by the people living near Pak-Afghan border region. Slov Vet Res. 2016;53:119–30.

ul Islam M, Anwar Z, Tabassum S, Khan SA, Zeb AC, Abrar M, et al. Plants of ethnoveterinary uses of Tunglai mountain Baffa Mansehra, Pakistan. Int J Anim Vet Adv. 2012;4:221–4.

Ullah Z, Shah GM, Muhammad S, Muhammad Z, Ullah R, Majeed A. Ethnoveterinary plants used for animal cure in District Charsadda, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Pakistan). Spec J Biol Sci. 2017;3:1–19.

Yousufzai SA, Nasrullah K, Muhammad W, Muhammad A. Ethnomedicinal study of Marghazar valley, Pakistan. Int J Biol Biotechnol. 2010;7:409–16.

MacKenzie DN. A standard Pashto. B Sch Orient Afr St. 1959;22:231–5.

Rahman T. The Pashto language and identity-formation in Pakistan. J Contemp South Asia. 1995;4:151–70.

Gankovsky YV. The peoples of Pakistan. An ethnic history. Lahore: People's Publ. House; 1973.

Barth F. Ethnic Groups and Boundaries. The Social Organization of Culture Difference. Bergen: Universitetsforlaget; 1969.

Government of Pakistan. Pakistan Livestock Census 2006; Lahore: Pakistan Bureau of Statistics; 2006. .

Raziq A, Younas M, Rehman Z. Prospects of Livestock Production in Balochistan. Pak Vet J. 2010;30:181–6.

Wasim MP. Trends and growth in livestock population in Sindh: a comparison of different censuses. Indus J Manage Soc Sci. 2007;1:58–75.

Blood DC, Henderson JA, Radostits OM, Arundel JH, Gay CC. Veterinary medicine: a textbook of the diseases of cattle, horses, sheep, pigs and goats. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1979.

Grace D, Mutua F, Ochungo P, Kruska R, Jones K, Brierley L, et al. Mapping of poverty and likely zoonoses hotspots. Zoonoses Project 4. Report to the UK Department for International Development. Nairobi, ILRI; 2012. Available from: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/21161/ZooMap_July2012_final.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y. (Accessed 13th April 2020).

Shinwari ZK. Medicinal plants research in Pakistan. J Med Plants Res. 2010;4:161–76.

Petrovska BB. Historical review of medicinal plants’ usage. Pharmacogn Rev. 2012;6:1–5.

Chahal M, Yadav JP. Enumeration of ethnobotanical plants of family Poaceae from Central and South Haryana. J Econ Taxon Bot. 2013;37:786–93.

Umair M, Altaf M, Abbasi AM (2017) An ethnobotanical survey of indigenous medicinal plants in Hafizabad district, Punjab-Pakistan. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0177912. .

Ojeda G, Rueff H, Rahim I, Maselli D. Sustaining mobile pastoralists in the mountains of northern Pakistan. Evidence for Policy Series, Regional Edition Central Asia 2012;3. Available from: https://boris.unibe.ch/17618/1/Regional_Policy_Brief_03_Central_Asia_Supporting_Pastoralists_143947757826.pdf. (Accessed 13th April 2020). .

Hassan M, Habib H, Kausar N, Ma Z, Mir RA. Evaluation of root and leaf of Abutilon theophrasti medik for antifungal activity. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2016;9:75–7.

Nikonov GK, Syrkina-Krugliak SA. Chemical analysis of the active principle in Actaea spicata L. Aptechn Delo. 1963;12:36–9.

Madaan R, Sharma A. Evaluation of anti-anxiety activity of Actaea spicata linn. Int J Pharm Sci Drug Res. 2011;3:45–7.

Batra S, Kumar S. Antidepressant activity evaluation of Actaea spicata L. roots. J Fundam Pharm Res. 2014;2:1–6.

El-Amier YA, Haroun SA, El-Shehaby OA, Al-hadithy ON. Antioxidant and antimicrobial of properties of some wild Aizoaceae species growing in Egyptian Desert. J Environ Sci. 2016;45:1–10.

Al-Laith AA, Alkhuzai J, Freije A. Assessment of antioxidant activities of three wild medicinal plants from Bahrain. Arabian J Chem. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2015.03.004.

Ali-Shtayeh MS, Abu Ghdeib SI. Antifungal activity of plant extracts against dermatophytes. Mycoses. 1999;42:665–72.

López V, Jäger AK, Akerreta S, Cavero RY, Calvo M. Pharmacological properties of Anagallis arvensis L. “blue pimpernel” and Anagallis foemina Mill. “blue pimpernel” traditionally used as wound healing remedies in Navarra. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;134:1014–7.

Bahraminejad S, Abbasi S, Fazlali M. In vitro antifungal activity of 63 Iranian plant species against three different plant pathogenic fungi. Afr J Biotechnol. 2011;10:16193–201.

Bahraminejad S, Amiri R, Ghasemi S, Fathi N. Inhibitory effect of some Iranian plant species against three plant pathogenic fungi. Int J Agric Crop Sci. 2013;5:1002–8.

Abdel-Gawad MM, El-Amin SM, Ohigashi H, Watanabe Y, Takeda N, Sugiyama H, et al. Molluscicidal saponins from Anagallis arvensis against schistosome intermediate hosts. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2000;53:17–9.

Khare CP. Indian medicinal plants: An illustrated dictionary. New York: Springer; 2007.

Wahby AM. Egyptian plants poisonous to animal. Cairo: El-Horia; 1940.

Hsieh MT, Wu CR, Lin LW, Hsieh CC, Tsai CH. Reversal caused by n-butylidenephthalide from the deficits of inhibitory avoidance performance in rats. Planta Med. 2001;67:38–42.

Irshad M, Shahid M, Aziz S, Ghous T. Antioxidant, antimicrobial and phytotoxic activities of essential oil of Angelica glauca. Asian J Chem. 2011;23:1947–51.

Sharma S, Rasal VP, Patil PA, Joshi RK. Effect of Angelica glauca essential oil on allergic airway changes induced by histamine and ovalbumin in experimental animals. Indian J Pharmacol. 2017;49:55–9.

Ali F, Ali I, Khan HU, Khan AU, Gilani AH. Studies on Buddleja asiatica antibacterial, antifungal, antispasmodic and Ca++ antagonist activities. Afr J Biotechnol. 2011;10:7679–83.

Dawidar AM, Khalaf OM, Abdelmajeed SM, Abdel-Mogib M. Phytochemical and biological evaluation of Buddleja asiatica. Res J Pharm Biol Chem Sci. 2015;6:680–93.

El-Sayed MM, Abdel-Hameed ES, Ahmed WS, El-Wakil EA. Non-phenolic antioxidant compounds from Buddleja asiatica. Z Naturforsch C. 2008;63:483–91.

El-Domiaty MM, Wink M, Aal MM, Abou-Hashem MM, Abd-Alla RH. Antihepatotoxic activity and chemical constituents of Buddleja asiatica Lour. Z Naturforsch C. 2009;64:11–9.

Sangameswaran B, Jayakar B. Anti-diabetic and spermatogenic activity of Cocculus hirsutus (L) Diels. Afr J Biotechnol. 2007;6:1212–6.

Badole S, Patel N, Bodhankar S, Jain B, Bhardwaj S. Antihyperglycemic activity of aqueous extract of leaves of Cocculus hirsutus (L.) Diels in alloxan-induced diabetic mice. Indian J Pharmacol. 2006;38:49–53.

Nayak S, Singhai AK. Antimicrobial activity of the roots of Cocculus hirsutus. Ancient Sci Life. 2003;22:101–5.

Sengottuvelu S, Rajesh K, Sherief SH, Duraisami R, Vasudevan M, Nandhakumar J, et al. Evaluation of analgesic and anti-inflammatory activity of methanolic extract of Cocculus hirsutus leaves. J Res Educ Indian Med. 2012;18:175–82.

Jeyachandran R, Mahesh A, Cindrella L, Baskaran X. Screening Antibacterial Activity of Root Extract of Cocculus hirsutus (L.) Diels. used in Folklore Remedies in South India. J Plant Sci. 2008;3:194–8.

Badole SL, Bodhankar SL, Patel NM, Bhardwaj S. Acute and chronic diuretic effect of ethanolic extract of leaves of Cocculus hirsutus (L.) Diles in normal rats. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2009;61:387–93.

Pandey A, Sharma A, Lodha P. Isolation of an anti-carcinogenic compound: myricetin from Cochlospermum religiosum. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2015;6:2146–52.

Mahendra C, Murali M, Manasa G, Ponnamma P, Abhilash MR, Lakshmeesha TR, et al. Antibacterial and antimitotic potential of bio-fabricated zinc oxide nanoparticles of Cochlospermum religiosum (L.). Microb Pathog. 2017;110:620–9.

Goud PSP, Murthy KSR, Pullaiah T, Babu GV. Screening for antibacterial and antifungal activity of some medicinal plants of Nallamalais, Andhra Pradesh, India. J Econ Taxon Bot. 2005;29:704–8.

Kim YS, Kim J, Kim KM, Jung DH, Choi S, Kim CS, et al. Myricetin inhibits advanced glycation end product (AGE)-induced migration of retinal pericytes through phosphorylation of ERK1/2, FAK-1, and paxillin in vitro and in vivo. Biochem Pharmacol. 2015;93:496–505.

Jyothi Y, Sangeetha D. Cochlospermum religiosum (Linn): a phytopharmacological review. Res J Pharm Biol Chem Sci. 2016;7:277–82.

Stefek M. Natural flavonoids as potential multifunctional agents in prevention of diabetic cataract. Interdiscip Toxicol. 2011;4:69–77.

Devi VG, Rooban BN, Sasikala V, Sahasranamam V, Abraham A. Isorhamnetin-3-glucoside alleviates oxidative stress and opacification in selenite cataract in vitro. Toxicol In Vitro. 2010;24:1662–9.

Safari VZ, Ngugi MP, Orinda J, Njagi EM. Antipyretic, anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities of aqueous stem extract of Cynachum viminale (L.) in albino mice. Med Aromat Plants. 2016;5:1–7.

Nisa S, Bibi Y, Waheed A, Zia M, Sarwar S, Ahmed S, Chaudhary MF. Evaluation of anticancer activity of Debregeasia salicifolia extract against estrogen receptor positive cell line. Afr J Biotechnol. 2011;10:990–5.

Shamran DJ, Mahmmod MR, Manshood MA. Investigation of Cytotoxic effects of Dichanthium annulatum F. and Paspalum distichum L. on cell line SR. (Lymphoma) and L20B (Murine fibroblast). J Univ Babylon. 2018;26:184–90.

Fatima I, Kanwal S, Mahmood T. Evaluation of biological potential of selected species of family Poaceae from Bahawalpur, Pakistan. BMC Complementary Altern Med. 2018;18:27.

Thrikawala VS, Deraniyagala SA, Dilanka Fernando C, Udukala DN. In vitro α-amylase and protein glycation inhibitory activity of the aqueous extract of Flueggea leucopyrus Willd. J Chem. 2018;2787138. .

Soysa P, De Silva IS, Wijayabandara J. Evaluation of antioxidant and antiproliferative activity of Flueggea leucopyrus Willd (katupila). BMC Complem Altern M. 2014;274. .

Usnale SV, Biyani KR. Preclinical aphrodisiac investigation of ethanol extract of Flueggea leucopyrus Willd. leaves. J Phytopharmacol. 2018;7:319–24.

Shen T, Chen XM, Harder B, Long M, Wang XN, Lou HX, et al. Plant extracts of the family Lauraceae: a potential resource for chemopreventive agents that activate the nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2/antioxidant response element pathway. Planta Med. 2014;80:426–34.

Arfan M, Amin H, Kosinska A, Karamac M, Amarowicz R. Antioxidant activity of phenolic fractions of Litsea monopetala [Persimon-leaved Litsea] bark extract. Pol J Food Nutr Sci. 2008;58:229–33.

Choudhury D, Ghosal M, Das AP, Mandal P. In vitro antioxidant activity of methanolic leaves and barks extracts of four Litsea plants. Asian J Plant Sci Res. 2013;3:99–107.

Yusufoglu HS, Soliman GA, Foudah AI, Abdulkader MS, Ansari MN, Alam A, et al. 2018. Protective role of aerial parts of Silene villosa alcoholic extract against CCl4-induced cardiac and renal toxicity in rats. Int J Pharmacol. 2018;14:1001–9.

Iqbal T, Khan MG, Zaman T, Ullah F, Ahmad W, Aamir I. The study of elemental profile of some important medicinal plants collected from distract Karak, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Int J Chem Pharm Sci. 2014;5:69–74.

Ghonime M, Emara M, Shawky R, Soliman H, El-Domany R, Abdelaziz A. Immunomodulation of RAW 264.7 murine macrophage functions and antioxidant activities of 11 plant extracts. Immunol Invest. 2015;44:237–52.

Paszkowski WL, Kremer RJ. Biological activity and tentative identification of flavonoid components in velvet leaf (Abutilon theophrasti Medik.) seed coats. J Chem Ecol. 1988;14:1573–82.

Soberón JR, Sgariglia MA, Pastoriza AC, Soruco EM, Jäger SN, Labadie GR, et al. Antifungal activity and cytotoxicity of extracts and triterpenoid saponins obtained from the aerial parts of Anagallis arvensis L. J Ethnopharmacol. 2017;203:233–40.

Amoros M, Fauconnier B, Girre RL. In vitro antiviral activity of a saponin from Anagallis arvensis, Primulaceae, against herpes simplex virus and poliovirus. Antiviral Res. 1987;8:13–25.

Amoros M, Fauconnier B, Girre RL. Effect of saponins from Anagallis arvensis on experimental herpes simplex keratitis in rabbits. Planta Med. 1988;54:128–31.

Kreutzmann H, ed. Pastoral practices in High Asia. Agency of 'development' effected by modernisation, resettlement and transformation. Dordrecht: Springer; 2012. .

Mirani AH, Akhtar N, Shah MG, Memon AA, Jatoi AS. Documentation of ethnoveterinary plants for the treatment of different cattle and buffalo ailments in Tharparker, Sindh, Pakistan. 2016. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305568066_Documentation_of_Ethnoveterinary_Plants_for_the_Treatment_of_Different_Cattle_and_Buffalo_Ailments_in_Tharparker_Sindh_Pakistan. (Accessed 13 April 2020).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The study was partially funded by the University of Gastronomic Sciences, Pollenzo, Italy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MAA designed the project. MAA and AHK compiled and tabulated the primary data. MAA analysed the data and conducted the cross-cultural and cross-regional comparisons. MAA and AP drafted the manuscript and designed the conceptual discussion of the main outcomes. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S2

. Medicinal plants used in ethnoveterinary practices in Pakistan.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Aziz, M.A., Khan, A.H. & Pieroni, A. Ethnoveterinary plants of Pakistan: a review. J Ethnobiology Ethnomedicine 16, 25 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-020-00369-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-020-00369-1