Abstract

Dilute sulfuric acid pretreatment of the Jatropha curcas fruit hull at high temperatures (140°C to 180°C) performed in a 110-mL stainless steel reactor was investigated to enhance the enzymatic digestibility of its lignocellulosic components. Carbohydrates accounted for 43% of the dry matter of the J. curcas fruit hull biomass. The goal of the study was to optimize the pretreatment conditions (acid concentration, time, and temperature) in order to obtain the highest sugar yield after subsequent enzymatic hydrolysis. A Box-Behnken design was applied to the experimental setup in order to reduce the number of experiments. The optimal pretreatment conditions are 30-min incubations at a temperature of 178°C with a sulfuric acid concentration of 0.9% (w/v). Using these pretreatment conditions for a fruit solid loading of 9.52% followed by a 24-h enzymatic hydrolysis resulted in a liberation of 100% of all pentoses present (71% yield and 29% degradation to furfural) and 83% of the hexoses (78% yield and 5% degradation to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural). The simultaneous saccharification and fermentation experiment showed that acid-pretreated fruit hull can be used as a substrate for Saccharomyces cerevisiae to produce ethanol.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Jatropha curcas has become widely known as a biofuel crop due to the high oil content of the oilseeds harvested from this plant [1]. The biodiesel produced from J. curcas oil via transesterification compares well to petrochemical diesel and meets the latest biodiesel standards [2]. However, whereas palm oil is widely used as feedstock for biodiesel production in Indonesia, Jatropha oil has not been traded at price levels that satisfactorily reward growers/farmers. Low oil productivity and high labor cost for fruit harvesting are the most important reasons. Many potential Indonesian farmers in the subsistence sector are now reluctant to invest time and money in planting J. curcas since the profit from Jatropha products is much less compared to other agricultural commodities. Hence, one of the strategies to improve the economics of this potentially profitable plant is to increase the value of the side streams of oil production (trimmed stems/branches, seed or kernel cake, seed shells, and fruit hulls).

J. curcas bears fruit from the second year after crop establishment, but seed production becomes economically feasible from the fifth year onward [3, 4]. In Indonesia, J. curcas is planted at a 2 × 2-m distance, yielding 2,500 plants/ha. A productivity of 2 kg seeds/plant/year on a J. curcas plantation in Indonesia has been reported [5]. One hectare of the Jatropha plant therefore would yield 5 tons of seeds annually (containing 25% to 33% oil), with 1 ton/year of fruit hull biomass (dry weight) as side stream. Fruit hull is composed of lignocellulose (39.3% cellulose and 14.2% lignin) with 5.3% protein [4], making this biomass a potential raw material for the production of bioethanol, enzymes, organic acids, and other fermentative products, or as animal feed [6, 7]. The use of fruit hulls so far focuses on applications such as fertilizer and substrate for co-firing installations or for biogas production [1, 3, 4, 8]. Another way to valorize the fruit hull side stream is to convert it to fermentation products such as ethanol and lactic acid. In that case, pretreatment is required to enhance the enzymatic digestibility of the lignocellulosic biomass. Pretreatment aims at a partial dislocation of the inter- and intra-fibrillic structure of lignocellulose with a reasonable energy input [9]. From an economic point of view, pretreatment must improve fermentable sugar yield, maintain carbohydrate content, minimize formation of degradation products that are inhibitory to subsequent fermentation processes, and be cost-effective [10]. Various methods, from physical to chemical pretreatments or combinations, have been widely studied; one of which is hot dilute sulfuric acid pretreatment. Dilute acid pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass conducted at high temperature (more than 160°C) results in high xylan conversion yields and low levels of sugar degradation, thus resulting in an improved overall cellulose hydrolysis [10]. There are no reports on pretreatment of the fruit hull of J. curcas yet.

The subject of this study is the pretreatment of the Jatropha fruit hull by sulfuric acid at an elevated temperature in order to improve the enzymatic digestibility of this lignocellulosic byproduct. We study the influence of varying sulfuric acid concentration, pretreatment time, and temperature on the following three factors:

-

1.

Pentose and hexose degradations after fruit hull pretreatment, calculated from furfural and 5-HMF formed, respectively

-

2.

Pentose and hexose yields after subsequent enzymatic hydrolysis of the pretreated fruit hull

-

3.

Total sugar yield after subsequent enzymatic hydrolysis of the pretreated fruit hull

A Box-Behnken design was applied to the experimental setup in order to reduce the number of experiments. The main objective is to obtain an optimum sulfuric acid concentration, time, and temperature of pretreatment that give a low level of sugar degradation and a high level of sugar yield in the subsequent enzymatic hydrolysis. Simultaneous saccharification and fermentation (SSF) of J. curcas fruit hull hydrolysates by Saccharomyces cerevisiae for ethanol production is also studied.

Methods

Experimental design and setup

Design-Expert 8.0.3 software (Stat-Ease, Inc., MN, USA) was used for the experimental design, model fitting, and statistical data analysis. In order to reduce the number of experiments, a Box-Behnken design (BBD) [11] was applied. Experimental data of each response factor (Y) were expressed in a second order mathematical model:

where i = 1 to 3, j = 2 to 3, and X = input variables. The number of runs (N) required to measure the responses in BBD is defined as N = 2k(k − 1) + C o , where k is the number of input variables and C o is the number of central points. Since there were three input variables tested (sulfuric acid concentration, time of pretreatment, and temperature) and four replicates in the central point of the design to calculate the experimental error, a total of 16 experimental runs were carried out. The response factors are pentose degradation, hexose degradation, pentose yield, hexose yield, sugar degradation, and sugar yield. The significant effects and two variable interactions were estimated by ANOVA. The relationship between the response factor and input variables was further elucidated using response surface plots.

Materials

All chemicals were of analytical grade and used as received. Termamyl and amyloglucosidase were purchased from Novo Nordisk, Bagsvaerd, Denmark. Cellulase of GC220 was purchased from Genencor, Rochester, NY, USA. S. cerevisiae CBS 8066, maintained on YPD agar medium, was used for ethanol fermentation.

Preparation and analysis of fruit hull

Ripened J. curcas fruits (with yellow color only, harvested in November 2009, Serpong, Indonesia), were peeled. The hulls were collected and dried at 60°C for 48 h. The dried hulls were milled in a home blender (Philips HR 2071, Royal Philips Electronics, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and sieved through a strainer with a 0.8-mm hole diameter. The dry matter of the milled hull was 95.32% (w/w) (24 h, 105°C). The milled hull material was kept in a sealed plastic container at 4°C until used.

The chemical composition of the hull (Table 1) was analyzed in triplicate according to the following methods. The organic solvent extractives, the total water extractives, and the non-extractives (except protein) were measured by TAPPI methods [12–17], with minor modifications as described previously [18]. The protein content of the fruit hull was determined using the Kjeldahl method, which consists of a destruction unit (Gerhardt Kjeldahlterm) and distillation unit (Gerhardt Vapodest). The amounts of amino acids in the water extractives were determined using a Dionex Ultra-HPLC instrument (Dionex Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) as described previously [19]. For measuring monomeric sugars and water-soluble oligosaccharides in the fruit hull, the samples were prepared as shown in Figure 1. Monomeric sugars were measured by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD) as described earlier [18].

A scheme for determination of water-soluble sugars in fruit hull. A Hermle Z33M2 (HERMLE Labortechnik GmbH, Wehingen, Germany) was used in centrifugation. The amount of soluble oligosaccharides in the fruit hull was calculated by subtracting the initial monosaccharide present in the fruit hull from the total soluble sugar measured after enzymatic digestion.

Fruit hull pretreatment

Milled fruit hull (5.00 g; 4.76 g dry matter) was mixed with 45.0 mL of sulfuric acid solution (0.1%, 0.5% or 0.9% (w/v)), resulting in 9.52% (w/w) dry hull solid loading. The hull/acid mixture was soaked for 20 to 24 h at room temperature and then transferred to a 316-SS (stainless steel) reactor (inner height × diameter, 90.0 × 40.0 mm; 5.0-mm wall), fitted with thermocouples. Four reactors were heated at a time in an oil bath (Haake B bath filled with silicon oil of DC 200 fluid, 100 cSt, Dow Corning, Midland, MI, USA), equipped with a Haake N3 temperature controller (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Sample core temperature was digitally recorded using a Picotech data collector and software (Picotech, Neots, Cambridgeshire, UK). Pretreatments were conducted at 140°C, 160°C, and 180°C. Holding time was 30, 45, or 60 min, starting from when the desired core temperature was reached. The heating bath oil was preheated between 1°C and 5°C above the desired sample core temperature; by this way, the time until the desired core temperature was reached ranged between 16 and 20 min. During the holding time, the reaction temperature in the reactors oscillated at a maximum of 1°C from the desired temperature. The reactors were cooled after the incubation to 25°C in less than 10 min by quenching in ice water. After the pretreatment, the resulting material was transferred to pre-weighed 250-mL baffled shake flasks. The pH was adjusted to 5.0 with 10 M NaOH, and sodium azide solution (0.025% (w/w) final concentration; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) was added. A 1-mL sample was taken for analysis. Monomeric sugars were measured by HPAEC-PAD method [18]. Furfural, 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (5-HMF), and acetic acid were measured by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [18]. The monomeric sugar yield was calculated as follows:

where SL is the amount of sugar (g) in the aqueous phase, and SS is the amount of monomeric sugar present in the sample of dry hull (g sugar equivalents in polymeric sugar). The sugar degradation was calculated in a similar way in which SL is accounted as the amount of sugar equivalents (g) to the amount of furfural or 5-HMF present in the aqueous phase, calculated in mole basis.

Enzymatic hydrolysis of pretreated fruit hull

To start enzymatic hydrolysis, GC220 (0.4 g (w/w) dry matter hull) was added into the baffled shake flask containing the pH-adjusted (pH 5.0) pretreated fruit hull. GC220 is a cellulase enzyme mixture (batch 4900759148, 7608 IU/mL cellulase activity). The amount of GC220 used corresponded to 46 FPU/g original dry matter hull. We used GC220 in excess (in the plateau region of the dose-effect curve of the enzyme mixture) to ensure that the effect of pretreatment on the sugar yield was measured, not the effect of the enzyme concentration. The weight of the material plus the flask was determined; after which, the flasks were closed with airtight plugs and placed in an Innova 44 incubator shaker (50°C, 150 rpm, 2-in. stroke; NBSC, NJ, USA). Samples of 1.5 mL were taken at t = 0, 24, and 72 h. GC220 was inactivated by incubation at 90°C for 10 min. Samples were stored at −20°C until analysis. Monomeric sugars were measured by HPAEC-PAD method [18].

SSF of acid-pretreated hull hydrolysate into ethanol

Ten grams of milled fruit hull pretreated with 90 mL of sulfuric acid solution at the optimum conditions was used for ethanol fermentation tests with the yeast S. cerevisiae CBS 8066.

To prepare inoculums, yeast cells were grown in a 100-mL liquid medium of YPD (Merck) at pH 5.0 in a 250-mL Erlenmeyer flask. The culture was incubated for 24 h in an Innova 44 incubator shaker (37°C, 150 rpm, 2-in. stroke; NBSC, NJ, USA). The yeast cake was prepared by centrifugation at 17,000 × g for 15 min using the SORVALL RC6+ centrifuge (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Prior to fermentation, the pH of the acid-pretreated hull was adjusted to 5.0 using 10 M NaOH. Pre-hydrolysis was conducted to reduce the viscosity of the pretreated hull suspension and was performed by the addition of 0.95 g GC220 (equivalent to 0.1 g/g dry matter hull) followed by incubation for 6 h in an Innova 44 incubator shaker (37°C, 150 rpm, 2-in. stroke; NBSC, NJ, USA). After pre-hydrolysis, the pre-hydrolysed substrate was enriched with the following (per liter): 4.2 g (NH4)2SO4, 2.5 g KH2PO4, 0.42 g MgSO4·7H2O, trace elements (consisting of 15.0 mg Na2EDTA, 4.5 mg ZnSO4·2H2O, 0.84 mg MnCl2·2H2O, 0.3 mg CoCl2·6H2O, 0.3 mg CuSO4·5H2O, 0.4 mg Na2MoO4·2H2O, 4.5 mg CaCl2·2H2O, 3 mg FeSO4·7H2O, 1 mg H3BO3, 1 mg KI, 0.05), vitamins (consisting of 0.05 mg biotin, 1.0 mg calcium panthotenate, 1.0 mg nicotinic acid, 25 mg inositol, 1.0 mg thiamine, 1.0 mg pyridoxine HCl, 0.2 mg para-aminobenzoic acid), and fatty acids (10.0 mg ergosterol and 420 mg Tween 80 dissolved in 1.25 mL ethanol). Trace element solution, vitamin solution, and fatty acid solution were prepared separately in stocks of 1,000×, 1,000×, and 800×, respectively, as described previously [20]. A 2.86-g enzyme mixture (GC220), equivalent to 0.3 g/g dry matter hull, was added to the substrate. The total volume of the substrate just before fermentation was circa 100 mL. An initial yeast cake concentration between 0.50 and 0.55 g/100-mL substrate was applied in the SSF experiments [21]. Fermentation was conducted at 37°C and 70 rpm for 72 h. All SSF experiments were done in duplicate, and homogenous samples of 1.5 mL were withdrawn at 0 (just after yeast addition), 6, 11, 24, 35, 48, and 72 h of incubation for the analysis of monosaccharides, organic acids, and ethanol. For the analysis of ethanol and organic acids in SSF samples, the supernatant of centrifuged samples (5 min at 17,400 × g) was diluted 1:1 with 6 mM sulfuric acid and filtered in order to remove solids and precipitated proteins. Samples were analyzed using a HPLC system (Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA) using the organic acid column IOA-1000 (Alltech, Deerfield, IL, USA) with 3.0 mM sulfuric acid as the mobile phase at 90°C and a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. Peaks were detected by using a RI detector (Waters 2414, Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA). SSF results of sugars, organic acids, and ethanol were reported in grams of product formed per liter fermentation medium. The theoretical ethanol yield was calculated from the total glucose consumed by the yeast, taking into account a fermentation yield of 0.51 [21, 22].

Results and discussion

Raw material composition

Table 1 shows the composition of the J. curcas fruit hull. Carbohydrates account for 42.9% of the dry weight. This value is lower than those reported for other lignocellulosic materials such as wheat straw (59%) and cardoon biomass (52%) [22, 23]. A glucan (as glucose) content of 31.6% is comparable to those reported for agricultural residues such as cardoon, sunflower, or Brassica[22, 24, 25] but slightly lower than those for wheat straw and rice straw (36%) [18, 26]. Unlike wood and straw, the hull contains about 12% water-soluble sugars. The total lignin value is 12.5% of which acid-soluble lignin (ASL) accounts for 0.8% only. The lignin value of the hull is less than 50% of that of wood [27, 28]. ASL will solubilize during acid pretreatment, while acid-insoluble lignin remains in solid form. Hemicellulosic sugars (xylose, galactose, mannose, rhamnose, and arabinose) account for 10.4% of the hull with xylose (5.7%) as the main hemicellulosic carbohydrate. No xylose was found after incubation of the water-extractable fraction with the enzyme mixture GC220 (data not shown), indicating that the material does not contain soluble xylan. Together, the organic solvent extractables and water extractables account for 30% of the total dry matter, which may include nonstructural components of fruit hulls such as waxes, fats, tannins, some resins, and soluble pectins [28, 29]. In comparison, the values for glucan and lignin content obtained are lower than those of the J. curcas fruit hull (39.3% and 14.2%, respectively) previously reported [4], which could be due to differences in cultivar, cultivation conditions, or ripeness of the fruit.

Pretreatment and enzymatic hydrolysis of fruit hull

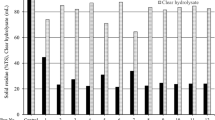

The experimental conditions for the 16 runs according to the BBD can be seen in Table 2. Table 2 also summarizes the overall experimental results of sugar liberation from milled Jatropha fruit hull after pretreatment and subsequent enzymatic hydrolysis for 24 h.

Both the highest pentose yield (34.4%) and pentose degradation (42.4%) after pretreatment were achieved at 0.9% sulfuric acid, 45 min, and 180°C, in which 57.4% pentose and 80.6% hexose were recovered after subsequent enzymatic hydrolysis (Table 2). After the subsequent 24-h enzymatic hydrolysis, the highest pentose yield (84.7%) was obtained from the biomass pretreated at less severe conditions (0.9% sulfuric acid, 30 min, and 160°C) in comparison to the highest hexose yield (80.6%) which was obtained at more severe conditions (0.9% sulfuric acid, 45 min, and 180°C).

In terms of total sugar liberation (Table 2), both the highest sugar yield (21.0%) and sugar degradation (24.4%) after pretreatment were achieved at 0.9% sulfuric acid, after 45 min, and at 180°C. After the subsequent 24-h enzymatic hydrolysis, the highest sugar yield of 77.0% was reached at this pretreatment condition.

Statistical analysis of sugar degradation and sugar yield

In the experimental Box-Behnken design, the influence of the three input variables (sulfuric acid concentration, time, and temperature of pretreatment) on pentose degradation, hexose degradation, pentose yield, and hexose yield were determined. The Box-Behnken model used to describe the experimental results is based on the effect of the three input variables studied, extended with parameters for interactions and squared factors. A square root transformation of the response factors was applied for improved model fit. To describe the interactive effects of the input variables on responses in the statistical analysis, one variable is set constant while the other two variables are varying in the design space. The input variables of X1, X2, and X3 are the coded factors of sulfuric acid concentration, time, and temperature of pretreatment, respectively. The coded variables are defined as follows: X1 = (SA − SA,C)/SA,S, X2 = (t − tC)/tS, and X3 = (T − TC)/TS, in which SA = concentration of sulfuric acid (%), t = pretreatment time (min), and T = pretreatment temperature (°C); subscript C = center value and subscript S = step value; SA,C = 0.5%, SA,S = 0.4%, tC = 45 min, and tS = 15 min, TC = 160°C and TS = 20°C.

Pentose and hexose degradation after pretreatment

The starting point was a quadratic model which was found significant for the degradation of pentose into furfural and the degradation of hexose into 5-HMF during the pretreatment (both with P < 0.0001). The quadratic model was then adjusted by backward elimination: taking out terms that had no significant contribution (P > 0.05) one by one and then recalculating the model with the remaining terms. The adjusted regression models fit the data with the Radjusted2 of 0.99 for pentose degradation (Equation 3) and 0.97 for hexose degradation (Equation 4) as follows:

in which YPD,Pr (% w/w) is the pentose degradation, and YHD,Pr (% w/w) is the hexose degradation after pretreatment, respectively.

Figure 2 shows the response curves of pentose and hexose degradation as three-dimensional surfaces. As can be seen in Figure 2a and Equation 3, minimizing the degradation of pentose into furfural depends, for a large part, on sulfuric acid concentration and temperature. Degradation of pentose increases rapidly at higher sulfuric acid concentration and temperature. Because the degradation of pentose is, for a small part, influenced also by time, conducting the pretreatment step in a shorter time (30 min) is preferable than a longer pretreatment time if high pentose recovery is the target. A pentose degradation of 34% is obtained at 30 min, 0.9% sulfuric acid, and 180°C (Figure 2a) in which 33% of the pentose is simultaneously recovered (data not shown), resulting in a total pentose liberation from the biomass of 67%. A corresponding result has been reported in the pretreatment of corn stover at 20% (w/w) solid loading by using sulfuric acid (0.5% to 1.4% (w/w)) at 165°C to 195°C for 3 to 12 min, in which pentose degradation ranged between 5% and 31% [30].

In case of hexose degradation, from the three input variables studied, the pretreatment time has no significant contribution on the degradation of hexose (Equation 4). The influence of the sulfuric acid concentration and temperature causes less than 6% hexose degradation in the design space as shown in Figure 2b. The low hexose degradation at pretreatment demonstrates that only a small fraction of the six-carbon polysaccharides (mostly cellulose) of the biomass was completely depolymerized and degraded during the pretreatment, a positive property of a pretreatment, assuming the treatment's ability to facilitate the subsequent enzymatic hydrolysis.

Pentose and hexose yields after enzymatic hydrolysis

The starting point was a quadratic model which was found significant for the pentose yield and the hexose yield after the subsequent 24-h enzymatic hydrolysis of pretreated fruit hulls (both with P < 0.0001). The quadratic model was then adjusted by backward elimination: taking out terms that had no significant contribution (P > 0.05) one by one and then recalculating the model with the remaining terms. The adjusted regression models fit the data with the Radjusted2 of 0.91 for pentose yield (Equation 5) and 0.99 for hexose yield (Equation 6) as follows:

in which YPY,24h (% w/w) is the pentose yield, and YHY,24h (% w/w) is the hexose yield after the 24-h enzymatic hydrolysis, respectively. Figure 3 shows the response analysis of pentose and hexose yields as three-dimensional surfaces.

As can be seen in Figure 3a and Equation 5, maximizing the pentose yield is, for a large part, dependent on sulfuric acid concentration and temperature. The time of pretreatment on its own has no direct significant contribution on the pentose yield, but its interaction with the temperature has. In comparison to our results, it was reported that the yield of xylose (a major component of pentose) after a dilute sulfuric acid (0.5% to 2%) pretreatment of rapeseed straw at high temperature (180°C) is dependent on acid concentration and time of pretreatment [31].

Figure 3 shows that pretreatment of the fruit hull at the conditions studied results in a significant increase of the pentose yield and the hexose yield in the hydrolysis step. Approximately 84% pentose yield after enzymatic hydrolysis can be achieved at 0.9% sulfuric acid (30-min pretreatment at 160°C) in which approximately 10% pentose is degraded (Figure 2a). Increasing the temperature above 160°C or the time of pretreatment for more than 30 min (data not shown) does not improve the pentose yield due to the degradation of pentose into furfural. The 30-min pretreatment results in a higher pentose yield than the longer pretreatment periods.

We found that without enzymatic hydrolysis, pretreatment alone of the fruit hull with 0.1% sulfuric acid at a temperature between 140°C and 180°C resulted in pentose yields of less than 4% (data not shown). However, high overall pentose yields obtained after enzymatic hydrolysis of the fruit hull pretreated with 0.1% sulfuric acid at 140°C to 180°C (Figure 3a) demonstrate that the hydrothermal treatment itself contributes to hemicellulose digestibility, thereby enhancing the enzymatic hydrolysis. It has been reported that heating lignocellulosic biomass in aqueous media at a temperature above 150°C to 180°C will solubilize parts of the biomass, firstly the hemicellulose and shortly after the lignin [32].

From Figure 3b and Equation 6, the hexose yield ranged from approximately 52% at the least severe pretreatment (0.1% sulfuric acid, 30 min, 140°C) to approximately 78% at the more severe conditions (0.9% sulfuric acid, 30 min, 180°C).

Total sugar yield after enzymatic hydrolysis

For the total sugar degradations (pentose plus hexose degradation) after pretreatment and the total sugar yield (pentose plus hexose yield) after the subsequent 24-h enzymatic hydrolysis of the pretreated fruit hull, the starting point of a quadratic model was found significant (P < 0.0001). The quadratic model was then adjusted by backward elimination: taking out terms that had no significant contribution (P > 0.05) one by one and then recalculating the model with the remaining terms. The adjusted regression models fit the data with the Radjusted2 of 0.98 for the total sugar degradation (Equation 7) and 0.96 for the total sugar yield (Equation 8) as follows:

in which YSD,Pr (% w/w) is the total sugar degradation after pretreatment, and YSY,24h (% w/w) is the total sugar yield after the subsequent 24-h enzymatic hydrolysis.

Figure 4 shows the response curve of the total sugar yield and the total sugar degradation as three-dimensional surfaces. Statistical analysis of combined sugars (pentose plus hexose) showed that the time of pretreatment has no influence on the total sugar yield (Equation 8). Sulfuric acid concentration and temperature as well as their interaction have positive influences on the total sugar yield, to the increase of overall sugar yield as sulfuric acid concentration and temperature increase. Because of the negative squared term of the temperature (Equation 8), an optimum point somewhere in the experimental space might be expected; however, the temperature coefficient seems too small to level off the curve. A yield of 78% was the maximum achieved value at the temperature of 180°C using 0.9% sulfuric acid, in which 21% sugar is degraded into furfural and 5-HMF (Figure 3).

Three-dimensional response surfaces for total sugar degradation (dark) and total sugar yield (light). The response surface for total sugar degradation was graphed after pretreatment, and that for total sugar yield was graphed after the 24-h enzymatic hydrolysis of the pretreated J. curcas fruit hull. Pretreatment time is 30 min.

Optimization and confirmation test

It has been shown that the maximum sugar yield as well as the hexose yield, respectively, after enzymatic hydrolysis can be achieved only if pretreatment of the fruit hull (9.52% solid loading) was performed using 0.9% sulfuric acid at a temperature around 180°C. Using the Design-Expert 8.0.3 software, optimization was conducted to obtain the highest hexose/sugar yields with minimum sugar degradations. The optimal conditions were as follows: sulfuric acid equals 0.9%; time equals 30 min, and temperature equals 178°C. Under these conditions, the model predicts the responses as follows: pentose degradation of 31%, hexose degradation of 6%, a pentose yield (after 24-h enzymatic hydrolysis) of 72%, and a hexose yield (after 24-h enzymatic hydrolysis) of 77%.

A confirmation test was performed under the pretreatment conditions described above, in duplicate. The experimental results with the deviations from the average were as follows: pentose degradation of 29.4 ± 1.27% (equivalent to 1.5 ± 0.05 g/L furfural), hexose degradation of 5.2 ± 0.14% (equivalent to 1.2 ± 0.03 g/L 5-HMF), a pentose yield of 70.8 ± 1.20% (equivalent to 4.4 ± 0.08 g/L pentose), and a hexose yield (24 h) of 78.3 ± 0.70% (equivalent to 26.5 ± 0.25 g/L hexose). These experimental sugar values agree well to those predicted by the model with deviations less than 1%. In addition, we found that acetic acid liberation was 1.5 ± 0.02 g/L.

SSF of hydrolysed fruit hull into ethanol

Fruit hull of 9.52% solid loading pretreated at optimum conditions (0.9% sulfuric acid, 178°C, 30 min) was applied in a SSF process using S. cerevisiae at 37°C. In a SSF process, the glucose liberated by enzymatic hydrolysis is simultaneously converted into ethanol, thus reducing product inhibition of the enzyme by glucose. Figure 5 shows the course of ethanol formation for the 72-h fermentation in the standard medium containing 30 g/L glucose (Figure 5a) in comparison to the medium containing the pretreated fruit hull (Figure 5b).

Course of ethanol formation. Formation of ethanol, liberation of acetic acid, and the consumption trends of glucose and xylose during fermentation by S. cerevisiae CBS 8066 of (a) standard medium containing glucose as a sole carbon source in comparison to (b) SSF of the pretreated J. cu rcas fruit hull.

In the standard medium, glucose is depleted within 12 h. In that period, ethanol was rapidly produced and peaked at about 10.7 g/L. This ethanol concentration corresponds to 74% of the maximum theoretical yield.

In the pretreated fruit hull medium (Figure 5b), a 6-h pre-hydrolysis to reduce the viscosity of the hydrolysate suspension resulted in 18 g/L glucose initially available in the medium before the fermentation started. As can be seen in Figure 5b, glucose depletion in the fruit hull medium was slower than in the standard medium, reaching 2 g/L after 36 h and remaining constant from that point; the maximum ethanol concentration was 8.4 g/L at 24 h (corresponding to 71% of the maximum theoretical yield). This trend of ethanol formation, peaking at 24 h, corresponds well to the results previously reported [21]. It is clearly seen that ethanol formation was slightly inhibited in the pretreated fruit hull biomass, leading to a lower ethanol yield (71% compared to 74%) and longer fermentation time (24 h compared to 12 h) at peak points. In biomass hydrolysis, limiting concentrations of byproducts are important when the hydrolysate is to be used as a fermentation medium. For ethanol fermentation, it was reported that the presence of acetic acid (5 g/L), furfural (1.2 g/L), and 5-HMF (1.3 g/L) slightly decreased the ethanol yield in the fermentation process; however, a low acetic acid concentration (about 1 g/L) was found to have a positive effect on the ethanol production yield [33]. Due to pretreatment of the fruit hull at optimum conditions, 1.5 g/L furfural, 1.2 g/L 5-HMF, and 1.5 g/L acetic acid were also formed in the fermentation substrate. Therefore, inhibition of ethanol formation in the fruit hull substrate was probably caused by the presence of these compounds.

Conclusions

It is demonstrated that the model equations developed using the Box-Behnken design with the three input variables studied (sulfuric acid, time, and temperature) can be used to predict liberation and degradation of sugars from the J. curcas fruit hull after dilute sulfuric acid-catalyzed hydrothermal pretreatment and subsequent enzymatic hydrolysis. A pretreatment at optimum conditions (0.9% sulfuric acid, 30 min, 178°C) followed by a 24-h enzymatic hydrolysis liberates nearly all of the sugars present, consisting of 71% pentose, 78% hexose, 29% pentose degradation into furfural, and 5% hexose degradation into 5-HMF. Therefore, higher sugar yields cannot be expected within the space studied. The SSF experiment of ethanol production showed that the sulfuric acid-pretreated fruit hull can be used to produce ethanol by S. cerevisiae in the simultaneous saccharification and fermentation process.

References

Gubitz GM, Mittelbach M, Trabi M: Exploitation of the tropical oil seed plant Jatropha curcas L. Bioresour Technol 1999, 67: 73–82. 10.1016/S0960-8524(99)00069-3

Tiwari AK, Kumar A, Raheman H: Biodiesel production from jatropha (Jatropha curcas) with high free fatty acids: an optimized process. Biomass Bioenergy 2007, 31: 569–575. 10.1016/j.biombioe.2007.03.003

Foidl N, Eder P: Agro-industrial exploitation of J. curcas. In Biofuels and Industrial Products from Jatropha curcas. Edited by: Gubitz GM, Mittelbach M, Trabi M. The Austrian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Managua, Nicaragua; 1997:88–91.

Gunaseelan VN: Biomass estimates, characteristics, biochemical methane potential, kinetics and energy flow from Jatropha curcus on dry lands. Biomass Bioenergy 2009, 33: 589–596. 10.1016/j.biombioe.2008.09.002

Purwaamijaya IM, Masri RM, Tukimin S: Social economic analysis of seeding and cultivation of Jatropha curcas, Linnaeus as alternative energy sources (bioediesel) which environmental friendly. Indonesia Education of University, Bandung; 2007.

Wyman CE: Ethanol from lignocellulosic biomass: technology, economics, and opportunities. Bioresour Technol 1994, 50: 3–15. 10.1016/0960-8524(94)90214-3

Gonzalez-Garcia S, Moreira MT, Feijoo G: Comparative environmental performance of lignocellulosic ethanol from different feedstocks. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 2010, 14: 2077–2085. 10.1016/j.rser.2010.03.035

Openshaw K: A review of Jatropha curcas: an oil plant of unfulfilled promise. Biomass Bioenerg 2000, 19: 1–15. 10.1016/S0961-9534(00)00019-2

Abatzoglou N, Bouchard J, Chornet E, Overend RP: Dilute acid depolymerization of cellulose in aqueous phase: experimental evidence of the significant presence of soluble oligomeric intermediates. Can J Chem Eng 1986, 64: 781–786. 10.1002/cjce.5450640510

Sun Y, Cheng JY: Hydrolysis of lignocellulosic materials for ethanol production: a review. Bioresour Technol 2002, 83: 1–11. 10.1016/S0960-8524(01)00212-7

Box GEP, Behnken DW: Simplex-sum designs: a class of 2nd order rotatable designs derivable from those of 1st order. Ann Math Stat 1960, 31: 838–864. 10.1214/aoms/1177705661

TAPPI: Test Method T 418 cm-97. Organic Nitrogen in Paper and Paperboard, TAPPI, Georgia; 2004.

TAPPI: Test Method T 211 om-02. Ash in Wood, Pulp, Paper and Paperboard: Combustion at 525°C, TAPPI, Georgia; 2004.

TAPPI: Test Method T 222 om-02. Acid-Insoluble Lignin in Wood and Pulp, TAPPI, Georgia; 2004.

TAPPI: Test Method T 249 cm-00. Carbohydrate Composition of Extractive-Free Wood and Wood Pulp by Gas–Liquid Chromatography, TAPPI, Georgia; 2004.

TAPPI: Test Method T 412 om-02. Moisture in Pulp, Paper and Paperboard, TAPPI, Georgia; 2004.

TAPPI: Test Method T 204 cm-97. Solvent Extractives of Wood and Pulp, TAPPI, Georgia; 2004.

Kootstra AMJ, Beeftink HH, Scott EL, Sanders JPM: Optimization of the dilute maleic acid pretreatment of wheat straw. Biotechnol Biofuel 2009, 2: 1–14. 10.1186/1754-6834-2-1

Teng YL, Scott EL, van Zeeland ANT, Sanders JPM: The use of l-lysine decarboxylase as a means to separate amino acids by electrodialysis. Green Chem 2011, 13: 624–630. 10.1039/c0gc00611d

Verduyn C, Postma E, Scheffers WA, Vandijken JP: Effect of benzoic acid on metabolic fluxes in yeasts: a continuous-culture study on the regulation of respiration and alcoholic fermentation. Yeast 1992, 8: 501–517. 10.1002/yea.320080703

Cuevas M, Sanchez S, Bravo V, Garcia JF, Baeza J, Parra C, Freer J: Determination of optimal pre-treatment conditions for ethanol production from olive-pruning debris by simultaneous saccharification and fermentation. Fuel 2010, 89: 2891–2896. 10.1016/j.fuel.2010.02.005

Ballesteros I, Ballesteros M, Manzanares P, Negro MJ, Oliva JM, Saez F: Dilute sulfuric acid pretreatment of cardoon for ethanol production. Biochem Eng J 2008, 42: 84–91. 10.1016/j.bej.2008.06.001

Kootstra AMJ, Beeftink HH, Scott EL, Sanders JPM: Comparison of dilute mineral and organic acid pretreatment for enzymatic hydrolysis of wheat straw. Biochem Eng J 2009, 46: 126–131. 10.1016/j.bej.2009.04.020

Ballesteros I, Oliva JM, Negro MJ, Manzanares P, Ballesteros M: Enzymic hydrolysis of steam exploded herbaceous agricultural waste (Brassica carinata) at different particule sizes. Process Biochem 2002, 38: 187–192. 10.1016/S0032-9592(02)00070-5

Ruiz E, Cara C, Ballesteros M, Manzanares P, Ballesteros I, Castro E: Ethanol production from pretreated olive tree wood and sunflower stalks by an SSF process. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2006, 130: 631–643. 10.1385/ABAB:130:1:631

Bak JS, Ko JK, Choi IG, Park YC, Seo JH, Kim KH: Fungal pretreatment of lignocellulose by Phanerochaete chrysosporium to produce ethanol from rice straw. Biotechnol Bioeng 2009, 104: 471–482. 10.1002/bit.22423

Yang B, Boussaid A, Mansfield SD, Gregg DJ, Saddler JN: Fast and efficient alkaline peroxide treatment to enhance the enzymatic digestibility of steam-exploded softwood substrates. Biotechnol Bioeng 2002, 77: 678–684. 10.1002/bit.10159

Cara C, Ruiz E, Ballesteros I, Negro MJ, Castro E: Enhanced enzymatic hydrolysis of olive tree wood by steam explosion and alkaline peroxide delignification. Process Biochem 2006, 41: 423–429. 10.1016/j.procbio.2005.07.007

Winkler E, Foidl N, Gubitz GM, Staubmann R, Steiner W: Enzyme-supported oil extraction from Jatropha curcas seeds. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 1997, 63–65: 449–456.

Schell DJ, Farmer J, Newman M, McMillan JD: Dilute-sulfuric acid pretreatment of corn stover in pilot-scale reactor:investigation of yields, kinetics, and enzymatic digestibilities of solids. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2003, 105: 69–85. 10.1385/ABAB:105:1-3:69

Lu XB, Zhang YM, Angelidaki I: Optimization of H2SO4-catalyzed hydrothermal pretreatment of rapeseed straw for bioconversion to ethanol: focusing on pretreatment at high solids content. Bioresour Technol 2009, 100: 3048–3053. 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.01.008

Hendriks A, Zeeman G: Pretreatments to enhance the digestibility of lignocellulosic biomass. Bioresour Technol 2009, 100: 10–18. 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.05.027

Erdei B, Barta Z, Sipos B, Reczey K, Galbe M, Zacchi G: Ethanol production from mixtures of wheat straw and wheat meal. Biotechnol Biofuel 2010, 3: 9. 10.1186/1754-6834-3-9

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, Scientific Programme Indonesia - Netherlands (SPIN-KNAW) for the financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

AM carried out the design of the study and laboratory experiments, performed statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. AMJK participated in the design of the study and involved in HPLC measurements. JPMS conceived the study and participated in its design. RAW participated in the design of the study and coordination. All authors read, edited, and eventually approved the final manuscript to be submitted.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Marasabessy, A., Kootstra, A.M.J., Sanders, J.P. et al. Dilute H2SO4-catalyzed hydrothermal pretreatment to enhance enzymatic digestibility of Jatropha curcas fruit hull for ethanol fermentation. Int J Energy Environ Eng 3, 15 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/2251-6832-3-15

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2251-6832-3-15