Abstract

Background

In the framework of periodic homogenization, the conduction problem can be formulated as an integral equation whose solution can be represented by a Neumann series. From the theory, many efficient numerical computation methods and analytical estimations have been proposed to compute the effective conductivity of composites.

Methods

We combine a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) numerical method based on the Neumann series and analytical estimation based on the integral equation to solve the problem. Specifically, the analytical approximation is used to estimate the remainder of the series.

Results

From some numerical examples, the coupling method have shown to improve significantly the original FFT iteration scheme and results are also superior to the analytical estimation.

Conclusions

We have proposed a new efficient computation method to determine the effective conductivity of composites. This method combines the advantages of the FFT numerical methods and the analytical estimation based on integral equation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Composite materials can exist in nature or be fabricated by purpose. Due to their technological importance, micromechanical approaches are developed to determine the overall behavior of composites from the properties of their constituents. The general procedure comprises two steps: the construction of a representative model, containing information on heterogeneities (morphologies, inclusion shape, volume fraction, local physical properties, etc.), and the analysis of the model by some mathematical methods. Analytical methods are often based on a simplification of inclusion shapes and potential theory, spherical harmonic functions, etc. Many exact and approximate closed-form solutions have been derived by such methods for materials having a linear behavior [1–7]. However, if the microstructure is known in all its complexity, numerical methods must be used. Among the numerical methods, finite element method (FEM) and boundary element method (BEM) are widely used for homogenization problems. These methods have been reported in numerous works [8–12]. A more recent method, introduced in the 1990s and described thereafter, uses extensively the Fourier transform and the introduction of a ‘reference material’.

From a theoretical point of view, the introduction of a reference material allows formulation of the localization problem in the form of a Lippman-Schwinger-Dyson-type integral equation, whose solution can be represented by a Neumann series. The most convenient way to solve this integral equation is its formulation using Fourier transform of the equations governing the localization problem [13–19]. Some notable variants and improvements of this method can be found in the literature [18, 20–23]. However, it is known that fast Fourier transform (FFT) iterative schemes are very sensitive to the contrast ratio between the phases and may not converge for infinite contrasts. Therefore, an important step when using FFT iterative schemes is to estimate the remainder of the Neumann series whose sum is computed up to a finite number of terms. This paper is devoted to this fundamental question.

In this paper, the remainder of the Neumann series is estimated by a combination between FFT schemes and the Nemat-Nasser-Iwakuma-Hejazi (NIH) [24, 25] estimation of the effective properties. For two-phase systems with spherical inclusions, the NIH estimation in thermal problems leads to closed-form solutions which agree with numerical results for a large range of volume fractions. However, the NIH estimation departs from the sum of the Neumann series at high concentrations of inclusions. Since both NIH approximation and FFT schemes are based on integral equations, we use the former to estimate analytically the remainder of the Neumann series and derive the improved effective properties.

The present paper contains four parts. After a brief introduction of the paper’s context, the ‘Methods’ Section is dedicated to the computational methods. The problem statement, FFT methods, and the FFT-NIH coupling are also presented in this section. Implementations of the coupling are discussed in the ‘Results and discussion’ Section. Finally, concluding remarks are given in the ‘Conclusions’ Section.

Methods

Problem statement and integral equation formulation

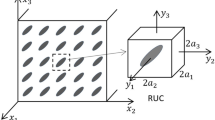

A periodic composite material is constructed by repeating infinitely a unit rectangular cell V of dimensions a1,a2,a3 along three directions x1,x2,x3. The homogenization of its thermal conductivity is reduced to solving the periodic heat transfer problem defined by the system of equations:

In (1), q(x) is the flux vector, T(x) the temperature, e(x) the (minus) temperature gradient, K(x) the local second-order conductivity, and n the outward normal vector on the surface of the unit cell. Solution of (1) allows computation of the volume averages of e and q, denoted, respectively, by E and Q and finally the overall conductivity Keff. In summary, we can write

Here and from now on, we use the angular brackets 〈.〉 V to denote the volume average over V, for example,

Instead of solving the system of (1), the integral equation approach reformulates the boundary value problem using a reference material with arbitrary conductivity K0. This allows the introduction of the free gradient e∗ through the following formula:

with

Since any V-periodic function ϕ can be represented by a Fourier series,

applying Fourier analysis to (1) and (4) yields an integral equation for e∗(x):

The Green tensor in (7), the Fourier representation of the periodic Green operator Γ0, is defined by the following formula:

The infinite sums in (6) and (7) involve all vectors ξ with components ξ i satisfying the conditions

Method of resolution

Full field solution of (1) and the effective properties can be determined by FFT-based methods at any accuracy. By recasting (7), a more convenient form is obtained [18, 26, 27]:

A classical way of solving the integral equation is to sum the Neumann series

under the condition that the Neumann series is convergent, which is achieved for a specific range of admissible values of K0. To solve (10), iterative schemes are usually employed. For example, starting from the initial value e0(x) = E, one can repeatedly compute e1,e2, …, eN via the recurrence relation

Stopping the recurrence at N0 iterations produces the sum of the N0 first terms in the Neumann series (11). It is worthwhile mentioning that relation

holds for all rotational free vector e and leads to another equivalent form of (12):

Although the FFT-based methods produce e(x) at convergence, the main concern is the convergence rate at high contrast ratio. The basic iterative scheme described in (12) and (14) is called the primal iterative scheme (PIS). In the literature, there have been numerous works to improve the convergence of the basic method such as dual iterative scheme (DIS) [20, 28], polarization-based iterative scheme (PBIS) [21, 22], accelerated scheme (AS) [18], augmented Lagrangian scheme (ALS) [16], etc.

Instead of finding the full field solution of (1), the mean value of e∗ and the effective thermal conductivity Keff can be estimated from (7) with NIH approximation [24, 25]. Such an approximation has been shown to predict very well the overall elastic and thermal properties of two-phase composites for a large range of volume fractions of inclusions [25, 29]. However, it fails at higher concentrations. Generally, the estimation of Keff requires only the computation of a lattice sum which admits closed-form expressions in many cases, as seen thereafter.

Residual integral equation and estimation of the remainder of the Neumann series

The main scope of this paper is to combine the advantages of the analytical approximation and FFT numerical methods to improve the prediction of the effective properties. The material under consideration is a two-phase matrix-inclusion composite with conductivity of both phases being KM (matrix) and KI (inclusion). The volume fraction of the inclusions is f, and the distribution of the inclusions in the unit cell is taken to be general at this stage.

Starting with any conventional FFT method (e.g., PIS, PBIS), we assume that after N iterations, we have obtained eN which is an estimation of the exact solution . In the coupled method, we consider the residual rN at step N defined by

Knowing the average of rN allows computation of the macroscopic flux associated to . Indeed, by averaging (15) over V and accounting for the following properties:

we can deduce that

When eN is computed from the primal iterative scheme, 〈eN〉 V = E is always true and Q∗ always vanishes (for other schemes, this quantity is known). The other terms QN and in (17), respectively, are the macroscopic flux calculated by the conventional FFT method and the real flux. They are different by a correcting term f〈rN〉 Ω which will be estimated through the NIH approach. Substituting (15) into (10) with the matrix as the reference material and accounting for (12), we obtain the following integral equation for rN:

in which wN is known from the expressions

Since the convolution ΓM∗rN admits the Fourier representation

averaging both sides of (18) over the inclusion Ω yields

Next, the NIH approximation is applied to as follows:

By denoting I(ξ), P(ξ) the following shape functions:

we can now obtain the average of the residual term 〈rN〉 Ω through the new relation

Substituting (24) back into (17), we obtain , an improved estimation of the macroscopic flux . It is noteworthy that if we apply the property at convergence (13) to eN in (19), the term ε-eN can be computed from the expression

The method presented in this paper can be used in coupling with any FFT-based iterative scheme. An algorithm presenting the implementation with the basic scheme (PIS) is presented in Algorithm 1 and used later in this work. In the following, this scheme will be stopped before convergence, in view to evaluate the performance of the estimation of the remainder of the series.

Algorithm 1 Algorithm of the iterative scheme PIS coupled with NIH approximation

Although the original NIH estimation is obtained by making approximation to (7) instead of (10), the NIH estimation can also be recovered as a special case of (24). Indeed, by replacing eN with a zero field 0 and repeating the same steps to derive , the final result is the flux QNIH defined by

It is clear that, from (26), the effective conductivity is obtained in the same form as in the previous work [25].

Coupled method in special cases

The coupled algorithm is significantly accelerated if the shape functions I(ξ) or P(ξ) are determined from closed-form expressions, for example, in the case of ellipsoidal inclusions. Firstly, it is no longer necessary to compute numerically the Fourier transform of the characteristic function [28]. Secondly, the lattice sum can also be estimated by a closed-form expression.

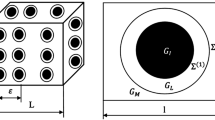

To illustrate these ideas, we consider the special cases where the spherical inclusions of radius R are located at the lattice points of cubic lattice systems (see Figure 1). The matrix and inclusions are assumed to be isotropic with conductivities k M and k I :

with I being the identity tensor. The Green tensor associated to the matrix admits a simple form:

By considering the symmetry with respect to ξ i = 0 planes and the permutation invariance, the lattice sum can be simplified into

Finally, the improved estimation is reduced to

The macroscopic flux from NIH approximation (26) has also a simple form:

where the term inside the parenthesis is the effective conductivity keff predicted by the approach. Since P(ξ) decays rapidly with |ξ|, the infinite sum can be estimated by keeping several initial terms and approximating the remainder with an improper integral:

The parameter ξ c defines the number of initial terms of the sum that we keep in the approximation formula. The final analytical expression is given in the following:

-

Simple cubic system

(33) -

with Si(η) being the sine integral

(34) -

Body-centered cubic system

(35) -

Face-centered cubic system

(36)

Results and discussion

In this section, we study the results coming from the implementation of the coupled method for the case of a simple cubic system. The representative cell is a cube with the spherical inclusion located at its center (the first figure from the left in Figure 1). The periodic problem with prescribed temperature gradient E is solved by three approaches: the NIH approximation (31), the conventional PIS, and the coupled method. The last two methods are based on the same iterative scheme, and in the coupled method, the reevaluation of the effective conductivity after each iteration is done using (30). All results are compared with the results coming from the conventional PIS method at convergence. The analytical expression of described in (33) is used to accelerate the computation and to improve the accuracy. Regarding the iterative scheme, the number of harmonic terms retained in the Fourier series is limited to 128*128*128, i.e., |n i | < 128, i = 1, 2, 3, and the precision of the computation ε = 0.001 is adopted. Different contrast ratios k I / k M ranging from 0.1 to 50 are considered in this work, and the results of the three approaches are discussed and compared.

From Figures 2, 3, 4, all curves, associated to the first case k I / k M = 10, are quite close at small volume fraction f but separate at high f. The significant improvement of the coupled method can be found at a small number of iterations, e.g., N = 5. In all cases under consideration, the coupling reduces significantly the difference between the conventional FFT method and the exact solution (see Figures 5, 6, 7). The coupled method results are also much more accurate than those issued from the pure NIH approximation which fails at high f.

Numerical examples at different contrast ra tios k I /k M also demonstrate a considerable improvement of the coupling in comparison with the basic FFT method. More particularly, for small k I /k M = 0.1, it generates a very good approximation of keff even at N = 1, 2, where the error of the FFT method is of order 20%. At high k I /k M = 50, the coupling performs less well but still reduces the relative error, the effect being important for lower number of iterations.

Conclusions

A coupled method is developed for computing the effective conductivity of periodic composites. The method uses a FFT iterative scheme to solve the localization problem and the NIH approximation to estimate analytically the remainder at any iteration N of the Neumann series. As a result, a new expression for the effective conductivity is derived on the basis of the current flux and temperature gradient field. Numerical tests on various cases have shown that the expression coming from the coupled method improves considerably the results issued from the uncoupled methods for small numbers of iterations. The contribution of the coupling improves the results at any contrast ratio and any volume fraction.

The application domain of the coupled method is large. Although the numerical examples given in this work concern the PIS scheme and spherical inclusions, the method can be applied to any existing FFT-based methods and arbitrary inclusion shapes to improve the accuracy of the predicted properties. The method can be extended to deal with other physical problems such as elasticity, piezoelectricity, etc.

References

Kellogg O: Foundations of potential theory. New York: Frederick Ungar; 1929.

Rayleigh L: On the influence of obstacles arranged in rectangular order upon the properties of a medium. Phil Mag 1892, 34: 481–502. 10.1080/14786449208620364

McPhedran RC, McKenzie DR: The conductivity of lattices of spheres. I. The simple cubic lattice. Proc R Soc Lond A 1978, 359: 45–63. 10.1098/rspa.1978.0031

McKenzie DR, McPhedran RC, Derrick G: The conductivity of lattices of spheres. II. The body centred and face centred cubic lattices. Proc R Soc Lond A 1978, 362: 211–232. 10.1098/rspa.1978.0129

Cheng H, Torquato S: Effective conductivity of periodic arrays of spheres with interfacial resistance. Proc R Soc Lond A 1997, 453: 145–161. 10.1098/rspa.1997.0009

Sangani AS, Acrivos A: The effective conductivity of a periodic array of spheres. Proc R Soc Lond A 1983, 386: 263–275. 10.1098/rspa.1983.0036

Eshelby JD: The determination of the elastic field of an ellipsoidal inclusion, and related problems. Proc R Soc Lond A 1957, 241: 376–396. 10.1098/rspa.1957.0133

McPhedran RC, Movchan AB: The Rayleigh multipole method for linear elasticity. J Mech Phys Solids 1994, 42: 711–727. 10.1016/0022-5096(94)90039-6

Helsing J: An integral equation method for elastostatics of periodic composites. J Mech Phys Solids 1995, 43: 815–828. 10.1016/0022-5096(95)00018-E

Eischen JW, Torquato S: Determining elastic behavior of composites by boundary element method. J Appl Phys 1993, 74: 159–170. 10.1063/1.354132

Kaminski M: Boundary element method homogenization of the periodic linear elastic fiber composites. Eng Anal Bound Elem 1999, 23: 815–823. 10.1016/S0955-7997(99)00029-6

Liu YJ, Nishimura N, Otani Y, Takahashi T, Chen XL, Munakata H: A fast boundary element method for the analysis of fiber-reinforced composites based on a rigid-inclusion model. J Appl Mech ASME 2005, 72: 115–128. 10.1115/1.1825436

Sheng P, Tao R: First-principles approach for effective elastic-moduli calculation: application to continuous fractal structure. Phys Rev B 1985, 31: 6131–6133. 10.1103/PhysRevB.31.6131

Tao R, Chen Z, Sheng P: First-principles Fourier approach for the calculation of the effective dielectric constant of periodic composites. Phys Rev B 1990, 41: 2417–2420. 10.1103/PhysRevB.41.2417

Michel JC, Moulinec H, Suquet P: Effective properties of composite materials with periodic microstructure: a computational approach. Comput Method Appl Mech 1999, 172: 109–143. 10.1016/S0045-7825(98)00227-8

Michel JC, Moulinec H, Suquet P: A computational method based on augmented Lagrangians and fast Fourier transforms for composites with high contrast. Comput Model Eng Sci 2000, 1: 79–88.

Michel JC, Moulinec H, Suquet P: A computational scheme for linear and non-linear composites with arbitrary phase contrast. Int J Numer Meth Engng 2001, 52: 139–160. 10.1002/nme.275

Eyre DJ, Milton GW: A fast numerical scheme for computing the response of composites using grid refinement. Eur Phys J Appl Phys 1999, 41–47.

Milton G: The theory of composites. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002.

Bhattacharya K, Suquet P: A model problem concerning recoverable strains of shape-memory polycrystals. Proc R Soc A 2005, 461: 2797–2816. 10.1098/rspa.2005.1493

Monchiet V, Bonnet G: A polarization-based fast numerical method for computing the effective conductivity of composites. Int J Numer Meth Heat Fluid Flow 2013,23(7):1256–1271. 10.1108/HFF-10-2011-0207

Monchiet V, Bonnet G: A polarization-based FFT iterative scheme for computing the effective properties of elastic composites with arbitrary contrast. Int J Numer Meth Eng 2012, 89: 1419–1436. 10.1002/nme.3295

Chen Y, Schuh CA: Analytical homogenization method for periodic composite materials. Phys Rev B 2009, 79: 094104–094114.

Nemat-Nasser S, Iwakuma T, Hejazi M: On composites with periodic structure. Mech Mater 1982, 1: 239–267. 10.1016/0167-6636(82)90017-5

To QD, Bonnet G, To VT: Closed-form solutions for the effective conductivity of two-phase periodic composites with spherical inclusions. Proc R Soc A 2013, 469: 1471–2946.

Strelniker YM, Bergman DJ: Theory of magnetotransport in a composite medium with periodic microstructure for arbitrary magnetic fields. Phys Rev B 1994, 50: 14001–14015. 10.1103/PhysRevB.50.14001

Bergman DJ, Strelniker YM: Calculation of strong-field magnetoresistance in some periodic composites. Phys Rev B 1994, 49: 16256–16268. 10.1103/PhysRevB.49.16256

Bonnet G: Effective properties of elastic periodic composite media with fibers. J Mech Phys Solids 2007, 55: 881–899. 10.1016/j.jmps.2006.11.007

Hoang DH: Contribution à l’homogénéisation de matériaux hétérogènes viscoélastiques. Milieux aléatoires et périodiques et prise en compte des interfaces. Université Paris Est Marne la Vallée: PhD thesis; 2011.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

To Q.D. carried out the numerical and analytical computation. Bonnet G. provided his original numerical FFT code and proposed the present estimation scheme.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

To, Q.D., Bonnet, G. A numerical-analytical coupling computational method for homogenization of effective thermal conductivity of periodic composites. Asia Pac. J. Comput. Engin. 1, 5 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/2196-1166-1-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2196-1166-1-5