Abstract

The Chinese have always been identified as gamblers, and they accept this. However, apart from state lotteries, the people of China have not been exposed to a situation where games have been legitimized and made generally available. According to recent literature, there are significant problems related to gambling in many jurisdictions around the world where a critical mass of people of Chinese origin have access to state gambling. Overseas Chinese are table game enthusiasts and are also turning to electronic gambling machines (EGMs), which are recognized as the games most likely to be associated with harmful gambling and pathological gambling. In Mainland China, EGM are now being widely introduced. This discussion paper is built on a synthesis of anthropological knowledge about Chinese culture and a non systematic review of current literature about Chinese culture and gambling. We have tried to answer the following question: if such machines are now introduced in large numbers in China, what are the implications for public health if the games are as popular as projections would have them? Given our knowledge of the correlation between Chinese culture and games of chance and money – and in light of the sensational popularity of casinos in Macao – the introduction of electronic gambling machines in China should become popular and could have important consequences on the population’s health. When the negative effects are felt, the Chinese regime may be unlikely to listen to civil society which, as in other jurisdictions where EGMs are operated, will try too late and within the limits of the freedom granted in China, to mitigate the impacts of those games.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The meaning of games of chance and money

Gambling involves games in which money, or any other object or action that has value, is bet on the result. From the point of view of at least one of the participants, this result is based in whole or in part on chance. Why gamble? Among a wide variety of the material and symbolic functions of gambling are the desires for relaxation, excitement, socialization, challenge, and an esthetic quest. Gambling can also be an escape from difficult situations. But generally, the hope for significant gains and improving one’s economic situation constitutes the leading motivation. The reasons for gambling can also be linked with cultural traits: in the Chinese community, apart from the desire for prosperity, gambling has oracular, numerological, and predictive functions (Papineau,2000); among the Vietnamese, gambling is part of the Buddhist concept of qubao (retribution) and the yin-yang cycle of gains and losses (Ohtsuka and Ohtsuka,2010). The practice of the Chinese-Malaysians was to ask the winning numbers of the gods through a medium, while the richest among them did not consider gambling losses as losses at all, rather as the equivalent to offerings to Buddha and therefore investments in the future prosperity of the clan and one’s descendants (Nonini,1979).

The Chinese context

In ancient China, gambling was popular although stigmatized, and decrees prohibiting such and such game followed one another relentlessly (Yang,1990). Under the Qings, the makers of gambling accessories and citizens who accepted them as gifts were liable to expulsion or to 100 blows with a stick (Xu & Luo,1994). In Maoist China, gambling became synonymous with capitalist evil and speculation, contrary to the ethic of labour and selflessness as prescribed by chikuzaiqian, xianglezaihou ( – “Work first, then pleasure”)a.

– “Work first, then pleasure”)a.

After the hard-line communist era and during the so-called open and reform period of the 1980s ( ), notions of leisure and pleasure became increasingly legitimate and even commonplace. In the past 30 years in China, as elsewhere in the world, gambling and the “culture of chance” have mushroomed: “Today, everything must be exciting. All types of contests, sports competitions, literary awards offer monetary or material prizes. For management performance review there is the perfect mark; each store organizes its commercial awards; companies organize monthly contests, their prizes rewarding a sense of economy or innovation; all the way to the government, which gathers donations or offers savings plans accompanied by prizes. In society today, there’s no end to the contests; the prizes and awards rain down on us…” (Ding,1991– in translation).

), notions of leisure and pleasure became increasingly legitimate and even commonplace. In the past 30 years in China, as elsewhere in the world, gambling and the “culture of chance” have mushroomed: “Today, everything must be exciting. All types of contests, sports competitions, literary awards offer monetary or material prizes. For management performance review there is the perfect mark; each store organizes its commercial awards; companies organize monthly contests, their prizes rewarding a sense of economy or innovation; all the way to the government, which gathers donations or offers savings plans accompanied by prizes. In society today, there’s no end to the contests; the prizes and awards rain down on us…” (Ding,1991– in translation).

This slide toward a culture of chance is accompanied by more leisure and the legitimization of pleasure. The transition from a six-day work week to five in 1994 and 1995 brought more free time, associated with a higher standard of living for part of the Chinese population, as illustrated by its lifestyle revolution. The diversification, Westernization, and computerization of leisure activities offered to the Chinese since the 1980s has created no less than a “leisure market,” enabling individuals to relax in a multitude of ways but also to make their leisure activity a symbol of their success and status (Sue,1991).

In 1987, following increased pressure to liberalize the sector, the Ministry of Civil Affairs created the Lottery for Social Well-Being ( ), which in 1995 was followed by the Sports Lottery (

), which in 1995 was followed by the Sports Lottery ( ). The lotteries have broken record after record since their creation. Since 2007, annual lottery sales exceed $100 billion yuans, with an annual increase of 25% (AGTech Holding Limited,2011).

). The lotteries have broken record after record since their creation. Since 2007, annual lottery sales exceed $100 billion yuans, with an annual increase of 25% (AGTech Holding Limited,2011).

In fact, the Chinese government understood its people’s attraction to lotteries so well that in 1998, to eradicate tax evasion, it created lottery-receipts – an official sales receipt that incorporates a lottery ticket to encourage consumers to ask for state receipts in goods and services businesses. Since consumers did not want to miss an opportunity to gamble, “The lottery receipt experiment has significantly raised the business tax, the growths of business tax and total tax revenues” (Wan,2006).

Problematic

The expansion of gambling

From the year 2000 on, ideological underpinnings have melted like snow in the spring sun, and several indices revealed that the central government was laying the groundwork for an unprecedented expansion of games of chance and money. First, in 2002, encouraged by the Ministry of Finance, Peking University established the China Center for Lottery Studies, whose mission is to facilitate “a healthy development of the Chinese lottery and gaming industry” (China Center for Lottery Studies,2009). In addition, the business lobby very freely expressed its views on the benefits of the gambling market: “an important role in improving China’s fiscal and tax revenue, providing employment chances, stimulating consumption demand, speeding up the economic growth and advancing the development of sports and welfare undertakings” (Wu & Gan,2003). Finally, as elsewhere in the world when gambling is undergoing a period of expansion, the main argument used to justify the growth, other than the notion of contribution to “social well-being,” was the idea that it would eradicate illegal gambling. Various sources, such as the CCLS, suggested that the sums diverted from the Chinese economy to illegal gambling and overseas games via the Internet were nine to ten times those spent on state games. Repatriation of those fiscal losses therefore constituted the key to legitimizing gambling in China in recent years, more recently stimulated by the economic benefits generated by Macau (Bourrier,2007), which held out the possibility of a gold mine in the expansion of some games of chance and money in the People’s Republic. In 2005, to stake out its territory and eliminate competition, the government clarified article 303 of the criminal act on the offence of illegal gambling (particularly Internet gambling) (Xinhua News,2005). In the aftermath, the government proceeded with severe and largely publicized repression campaigns: 700 000 people detained for the offence of illegal gambling in the first half of 2005 alone (Coleman,2005). In 2008, Public Security uncovered 361 000 gambling enterprises, made 1.13 million arrests, dismantled 20 000 gambling networks, and confiscated 2.07 million yuans (People’s Daily online,2008).

The Chinese government thus followed the world trend to make gambling and particularly electronic gambling machines, whose returns are phenomenal, a strategy for contributing to if not rebuilding public finances. Electronic gambling machines (EGMs)– marketed in the high-frequency lottery category and called online lottery terminals ( ) – are part of the Chinese landscape where they are more numerous than at Macau: 14 000 machines were distributed to 530 gaming halls in 2005 (Coleman & Mure,2007), while the Deutsche Bank predicted that the number could rapidly increase to 150 000 machines in 5000 halls (Coleman, op.cit.). In addition to those gambling outlets, the government announced 10 000 Keno gambling terminals, which offer a draw every five minutes. However, in 2008 “social incidents” led the government to temporarily halt the expansion of electronic gambling machines in China, as “some people were losing more money than they could afford” (ASGAM,2008). The campaign restarted after several measures were implemented: “Because of the addictive nature of this game, many players actually chased losses in hoping that they would win back money, some selling their housing for more money to buy lottery and some even committing suicide. Some significant adjustments were made in China since 2008, including but are not limited to the following: (a) some strong addictive and habit forming games had been terminated; (b) lottery spending had been limited to ¥200 per person per day; (c) payouts for all gambling types were increased from 50 to 65%b; (d) business hours were adjusted from 10:00 a.m. to 22:00 p.m. every day; (e) VIP room was cancelled, shelters discarded, and monitoring video camera installed; and (f) some misleading promotions, such as posters, about winning the game were prohibited” (Li, Zhang, & Mao,2011).

) – are part of the Chinese landscape where they are more numerous than at Macau: 14 000 machines were distributed to 530 gaming halls in 2005 (Coleman & Mure,2007), while the Deutsche Bank predicted that the number could rapidly increase to 150 000 machines in 5000 halls (Coleman, op.cit.). In addition to those gambling outlets, the government announced 10 000 Keno gambling terminals, which offer a draw every five minutes. However, in 2008 “social incidents” led the government to temporarily halt the expansion of electronic gambling machines in China, as “some people were losing more money than they could afford” (ASGAM,2008). The campaign restarted after several measures were implemented: “Because of the addictive nature of this game, many players actually chased losses in hoping that they would win back money, some selling their housing for more money to buy lottery and some even committing suicide. Some significant adjustments were made in China since 2008, including but are not limited to the following: (a) some strong addictive and habit forming games had been terminated; (b) lottery spending had been limited to ¥200 per person per day; (c) payouts for all gambling types were increased from 50 to 65%b; (d) business hours were adjusted from 10:00 a.m. to 22:00 p.m. every day; (e) VIP room was cancelled, shelters discarded, and monitoring video camera installed; and (f) some misleading promotions, such as posters, about winning the game were prohibited” (Li, Zhang, & Mao,2011).

This government intervention, which was minimally documented, had all the appearances of a new awareness of the dangers intrinsic to electronic gambling machines and a will to govern with precaution. But gambling development since 2010 proves this interpretation wrong. According to Mr. Liao of the China Lotsynergy, the electronic gambling machine market has renewed its energy, and access to other forms of gambling is expected to increase. “The lottery in China is regarded as a means for the government to raise revenue to help the poor and needy, but the Ministry of Finance realised that the majority of participants in China’s lottery were poor, so effectively, the government was collecting from the poor to help the poor. In order to increase the proportion of more rich people participating in the China lottery, the government decided to approve more ‘aggressive’ lottery products including sports betting (…) There were two policies issued by the Ministry of Finance in October last year, allowing lottery products in China to be sold on the Internet and mobile phones” (ASGAM, op.cit.). What are the potential implications of this new “aggressive” marketing of games in China, particularly the marketing of electronic gambling machines?

It has been observed that everywhere EGMs are operated they generate significant gambling problems, putting the state in an ambiguous position of promoting games that make an increasing proportion of gamblers ill. From a public health perspective, gambling problems, which are clearly more remarkable among online and electronic gamblers, are determined by a complex interaction of structural characteristics specific to gambling (danger of gambling in itself), individual aspects specific to gamblers, and environmental aspects such as access to games, ease of payment, and the opportunity for drinking alcohol while gambling (Korn et al.,2003; Papineau,2009). This framework has numerous implications for prevention: knowing that the most dangerous games will exacerbate gambling problems (ex.: video lottery terminals vs. Bingo), prevention must aim to reduce danger or increase the harmlessness of the games being offered (Chevalier & Papineau,2007). It must also seek to reduce access to and the marketing of the most dangerous games because it has been clearly demonstrated that the easier it is to access games of chance and money, the more people there will be with problems (Australian Productivity Commission,1999; Abbott & Volberg,1994; Ladouceur,1996; Welte et al.,2004; Harrison Health Research,2006). Before testing this public health perspective on the Chinese context, it is important to understand specifically the elements related to the product, the individual, and the environment inherent in Chinese gambling.

The intrinsic danger of electronic gambling machines

Griffith and Wood (1999) conclude that among all forms of gambling electronic gambling machines are the most likely to be linked with gambling problems. The speed that problems develop with EGMs is greater than for other games (1.08 years vs. 3.58 years) (Breen & Zimmerman,2002). The data show that 68.5% of annual spending by Quebecers on video lottery terminals is made by 14% of those people who have a gambling problem with VLTs (Chevalier et al.,2004). Several studies confirm this state of affairs and report that pathological gamblers contribute on average 46% of video lottery terminal income – the proportions varying between 27% and 67% (Australian Productivity Commission1999); Azmier & Smith,1998; Nova Scotia Department of Health,1998; Volberg, Gerstein, Christiansen, & Baldridge,2001; Doiron, Rowling,1999; Smith, & Wynne,2002).

The literature attributes this situation to two main factors: the technical characteristics intrinsic to the machines and their temporal, geographic, symbolic, economic, and legal accessibility (Leblond,2004; Dowling, Smith & Thomas,2005; Wood et al.,2004; Griffiths,1993; Chevalier & Papineau,2004; Abbott,2006). One of the main characteristics of electronic gambling machines is to make players believe they are about to win or that their chances of winning are greater than in reality. To do this, the symbols’ probability of occurrence are not respected but rather weighted by the manufacturer in such a way as to generate “near misses” or numerous small gains that keep the gambler tied to the game (Falkner & Horbay,2006, Dixon et al.,2010;2011). According to Skinner’s (1953) principle of intermittent positive reinforcement, the addition of a stimulus as the consequence of an action will increase the probability of the action being repeated. The chance to play continuously and repetitively and the intermittent reinforcements from small gains stimulate dopamine and noradrenalin, two known anti-depressants. Gamblers may develop an addiction to these neurophysiologic states (Sader,2005; Anderson & Brown,1984; Dixon et al.,2011).

Other EGM pathogenic elements are identified (Griffiths,1993; Wood et al.,2004; Harrigan,2007; Harrigan & Dixon,2009, Dow-Schull,2012): They have short reward intervals of only a few seconds (in other words accelerated frequency of events), allowing neither reflection nor a return to reality. Each game is not costly in a deceiving way: they cost a few cents but each game lasts a few seconds only: since machines accept bills instead of change, the costs add up quickly. Machines that work with magnetic cards create a desensitization effect to money on the user. On another hand, those machines require no skill: some characteristics such as the possibility of manually stopping the game and the fact that card games (theoretically strategic games) are coupled with games of pure chance induce gamblers into thinking that they have control over the results and that the more they play the more they can increase their performance.

Elements of individual and cultural vulnerability

The Chinese are now exposed to these games, strategically adapted to their tastes and culture (ASGAM,2008). In the environment of the Macau casinos, the Chinese seem more inclined to play table games rather than electronic machines (Liu & Wan,2011). However, no academic research has yet evaluated the situation in the gambling halls of the People’s Republic. But various factors highlighted by the research suggest that the inner characteristics and the high level of accessibility of electronic gambling machines in China may lead to a rise of psychosocial problems.

According to several studies, the Chinese have certain individual and cultural determinants that could influence the trajectory of gambling problems, particularly in terms of beliefs (Ladouceur & Walker,1996; Hong & Chiu,1988; Zeng,2006; Ariyabuddhiphongs & Phengphol,2008):

-

For the Chinese population, the ban on gambling prior to the period of reform and openness reinforced misconceptions about the chances of winning and the general functioning of state lotteries (Ozorio & Ka-Chio Fong,2004). For example, video lottery terminals lead to negative gain over the long term because the advantage is necessarily for the “house” (the operator). The experience of majiang or poker played as a family – during which all monies gambled are redistributed among the players – did not prepare gamblers for the notion of long-term losses that are ensured by state-owned video lottery terminals.

-

Traditionally, the Chinese have not perceived lotteries as a hard form of betting (

) (Sin,1997). Meanwhile, electronic gambling machines are marketed in China as “online lotteries” (

) (Sin,1997). Meanwhile, electronic gambling machines are marketed in China as “online lotteries” ( ) – a marketing bias likely to minimize the dangers of addiction to these games.

) – a marketing bias likely to minimize the dangers of addiction to these games. -

From the start, the Chinese have a tendency to prefer games based on numbers or cards (roulette, black jack, poker): they attribute a divine power to numbers drawn randomly or attribute an influence to themselves on game results when they choose the numbers, which constitutes a hook factor for the game (Papineau,2005; Ohtsuka & Chan,2010).

-

The propensity of Chinese gamblers to develop strategies and assume regularity in games of pure chance has been demonstrated with the fantan, a popular game in the south of China, particularly during the Republic: “In particular, it was observed that gamblers “narratize” the game by considering successive draws not as independent, as mathematical laws of probability show, but rather as a sequence in which the combinations make sense. For this reason, the house of fantan provides for clients upon their arrival a history of the draws that took place in the preceding hours. There is indeed a whole group of strategies (tanlu

) associated with very precise terminology on how to choose the entries for betting in several consecutive games” Paules,2007, – in translation. See alsoPaules 2010). This type of erroneous belief regarding the expectation of winning, the illusion of control, and the principle of independence among events is common among VLT gamblers (Gaboury & Ladouceur,1989). If the results of electronic gambling machines are based entirely on chance, they are designed and programmed on the one hand to give the impression of skill and on the other to generate these erroneous beliefs.

) associated with very precise terminology on how to choose the entries for betting in several consecutive games” Paules,2007, – in translation. See alsoPaules 2010). This type of erroneous belief regarding the expectation of winning, the illusion of control, and the principle of independence among events is common among VLT gamblers (Gaboury & Ladouceur,1989). If the results of electronic gambling machines are based entirely on chance, they are designed and programmed on the one hand to give the impression of skill and on the other to generate these erroneous beliefs.Studies focusing on the psychological aspects of making decisions in China demonstrate characteristics that could contribute to an explanation for the propensity for gambling and the greater prevalence of problem gamblers among Asian people. Three studies, in particular, demonstrate that in situations of investment and games the Chinese take more risks and show less probabilistic thinking, in an effort to reach material comfort more quickly (Vong,2007; Lau & Ranyard,2005). They also show an external locus of control – a tendency to attribute important life events to external causes: “The feeling that major reward allocation decisions are left in the hands of other powerful persons is frustrating and more likely to trigger the motivation to regain illusory control experienced in gambling” (Hong & Chiu,1988)c. Therefore, through this interpretation, gambling enables a sense of liberating interaction, if not influence, regarding events and destiny. This propensity is perhaps linked to some degree to the traditional Chinese “fatalistic” thinking (Papineau,2005), but could have a significant influence to the Chinese players’ relation with the EGM.

Discussion

Elements of socio-environmental vulnerability

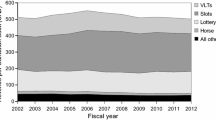

For all the above reasons and due to increased access to electronic games in China, it can be expected that the Chinese will largely adopt the games. As with the Fantan (Paules, op.cit.), they are simple, accessible games with very minimal basic cost of bets. Indeed, the rate of VLT adoption is increasing rapidly, as confirmed by China Lotsynergy, the supplier of VLT operating systems for the China Welfare Lottery (CLO): “Although revenue from video lottery terminals (VLTs) run by the CWLC accounted for only 8.0% of China’s total lottery sales in Q1 2011, they had grown 159% year on year in the quarter, and look set to be one of the fastest growing components of the market” (ASGAM,2011).

In various jurisdictions where the problem has been studied, Chinese communities showed more gambling problems than the general population (Blaszczynski, Huynh, Dumlao & Farrell,1998; Chen et al.1993; Yeh, Hwe, & Lin,1995; Sin,1997). Several Western studies associate the availability of electronic gambling machines with an increase in the prevalence of gambling problems, which suggests that Chinese society will not be spared (National Research Council,1999). The problems expected with the introduction of EGMs may be exacerbated by the common acceptance of gambling in general, by the lack of knowledge of pathological gambling as a psychosocial and public health problem, and finally by the concern for saving face. Although a growing amount of scientific research has been done recently in Hong-Kong and Taïwan about gambling (Loo, Raylu & Oei,2008), mainland China does not readily recognize excessive gambling as a psychosocial or mental health problem: “The negative perception toward pathological gambling is further reinforced by the reluctance of the psychiatric profession to recognise the behaviour as a mental health problem as evidenced by its decision to exclude pathological gambling from the China Classification of Mental Disorders (CCMD-2-R, 1995)” (Blaszczcynski et al.,1998).

Excessive gambling has traditionally been associated in Chinese propaganda campaigns with the “scourges” of prostitution, drugs, and criminality. Attenuating circumstances such as mental illness are not recognized in explanations of the marginal behaviour in individuals; only poor social influences are considered as the source of the deviance and with that comes condemnation and punishment, sometimes re-education, constituting the main means of intervention. As Sing Lee says, in Chinese society, “people who gamble immoderately and ruin their life are considered bad rather than mad” (Lee,1996). Gambling as a form of betting (with more or less significant wagers required) is so widespread that “only very extreme addicts are identified.” According to Wei Shujie (2000), a Shanghai psychologist who specializes in the trans-cultural study of mental illness, considering Western criteria, a large part of the population is at high risk, if not excessive gamblers, without knowing it.

A gambler’s non-recognition or under-evaluation of the problem to “save face” is another important factor that risks compromising detection, prevention, and recourse to professional assistance (Loo, Raylu & Oei,2008) for problems likely to stem from the marketing of electronic gambling machines. Finally, a tradition of lending among loved ones and informal credit in China may enable a gambler to continue at a loss for a long time without his or her loved ones detecting the gambling problem.

In Western countries that have seen a growth in games of chance and money in the past 20 years, a scientific field related to gambling has emerged, the most prevalent paradigms of gambling being the market (Cosgrave,2006) and the medical views (Castelanni,2000). Multinational gambling companies and state suppliers have adopted the convenient concept of “responsible gambling” (Blaszczynski et al.,2004;2011), which enables them to claim a certain corporate social responsibility. This concept mainly puts the burden of “control” on the gambler, largely exonerating the game supplier from its own control over games dangerousness and accessibility and strangely ignoring the question of the wide promotion of gambling on “informed consumer choice” (Reith,2008; Cosgrave,2010). It seems that the Chinese have already partially adopted this discourse: the main supplier of electronic gambling machines argues that “in view of the distinctive features of the gaming industry, China LotsSynergy earnestly avoids the negative influences of lottery over the society through the promotion of positive values of community caring and social entertainment. CLS is dedicated to the development of ‘responsible gaming.’ It offers its customers a user-friendly and responsible gaming platform with its professional knowledge and advanced technology” (ChinaLotsynergy 2010).

However, in the West, in reaction to the unilateral discourse of individual responsibility by the problem gambler, the media, civil society, pressure groups, independent researchers, psychosocial workers, and public health leaders have taken action in the public domain to limit the impact of games of chance and money (Hing,2011). The actual debate in Australia concerning pre-commitment on EGM is showing too well how fierce a debate can become, how strong are lobbys, but how necessary are civil society and free researchers voices. These various groups oppose the logic of the free market and the concept of the consumer sovereignty, which are defended by the industry and game suppliers, with arguments regarding health and equity, favouring a sense of judgment and caution in the provision of gambling.

Is this counterweight possible in China – for civil society, the community of researchers, and the fourth estate to oppose the increasing commercialization of electronic gambling machines? When the negative effects are felt, the Chinese regime may be unlikely to listen to civil society which, as in other jurisdictions where EGMs are operated, will try too late to mitigate the impacts of those games. The Chinese regime in fact leaves little room for expression by civil society or for demands by citizen groups harmed by development. “During the first two decades of the reform era, several vectors of change suggested the emergence of a civil society through the development of NGOs in particular. But since the mid-2000s, the Chinese communist party tightened the vice on voices deemed dissident while welcoming into its fold those who accept to play the role of advisor to the prince without challenging the establishment (…)” (Dulery,2011– in translation).

Conclusion

Games have a social function: in Chinese history, the traditional game weiqi (game of Go) was synonymous with beauty, dignity, intelligence, harmony, serenity. Its practice offered a counterweight to the agitation of the world and in slow games measured people seeking wisdom and nobility (Papineau,2000). In today’s society, in which the ultimate brand of success is to display material prosperity (Meyer,2002), electronic gambling machines could appear as a new miraculous activity offering the possibility of righting an unsatisfactory economic condition as well as dreams of changing one’s social status. In the context of extreme professional competitiveness in the quest for economic or symbolic capital, which would bring social and family influence, electronic gambling machines may also appear as a gentle drug that lets one “disconnect,” escape, dream. However, due to many historical and cultural reasons and due to the addictive potential of the machines, without recourse to caution in this unopposed commercialization, the problems observed in the West may well emerge in China before long, in relative terms.

Endnotes

a Or: “Be in the front in bearing suffering, and be in the rear in enjoying the pleasure of life.” Liu Shaoqi, in “How to be a good Communist” (1939).),

b This is not a protection measure. See Leblond (2007). Dangerosité des appareils électroniques de jeu et mesures de protection. Analysis document submitted to the Capitale-Nationale (Quebec City) director of public health as part of writing work for the “Avis de santé publique sur l’implantation des salons de jeux au Québec” (public health opinion on establishing gambling halls in Quebec). Quebec City, QC.

c The locus of control is a personality variable that describes to what extent individuals believe in their own control over their experiences. Those with an external locus of control tend to attribute such experiences to destiny, chance, other people, and not to their own influence, efforts, or behaviour.

References

Abbott M: Do EGMs and problem gambling go together like a horse and carriage? Gambling Research 2006, 18: 7–38.

Abbott R, Volberg M: Gambling and Pathological Gambling: Growth Industry and Growth Pathology of the 1990’s. Community Mental Health in New Zealand 1994,9(2):22–31.

AGTech Holdings Limited: An overview of China lottery industry. Retrieved November 2011. 2011. http://www.agtech.com/html/industry_lottery_overview_char.php

Anderson G, Brown RIF: Real and laboratory gambling, sensation seeking and arousal: Toward a Pavlovian component in general theories of gambling and gambling addictions. British Journal of Psychology 1984, 75: 401–411. 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1984.tb01910.x

Ariyabuddhiphongs V, Phengphol V: Nearmiss, gambler’s fallacy and entrapment: Their influence on lottery gamblers in Thailand. Journal of Gambling Studies 2008, 24: 295–305. 10.1007/s10899-008-9098-4

ASGAM: The Right Slot: Asians love gaming machines—as long as the content is right. Inside Asian Gaming Magazine 2008, 8: 19–08. Retrieved November 2011http://www.asgam.com/article.php?id_article=1713 Retrieved November 2011

ASGAM: Bigger Draw. China Lotsynergy Executive Vice President and CFO Daniel Liao explains the background to the Chinese central government’s decision to expand the distribution channels for the country’s lottery products. 2011. http://www.asgam.com/cover-stories/item/1242-bigger-draw.html

Australian Productivity Commission: Australia’s Gambling Industries, Report no. 10. Canberra, Australia: Ausinfo; 1999. Retrieved December 2011.http://www.pc.gov.au/projects/inquiry/gambling/docs/finalreport Retrieved December 2011.

Azmier J, Smith G: The state of gambling in Canada: an interprovincial roadmap of gambling and its impact. Calgary, AB: Canada west foundation; 1998. Retrieved December 2011http://cwf.ca/CustomContentRetrieve.aspx?ID=1482259 Retrieved December 2011

Blaszczynski A, Huynh S, Dumlao VJ, Farrell E: Problem gambling within a Chinese speaking community. Journal of Gambling Studies 1998,14(4):359–380. 10.1023/A:1023073026236

Blaszczynski A, Ladouceur R, Shaffer HJ: A science-based framework for responsible gambling: the Reno model. Journal of Gambling Studies 2004, 20: 301–317.

Blaszczynski AP, Collins P, Fong D, Ladouceur R, Nower L, Shaffer HJ: Responsible gambling: General principles and minimal requirements. Journal of Gambling Studies 2011, 27: 565–573. 10.1007/s10899-010-9214-0

Bourrier A: Des casinos extravagants sous tutelle chinoise. Macao entre jeux et insoumission. Le Monde Diplomatique 2007, 12. http://www.monde-diplomatique.fr/2007/09/BOURRIER/15066

Breen RB, Zimmerman M: Rapid onset of pathological gambling in machine gamblers. Journal of Gambling Studies 2002, 18: 31–44. 10.1023/A:1014580112648

Castellani B: Pathological gambling: The making of a medical problem. Albany: State University of New York Press; 2000.

Chen CN, Wong J, Lee N, Chan-Ho MW, Lau JT-F, Fung M: The Shatin Community Mental Health Survey in Hong Kong: II Major Findings. Archives of General Psychiatry 1993, 50: 125–133. 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820140051005

Chevalier S, Papineau E: Public policy in gambling: scientific knowledge and other contingencies –the Quebec case. Halifax, Nova Scotia: Paper presented at "Myths, Reality and Ethical Public Policy", International Problem Gambling Conference; 2004.

Chevalier S, Papineau É: Analyse des effets sur la santé des populations des projets d’implantation de salons de jeux et d’hippodromes au Québec. Rapport déposé aux directeurs régionaux de santé publique, Direction de santé publique de Montréal- INSP; 2007. http://www.jeu-compulsif.info/documents/Rapport_scientifique_salons_de%20jeux_FINAL.pdf

Chevalier S, Hamel D, Ladouceur R, Jacques C, Allard D, Sévigny S: Comportements de jeu et jeu pathologique selon le type de jeu au Québec en 2002. QC: Institut national de santé publique du Québec et Université Laval, Montréal et Québec; 2004.

China Center for Lottery Studies: China Center for Lottery Studies (n.d.). 2009.

China Lotsynergy: About China LotSynergy - Social Responsibility. 2010. http://www.chinalotsynergy.com/en/Social.html

Coleman Z: A sure bet. The Standard, 29 October 2005. 2005.

Coleman Z, Mure D: High stakes in a lottery frenzy. Financial Times, 8 May 2007. 2007. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/5e2d3c0a-fd7b-11db-8d62–000b5df10621.html

Cosgrave J: Introduction: Gambling, risk and late capitalism. In The sociology of risk and gambling reader. Edited by: Cosgrave J. New York: Routledge; 2006:1–24.

Cosgrave J: Embedded addictions: The social production of gambling knowledge and the development of gambling markets. The Canadian Journal of Sociology 2010, 35: 113–133.

Ding H: Nongcun majiang feng tanmi (Investigation on majiang fever in rural areas). Shehui (Society) 1991, 12: 9–21.

Dixon MJ, Harrigan KA, Sandhu R, Collins K, Fugelsang JA: Losses disguised as wins in modern multi-line video slot machines. Addiction 2010, 105: 1819–1824. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03050.x

Dixon MJ, Harrigan KA, Jarick M, MacLaren V, Fugelsang JA, Sheepy E: Psychophysiological arousal signatures of near-misses in slot machine play. International Gambling Studies 2011, 11: 393–407. 10.1080/14459795.2011.603134

Doiron J, Nicki R: The prevalence of problem gambling in Prince Edward Island. Charlottetown, IPE: Prince Edward Island Department of Health and Social Services; 1999. http://www.gov.pe.ca/photos/original/gambling.pdf

Dowling N, Smith D, Thomas T: Electronic gaming machines: Are they the crack cocaine of gambling? Addiction 2005, 100: 33–45. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.00962.x

Dow-Schüll N: Addiction by design by Design -Machine Gambling in Las Vegas. Princeton University Press; 2012.

Dulery F: Aujourd'hui la Chine. Montpellier (FRA); Chasseneuil du CRDP; CNDP, Coll. Questions Ouvertes. 2011, 12. ISBN 978–2-86626–429–1 ISBN 978-2-86626-429-1

Falkner T, Horbay R: Unbalanced reel gaming machines. 2006. http://www.gameplanit.com/UnbalancedReels.pdf

Gaboury A, Ladouceur R: Erroneous perceptions and gambling. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality 1989, 4: 411–420.

Griffiths MD: Fruit machine gambling: The importance of structural characteristics. Journal of Gambling Studies 1993, 9: 101–120. 10.1007/BF01014863

Griffiths MD, Wood R: Le jeu de loterie et la dépendance en Europe. Panorama no.1. 1999. http://www.academia.edu/857240/Griffiths_M.D._and_Wood_R.T.A._1999_._European_lottery_gambling_and_addiction._Panorama_European_State_Lotteries_and_Toto_Association_1_12–16

Harrigan KA: Slot machine structural characteristics: Creating near misses using high symbol award ratios. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 2007, 6: 353–368.

Harrigan KA, Dixon M: PAR Sheets, probabilities, and slot machine play: Implications for problem and non-problem gambling. Journal of Gambling Issues 2009, 23: 81–110.

Harrison Health Research: Evaluation of 2004 Legislative Amendments to Reduce EGMs Research report. South Australia: Independent Gambling Authority; 2006.

Hing N: The evolution of responsible gambling policy and practice: Insights for Asia from Australia. Asian Journal of Gambling Issues and Public Health 2011, 1: 19–33.

Hong Y, Chiu C: Sex, locus of control, and illusion of control in Hong Kong as correlates of gambling involvement. The Journal of Social Psychology 1988, 128: 667–674. 10.1080/00224545.1988.9922920

Korn D, Gibbons R, Azmier J: Framing public policy towards a public health paradigm for gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies 2003, 19: 235–256. 10.1023/A:1023685416816

Ladouceur R: The prevalence of pathological gambling in Canada. Journal of Gambling Studies 1996, 12: 129–142. 10.1007/BF01539170

Ladouceur R, Walker M: A cognitive perspective on gambling. In Trends in cognitive and behavioral therapies. Edited by: Salkoskvis PM. New York: Wiley; 1996:89–120.

Lau LY, Ranyard R: Chinese and English probabilistic thinking and risk taking in gambling. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 2005, 36: 621–627. 10.1177/0022022105278545

Leblond J: Évaluation de la dangerosité des ALV. 2004. http://www.jeu-compulsif.info/rapport-leblond-recours_collectif/cahier-1-comp.pdf

Leblond J: Dangerosité des appareils électroniques de jeu et mesures de protection. Research report submitted to the Capitale-Nationale Director of Public Health. QC: Quebec City; 2007. http://www.dspq.qc.ca/publications/Leblond_Jean_2007–02–20_Dangerosite_des_App-elec_mesures-protection.pdf

Lee S: Cultures in psychiatric nosology: The CCMD-2-R and international classification of mental disorders. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 1996, 20: 421–472. 10.1007/BF00117087

Li H, Zhang JJ, Mao LL: Assessing corporate social responsibility in China’s Sports Lottery Administration and its influence on consumption behavior. Journal of Gambling Studies 2011. Published online: 17 September 2011 Published online: 17 September 2011

Liu XR, Wan YKP: An examination of factors that discourage slot play in Macau casinos. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2011, 30: 167–177. 10.1016/j.ijhm.2010.06.003

Loo JMY, Raylu N, Oei TPS: Gambling among the Chinese: A comprehensive review. Clinical Psychology Review 2008, 28: 1152–1166. 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.04.001

Meyer E: Sois riche et tais-toi. Portrait de la Chine d’aujourd’hui. Paris, Éditions Robert Laffont; 2002.

National Research Council (NRC): Pathological Gambling: A Critical Review. National Academy Press, Washington, DC; 1999.

Nonini D: The mysteries of capital accumulation, honouring the gods and gambling among Chinese in a Malaysian market town (Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Asian Studies, Volume 3). Southeast Asia: Hong Kong Asian Research Service; 1979.

Nova Scotia Department of Health: 1997/98 Nova Scotia video lottery players’ survey. In Edited by: Halifax NS. 1998.http://www.gov.ns.ca/hpp/publications/VL_players_survey_9798.pdf

Ohtsuka K, Chan CC: Donning red underwear to play mahjong: Superstitious beliefs and problem gambling among Chinese mahjong players in Macau. Gambling Research 2010, 22: 18–33.

Ohtsuka K, Ohtsuka T: Vietnamese Australian gamblers’ views on luck and winning: Universal versus culture-specific schemas. Asian Journal of Gambling Issues and Public Health 2010, 1: 34–46.

Ozorio B, Fong DK: Chinese casino gambling behaviors: Risk taking in casinos vs. investments. UNLV Gaming Research & Review Journal 2004, 8: 27–38.

Papineau É: Le jeu dans la Chine contemporaine: Mah-jong, jeu de go et autres loisirs. Paris: L’Harmattan; 2000.

Papineau E: Pathological gambling in Montreal’s Chinese community: An anthropological perspective. Journal of Gambling Studies 2005, 21: 157–178. 10.1007/s10899-005-3030-y

Papineau E: La prévention des problèmes liés au jeu: évolution, pratiques et acquis des autres dépendances. A l’heure de l’intégration des pratiques, Presses de l’Université Laval, Tabac, alcool, drogues, jeux de hasard et d’argent; 2009.

Paules X: Le fantan, une étude préliminaire (pp. 26–27). Paris: Congrès Réseau Asie; 2007.

Paules X: Gambling in China reconsidered: Fantan in South China during the early twentieth century. International Journal of Asian Studies 2010, 7: 179–200. 10.1017/S1479591410000069

Quotidien du peuple en ligne (Le): Chine: la lutte contre les jeux d’argent: l’année dernière porte ses fruits. 2008. http://forum.casinos-jackpots.net/asie/article2908.html

Reith G: Reflections on responsibility. Journal of Gambling Issues 2008, 22: 149–155.

Sader J: Le jeu au XXIème siècle, une distraction, un loisir, un anti dépresseur, une quête spirituelle ou « toutes ces réponses sont vrais. Colloque « La prévention des jeux de hasard à Montréal », Direction de santé publique de Montréal; 2005. http://www.dsp.santemontreal.qc.ca/fileadmin/documents/dossiers_thematiques/Jeunes/Jeux_de_hasard_et_d_argent/colloque_2005/jeu21e.pdf

Sin R: Gambling and problem gambling among the Chinese in Quebec: An exploratory study. Chinese Family Service of Greater Montreal, Quebec, Canada; 1997.

Skinner BF: Science and human behavior. Macmillan, New York; 1953.

Smith GJ, Wynne HJ: Measuring gambling and problem gambling in Alberta. Final report. Edmonton, AB: Alberta Gaming Research Institute; 2002. http://thesurvey.womenshealthdata.ca/pdf_files/gambling_alberta_cpgi.pdf

Sue R: Contribution à une sociologie historique du loisir. Cahiers Internationaux de Sociologie 1991., XCI:

Volberg RA, Gerstein DR, Christiansen EM, Baldridge J: Assessing self-reported expenditures on gambling. Managerial and Decision Economics 2001, 22: 77–96. 10.1002/mde.999

Vong F: The psychology of risk-taking in gambling among Chinese visitors to Macau. International Gambling Studies 2007, 7: 29–42. 10.1080/14459790601157731

Wan JM: The incentive to declare taxes and tax revenue: The lottery receipt experiment in China: Discussion Papers in Economics and Business 06–25, Osaka University, Graduate School of Economics and Osaka School of International Public Policy. http://ideas.repec.org/p/osk/wpaper/0625.html

Wei SJ: Personal communication to the author. 2000. 15 December 2000

Welte JW, Wieczorek WF, Barnes GM, Tidwell M-C, Hoffman JH: The relationship of ecological and geographic factors to gambling behavior and pathology. Journal of Gambling Studies 2004,20(4):405–423. 10.1007/s10899-004-4582-y

Wood RTA, Griffiths MD, Chappell D, Davies MNO: The structural characteristics of video games: A psycho-structural analysis. Cyberpsychology & Behavior 2004, 7: 1–10. 10.1089/109493104322820057

Wu YH, Gan SX: Analysis on China’s Lottery Economy. China Business Review 2003,2(4):21–27.

Xinhua News: China stipulates judicial interpretations on gambling. 2005. 15–05–05.http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/200505/14/eng20050514_184980.html 15-05-05.

Xu RS, Luo XB: Zhongguo gudai dubo xisu [China ancient gambling customs].. Shaanxi Renmin Chubanshe, Xian, People’s Republic of China; 1994.

Yang Y: Zhongguo youyi yanjiu [Research on Chinese entertainment] (1st ed., p. 96). . Shanghai: Shanghai Wenyi Chubanshe; 1990.

Yeh E, Hwe H, Lin T: Mental disorders in Taiwan: Epidemiological studies of community populations. In Chinese Societies and Mental Health. Edited by: Lin T, Tseng W, Yeh E. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press; 1995.

Zeng Z: Bounded Rationality and Lottery Consumption -A Study of lottery Players' Cognition for Winning Money. Journal of Macao Polytechnic Institute 2006. http://www.ipm.edu.mo/update/p_journal/2006/06_2/1.pdf

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Papineau, E. The expansion of electronic gambling machines in China through anthropological and public health lenses. Asian J of Gambling Issues and Public Health 3, 3 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/2195-3007-3-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2195-3007-3-3

) (Sin,

) (Sin, ) – a marketing bias likely to minimize the dangers of addiction to these games.

) – a marketing bias likely to minimize the dangers of addiction to these games. ) associated with very precise terminology on how to choose the entries for betting in several consecutive games” Paules,

) associated with very precise terminology on how to choose the entries for betting in several consecutive games” Paules,