Abstract

Background

Coincidence imaging of low-abundance yttrium-90 (90Y) internal pair production by positron emission tomography with integrated computed tomography (PET/CT) achieves high-resolution imaging of post-radioembolization microsphere biodistribution. Part 2 analyzes tumor and non-target tissue dose-response by 90Y PET quantification and evaluates the accuracy of tumor 99mTc macroaggregated albumin (MAA) single-photon emission computed tomography with integrated CT (SPECT/CT) predictive dosimetry.

Methods

Retrospective dose quantification of 90Y resin microspheres was performed on the same 23-patient data set in part 1. Phantom studies were performed to assure quantitative accuracy of our time-of-flight lutetium-yttrium-oxyorthosilicate system. Dose-responses were analyzed using 90Y dose-volume histograms (DVHs) by PET voxel dosimetry or mean absorbed doses by Medical Internal Radiation Dose macrodosimetry, correlated to follow-up imaging or clinical findings. Intended tumor mean doses by predictive dosimetry were compared to doses by 90Y PET.

Results

Phantom studies demonstrated near-perfect detector linearity and high tumor quantitative accuracy. For hepatocellular carcinomas, complete responses were generally achieved at D 70 > 100 Gy (D 70, minimum dose to 70% tumor volume), whereas incomplete responses were generally at D 70 < 100 Gy; smaller tumors (<80 cm3) achieved D 70 > 100 Gy more easily than larger tumors. There was complete response in a cholangiocarcinoma at D 70 90 Gy and partial response in an adrenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor metastasis at D 70 53 Gy. In two patients, a mean dose of 18 Gy to the stomach was asymptomatic, 49 Gy caused gastritis, 65 Gy caused ulceration, and 53 Gy caused duodenitis. In one patient, a bilateral kidney mean dose of 9 Gy (V 20 8%) did not cause clinically relevant nephrotoxicity. Under near-ideal dosimetric conditions, there was excellent correlation between intended tumor mean doses by predictive dosimetry and those by 90Y PET, with a low median relative error of +3.8% (95% confidence interval, -1.2% to +13.2%).

Conclusions

Tumor and non-target tissue absorbed dose quantification by 90Y PET is accurate and yields radiobiologically meaningful dose-response information to guide adjuvant or mitigative action. Tumor 99mTc MAA SPECT/CT predictive dosimetry is feasible. 90Y DVHs may guide future techniques in predictive dosimetry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Coincidence imaging of low-abundance yttrium-90 (90Y) internal pair production by 90Y positron emission tomography with integrated computed tomography (PET/CT) achieves high-resolution imaging of post-radioembolization microsphere biodistribution. In part 1, we reviewed the recent literature supporting the use of post-radioembolization 90Y PET/CT, described our scan protocol, patient cohort, diagnostic reporting guidelines, and results of qualitative analysis [1]. In brief, we showed that with proper diagnostic reporting technique and emphasis on continuity of care, the presence of background noise did not pose a problem and 90Y PET/CT consistently out-performed 90Y bremsstrahlung single-photon emission computed tomography with integrated CT (SPECT/CT) in all aspects of qualitative analysis [1].

The terms ‘predictive dosimetry’, ‘target’, ‘non-target’, ‘technical success’, and the ‘planning-therapy continuum’ were also defined in part 1 [1]. It is important for the understanding of part 2 to reiterate that our definition of technical success, an adaptation from conventional reporting standards [2], refers to the qualitative assessment of a satisfactory 90Y activity biodistribution in accordance with radiation planning expectations and should not be confused with ‘clinical success’ [2] which is quantitatively related to dose-response radiobiology.

A knowledge gap exists today between institutions which practice predictive dosimetry and others which rely on semi-empirical methods [3]. Readers who are accustomed to semi-empirical therapy planning may struggle to understand the dosimetric concepts discussed in this paper or its relevance to clinical practice. These readers are encouraged to refer to our recent series of publications explaining concepts in modern predictive dosimetry for 90Y resin microspheres and common misconceptions [3–6].

Where prognostication is of concern, qualitative analysis alone will not suffice [3]. The scientific language of dose-response radiobiology is the radiation absorbed dose expressed in grays (Gy), not the prescribed activity expressed in becquerels (Bq). To realize the full potential of post-radioembolization 90Y PET/CT, absorbed dose quantification should be performed in relevant clinical settings. As 90Y radioembolization is a brachytherapy delivered by β--emitting microspheres, any tissue response is expected to follow predictable dose-response radiobiology. In principle, accurate knowledge of radiation thresholds in both target and non-target tissue facilitates the optimization of predictive dosimetry and enables the prognostication of technically unsuccessful cases to guide adjuvant therapy or mitigative action to minimize non-target radiation toxicity.

However, accurate tissue radiation thresholds for 90Y resin microspheres have remained elusive despite more than two decades of clinical use. Current radiation planning limits are broad and quote mean absorbed doses which falsely assume a uniform dose distribution: tumor > 120 Gy, non-tumorous liver < 50 to 70 Gy, lungs < 20 to 30 Gy [7–9]. As a consequence of this uncertainty, dosimetric dilemmas may be encountered in patients who may benefit from radiation planning up to the limits of normal tissue radiation tolerance. Furthermore, normal tissue radiation thresholds for 90Y resin microspheres shunted to non-target viscera such as the stomach or duodenum are largely unknown, precluding informed decision making for appropriate mitigative action. Historically, research into dose-response data had been technically challenging: intraoperative beta probes or histological examinations are invasive [10, 11], quantification by 90Y bremsstrahlung scintigraphy is problematic and largely inaccurate [1], and predictive dosimetry simulated by 99mTc macroaggregated albumin (MAA) is subject to variable accuracy due to the physical limitations of MAA [12].

Dosimetric studies have shown 99mTc MAA to be feasible for simulating the post-radioembolization biodistribution of 90Y resin microspheres [13–16]. However, 99mTc MAA is an imperfect surrogate for 90Y resin microspheres. Due to biophysical and technical differences such as particle size, specific gravity, injected particle load, microembolization, and catheter placement, 99mTc MAA can never exactly replicate the post-radioembolization biodistribution of 90Y resin microspheres [12, 17]. Therefore, predictive dosimetry simulated by 99mTc MAA provides only an estimate of the tissue absorbed doses intended by the nuclear medicine physician [6]. Traditionally based on planar scintigraphy [13, 14], modern predictive dosimetry employs SPECT/CT to tomographically assess the biodistribution of 99mTc MAA and to improve its quantitative accuracy [6]. So far, the accuracy of 99mTc MAA SPECT/CT predictive dosimetry has only been indirectly validated by inference from follow-up response [6, 18, 19]. For technically successful cases without visually significant discordant biodistribution between 99mTc MAA and 90Y resin microspheres, a direct ‘Gy-to-Gy’ comparison of intended doses by 99mTc MAA SPECT/CT predictive dosimetry versus post-radioembolization doses by microsphere biodistribution analysis has not yet been performed to date.

Recent experimental and clinical studies have shown post-radioembolization 90Y PET quantification to be accurate and feasible [1, 20, 21]. 90Y PET/CT thus presents a new opportunity to study the radiobiology of 90Y resin microspheres in a rapid, convenient, and noninvasive manner, with the ability to tomographically evaluate the dose distribution of an entire target organ in high resolution by a single scan. Moreover, quantitative 90Y PET data can be translated into dose-volume histograms (DVHs) to dosimetrically account for the heterogeneous nature of microsphere biodistribution.

In part 2 of our two-part retrospective report, we focus on post-radioembolization 90Y PET quantification on the same patient cohort as was reported in part 1 [1]. We analyze dose-responses in tumor and non-target tissue using 90Y PET-based voxel dosimetry or Medical Internal Radiation Dose (MIRD) macrodosimetry [7, 22]. We describe the potential of 90Y DVHs to guide predictive dosimetry and discuss how the quantification of non-target absorbed doses may impact post-radioembolization care. Finally, we evaluate the accuracy of tumor 99mTc MAA SPECT/CT predictive dosimetry in direct comparison to post-radioembolization doses by 90Y PET.

Methods

Phantom quantification

An institutional review board approval was obtained for the conduct and publication of this retrospective report (CIRB 2010/781/C, SingHealth, Singapore). Verbal consent was obtained from patients for scans to be performed. Quantitative phantom studies were first performed to confirm detector linearity of our time-of-flight lutetium-yttrium-oxyorthosilicate (LYSO) system and for comparison with a radiopharmacy dose calibrator. 90Y resin microspheres (SIR-Spheres, Sirtex Medical Limited, North Sydney, Australia) were used. We scanned the microsphere sediment and not its fresh suspension to avoid issues with microsphere sedimentation during PET acquisition. In effect, each vial sediment represents a small heterogeneous volume of high 90Y radioconcentration, simulating a small tumor implanted with a high and heterogeneous density of 90Y resin microspheres. All microsphere sediments were scanned within its original glass shipping vial for convenience and to avoid operator radiation exposure for microsphere extraction.

Vials of microspheres were obtained by convenience sampling, either before or after extraction of the desired treatment activity. Phantom scans of high activities (>3.0 GBq) were performed on fresh vials on the day it was received from the manufacturer, while scans of very low activities (<0.1 GBq) were performed after a period of decay of residual vial activities. The vials were placed within a perspex body phantom and scanned in one bed position over 15 min (Figure 1). All scan parameters were identical to our clinical scan protocol described in part 1 [1].

Example of a 90 Y PET/ CT phantom scan with maximum intensity projection image. (a) Trans-axial, (b) coronal, and (c) sagittal planes. This scan shows our lowest tested vial sediment activity of 3.5 MBq (≈3 MBq/ml). The upper PET visual display threshold of this scan was adjusted to 114% (2,000 kBq/ml) to minimize visual interference from background noise [1]. (d) Maximum intensity projection image of the same phantom scan (arrow indicates vial sediment) with the upper PET visual display threshold adjusted to 1% (20 kBq/ml) to reveal the underlying background noise as an example to readers [1].

For vial activity quantification, a volume of interest (VOI) encompassing the entire vial sediment was generated by selecting a fixed volumetric isocontour threshold of 1%. The total 90Y activity (kBq) within the VOI was calculated as the product of its mean radioconcentration (kBq/ml) and its volume (cm3). Each vial sediment quantified by 90Y PET was compared to that measured by a dose calibrator (Biodex Atomlab 500, Biodex Medical Systems, New York, NY, USA). Its purpose was to evaluate the general relative accuracy of 90Y PET quantification in the absence of a true reference standard and also to empirically assess quantitative effects from background noise, variable vial sediment volume, radioconcentration, vial geometry, or positron contributions from possible radionuclidic impurities such as yttrium-88 [23].

Tissue quantification

Retrospective absorbed dose quantification by 90Y PET was performed on the same 23-patient data set as was reported in part 1 [1]. The two objectives were, first, to establish dose-response observations in tumor and non-target tissue and, second, to evaluate the accuracy of tumor 99mTc MAA SPECT/CT predictive dosimetry [6] in direct Gy-to-Gy comparison to post-radioembolization doses by 90Y PET.

Tumors were analyzed using cumulative 90Y DVHs generated by voxel dosimetry. This was performed on a small select group of tumors treated under highly favorable, near-ideal dosimetric conditions to ensure reliable dose-response observations and to assess the best possible accuracy of tumor 99mTc MAA SPECT/CT predictive dosimetry. The tumor selection criteria were as follows: technically successful 90Y radioembolization, well-circumscribed tumors with good overall activity coverage, mean tumor-to-normal liver (T/N) ratio ≥2 as estimated by 99mTc MAA SPECT/CT, and follow-up diagnostic sectional imaging available for clinical correlation. All tumor VOIs were manually contoured slice by slice according to CT anatomical margins. We avoided using tumor VOIs generated by PET volumetric isocontour thresholding as these often do not represent their true anatomical extent due to heterogeneous microsphere biodistribution. Regions of absent 90Y activity in tumors were visually correlated to CT findings and excluded from VOI analysis if necrotic.

90Y PET voxel dosimetry was performed by a novel program written in Interactive Data Language (IDL 6.1), freely available from the corresponding author for research purposes [24]. This program was initially developed for total glycolytic volume analysis of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET data [25], subsequently adapted for 90Y PET voxel dosimetry in this study. 90Y absorbed dose distributions were calculated using a simplified approach based on voxel mean radioconcentrations instead of dose kernel or Monte Carlo methods. Its dosimetric rationale and evidence to support this approach are detailed in Additional file 1.

The reconstructed 90Y PET voxels have a spatial resolution of approximately 10 to 12 mm at full width at half maximum. 90Y radiation cross fire and beta dose spread were taken to be similar to the blurring of activity due to the partial volume effect of PET. Although the dose contribution by 90Y bremsstrahlung may be assumed negligible within areas of 90Y activity [26], we accounted for such bremsstrahlung losses in our voxel dosimetry by adjusting our absorbed dose coefficient by a factor of 0.995 based on Monte Carlo calculations. 90Y dosimetric parameters used were as follows: half-life, 64.1 hours; energy per decay, 0.934 MeV [27]; absorbed dose coefficient, 49.59 Gy/GBq/kg; and soft tissue density, 1.04 g/cm3. The dosimetry assumes no post-implantation redistribution of microspheres, leaching, nor destruction of microspheres in vivo. Dose distribution heterogeneity was limited to the size of the reconstructed voxels; true dose heterogeneity at the microscopic level was not assessed.

Mean absorbed doses in tumor vascular thrombosis and gastric and duodenal walls were estimated by 90Y MIRD macrodosimetry [7, 22]. For these small or thin-walled structures, 90Y DVH analysis was not feasible due to partial volume effect and uncertainties in manual VOI delineation on CT. These issues especially affect hollow viscus, such as the stomach and duodenum, as variable wall distension or compression introduces further uncertainties in manual VOI delineation. Instead, we chose to generate VOIs by PET volumetric isocontour thresholding, visually constrained to CT anatomical margins. This obtains the mean VOI radioconcentration, from which the VOI-specific mean absorbed doses were approximated by MIRD formularism. dose-response analysis was strictly limited to observations within these VOIs.

All tissue absorbed doses were decay-corrected back to the time of 90Y radioembolization. Tumor response was reported using the lesion-specific modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors [28]. In addition, we defined a ‘minor response’ as any tumor size reduction which does not fulfill the criteria for a partial response. As there is no current standard for 90Y DVH reporting, we selected the D 70 and V 100 values for tumor reporting, where D 70 represents the minimum absorbed dose delivered to 70% of the tumor volume, and V 100 represents the percentage tumor volume receiving ≥100 Gy. Non-target absorbed doses were expressed in accordance to external beam radiotherapy convention as far as possible [29, 30]. Cases of non-target activity were followed up by retrospective review of clinical records, and relevant clinical toxicities were graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.03 (CTCAE; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

The second objective of retrospective absorbed dose quantification was to evaluate the accuracy of tumor predictive dosimetry simulated by 99mTc MAA SPECT/CT. This was performed by a direct, i.e., Gy-to-Gy, comparison between intended tumor mean doses and post-radioembolization tumor mean doses by 90Y PET, expressed as relative percentage errors. Our protocol for predictive dosimetry was previously described [6], which involves catheter-directed CT angiography for arterial territory delineation, quantitative 99mTc MAA SPECT/CT of the target organ, and MIRD macrodosimetry to achieve artery-specific personalized radiation planning for 90Y resin microspheres.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as median, mean, range, and 95% confidence intervals (CI), where applicable. Linear regression with Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) and Bland-Altman plots with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were used for comparison of quantitative data; a value of ≥0.8 indicated excellent correlation.

Results

Phantom validation

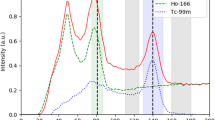

A total of 15 phantom scans were performed. Near-perfect detector linearity was demonstrated on our time-of-flight LYSO system within the tested limits of 3.5 MBq to 3.2 GBq (r = 0.99, calibration factor 0.99, Figure 2). Detector saturation was not a problem without 90Y bremsstrahlung shielding. The Bland-Altman plot showed excellent agreement between 90Y PET and dose calibrator measurements (ICC = 99.85%; Additional file 1: Figure S1).

Across all data points, the median relative quantification error of 90Y PET was +1.38% (mean +2.18%, 95% CI -3.92% to +8.28%). Vial activities >400 MBq had very low relative quantification errors (mean +0.29%, median +0.72%, 95% CI -3.30% to +3.87%), whereas vial activities <400 MBq had larger errors (mean +4.35%, median +4.95%, 95% CI -8.43% to +17.12%; Additional file 1: Figure S2) - a finding attributable to background noise from 176Lu within the LYSO crystal [31, 32]. Based on these results, we deemed it feasible to assume all tumor activities quantified by 90Y PET to have negligible error for the purposes of this study.

90Y dose-response

Twenty-three post-radioembolization 90Y PET/CT scans were eligible for dose-response analysis, as was reported in part 1 [1]. As per our institutional protocol, the catheter tip for 90Y resin microsphere injection was placed in exactly the same position as for 99mTc MAA injection in all cases, as visually assessed by the procedural interventional radiologist during 90Y radioembolization. Only eight patients fulfilled all tumor selection criteria: patients 1, 2, 8, 9, 17, 19, 21, and 23. The median tumor-to-normal liver (T/N) ratio estimated by 99mTc MAA SPECT/CT was 5.0 (mean 8.0, range 1.8 to 21.9). Tumor 90Y DVH dose-response results involving hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC), cholangiocarcinoma, and adrenal metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST; Figures 3 and 4) are presented in Table 1. Across HCCs of various lesion sizes, cross-analysis of seven 90Y DVHs suggest that complete responses were generally achieved at D 70 > 100 Gy, whereas tumors with incomplete responses generally have D 70 < 100 Gy (Figure 5). Smaller HCCs, such as those <80 cm3, achieved D 70 > 100 Gy more easily than larger tumors. dose-response results of portal vein tumor thrombosis by 90Y MIRD macrodosimetry (Figure 6) are presented in Table 2.

Patient 9. 90Y radioembolization of an organ other than the liver. KIT-negative GIST with bulky metastasis to the right adrenal gland, refractory to tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Angiography was previously shown in part 1 [1]. (a) Catheter-directed CT angiogram of the right inferior adrenal artery delineates the targeted right adrenal tumor measuring 10.1 × 6.3 cm. (b) Post-radioembolization 90Y PET/CT depicts microsphere biodistribution in high resolution, with concordant activity within targeted regions of contrast-enhancing tumor. Low-grade activity seen in the adjacent right liver lobe is due to 90Y radioembolization of a segment IV metastasis. (c) Isodose map by voxel dosimetry of the corresponding trans-axial slice of the right adrenal tumor provides a visual representation of dose heterogeneity within the tumor and adjacent right liver lobe and displays the full dose range from 0 to >1,000 Gy. (d) Follow-up contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen at 9.5 months shows a moderate size reduction to 7.6 × 4.6 cm, representing a partial response.

90 Y DVH of the right adrenal gland GIST metastasis generated by 90 Y PET voxel dosimetry. Continued from Figure 3. A partial response was achieved at D 70 53 Gy.

Patient 10. (a) Catheter-directed CT angiogram of the anterior branch of the right hepatic artery, supplying segments V and VIII, demonstrates contrast enhancement of a large portal vein tumor thrombus (arrow). (b, c) A 90Y PET VOI of the activity within the portal vein tumor thrombus was defined by volumetric isocontour thresholding, visually constrained to its anatomical margins as seen on the catheter-directed CT angiography. Within this VOI, the mean 90Y radioconcentration at the time of scan (5,239.8 kBq/ml) was decay-corrected back to the time of 90Y radioembolization (6,653 kBq/ml). By 90Y MIRD macrodosimetry, the mean absorbed dose of the portal vein tumor thrombus was approximately 316 Gy within the VOI. (d) Follow-up triphasic CT of the liver in the arterial phase at 4 months post-radioembolization demonstrates a complete lack of contrast enhancement within the VOI (arrow), suggesting a complete response and clinically validates the 90Y PET quantification.

All dose-response results of non-target tissue were serendipitously obtained in cases of unintended non-target shunting of 90Y resin microspheres due to unexpected vascular stasis and microsphere reflux during 90Y radioembolization. The dose-response of the stomach (Figure 7) and proximal duodenum by 90Y MIRD macrodosimetry are presented in Table 3. 90Y DVH dose-response of the right kidney is presented in Table 4. All results were in keeping with published experiences of external beam radiotherapy [29, 30].

Patient 17. Non-target 90Y activity along the gastric greater curve causing CTCAE grade 3 toxicity [1]. A 90Y PET VOI of the activity along the gastric greater curve was defined by volumetric isocontour thresholding, visually constrained to its CT anatomical margins, shown here in (a) trans-axial, (b) coronal, and (c) sagittal planes. Within this VOI, the mean 90Y radioconcentration at the time of scan (813.1k Bq/ml) was decay-corrected back to the time of 90Y radioembolization (1,021.5 kBq/ml). By 90Y MIRD macrodosimetry, the non-target mean absorbed dose to the gastric greater curve was approximately 49 Gy within the VOI. Gastroscopy and biopsy findings were reported in part 1 [1].

Accuracy of tumor predictive dosimetry

Within the statistical limitations of our small data set of HCCs treated under near-ideal dosimetric conditions, the Bland-Altman plot of intended tumor mean doses versus post-radioembolization doses by 90Y PET showed excellent correlation (ICC = 97.68%; Additional file 1: Figure S3). Tumor 99mTc MAA SPECT/CT predictive dosimetry had a low median relative error of +3.8% (mean +6.0%, 95% CI -1.2% to +13.2%; Additional file 1: Figure S4) compared to 90Y PET. There may be a tendency for tumor predictive dosimetry to slightly overestimate the post-radioembolization tumor mean dose. There was no correlation between relative errors and mean T/N ratios (r = 0.05). Results are summarized in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Discussion

With its superior image resolution and quantitative capability, 90Y PET/CT is a powerful tool to be integrated into the 90Y radioembolization workflow. Quantitatively, as bland microembolization by 90Y resin microspheres has negligible biological effect [33], clinical outcomes or toxicities in both target and non-target tissue may be predicted from dose-response radiobiology quantified by 90Y PET, guiding appropriate adjuvant or mitigative action.

We have reported some of the earliest 90Y dose-response results for resin microspheres expressed in the form of DVHs. Our threshold of D 70 > 100 Gy for HCC complete response is consistent with post-radioembolization DVH case examples of HCC and melanoma liver metastasis shown by Strigari and D’Arienzo et al., respectively [34, 35]. 90Y DVHs are able to account for the heterogeneous nature of microsphere biodistribution and are scientifically superior to MIRD macrodosimetry which falsely assumes a uniform dose distribution. dose-response data from 90Y DVHs have the potential to guide future improvements in predictive dosimetry such as 99mTc MAA SPECT/CT-based DVHs with isodose maps to plan safer and more effective 90Y radioembolization [36]. For example, our data suggest that HCC tumor outcomes may be optimized by escalating the injected 90Y activity to achieve an intended tumor dose of D 70 > 100 Gy simulated by 99mTc MAA SPECT/CT DVH, within safety limitations to the lungs and non-tumorous liver.

For non-target activity, we observed that a mean absorbed dose of 18 Gy to the stomach was asymptomatic, while ≥49 Gy to the stomach or duodenum led to CTCAE grade 3 toxicity. Quantification of non-target absorbed doses by 90Y PET effectively translates subjective, qualitative information into objective and radiobiologically meaningful data to guide post-radioembolization care. This may involve close follow-up, extended use of proton pump inhibitors, surveillance endoscopy, or a trial of radioprotecting agents. For the kidney, we observed that a combined bilateral mean dose of 9 Gy (V 20 8%) did not result in any clinically relevant nephrotoxicity. This finding has clinical implications for the planning of safe kidney-directed 90Y radioembolization for renal malignancies [37, 38]. We were unable to define the exact normal tissue radiation thresholds based on our limited case series. However, greater clarity on this issue shall be gained in the years ahead as post-radioembolization 90Y PET/CT gains popularity around the world.

In this retrospective report, we have shown tumor 99mTc MAA SPECT/CT predictive dosimetry to be feasible within a small, highly select data set. Prospective validation trials on tumor predictive dosimetry are now needed, using 90Y PET-based absorbed doses as a reference. Our tumor dose-response results are only orientating and should be further validated by greater patient numbers and by using more adequate tumor response end points. It should also be noted that our dose-response results for both target and non-target tissue may not necessarily be valid for 90Y glass microspheres due to different physical characteristics.

We did not perform absorbed dose quantification of the non-tumorous liver or lungs as these are regions of much lower 90Y radioconcentration which may require further research and technical considerations on its quantitative accuracy by 90Y PET [39]. However, Elschot et al. have recently shown that 90Y PET-based DVHs of the non-tumorous liver may be feasible [40]. To date, there is no published data on the use of 90Y PET for post-radioembolization lung dose quantification. Nevertheless, we recognize the importance of tissue radiobiology in non-tumorous liver and lungs for the safe and effective clinical application of predictive dosimetry in 90Y radioembolization. This should be explored in future 90Y PET-based dosimetry research.

The specific aim of our tumor analysis was to evaluate the best possible performance of tumor predictive dosimetry planned by 99mTc MAA SPECT/CT. We are therefore limited by our study design to restrict our discussion only to the tumor aspect of predictive dosimetry; our study cannot draw conclusions on predictive dosimetry applied to non-tumorous liver or lungs. To this end, we have shown in our highly select tumor data set that the intended tumor mean doses by 99mTc MAA SPECT/CT predictive dosimetry correlated well with post-radioembolization doses by 90Y PET. From a clinical perspective, this means that if tumor predictive dosimetry had been applied to a technically successful 90Y radioembolization under near-ideal dosimetric conditions, then the intended tumor mean doses may be assumed valid and retrospective tumor dose quantification is usually unnecessary, unless for research or quality assurance.

In less ideal dosimetric conditions, tumor predictive dosimetry may be of variable accuracy, and retrospective tumor dose quantification by 90Y PET may be an option at the discretion of the nuclear medicine physician, e.g., MIRD-based predictive dosimetry applied to massive tumors with large heterogeneous areas of relative hypovascularity, where its assumption of a uniform activity biodistribution risks dosimetric uncertainty; or MIRD-based tumor predictive dosimetry applied to intended radiomicrosphere lobectomy or segmentectomy, where potential vascular stasis and reflux introduces dosimetric uncertainty. However, in technically unsuccessful90Y radioembolization, we feel that retrospective tumor dose quantification by 90Y PET may be routinely indicated because the intended tumor doses by predictive dosimetry may have become invalid. Furthermore, non-target activity may also be present. In such situations, the prognosis remains uncertain unless retrospective dose quantification is performed within appropriate regions of interest.

90Y PET/CT is but one component near the end of the entire planning-therapy continuum. 90Y PET/CT is a descriptive modality to assess post-implantation microsphere biodistribution, where all inadvertent or adverse findings have already irreversibly occurred. To the nuclear medicine physician, the component of the planning-therapy continuum with the greatest prognostic impact, but also more complex, is predictive dosimetry. In principle, 90Y radioembolization planned by predictive dosimetry is not subject to prognostic uncertainties experienced by semi-empirical 90Y activity prescription, a common practice within the medical oncology paradigm. In the modern era of personalized medicine, predictive dosimetry planned by modern tomographical techniques give nuclear medicine physicians unprecedented insight into the achievable outcomes for every 90Y radioembolization [6]. Technical success does not necessarily imply clinical success: the former is a qualitative assessment of microsphere biodistribution; the latter is a quantitative function of dose-response radiobiology. While interventional radiologists do their utmost to achieve technical success, it is the responsibility of the nuclear medicine physician to ensure that their efforts can be translated into clinical success by the rigorous application of predictive dosimetry.

Conclusions

Qualitative and quantitative post-radioembolization 90Y PET/CT are two sides of the same coin and must be interpreted in the context of each other, never in isolation. Tumor and non-target tissue absorbed dose quantification by 90Y PET is accurate and yields radiobiologically meaningful dose-response information to guide adjuvant or mitigative action. Intended tumor mean doses by 99mTc MAA SPECT/CT predictive dosimetry correlated well with post-radioembolization doses by 90Y PET. 90Y DVHs have the potential to guide future techniques in predictive dosimetry. Continued research into predictive dosimetry promises abundant rewards for safer and more effective 90Y radioembolization, especially as it expands into organs other than the liver.

References

Kao YH, Steinberg JD, Tay YS, Lim GKY, Yan J, Townsend DW, Takano A, Burgmans MC, Irani FG, Teo TKB, Yeow TN, Gogna A, Lo RHG, Tay KH, Tan BS, Chow PKH, Satchithanantham S, Tan AEH, Ng DCE, Goh ASW: Post-radioembolization yttrium-90 PET/CT - part 1: diagnostic reporting. EJNMMI Res 2013, 3: 56. 10.1186/2191-219X-3-56

Salem R, Lewandowski RJ, Gates VL, Nutting CW, Murthy R, Rose SC, Soulen MC, Geschwind JF, Kulik L, Kim YH, Spreafico C, Maccauro M, Bester L, Brown DB, Ryu RK, Sze DY, Rilling WS, Sato KT, Sangro B, Bilbao JI, Jakobs TF, Ezziddin S, Kulkarni S, Kulkarni A, Liu DM, Valenti D, Hilgard P, Antoch G, Muller SP, Alsuhaibani H, et al.: Research reporting standards for radioembolization of hepatic malignancies. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2011, 22: 265–278. 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.10.029

Kao YH: Results confounded by a disregard for basic dose-response radiobiology. J Nucl Med 2013. 10.2967/jnumed.113.122846

Kao YH, Tan EH, Ng CE, Goh SW: Clinical implications of the body surface area method versus partition model dosimetry for yttrium-90 radioembolization using resin microspheres: a technical review. Ann Nucl Med 2011, 25: 455–461. 10.1007/s12149-011-0499-6

Kao YH, Tan EH, Teo TK, Ng CE, Goh SW: Imaging discordance between hepatic angiography versus Tc-99m-MAA SPECT/CT: a case series, technical discussion and clinical implications. Ann Nucl Med 2011, 25: 669–676. 10.1007/s12149-011-0516-9

Kao YH, Hock Tan AE, Burgmans MC, Irani FG, Khoo LS, Gong Lo RH, Tay KH, Tan BS, Hoe Chow PK, Eng Ng DC, Whatt Goh AS: Image-guided personalized predictive dosimetry by artery-specific SPECT/CT partition modeling for safe and effective 90 Y radioembolization. J Nucl Med 2012, 53: 559–566. 10.2967/jnumed.111.097469

Dezarn WA, Cessna JT, DeWerd LA, Feng W, Gates VL, Halama J, Kennedy AS, Nag S, Sarfaraz M, Sehgal V, Selwyn R, Stabin MG, Thomadsen BR, Williams LE, Salem R, American Association of Physicists in Medicine: Recommendations of the American Association of Physicists in Medicine on dosimetry, imaging, and quality assurance procedures for 90 Y microsphere brachytherapy in the treatment of hepatic malignancies. Med Phys 2011, 38: 4824–4845. 10.1118/1.3608909

Lau WY, Kennedy AS, Kim YH, Lai HK, Lee RC, Leung TW, Liu CS, Salem R, Sangro B, Shuter B, Wang SC: Patient selection and activity planning guide for selective internal radiotherapy with yttrium-90 resin microspheres. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012, 82: 401–407. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.08.015

Giammarile F, Bodei L, Chiesa C, Flux G, Forrer F, Kraeber-Bodere F, Brans B, Lambert B, Konijnenberg M, Borson-Chazot F, Tennvall J, Luster M, Therapy, Oncology and Dosimetry Committees: EANM procedure guideline for the treatment of liver cancer and liver metastases with intra-arterial radioactive compounds. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2011, 38: 1393–1406. 10.1007/s00259-011-1812-2

Lau WY, Leung TW, Ho S, Chan M, Leung NW, Lin J, Metreweli C, Li AK: Diagnostic pharmaco-scintigraphy with hepatic intra-arterial technetium-99m macroaggregated albumin in the determination of tumour to non-tumour uptake ratio in hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Radiol 1994, 67: 136–139. 10.1259/0007-1285-67-794-136

Kennedy AS, Nutting C, Coldwell D, Gaiser J, Drachenberg C: Pathologic response and microdosimetry of 90 Y microspheres in man: review of four explanted whole livers. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2004, 60: 1552–1563. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.09.004

Van de Wiele C, Maes A, Brugman E, D’Asseler Y, De Spiegeleer B, Mees G, Stellamans K: SIRT of liver metastases: physiological and pathophysiological considerations. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2012, 39: 1646–1655. 10.1007/s00259-012-2189-6

Ho S, Lau WY, Leung TW, Chan M, Ngar YK, Johnson PJ, Li AK: Partition model for estimating radiation doses from yttrium-90 microspheres in treating hepatic tumours. Eur J Nucl Med 1996, 23: 947–952. 10.1007/BF01084369

Ho S, Lau WY, Leung TW, Chan M, Johnson PJ, Li AK: Clinical evaluation of the partition model for estimating radiation doses from yttrium-90 microspheres in the treatment of hepatic cancer. Eur J Nucl Med 1997, 24: 293–298.

Flamen P, Vanderlinden B, Delatte P, Ghanem G, Ameye L, Van Den Eynde M, Hendlisz A: Multimodality imaging can predict the metabolic response of unresectable colorectal liver metastases to radioembolization therapy with yttrium-90 labeled resin microspheres. Phys Med Biol 2008, 53: 6591–6603. 10.1088/0031-9155/53/22/019

Campbell JM, Wong CO, Muzik O, Marples B, Joiner M, Burmeister J: Early dose response to yttrium-90 microsphere treatment of metastatic liver cancer by a patient-specific method using single photon emission computed tomography and positron emission tomography. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009, 74: 313–320. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.12.058

Jiang M, Fischman A, Nowakowski FS, Heiba S, Zhuangyu Z, Knesaurek K, Weintraub J, Machac J: Segmental perfusion differences on paired Tc-99m macroaggregated albumin (MAA) hepatic perfusion imaging and yttrium-90 (Y-90) bremsstrahlung imaging studies in SIR-Sphere radioembolization: associations with angiography. J Nucl Med Radiat Ther 2012, 3: 122.

Chiesa C, Maccauro M, Romito R, Spreafico C, Pellizzari S, Negri A, Sposito C, Morosi C, Civelli E, Lanocita R, Camerini T, Bampo C, Bhoori S, Seregni E, Marchianò A, Mazzaferro V, Bombardieri E: Need, feasibility and convenience of dosimetric treatment planning in liver selective internal radiation therapy with (90)Y microspheres: the experience of the National Tumor Institute of Milan. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2011, 55: 168–197.

Garin E, Lenoir L, Rolland Y, Edeline J, Mesbah H, Laffont S, Porée P, Clément B, Raoul JL, Boucher E: Dosimetry based on 99m Tc-macroaggregated albumin SPECT/CT accurately predicts tumor response and survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with 90 Y-loaded glass microspheres: preliminary results. J Nucl Med 2012, 53: 255–263. 10.2967/jnumed.111.094235

Lhommel R, van Elmbt L, Goffette P, Van den Eynde M, Jamar F, Pauwels S, Walrand S: Feasibility of 90 Y TOF PET-based dosimetry in liver metastasis therapy using SIR-Spheres. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2010, 37: 1654–1662. 10.1007/s00259-010-1470-9

Walrand S, Lhommel R, Goffette P, Van den Eynde M, Pauwels S, Jamar F: Hemoglobin level significantly impacts the tumor cell survival fraction in humans after internal radiotherapy. EJNMMI Res 2012, 2: 20. 10.1186/2191-219X-2-20

Gulec SA, Mesoloras G, Stabin M: Dosimetric techniques in 90 Y-microsphere therapy of liver cancer: the MIRD equations for dose calculations. J Nucl Med 2006, 47: 1209–1211.

Selwyn R, Micka J, DeWerd L, Nickles R, Thomadsen B: Technical note: the calibration of 90 Y-labeled SIR-Spheres using a nondestructive spectroscopic assay. Med Phys 2008, 35: 1278–1279. 10.1118/1.2889621

Boucek JA, Kao YH, Francis RJ: Yttrium-90 PET/CT voxel dosimetry. Western Australia, Australia: Department of Nuclear Medicine, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital; 2012.

Boucek JA, Francis RJ, Jones CG, Khan N, Turlach BA, Green AJ: Assessment of tumour response with (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography using three-dimensional measures compared to SUVmax - a phantom study. Phys Med Biol 2008, 53: 4213–4230. 10.1088/0031-9155/53/16/001

Stabin MG, Eckerman KF, Ryman JC, Williams LE: Bremsstrahlung radiation dose in yttrium-90 therapy applications. J Nucl Med 1994, 35: 1377–1380.

Browne E, Firestone RB: Table of Radioactive Isotopes. New York: Wiley; 1986.

Lencioni R, Llovet JM: Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis 2010, 30: 52–60. 10.1055/s-0030-1247132

Marks LB, Yorke ED, Jackson A, Ten Haken RK, Constine LS, Eisbruch A, Bentzen SM, Nam J, Deasy JO: Use of normal tissue complication probability models in the clinic. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010,76(Suppl):S10-S19.

Kavanagh BD, Pan CC, Dawson LA, Das SK, Li XA, Ten Haken RK, Miften M: Radiation dose-volume effects in the stomach and small bowel. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010,76(Suppl):S101-S107.

Carlier T, Eugène T, Bodet-Milin C, Garin E, Ansquer C, Rousseau C, Ferrer L, Barbet J, Schoenahl F, Kraeber-Bodéré F: Assessment of acquisition protocols for routine imaging of Y-90 using PET/CT. EJNMMI Res. 2013, 3: 11. 10.1186/2191-219X-3-11

Walrand S, Jamar F, van Elmbt L, Lhommel R, Bekonde EB, Pauwels S: 4-Step renal dosimetry dependent on cortex geometry applied to 90 Y peptide receptor radiotherapy: evaluation using a fillable kidney phantom imaged by 90 Y PET. J Nucl Med 2010, 51: 1969–1973. 10.2967/jnumed.110.080093

Bilbao JI, de Martino A, de Luis E, Díaz-Dorronsoro L, Alonso-Burgos A, Martínez de la Cuesta A, Sangr B, García de Jalón JA: Biocompatibility, inflammatory response, and recannalization characteristics of nonradioactive resin microspheres: histological findings. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2009, 32: 727–736. 10.1007/s00270-009-9592-9

Strigari L, Sciuto R, Rea S, Carpanese L, Pizzi G, Soriani A, Iaccarino G, Benassi M, Ettorre GM, Maini CL: Efficacy and toxicity related to treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with 90 Y-SIR spheres: radiobiologic considerations. J Nucl Med 2010, 51: 1377–1385. 10.2967/jnumed.110.075861

D’Arienzo M, Chiaramida P, Chiacchiararelli L, Coniglio A, Cianni R, Salvatori R, Ruzza A, Scopinaro F, Bagni O: 90 Y PET-based dosimetry after selective internal radiotherapy treatments. Nucl Med Commun 2012, 33: 633–640. 10.1097/MNM.0b013e3283524220

Dieudonné A, Garin E, Laffont S, Rolland Y, Lebtahi R, Leguludec D, Gardin I: Clinical feasibility of fast 3-dimensional dosimetry of the liver for treatment planning of hepatocellular carcinoma with 90 Y-microspheres. J Nucl Med 2011, 52: 1930–1937. 10.2967/jnumed.111.095232

Sirtex Technology Pty Ltd: Pilot study of selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT) with yttrium-90 resin microspheres (SIR-Spheres microspheres) in patients with renal cell carcinoma (STX0110, “RESIRT”). Trial ID ACTRN1261000069005. http://australiancancertrials.gov.au/

Hamoui N, Gates VL, Gonzalez J, Lewandowski RJ, Salem R: Radioembolization of renal cell carcinoma using yttrium-90 microspheres. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2013, 24: 298–300. 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.10.027

Goedicke A, Berker Y, Verburg F, Behrendt F, Winz O, Mottaghy F: Study-parameter impact in quantitative 90-yttrium PET imaging for radioembolization treatment monitoring and dosimetry. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2013, 32: 485–492.

Elschot M, Vermolen BJ, Lam MG, de Keizer B, van den Bosch MA, de Jong HW: Quantitative comparison of PET and bremsstrahlung SPECT for imaging the in vivo yttrium-90 microsphere distribution after liver radioembolization. PLoS One 2013, 8: e55742. 10.1371/journal.pone.0055742

Acknowledgements

We thank the following individuals for their contributions: Dr Glenn P. Sy, M.D., Clinical Application Specialist, GE Healthcare ASEAN, for assisting with the 90Y PET/CT optimization; Miss Toh Ying, Research Coordinator, Department of Nuclear Medicine and PET, Singapore General Hospital, for the administrative support; Dr Terence Teo Kiat Beng, Dr Yeow Tow Non, and Dr Apoorva Gogna, Interventional Radiologists, Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Singapore General Hospital, for performing the 90Y radioembolization of the patients in this report; Miss Doreen Lau Ai Hui and Dr Kei Pin Lin, Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Singapore General Hospital, for providing the CT images; and Dr Choo Su Pin, Medical Oncologist, Department of Medical Oncology, National Cancer Centre Singapore, for patient referrals and reviewing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

YHK, ASWG, KHT, and PKHC received research funding from Sirtex Medical Singapore. ASWG and PKHC received honoraria from Sirtex Medical Singapore. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YHK, YST, GKYL, SS, AEHT, DCEN, and ASWG were involved in the study design, implementation, analysis, and manuscript preparation. JDS, JY, and DWT were involved in the study design, scan optimization, and manuscript preparation. CB, JAB, RJF, and TSTC were involved in the data analysis and manuscript preparation. PKHC was involved in the clinical care and manuscript preparation. MCB, FGI, RHGL, KHT, and BST were involved in the radioembolization, angiographic analysis, and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

13550_2013_156_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Additional file 1: Online resource including four additional figures ( Figure S1, S2, S3 , S4) and a table ( Table S1). (PDF 393 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kao, YH., Steinberg, J.D., Tay, YS. et al. Post-radioembolization yttrium-90 PET/CT - part 2: dose-response and tumor predictive dosimetry for resin microspheres. EJNMMI Res 3, 57 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/2191-219X-3-57

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2191-219X-3-57