Abstract

Shift work and overtime have been implicated as important work-related risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD). Many firefighters who contractually work on a 24-hr work schedule, often do overtime (additional 24-hr shifts) which can result in working multiple, consecutive 24-hr shifts. Very little research has been conducted on firefighters at work that examines the impact of performing consecutive 24-hr shifts on cardiovascular physiology. Also, there have been no standard field methods for assessing in firefighters the cardiovascular changes that result from 24-hr shifts, what we call “cardiovascular strain”. The objective of this study, as the first step toward elucidating the role of very long (> 48 hrs) shifts in the development of CVD in firefighters, is to develop and describe a theoretical framework for studying cardiovascular strain in firefighters on very long shifts (i.e., > 2 consecutive 24-hr shifts). The developed theoretical framework was built on an extensive literature review, our recently completed studies with firefighters in Southern California, e-mail and discussions with several firefighters on their experiences of consecutive shifts, and our recently conducted feasibility study in a small group of firefighters of several ambulatory cardiovascular strain biomarkers (heart rate, heart rate variability, blood pressure, salivary cortisol, and salivary C-reactive protein). The theoretical framework developed in this study will facilitate future field studies on consecutive 24-hr shifts and cardiovascular health in firefighters. Also it will increase our understanding of the mechanisms by which shift work or long work hours can affect CVD, particularly through CVD biological risk factors, and thereby inform policy about sustainable work and rest schedules for firefighters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There are almost 1.2 million professional and voluntary firefighters in the United States (US) [1]. Firefighters have a high risk for on-duty cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality [2, 3] and have a high prevalence of CVD biological risk factors (obesity, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia) [2–6]. Working consecutive 24-hr shifts, a combination of 24-hr shift work and overtime (another 24-hr shifts), is common [4, 6, 7] among US firefighters. However, very little research has been conducted on firefighters at work that examines the impact of performing consecutive 24-hr shifts on their cardiovascular physiology. Also there have been few established physiological methods for assessing cardiovascular strain in firefighter on consecutive 24-hr shifts. The objective of this study, as the first step toward elucidating the role of very long (> 48 hrs) shifts in the development of CVD in firefighters, is to develop and describe a theoretical framework for studying cardiovascular strain in firefighters on very long shifts (i.e., > 2 consecutive 24-hr shifts).

Review

Consecutive 24-hr Shifts among Firefighters

According to the 2010 firefighter fatality report of the US Fire Administration, sudden cardiac death accounts for 49% of total firefighter fatalities at work. The reasons for these increased fatalities are not well understood and we believe there may be important unidentified or understudied occupational determinants of CVD risk factors contributing to CVD mortality in firefighters. Shift work and overtime (additional 24-hr shifts) are very common among firefighters in the US [4, 6, 7] and have been implicated as important work-related risk factors of CVD in firefighters [5, 8] based on the literature on shift work or long work hours and CVD in general or among other working populations.

Firefighters usually work a 24-hr shift schedule (e.g., the Kelly schedule: On/Off/On/Off/On/Off/Off/Off/Off; a modified Kelly schedule; or a 48-hr work on and 96-hr off schedule: On/On/Off/Off/Off/Off). However, many firefighters do additional 24-hr shifts beyond their standard work schedule (10-11 shifts per month) (for example, see Table 1). Overtime can be voluntary or mandatory, and is due to a constant staffing policy – “staffing an operation with just enough positions to cover all seats – leaves and vacancies are covered with overtime assignments” [9]. This policy frequently results in firefighters working multiple consecutive 24-hr work shifts per month. A recent nationwide survey on firefighter departmental regulations regarding consecutive work hour limits among 37 fire departments in the US [7] indicated that the majority of fire departments (62%) allowed firefighters to do shifts of 72 or more consecutive work hours: many have no limit to the number of consecutive shifts (35%); while some have a 72 work hour limit (24%); or a 96 work hour limit (3%). In our recent survey of 365 firefighters [4, 10] who were employed at a fire department in Southern California, firefighters worked on average thirteen 24-hr shifts per month which is 2–3 more shifts per month than required by contract. Moreover, a substantial number of firefighters, 67%, worked 72 consecutive hours, while 26% worked 96 consecutive hours at least one time per month. On a typical 24-hr shift, firefighters can sleep at night at the fire station, but they can be frequently woken for emergency calls.

A number of occupations already have nationwide regulations on work and rest schedules, such as drivers (continuous driving time, ≤10 hrs) [11], young doctors (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, continuous working time, ≤ 30 hrs) [12], and ambulance workers (American Ambulance Association, continuous working time, ≤ 36 hrs) [7]. But firefighters do not have one, in part, because there is as yet insufficient evidence of the potential harm of such work schedules for firefighters.

Little is known about the impact of consecutive 24-hr shifts on the health of firefighters

Despite numerous epidemiological studies [13–15] on the causes of CVD-related mortality in firefighters, no studies have specifically examined the impact of consecutive 24-hr shifts on CVD or CVD biological risk factors in firefighters. One study [16] reported that sick leave, work-related injury, and motor vehicle accident rates were higher among firefighters on the 2nd 24-hr shift than on the 1st 24-hr shift. Only two studies [17, 18] examined the association between 24-hr shifts and mental health among firefighters. Saijo et al. [17] reported that there was no significant association between the number of 24-hr shifts per month (11–13 times vs. 8–10 times) and depression symptoms in 1,301 firefighters. However, the authors reported higher (albeit not statistically significant) depression symptoms in firefighters who reported longer extra hours per month (4–33 hrs vs. 0–3 hrs). In our study, we found higher self-reported exhaustion on the Maslach Burnout Inventory [19] among firefighters in Southern California doing frequent three consecutive 24-hr shifts per month [18]. Depression and exhaustion have been suggested as possible CVD risk factors [20, 21] that could disturb several internal physiological systems (e.g., autonomic nervous system, hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and systematic inflammation process).

Three NIOSH firefighter fatality reports [22–24] investigated sudden death cases which occurred in the milieu of consecutive 24-hr shifts and NIOSH proposed to limit the number of consecutive shifts that a firefighter can work for preventing on-duty sudden cardiac death among firefighters based on the literature in other working populations that shift work and long work hours may impact on CVD [25, 26]. Although one may infer from the above studies that consecutive 24-hr shifts increase the risk of CVD among firefighters, there is as yet no strong evidence that multiple consecutives 24-hr shifts are associated with CVD risk factors or with cardiovascular strain and CVD in firefighters.

Two critical barriers to progress in research on cardiovascular strain in firefighters on very long shifts

One critical barrier to progress in research on cardiovascular strain in firefighters is the lack of a well-designed field study that examines day-to-day changes in cardiovascular parameters in firefighters working consecutive shifts. Conduct of such a field study has been recommended to determine whether there is an association between long work hours and health-related outcomes [27] mediated by cardiovascular mechanisms. Also it is well known that a within-subject study design, i.e., repeated measures in a subject over time, has merits over a between-subject study in that it has more statistical power (smaller sample size needed for study) and is more effective in controlling for individual differences in coping and physiological responses to environmental stressors [27–29] because the participants act as their own control group.

Another critical barrier to progress is the lack of standard methods for assessing the accumulation of cardiovascular strain in firefighters over consecutive 24-hr shifts. Strain is defined here as the internal responses of the organisms to external stimuli (e.g. work stressors) in accordance with the classical stress–strain workload model [30, 31]. More specifically, cardiovascular strain is defined as the physiological responses of the cardiovascular system (heart and blood vessels) to external stimulus. It can be detected by measuring the stimulus-induced changes in a number of physiological parameters related to the control of the cardiovascular system, either directly (e.g., heart rate and blood pressure) or indirectly (e.g., cortisol [32] and C-reactive protein (CRP) [33]. Heart rate [34–38], heart rate variability [39, 40], and blood pressure [41–43] are well-known CVD risk factors that have been used for decades in occupational ergonomics for assessing cardiovascular strain resulting from dynamic physical work [30] or mental workload [29]. Heart rate and blood pressure are also linearly associated with CV events [36, 44]. However, it has never been fully tested whether those and other promising measures (e.g., heart rate variability or salivary cortisol) can be used as “sub-clinical” biomarkers to assess cardiovascular strain accumulating over consecutive 24-hr shifts in firefighters. A few physiological studies [45–48] have shown a significant increase in heart rate when a firefighter responds to a call and also demonstrated a significant increase in heart rate variability when a favorable (fatigue-reducing) work schedule was introduced at night, but none of them extended their assessment beyond one 24-hr shift for the purpose of measuring the impact of consecutive shifts in firefighters. Also, no standard tests are available for assessing cardiovascular strain in firefighters in the wellness and fitness (WEFIT) medical programs implemented by many fire departments in the US (for details, http://www.iaff.org/HS/Well/wellness.html). The treadmill or cycle ergometer test in WEFIT medical programs is designed to estimate the maximal aerobic power (VO2 max) of firefighters and it is a good indicator of the physical working capacity or fitness of a firefighter. But it is limited in predicting or estimating cardiovascular strain in firefighters. About 30-40% of the VO2max of a worker has been used as an acceptable physical workload in occupational ergonomics [49–51]; however, the cut-point of 30-40% of VO2max is determined based on the assumption that a worker does physical tasks for 8 hours a day. Wu et al. [51] demonstrated that “long-hour shifts (> 10 hr) should assign a lower work intensity than for an 8-hr workday”. In addition, firefighters are not only exposed to variable amounts of physical work demands, but also numerous psychosocial mental demands at work [4, 5], so their total workload also cannot be determined based on a physical workload measure alone.

A feasibility study with several ambulatory biomarkers of cardiovascular strain

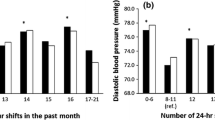

We recently recruited a group of firefighters (N = 7) in Southern California for a feasibility study of measuring several cardiovascular strain biomarkers (heart rate, heart rate variability, blood pressure, saliva cortisol, and saliva CRP) while they were doing 3 consecutive 24-hr shifts. We used recent, technologically-advanced, non-invasive instruments (a Polar S810 heart rate monitor, an Omron HEM-670 wrist blood pressure monitor, and Salimetric salivary cortisol and CRP test kits) for the data collection of the biomarkers and a short diary for the data collection of self-reported fatigue and distress. The data were collected at fire stations on the 1st and 3rd (not 2nd shift for simplicity) 24-shifts during 3 consecutive 24-hr shifts being completed by each of seven firefighters. The protocol of the feasibility study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, Irvine (HS# 2011-8426).

We chose five key physiological parameters that should be examined as “sub-clinical” biomarkers to assess cardiovascular strain accumulating over consecutives shifts in firefighters. The decision was made based on 1) the relevance of the parameters to CVD: all of the 5 parameters - heart rate [34–38], heart rate variability [39, 40], blood pressure [41–43], cortisol [52, 53], and C-reactive protein [54] have been reported as important CVD risk factors, and 2) the diverse physiological functions that the parameters indicate, considering the physiological mechanisms by which consecutive shifts could affect CVD. The Polar S810 heart rate monitor can measure not only heart rate, but also heart rate (beat-to-beat) variability with a resolution of 1 ms [55]. It is less expensive and simpler (no shaving, easier in detaching and reattaching when needed, and auto HR and HRV artifact correction functions) compared to a traditional ambulatory electrocardiogram (ECG) monitor (a Polar Holter monitor). The Polar S810 heart rate monitor was validated against an ECG monitors by several investigators [55, 56]. Wrist blood pressure monitors with advanced positing sensor (APS) have been validated against mercury sphygmomanometers according to the International Protocol of the European Society of Hypertension [57, 58].

In our feasibility test, firefighters successfully assessed their blood pressure with the Omron wrist blood pressure monitor every hour during the daytime at the fire station on consecutive 24-hr shifts. Saliva cortisol has been widely used for decades due to its simple and non-invasive characteristics [59]. Saliva CRP has not been used widely because of the lack of information about the relationship between saliva CRP and serum CRP. However, recent papers reported that there is a high correlation between serum and saliva CRP levels [60] and a significant difference in salivary cortisol between healthy and cardiac patients [61] and between non-smokers and smokers [62]. Saliva CRP is a promising non-invasive CVD biomarker that can be easily collected and analyzed along with salivary cortisol, although its relationship with work demands has not been explored in firefighters and other occupations. Our pilot study supported the feasibility of the assessment of several cardiovascular strain biomarkers and self-rated stress and fatigue while firefighters were doing a very long shift.

Developing a theoretical framework for studying cardiovascular strain in firefighters on very long shifts

Researchers [63–65] have proposed several mechanisms whereby shift-work could affect CVD. These include the possibility that shift work may increase the risk of CVD by 1) disturbance of circadian rhythms of physiological parameters that are related to the cardiovascular system, 2) stress responses from the exposure to adverse psychosocial working conditions (e.g., job strain or effort-reward imbalance) including disrupting normal social relations (e.g., with family), and/or 3) changes in health behaviors (e.g., sleep quality, eating behaviors, and physical activities). In addition, long working hours (overtime) can aggravate the aforementioned effects of shift work and may significantly increase the risk of CVD when combined with decreased recovery, particularly insufficient sleep [27, 66]. Although the proposed mechanisms are a good general guide for research on long-term effects of shift work and long work hours and CVD, they need to be further elucidated and specified for research in firefighters.

We developed a theoretical framework for studying cardiovascular strain in firefighters on consecutive 24-hr shifts. The developed theoretical framework was built on an extensive literature review, our recently completed studies with firefighters in Southern California, e-mail and discussions with several firefighters on their experiences of consecutive shifts, and our recently conducted feasibility study of several ambulatory cardiovascular strain biomarkers in a small group of firefighters. We suppose that a firefighter has his/her own capacity (“the maximum capacity of a person”) [67] to perform given tasks while maintaining internal psychological and physiological homeostasis [68, 69] (hereafter called, “control capacity” in Figure 1). It is consistent with contemporary ergonomic and systems biology models, for example, the resource model [70] in which workload is defined as the proportion of the maximum capacity used to do given tasks and also with the stress-disequilibrium theory [71] built on an application of systems theory [72] into biology, in which physiological ordering capacity was defined as “a limit on the ability of the organism to internally organize its adaptive interactions with its environments”.

Based on the “heuristic” concept, we hypothesize that the control capacity of the cardiovascular system in firefighters will decrease to some extent through a single 24-hour shift, but it will return to its initial level of capacity following 24-hr off-duty days. However, if a firefighter does 24-hr shifts consecutively, particularly 72 or 96 hours of consecutive work, the control capacity of the cardiovascular system in the firefighter will decrease significantly due to increased work and rest imbalance, which results in accumulating cardiovascular strain over consecutive 24-hr shifts (see Figure 1). Particularly, several interrelated physiological systems or processes such as the autonomic nervous system, hypothalamus pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis, baroreceptor reflex dysfunction, and inflammation processes, all of which are involved in the control of the cardiovascular system will be disturbed at the end of the consecutive shifts. The over-activation of the sympathetic nervous system will result in increased heart rate and blood pressure. The autonomic imbalance will lead to a decrease in heart rate (beat-to-beat R-R interval) variability. Over-activation of the HPA axis will increase salivary cortisol level, particularly in the early morning (usually salivary cortisol increases rapidly after awakening and has its highest value about 30 minutes just after awakening). Increased systematic inflammation may result in an increase and/or a flattened diurnal pattern of salivary CRP. CRP has the highest value just after awakening and the lowest value at midday [73]. If cardiovascular strain accumulates over years through repeated multiple consecutive 24-hr shifts (particularly 72 or 96 hours of consecutive work), it will lead to the “irreversible” loss in control capacity of the cardiovascular system in firefighters (marked as a red real line of the circle in Figure 1 vs. reversible loss marked as a dotted line).

We think that consecutive 24-hr shifts are likely to contribute to psychological strain (e.g., fatigue and distress), sleep disturbance, unhealthy behaviors, and decreased performance at work among firefighters in line with existing literature on long work hours and shift work [25, 74, 75]. It is well-known that physiological parameters (e.g. heart rate, blood pressure, cortisol, and CRP) are influenced by psychological strain, sleep, and health behaviors and that vice versa is true [67, 76–78]. For instance, one experimental study [77] in 10 healthy young adults reported that when they did not have any sleep for 3 days their systolic and diastolic blood pressure and pulse rate dramatically increased from Day 1 to Day 3. High cortisol reactors to a given stressor consumed more calories compared to low cortisol reactors [79]. Nonetheless, one issue regarding blood pressure needs to be discussed for clarity. Some studies have reported that exhaustion [21] and fatigue [80] are negatively associated with blood pressure (that is, the fatigued have lower blood pressure compared to the non-fatigued). However, we think, as Stewart and Write et al. [81] pointed out, that the effect of exhaustion or fatigue on blood pressure at least partly depends on whether the fatigued are willing to or are forced to make more effort given their fatigued status. We think that firefighters cannot and do not give up their social role as first emergency respondents even when they are fatigued. So we anticipate that fatigued firefighters will show higher blood pressure rather than lower blood pressure compared to non-fatigued firefighters.

We think that the cardiovascular strain that results from working very long shifts will differ by several working conditions and individual characteristics. We hypothesize that cardiovascular strain from very long shifts will be higher among firefighters at a busy fire station since they will have less recovery time during the day or at night due to a higher volume of calls. However, we do not exclude the possibility that firefighters at slow stations could also be internally strained for a long period of time because they have to be ready for any unpredictable calls. We think that other adverse psychosocial working conditions (e.g., job strain, effort-reward imbalance, poor social relationships at work, work and family conflict, and frequent consecutive shifts per month) will also increase cardiovascular strain directly through stress [82–84] or indirectly through changes in health behaviors [85].

Firefighters who already have traditional CVD risk factors (e.g., obesity, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia) may experience higher cardiovascular strain during consecutive 24-hr shifts, compared to healthy firefighters without CVD risk factors. It has been reported that increased resting heart rate is associated with obesity [86, 87] and high triglyceride and cholesterol [88] and low heart rate variability is associated with obesity [89], hypertension [90], and hyperlipidemia [91]. However, there is little information on any differential reactivity to a given workload by health status. One study [92] among air-traffic controllers reported that a higher cardiovascular reactivity to workload (defined as the number of planes on the air traffic control screen) was a significant predictor of hypertension 20 years later. This implies that cardiovascular reactivity to a given task may be higher in hypertensive workers. However, this was not the case in one Japanese study [93] in which the blood pressure reactivity to a long work schedule (60 hrs per week) among mild-hypertensive workers was slightly less (1 mm Hg) than among normotensive workers. But in the same study [93], there was a higher reactivity of 24-hr heart rate to the long work schedule among hypertensive workers (5 beats per min vs. 3 beats per min).

A recent experimental animal study [94] reported that obese rats showed a higher cardiovascular reactivity (of heart rate and blood pressure) to the stress of immobilization than non-obese rats. We think (based on e-mail discussions with firefighters in Southern California) that some firefighters try to reduce stress from consecutive 24-hr shifts by increasing healthy behaviors (e.g., exercising at work, eating healthy foods, and having nap times during the day). Thus there is a possibility that firefighters and fire departments can reduce cardiovascular strain in firefighters on consecutive 24-hr shifts by promoting the healthy behaviors of individual firefighters and improving fire department-level safety and health climates which encourage healthy behaviors.

Finally, it is possible that the impact of consecutive shifts on the cardiovascular system of firefighters will differ by the motivation of firefighters (financial needs) and the context of the consecutive shifts (whether they choose the consecutive shifts or are forced to work them; “mandatory vs. voluntary” overtime). On the other hand, the high financial rewards received for working additional shifts may result in decreased cardiovascular strain.

Conclusions

Despite the fact that very long (> 48 hrs) shifts are common among firefighters in the United States, little is known about the impact of consecutive 24-hr shifts on the cardiovascular health of firefighters. As the first step toward our long-term goal of elucidating the role of very long shifts in the development of CVD in firefighters, we developed and described a theoretical framework for studying cardiovascular strain in firefighters on very long shifts (i.e., 3 or 4 consecutive 24-hr shifts) based on an extensive literature review and several recent studies with firefighters in Southern California. We think the theoretical framework developed in this article will facilitate future field studies on consecutive 24-hr shifts and cardiovascular health in firefighters and increase our understanding of the mechanisms by which shift work or long work hours can affect CVD, particularly through CVD biological risk factors.

To the best of our knowledge, few studies have been conducted to examine the associations between very long work shifts and CVD or CVD biological risk factors [25], although some studies have examined the risks of very long shifts for injury and fatigue [95]. Also several researchers [74, 75] have recently emphasized the importance of understanding the mechanisms in order to interpret the epidemiological studies on shift work and CVD correctly. A well-designed field study based on the theoretical framework and a within-subject study design in firefighters is urgently needed in the near future. The future study will meet the public safety sub-sector strategic goal 1.5 (particularly, 1.5.3: “investigate biological mechanisms between psychosocial and physical stressors and subclinical markers of cardiovascular disease”) of the National Occupational Research Agenda (NORA) at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

Lastly, we think the theoretical framework developed in this study could ultimately contribute to establishing a nationwide guideline about sustainable 24-hr work and rest schedules for firefighters with which a firefighter can work without a significant burden on his/her cardiovascular system.

Consent (adult)

A written informed consent was obtained from each of the firefighters who participated in the aforementioned studies.

References

US Fire Administration: Retention and Recruitment for the Volunteer Emergency Services: Challenges and Solutions. http://www.nvfc.org/files/documents/2007_retention_and_recruitment_guide.pdf

Kales SN, Soteriades ES, Christophi CA, Christiani DC: Emergency duties and deaths from heart disease among firefighters in the United States. New Engl J Med 2007, 356: 1207–1215. 10.1056/NEJMoa060357

Geibe JR, Holder J, Peeples L, Kinney AM, Burress JW, Kales SN: Predictors of on-duty coronary events in male firefighters in the United States. Am J Cardiol 2008, 101(5):585–589. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.10.017

Choi B, Schnall P, Dobson M, Israel L, Landsbergis P, Galassetti P, Pontello A, Kojaku S, Baker D: Exploring occupational and behavioral risk factors for obesity in firefighters: a theoretical framework and study design. Saf Health Work 2011, 2: 301–312. 10.5491/SHAW.2011.2.4.301

Kales SN, Tsismenakis AJ, Zhang C, Soteriades ES: Blood pressure in firefighters, police officers, and other emergency responders. Am J Hypertens 2009, 22(1):11–20. 10.1038/ajh.2008.296

Soteriades ES, Smith DL, Tsismenakis AJ, Baur DM, Kales SN: Cardiovascular disease in US firefighters: a systematic review. Cardiol Rev 2011, 19(4):202–215. 10.1097/CRD.0b013e318215c105

Zwirn SA: Examining the consecutive 72 work hour limit. http://www.usfa.fema.gov/pdf/efop/ora_07sz.pdf

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health: Preventing Fire Fighter Fatalities Due to Heart Attacks and Other Sudden Cardiovascular Events. Cincinnati (OH): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication Number; 2007:133.

Martin B: Staffing choices. Fire Chief Magazine Retrieved on January 30, 2012. http://firechief.com/leadership/managementadministration/staffing_choices_0301

Dobson M, Choi B, Schnall P, Wigger E, Garcia J, Israel L, Baker D: Exploring occupational and health behavioral causes of firefighter obesity: a qualitative study. Am J Ind Med 2013, 56(7):776–790. 10.1002/ajim.22151

Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration: Effects of Sleep Schedules on Commercial Motor Vehicle Driver Performance—Part 1. http://www.fmcsa.dot.gov/documents/tb14d.pdf

Barger LK, Ayas NT, Cade BE, Cronin JW, Rosner B, Speizer FE, Czeisler CA: Impact of extended duration shifts on medical errors, adverse events, and attentional failures. PLoS Med 2006, 3(12):e487. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030487

Byczek L, Walton SM, Conrad KM, Reichelt PA, Samo DG: Cardiovascular risks in firefighters: implications for occupational health nurse practice. AAOHN J 2004, 52(2):66–76.

Choi BC: A technique to re-assess epidemiologic evidence in light of the healthy worker effect: the case of firefighting and heart disease. J Occup Environ Med 2000, 42(10):1021–1034. 10.1097/00043764-200010000-00009

Guidotti TL: Occupational mortality among firefighters: assessing the association. J Occup Environ Med 1995, 37(12):1348–1356. 10.1097/00043764-199512000-00004

Clark J: The management effects of firefighters working a consecutive 48-hour shift. http://www.usfa.fema.gov/pdf/efop/efo33641.pdf

Saijo Y, Ueno T, Hashimoto Y: Twenty-four-hour shift work, depressive symptoms, and job dissatisfaction among Japanese firefighters. Am J Ind Med 2008, 51(5):380–391. 10.1002/ajim.20571

Choi B, Dobson M, Schnall P, Israel L, Baker D: Frequent consecutive 24-hr shift work and exhaustion in firefighters [abstract]. Washington, DC: Presented at the The 2011 American Public Health Association Conference, October 29 to November 2, 2011;

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP, Schaufeli WB, Schwab RL: Maslach Burnout Inventory 3rd Edition Manual. Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996.

Lett HS, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Sherwood A, Strauman T, Robins C, Newman MF: Depression as a risk factor for coronary artery disease: evidence, mechanisms, and treatment. Psychosom Med 2004, 66(3):305–315. 10.1097/01.psy.0000126207.43307.c0

Melamed S, Shirom A, Toker S, Berliner S, Shapira I: Burnout and risk of cardiovascular disease: evidence, possible causal paths, and promising research directions. Psychol Bull 2006, 132(3):327–353.

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) After working three consecutive 24-hour shifts and fighting an extensive structure, a 47-year old career LT suffers sudden cardiac death during physical fitness training – California (Fire fighter fatality investigation report F2007–22). http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face200722.html

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Deputy fire chief suffers sudden cardiac arrest about one hour after conducting a fire prevention inspection – California (Fire fighter fatality investigation report F2008–31). http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/reports/face200831.html

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Fire fighter suffers heart attack while fighting grass fire and dies 2 days later – California (Fire fighter fatality investigation report F2011–01). http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/fire/pdfs/face201101.pdf

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH): Overtime and Extended Work Shifts: Recent Findings on Illnesses, Injuries and Health Behaviors. Cincinnati (OH): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication Number; 2004:143.

Barger L, Cade B, Ayas , Cronin J, Rosner B, Speizer F, Czeisler C: Harvard Work Hours, Health, and Safety Group: Extended work shifts and the risk of motor vehicle crashes among interns. N Engl J Med 2005, 352: 125–134. 10.1056/NEJMoa041401

van der Hulst M: Long workhours and health. Scand J Work Environ Health 2003, 29(3):171–188. 10.5271/sjweh.720

McEwen BS, Seeman T: Protective and damaging effects of mediators of stress: elaborating and testing the concepts of allostasis and allostatic load. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999, 896: 30–47. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08103.x

Meshkati N, Hancock P, Rahimi M, Dawes SM: Techniques in mental workload assessment. In Evaluation of Human Work: A Practical Ergonomics Methodology. 2nd edition. Edited by: Wilson JR, Corlett EN. Philadelpia (PA): Taylor & Francis; 1995:749–782.

Kilbom A: Measurement and assessment of dynamic work. In Evaluation of Human Work: A Practical Ergonomics Methodology. 2nd edition. Edited by: Wilson JR, Corlett EN. Philadelpia (PA): Taylor & Francis; 1995:640–661.

Nachreiner F: International standards on mental work-load–the ISO 10,075 series. Ind Health 1999, 37(2):125–133. 10.2486/indhealth.37.125

Kapit W, Macey RI, Meisami E: The Physiology Coloring Book. 2nd edition. San Francisco (CA): BenjaminCummings; 1999.

Yasmin , McEniery CM, Wallace S, Mackenzie IS, Cockcroft JR, Wilkinson IB: C-reactive protein is associated with arterial stiffness in apparently healthy individuals. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2004, 24(5):969–974. 10.1161/01.ATV.zhq0504.0173

Dyer AR, Persky V, Stamler J, Paul O, Shekelle RB, Berkson DM, Lepper M, Schoenberger JA, Lindberg HA: Heart rate as a prognostic factor for coronary heart disease and mortality: findings in three Chicago epidemiologic studies. Am J Epidemiol 1980, 112(6):736–749.

Gillman MW, Kannel WB, Belanger A, D’Agostino RB: Influence of heart rate on mortality among persons with hypertension: the Framingham Study. Am Heart J 1993, 125(4):1148–1154. 10.1016/0002-8703(93)90128-V

Kannel WB, Kannel C, Paffenbarger RS Jr, Cupples LA: Heart rate and cardiovascular mortality: the Framingham Study. Am Heart J 1987, 113(6):1489–1194. 10.1016/0002-8703(87)90666-1

Palatini P, Benetos A, Grassi G, Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, Mancia G, Narkiewicz K, Parati G, Pessina AC, Ruilope LM, Zanchetti A: European society of hypertension: identification and management of the hypertensive patient with elevated heart rate: statement of a european society of hypertension consensus meeting. J Hypertens 2006, 24(4):603–610. 10.1097/01.hjh.0000217838.49842.1e

Cooney MT, Vartiainen E, Laatikainen T, Juolevi A, Dudina A, Graham IM: Elevated resting heart rate is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease in healthy men and women. Am Heart J 2010, 159(4):612–619.e3. 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.12.029

Huikuri HV, Niemelä MJ, Ojala S, Rantala A, Ikäheimo MJ, Airaksinen KE: Circadian rhythms of frequency domain measures of heart rate variability in healthy subjects and patients with coronary artery disease: effects of arousal and upright posture. Circulation 1994, 90(1):121–126. 10.1161/01.CIR.90.1.121

Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology: Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Circulation 1996, 93(5):1043–1065. 10.1161/01.CIR.93.5.1043

Staessen JA, Beilin L, Parati G, Waeber B, White W: Task force IV: Clinical use of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Participants of the 1999 Consensus Conference on Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring. Blood Press Monit 1999, 4(6):319–331.

Mancia G, Zanchetti A, Agabiti-Rosei E, Benemio G, de Cesaris R, Fogari R, Pessina A, Porcellati C, Rappelli A, Salvetti A, Trimarco B: Ambulatory blood pressure is superior to clinic blood pressure in predicting treatment-induced regression of left ventricular hypertrophy. SAMPLE Study Group. Study on Ambulatory Monitoring of Blood Pressure and Lisinopril Evaluation. Circulation 1997, 95(6):1464–1470. 10.1161/01.CIR.95.6.1464

Fagard RH, Staessen JA, Thijs L: Relationships between changes in left ventricular mass and in clinic and ambulatory blood pressure in response to antihypertensive therapy. J Hypertens 1997, 15(12):1493–1502. 10.1097/00004872-199715120-00018

Glynn RJ, Field TS, Rosner B, Hebert PR, Taylor JO, Hennekens CH: Evidence for a positive linear relation between blood pressure and mortality in elderly people. Lancet 1995, 345(8953):825–829. 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)92964-9

Barnard RJ, Duncan HW: Heart rate and ECG responses of fire fighters. J Occup Med 1975, 17(4):247–250.

Kuorinka I, Korhonen O: Firefighters’ reaction to alarm, an ECG and heart rate study. J Occup Med 1981, 23(11):762–766. 10.1097/00043764-198111000-00010

Sothmann MS, Saupe K, Jasenof D, Blaney J: Heart rate response of firefighters to actual emergencies. Implications for cardiorespiratory fitness. J Occup Med 1992, 34(8):797–800. 10.1097/00043764-199208000-00014

Takeyama H, Itani T, Tachi N, Sakamura O, Murata K, Inoue T, Takanishi T, Suzumura H, Niwa S: Effects of shift schedules on fatigue and physiological functions among firefighters during night duty. Ergonomics 2005, 48(1):1–11. 10.1080/00140130412331303920

Saha PN, Datta SR, Banerjee PK, Narayane GG: An acceptable workload for Indian workers. Ergonomics 1979, 22(9):1059–1071. 10.1080/00140137908924680

Ilmarinen J: Physical load on the cardiovascular system in different work tasks. Scand J Work Environ Health 1984, 10(Suppl 6):403–408.

Wu HC, Wang MJ: Relationship between maximum acceptable work time and physical workload. Ergonomics 2002, 45(4):280–289. 10.1080/00140130210123499

Dekker MJ, Koper JW, van Aken MO, Pols HA, Hofman A, de Jong FH, Kirschbaum C, Witteman JC, Lamberts SW, Tiemeier H: Salivary cortisol is related to atherosclerosis of carotid arteries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008, 93(10):3741–3747. 10.1210/jc.2008-0496

Hurwitz Eller N, Netterstrøm B, Hansen AM: Cortisol in urine and saliva: relations to the intima media thickness, IMT. Atherosclerosis 2001, 159(1):175–185. 10.1016/S0021-9150(01)00487-7

Ridker PM: High-sensitivity C-reactive protein, inflammation, and cardiovascular risk: from concept to clinical practice to clinical benefit. Am Heart J 2004, 148(Suppl 1):S19-S26.

Gamelin FX, Berthoin S, Bosquet L: Validity of the polar S810 heart rate monitor to measure R-R intervals at rest. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2006, 38(5):887–893. 10.1249/01.mss.0000218135.79476.9c

Nunan D, Donovan G, Jakovljevic DG, Hodges LD, Sandercock GR, Brodie DA: Validity and reliability of short-term heart-rate variability from the Polar S810. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009, 41(1):243–250. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318184a4b1

Asmar R, Khabouth J, Topouchian J, el Feghali R, Mattar J: Validation of three automatic devices for self measurement of blood pressure according to the International Protocol: The Omron M3 Intellisense (HEM-7051-E), the Omron M2 Compact (HEM 7102-E), and the Omron R3-I Plus (HEM 6022-E). Blood Press Monit 2010, 15(1):49–54. 10.1097/MBP.0b013e3283354b11

Omboni S, Riva I, Giglio A, Caldara G, Groppelli A, Parati G: Validation of the Omron M5-I, R5-I and HEM-907 automated blood pressure monitors in elderly individuals according to the international protocol of the European society of hypertension. Blood Press Monit 2007, 12(4):233–242. 10.1097/MBP.0b013e32813fa386

Chida Y, Steptoe A: Cortisol awakening response and psychosocial factors: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Biol Psychol 2009, 80(3):265–278. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2008.10.004

Ouellet-Morin I, Danese A, Williams B, Arseneault L: Validation of a high-sensitivity assay for C-reactive protein in human saliva. Brain Behav Immun 2011, 25(4):640–646. 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.12.020

Punyadeera C, Dimeski G, Kostner K, Beyerlein P, Cooper-White J: One-step homogeneous C-reactive protein assay for saliva. J Immunol Methods 2011, 373(1–2):19–25.

Azar R, Richard A: Elevated salivary C-reactive protein levels are associated with active and passive smoking in healthy youth: a pilot study. J Inflamm 2011, 8(1):37. 10.1186/1476-9255-8-37

Steenland K: Shift work, long hours, and cardiovascular disease: a review. Occ Med 2000, 15: 7–17.

Meijman TF, Mulder G: Psychological aspects of workload. In Handbook of Work and Organizational Psychology. Edited by: Drenth PJ, Thierry H, de Wolff CJ. Hove (UK): Psychology Press; 1998:5–33.

Smith CS, Robie C, Folkard S, Barton J, Macdonald I, Smith L, Spelten E, Totterdell P, Costa G: A process model of shiftwork and health. J Occup Health Psychol 1999, 4(3):207–218.

Härmä M: Workhours in relation to work stress, recovery and health. Scand J Work Environ Health 2006, 32(6):502–514. 10.5271/sjweh.1055

Roger SH: Heart rate interpretation methodology. In Ergonomic Design for People at Work, Volume 2. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold; 1986:174–191.

Cannon WB: Organization for physiological homeostasis. Physiol Rev 1929, 9: 399–431.

Day TA: Defining stress as a prelude to mapping its neurocircuitry: no help from allostasis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2005, 29(8):1195–1200. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.08.005

Kroemer KE, Kroemer H, Kroemer-Elbert K: Ergonomics: How to Design for the Ease & Efficiency. Englewood Cliffs (NJ): Prentice Hall; 1994.

Karasek R: Low social control and physiological deregulation—the stress–disequilibrium theory, towards a new demand–control model. Scand J Work Environ Health 2008, (Suppl 6):117–135.

von Bertalanffy L Revised edition. In General Systems Theory. New York: George Braziller; 1968.

Koc M, Karaarslan O, Abali G, Batur MK: Variation in high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels over 24 hours in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Tex Heart Inst J 2010, 37(1):42–48.

Frost P, Kolstad HA, Bonde JP: Shift work and the risk of ischemic heart disease - a systematic review of the epidemiologic evidence. Scand J Work Environ Health 2009, 35(3):163–179. 10.5271/sjweh.1319

Puttonen S, Härmä M, Hublin C: Shift work and cardiovascular disease - pathways from circadian stress to morbidity. Scand J Work Environ Health 2010, 36(2):96–108. 10.5271/sjweh.2894

Howren MB, Lamkin DM, Suls J: Associations of depression with C-reactive protein, IL-1, and IL-6: a metaanalysis. Psychosom Med 2009, 71(2):171–186. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181907c1b

Meier-Ewert HK, Ridker PM, Rifai N, Regan MM, Price NJ, Dinges DF, Mullington JM: Effect of sleep loss on C-reactive protein, an inflammatory marker of cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004, 43(4):678–683. 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.050

Young FL, Leicht AS: Short-term stability of resting heart rate variability: influence of position and gender. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2011, 36(2):210–218. 10.1139/h10-103

Epel E, Lapidus R, McEwen B, Brownell K: Stress may add bite to appetite in women: a laboratory study of stress-induced cortisol and eating behavior. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2001, 26(1):37–49. 10.1016/S0306-4530(00)00035-4

Shapiro D, Jamner LD, Goldstein IB, Delfino RJ: Striking a chord: moods, blood pressure, and heart rate in everyday life. Psychophysiology 2001, 38(2):197–204. 10.1111/1469-8986.3820197

Stewart CC, Wright RA, Hui SK, Simmons A: Outcome expectancy as a moderator of mental fatigue influence on cardiovascular response. Psychophysiology 2009, 46(6):1141–1149. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00862.x

Canivet C, Ostergren PO, Lindeberg SI, Choi B, Karasek R, Moghaddassi M, Isacsson SO: Conflict between the work and family domains and exhaustion among vocationally active men and women. Soc Sci Med 2010, 70(8):1237–1245. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.029

Choi B, Östergren PO, Canivet C, Moghadassi M, Lindeberg S, Karasek R, Isacsson SO: Synergistic interaction effect between job control and social support at work on general psychological distress. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2011, 84(1):77–89. 10.1007/s00420-010-0554-y

Lindeberg SI, Rosvall M, Choi B, Canivet C, Isacsson SO, Karasek R, Ostergren PO: Psychosocial working conditions and exhaustion in a working population sample of Swedish middle-aged men and women. Eur J Public Health 2011, 21(2):190–196. 10.1093/eurpub/ckq039

Choi B, Schnall PL, Yang H, Dobson M, Landsbergis P, Israel L, Karasek R, Baker D: Psychosocial working conditions and active leisure-time physical activity in middle-aged us workers. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 2010, 23(3):239–253.

Ayer JG, Harmer JA, Steinbeck K, Celermajer DS: Postprandial vascular reactivity in obese and normal weight young adults. Obesity 2010, 18(5):945–951. 10.1038/oby.2009.331

Bemelmans RH, van der Graaf Y, Nathoe HM, Wassink AM, Vernooij JW, Spiering W, Visseren FL: Increased visceral adipose tissue is associated with increased resting heart rate in patients with manifest vascular disease. Obesity 2012, 20(4):834–841. 10.1038/oby.2011.321

Freitas Junior IF, Monteiro PA, Silveira LS, Cayres SU, Antunes BM, Bastos KN, Codogno JS, Sabino JP, Fernandes RA: Resting heart rate as predictor of metabolic dysfunctions in obese children and adolescents. BMC Pediatr 2012, 12: 5. doi: :10.1186/1471–2431–12–5 10.1186/1471-2431-12-5

Karason K, Mølgaard H, Wikstrand J, Sjöström L: Heart rate variability in obesity and the effect of weight loss. Am J Cardiol 1999, 83(8):1242–1247. 10.1016/S0002-9149(99)00066-1

Singh JP, Larson MG, Tsuji H, Evans JC, O’Donnell CJ, Levy D: Reduced heart rate variability and new onset hypertension: insights into pathogenesis of hypertension: the Framingham Heart Study. Hypertension 1998, 32(2):293–297. 10.1161/01.HYP.32.2.293

Doncheva NI, Nikolova RI, Danev SG: Overweight, dyslipoproteinemia, and heart rate variability measures. Folia Med 2003, 45(1):8–12.

Ming EE, Adler GK, Kessler RC, Fogg LF, Matthews KA, Herd JA, Rose RM: Cardiovascular reactivity to work stress predicts subsequent onset of hypertension: the Air Traffic Controller Health Change Study. Psychosom Med 2004, 66(4):459–465. 10.1097/01.psy.0000132872.71870.6d

Hayashi T, Kobayashi Y, Yamaoka K, Yano E: Effect of overtime work on 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure. J Occup Environ Med 1996, 38(10):1007–1011. 10.1097/00043764-199610000-00010

Rudyk O, Makra P, Jansen E, Shattock MJ, Poston L, Taylor PD: Increased cardiovascular reactivity to acute stress and salt-loading in adult male offspring of fat fed non-obese rats. PLoS One 2011, 6(10):e25250. 10.1371/journal.pone.0025250

Barger LK, Lockley SW, Rajaratnam SM, Landrigan CP: Neurobehavioral, health, and safety consequences associated with shift work in safety-sensitive professions. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2009, 9(2):155–164. 10.1007/s11910-009-0024-7

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health through grant UL1TR000153. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This study was also supported by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)/NIOSH (Grant #, 5R21OH009911-02), the Center for Social Epidemiology (Marina Del Rey, CA), and the UCI-Institute for Clinical and Translational Science (ICTS). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC/NIOSH. We express our sincere thanks to a fire department and a local union of the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) in Southern California for their support and input for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

All authors have no competing interests to declare.

Authors’ contributions

BC conceived and designed this study. PS, MD, HK, LI, and DB contributed to the design and the literature review of this study. JG contributed to the data collection at fire stations. FZ contributed to the data analysis of saliva samples from firefighters at fire stations. BC drafted this manuscript. All authors (particularly PS, MD, and DB) revised this manuscript critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, B., Schnall, P.L., Dobson, M. et al. Very Long (> 48 hours) Shifts and Cardiovascular Strain in Firefighters: a Theoretical Framework. Ann of Occup and Environ Med 26, 5 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/2052-4374-26-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2052-4374-26-5