Abstract

Background

The background of this study is to determine whether the addition of intravenous colloid to diuretic therapy, in comparison to diuretic therapy alone, improves diuresis and oxygenation and prevents intravascular volume depletion in intensive care unit (ICU) patients without shock.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials, Google Scholar, conference abstracts of ACCP, SCCM, ATS, and references of relevant articles. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of adult ICU patients, not in shock (defined as patients on low dose or no vasopressors, without need for IV fluid bolus or blood transfusion within 24 h), comparing intravenous colloid therapy (human albumin, plasma, synthetic starches, or gels) plus diuretic to control (diuretic alone, or diuretic plus placebo). Two reviewers independently applied eligibility criteria, assessed quality, and extracted data.

Results

Seven hundred fifty five studies were found in the initial search; 14 were deemed relevant; 2 were found to be eligible. There was good agreement between reviewers for study relevance (k = 0.869) and eligibility (k = 0.811). One study of heart failure patients showed no evidence of improved mean or hourly urine output in the group receiving albumin. The second studied patients hypoproteinemic with ARDS and demonstrated an improved fluid balance in 3 days, improved oxygenation status, and improved serum albumin level in patients treated with albumin. No significant differences were found for other outcomes. No studies evaluating colloids other than albumin were found.

Conclusions

Our review is limited by the small number of high-quality RCTs available to study this clinical question, both of which only studied albumin. High-quality RCTs are required to evaluate the effect of albumin as well as other colloids as an adjunct to diuresis in a general ICU population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Many critically ill patients require volume resuscitation with crystalloids, colloids, or blood products to treat the underlying condition which necessitated intensive care unit (ICU) admission. This aggressive resuscitation can lead to volume overload with marked peripheral edema and pulmonary edema and has been associated with the development of the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), as well as higher mortality compared to patients without evidence of volume overload[1, 2]. Observational data from a large European database suggests that positive fluid balance is among the most important prognostic variables for ICU mortality[3], and a retrospective review of the use of intravenous (IV) fluids during the first 4 days of sepsis care in the VASST study showed that a more positive fluid balance at both 12 h and day 4 correlated significantly with mortality[1]. Extending to the ARDS population, it is known that positive fluid balance in addition to a high tidal volume ventilatory strategy is associated with worse outcomes[2], and randomized controlled trial data from Wheeler et al. has shown a conservative IV fluid strategy to be of benefit with respect to improved lung function and duration of mechanical ventilation strategy in a broad ARDS population[4]. More recent data has suggested that in patients with acute lung injury complicating septic shock, adequate initial fluid resuscitation coupled with conservative late fluid management results in optimal outcomes[5]. Thus, in ICU patients without shock, maintenance of a euvolemic state and diuresis of excess fluid received during initial resuscitation is potentially of benefit, with loop diuretics such as furosemide being the standard therapy.

For such patients, a strategy of hyperoncotic colloid infusion followed by a diuretic infusion, such as furosemide, makes physiologic sense. Hyperoncotic colloid promotes redistribution of fluid from edematous peripheral tissues into the vascular compartment, where it can then be filtered at the glomerulus and excreted. This strategy has face validity for all edematous critically ill patients, but particularly so for those in whom critical illness and malnutrition have lead to hypoproteinemia. Low serum protein levels can result in lower vascular oncotic pressure and a tendency for fluid to shixft into the interstitial compartment[6].

Several colloids have the potential to increase colloid osmotic pressure (COP). Albumin has several potential advantages, as a naturally occurring protein whose levels tend to drop in the critically ill due to the effects of circulating inflammatory mediators[6]. Furthermore, furosemide itself is heavily protein-bound, and in hypoproteinemic patients, this results in an increased volume of distribution and lower concentrations of the diuretic in the loop of Henle[7]. The addition of albumin to furosemide has been shown to improve the volume of diuresis in several patient populations, including patients with renal failure[8–10] and cirrhosis[11]. Data from our institution shows that the administration of 100 mL of 25% albumin results in sustained increase in COP of 2.56 mmHg for up to 6 h[12]. Other colloids, notably synthetic hydroxyethyl starches also have the potential to improve COP. In addition to often being less expensive than albumin, they have been shown to have similar effects on COP in critically ill patients, increasing by 1.8 +/-3.1 mmHg for a duration of roughly 4 h[13]. No data about the effects of gelatins or human plasma upon COP could be found.

Thus, in critically ill patients, there is a rationale for studying the addition of colloids, including albumin, synthetic starches, gelatins, or plasma, to standard diuretic therapy in order to improve physiologic endpoints such as volume of diuresis, fluid balance, oxygenation status, as well as clinical outcomes such as ventilator-free days and mortality. However, observational studies have had mixed results[14–17]. Our goal in this systematic review is therefore to assess the highest quality current evidence in this regard, specifically assessing randomized controlled trials, which are at lower risk of bias compared to observational trials.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

We included trials with the following characteristics:

-

1)

Type of studies: Randomized, controlled parallel group or crossover trials

-

2)

Population: Adult patients in the ICU with the characteristics - not in shock (as defined by patients not on vasopressors, or on only low-dose vasopressors; without need for IV fluid bolus or blood product transfusion >24 h), without cirrhosis or the nephrotic syndrome

-

3)

Intervention: Intravenous colloid therapy (human albumin, synthetic starches) plus diuretic therapy

-

4)

Control: Diuretic alone or diuretic plus placebo

-

5)

Outcomes: Prespecified outcomes included the following:

-

a)

The effect on fluid balance, including urine output and weight loss during the treatment period, and any other measurements of volume status used by study authors; effects on hemodynamics, including the need for fluid replacement or blood product transfusion during or within 48 h of therapy, as well as hypotension, tachycardia, use of vasoactive agents; and effect on patient oxygenation (FiO2, PaO2/FiO2 ratio, oxygenation index).

-

b)

Secondary outcomes: effects of serum protein, albumin, or colloid osmotic pressure as well as any chemistry data (serum urea, creatinine, electrolytes). Ventilator-free days, days in ICU, and ICU and total mortality data, if available were also collected.

Search strategy-identification of studies

We conducted a search of MEDLINE (1946 to February 2013), Embase (1980 to February 2013), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials as well as Google Scholar for all trials published from database inception to February 2013. Search strategies for each database can be found in Additional file1: Appendix 1. Abstracts for meetings of American College of Chest Physicians (2003–2012), Society of Critical Care Medicine, American Thoracic Society (2009–2012), and Critical Care Canada Forum (2009–2012) were also hand-searched in duplication for relevant articles. The references of articles reviewed for eligibility were hand-searched in duplicate for further potentially relevant articles. Studies could be published in journals or in abstract form with no language restrictions. Studies of any methodological quality were considered eligible for review; however, only data from studies of moderate to low risk of bias were considered for pooling in a meta-analysis. No language restrictions were applied.

Obvious duplicates of retrieved studies were discarded. Study investigators, study time periods, population characteristics, and study methodology were closely examined to ensure that multiple reports of the same experimental data were not included. The retrieved studies were screened in duplication by the two reviewers (SO, IM) for relevance. Studies considered to be relevant were then assessed in duplication for eligibility. Provision was made for third-party review in the event of primary reviewer disagreement on the eligibility, but this was not necessary. Reviewers were not blinded as to article authors, journal, or results when screening studies for eligibility. Kappa statistics were calculated ensure inter-rater reliability of study relevance and study eligibility.

Data extraction

Data were collected on standardized forms in duplicate by the reviewers. Lead authors of any studies that were missing essential data were contacted via their contact information given on the study.

Methodologic quality assessment

Overall risk of bias of individual studies was assessed according to the tool used for the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews with regards to random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting[18]. Studies were assessed independently by both reviewers and reported as being at a ‘high’, ‘low’, or ‘uncertain’ risk of bias. Disagreements between reviewers were settled by a third party.

Statistical analysis

Data from eligible studies were entered into Revman Version 5.1, the software program used by the Cochrane Collaboration to perform systematic reviews[19]. We prespecified our statistical analysis for our primary and secondary outcomes. Study heterogeneity was to be assessed for each of the primary and secondary outcomes of interest and reported using I2 calculations, with values greater than 50% indicating substantial heterogeneity. For outcomes not found to have significant heterogeneity, summarized outcomes (standardized mean difference for continuous variables, relative risk for dichotomous variables) and 95% confidence intervals were to be calculated using a random-effects model. Prespecified subgroups for analysis included patients with hypoalbuminemia or hypoproteinemia and patients with ALI/ARDS, liver failure, or congestive heart failure, as they were considered the most likely to benefit from intravenous colloid.

Results

Search results

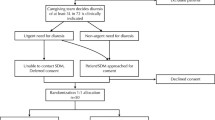

The initial database search resulted in 1,755 articles, which narrowed to 363 once filters limiting results to clinical trials in humans were applied. The Google Scholar search revealed 300 articles, all of which were duplicates or not considered to be relevant for screening. Abstract databases revealed no further relevant publications. Hand searches of the article references revealed two further published abstracts considered to be relevant for screening. Initial screening by the reviewing authors resulted in 14 studies that were considered relevant for eligibility screening. Kappa statistic for agreement between the two authors was 0.869 (95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.742–0.996). After formal eligibility assessment by both reviewers, two studies were considered eligible for the systematic review. The Kappa statistic for agreement was 0.811 (95% CI = 0.460–1.162). There was complete agreement between the reviewers with regard to the overall risk of bias of the studies (Figure 1).

Risk of bias assessment

The two RCTs were found to be at low to moderate risk of bias (Figure 2). Specific ratings of methodological assessment are listed in Table 1. Study authors were contacted to clarify any aspects of the studies that were ambiguous in the published manuscripts; however, further details were not available.

Study results

The larger of the two studies (Martin[20]) randomized 40 patients with ARDS to 25 g of 25% albumin every 8 h or placebo. All patients received an infusion of furosemide (1 mg/mL) titrated to meet a net fluid loss of >1 kg per 24 h with a maximum dose of 8 mg/h[20]. The study by Makhoul et al. randomized 30 mechanically ventilated patients with congestive heart failure to one of three arms: one of intermittent furosemide; one of continuous furosemide infusion, and one of furosemide infusion plus IV albumin infusion. The regimen used was a bolus of 1 mg/kg, followed by an infusion of 0.1 mg/kg/h thereafter. Clinicians could increase the dose every 2 h PRN to keep urine output greater than 1 mL/kg/h. Patients randomized to continuous infusion plus albumin received furosemide at same infusion rate, but the furosemide was mixed into a solution of albumin, 12.5 g albumin per 250 mg of furosemide[21].

Study results are summarized in Table 1. Insufficient data was available in the study data (published or unpublished) to allow for a meta-analysis of any of the pre-specified outcomes. In the Makhoul study, there were no differences in mean total urine output at 24 h, although there was a trend towards a lower dose of furosemide in the group assigned to IV albumin infusion. There were no differences between groups with regard to electrolyte imbalances. In the study by Martin, albumin treatment resulted in increased serum albumin levels and colloid osmotic pressure at 72 h. There was a non-significant trend towards the reduction of the furosemide dose required by the group assigned to albumin (5.2 vs. 7.0 mg/h, p = 0.06). There were improvements in the net fluid balance at day 3 (-5.480 vs. -1.490 L, p < 0.01). There was also an improvement in the oxygenation at 24 h (change in P/F ratio 43 vs. -24, p < 0.01). There were no differences between the groups in cardiac index or mean arterial pressure though there were fewer fluid boluses needed in the group assigned to albumin treatment (11 vs. 35, p value not reported). There were no statistically significant differences between the groups with regard to ventilator-free days or ICU mortality.

Discussion

The strengths of our review are its structured clinical question, thorough systematic search, and independent assessment of study relevance, eligibility, and quality with good agreement between reviewers. Our review is limited by the small number of high-quality RCTs available to study whether the addition of intravenous colloid to diuretic infusion, in comparison to diuretic infusion alone, is of benefit in ICU patients without shock. The two studies that do exist both assessed the effects of albumin, without comparison to other colloids. They were also small and limited to populations with either ARDS or congestive heart failure thus limiting generalizability to a broader critically ill population. Only one of the two high-quality RCTs suggests benefit for the use of albumin in addition to diuretics to improve the physiologic parameters of fluid balance, oxygenation, as well as possibly hemodynamic stability. The significance of this with regard to other patient important outcomes, such as ventilator-free days or mortality, is unknown. Thus, the routine administration of colloids in addition to diuretic cannot be recommended based on the above evidence, although the use of albumin may be considered in hypoproteinemic patients with ARDS who have a poor response to diuresis. Based on the lack of evidence, we are unable to comment on the use of other colloids, such as plasma or starches as an adjunct to diuresis in critically ill patients, although physiologic rationale for them are similar to those of albumin.

For a diuretic strategy that is used frequently, we were surprised at the paucity of high-quality RCT evidence. Further trials are needed to assess whether or not a strategy of albumin combined with furosemide results in improved patient-important outcomes and to determine if the potential benefit of albumin in addition to diuretic can be recommended to a broader population of critically ill patients. Such a trial should have a simple, practical protocol and include a wide range of critically ill patients, as volume overload is common in the ICU. Ideally, such a trial would also be powered to assess patient-important as well as physiologic outcomes.

For hydroxyethyl starches, smaller pilot studies to evaluate their effects upon COP and fluid balance are needed before proceeding to larger clinical trials. Given recent trials demonstrating potential harms of starches for resuscitation in critically ill patients; however, such trials are unlikely to be conducted[22, 23]. Based upon their physiologic effects upon COP, one could theoretically consider their use in patients for whom the use of blood products is unacceptable, though we would not recommend it at the present time.

Finally, for other colloids, such as gelatins or human plasma, no studies investigating their clinical or physiologic effects upon COP or diuresis in critically ill patients could be found. We are thus unable to recommend their use as an adjunct to diuresis in the critically ill population.

Conclusions

Although there is good physiologic rationale for the use of colloids, particularly albumin, in addition to diuretics in critically ill patients with hypoproteinemia, there is a paucity of randomized controlled trials to support this practice. Two small trials comparing albumin to placebo suggest improvement of physiologic parameters, but they do not provide enough data for a meta-analysis. Further trials are needed to assess whether or not a strategy of albumin combined with furosemide results in improved patient-important outcomes and to determine if the potential benefit of albumin in addition to the diuretic can be generalized to a broader population of critically ill patients. No RCTs investigating the effects of starches, gelatins, or plasma as an adjunct to diuresis in the critically ill population exist, and small pilot studies assessing their physiologic effects upon COP and fluid balance are required before any recommendations to their use can be made. Given recent trials demonstrating the potential harms of hydroxethyl starches, such trials are unlikely, though they may still be considered for human plasma and gelatins.

Abbreviations

- ARDS:

-

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- FiO2:

-

fraction of inspired oxygen

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- IV:

-

intravenous

- PaO2/FiO2 or P/F ratio:

-

partial pressure of oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen ratio.

References

Boyd JH, Forbes J, Nakada T-A, Walley KR, Russell JA: Fluid resuscitation in septic shock: a positive fluid balance and elevated central venous pressure are associated with increased mortality. Crit Care Med 2011, 39: 259-265. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181feeb15

Sakr Y, Vincent J-L, Reinhart K, Groeneveld J, Michalopoulos A, Sprung CL, Artigas A, Ranieri VM: High tidal volume and positive fluid balance are associated with worse outcome in acute lung injury. Chest 2005, 128: 3098-3108. 10.1378/chest.128.5.3098

Vincent J-L, Sakr Y, Sprung CL, Ranieri CM, Reinhart K, Gerlach H, Moreno R, Carlet J, Le Gall J-R, Payen D: Sepsis in European intensive care units: results of the SOAP study. Crit Care Med 2006, 34: 344-353. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000194725.48928.3A

Wiedemann HP, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, Thompson BT, Hayden D, deBoisblanc B, Connors AF, Hite RD, Harabin AL, National Heart Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network: Comparison of two fluid-management strategies in acute lung injury. N Engl J Med 2006, 354: 2564-2575.

Murphy CV: The importance of fluid management in acute lung injury secondary to septic shock. Chest 2009, 136: 102. 10.1378/chest.08-2706

Hoste EA, Kellum JA: Acute renal failure in the critically ill: impact on morbidity and mortality. Contrib Nephrol 2004, 144: 1-11.

Wood A, Brater DC: Diuretic therapy. N Eng J Med 1998, 339: 387-395. 10.1056/NEJM199808063390607

Fliser D, Zurbrüggen I, Mutschler E, Bischoff I, Nussberger J, Franek E, Ritz E: Coadministration of albumin and furosemide in patients with the nephrotic syndrome. Kidney Int 1999, 55: 629-634. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00298.x

Dharmaraj R, Hari P, Bagga A: Randomized cross-over trial comparing albumin and frusemide infusions in nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 2009, 24: 775-782. 10.1007/s00467-008-1062-0

Phakdeekitcharoen B, Boonyawat K: The added-up albumin enhances the diuretic effect of furosemide in patients with hypoalbuminemic chronic kidney disease: a randomized controlled study. BMC Nephrol 2012, 13: 92. 10.1186/1471-2369-13-92

Gentilini P, Casini-Raggi V, Fiore GD, Romanelli RG, Buzzelli G, Pinzani M, La Villa G, Laffi G: Albumin improves the response to diuretics in patients with cirrhosis and ascites: results of a randomized, controlled trial. J Hepatol 1999, 30: 639-645. 10.1016/S0168-8278(99)80194-9

Devji TS, Kruisselbrink J, Macri CJ, Wong JMH, Hamielec CM: Effect of intravenous fluid types on colloid osmotic pressure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013, 187: A3949.

Mbaba Mena J, De Backer D, Vincent JL: Effects of a hydroxyethylstarch solution on plasma colloid osmotic pressure in acutely ill patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg 2000,51(1):39-42.

Vinocur B, Artz JS, Sampliner JE: The effects of albumin and diuretics on the alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient in patients with pulmonary insufficiency. Crit Care 1975, 3: 48.

Ferreira da Cunha D, Santana FH, Guiares Tachotti FJ, da Cunha SF C: Intravenous albumin administration and body water balance in critically ill patients. Nutrition 2003, 19: 157-158. 10.1016/S0899-9007(02)01035-3

Cordemans C, De Laet I, Van Regenmortel N, Schoonheydt K, Dits H, Martin G, Huber W, Malbrain MLNG: Aiming for a negative fluid balance in patients with acute lung injury and increased intra-abdominal pressure: a pilot study looking at the effects of PAL-treatment. Ann Intensive Care 2012,2(Suppl 1):S15. 10.1186/2110-5820-2-S1-S15

Doungngern T, Huckleberry Y, Bloom JW, Erstad B: Effect of albumin on diuretic response to furosemide in patients with hypoalbuminemia. Am J Crit Care 2012, 21: 280-286. 10.4037/ajcc2012999

Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savović J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JAC: The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343: d5928. 10.1136/bmj.d5928

Revman Version 5.1. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011.

Martin GS, Moss M, Wheeler AP, Mealer M, Morris JA, Bernard GR: A randomized, controlled trial of furosemide with or without albumin in hypoproteinemic patients with acute lung injury. Crit Carehy Med 2005, 33: 1681-1689. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000171539.47006.02

Makhoul N, Riad T, Friedstrom S, Zveibil FR: Frusemide in pulmonary oedema: continuous versus intermittent. Clin Intensive Care 1997, 8: 273-276. 10.3109/tcic.8.6.273.276

Perner A, Haase N, Guttormsen AB, Tenhunen J, Klemenzson G, Aneman A, Madsen KR, Møller MH, Elkjær JM, Poulsen LM, Bendtsen A, Winding R, Steensen M, Berezowicz P, Søe-Jensen P, Bestle M, Strand K, Wiis J, White JO, Thornberg KJ, Quist L, Nielsen J, Andersen LH, Holst LB, Thormar K, Kjældgaard A-L, Fabritius ML, Mondrup F, Pott FC, Møller TP, et al.: Hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.4 versus Ringer’s acetate in severe sepsis. N Engl J Med 2012, 367: 124-134. 10.1056/NEJMoa1204242

Myburgh JA, Finfer S, Bellomo R, Billot L, Cass A, Gattas D, Glass P, Lipman J, Liu B, McArthur C, McGuinness S, Rajbhandari D, Taylor CB, Webb SAR: Hydroxyethyl starch or saline for fluid resuscitation in intensive care. N Engl J Med 2012, 367: 1901-1911. 10.1056/NEJMoa1209759

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Dr. Cindy Hamielec and Dr. Maureen Meade for their support and feedback during this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SO and IM jointly developed the search strategy, reviewed abstracts and papers, extracted data, and wrote the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Oczkowski, S.J., Mazzetti, I. Colloids to improve diuresis in critically ill patients: a systematic review. j intensive care 2, 37 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/2052-0492-2-37

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2052-0492-2-37