Abstract

To analyse deposition of fine particulate matter (PM) on book surfaces we put twelve bunches of cellulose filters on a free shelf of the National Library in Prague, exposed them for three, six, nine, and twelve months to indoor air and analysed them after each period by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Ion Chromatography (IC). Results showed that fine particles were deposited predominantly on the surface of the top filter but partly also on the surfaces of inner filters. It indicates fine particles penetrated between filters. The penetration and deposition of particles was also modelled as Brownian diffusion between two parallel filters. The model prediction demonstrated that fine particles penetrate between filters, with the depth of penetration limited by parallel diffusional deposition on filter surfaces. This is in qualitative agreement with SEM and IC investigations. The results show that beside the top part fine PM can deposit onto all available surfaces of books.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Airborne particles deposited on cultural heritage artefacts have many negative effects. Beside soiling and abrasion of surfaces particles can also cause material deterioration by chemical reactions. Ultrafine atmospheric particles, penetrating indoors from the outdoor environment, contain soot and organic matter from traffic that are hygroscopic and effective for transport of acids. Fine particles consist of secondary organic matter and ammonium sulfate, ammonium nitrate, and sometimes sulfuric acid. Coarse particles, formed predominantly by resuspended dust contain crustal elements and in the indoor environment sometimes alkaline particles emitted from concrete structures [1, 2].

There are several studies reporting particle deposition measurements in museums and other buildings with works of art or historical artefacts [3–13]. The deposition has been determined using vertical and horizontal collection plates or filters, attached to the walls or horizontal surfaces with subsequent analysis of amount and chemical composition of deposit by various techniques. The results, though somewhat diverse, have several common features: a) the amount of deposit on the horizontal surfaces is larger than on vertical surfaces, b) the composition of deposit corresponds to the composition of particulate matter (PM) suspended in the indoor air, and c) particles deposited on vertical surfaces are formed frequently by soot, organic matter and ammonium sulphate. The rate of submicron particle and sulfate deposition onto a vertical surfaces measured inside five Southern California Museums were in a good agreement with theoretical prediction [14].

Dry deposition is considered to occur by a combination of Brownian and eddy diffusion and gravitational settling [15, 16] where prevailing deposition mechanism depends on the particle size. Coarse particles are deposited on upward-facing surfaces by gravitational settling and fine particles predominantly by diffusion on surfaces of any orientation. In principle the submicron particles can penetrate by diffusion also between books and even into the gaps between pages and thus can be deposited on the inner surfaces of books. To test this hypothesis we examined deposition of particles on paper filters located on the free shelf of the library.

Experimental

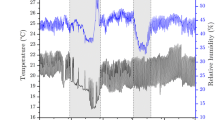

The deposition experiments were performed during one year comprehensive study of indoor air quality in the Baroque Library Hall of the National Library in Prague, that included measurements of gaseous pollutants, size resolved particle number concentrations, and size resolved chemical composition of indoor PM. The results showed that the average concentrations of size fraction 100 nm - 1 μm of the indoor PM was of the order 103 particles/cm3. The IC analyses revealed that the major water-soluble norganic component of this fraction was ammonium sulfate with maximum concentration centred at about 300 nm [17].

To investigate deposition of fine PM we placed twelve bunches of ten cellulose Whatman filters No. 542 (circles, 70 mm), fixed in open Petri dishes, on a free shelf of the library (Figures 1 and 2). Each bunch contained ten filters, which were gently loosed to increase the distance between them. Whatman filters were chosen since due to low blank were suitable a) for subsequent analyses of deposit and b) for study of possible effect of deposited PM on degradation of cellulose, as main component of paper. In the experiment bunches of filters represented books, laying on the shelf.

Bunches were exposed for three, six, nine, and twelve months and examined after each period by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Ion Chromatography (IC).

Particle penetration and deposition

To estimate penetration of particles between filters and subsequent deposition on inner surfaces we modelled transport of particles by Brownian diffusion between two parallel discs (Figure 3) put in environment with constant particle number concentration n 0 .

The particle concentration was described by the equation

where n is the particle number concentration, t is the time, r and z are the radial and axial distances, respectively, and D is the particle diffusion coefficient [18]

where k is the Boltzmann’s constant, T is the temperature, C c is the slip correction factor, η is the air viscosity, and d p is the particle diameter. The slip correction factor C c is given by

where mean free path λ for air at standard conditions is 0.066 μm. The solution of the equation (1) with boundary conditions

gives the concentration gradient ∂n/∂z at filer surfaces z = 0, z = Z and using Fick’s law the rate of particle deposition per unit area of surface

The equation (1) was solved numerically for particle sizes d p = 10, 100, and 1000 nm, gap width Z = 1 and 5 mm, and constant particle number concentration n 0 = 1.103 particles/cm3. An example of steady state concentration profile of 1000 nm particles in 5 mm gap is shown in Figure 4.

As can be seen the concentration of particles rapidly decreases with increasing distance from the edge due to fast deposition by axial diffusion. To estimate the deposition we calculated amount and mass of particles (assuming spherical particles of unit density) deposited on inner surface during one year of exposition. (i.e. J.t). The results showed that particle penetration and deposition depends on particle size and width of the gap, with the depth of the penetration limited by parallel diffusional deposition on filter surfaces. Smaller particles penetrated faster and deeper resulting in higher particle number concentration of deposited particles but higher mass was transported by larger particles.

Scanning electron microscopy

Surfaces of the top (first) and internal (second) filter were analysed by Scanning Electron Microscopy (Quanta 450, FEI, USA). The samples were coated by gold and viewed with the microscope at 20 kV. Typical example of particles deposited on the top filter is shown in Figure 5. At high magnification particles of different appearance and size were distinguished: spherical and irregular particles, larger aggregates of smaller particles, and fibres with sizes between about 50 nm to 50 μm. Some particles were also analyzed by using SEM-EDAX. Large irregular particles contained usually crustal elements Si, Al, and Ca indicating mineral origin. Several smaller spherical particles contained C and O and occasionally showed some instability under the electron beam indicating biological matter. Examination of internal filters showed that the particles were deposited on small area extending about 1 mm from the filter edge, that qualitatively corresponds to the model prediction. However, direct comparison was difficult, since model differs from the real arrangement: filters fixed inside shelf on Petri dishes were not exactly parallel and gaps between filters were not constant (Figure 2), surface and edge of filters had a fibrous character (Figure 5), that differs from the smooth surface assumed in modelling, and indoor aerosol particles were polydisperse with highly time variable concentrations.

Ion chromatography

Results from the parallel study [17] showed that ammonium sulfate formed up to 60% of mass of water-soluble part of indoor submicron PM. Since ammonium sulfate is stable compound, it is considered as a tracer of ambient fine aerosols that penetrate indoors [19, 20]. In this study sulfate was used as a marker for deposited particles.

Exposed filters were analysed after each period by Ion Chromatography (IC). Since the bunches were not exactly planar but slightly convex (see Figure 2) the downward-facing surface of the last filter could be exposed as well. Thus, we analysed the top (first), internal (second) and bottom (tenth) filter from two bunches after each period. The analyses were provided using the setup by Watrex Ltd., Czech Rep., with columns Watrex IC Anion II 10 μm 150 × 3 mm for anions and Alltech universal cation 7 μm 100 × 4.6 mm for cations. The conductivity detector used in this setup was a SHODEX CD-5. The samples were extracted by 10 ml of ultrapure water with conductivity 0.08 μSm− 1 (Ultrapur, Watrex Ltd.) for 0.5 h using ultrasonic bath and 1 h using a shaker. The filtered extracts were then analysed for anions and the next day for cations. The sample solutions for cation analysis were stored in the fridge prior the analysis.

Results of analyses, corrected for the blank value, are shown in Figure 6. As can be seen, sulfate concentrations on all filters increased with time. Substantially higher sulfate concentrations were found on the top filter predominately due to larger exposed area. These results were confirmed by statistical analysis (Wilcoxon test, p < 0.05), which showed significant differences only between the top and other two filters. A non-parametric test was chosen, because the Shapiro-Wilk test rejects the hypothesis of normal distribution for the bottom filter at p < 0.05. The results clearly show, that submicron particles penetrated between filters with transport governed at least to the downward-facing surface (Figure 2) of the bottom filter by diffusion.

Conclusions

To test if the indoor submicron particles can penetrate by diffusion into gaps between books or even between pages of books, we exposed twelve bunches of Whatman filters to the indoor air fixed in open Petri dishes on a free shelf of the library. Bunches were exposed for three, six, nine, and twelve months and analysed after each period by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Ion Chromatography (IC). The penetration and deposition of particles has been modelled assuming Brownian diffusion between two parallel discs, The simple model showed that the particle penetration and deposition depends on particle size and width of the gap, with the depth of penetration limited by parallel diffusional deposition on filter surfaces. Smaller particles penetrate faster and deeper resulting in higher particle number concentration of deposited particles, but higher mass is transported by larger particles. The results of modelling have been qualitatively confirmed by Ion Chromatography using sulfate as marker for deposited particles. The results show that beside the top part fine PM can deposit onto all available surfaces of books.

References

Nazaroff WW, Ligocki MP, Salmon LG, Cass GR, Fall T, Jones MC Liu HIH, Ma T: Airborne particles in museums. J Paul Getty Trust. 1993, Publication of the Getty Conservation Institute, available online: http://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/pdf_publications/pdf/airborne.pdf,

Hatchfield PB: Pollutants in the museum environment. 2005, London: Archetype Publications Ltd

Ligocki MP, Liu HIH, Cass GR: Measurements of particle deposition rates inside southern California museums. Aerosol Sci Technol. 1990, 13: 85-101. 10.1080/02786829008959426.

Nazaroff WW, Salmon LG, Cass GR: Concentration and fate of airborne particles in museums. Environ Sci Technol. 1990, 24: 66-77. 10.1021/es00071a006.

Christoforou CC, Salmon LG, Cass GR: Deposition of atmospheric particles within the Buddhist cave temples at Yungang, China. Atmos Environ. 1994, 28 (12): 2081-2091. 10.1016/1352-2310(94)90475-8.

De Bock LA, Van Grieken RE, Camuffo D, Grime GW: Microanalysis of museum aerosol to elucidate the soiling of paintings: case of the Correr museum, Venice, Italy. Environ Sci Technol. 1996, 30: 3341-3350. 10.1021/es9602004.

Brimblecombe P, Blades N, Camuffo D, Stuarto G, Valentino A, Gysels K, Van Grieken R, Busse H-J, Kim O, Ulrich U, Wieser M: The indoor environmet of a modern museum building, the Sainsbury centre for visual arts, Norwich, UK. Indoor Air. 1999, 9: 146-164. 10.1111/j.1600-0668.1999.t01-1-00002.x.

Camuffo D, Brimblecombe P, Van Grieken R, Busse H-J, Sturaro G, Valentino A, Bernardi A, Blades N, Shooter D, De Bock L, Gysels K, Wieser M, Kim O: Indoor air quality at the Correr museum, Venice, Italy. Sci Tot Environ. 1999, 236: 135-152. 10.1016/S0048-9697(99)00262-4.

Gysels K, Deutsch F, Van Grieken R: Characterisation of particulate matter in the Royal museum of fine arts, Antwerp, Belgium. Atmos Environ. 2002, 36: 4103-4113. 10.1016/S1352-2310(02)00229-7.

Gysels K, Delalieux F, Deutsch F, Van Grieken R, Camuffo D, Bernardi A, Sturaru G, Busse H-J, Wieser M: Indoor environment and conservation in the Royal museum of fine arts, Atwerp, Belgium. J Cult Herit. 2004, 5: 221-230. 10.1016/j.culher.2004.02.002.

Worobiec A, Samek L, Spolnik Z, Kontozova V, Stefaniak E, Van Grieken R: Study of the winter and summer changes of the air composition in the church of Szalowa, Poland, related to conservation. Microchim Acta. 2007, 156: 253-261.

Worobiec A, Samek L, Krata A, Van Meel K, Krupinska B, Stefaniak EA, Karaskiewicz P, Van Grieken R: Transport and deposition of airborne pollutants in exhibition areas located in historical buildings-study in Wavel castle museum in Cracow, Poland. J Cult Herit. 2010, 11: 354-359. 10.1016/j.culher.2009.11.009.

Nava S, Becherini F, Bernardi F, Bonazza A, Chiari M, García-Orellana I, Lucarelli F, Ludwig N, Migliori A, Sabbioni C, Udisti R, Valli G, Vecchi R: An integrated approach to asses air pollution threats to cultural heritage in a semi-confined environment: The case study of Michelozzo’s Courtyard in Florence (Italy). Sci Total Environ. 2009, 408 (6): 1403-1413.

Nazaroff WW, Ligocki MP, Ma T, Cass GR: Particle deposition in museums: comparison of modelling and measurement results. Aerosol Sci Technol. 1990, 12: 332-348.

Lai ACK, Nazaroff WW: Modelling indoor particle deposition from turbulent flow onto smooth surfaces. J Aerosol Sci. 2000, 31 (4): 463-476. 10.1016/S0021-8502(99)00536-4.

Nazaroff WW, Cass GR: Mass-transport aspects of pollutant removal at indoor surfaces. Environ Int. 1989, 16: 567-584.

Andělová L, Smolík J, Ondráčková L, Ondráček J, López-Aparicio S, Grøntoft T, Stankiewicz J: Characterization of airborne particles in the Baroque Hall of the National Library in Prague. e-Preservation Science. 2010, 7: 141-146.

Hinds WC: Aerosol technology, properties, behavior, and measurements of airborne particles. 1999, New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, Chpt. 7 Brownian Motion and Diffusion, 2

Slanina J, ten Brink HM, Otjes RP, Even A, Jongejan P, Khlystov A, Waijers-Ijpelaan A, Hu M, Lu Y: The continuous analysis of nitrate and ammonium in aerosols by the steam jet aerosol collector (SJAC): extension and validation of the methodology. Atmos Environ. 2001, 35: 2319-2330. 10.1016/S1352-2310(00)00556-2.

Pszenny A, Fischer C, Mendez A, Zetwo M: Direct comparison of cellulose and quartz fiber filters for sampling submicrometer aerosols in the marine boundary layer. Atmos Environ. 1993, 27A: 281-284.

Acknowledgement

This work is a part of research project No. DF11P01OVV020 supported by the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JS prepared the manuscript. LM performed analyses. NZ performed mathematical modeling. LO performed PM measurements. JO performed PM measurements. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Smolík, J., Mašková, L., Zíková, N. et al. Deposition of suspended fine particulate matter in a library. herit sci 1, 7 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-7445-1-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-7445-1-7