Abstract

In 2012, an estimated 8.6 million people developed tuberculosis (TB) and 1.3 million died from the disease. With its recent resurgence with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV); TB prevention and management has become further challenging. We systematically evaluated the effectiveness of community based interventions (CBI) for the prevention and treatment of TB and a total of 41 studies were identified for inclusion. Findings suggest that CBI for TB prevention and case detection showed significant increase in TB detection rates (RR: 3.1, 95% CI: 2.92, 3.28) with non-significant impact on TB incidence. CBI for treating patients with active TB showed an overall improvement in treatment success rates (RR: 1.09, 95% CI: 1.07, 1.11) and evidence from a single study suggests significant reduction in relapse rate (RR: 0.26, 95% CI: 0.18, 0.39). The results were consistent for various study design and delivery mechanism. Qualitative synthesis suggests that community based TB treatment delivery through community health workers (CHW) not only improved access and service utilization but also contributed to capacity building and improving the routine TB recording and reporting systems. CBI coupled with the DOTS strategy seem to be an effective approach, however there is a need to evaluate various community-based integrated delivery models for relative effectiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Multilingual abstracts

Please see Additional file 1 for translations of the abstract into the six official working languages of the United Nations.

Introduction

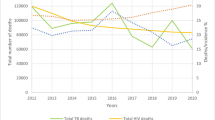

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a major global health problem. In 2012, an estimated 8.6 million people developed TB and 1.3 million died from the disease [1]. The number of TB deaths is unacceptably large given that most of these deaths are preventable. With the recent resurgence related to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), TB prevention and management has become further challenging [2–4]. TB is preventable as well as curable and its transmission could be prevented by prompt identification and treatment of the infected person. However; ensuring treatment completion is crucial for the prevention of relapse and secondary drug resistance. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends Stop TB Strategy based on the Directly Observed Therapy, Short-course (DOTS) to control TB. The strategy aims to ensure that patients take a standard short-course of chemotherapy under guided supervision to cure the disease as well as to prevent transmission. Patients are assisted through their treatment regimen and encouraged to treatment completion in order to prevent resistance to the available anti-TB drugs. DOTS has been delivered by health workers, community volunteers, lay health workers and even family members [5]. For further details on TB burden, epidemiology and intervention coverage, refer to previous paper in this series [6].

Considering the recent shift in epidemiological presence of TB, there is a legitimate call for integration of therapeutic services especially with HIV [7]. Since both diseases require long term treatment regimens, community based support may play a defining role towards prevention and control of these syndemic diseases of poverty. Moreover, integration of services in low-income countries may prove beneficial in terms of cost-effectiveness and decrease demand on health service infrastructure. However, there is a need to gauge whether these strategies lead to effective treatment outcomes. This paper aims to evaluate the effectiveness of community based interventions (CBI) for the prevention and treatment of TB.

Methods

We systematically reviewed literature published by September 2013 to identify studies evaluating CBI for TB as outlined in our conceptual framework [8]. Our priority was to select existing randomized controlled trials (RCT), quasi-experimental and before/after studies in which the intervention was delivered within community settings and the reported outcomes were relevant. A comprehensive search strategy was developed using appropriate key words, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free text terms. The search was conducted in PubMed, Cochrane libraries, EMBASE and WHO Regional Databases; additional studies were identified by hand searching references from included studies. Studies were excluded if the intervention was purely facility-based or had a facility-based component. Studies that met the inclusion criteria were selected and double data abstracted on a standardized abstraction sheet. Quality assessment of the included RCT was done using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool [9]. We conducted meta-analysis for individual studies using the software Review Manager 5.1. Pooled statistics were reported as the relative risk (RR) for categorical variables and standard mean difference (SMD) for continuous variables between the experimental and control groups with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Subgroup analysis was conducted for therapeutic and preventive (screening) CBI, integrated and non-integrated CBI and by type of studies. The detailed methodology is described in previous paper [8].

Review

A total of 7,772 titles were identified from all databases and 107 full texts were screened. After screening, forty one [10–50] studies met the inclusion criteria; 34 RCT and 7 before/after studies (Figure 1). From the included RCT, 18 were adequately randomized while five studies reported adequate sequence generation (Table 1). Due to the nature of the intervention, blinding of the participants and assessors was not possible. Studies provided insufficient information on selective reporting which limited us from making any judgment. Ten of the included studies focused on TB prevention and case detection while 31 studies were on treatment of patients with active TB. Interventions involved community based delivery of DOTS; community mobilization and support; education and training; and monetary incentives for treatment adherence. Most of the CBI utilized community health workers (CHW) or family members as part of the delivery strategy. Table 2 describes the characteristics of included studies.

Quantitative synthesis

Overall, CBI for TB prevention and case detection showed significant increase in TB detection rates (RR: 3.1, 95% CI: 2.92, 3.28) (Figure 2) while there was a non-significant impact on TB incidence, although this evidence is from a single study. Subgroup analysis showed consistent results for various study designs and whether the interventions were delivered in an integrated or a non-integrated manner. CBI for treating patients with active TB showed an overall improvement in treatment success rates (RR: 1.09, 95% CI: 1.07, 1.11) (Figure 3) and evidence from a single study suggests significant reduction in relapse rate (RR 0.26, 95% CI: 0.18, 0.39). The results were consistent for various study design and delivery mechanism. The results are summarized in Table 3.

Qualitative synthesis

Included studies suggest that CBI for TB have the potential to improve access to diagnostic and treatment services for poor rural communities and vulnerable population including women and children. Community based TB treatment delivery through CHW not only improved access and service utilization but also contributed to capacity building and improving routine TB recording and reporting systems through regular supportive supervision [34]. Better outcomes were reported when DOTS was provided together with CHW program as it enabled treatment continuation; thus achieving higher treatment success rates [21]. Studies also support the feasibility of integrating cadres of CHW through establishing supportive structures and supervision [28, 29]. Besides treatment, community based untargeted periodic active case finding for symptomatic smear-positive TB also made a substantial contribution to diagnosis and control of infectious TB [17]. This is a significant finding as the slow rate at which patients with tuberculosis report to health facilities is a major limitation in global efforts to control TB. However, especial emphasis needs to be given for training, close supervision and support for CHW to achieve job satisfaction and sustainability [34].

Despite considerable advocacy for increased collaboration and integration of TB and HIV care, few models of integration have been implemented, evaluated and reported [11, 17, 20, 28, 29]. However, existing evidence favors integrating TB and HIV care for improving active case finding and early diagnosis of TB, which in turn, reduces the risk of TB transmission [28]. TB/HIV co-infected patients receiving concurrent antiretroviral and TB therapy achieved high levels of adherence and excellent TB and HIV outcomes [28]. Integrated provision of TB, HIV and prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) services at community level through CHW is feasible, acceptable and successful [28, 29]. Training CHW to provide a comprehensive package of TB ⁄HIV⁄PMTCT prevention, case finding and treatment support services can bridge the current gaps in service delivery through vertical TB, HIV and PMTCT programs. Evidence also suggests that DOTS strategy can be successfully implemented at primary health care clinics [31]. However such integrations should follow careful planning and caution with greater investments in developing and implementing infection control and laboratory infrastructure [28].

Key components reported for a successful community delivery strategy to prevent and treat TB included a preexisting TB DOTS infrastructure, patient treatment literacy training, and adherence support from trained CHW and family members [21]. Involvement of non-governmental organization (NGO) has also been reported as an essential component of TB programs [22]. Formation of community groups also have reported to contribute towards improved awareness and knowledge about TB and treatment adherence. Community groups help bridge gaps between health system and community through support and coordination. Multi-sectoral community mobilization events that engage community leaders is also one of the enabling tools for successful community based programs in TB⁄HIV⁄PMTCT care [28, 29]. Engagement of successfully treated patients can also assist in reducing community stigma and discrimination [22]. Other strategies for organizing, coordinating and managing health care include continuous education and direct supervision of health providers; establishment of goals and regular monitoring of process and result indicators; and incentives for effective use of recommended guidelines [21].

One of the major reported barriers in the success of TB programs is non-adherence mainly due to the lack of support. The intensity of support for patients is reported to diminish in the continuation phase of treatment [11]. Lack of incentives, difficult treatment access, poor communication between health providers and patients, poor application of DOTS, lack of active search for missing patients, and limitations of supervision in treatment units are recognized barriers to treatment success [21]. In addition, the presence of multiple cadres of CHW providing TB and HIV services in silos has hindered the enhancement of collaborative TB⁄HIV activities in community, as well as their supervision [28, 29]. Inconsistency in the supply of commodities such as test kits need to be resolved to increase uptake of HIV testing and counseling [28, 29].

Discussion

Our review findings suggest that CBI are effective in TB detection and treatment but its role in preventing TB cases has not been comprehensively evaluated. Community based delivery of DOTS may be more feasible and effective for TB case detection and treatment as community workers are familiar with the layout of community and have community member’s trust which healthcare officials would have to develop. Moreover, a community-based approach helps empower each community to deal with its own problems and also provides patient with a greater degree of autonomy and satisfaction with the treatment regime [51]. This involvement of respected, responsible and resourceful community and family members increases the trust that is required to initiate treatment and provides close supervision thereby maximizing adherence which is crucial in such a lengthy treatment regime. Limited coverage of public health services has continued to impede accelerated access to TB control services due to inadequate health service infrastructure, insufficient decentralization of services and inadequate human, material and financial resources. Hence, community delivery platforms offer improved access and equitable distribution of care.

High incidence of TB and its significant financial burden makes it imperative to find a plausible strategy to cope with this disease. The fact that it effects lower socio-economic groups further compounds the problem. Gender inequality, social stigma, and poverty are also recognized as important barriers for successful TB prevention and control programs [52–55]. In light of the above situation, DOTS provides a successful and cost-effective strategy to deal with the burden of TB [27, 30, 41]. CBI coupled with DOTS seems to be an effective approach as they have the potential to maximize the outreach and minimize the cost. Community based TB control also offers many lessons for the control of HIV epidemic. With the emergence of HIV and consequent TB resurgence, a comprehensive and equitable strategy is needed to stem the worsening double burden of these two infections in poor countries [56].

The WHO currently advocates home-based care and integrated management of dually infected TB/AIDS patients [57]. It recommends a 12 point package of collaborative TB/HIV activities based on creating a mechanism of collaboration between TB and HIV programs, reducing the burden of TB among people living with HIV and reducing the burden of HIV among TB patients. CHW delivering DOTS can be further trained to carry out this additional task and studies are needed to evaluate the feasibility, relative effectiveness and cost effectiveness of this approach [23, 58]. However, such integration would involve CHW training and time; improved collaboration between community and facility; and strengthening referral services [59, 60].

Conclusion

Well-designed operational research is needed to pragmatically evaluate various models of community based delivery. There is a need to evaluate and address context specific barriers to community based implementation, especially for collaborative TB⁄HIV activities in the community to avoid duplication of labor and resources. Future studies should focus on evaluating novel community delivery models for their success in larger and more diverse populations and impact TB prevention and active case detection.

Abbreviations

- CBI:

-

Community based interventions

- CHW:

-

Community health workers

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DOTS:

-

Direct observed therapy

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- MDR-TB:

-

Multi drug resistant tuberculosis

- NGO:

-

Non-governmental organization

- PMTCT:

-

Prevention of mother-to-child transmission

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- RR:

-

Relative risk

- SMD:

-

Standard mean difference

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- WHO:

-

World Health organization.

References

World Health Organization: Global Tuberculosis Report. 2013, Availabel at http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/91355/1/9789241564656_eng.pdf?ua=1

WHO: Global Tuberculosis Control: Epidemiology, Strategy, Financing: WHO, 2009. 2009, Geneva, Switzerland: WHO

Rose AM, Watson JM, Graham C, Nunn AJ, Drobniewski F, Ormerod LP, Darbyshire JH, Leese J: Tuberculosis at the end of the 20th century in England and Wales: results of a national survey in 1998. Thorax. 2001, 56 (3): 173-179.

Schluger NW, Burzynski J: Tuberculosis and HIV infection: epidemiology, immunology, and treatment. HIV Clin Trials. 2001, 2 (4): 356-365.

WHO: Community contribution to TB care: practice and policy. WHO. 2003, Geneva: World Health Organization

Bhutta ZA, Sommerfeld J, Lassi ZS, Salam RA, Das JK: Global burden, distribution and interventions for the infectious diseases of poverty. Infect Dis Pov. 2014, 3: 21

Wood R: The case for integrating tuberculosis and HIV treatment services in South Africa. J Infect Dis. 2007, 196 (Suppl 3): S497-S499.

Lassi ZS, Salam RA, Das JK, Bhutta ZA: Conceptual framework and assessment methodology for the systematic review on community based interventions for the prevention and control of IDoP. Infect Dis Pov. 2014, 3: 22

Higgins JPT, Green S: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from [http://www.cochrane-handbook.org]

Amo-Adjei J, Awusabo-Asare K: Reflections on tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment outcomes in Ghana. Arch Public Health. 2013, 71 (1): 22

Atkins S, Lewin S, Jordaan E, Thorson A: Lay health worker-supported tuberculosis treatment adherence in South Africa: an interrupted time-series study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011, 15 (1): 84-89. i

Barker RD, Millard FJ, Nthangeni ME: Unpaid community volunteers–effective providers of directly observed therapy (DOT) in rural South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2002, 92 (4): 291-294.

Brust JC, Shah NS, Scott M, Chaiyachati K, Lygizos M, van der Merwe TL, Bamber S, Radebe Z, Loveday M, Moll AP, Margot B, Lalloo UG, Friedland GH, Gandhi NR: Integrated, home-based treatment for MDR-TB and HIV in rural South Africa: an alternate model of care. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012, 16 (8): 998-1004.

Cantalice Filho JP: Food baskets given to tuberculosis patients at a primary health care clinic in the city of Duque de Caxias, Brazil: effect on treatment outcomes. J Bras Pneumol. 2009, 35 (10): 992-997.

Clarke M, Dick J, Zwarenstein M, Lombard CJ, Diwan VK: Lay health worker intervention with choice of DOT superior to standard TB care for farm dwellers in South Africa: a cluster randomised control trial. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005, 9 (6): 673-679.

Colvin M, Gumede L, Grimwade K, Maher D, Wilkinson D: Contribution of traditional healers to a rural tuberculosis control programme in Hlabisa, South Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2003, 7 (9 Suppl 1): S86-S91.

Corbett EL, Bandason T, Duong T, Dauya E, Makamure B, Churchyard GJ, Williams BG, Munyati SS, Butterworth AE, Mason PR, Mungofa S, Hayes RJ: Comparison of two active case-finding strategies for community-based diagnosis of symptomatic smear-positive tuberculosis and control of infectious tuberculosis in Harare, Zimbabwe (DETECTB): a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2010, 376 (9748): 1244-1253.

Diez E, Claveria J, Serra T, Cayla JA, Jansa JM, Pedro R, Villalbi JR: Evaluation of a social health intervention among homeless tuberculosis patients. Tuber Lung Dis. 1996, 77 (5): 420-424.

Dudley L, Azevedo V, Grant R, Schoeman JH, Dikweni L, Maher D: Evaluation of community contribution to tuberculosis control in Cape Town, South Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2003, 7 (9 Suppl 1): S48-S55.

Fairall LR, Zwarenstein M, Bateman ED, Bachmann M, Lombard C, Majara BP, Joubert G, English RG, Bheekie A, van Rensburg D, Mayers P, Peters AC, Chapman RD: Effect of educational outreach to nurses on tuberculosis case detection and primary care of respiratory illness: pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2005, 331 (7519): 750-754.

Ferreira V, Brito C, Portela M, Escosteguy C, Lima S: DOTS in primary care units in the city of Rio de Janeiro. Southeastern Brazil Rev Saude Publica. 2011, 45 (1): 40-48.

Kamineni VV, Turk T, Wilson N, Satyanarayana S, Chauhan LS: A rapid assessment and response approach to review and enhance advocacy, communication and social mobilisation for tuberculosis control in Odisha state. India BMC Public Health. 2011, 11: 463

Kironde S, Kahirimbanyi M: Community participation in primary health care (PHC) programmes: lessons from tuberculosis treatment delivery in South Africa. Afr Health Sci. 2002, 2 (1): 16-23.

Mafigiri DK, McGrath JW, Whalen CC: Task shifting for tuberculosis control: a qualitative study of community-based directly observed therapy in urban Uganda. Glob Public Health. 2012, 7 (3): 270-284.

Miti S, Mfungwe V, Reijer P, Maher D: Integration of tuberculosis treatment in a community-based home care programme for persons living with HIV/AIDS in Ndola. Zambia Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2003, 7 (9 Suppl 1): S92-S98.

Niazi AD, Al-Delaimi AM: Impact of community participation on treatment outcomes and compliance of DOTS patients in Iraq. East Mediterr Health J. 2003, 9 (4): 709-717.

Prado TN, Wada N, Guidoni LM, Golub JE, Dietze R, Maciel EL: Cost-effectiveness of community health worker versus home-based guardians for directly observed treatment of tuberculosis in Vitoria, Espirito Santo State. Brazil Cad Saude Publica. 2011, 27 (5): 944-952.

Uwimana J, Zarowsky C, Hausler H, Jackson D: Training community care workers to provide comprehensive TB/HIV/PMTCT integrated care in KwaZulu-Natal: lessons learnt. Trop Med Int Health. 2012, 17 (4): 488-496.

Uwimana J, Zarowsky C, Hausler H, Swanevelder S, Tabana H, Jackson D: Community-based intervention to enhance provision of integrated TB-HIV and PMTCT services in South Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013, 17 (10 Suppl 1): 48-55.

Vassall A, Bagdadi S, Bashour H, Zaher H, Maaren PV: Cost-effectiveness of different treatment strategies for tuberculosis in Egypt and Syria. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002, 6 (12): 1083-1090.

Vieira AA, Ribeiro SA: Compliance with tuberculosis treatment after the implementation of the directly observed treatment, short-course strategy in the city of Carapicuiba. Brazil J Bras Pneumol. 2011, 37 (2): 223-231.

Weis SE, Slocum PC, Blais FX, King B, Nunn M, Matney GB, Gomez E, Foresman BH: The effect of directly observed therapy on the rates of drug resistance and relapse in tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 1994, 330 (17): 1179-1184.

White MC, Tulsky JP, Goldenson J, Portillo CJ, Kawamura M, Menendez E: Randomized controlled trial of interventions to improve follow-up for latent tuberculosis infection after release from jail. Arch Intern Med. 2002, 162 (9): 1044-1050.

Yassin MA, Datiko DG, Tulloch O, Markos P, Aschalew M, Shargie EB, Dangisso MH, Komatsu R, Sahu S, Blok L, Cuevas LE, Theobald S: Innovative community-based approaches doubled tuberculosis case notification and improve treatment outcome in Southern Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2013, 8 (5): e63174

Zwarenstein M, Schoeman JH, Vundule C, Lombard CJ, Tatley M: A randomised controlled trial of lay health workers as direct observers for treatment of tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000, 4 (6): 550-554.

Group C: Community-directed interventions for priority health problems in Africa: results of a multicountry study. Bull World Health Organ. 2010, 88 (7): 509-518.

Chaisson RE, Barnes GL, Hackman J, Watkinson L, Kimbrough L, Metha S, Cavalcante S, Moore RD: A randomized, controlled trial of interventions to improve adherence to isoniazid therapy to prevent tuberculosis in injection drug users. Am J Med. 2001, 110 (8): 610-615.

Gandhi NR, Moll AP, Lalloo U, Pawinski R, Zeller K, Moodley P, Meyer E, Friedland G: Successful integration of tuberculosis and HIV treatment in rural South Africa: the Sizonq'oba study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009, 50 (1): 37-43.

Heal G, Elwood RK, FitzGerald JM: Acceptance and safety of directly observed versus self-administered isoniazid preventive therapy in aboriginal peoples in British Columbia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1998, 2 (12): 979-983.

Kamolratanakul P, Sawert H, Lertmaharit S, Kasetjaroen Y, Akksilp S, Tulaporn C, Punnachest K, Na-Songkhla S, Payanandana V: Randomized controlled trial of directly observed treatment (DOT) for patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in Thailand. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999, 93 (5): 552-557.

Khan MA, Walley JD, Witter SN, Imran A, Safdar N: Costs and cost-effectiveness of different DOT strategies for the treatment of tuberculosis in Pakistan. Directly Observed Treatment. Health Policy Plan. 2002, 17 (2): 178-186.

Lwilla F, Schellenberg D, Masanja H, Acosta C, Galindo C, Aponte J, Egwaga S, Njako B, Ascaso C, Tanner M, Alonso P: Evaluation of efficacy of community-based vs. institutional-based direct observed short-course treatment for the control of tuberculosis in Kilombero district, Tanzania. Trop Med Int Health. 2003, 8 (3): 204-210.

MacIntyre CR, Goebel K, Brown GV, Skull S, Starr M, Fullinfaw RO: A randomised controlled clinical trial of the efficacy of family-based direct observation of anti-tuberculosis treatment in an urban, developed-country setting. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2003, 7 (9): 848-854.

Malotte CK, Hollingshead JR, Larro M: Incentives vs outreach workers for latent tuberculosis treatment in drug users. Am J Prev Med. 2001, 20 (2): 103-107.

Newell JN, Baral SC, Pande SB, Bam DS, Malla P: Family-member DOTS and community DOTS for tuberculosis control in Nepal: cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006, 367 (9514): 903-909.

Olle-Goig JE, Alvarez J: Treatment of tuberculosis in a rural area of Haiti: directly observed and non-observed regimens. The experience of H pital Albert Schweitzer. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001, 5 (2): 137-141.

Walley JD, Khan MA, Newell JN, Khan MH: Effectiveness of the direct observation component of DOTS for tuberculosis: a randomised controlled trial in Pakistan. Lancet. 2001, 357 (9257): 664-669.

Wandwalo E, Kapalata N, Egwaga S, Morkve O: Effectiveness of community-based directly observed treatment for tuberculosis in an urban setting in Tanzania: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004, 8 (10): 1248-1254.

Wright J, Walley J, Philip A, Pushpananthan S, Dlamini E, Newell J, Dlamini S: Direct observation of treatment for tuberculosis: a randomized controlled trial of community health workers versus family members. Trop Med Int Health. 2004, 9 (5): 559-565.

Zwarenstein M, Schoeman JH, Vundule C, Lombard CJ, Tatley M: Randomised controlled trial of self-supervised and directly observed treatment of tuberculosis. Lancet. 1998, 352 (9137): 1340-1343.

WHO: Community Involvement in Tuberculosis Care and Prevention. Towards Partnerships for Health. 2008, Available at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596404_eng.pdf

Atre SR, Kudale AM, Morankar SN, Rangan SG, Weiss MG: Cultural concepts of tuberculosis and gender among the general population without tuberculosis in rural Maharashtra. India Trop Med Int Health. 2004, 9 (11): 1228-1238.

Long NH, Johansson E, Diwan VK, Winkvist A: Fear and social isolation as consequences of tuberculosis in VietNam: a gender analysis. Health Policy. 2001, 58 (1): 69-81.

Weiss MG, Somma D, Karim F, Abouihia A, Auer C, Kemp J, Jawahar MS: Cultural epidemiology of TB with reference to gender in Bangladesh, India and Malawi. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008, 12 (7): 837-847.

Aryal S, Badhu A, Pandey S, Bhandari A, Khatiwoda P, Khatiwada P, Giri A: Stigma related to tuberculosis among patients attending DOTS clinics of Dharan municipality. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2012, 10 (37): 48-52.

Farmer P, Laandre F, Mukherjee J, Gupta R, Tarter L, Kim JY: Community-based treatment of advanced HIV disease: introducing DOT-HAART (directly observed therapy with highly active antiretroviral therapy). Bull World Health Organ. 2001, 79 (12): 1145-1151.

World Health Organization: WHO Policy on Collaborative TB/HIV Activities: Guidelines for National Programmes and other Stakeholders. 2012, Geneva: World Health Organization

Kironde S: Tuberculosis. South African Health Review. Edited by: Ntuli A, Crisp N, Clarke E, Baron P. 2000, Durban: Health Systems Trust, 335-349.

Legido-Quigley H, Montgomery CM, Khan P, Atun R, Fakoya A, Getahun H, Grant AD: Integrating tuberculosis and HIV services in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2013, 18 (2): 199-211.

Howard AA, El-Sadr WM: Integration of tuberculosis and HIV services in sub-Saharan Africa: lessons learned. Clin Infect Dis. 2010, 50 (Supplement 3): S238-S244.

Acknowledgements

The collection of scoping reviews in this special issue of Infectious Diseases of Poverty was commissioned by the UNICEF/UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) in the context of a Contribution Agreement with the European Union for “Promoting research for improved community access to health interventions in Africa”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no financial or non-financial competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

ZAB was responsible for designing and coordinating the review. AA and IN were responsible for: data collection, screening the search results, screening retrieved papers against inclusion criteria, appraising quality of papers and abstracting data. RAS, JKD and ZSL were responsible for data interpretation and writing the review. ZAB critically reviewed and modified the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Arshad, A., Salam, R.A., Lassi, Z.S. et al. Community based interventions for the prevention and control of tuberculosis. Infect Dis Poverty 3, 27 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/2049-9957-3-27

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2049-9957-3-27