Abstract

Background

Pediatric injury is highly prevalent and has significant impact both physically and emotionally. The majority of pediatric injuries are treated in emergency departments (EDs), where treatment of physical injuries is the main focus. In addition to physical trauma, children often experience significant psychological trauma, and the development of acute stress disorder (ASD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is common. The consequences of failing to recognize and treat children with ASD and PTSD are significant and extend into adulthood. Currently, screening guidelines to identify children at risk for developing these stress disorders are not evident in the pediatric emergency setting. The goal of this systematic review is to summarize evidence on the psychometric properties, diagnostic accuracy, and clinical utility of screening tools that identify or predict PTSD secondary to physical injury in children. Specific research objectives are to: (1) identify, describe, and critically evaluate instruments available to screen for PTSD in children; (2) review and synthesize the test-performance characteristics of these tools; and (3) describe the clinical utility of these tools with focus on ED suitability.

Methods

Computerized databases including MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, ISI Web of Science and PsycINFO will be searched in addition to conference proceedings, textbooks, and contact with experts. Search terms will include MeSH headings (post-traumatic stress or acute stress), (pediatric or children) and diagnosis. All articles will be screened by title/abstract and articles identified as potentially relevant will be retrieved in full text and assessed by two independent reviewers. Quality assessment will be determined using the QUADAS-2 tool. Screening tool characteristics, including type of instrument, number of items, administration time and training administrators level, will be extracted as well as gold standard diagnostic reference properties and any quantitative diagnostic data (specificity, positive and negative likelihood/odds ratios) where appropriate.

Discussion

Identifying screening tools to recognize children at risk of developing stress disorders following trauma is essential in guiding early treatment and minimizing long-term sequelae of childhood stress disorders. This review aims to identify such screening tools in efforts to improve routine stress disorder screening in the pediatric ED setting.

Trials registration

PROSPERO registration: CRD42013004893

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pediatric injury is highly prevalent and has significant impact. Injuries are the largest cause of morbidity and mortality among children in the United States and Canada, and are the leading cause of emergency department (ED) visits for children greater than 1 year of age [1–3]. Injury-related ED visits in the United States are estimated to range from 63 to 165 per 1,000 children [4]. The vast majority of pediatric injuries are treated acutely in EDs with a strong focus on physical trauma.

The prevalence of stress disorders such as acute stress disorder (ASD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following injury is high. Some children with sub-clinical features suffer as much distress and impairment as those diagnosed with full PTSD, and the risk factors to identify those children at greatest risk for subsequent development of PTSD have been outlined [5]. Recent research has demonstrated that up to 68% of all children experience potentially traumatic events, with more than half of these children experiencing multiple events [6]. A recent systematic review of 21 single-center cohort studies reported the prevalence of PTSD among pediatric survivors of motor vehicle accidents (MVA) to be between 12% and 46% at 4 months post-MVA and 13 to 25% at 12 months post-MVA [7]. A prospective cohort study of children experiencing orthopedic trauma including bone fractures secondary to falls, sporting injuries or MVAs found that 33% of the cohort experienced PTSD at 1 year follow-up [8]. Historically it was thought that PTSD symptoms would only develop after experiencing trauma resulting in severe injury. It has recently been discovered, through cohort studies in children, that these considerably high rates of ASD and PTSD do not seem to depend on the nature or the severity of the injury sustained [7] and even mild trauma can have long-lasting effects [8–10]. Explanations for this are variable, multifactorial and complex, but biological plausibility for this effect is present [11]. Some individuals may be identifiably at higher risk for the development of subsequent stress disorders because of key pre-traumatic, peri-traumatic, and post-traumatic factors that are individually specific but that over a population are identifiable.

The consequences of failing to recognize and treat children at risk for PTSD are stark and prevail into adult life. PTSD is linked to changes in neurobiology [12, 13] during development and highly correlated with poor quality of life [14]. Long-term consequences of unrecognized and untreated ASD and PTSD include increased lifetime risk of poor school performance, impaired development, aggression, risk-taking behaviors, depression, suicidal ideation, increased adult mental illness and increased adult physical illness [15–19].

The ED is usually the first and is often the only point of medical care for children experiencing a physical trauma. Thus, the ED visit may be the best opportunity to screen for PTSD vulnerability and to connect patients to resources for future interventions or treatments [20, 21]. Such screening, however, is not current practice in this setting. In 2008, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) released a position statement on the management of pediatric trauma stating that psychological support is a vital component of pediatric trauma care [22]. The AAP has also recently released a report describing the importance of the role of ED healthcare professionals in the stabilization and discovery of pediatric mental health, and advocating for improved recognition and treatment of mental health needs [23]. Despite these strong recommendations, psychological support as a component of follow-up for pediatric trauma is lacking or absent [24, 25]. Reasons for this are variable, but time pressures and lack of awareness of appropriate screening tools are key contributors. This review aims to address this deficiency by conducting a comprehensive review in order to identify PTSD screening tools that are suitable for use in the pediatric ED setting. Specific research objectives are to: (1) identify, describe, and critically evaluate instruments available to screen for PTSD in children and adolescents; (2) review and synthesize the test-performance characteristics of these tools; and (3) describe the clinical utility of these tools with particular focus on suitability for ED use. A broad systematic synthesis of the evidence regarding the availability and performance of available tools applicable to this very important setting does not yet exist.

Methods

The systematic review protocol has been registered with the PROSPERO systematic review database (registration number CRD42013004893) and has been designed based on the PRISMA statement and guidelines established in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0.

Search strategy/data sources

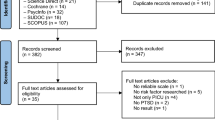

Database searches will be executed by a medical librarian (SC) using subject headings (for example, MESH, EMTREE) and text words to retrieve articles related to the following concepts: (post-traumatic stress or acute stress) and (pediatric or children) and diagnosis. Databases searched will include: MEDLINE, EMBASE, EBM Reviews (Cochrane database of systematic reviews, ACP journal club, Database of abstracts of reviews of effects, Cochrane central register of controlled trials, Cochrane methodology register, Health technology assessment, NHS economic evaluation database), Global Health, PsycINFO, Health and Psychosocial Instruments, ProQuest dissertations and theses as well as conference proceedings and contact with experts in the field. An additional search of gray literature will include Google Scholar and related field websites in pediatric mental health with screening tools evaluating PTSD in children. There will be no restrictions for articles by language, publication date or publication status. All references will be exported to RefWorks citation management software, where duplicates will be verified, recorded and removed. Search strategies are listed in Additional file 1: Appendix 3.

Study selection

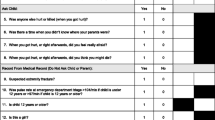

Two independent reviewers will screen all articles by title and abstract against inclusion and exclusion criteria described in Table 1. Any discrepancies between the two reviewers throughout the screening/selection process will be resolved by discussion and consultation with a third reviewer. Articles identified as potentially relevant will be retrieved for full text review and all non-English articles will be translated appropriately. Detailed eligibility forms (Additional file 1: Appendix 1) will be completed for all potentially relevant articles to confirm eligibility criteria and record details of excluded articles.

Types of interventions, participants, and study designs

Screening tools, instruments, or questionnaires implemented after traumatic events with the purpose of identifying children/adolescents (<18 years) at risk for developing PTSD are eligible. Such measures, with diagnostic and psychometric study designs, will be described and evaluated. Studies will clearly describe the gold-standard criteria by which a diagnosis of PTSD was made (diagnostic studies) [26] or comparison instruments (psychometric studies) [27].

Data extraction and analysis

Two reviewers will utilize a customized data extraction form (Additional file 1: Appendix 2) based on a modified version of the Social-Emotional Tool described by Gokiert and colleagues [28]. Across all studies, screening tool characteristics will be extracted and described (for example, types of questions, length) as will characteristics about the population used to develop and evaluate the intervention and the setting in which it was evaluated. Where psychometric data are provided, reliability and validity data will be extracted and summarized. Where diagnostic data are provided, the following will be calculated: (1) sensitivity (with 95% CIs), (2) specificity (with 95% CIs), (3) likelihood ratios (with 95% CIs), (4) diagnostic odds ratios (with 95% CIs), and (5) receiver operating characteristic curves. To assess potential discrepancy between differences in the reliability of the diagnostic gold standard used between studies, subgroup analysis will be preformed according to the QUADAS-2 tool [26] for assessment of risk of bias and applicability.

Quality assessment

Review of citations/abstracts, included articles, data extraction, and quality rating will be performed by two team members using customized forms with pre-determined criteria (Additional file 1: Appendices 1 and 2); inter-rater reliability (kappa statistic) will be measured. Where possible, diagnostic data will be arranged in 2 × 2 tables to calculate the above outcome measures and pooled to produce summary likelihood ratios for positive and negative test results. Quality of included studies will be determined using the QUADAS-2 tool for assessment of diagnostic accuracy in systematic reviews. Heterogeneity will be explored and subgrouping, meta-regression, or graphical methods will be employed if warranted. The degree of heterogeneity via I2 statistic will be calculated when applicable. If substantial heterogeneity exists (I2 > 25%), subgrouping by demographics (age, gender, location) and meta-regression analysis will be attempted.

Discussion

The ED is a unique environment. The pace, range of conditions and stress is high. Healthcare providers have multiple competing care duties and the chances of successfully implementing a screening tool into clinical care pathways for pediatric traumatic events will be maximized if the tool is carefully selected to suit the environment while maintaining accuracy in diagnosis to ensure improved outcomes. Given that pediatric injury is so prevalent and that EDs support the vast majority of these injuries acutely, it is logical for clinicians familiar with this unique environment and its patients to review and select the most suitable tool possible. To date, we are unaware of the availability of any such comprehensive review pertaining to the use of such tools in the acute-care ED. This review will address this deficiency by identifying, describing and evaluating such tools and comparing their features in a concise table. We will make screening recommendations based on the tools described and provide a foundation for the development of future practice guidelines in the psychological management of pediatric injury.

Abbreviations

- AAP:

-

American Academy of Pediatrics

- ASD:

-

acute stress disorder

- ED:

-

emergency department

- MVA:

-

motor vehicle accidents

- PTSD:

-

post-traumatic stress disorder.

References

Benahmed N, Laokri S, Zhang WH, Verhaeghe N, Trybou J, Cohen L, De Wever A, Alexander S: Determinants of nonurgent use of the emergency department for pediatric patients in 12 hospitals in Belgium. Eur J Pediatr. 1829–1837, 2012: 171-

Safe Kids Canada: Updated July 2007. Child & Youth Unintentional Injury 10 Years in Review 1994–2003. 2007, Canada: Safe Kids Canada

Public Health Agency of Canada: 2009 Edition. Child and Youth Injury in Review Spotlight on Consumer Product Safety. 2009, Canada: Public Health Agency of Canada, 45-47.

Owens PL, Zodet MW, Berdahl T, Dougherty D, McCormick MC, Simpson LA: Annual report on health care for children and youth in the United States: focus on injury-related emergency department utilization and expenditures. Ambul Pediatr. 2008, 8: 219-240. 10.1016/j.ambp.2008.03.032.

Trickey D, Siddaway AP, Meiser-Stedman R, Serpell L, Field AP: A meta-analysis of risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012, 32: 122-138. 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.12.001.

Copeland WE, Keeler G, Angold A, Costello EJ: Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007, 64: 577-584. 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.577.

Mehta S, Ameratunga SN: Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder among children and adolescents who survive road traffic crashes: a systematic review of the international literature. J Paediatr Child Health. 2012, 48: 876-885. 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2011.02076.x.

Wallace M, Puryear A, Cannada LK: An evaluation of posttraumatic stress disorder and parent stress in children with orthopaedic injuries. J Orthop Trauma. 2013, 27: e38-e41. 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318250c837.

Di Gallo A, Parry-Jones WL: Psychological sequelae of road traffic accidents: an inadequately addressed problem. Br J Psychiatry. 1996, 169: 405-407. 10.1192/bjp.169.4.405.

Sanders MB, Starr AJ, Frawley WH, McNulty MJ, Niacaris TR: Posttraumatic stress symptoms in children recovering from minor orthopaedic injury and treatment. J Orthop Trauma. 2005, 19: 623-628. 10.1097/01.bot.0000174709.95732.1b.

Morris MC, Rao U: Psychobiology of PTSD in the acute aftermath of trauma: integrating research on coping, HPA function and sympathetic nervous system activity. Asian J Psychiatr. 2013, 6: 3-21. 10.1016/j.ajp.2012.07.012.

Diseth TH: Dissociation in children and adolescents as reaction to trauma - an overview of conceptual issues and neurobiological factors. Nord J Psychiatry. 2005, 59: 79-91. 10.1080/08039480510022963.

Diseth TH, Christie HJ: Trauma-related dissociative (conversion) disorders in children and adolescents - an overview of assessment tools and treatment principles. Nord J Psychiatry. 2005, 59: 278-292. 10.1080/08039480500213683.

Kiely JM, Brasel KJ, Weidner KL, Guse CE, Weigelt JA: Predicting quality of life six months after traumatic injury. J Trauma. 2006, 61: 791-798. 10.1097/01.ta.0000239360.29852.1d.

Boscarino JA: Post-traumatic stress disorder and cardiovascular disease link: time to identify specific pathways and interventions. Am J Cardiol. 2011, 108: 1052-1053.

Boscarino JA: PTSD is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease: time for increased screening and clinical intervention. Prev Med. 2012, 54: 363-364. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.01.001. Author reply 365

Panagioti M, Gooding PA, Tarrier N: A meta-analysis of the association between posttraumatic stress disorder and suicidality: the role of comorbid depression. Compr Psychiatry. 2012, 53: 915-930. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.02.009.

Perkonigg A, Owashi T, Stein MB, Kirschbaum C, Wittchen HU: Posttraumatic stress disorder and obesity: evidence for a risk association. Am J Prev Med. 2009, 36: 1-8. 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.026.

Zatzick DF, Grossman DC, Russo J, Pynoos R, Berliner L, Jurkovich G, Sabin JA, Katon W, Ghesquiere A, McCauley E, Rivara FP: Predicting posttraumatic stress symptoms longitudinally in a representative sample of hospitalized injured adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006, 45: 1188-1195. 10.1097/01.chi.0000231975.21096.45.

Strawn JR, Keeshin BR, DelBello MP, Geracioti TD, Putnam FW: Psychopharmacologic treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010, 71: 932-941. 10.4088/JCP.09r05446blu.

Wethington HR, Hahn RA, Fuqua-Whitley DS, Sipe TA, Crosby AE, Johnson RL, Liberman AM, Moscicki E, Price LN, Tuma FK, Kalra G, Chattopadhyay SK: The effectiveness of interventions to reduce psychological harm from traumatic events among children and adolescents: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2008, 35: 287-313. 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.024.

Krug SE, Tuggle DW: Management of pediatric trauma. Pediatrics. 2008, 121: 849-854.

Dolan MA, Fein JA: Pediatric and adolescent mental health emergencies in the emergency medical services system. Pediatrics. 2011, 127: e1356-e1366.

Banh MK, Saxe G, Mangione T, Horton NJ: Physician-reported practice of managing childhood posttraumatic stress in pediatric primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008, 30: 536-545. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.07.008.

Habis A, Tall L, Smith J, Guenther E: Pediatric emergency medicine physicians’ current practices and beliefs regarding mental health screening. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007, 23: 387-393. 10.1097/01.pec.0000278401.37697.79.

Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, Leeflang MM, Sterne JA, Bossuyt PM: QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011, 155: 529-536. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009.

Newton AS, Gokiert R, Mabood N, Ata N, Dong K, Ali S, Vandermeer B, Tjosvold L, Hartling L, Wild TC: Instruments to detect alcohol and other drug misuse in the emergency department: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2011, 128: e180-e192. 10.1542/peds.2010-3727.

Gokiert RJ, Georgis R, Tremblay M, Krishnan V, Vandenberghe C, Lee C: Evaluating the adequacy of social-emotional measures in early childhood. J Psychoed Asses. Jan 9, 2014, DOI: 10.1177/ 0734282913516718

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by a Women & Children’s Health Research Institute operating grant (SC) and a Women & Children’s Health Research Institute summer studentship (JO).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JO, the project lead, will complete PROSPERO registration, compile search results, remove duplicates, participate in screening, article retrieval, quality assessment and manuscript drafting. CC will participate in article screening, retrieval and quality assessment as well as provide revisions to the final manuscript. SC will develop and execute database search protocol and draft the database search manuscript methods section. SJC, AN, RG and CF initiated the project concept, will provide experience in evidence-based medicine methodology and data interpretation as well as contribute in manuscript preparation and review. SJC also drafted the initial review protocol and will act as third reviewer for article screening and inclusion. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

13643_2013_196_MOESM1_ESM.doc

Additional file 1: Appendix 1. Eligibility form for potentially relevant articles. Appendix 2. Data extraction form. Appendix 3. Search Strategy. (DOC 226 KB)

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Odenbach, J., Newton, A., Gokiert, R. et al. Screening for post-traumatic stress disorder after injury in the pediatric emergency department - a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev 3, 19 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-3-19

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-3-19