Abstract

Background

The development of clinical practice guidelines for managing spinal pain have been informed by a biopsychosocial framework which acknowledges that pain arises from a combination of psychosocial and biomechanical factors. There is an extensive body of evidence that has associated various psychosocial factors with an increased risk of experiencing persistent pain. Clinicians require instruments that are brief, easy to administer and score, and capable of validly identifying psychosocial factors. The pain diagram is potentially such an instrument. The aim of our study was to examine the association between pain diagram area and psychosocial factors.

Methods

183 adults, aged 20–85, with spinal pain were recruited. We administered a demographic checklist; pain diagram; 11-point Numerical Rating Scale assessing pain intensity; Pain Catastrophising Scale (PCS); MOS 36 Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36); and the Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ). Open source software, GIMP, was used to calculate the total pixilation area on each pain diagram. Linear regression was used to examine the relationship between pain diagram area and the following variables: age; gender; pain intensity; PCS total score; FABQ-Work scale score; FABQ-Activity scale score; and SF-36 Mental Health scale score.

Results

There were no significant associations between pain diagram area and any of the clinical variables.

Conclusion

Our findings showed that that pain diagram area was not a valid measure to identify psychosocial factors. Several limitations constrained our results and further studies are warranted to establish if pain diagram area can be used assess psychosocial factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The 2010 Global Burden of Disease study reported that musculoskeletal disorders ranked worldwide as the second leading cause of disability[1]. In considering individual conditions, the two most prevalent types of spinal pain, low back pain and neck pain, were respectively the leading, and fourth leading, source of disability-adjusted life years[1]. The extent of this problem leads to considerable socioeconomic burden in both direct medical costs and indirect costs[2].

The development of clinical practice guidelines for managing spinal pain have been informed by a biopsychosocial framework which acknowledges that pain arises from a combination of psychosocial and biomechanical factors[3–6]. About 80% of people seeking care for spinal pain will have non-specific spinal pain, for which assigning diagnostic labels is not recommended, and the approach to management depends on the clinician’s and patient’s preferences[6, 7].

Psychosocial factors encompass social and socio-occupational factors, psychological factors, cognitive and behavioural factors[8]. There is an extensive body of evidence that has associated various psychosocial factors with an increased risk of developing persistent pain, these include pain catastrophising; fear avoidance beliefs; anxiety; and depression[9–11].

Clinicians require instruments that are brief, easy to administer and score, and capable of validly identifying such psychosocial factors[10]. This information potentially enables clinicians to identify patients at risk of developing persistent pain and subsequently use targeted interventions that address psychosocial factors[12–14].

The pain diagram is one instrument that has been used to assess psychosocial factors[15]. It comprises front and back outlines of a body on which patients may mark areas that correspond to the distribution of pain (Figure 1). Several scoring methods have been used to identify psychosocial factors, including the Ransford Scoring System[16]; Modified Ransford Scoring System[17]; Pain Sites Scoring System[18]; and Body Map Scoring System[18]. However, none of these systems have been found to be valid measures[19].

One previous study has shown that the quantification of shaded pain diagram area can be reliably assessed and used to predict outcomes such as work absence and occupational disability[20]. Such findings have led to the inference that pain diagram area may be associated with psychosocial factors as these factors affect work absence and occupational disability. Scant research appears to have examined the relationship between pain diagram area and psychosocial factors that influence spinal pain. Therefore, the aim of our study was to examine the association between marked pain diagram area and two important psychosocial factors, pain catastrophising and fear-avoidance beliefs.

Methods

Study design

In this manuscript, we detail a secondary analysis which examined the relationship between the area marked on a pain diagram and psychosocial variables. The primary analysis examined adverse events resulting from chiropractic treatment and this has been published elsewhere[21, 22]. The trial was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12611000542998) and the protocol has been published[23]. All data were collected over one month between August and September 2011 at Murdoch University, Western Australia.

Recruitment and eligibility criteria

Newspaper advertisements were used to recruit participants from the local community. All participants were adults; English literate; experienced current spinal pain (neck, mid-back, or low back pain) of at least one week duration; and scored at least three out of a maximum 10 on the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) for pain[24], and 12 out of a maximum of 40 on the Functional Rating Index (FRI)[25].

We excluded participants who indicated they would be unwilling to tolerate any intervention possibly delivered in usual chiropractic care including: manipulative therapy; mobilisation; traction; massage; ultrasound; and physical modalities. Additional exclusion criteria were: spinal pain related to cancer or infection; spinal fracture; spondyloarthropathy; known osteoporosis; progressive upper or lower limb weakness; symptoms of cauda equina syndrome or other significant neurological condition; recent disc herniation; known severe cardiovascular disease; uncontrolled hypertension; cognitive impairment; blood coagulation disorder; previous spinal surgery in the past year; previous history of stroke or transient ischaemic attacks; pacemaker or other electrical device implanted; substance abuse issues; pregnancy; or a current compensation claim.

Baseline assessment

Full details about the administration of baseline and outcome measures have been reported elsewhere and the following section only contains details germane to this study[21, 22]. At baseline we administered a demographic checklist; pain diagram[15]; 11-point Numerical Rating Scale assessing pain intensity[24]; Pain Catastrophising Scale (PCS)[26]; Medical Outcomes Study 36 Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36)[27]; and the Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ)[28]. We used the posterior and anterior views of the human body seen on the pain diagram. Participants were asked to shade areas on the pain diagrams corresponding to where they were currently experiencing pain or discomfort. The SF-36 is a well validated and extensively used measure of general health status[27]. The NRS contains an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable). It is a valid, reliable and responsive measure of pain intensity[24]. The PCS assesses different dimensions of negative thoughts related to pain: rumination, magnification, and helplessness. The PCS has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure that predicts clinical outcomes[26]. The FABQ evaluates patient beliefs about the effect of physical activity and work on their experience of pain. The FABQ has good test-retest reliability, and predictive validity for future episodes of pain and clinical outcome[28].

Instrument of measurement

We used open source software, GIMP, to calculate the total marked pixilation area on each pain diagram[29]. It should be noted that only the pixels marked on the pain diagrams were counted. All pain diagrams were scanned and stored as JPEG files using RICOH Aficio MP4001 model scanner. GIMP’s automatic particle analysis function was then used to calculate the total number of pixels marked on each pain diagram[29]. A five step process using GIMP (version 2.6) was instituted. This included standardization of (i) size and (ii) colour, then (iii) determination of range of interest, (iv) defining different qualities of pixilation to a dichotomous choice. Pixel analysis with histogram function and quantification has been validated for objective quantification by Schönberger[30].

Ethics

Ethics approval was obtained from Murdoch University’s Human Research Committee (2011/109).

Data analysis

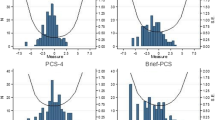

Data were analysed in SPSS v.21. Linear regression was used to examine the relationship between pain diagram area and the following variables: age; gender; pain intensity; PCS total score; FABQ-Work scale score; FABQ-Activity scale score; and SF-36 Mental Health scale score. Age, gender, and pain intensity were entered as covariates as they had been identified as effect modifiers in previous studies[19]. In addition, we constructed another linear regression model to examine the relationship between pain intensity and the following variables: PCS total score; FABQ-Work scale score; and FABQ-Activity scale score.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Baseline measures were completed by 183 participants. Table 1 displays the participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics. Most participants were male, and the majority had middle to high income levels and had completed secondary school.

Almost all patients (98%) had experienced spinal pain for more than three months. Three quarters (74%) had experienced spinal pain for more than five years. The vast majority (94%) stated it had been more than one year since last experiencing a four week pain free period, and over two thirds (69%) indicated it had been more than one year since their last one week pain free period.

Association of pain diagram with demographic and clinical characteristics

Table 2 displays the results of the linear regression analyses. There were no significant associations between marked pain diagram area and any of the demographic or clinical variables.

Associations between pain intensity and psychosocial factors

Table 3 displays the results of the linear regression analyses. Pain intensity was significantly associated with pain catastrophising and fear-avoidance work beliefs, but not significantly associated with fear-avoidance activity beliefs.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this was the first study to examine the relationship between pain diagram area, calculated by the use of computer software, and psychosocial factors. Although pain intensity was significantly associated with both fear-avoidance work beliefs and pain catastrophising, we observed no relationship between pain diagram area and pain catastrophising, fear-avoidance beliefs, and psychological health (assessed by the SF-36 Mental Health component score. Previous studies using different scoring systems to the system used in this study also found that pain diagrams could not validly identify the presence of psychosocial factors[15, 17, 18, 31–40].

One previous study had demonstrated a significant association between low SF-36 Mental Health component scores and pain diagrams that exhibited non-organic features based on the scoring system developed by Mann et al.[41]. This system classifies a pain diagram as nonorganic when the following features are observed: an excessive number of pain markings; a wide distribution of marks over many anatomic regions; marks outside the silhouette; and a disregard of instructions on what symbols to use. In cases where non-organic pain diagrams were identified, the odds ratio of obtaining a non-organic pain drawing was 22 when the Mental Health scale score was more than two standard deviations below the Danish norm. That finding suggests that the non-organic feature scoring system, in comparison to pain diagram area, is a superior method to identify psychological health through the use of pain diagrams. However, before this method could be confidently recommended, subsequent studies would be required to confirm the validity of using non-organic drawings to assess psychological distress.

Several limitations constrained the findings of this study. We did not assess test-retest reliability and are uncertain if this influenced our results. Another issue involves the participants using different types of ball point pens to fill out the pain diagram, and although these do not vary in a substantial way it is unclear as to what extent different pen tip widths may have affected the calculation of pain diagram area. Finally, the reliability of GIMP software has not been fully established, and so we are uncertain if this may have biased our results.

Conclusion

Our findings indicated that pixilation area on pain diagrams could not be used to identify psychosocial factors, but the study limitations raises uncertainty about the results and further studies are warranted. However, the procedure involved with calculating pixilation area was laborious and it is doubtful whether clinicians would be prepared to use the procedure even if it could be used assess psychosocial factors. Hence, we suggest that further research in this area is unlikely to be of great value, particularly as clinicians can readily identify patients in need of psychosocial interventions through the use of brief, validated instruments such as the Startback Screening Tool[42].

References

Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, Amann M, Anderson HR, Andrews KG, Aryee M: A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012, 380 (9859): 2224-2260. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8

Walker BF, Muller R, Grant WD: Low back pain in Australian adults. health provider utilization and care seeking. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2004, 27 (5): 327-335. 10.1016/j.jmpt.2004.04.006

Practitioners RCoG: Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Acute Low Back Pain. 1996, London: Royal College of General Practitioners,

Australian Acute Musculoskeletal Pain Guidelines Group: Evidence-based management of acute musculoskeletal pain. 2003, Australian Academic Press: Brisbane,

Centre for Clinical Excellence: Low back pain: early management of persistent non-specific low back pain. 2009,http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG88/NICEGuidance/pdf/English,

van Tulder M, Becker A, Bekkering T, Breen A, del Real MT, Hutchinson A, Koes B, Laerum E, Malmivaara A, : Chapter 3. European guidelines for the management of acute nonspecific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J. 2006, 15 (Suppl 2): S169-S191.

Turk DC: The potential of treatment matching for subgroups of patients with chronic pain: lumping versus splitting. Clin J Pain. 2005, 21 (1): 44-55. 10.1097/00002508-200501000-00006

Ramond A, Bouton C, Richard I, Roquelaure Y, Baufreton C, Legrand E, Huez JF: Psychosocial risk factors for chronic low back pain in primary care–a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2011, 28 (1): 12-21. 10.1093/fampra/cmq072

Vlaeyen JW, Morley S: Cognitive-behavioral treatments for chronic pain: what works for whom?. Clin J Pain. 2005, 21 (1): 1-8. 10.1097/00002508-200501000-00001

Boersma K, Linton SJ: Screening to identify patients at risk: profiles of psychological risk factors for early intervention. Clin J Pain. 2005, 21 (1): 38-43. 10.1097/00002508-200501000-00005

Boersma K, Linton SJ: Expectancy, fear and pain in the prediction of chronic pain and disability: a prospective analysis. Eur J Pain. 2006, 10 (6): 551-557. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.08.004

Boersma K, Linton SJ: How does persistent pain develop? An analysis of the relationship between psychological variables, pain and function across stages of chronicity. Behav Res Ther. 2005, 43 (11): 1495-1507. 10.1016/j.brat.2004.11.006

Linton SJ, Boersma K, Jansson M, Svard L, Botvalde M: The effects of cognitive-behavioral and physical therapy preventive interventions on pain-related sick leave: a randomized controlled trial. Clin J Pain. 2005, 21 (2): 109-119. 10.1097/00002508-200503000-00001

Jellema P, van der Windt DA, van der Horst HE, Blankenstein AH, Bouter LM, Stalman WA: Why is a treatment aimed at psychosocial factors not effective in patients with (sub)acute low back pain?. Pain. 2005, 118 (3): 350-359. 10.1016/j.pain.2005.09.002

Chan CW, Goldman S, Ilstrup DM, Kunselman AR, O'Neill PI: The pain drawing and Waddell’s nonorganic physical signs in chronic low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1993, 18 (13): 1717-1722. 10.1097/00007632-199310000-00001

Ransford AO, Cairns D, Mooney V: The pain drawing as an aid to the psychologic evaluation of patients with low back pain. Spine. 1976, 17: 127-134.

Hildebrandt J, Franz CE, Choroba-Mehnen B, Temme M: The use of pain drawings in screening for psychological involvement in complaints of low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1988, 13 (6): 681-685.

Parker H, Wood PLR, Main CJ: The use of the pain drawing as a screening measure to predict psychological distress in chronic low back pain. Spine. 1995, 20 (2): 23-243.

Carnes D, Ashby D, Underwood M: A systematic review of pain drawing literature: should pain drawings be used for psychologic screening?. Clin J Pain. 2006, 22 (5): 449-457. 10.1097/01.ajp.0000208245.41122.ac

Ohlund C, Eek C, Palmbald S, Areskoug B, Nachemson A: Quantified pain drawing in subacute low back pain. Validation in a nonselected outpatient industrial sample. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996, 21 (9): 1021-1030. discussion 1031,

Walker BF, Losco B, Clarke BR, Hebert J, French S, Stomski NJ: Outcomes of usual chiropractic, harm & efficacy, the ouch study: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2011, 12: 235- 10.1186/1745-6215-12-235

Walker BF, Hebert JJ, Stomski NJ, Losco B, French SD: Short term usual chiropractic care for spinal pain: a randomised controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). In press,

Walker B, Losco B, Clarke B, Hebert J, French S, Stomski N: Outcomes of usual chiropractic, harm & efficacy, the ouch study: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2011, 12 (1): 235- 10.1186/1745-6215-12-235

Katz J, Melzack R: Measurement of pain. Surg Clin North Am. 2010, 79: 231-252.

Feise RJ, Michael Menke J: Functional rating index: a new valid and reliable instrument to measure the magnitude of clinical change in spinal conditions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001, 26 (1): 78-86. discussion 87,

Sullivan M, Bishop S, Pivik J: The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995, 7: 524-532.

Ware J, Sherbourne C: The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992, 30: 473-483. 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002

Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, Somerville D, Main C: Fear Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain. 1993, 52: 157-168. 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90127-B

GIMP team: GIMP User Manual. 2009,http://docs.gimp.org/2.8/en/,

Schonberger T, Kasten P, Fechner K, Sudkamp NP, Pearce S, Niemeyer P: Novel software-based and validated evaluation method for objective quantification of bone regeneration in experimental bone defects. Z Orthop Unfall. 2010, 148 (1): 19-25.

Von Baeyer CL, Bergstrom KJ, Brodwin MG, Brodwin SK: Invalid use of pain drawings in psychological screening of back pain patients. Pain. 1983, 16 (1): 103-107. 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90089-1

Schwartz DP, DeGood DE: Global appropriateness of pain drawings: blind ratings predict patterns of psychological distress and litigation status. Pain. 1984, 19 (4): 383-388. 10.1016/0304-3959(84)90084-8

McNeill TW, Sinkora G, Leavitt F: Psychologic classification of low-back pain patients: a prognostic tool. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1986, 11 (9): 955-959. 10.1097/00007632-198611000-00018

Almay BG: Clinical characteristics of patients with idiopathic pain syndromes. Depressive symptomatology and patient pain drawings. Pain. 1987, 29 (3): 335-346. 10.1016/0304-3959(87)90048-0

Lindal E, Uden A: Cognitive differentiation, back pain, and psychogenic pain drawings. Percept Mot Skills. 1988, 67 (3): 835-845. 10.2466/pms.1988.67.3.835

Greenough CG, Fraser RD: Comparison of eight psychometric instruments in unselected patients with back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1991, 16 (9): 1068-1074. 10.1097/00007632-199109000-00010

Sikorski JM, Stampfer HG, Cole RM, Wheatley AE: Psychological aspects of chronic low back pain. Aust N Z J Surg. 1996, 66 (5): 294-297. 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1996.tb01189.x

Bessette L, Keller RB, Lew RA, Simmons BP, Fossel AH, Mooney N, Katz JN: Prognostic value of a hand symptom diagram in surgery for carpal tunnel syndrome. J Rheumatol. 1997, 24 (4): 726-734.

Hagg O, Fritzell P, Hedlund R, Moller H, Ekselius L, Nordwall A, Swedish Lumbar Spine S: Pain-drawing does not predict the outcome of fusion surgery for chronic low-back pain: a report from the Swedish Lumbar Spine Study. Eur Spine J. 2003, 12 (1): 2-11.

Rankine JJ, Fortune DG, Hutchinson CE, Hughes DG, Main CJ: Pain drawings in the assessment of nerve root compression: a comparative study with lumbar spine magnetic resonance imaging. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998, 23 (15): 1668-1676. 10.1097/00007632-199808010-00011

Dahl B, Gehrchen PM, Kiaer T, Blyme P, Tondevold E, Bendix T: Nonorganic pain drawings are associated with low psychological scores on the preoperative SF-36 questionnaire in patients with chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2001, 10 (3): 211-214. 10.1007/s005860100266

Hill JC, Dunn KM, Lewis M, Mullis R, Main CJ, Foster NE, Hay EM: A primary care back pain screening tool: identifying patient subgroups for initial treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 59 (5): 632-641. 10.1002/art.23563

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Peter Bryner in part funding this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

BW and NS are on the editorial team of Chiropractic and Manual Therapies but had no involvement in the editorial process of this manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

BW and NS contributed to the conception and design of the study. BW, NS and CL assisted with acquisition of data. All authors contributed to analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript, and have given final approval of the version to be published.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Walker, B.F., Losco, C.D., Armson, A. et al. The association between pain diagram area, fear-avoidance beliefs, and pain catastrophising. Chiropr Man Therap 22, 5 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/2045-709X-22-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2045-709X-22-5