Abstract

Background

The most common form of facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) is caused by a genetic contraction of the polymorphic D4Z4 macrosatellite repeat array in the subtelomeric region of chromosome 4q. In some studies, genes centromeric to the D4Z4 repeat array have been reported to be over-expressed in FSHD, including FRG1 and FRG2, presumably due to decreased long-distance repression by the shorter array through a mechanism similar to position-effect variegation. Differential regulation of FRG1 in FSHD has never been unequivocally proven, however, FRG2 has been reproducibly shown to be induced in primary FSHD-derived muscle cells when differentiated in vitro. The molecular function of FRG2 and a possible contribution to FSHD pathology remain unclear. Recent evidence has identified the mis-expression of DUX4, located within the D4Z4 repeat unit, in skeletal muscle as the cause of FSHD. DUX4 is a double homeobox transcription factor that has been shown to be toxic when expressed in muscle cells.

Methods

We used a combination of expression analysis by qRT/PCR and RNA sequencing to determine the transcriptional activation of FRG2 and DUX4. We examined this in both differentiating control and FSHD derived muscle cell cultures or DUX4 transduced control cell lines. Next, we used ChIP-seq analysis and luciferase reporter assays to determine the potential DUX4 transactivation effect on the FRG2 promoter.

Results

We show that DUX4 directly activates the expression of FRG2. Increased expression of FRG2 was observed following expression of DUX4 in myoblasts and fibroblasts derived from control individuals. Moreover, we identified DUX4 binding sites at the FRG2 promoter by chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by deep sequencing and confirmed the direct regulation of DUX4 on the FRG2 promoter by luciferase reporter assays. Activation of luciferase was dependent on both DUX4 expression and the presence of the DUX4 DNA binding motifs in the FRG2 promoter.

Conclusion

We show that the FSHD-specific upregulation of FRG2 is a direct consequence of the activity of DUX4 protein rather than representing a regional de-repression secondary to fewer D4Z4 repeats.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD; OMIM 158900/158901) is one of the most common myopathies with a prevalence of 1 in 8,000 according to a recent report[1]. Individuals with FSHD typically suffer from progressive weakening and wasting of the facial and upper extremity muscles with considerable inter- and intra-familial variability in disease onset and progression[2]. The pathogenic mechanism of FSHD has been linked to the polymorphic D4Z4 macrosatellite repeat array, located on chromosome 4q35, of which each unit contains a copy of a retrogene encoding for the germline transcription factor double homeobox protein 4 (DUX4)[3–5]. DUX4 has been shown to regulate a set of germline, early development, and innate immune response related genes and leads to increased levels of apoptosis when expressed in muscle cells[6–8]. Over recent years, a combination of detailed genetic and functional analyses in FSHD families and muscle biopsies has established that sporadic expression of the DUX4 retrogene in skeletal muscle is a feature shared by all individuals suffering from FSHD[9, 10].

Genetically, at least two forms of FSHD can be recognized. The majority of affected individuals (FSHD1, >95%) are characterized by a contraction of the D4Z4 repeat array. In healthy individuals, the D4Z4 macrosatellite repeat array consists of 11 to 100 copies, whereas individuals with FSHD1 have at least one contracted allele of 1 to 10 repeat units[4, 5, 11]. A second group of FSHD individuals (FSHD2, <5%) do not show a contraction of the D4Z4 repeat array, however most often have mutations in the chromatin modifier structural maintenance of chromosomes hinge domain containing protein 1 (SMCHD1) on chromosome 18p[12]. Both groups share two important (epi-)genetic features: they carry an allele permissive for stable DUX4 transcription because of the presence of a polymorphic DUX4 polyadenylation signal (PAS) and they display epigenetic derepression of the D4Z4 repeat array in somatic tissue[9, 13]. More specifically, in muscle biopsies and muscle cell cultures DUX4 expression has been correlated with decreased levels of CpG methylation and repressive histone modifications together with increased levels of transcriptional permissive chromatin markers at D4Z4[10, 14–17]. The epigenetic changes at D4Z4 can be either attributed to repeat array contraction (FSHD1) or loss of SMCHD1 activity at D4Z4 (FSHD2)[2].

The time interval between the genetic association of FSHD to the D4Z4 macrosatellite repeat array and the identification of sporadic DUX4 activation as a unifying disease mechanism encompasses almost 20 years of research into different candidate genes for FSHD[4, 9]. In the absence of a conclusive disease mechanism, genes proximal to the D4Z4 repeat have been investigated as possible FSHD disease genes, postulating that their regulation is affected in FSHD through a position effect emanating from the D4Z4 repeat array[16–22]. Among those candidate genes were FSHD Region Gene 1 (FRG1) and FSHD Region Gene 2 (FRG2) (Figure 1A). FRG1 is located on chromosome 4 at 120 kb proximal to the D4Z4 repeat and encodes a protein involved in actin bundle organization and mRNA biogenesis and transport[23–26]. Its overexpression leads to a dystrophic phenotype in different animal models, probably by affecting actin bundling and splicing of transcripts encoding muscle effector proteins[27–30]. However, most studies have failed to demonstrate FRG1 upregulation in FSHD muscle[17, 19, 20, 31–40]. FRG2 is a gene at 37 kb distance from the repeat encoding a nuclear protein of unknown function[41]. The distal end of chromosome 4 that contains the D4Z4 macrosatellite repeat array has been duplicated to chromosome 10[42, 43]. Consequently, due to its close proximity to the D4Z4 repeat array, FRG2 is located on both chromosomes 4 and 10 (Figure 1A). Additionally, a complete copy of FRG2 has been identified on the short arm of chromosome 3. We and others have previously reported on FSHD-specific transcriptional upregulation of FRG2 from both the 4q and 10q copies upon in vitro myogenesis, however its overexpression did not lead to a dystrophic phenotype in a transgenic mouse model[17, 27, 31, 41].

FRG2 activation in FSHD derived differentiating myoblasts. (A) Schematic representation of the FSHD locus on chromosome 4q35. Rectangles indicate the different genes, arrows their transcriptional direction. Triangles represent D4Z4 repeat units and the single inverted repeat unit upstream of FRG2. Each unit contains the full DUX4 ORF, only the last repeat unit produces a stable transcript in FSHD patients. The dashed line indicates the duplicated region present on chromosome 10q26. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of mean FRG2 expression levels in control (C), FSHD1 (F1) and FSHD2 (F2) derived proliferating myoblasts (MB) and differentiating myotubes (MT) shows the significant activation of FRG2 during differentiation only in F1 and F2 derived cells. Relative expression was determined using GAPDH and GUSB as reference genes. Sample numbers are indicated and error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Asterisks indicate significant differences based on a one-way ANOVA (P = 0.0014), followed by pairwise comparison using Bonferroni correction, NS = non-significant. (C) Genomic snapshot (location indicated at the bottom) of RNA sequencing data of two control, two FSHD1 and two FSHD2 derived proliferating myoblasts (MB) and differentiating myotubes (MT) confirms the full length expression of FRG2 in differentiating myotubes originating from FSHD individuals.

Until the discovery that mis-expression of DUX4 is shared by all FSHD individuals, these observations led to a disease model in which the contraction of the D4Z4 repeat array would create a position effect on proximal genes, thereby leading to their transcriptional activation. Such a mechanism cannot explain the activation of the 10q copy of FRG2, as this would require a trans-effect of the contracted repeat array. Although the D4Z4 copies on 4q and 10q have been shown to interact in interphase nuclei[44], this seems unlikely as 3D FISH approaches have revealed that the 4q D4Z4 repeat localizes to the nuclear periphery, whereas the 10q subtelomere does not[45]. More recently, it was shown that the expression of FRG2 in FSHD cells was influenced by telomere length through telomere position effects[46], leading to the conclusion that DUX4 and FRG2 were independently regulated by telomere-length. In the current study we provide evidence that the activation of FRG2 is a direct consequence of DUX4 protein activity, providing an experimentally supported cause for its specific expression in FSHD muscle and reconfirming DUX4 as the FSHD disease gene.

Methods

Cell culture

Human primary myoblast cell lines were obtained from the University of Rochester biorepository (http://www.urmc.rochester.edu/fields-center/) and were expanded and maintained in DMEM/F-10 (#31550 Gibco/Life Technologies, Bleiswijk, The Netherlands) supplemented with 20% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FCS #10270 Gibco), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (#15140 Gibco), 10 ng/mL rhFGF (#G5071 Promega, Leiden, The Netherlands) and 1 μM dexamethasone (#D2915 Sigma-Aldrich, Zwijndrecht, The Netherlands). Differentiation into myotubes was started at 80% confluency by serum starvation in DMEM/F-12 Glutamax (#31331, Gibco) supplemented with 2% KnockOut serum replacement formulation (#10828 Gibco) for 36 h. All samples and their characteristics used for our study are listed in Additional file1: Table S1. Rhabdomyosarcoma TE-671 were maintained in DMEM (#31966) supplemented with 10% FCS and 1% P/S (all Gibco).

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and qRT-PCR

Cells were harvested using Qiazol lysis reagent (#79306 Qiagen N.V., Venlo, The Netherlands) and RNA was subsequently isolated using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (#217004 Qiagen) including an on column DNase treatment according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A total of 2 μg RNA was used to synthesize poly-dT primed cDNA using the RevertAid H Minus First strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (#K1632 Thermo Fischer Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Relative FRG2 expression was quantified on the CFX96 system (Bio-Rad, Veenendaal, The Netherlands) using SYBR green master mix (Bio-Rad) with the following primers: FRG2_Fw: GGGAAAACTGCAGGAAAA, FRG2_Rv: CTGGACAGTTCCCTGCTGTGT. For relative quantification GUSB and GAPDH were used as reference genes and amplified with the following primers: GAPDH_Fw: GAGTCAACGGATTTGGTCGT, GAPDH_Rv: TTGATTTTGGAGGGATCTCG, GUSB_Fw: CCGAGTGAAGATCCCCTTTTTA, GUSB_Rv: CTCATTTGGAATTTTGCCGATT. All PCR reactions were carried out in duplicate and the data were analyzed using the Bio-Rad CFX manager version 3.0 (Bio-Rad).

Luciferase reporter assays

Genomic fragments containing the FRG2 promoter were amplified by regular PCR (primers pFRG2 _Fw: AGGCCTTACCTTGCCTTTGT; pFRG2_Rv: TCTTGCTGGTGGATGTTGAG) using cosmids 23D11 (chromosome 10) and cY34 (chromosome 4)[47, 48]. The obtained PCR fragments containing the promoter sites were digested with BglII and BclI and subcloned into the BglII digested pGL3 basic vector. Genomic locations of the cloned promotersites (UCSC hg19): chr4:190,948,283-190,949,163 and chr10:135,440,170-135,441,050. DUX4 binding sites were deleted by ligating PCR products obtained with internal primers (Fw_internal: ATCTGAGGGCCCTGATTCCTGAGGTAGC, Rv_internal: ATCTGAGGGCCCCATTTTTAAGGTAGGAAGG) combined with RV3 and GL2 primers annealing in the pGL3 backbone. Single binding sites were destroyed using site directed mutagenesis by PCR amplifying overlapping fragments with the following primers: Site 1Fw: CCTCAGGAATCAGGGGCTACATAGGGTAGCACTGACTCAACCT, Site 1Rv: AGGTTGAGTCAGTGCTACCCTATGTAGCCCCTGATTCCTGAGG, Site 2Fw: GGCTAATTAGGTTAGCACTGACTCACCCTATGCAATTCAATTTTATTGCATTTGATC, Site 2Rv: GATCAAATGCAATAAAATTGAATTGCATAGGGTGAGTCAGTGCTAACCTAATTAGCC, Site 3Fw: ACCTAATCAATTCAATTTTATTGCATTTGCACTAAGTATCTTCCCCATTTTTAAGGTAGGAAGG, Site 3Rv: CCTTCCTACCTTAAAAATGGGGAAGATACTTAGTGCAAATGCAATAAAATTGAATTGATTAGGT together with RV3 and GL2 primers. Insert sequences and correct orientation in the pGL3 vector were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Sixty thousand TE671 cells were seeded in standard 24 well tissue culture plates and co-transfected with 200 ng pCS2/pCS2-DUX4 and 200 ng of the indicated pGL3 constructs, using lipofectamine 2000 according to manufacturer’s instructions. Twenty-four hours after transfection cell lysates were harvested and luciferase activity was measured using the Promega luciferase assay kit, according to manufacturer’s instructions. Co-transfection with Renilla luciferase constructs for data normalization was omitted as we previously observed regulation of this construct by DUX4[49]. Transfections were carried out in triplicate, error bars indicate the SEM of three independent experiments.

RNA sequencing and ChIP sequencing

RNA sequencing and ChIP sequencing data were obtained and analyzed as described before[6, 36]. All datasets have previously been made publicly available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (accession numbers GSE56787, GSE33838). FRG2 expression in response to DUX4 overexpression is displayed for MB135, a control derived primary myoblast, and a control derived fibroblast. The genomic snapshots of the different datasets were generated using the IGV genome viewer version 2.3.32[50, 51].

Results

FRG2 expression is activated in differentiating FSHD derived muscle cells

We cultured a set of primary muscle cells derived from six controls, six FSHD1, and nine FSHD2 individuals and harvested RNA to analyze FRG2 transcript levels by quantitative realtime-PCR (qRT-PCR). We confirmed the significant FSHD-specific activation of FRG2 in differentiating myotubes (Figure 1B). In control samples, we observed a minor increase in FRG2 expression that was not statistically significant (Figure 1B). Analysis of previously published RNA-seq data from two additional controls and a subset of FSHD samples confirmed FRG2 activation (Figure 1C) and single base pair variations, known to differ between the three copies of FRG2[41], indicated transcripts were induced from FRG2 genes at all three genomic locations (Figure 2). Therefore, we conclude that increased transcription of FRG2 is not restricted to the copy on the 4q disease allele in FSHD1 and likely not caused by a cis effect of D4Z4 chromatin relaxation. The increase of FRG2 transcript levels coincided with activation of DUX4 transcription upon in vitro myogenesis in FSHD derived samples (Additional file2: Figure S1), as was reported before by us and others[36, 52, 53]. Altogether this confirms previously published data and highlights the robust transcriptional activation of all annotated copies of FRG2 in differentiating FSHD myotubes.

Sequence analysis of RNA sequencing reads reveals activation of FRG2 from all copies. Graphical representation of RNA-seq reads mapping to the FRG2C locus at chromosome 3p. Single nucleotide polymorphisms can be identified and are indicated by colored vertical lines (A = green, C = blue, G = orange, T = red). Different reads could thereby be assigned to the three different genomic copies of FRG2. Sequence analysis was based on the reference sequences obtained from the UCSC genome browser (build 19).

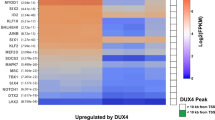

FRG2 activation is a direct consequence of DUX4 protein activity

As the activation of FRG2 in FSHD-derived myotubes follows the pattern of previously identified DUX4 target genes, we wondered if FRG2 is regulated by DUX4 directly. Indeed, we previously showed that FRG2 transcription was induced at least two-fold by expression array analysis in DUX4 over-expressing control myoblasts[6]. This robust increase in FRG2 transcription was confirmed by RNA-seq in both myoblasts and fibroblasts (Figure 3A) that were transduced with DUX4 expressing lentiviruses, ruling out a muscle specific effect of DUX4 on FRG2 expression. Direct targets of DUX4 were previously identified by overlaying expression data with chromatin immuno-precipitation (ChIP) sequencing data[6]. Following the same approach, we observed DUX4 binding at the promoter of FRG2 (Figure 3B). Sequence analysis of the 4q and 10q copies of the FRG2 promoter revealed that both chromosomes harbor three consensus binding sites for DUX4, which are not affected by minor sequence differences between the two loci (Figure 3C). To test the functional significance of these DUX4 binding sites, we designed luciferase reporter constructs harboring the FRG2 promoters of chromosomes 4 and 10. Co-transfection of these constructs with pCS2-DUX4 or the empty pCS2 backbone in TE-671 rhabdomyosarcoma cells confirmed that the activation of FRG2 is mediated by DUX4 protein expression (Figure 3D). To confirm that the activation of the luciferase reporter gene was indeed mediated by DUX4 binding, we generated a reporter construct with a micro-deletion of all three DUX4 binding sites in the FRG2 promoter derived from chromosome 10 (10Δ, Figure 3C). Upon co-transfection with the PCS2-DUX4 expression vector, the luciferase activation was completely ablated (Figure 3D). We identified three consecutive DUX4 binding sites in the FRG2 promoter, of which sites one and three contain a single base pair variation in the core sequence identified previously[6]. To dissect which sites were responsible for DUX4 dependent FRG2 activation, we designed three additional constructs, in which one of the three sites was destroyed by site directed mutagenesis (Figure 3C). Upon transfection of these constructs we observed that the activation of FRG2 by DUX4 is mediated primarily through the two binding sites furthest from the FRG2 transcriptional start site (TSS), as luciferase activity in response to DUX4 expression was no longer significantly induced. While destruction of the first binding site resulted in a complete absence of luciferase activation, the effect of DUX4 is still moderate, but non-significant, if site two is mutated (Figure 3D). Destroying the third binding site did not affect the DUX4 mediated activation of the FRG2 promoter (Figure 3D). Altogether, our data show that DUX4 binding at the FRG2 promoter is underlying the transcriptional activation of FRG2 in FSHD derived myogenic cultures.

FRG2 is activated as a consequence of DUX4 protein activity at its promoter. (A) Genomic snapshot (location indicated at the bottom) of mapped RNA-seq reads at the chromosome 4q FRG2 locus. Overexpression of DUX4 results in the activation of FRG2 in myoblasts and fibroblasts, GFP overexpression was used as a control. (B) Graphical representation of DUX4 binding at the 4q FRG2 promoter (genomic snapshot location indicated at the bottom) as revealed by ChIP-seq analysis (data obtained in myoblasts). (C) Genomic fragments obtained from chromosomes 4 and 10 were cloned upstream of the luciferase gene. Polymorphisms distinguishing both copies are indicated (Variants 1-3) and the three identified DUX4 binding sites are displayed, with nucleotides matching the previously identified core DUX4 binding sequence underlined. All numbers show the relative distance to the TSS of FRG2, in the 10mut1-3 constructs the number indicates the first displayed nucleotide. The 10Δ construct lacks all three DUX4 binding sites, whereas in 10mut1-3 the red nucleotides were mutated to the nucleotides indicated below them, thereby destroying the individual DUX4 binding sites. (D) DUX4 activates the FRG2 promoter in a luciferase reporter assay. Both the 4q and 10q copy of the FRG2 promoter are activated by DUX4. The 10q copy lacking the DUX4 binding sites (10Δ) was not activated by DUX4. Destruction of the three individual binding sites revealed that sites 1 and 2 are mediating the DUX4 dependent activation of FRG2. Counts per second (CPS) are a direct measure of luciferase activity, error bars indicate the SEM of three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate significant differences based on a one-way ANOVA (P <0.0001), followed by pairwise comparison using Bonferroni correction. NS = non-significant.

Discussion

Ever since the D4Z4 macrosatellite repeat array was genetically associated with FSHD, great effort has been put into identifying the underlying disease mechanism. The initial lack of evidence for active transcription of DUX4, encoded in each D4Z4 repeat unit, shifted the focus to genes immediately centromeric to the array, like FRG1 and FRG2. Although FRG1 overexpression in mice leads to a dystrophic phenotype, its deregulation in muscles of FSHD patients has not been consistently demonstrated[19, 27, 28, 31–34, 36–40]. In contrast, upregulation of FRG2 was consistently reported in FSHD-derived differentiating muscle cells; however the mechanism of FSHD-specific upregulation of FRG2 had not been conclusively established[17, 31, 41].

Activation of FRG2 in FSHD cells was previously attributed to de-repression through a position effect mechanism secondary to the contraction of the D4Z4 repeat array[17, 41]. Moreover, it was shown that KLF15 regulates both FRG2 expression and the activity of a putative enhancer in within D4Z4, thereby possibly facilitating a cis effect of the D4Z4 repeat array on the proximal FRG2 locus[54]. This model was challenged by showing that CpG methylation levels at a single CpG site centromeric to D4Z4 are unaffected in FSHD[13], indicating that DNA methylation was not broadly altered in the region centromeric to the D4Z4 repeat array in FSHD cells. The recent establishment of a unifying disease mechanism for FSHD, that primarily centers around DUX4, further challenges a position effect model that involves the deregulation of genes proximal to D4Z4 as a consequence of D4Z4 repeat array contraction. In line with this notion, we now show that FRG2 is a direct target gene of DUX4, providing a direct explanation for its upregulation in FSHD muscle.

As sporadic DUX4 activation is induced during in vitro muscle cell differentiation, the expression profile of FRG2 fits that of previously reported DUX4 target genes. It is interesting to note that we observed increased, though non significant, FRG2 expression in control derived differentiating muscle cells, which might indicate a minimal activation of the locus during in vitro myogenesis in control cells. DUX4 expression has been reported to occur in control derived myogenic cultures, albeit at much lower frequencies, and thus FRG2 may be activated as a consequence of that[55]. Alternatively, FRG2 expression may be sporadically induced through other mechanisms, exemplified by the reported regulation by KLF15[54].

DUX4 acts a potent transcriptional activator and induces expression of germline and early development genes through binding a specific homeobox sequence[6]. ChIP-seq analysis indeed identified DUX4 binding at the promoter of FRG2, which contains three consecutive DUX4 binding sites. Our experiments showed that the two sites furthest from the TSS of FRG2 are mediating the activation of FRG2 upon the expression of DUX4, confirming our earlier work showing that the probability of transcriptional activation by DUX4 increases with the number of consecutive DUX4 binding sites[56]. The FRG2 promoter sites at chromosomes 3, 4, and 10 are highly conserved, with identical sequences for the DUX4 sites on 4 and 10 and a limited number of single nucleotide differences between these and chromosome three that are predicted to preserve DUX4 binding, explaining the activation of all copies by DUX4[41]. In contrast to the complicated proposed mechanism of cis and trans effects of D4Z4 contraction at 4q[17, 41], the protein activity of DUX4 offers a simple and experimentally supported explanation for the activation of FRG2.

It was previously shown that FRG2 and DUX4 are regulated, at least in part, by telomere position effects[46]. Trans-activation of the FRG2 promoter was ruled out by transfecting promoter reporter constructs in immortalized FSHD derived myoblasts. However, the sporadic nature of DUX4 expression in these cells would seriously decrease the signal-to-noise ratio in this assay and a direct effect of DUX4 on FRG2 expression would likely have been missed. Although we cannot rule out a direct telomere position effect on FRG2 in this study, we suggest that the observed increase of FRG2 can be attributed to the increased DUX4 levels rather than to telomere position effects on FRG2. DUX4 itself may indeed be partially under control of telomere length and as such its target genes would follow a similar regulation.

As of yet, the functional consequence of FRG2 activation in FSHD remains elusive. FRG2 localizes to the nucleus[41], but its function has never been demonstrated and a possible role in FSHD disease progression is therefore unclear. The identification of FSHD individuals with proximally extended deletions, in which not only a large part of the D4Z4 repeat array, but also proximal sequences (including FRG2) were deleted, again suggests that a cis-acting effect on FRG2 is not necessary for FSHD pathology[57, 58]. However, since DUX4 activates other genomic copies of FRG2, it remains possible that this protein contributes to some aspect of the disease.

Conclusion

In this study we have firmly established that the long known activation of FRG2 in FSHD derived differentiating muscle cells is a direct consequence of DUX4 activity at its promoter. This provides further evidence for DUX4 as the central player in the FSHD disease mechanism and demonstrates that the higher expression of FRG2 in FSHD does not result from regional de-repression secondary to fewer D4Z4 repeats.

Abbreviations

- FSHD:

-

Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy

- FRG1:

-

FSHD Region Gene 1

- FRG2:

-

FSHD Region Gene 2

- DUX4:

-

Double homeobox 4

- SMCHD1:

-

Structural maintenance of chromosomes flexible hinge domain containing 1

- PAS:

-

Polyadenylation signal

- FISH:

-

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

- FBS:

-

Fetal bovine serum

- rhFGF:

-

Recombinant human fibroblast growth factor

- SEM:

-

Standard error of the mean

- ChIP-seq:

-

Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by deep sequencing

- qRT-PCR:

-

Quantative realtime polymerase chain reaction

- RNA-seq:

-

RNA sequencing

- KLF15:

-

Krüppel-like factor 15

- ORF:

-

Open reading frame

- MB/MT:

-

Myoblasts/myotubes

- TSS:

-

Transcriptional start site

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- CPS:

-

Counts per second.

References

Deenen JC, Arnts H, van der Maarel SM, Padberg GW, Verschuuren JJ, Bakker E, Weinreich SS, Verbeek AL, van Engelen BG: Population-based incidence and prevalence of facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. Neurol. 2014, 83: 1056-1059. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000797.

Tawil R, van der Maarel SM, Tapscott SJ: Facioscapulohumeral dystrophy: the path to consensus on pathophysiology. Skelet Muscle. 2014, 4: 12-10.1186/2044-5040-4-12.

Gabriels J, Beckers MC, Ding H, De Vriese A, Plaisance S, Van Der Maarel SM, Padberg GW, Frants RR, Hewitt JE, Collen D, Belayew A: Nucleotide sequence of the partially deleted D4Z4 locus in a patient with FSHD identifies a putative gene within each 3.3 kb element. Gene. 1999, 236: 25-32. 10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00267-X.

van Deutekom JC, Wijmenga C, van Tienhoven EA, Gruter AM, Hewitt JE, Padberg GW, van Ommen GJ, Hofker MH, Frants RR: FSHD associated DNA rearrangements are due to deletions of integral copies of a 3.2 kb tandemly repeated unit. Hum Mol Genet. 1993, 2: 2037-2042. 10.1093/hmg/2.12.2037.

Wijmenga C, Hewitt JE, Sandkuijl LA, Clark LN, Wright TJ, Dauwerse HG, Gruter AM, Hofker MH, Moerer P, Williamson R, van Ommen GJ, Padberg GW, Frants RR: Chromosome 4q DNA rearrangements associated with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1992, 2: 26-30. 10.1038/ng0992-26.

Geng LN, Yao Z, Snider L, Fong AP, Cech JN, Young JM, van der Maarel SM, Ruzzo WL, Gentleman RC, Tawil R, Tapscott SJ: DUX4 activates germline genes, retroelements, and immune mediators: implications for facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. Dev Cell. 2012, 22: 38-51. 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.11.013.

Kowaljow V, Marcowycz A, Ansseau E, Conde CB, Sauvage S, Matteotti C, Arias C, Corona ED, Nunez NG, Leo O, Wattiez R, Figlewicz D, Laoudj-Chenivesse D, Belayew A, Coppee F, Rosa AL: The DUX4 gene at the FSHD1A locus encodes a pro-apoptotic protein. Neuromuscul Disord. 2007, 17: 611-623. 10.1016/j.nmd.2007.04.002.

Wallace LM, Garwick SE, Mei W, Belayew A, Coppee F, Ladner KJ, Guttridge D, Yang J, Harper SQ: DUX4, a candidate gene for facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, causes p53-dependent myopathy in vivo. Ann Neurol. 2011, 69: 540-552. 10.1002/ana.22275.

Lemmers RJ, van der Vliet PJ, Klooster R, Sacconi S, Camano P, Dauwerse JG, Snider L, Straasheijm KR, van Ommen GJ, Padberg GW, Miller DG, Tapscott SJ, Tawil R, Frants RR, van der Maarel SM: A unifying genetic model for facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Science. 2010, 329: 1650-1653. 10.1126/science.1189044.

Snider L, Geng LN, Lemmers RJ, Kyba M, Ware CB, Nelson AM, Tawil R, Filippova GN, van der Maarel SM, Tapscott SJ, Miller DG: Facioscapulohumeral dystrophy: incomplete suppression of a retrotransposed gene. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6: e1001181-10.1371/journal.pgen.1001181.

Gilbert JR, Stajich JM, Wall S, Carter SC, Qiu H, Vance JM, Stewart CS, Speer MC, Pufky J, Yamaoka LH, Rozear M, Samson F, Fardeau M, Roses AD, Pericak-Vance MA: Evidence for heterogeneity in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD). Am J Hum Genet. 1993, 53: 401-408.

Lemmers RJ, Tawil R, Petek LM, Balog J, Block GJ, Santen GW, Amell AM, van der Vliet PJ, Almomani R, Straasheijm KR, Krom YD, Klooster R, Sun Y, den Dunnen JT, Helmer Q, Donlin-Smith CM, Padberg GW, van Engelen BG, de Greef JC, Aartsma-Rus AM, Frants RR, De VM, Desnuelle C, Sacconi S, Filippova GN, Bakker B, Bamshad MJ, Tapscott SJ, Miller DG, Van Der Maarel SM: Digenic inheritance of an SMCHD1 mutation and an FSHD-permissive D4Z4 allele causes facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy type 2. Nat Genet. 2012, 44: 1370-1374. 10.1038/ng.2454.

de Greef JC, Lemmers RJ, van Engelen BG, Sacconi S, Venance SL, Frants RR, Tawil R, van der Maarel SM: Common epigenetic changes of D4Z4 in contraction-dependent and contraction-independent FSHD. Hum Mutat. 2009, 30: 1449-1459. 10.1002/humu.21091.

Balog J, Thijssen PE, de Greef JC, Shah B, van Engelen BG, Yokomori K, Tapscott SJ, Tawil R, van der Maarel SM: Correlation analysis of clinical parameters with epigenetic modifications in the DUX4 promoter in FSHD. Epigenetics. 2012, 7: 579-584. 10.4161/epi.20001.

Zeng W, de Greef JC, Chien R, Kong X, Gregson HC, Winokur ST, Pyle A, Robertson KD, Schmiesing JA, Ball RJ, Donovan P, van der Maarel SM, Yokomori K: Specific loss of histone H3 lysine 9 trimethylation and HP1g/cohesin binding at D4Z4 repeats in facioscapulohumeral dystrophy (FSHD). PLoS Genet. 2009, 7: e1000559-

Cabianca DS, Casa V, Bodega B, Xynos A, Ginelli E, Tanaka Y, Gabellini D: A long ncRNA links copy number variation to a polycomb/trithorax epigenetic switch in FSHD muscular dystrophy. Cell. 2012, 149: 819-831. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.035.

Gabellini D, Green M, Tupler R: Inappropriate gene activation in FSHD. A repressor complex binds a chromosomal repeat deleted in dystrophic muscle. Cell. 2002, 110: 339-248. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00826-7.

Winokur ST, Bengtsson U, Feddersen J, Mathews KD, Weiffenbach B, Bailey H, Markovich RP, Murray JC, Wasmuth JJ, Altherr MR, Schutte BR: The DNA rearrangement associated with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy involves a heterochromatin-associated repetitive element: implications for a role of chromatin structure in the pathogenesis of the disease. Chromosome Res. 1994, 2: 225-234. 10.1007/BF01553323.

Jiang G, Yang F, van Overveld PG, Vedanarayanan V, Van Der MS, Ehrlich M: Testing the position-effect variegation hypothesis for facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy by analysis of histone modification and gene expression in subtelomeric 4q. Hum Mol Genet. 2003, 12: 2909-2921. 10.1093/hmg/ddg323.

Bodega B, Ramirez GD, Grasser F, Cheli S, Brunelli S, Mora M, Meneveri R, Marozzi A, Mueller S, Battaglioli E, Ginelli E: Remodeling of the chromatin structure of the facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) locus and upregulation of FSHD-related gene 1 (FRG1) expression during human myogenic differentiation. BMC Biol. 2009, 7: 41-10.1186/1741-7007-7-41.

Petrov A, Pirozhkova I, Carnac G, Laoudj D, Lipinski M, Vassetzky YS: Chromatin loop domain organization within the 4q35 locus in facioscapulohumeral dystrophy patients versus normal human myoblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006, 103: 6982-6987. 10.1073/pnas.0511235103.

Petrov A, Allinne J, Pirozhkova I, Laoudj D, Lipinski M, Vassetzky YS: A nuclear matrix attachment site in the 4q35 locus has an enhancer-blocking activity in vivo: implications for the facio-scapulo-humeral dystrophy. Genome Res. 2007, 18: 39-45. 10.1101/gr.6620908.

van Deutekom JCT, Lemmers RJLF, Grewal PK, van Geel M, Romberg S, Dauwerse HG, Wright TJ, Padberg GW, Hofker MH, Hewitt JE, Frants RR: Identification of the first gene (FRG1) from the FSHD region on human chromosome 4q35. Hum Mol Genet. 1996, 5: 581-590. 10.1093/hmg/5.5.581.

Liu Q, Jones TI, Tang VW, Brieher WM, Jones PL: Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy region gene-1 (FRG-1) is an actin-bundling protein associated with muscle-attachment sites. J Cell Sci. 2010, 123: 1116-1123. 10.1242/jcs.058958.

Sun CY, Van KS, Long SW, Straasheijm K, Klooster R, Jones TI, Bellini M, Levesque L, Brieher WM, Van Der Maarel SM, Jones PL: Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy region gene 1 is a dynamic RNA-associated and actin-bundling protein. J Mol Biol. 2011, 411: 397-416. 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.06.014.

Hanel ML, Sun CY, Jones TI, Long SW, Zanotti S, Milner D, Jones PL: Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) region gene 1 (FRG1) is a dynamic nuclear and sarcomeric protein. Differentiation. 2011, 81: 107-118. 10.1016/j.diff.2010.09.185.

Gabellini D, D'Antona G, Moggio M, Prelle A, Zecca C, Adami R, Angeletti B, Ciscato P, Pellegrino MA, Bottinelli R, Green MR, Tupler R: Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy in mice overexpressing FRG1. Nature. 2006, 439: 973-977.

Hanel ML, Wuebbles RD, Jones PL: Muscular dystrophy candidate gene FRG1 is critical for muscle development. Dev Dyn. 2009, 238: 1502-1512. 10.1002/dvdy.21830.

Sancisi V, Germinario E, Esposito A, Morini E, Peron S, Moggio M, Tomelleri G, Danieli-Betto D, Tupler R: Altered Tnnt3 characterizes selective weakness of fast fibers in mice overexpressing FSHD region gene 1 (FRG1). Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2014, 306: R124-R137. 10.1152/ajpregu.00379.2013.

Pistoni M, Shiue L, Cline MS, Bortolanza S, Neguembor MV, Xynos A, Ares M, Gabellini D: Rbfox1 downregulation and altered calpain 3 splicing by FRG1 in a mouse model of Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD). PLoS Genet. 2013, 9: e1003186-10.1371/journal.pgen.1003186.

Klooster R, Straasheijm K, Shah B, Sowden J, Frants R, Thornton C, Tawil R, van der Maarel S: Comprehensive expression analysis of FSHD candidate genes at the mRNA and protein level. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009, 17: 1615-1624. 10.1038/ejhg.2009.62.

Osborne RJ, Welle S, Venance SL, Thornton CA, Tawil R: Expression profile of FSHD supports a link between retinal vasculopathy and muscular dystrophy. Neurol. 2007, 68: 569-577. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000251269.31442.d9.

Cheli S, Francois S, Bodega B, Ferrari F, Tenedini E, Roncaglia E, Ferrari S, Ginelli E, Meneveri R: Expression profiling of FSHD-1 and FSHD-2 cells during myogenic differentiation evidences common and distinctive gene dysregulation patterns. PLoS One. 2011, 6: e20966-10.1371/journal.pone.0020966.

Winokur ST, Chen YW, Masny PS, Martin JH, Ehmsen JT, Tapscott SJ, van der Maarel SM, Hayashi Y, Flanigan KM: Expression profiling of FSHD muscle supports a defect in specific stages of myogenic differentiation. Hum Mol Genet. 2003, 12: 2895-2907. 10.1093/hmg/ddg327.

Masny PS, Chan OY, de Greef JC, Bengtsson U, Ehrlich M, Tawil R, Lock LF, Hewitt JE, Stocksdale J, Martin JH, van der Maarel SM, Winokur ST: Analysis of allele-specific RNA transcription in FSHD by RNA-DNA FISH in single myonuclei. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010, 18: 448-456. 10.1038/ejhg.2009.183.

Yao Z, Snider L, Balog J, Lemmers RJ, Van Der Maarel SM, Tawil R, Tapscott SJ: DUX4-induced gene expression is the major molecular signature in FSHD skeletal muscle. Hum Mol Genet. 2014, 23: 5342-5352. 10.1093/hmg/ddu251.

Xu X, Tsumagari K, Sowden J, Tawil R, Boyle AP, Song L, Furey TS, Crawford GE, Ehrlich M: DNaseI hypersensitivity at gene-poor, FSH dystrophy-linked 4q35.2. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37: 7381-7393. 10.1093/nar/gkp833.

Arashiro P, Eisenberg I, Kho AT, Cerqueira AM, Canovas M, Silva HC, Pavanello RC, Verjovski-Almeida S, Kunkel LM, Zatz M: Transcriptional regulation differs in affected facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy patients compared to asymptomatic related carriers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009, 106: 6220-6225. 10.1073/pnas.0901573106.

Celegato B, Capitanio D, Pescatori M, Romualdi C, Pacchioni B, Cagnin S, Vigano A, Colantoni L, Begum S, Ricci E, Wait R, Lanfranchi G, Gelfi C: Parallel protein and transcript profiles of FSHD patient muscles correlate to the D4Z4 arrangement and reveal a common impairment of slow to fast fibre differentiation and a general deregulation of MyoD-dependent genes. Proteomics. 2006, 6: 5303-5321. 10.1002/pmic.200600056.

Tsumagari K, Chang SC, Lacey M, Baribault C, Chittur SV, Sowden J, Tawil R, Crawford GE, Ehrlich M: Gene expression during normal and FSHD myogenesis. BMC Med Genomics. 2011, 4: 67-10.1186/1755-8794-4-67.

Rijkers T, Deidda G, van Koningsbruggen S, van Geel M, Lemmers RJ, van Deutekom JC, Figlewicz D, Hewitt JE, Padberg GW, Frants RR, van der Maarel SM: FRG2, an FSHD candidate gene, is transcriptionally upregulated in differentiating primary myoblast cultures of FSHD patients. J Med Genet. 2004, 41: 826-836. 10.1136/jmg.2004.019364.

Bakker E, Wijmenga C, Vossen RH, Padberg GW, Hewitt J, van der Wielen M, Rasmussen K, Frants RR: The FSHD-linked locus D4F104S1 (p13E-11) on 4q35 has a homologue on 10qter. Muscle Nerve. 1995, 2: 39-44.

Deidda G, Cacurri S, Grisanti P, Vigneti E, Piazzo N, Felicetti L: Physical mapping evidence for a duplicated region on chromosome 10qter showing high homology with the Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy locus on chromosome 4qter. Eur J Hum Genet. 1995, 3: 155-167.

Stout K, van der Maarel S, Frants RR, Padberg GW, Ropers H-H, Haaf T: Somatic pairing between subtelomeric regions: implications for human genetic disease?. Chrom Res. 1999, 7: 323-329. 10.1023/A:1009287111661.

Masny PS, Bengtsson U, Chung SA, Martin JH, van Engelen B, van der Maarel SM, Winokur ST: Localization of 4q35.2 to the nuclear periphery: is FSHD a nuclear envelope disease?. Hum Mol Genet. 2004, 13: 1857-1871. 10.1093/hmg/ddh205.

Stadler G, Rahimov F, King OD, Chen JC, Robin JD, Wagner KR, Shay JW, Emerson CP, Wright WE: Telomere position effect regulates DUX4 in human facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013, 20: 671-678. 10.1038/nsmb.2571.

Van Deutekom JCT, Hofker MH, Romberg SA, Van Geel M, Rommens J, Wright TJ, Hewitt JE, Padberg GW, Wijmenga C, Frants RR: Search for the FSHD gene using cDNA selection in a region spanning 100 kb on chromosome 4q35. Muscle Nerve Suppl. 1995, 2: S19-S26.

van Geel M, Dickson MC, Beck AF, Bolland DJ, Frants RR, van der Maarel SM, de Jong PJ, Hewitt JE: Genomic analysis of human chromosome 10q and 4q telomeres suggests a common origin. Genomics. 2002, 79: 210-217. 10.1006/geno.2002.6690.

Krom YD, Thijssen PE, Young JM, Den HB, Balog J, Yao Z, Maves L, Snider L, Knopp P, Zammit PS, Rijkers T, Van Engelen BG, Padberg GW, Frants RR, Tawil R, Tapscott SJ, Van Der Maarel SM: Intrinsic epigenetic regulation of the D4Z4 macrosatellite repeat in a transgenic mouse model for FSHD. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9: e1003415-10.1371/journal.pgen.1003415.

Thorvaldsdottir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP: Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief Bioinform. 2013, 14: 178-192. 10.1093/bib/bbs017.

Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, Mesirov JP: Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol. 2011, 29: 24-26. 10.1038/nbt.1754.

Block GJ, Narayanan D, Amell AM, Petek LM, Davidson KC, Bird TD, Tawil R, Moon RT, Miller DG: Wnt/beta-catenin signaling suppresses DUX4 expression and prevents apoptosis of FSHD muscle cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2013, 22: 4661-4672. 10.1093/hmg/ddt314.

Krom YD, Dumonceaux J, Mamchaoui K, Den HB, Mariot V, Negroni E, Geng LN, Martin N, Tawil R, Tapscott SJ, Van Engelen BG, Mouly V, Butler Browne GS, Van Der Maarel SM: Generation of isogenic D4Z4 contracted and noncontracted immortal muscle cell clones from a mosaic patient: a cellular model for FSHD. Am J Pathol. 2012, 181: 1387-1401. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.07.007.

Dmitriev P, Petrov A, Ansseau E, Stankevicins L, Charron S, Kim E, Bos TJ, Robert T, Turki A, Coppee F, Belayew A, Lazar V, Carnac G, Laoudj D, Lipinski M, Vassetzky YS: The Kruppel-like factor 15 as a molecular link between myogenic factors and a chromosome 4q transcriptional enhancer implicated in facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. J Biol Chem. 2011, 286: 44620-44631. 10.1074/jbc.M111.254052.

Jones TI, Chen JC, Rahimov F, Homma S, Arashiro P, Beermann ML, King OD, Miller JB, Kunkel LM, Emerson CP, Wagner KR, Jones PL: Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy family studies of DUX4 expression: evidence for disease modifiers and a quantitative model of pathogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2012, 21: 4419-4430. 10.1093/hmg/dds284.

Young JM, Whiddon JL, Yao Z, Kasinathan B, Snider L, Geng LN, Balog J, Tawil R, van der Maarel SM, Tapscott SJ: DUX4 binding to retroelements creates promoters that are active in FSHD muscle and testis. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9: e1003947-10.1371/journal.pgen.1003947.

Deak KL, Lemmers RJ, Stajich JM, Klooster R, Tawil R, Frants RR, Speer MC, van der Maarel SM, Gilbert JR: Genotype-phenotype study in an FSHD family with a proximal deletion encompassing p13E-11 and D4Z4. Neurology. 2007, 68: 578-582. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000254991.21818.f3.

Lemmers RJLF, van der Maarel SM, van Deutekom JCT, van der Wielen MJR, Deidda G, Dauwerse HG, Hewitt J, Hofker M, Bakker E, Padberg GW, Frants RR: Inter- and intrachromosomal subtelomeric rearrangements on 4q35: implications for facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) aetiology and diagnosis. Hum Mol Genet. 1998, 7: 1207-1214. 10.1093/hmg/7.8.1207.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all the patients and their families who participated in this study. This study was financially supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) P01NS069539, and National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) R01AR045203), the Geraldi Norton and Eklund family foundation, the FSH Society, Spieren voor Spieren, and The Friends of FSH Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PT designed, performed, and analyzed experiments, analyzed genome-wide data, and drafted and finalized the manuscript; JB designed, performed, and analyzed experiments, and revised the manuscript; ZY designed, performed, and analyzed genome-wide experiments/data, and revised the manuscript; TPP designed, performed, and analyzed experiments; RT provided key biological material and revised the manuscript; SJT designed and analyzed experiments, and drafted and revised the manuscript; SVDM designed and analyzed experiments, and drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

13395_2014_109_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Additional file 1: Table S1: Characteristics of samples used for qRT-PCR and RNA-seq analysis. Length in kb and haplotype of both 4q D4Z4 alleles are indicated. (PDF 41 KB)

13395_2014_109_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Additional file 2: Figure S1: RNA-sequencing reads mapping to D4Z4 showed DUX4 activation in differentiating FSHD derived muscle cells. Graphical representation of RNA-seq reads mapping to the 4q D4Z4 repeat, indicative for DUX4 expression, showed FSHD specific activation of DUX4 upon differentiation. Sequenced transcripts were mapped to DUX4 ORFs, encoded within each D4Z4 repeat, which are annotated with gene symbols DUX2, DUX4, DUX4L4, and DUX4L5. MB = myoblasts, MT = myotubes; the genomic location of the snapshot is indicated at the bottom. (PDF 106 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Thijssen, P.E., Balog, J., Yao, Z. et al. DUX4 promotes transcription of FRG2 by directly activating its promoter in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Skeletal Muscle 4, 19 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/2044-5040-4-19

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2044-5040-4-19