Abstract

Background

In recent years, phylogeographic studies have produced detailed knowledge on the worldwide distribution of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) variants, linking specific clades of the mtDNA phylogeny with certain geographic areas. However, a multiplex genotyping system for the detection of the mtDNA haplogroups of major continental distribution that would be desirable for efficient DNA-based bio-geographic ancestry testing in various applications is still missing.

Results

Three multiplex genotyping assays, based on single-base primer extension technology, were developed targeting a total of 36 coding-region mtDNA variants that together differentiate 43 matrilineal haplo-/paragroups. These include the major diagnostic haplogroups for Africa, Western Eurasia, Eastern Eurasia and Native America. The assays show high sensitivity with respect to the amount of template DNA: successful amplification could still be obtained when using as little as 4 pg of genomic DNA and the technology is suitable for medium-throughput analyses.

Conclusions

We introduce an efficient and sensitive multiplex genotyping system for bio-geographic ancestry inference from mtDNA that provides resolution on the continental level. The method can be applied in forensics, to aid tracing unknown suspects, as well as in population studies, genealogy and personal ancestry testing. For more complete inferences of overall bio-geographic ancestry from DNA, the mtDNA system provided here can be combined with multiplex systems for suitable autosomal and, in the case of males, Y-chromosomal ancestry-sensitive DNA markers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Establishing the geographic region of a person's genetic origin - also called bio-geographic ancestry - is of forensic relevance when the short tandem repeat (STR) profile of trace DNA found at a crime scene does not match that of a suspect or does not yield any matches in a criminal DNA database because it may provide investigative leads to finding unknown persons [1]. Similarly, such information can be useful for locating antemortem samples or putative relatives of unidentified body remains, including disaster victim identification [2]. Furthermore, inferring geographic information from DNA data is important in population history studies [3, 4] and has gained attention in the growing field of personal ancestry testing [5, 6].

Several years of intensive research into the understanding of the geographic distribution of human genetic diversity present in the non-recombining mitochondrial genome and respective parts of the Y-chromosome (NRY), mostly for population history purposes, have produced an immense body of knowledge allowing us to pick specific mtDNA and NRY markers with restricted (sub)continental distributions [4, 7, 8]. MtDNA is especially useful for forensic application due to its high copy number (hundreds to thousands of copies per cell) and small size (16.6 kb), which allows the analysis of small amounts of degraded DNA often encountered in crime-scene situations [9]. Although mtDNA only reveals information about matrilineal ancestry, it can be seen as a first step toward a more comprehensive picture of personal ancestry when combined with suitable NRY and autosomal DNA evidence [10, 11]. Furthermore, investigating the geographic origin of mtDNA in comparison to that of the Y-chromosome in a population can also reveal insights into sex-biased aspects of human population history such as those caused by patri- or matrilocal residence patterns [12].

In human population genetics studies, the typical approach for mtDNA analysis consists of sequencing the first hypervariable segment (HVS1), sometimes in combination with HVS2, within the non-coding control region (see, for example [13, 14]), whereas in forensics it has nowadays become standard practice to sequence the entire control region [15]. Although haplogroup inference from HVS sequence data is possible for many mtDNA haplogroups, not all haplogroups present suitable diagnostic variants in HVS1 and/or HVS2 that allow an unequivocal assignment. In such cases, simple nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs; i.e. single-nucleotide polymorphisms as well as small insertions and deletions) from the coding region of mtDNA are required in order to establish the haplogroup status. Moreover, because SNP typing assays are usually more sensitive and consume less DNA than sequencing, in many cases it might be desirable to perform SNP genotyping alone (in the absence of HVS data) or prior to HVS sequencing [16, 17].

Several mtDNA SNP multiplex assays have already been developed focussing on particular geographic subregions (see, for example, [18]) or on the dissection of particular haplogroups (see, for example, [19]). However, what is missing so far is an mtDNA SNP multiplex system that includes the mtDNA haplogroups of major continental distribution. We describe a sensitive genotyping system based on single-base primer extension technology, consisting of three independent multiplex assays that together include 36 SNPs determining 43 mtDNA haplo-/paragroups that allow the inference of matrilineal bio-geographic ancestry at the level of continental resolution.

Results and discussion

Multiplexes and targeted haplogroups

MtDNA coding-region SNPs defining the major haplogroups that occur in Africa, Western Eurasia, Eastern Eurasia and Native America were carefully selected (Figure 1) and combined into three multiplex genotyping assays (Figures 2, 3, 4) each consisting of a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification step and a subsequent single-base primer extension step (Tables 1, 2, 3). The haplogroups detectable with Multiplex 1 and 2 are broadly similar to those typed by the Genographic Project [20] with some noticeable exceptions. Multiplex 1 (Figure 2) was designed to target haplogroups L0/L1, L2/L4/L6, L3, M, M1, C, D, N, N1, I, W, A, X and R. Due to the homoplasy of some of the selected markers in the worldwide mtDNA phylogeny [7], Multiplex 1 can additionally detect some (relatively rare) haplogroups that were not originally intended, namely L0k/L0d1a/L0d3, L5, X2a1, R11/B6 and B4a1. The hierarchical organization of the mitochondrial SNPs in Multiplex 1 ensures that all these haplogroups, intended and unintended, are well differentiable (Figure 2). Some haplogroups are only identified with Multiplex 1 on a broad level and, in those cases, additional genotyping with Multiplex 2 or 3 is needed to achieve further haplogroup resolution and final geographic inferences. Multiplex 2 (Figure 3) targets haplogroup R and haplogroups nested within R, namely R0, HV, HV0a (which includes V), H, R9 (which includes F), B, J, T, U, U6 and U8b (which includes K). A notable difference with the Genographic Project SNP panel [20] is that we included in our multiplexes haplogroups M1 and U6 which have a predominantly African distribution, probably due to back-migration events to Africa [21]. As such, Multiplex 1 and 2 together offer a convenient method for the classification of unknown mtDNAs into any of the major worldwide mtDNA haplogroups. However, they do not allow for the differentiation of the Native American subsets of otherwise Eastern Eurasian haplogroups A, B, C and D and Western Eurasian/African haplogroup X. Therefore, we designed a third assay, Multiplex 3 (Figure 4), which specifically aims at detecting the Native American haplogroups A2, B2, C1, C4c, D1, D4h3a and X2a, as well as Eskimo/Siberian haplogroups A2a, A2b, D2a and D3 and Eastern Eurasian haplogroup C1a [22]. Together, the three multiplexes include 36 different coding-region mtDNA SNPs (of which 34 are single-nucleotide transitions/transversions and two are small insertion/deletion polymorphisms). It should be noted that, despite the fact that haplogroups M1, C and D within macrohaplogroup M, haplogroups N1, A, W and X within macrohaplogroup N, and haplogroups R0, R9, B, JT and U within macrohaplogroup R, can be detected with the method, much of the Southern Asian, East/Southeast Asian and Oceanic variation within M, N and R remains unresolved (denoted as M*, N* and R*, respectively, in Figure 1). However, this is inevitable given the large number of independent haplogroups descending from M, N and R but it can be overcome by developing additional multiplex assays that specifically target the relevant subhaplogroups for those regions.

Overall phylogenetic scheme of targeted mtSNPs with geographic haplogroup classification. The combined use of the three multiplex assays allows any person's mtDNA to be classified into one of the colour-labelled haplogroups. Colours correspond to the geographic origin of the haplogroups as indicated. SNP position numbers are relative to the revised Cambridge Reference Sequence (rCRS). Deletion mutations are denoted by the suffix 'd'. Recurrent SNPs are underlined. The numbers 1, 2 or 3 in square brackets shown for each SNP refer to the respective multiplex assay in which the SNP is included. Note: haplogroups F, K and V are encompassed within R9, U8b and HV0a, respectively, as indicated because this does not follow logically from the nomenclature.

Marker phylogeny and haplogroup-defining genotypes of Multiplex 1. Recurrent SNPs are underlined. Boxed alleles indicate for each haplogroup those SNPs that are minimally required to define that haplogroup. If additional genotyping is required for more detailed haplogroup inference, the respective additional multiplex to be genotyped subsequently is noted.

Marker phylogeny and haplogroup-defining genotypes of Multiplex 2. Boxed alleles indicate for each haplogroup those SNPs that are minimally required to define that haplogroup. The allelic states of deletion polymorphism 8281-8289 are denoted as 'a' (ancestral) and 'd' (deletion), respectively. If additional genotyping is required for more detailed haplogroup inference, the respective additional multiplex to be genotyped subsequently is noted.

Design and optimization

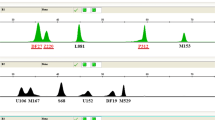

The successful dessign of a useful multiplex single-base extension assay requires careful consideration of the SNPs and their PCR amplification primers as well as extension primers, followed by extensive laboratory testing [23]. One criterion of SNP selection was the overall level of homoplasy of the marker in the entire mtDNA phylogeny [7]. For each haplogroup, one or several defining SNPs are available; in the latter case care was taken to select the more stable (phylogenetically less recurrent) SNP sites. Nevertheless, some of the selected SNPs do occur more than once in the phylogeny (underlined in Figure 1) as discussed above. Notably, Multiplex 1 contains two tri-allelic SNPs: nucleotide position (np) 3552 is either a T (ancestral state), an A (haplogroup C), or a C (haplogroup X2a1); and np 12950 is either an A (ancestral state), a C (haplogroup M1) or a G (haplogroups L5, R11 and B6). Primer design using Primer3Plus [24] considered small amplicon size and avoided numt amplification [25]. The compatibility of primers within the same multiplex was checked with AutoDimer [26], especially avoiding 3' end complementarities. Amplicon sizes were kept small, ranging from 80 to 237 bp with an average of 133 bp (Tables 1, 2, 3), in order to facilitate the amplification of (partially) degraded DNA typically encountered in forensic settings as well as in population history studies when using difficult source materials (for example, ancient DNA). All primers were first tested in singleplex before combining them in a multiplex. Primers that showed substantial artifacts were replaced by alternatively designed primers. In order to ensure electrophoretic separation of extension primer products, extension primers within the same multiplex were given different lengths by adding 5' non-homologous (poly)GACT tails (Tables 1, 2, 3). Peak heights in the electropherograms (Figures 5, 6) were balanced by adjusting primer concentrations in the PCR and extension reactions (Tables 1, 2, 3).

Electropherograms of Multiplex 1-3 for a European and an African individual, using varying amounts of initial DNA template. (A) European individual of haplogroup J; (B) African individual of haplogroup L3*(xM,N). The three multiplex assays were each performed on five different starting amounts of DNA template, ranging from 0.25 ng to 0.001 ng. Grey circles indicate marker dropouts that occur at the very low DNA concentration whereas grey arrows indicate cases where allele calling becomes difficult due to artefacts that come up at the low DNA concentrations.

Electropherograms of Multiplex 1-3 for a Native American and an East Asian individual, using varying amounts of initial DNA template. (A) Native American individual of haplogroup C1*(xC1a); (B) East Asian individual of haplogroup R9. The three multiplex assays were each performed on five different starting amounts of DNA template, ranging from 0.25 ng to 0.001 ng. Grey circles indicate marker dropouts that occur at the very low DNA concentration whereas grey arrows indicate cases where allele calling becomes difficult due to artefacts that come up at the low DNA concentrations.

Haplogroup distribution and inferring bio-geographic ancestry

The labels used to describe the geographic affiliations of the haplogroups (Figure 1) mostly correspond to one of four regions or continents of the world, namely Africa, Western Eurasia, Eastern Eurasia and Native America, consistent with the terminology used in human genetics and anthropology literature. With some haplogroups, however, only combined regions can be inferred, namely Western Eurasia/Africa, Western Eurasia/Southern Asia, Eastern Eurasia/Oceania, Native America/Eastern Eurasia and Eastern Eurasia/Southern Asia/Oceania (Figure 1). While these geographic designations are convenient descriptors of the 'center of gravity' of haplogroup occurrence, it is important to keep in mind that, instead of sharp genetic borders, there exist transition areas between continents. Populations from the Middle East, for example, carry a considerable portion of African mtDNA lineages [27]. Similarly, Northern Africa has a relatively large portion of Western Eurasian mtDNA lineages [28, 29]. In addition, the Central Asian mtDNA pool is composed of Western Eurasian, Eastern Eurasian and, to a lesser extent, also Southern Asian components [30, 31]

Furthermore, one should be aware that traditional distribution patterns of genetic variation, including mtDNA, may have been affected by (evolutionary recent) migration/admixture events, including as a result of colonialism, so that some populations carry portions of ancestry from multiple geographic regions. The most prominent case is, perhaps, the American continent where, due to colonization by Europeans which started around the beginning of the 16th century and the subsequent European introduction of African slaves, the current population carries a mixture of Native American, Western Eurasian and African mtDNA lineages, in varying proportions depending on the subpopulation [10, 11, 14, 32, 33]. Other well-known cases include Madagascar (African and Eastern Eurasian lineages) [13], and coastal/island parts of Near Oceania, as well as all of Remote Oceania (Oceanic and Eastern Eurasian lineages) [34]. In addition, groups of more or less recent immigrants often carry a mixture of 'native' lineages and lineages typical from the area to which they moved. For example, Polish Roma, having an ultimate origin in India, harbour both Southern Asian and Western Eurasian mtDNA variants [35]. Finally, rare cases have been reported where European individuals carried African mtDNA haplogroups without being aware of any African ancestry [36]. Therefore, for any bio-geographic ancestry prediction purposes, mtDNA evidence should be interpreted in the context of the relevant local demographic history. Also, because mtDNA only reflects the matrilineal portion of a person's genetic ancestry, ideally the markers should be combined with evidence obtained from autosomal and/or (when dealing with male DNA) Y-chromosome markers, to obtain a more accurate picture of a person's overall ancestry.

Sensitivity testing

In order to establish the sensitivity of our multiplex assays we performed tests with different starting amounts of genomic DNA, ranging from 25 ng to 1 pg of template DNA, for four individuals originating from different continents and with respective diagnostic haplogroups: a European with haplogroup J; an African with L3*(xM,N); a Native American with C1*(xC1a); and an East Asian with R9 (Figures 5, 6). This enabled us to monitor the behaviour of the different SNP alleles with decreasing amounts of template DNA. Overall, we observed high sensitivity and basically full profiles could be obtained with all three multiplexes for all four individuals with as little as 4 pg of DNA template (with the only exception of 13368 in Multiplex 2 that sometimes caused difficulties in allele calling with 4 pg and lower). Marker dropouts for some SNPs in all the individuals and all three multiplexes (except for Multiplex 1 in the European and the African sample and with Multiplex 3 in the European) started to occur only at the 1 pg level, as well as allele-calling difficulties for some other SNPs in all three multiplexes (Figures 5, 6). The achieved sensitivity is similar to that of two previously published mtDNA multiplex assays [18, 37] but, presumably, higher than that of many other published mtDNA multiplexes which typically require 1-10 ng DNA (for example [19, 38–40]; although many such studies do not provide details on sensitivity). Furthermore, the achieved sensitivity of our assays is significantly higher than that of commercially available STR multiplexes [41–43], which can be expected due to the higher relative abundance of mtDNA as compared to nuclear DNA. When working with ancient DNA or forensic trace DNA, it might be useful to quantify the amount of human DNA prior to genotyping because, in such situations, human DNA often represents only a fraction of total DNA due to the presence of non-human (for example, bacterial, fungal, or others) DNA.

Illustration of the method application

In order to illustrate the reliability of our method in inferring bio-geographic ancestry from mtDNA, we compared in worldwide individuals, their haplogroup status as determined from full mtDNA sequence data and their population affiliation known from the sampling region, with the haplogroup and corresponding geographic information obtainable from our multiplex SNP assays (Table 4). The data used for this purpose consisted of 75 samples from the Centre d'Etude du Polymorphisme Humain-Human Genome Diversity Project (CEPH-HGDP) panel [44] for which entire mitochondrial genome sequences are available [45]. From the full mtDNA sequences we extracted the alleles of those SNP sites that are included in our assays and used the resulting genotypes to infer haplogroups and respective geographic regions of matrilineal origin. In all cases, the haplogroups inferable by our assays were consistent with the full sequence-based haplogroups (although a more detailed haplogroup assignment could be achieved from the sequence data as expected); accordingly, the regions of bio-geographic ancestry derived from the assay-inferable haplogroups were in agreement with the individuals' sampling origins (Table 4). For example, sample HGDP01076 is an individual from Sardinia (Italy) whose full mtDNA sequence can be classified as haplogroup J2b1a; our assays would predict the haplogroup of this person as J with Western Eurasian geographic origin. Notably, the HGDP samples from Pakistan exhibit both Western Eurasian and Southern Asian haplogroups (for example, HGDP00163 belongs to Western Eurasian haplogroup H2a and HGDP00165 belongs to Southern Asian haplogroup M30), consistent with previous observations (see Discussion above). Similarly, the Bedouin samples belong to both African as well as Western Eurasian haplogroups.

Conclusions

We developed an efficient and sensitive method for the multiplex genotyping of informative mtDNA SNPs, allowing for the inference of a person's matrilineal bio-geographic ancestry at a continental level. We would like to emphasize that matrilineal ancestry must be seen as reflecting only one aspect of the overall bio-geographic ancestry of a person [5, 6, 46]. A more accurate establishment of the overall bio-geographic ancestry is achievable when mtDNA is used in conjunction with informative Y-chromosomal (in the case of males) [8] and autosomal ancestry-informative DNA markers [47–50], especially when a person's biological ancestors are from different geographic regions resulting in mixed bio-geographic ancestry.

Methods

Reaction conditions

Multiplex PCR amplification was carried out in a reaction volume of 6 μL, containing 1x GeneAmp PCR Gold buffer (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA), 4.5 mM MgCl2 (Applied Biosystems), 100 μM of each dNTP (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), 0.35 units of AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems), 0.001 to 1 ng genomic DNA template, and PCR primers (desalted; Metabion, Martinsried, Germany) in concentrations as specified in Tables 1, 2, 3. The reactions were performed in a Dual 384-well GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems) using optical 384-well reaction plates (Applied Biosystems), with the following cyclic conditions: 10 min at 95°C; followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 15 s; 60°C for 45 s; and a final extension at 60°C for 5 min. PCR products were purified by adding 1.5 μL ExoSAP-IT (USB Corporation, OH, USA) to 6 μL PCR product, followed by incubation at 37°C for 15 min and 80°C for 15 min. Multiplex single-base primer extension was carried out in a reaction volume of 5 μL, containing 1 μL SNaPshot Ready Reaction Mix (Applied Biosystems), 1 μL purified PCR product and extension primers (HPLC-purified; Metabion, Martinsried, Germany) in concentrations as specified in Tables 1, 2, 3. The reactions were performed in a Dual 384-well GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems) using optical 384-well reaction plates (Applied Biosystems), with the following cycling conditions: 2 min at 96°C; followed by 25 cycles of 96°C for 10 s; 50°C for 5 s; and 60°C for 30 s. The reaction products were purified by adding 1 unit of Shrimp Alkaline Phosphatase (USB Corporation) to 5 μL of extension product, followed by incubation at 37°C for 45 min and 75°C for 15 min. PCR and extension primer details can be found in Table 1 for Multiplex 1, in Table 2 for Multiplex 2 and in Table 3 for Multiplex 3.

Extended primers were separated by capillary electrophoresis on a 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) using POP-7 polymer by loading a mixture of 1 μL purified extension product, 8.8 μL Hi-Di formamide (Applied Biosystems) and 0.2 μL GeneScan-120 LIZ internal size standard (Applied Biosystems). Results were analysed using GeneMapper version 3.7 software (Applied Biosystems).

Dilution series

For the purpose of sensitivity testing, genomic DNA from four individuals of different matrilineal continental origin was extracted from buccal swabs. For each individual, the DNA was diluted to obtain a solution of precisely 1 ng/μL as determined by two independent Quantifiler (Applied Biosystems) measurements. All Quantifiler assays were carried out according to manufacturer's recommendations. A dilution series was made from each of the four 1 ng/μL DNA solutions, producing concentrations of 0.25, 0.063, 0.016, 0.004 and 0.001 ng/μL for each individual. Concentrations of the dilutions were measured again and confirmed by triplicate Quantifiler measurements. The Quantifiler assays were carried out according to the manufacturer's recommendations, except for the addition of two extra dilutions to the recommended standard curve to be able to measure the very low DNA concentrations.

Abbreviations

- HVS:

-

hypervariable segment

- mtDNA:

-

mitochondrial DNA

- mtSNP:

-

mitochondrial SNP

- np:

-

nucleotide position

- NRY:

-

non-recombining portion of the Y-chromosome

- PCR:

-

polymerase chain reaction

- SNP:

-

simple nucleotide polymorphism

- STR:

-

short tandem repeat.

References

Budowle B, van Daal A: Forensically relevant SNP classes. BioTechniques. 2008, 44: 603-610. 10.2144/000112806.

Budowle B, Bieber FR, Eisenberg AJ: Forensic aspects of mass disasters: strategic considerations for DNA-based human identification. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2005, 7: 230-243.

Cavalli-Sforza LL, Feldman MW: The application of molecular genetic approaches to the study of human evolution. Nat Genet. 2003, 33 (Suppl): 266-275. 10.1038/ng1113.

Underhill PA, Kivisild T: Use of Y chromosome and mitochondrial DNA population structure in tracing human migrations. Annu Rev Genet. 2007, 41: 539-564. 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130407.

Shriver MD, Kittles RA: Genetic ancestry and the search for personalized genetic histories. Nat Rev Genet. 2004, 5: 611-618. 10.1038/nrg1405.

Royal CD, Novembre J, Fullerton SM, Goldstein DB, Long JC, Bamshad MJ, Clark AG: Inferring genetic ancestry: opportunities, challenges and implications. Am J Hum Genet. 2010, 86: 661-673. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.03.011.

van Oven M, Kayser M: Updated comprehensive phylogenetic tree of global human mitochondrial DNA variation. Hum Mutat. 2009, 30: E386-E394. 10.1002/humu.20921.

Karafet TM, Mendez FL, Meilerman MB, Underhill PA, Zegura SL, Hammer MF: New binary polymorphisms reshape and increase resolution of the human Y chromosomal haplogroup tree. Genome Res. 2008, 18: 830-838. 10.1101/gr.7172008.

Matsuda H, Yukawa N: Mitochondrial analysis in forensic science. Molecular Forensics. Edited by: Rapley R, Whitehouse D. 2007, Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, b127-140.

Corach D, Lao O, Bobillo C, van Der Gaag K, Zuniga S, Vermeulen M, van Duijn K, Goedbloed M, Vallone PM, Parson W, et al: Inferring continental ancestry of Argentineans from autosomal, Y-chromosomal and mitochondrial DNA. Ann Hum Genet. 2010, 74: 65-76. 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2009.00556.x.

Lao O, Vallone PM, Coble MD, Diegoli TM, van Oven M, van der Gaag KJ, Pijpe J, de Knijff P, Kayser M: Evaluating self-declared ancestry of US Americans with autosomal, Y-chromosomal and mitochondrial DNA. Hum Mutat. 2010, 31: E1875-E1893. 10.1002/humu.21366.

Oota H, Settheetham-Ishida W, Tiwawech D, Ishida T, Stoneking M: Human mtDNA and Y-chromosome variation is correlated with matrilocal versus patrilocal residence. Nat Genet. 2001, 29: 20-21. 10.1038/ng711.

Hurles ME, Sykes BC, Jobling MA, Forster P: The dual origin of the Malagasy in Island Southeast Asia and East Africa: evidence from maternal and paternal lineages. Am J Hum Genet. 2005, 76: 894-901. 10.1086/430051.

Nuñez C, Baeta M, Sosa C, Casalod Y, Ge J, Budowle B, Martínez-Jarreta B: Reconstructing the population history of Nicaragua by means of mtDNA, Y-chromosome STRs and autosomal STR markers. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2010, 143: 591-600.

Brandstätter A, Niederstätter H, Pavlic M, Grubwieser P, Parson W: Generating population data for the EMPOP database - an overview of the mtDNA sequencing and data evaluation processes considering 273 Austrian control region sequences as example. Forensic Sci Int. 2007, 166: 164-175.

Dario P, Bom J, Ribeiro T, Geada H: MtSNP typing before mtDNA sequencing: Why do it?. Forensic Sci Int Genet Suppl Series. 2009, 2: 187-188. 10.1016/j.fsigss.2009.08.137.

Köhnemann S, Pfeiffer H: Application of mtDNA SNP analysis in forensic casework. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2010,

Brandstätter A, Parsons TJ, Parson W: Rapid screening of mtDNA coding region SNPs for the identification of west European Caucasian haplogroups. Int J Legal Med. 2003, 117: 291-298.

Grignani P, Turchi C, Achilli A, Peloso G, Alù M, Ricci U, Robino C, Pelotti S, Carnevali E, Boschi I, et al: Multiplex mtDNA coding region SNP assays for molecular dissection of haplogroups U/K and J/T. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2009, 4: 21-25. 10.1016/j.fsigen.2009.04.001.

Behar DM, Rosset S, Blue-Smith J, Balanovsky O, Tzur S, Comas D, Mitchell RJ, Quintana-Murci L, Tyler-Smith C, Wells RS: The Genographic Project public participation mitochondrial DNA database. PLoS Genet. 2007, 3: e104-10.1371/journal.pgen.0030104.

Olivieri A, Achilli A, Pala M, Battaglia V, Fornarino S, Al-Zahery N, Scozzari R, Cruciani F, Behar DM, Dugoujon J, et al: The mtDNA legacy of the Levantine early Upper Palaeolithic in Africa. Science. 2006, 314: 1767-1770. 10.1126/science.1135566.

Achilli A, Perego UA, Bravi CM, Coble MD, Kong Q, Woodward SR, Salas A, Torroni A, Bandelt HJ: The phylogeny of the four pan-American mtDNA haplogroups: implications for evolutionary and disease studies. PLoS ONE. 2008, 3: e1764-10.1371/journal.pone.0001764.

Sanchez JJ, Endicott P: Developing multiplexed SNP assays with special reference to degraded DNA templates. Natl Protoc. 2006, 1: 1370-1378. 10.1038/nprot.2006.247.

Untergasser A, Nijveen H, Rao X, Bisseling T, Geurts R, Leunissen JAM: Primer3Plus, an enhanced web interface to Primer3. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35: W71-W74. 10.1093/nar/gkm306.

Goios A, Prieto L, Amorim A, Pereira L: Specificity of mtDNA-directed PCR-influence of NUclear MTDNA insertion (NUMT) contamination in routine samples and techniques. Int J Legal Med. 2008, 122: 341-345. 10.1007/s00414-007-0191-5.

Vallone PM, Butler JM: AutoDimer: a screening tool for primer-dimer and hairpin structures. BioTechniques. 2004, 37: 226-231.

Rowold DJ, Luis JR, Terreros MC, Herrera RJ: Mitochondrial DNA geneflow indicates preferred usage of the Levant Corridor over the Horn of Africa passageway. J Hum Genet. 2007, 52: 436-447. 10.1007/s10038-007-0132-7.

Plaza S, Calafell F, Helal A, Bouzerna N, Lefranc G, Bertranpetit J, Comas D: Joining the pillars of Hercules: mtDNA sequences show multidirectional gene flow in the western Mediterranean. Ann Hum Genet. 2003, 67: 312-328. 10.1046/j.1469-1809.2003.00039.x.

Turchi C, Buscemi L, Giacchino E, Onofri V, Fendt L, Parson W, Tagliabracci A: Polymorphisms of mtDNA control region in Tunisian and Moroccan populations: an enrichment of forensic mtDNA databases with Northern Africa data. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2009, 3: 166-172. 10.1016/j.fsigen.2009.01.014.

Comas D, Plaza S, Wells RS, Yuldaseva N, Lao O, Calafell F, Bertranpetit J: Admixture, migrations, and dispersals in Central Asia: evidence from maternal DNA lineages. Eur J Hum Genet. 2004, 12: 495-504. 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201160.

Quintana-Murci L, Chaix R, Wells RS, Behar DM, Sayar H, Scozzari R, Rengo C, Al-Zahery N, Semino O, Santachiara-Benerecetti AS, et al: Where West meets East: the complex mtDNA landscape of the Southwest and Central Asian corridor. Am J Hum Genet. 2004, 74: 827-845. 10.1086/383236.

Alves-Silva J, da Silva Santos M, Guimarães PE, Ferreira AC, Bandelt HJ, Pena SD, Prado VF: The ancestry of Brazilian mtDNA lineages. Am J Hum Genet. 2000, 67: 444-461. 10.1086/303004.

Stefflova K, Dulik MC, Pai AA, Walker AH, Zeigler-Johnson CM, Gueye SM, Schurr TG, Rebbeck TR: Evaluation of group genetic ancestry of populations from Philadelphia and Dakar in the context of sex-biased admixture in the Americas. PLoS ONE. 2009, 4: e7842-10.1371/journal.pone.0007842.

Kayser M, Brauer S, Cordaux R, Casto A, Lao O, Zhivotovsky LA, Moyse-Faurie C, Rutledge RB, Schiefenhoevel W, Gil D, et al: Melanesian and Asian origins of Polynesians: mtDNA and Y chromosome gradients across the Pacific. Mol Biol Evol. 2006, 23: 2234-2244. 10.1093/molbev/msl093.

Malyarchuk BA, Grzybowski T, Derenko MV, Czarny J, Miścicka-Sliwka D: Mitochondrial DNA diversity in the Polish Roma. Ann Hum Genet. 2006, 70: 195-206. 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00222.x.

Malyarchuk BA, Derenko M, Perkova M, Grzybowski T, Vanecek T, Lazur J: Reconstructing the phylogeny of African mitochondrial DNA lineages in Slavs. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008, 16: 1091-1096. 10.1038/ejhg.2008.70.

Vallone PM, Just RS, Coble MD, Butler JM, Parsons TJ: A multiplex allele-specific primer extension assay for forensically informative SNPs distributed throughout the mitochondrial genome. Int J Legal Med. 2004, 118: 147-157. 10.1007/s00414-004-0428-5.

Quintáns B, Alvarez-Iglesias V, Salas A, Phillips C, Lareu MV, Carracedo A: Typing of mitochondrial DNA coding region SNPs of forensic and anthropological interest using SNaPshot minisequencing. Forensic Sci Int. 2004, 140: 251-257.

Alvarez-Iglesias V, Jaime JC, Carracedo A, Salas A: Coding region mitochondrial DNA SNPs: targeting East Asian and Native American haplogroups. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2007, 1: 44-55. 10.1016/j.fsigen.2006.09.001.

Schlebusch CM, Naidoo T, Soodyall H: SNaPshot minisequencing to resolve mitochondrial macro-haplogroups found in Africa. Electrophoresis. 2009, 30: 3657-3664. 10.1002/elps.200900197.

Collins PJ, Hennessy LK, Leibelt CS, Roby RK, Reeder DJ, Foxall PA: Developmental validation of a single-tube amplification of the 13 CODIS STR loci, D2S1338, D19S433 and amelogenin: the AmpFlSTR Identifiler PCR Amplification Kit. J Forensic Sci. 2004, 49: 1265-1277. 10.1520/JFS2002195.

Krenke BE, Viculis L, Richard ML, Prinz M, Milne SC, Ladd C, Gross AM, Gornall T, Frappier JRH, Eisenberg AJ, et al: Validation of male-specific, 12-locus fluorescent short tandem repeat (STR) multiplex. Forensic Sci Int. 2005, 151: 111-124. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.02.008.

Mulero JJ, Chang CW, Lagacé RE, Wang DY, Bas JL, McMahon TP, Hennessy LK: Development and validation of the AmpFlSTR MiniFiler PCR Amplification Kit: a MiniSTR multiplex for the analysis of degraded and/or PCR inhibited DNA. J Forensic Sci. 2008, 53: 838-852. 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2008.00760.x.

Cann HM, de Toma C, Cazes L, Legrand M, Morel V, Piouffre L, Bodmer J, Bodmer WF, Bonne-Tamir B, Cambon-Thomsen A, et al: A human genome diversity cell line panel. Science. 2002, 296: 261-262. 10.1126/science.296.5566.261b.

Hartmann A, Thieme M, Nanduri LK, Stempfl T, Moehle C, Kivisild T, Oefner PJ: Validation of microarray-based resequencing of 93 worldwide mitochondrial genomes. Hum Mutat. 2009, 30: 115-122. 10.1002/humu.20816.

Balding D, Weale M, Richards M, Thomas M: Genetic and isotopic analysis and the UK Border Agency. Significance. 2010, 7: 58-61. 10.1111/j.1740-9713.2010.00419.x.

Lao O, van Duijn K, Kersbergen P, de Knijff P, Kayser M: Proportioning whole-genome single-nucleotide-polymorphism diversity for the identification of geographic population structure and genetic ancestry. Am J Hum Genet. 2006, 78: 680-690. 10.1086/501531.

Halder I, Shriver M, Thomas M, Fernandez JR, Frudakis T: A panel of ancestry informative markers for estimating individual biogeographical ancestry and admixture from four continents: utility and applications. Hum Mutat. 2008, 29: 648-658. 10.1002/humu.20695.

Kosoy R, Nassir R, Tian C, White PA, Butler LM, Silva G, Kittles R, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, Gregersen PK, Belmont JW, et al: Ancestry informative marker sets for determining continental origin and admixture proportions in common populations in America. Hum Mutat. 2009, 30: 69-78. 10.1002/humu.20822.

Paschou P, Lewis J, Javed A, Drineas P: Ancestry informative markers for fine-scale individual assignment to worldwide populations. J Med Genet. 2010, 47: 835-847. 10.1136/jmg.2010.078212.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded in part by the Netherlands Forensic Institute (NFI) and received additional support from a grant from the Netherlands Genomics Initiative (NGI)/Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) within the framework of the Forensic Genomics Consortium Netherlands (FGCN).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MVO designed the method and drafted the manuscript. MV tested and optimized the method. MK conceived the study and contributed to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

van Oven, M., Vermeulen, M. & Kayser, M. Multiplex genotyping system for efficient inference of matrilineal genetic ancestry with continental resolution. Investig Genet 2, 6 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/2041-2223-2-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2041-2223-2-6