Abstract

Background

Patients at higher than average risk of heritable cancer may process risk information differently than the general population. However, little is known about clinical, demographic, or psychosocial predictors that may impact risk perception in these groups. The objective of this study was to characterize factors associated with perceived risk of developing cancer in groups at high risk for cancer based on genetics or family history.

Methods

We searched Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, Ovid PsycInfo, and Scopus from inception through April 2009 for English-language, original investigations in humans using core concepts of "risk" and "cancer." We abstracted key information and then further restricted articles dealing with perceived risk of developing cancer due to inherited risk.

Results

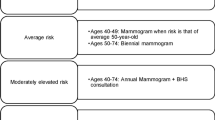

Of 1028 titles identified, 53 articles met our criteria. Most (92%) used an observational design and focused on women (70%) with a family history of or contemplating genetic testing for breast cancer. Of the 53 studies, 36 focused on patients who had not had genetic testing for cancer risk, 17 included studies of patients who had undergone genetic testing for cancer risk. Family history of cancer, previous prophylactic tests and treatments, and younger age were associated with cancer risk perception. In addition, beliefs about the preventability and severity of cancer, personality factors such as "monitoring" personality, the ability to process numerical information, as well as distress/worry also were associated with cancer risk perception. Few studies addressed non-breast cancer or risk perception in specific demographic groups (e.g. elderly or minority groups) and few employed theory-driven analytic strategies to decipher interrelationships of factors.

Conclusions

Several factors influence cancer risk perception in patients at elevated risk for cancer. The science of characterizing and improving risk perception in cancer for high risk groups, although evolving, is still relatively undeveloped in several key topic areas including cancers other than breast and in specific populations. Future rigorous risk perception research using experimental designs and focused on cancers other than breast would advance the field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Perceived risk is an important subjective psychological phenomenon related to threat appraisal that is closely intertwined with judgments about susceptibility to disease as well as the probability of benefit from interventions [1]. It remains an integral component of several theories of health behavior (e.g. the Health Belief Model, the Precaution Adoption Model, or the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping) [2]. Thus, risk perception is an essential component of health behavior in cancer generally, and in hereditary cancers in particular.

Compared to cancer risk perception in the general population, experiencing a close family member going through treatment for cancer or having a known genetic susceptibility to cancer has life-altering implications, including how one processes risk information [3]. At-risk family members or those with known mutations may have to make important decisions based upon their risk perceptions, including whether to undergo prophylactic surgery or subsequent genetic testing, whether to disclose test results to family members, or whether to participate in experimental cancer screening (e.g. spiral computed tomography). Moreover, misperception of risk has been shown to both increase and decrease use of preventive health services and therefore can have significant implications for the health of those at greater than average risk of developing cancer.

The existing research on cancer risk perception is scattered across disciplines (i.e. health services research, psychooncology, health communication) and across populations (i.e. cancer patients and the general public) [2]. In a recent narrative review, Klein and Stefanek discuss the role of innumeracy, heuristics, motivational factors, and emotional influences in shaping risk perception and the implications for cancer risk perception [4]. They conclude that the psychology of risk perception should elicit caution among clinicians hoping to accurately convey risk information to patients and call for a research strategy that spans the fields of medical decision-making and health communication.

The little remaining empirical literature synthesizing data regarding cancer risk perception either focuses on a specific cancer such as breast cancer [5], or describes interventions to improve risk communication in cancer. However, little is said about the key clinical, demographic, or psychosocial predictors that may shape risk perception [6], all of which are critical factors for tailoring interventions that align patients' perceptions of risk with their calculated risk [7].

We undertook a systematic review to rigorously characterize the existing empirical literature on factors that may influence perceived risk of getting cancer for those at high risk for cancer in order to form an empirically-grounded conceptual model for future cancer risk communication research.

Methods

The report of this protocol-driven systematic review adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [8]. Protocol details are available upon request.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible if they evaluated associations between psychosocial, clinical, or demographic factors and cancer risk perception (or similar terms such as perceived susceptibility or risk interpretation). Eligible studies sampled individuals who had one or more known or suspected non-modifiable risks for hereditary cancer such as family history or having a positive genetic test. We excluded studies that sampled exclusively from the general population, average risk populations, or healthcare providers. We initially included studies regardless of their design or sample size and excluded review articles, commentaries, letters not containing original data, and studies that were exclusively qualitative due to the unfeasibility of data abstraction. We excluded studies in which the focus was on establishing associations of risk factors with outcomes or behaviors if they did not evaluate predictors of risk perception, interpretation or communication. Similarly, we excluded educational interventions aimed exclusively at raising awareness of risk. The characteristics of reviewed studies are provided in Table 1.

Search strategy

An expert reference librarian designed and conducted an electronic search strategy with input from study investigators focused on factors that may influence risk perception relevant to clinical care. We searched Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, Ovid PsycInfo, and Scopus from inception through April 2009. Only English language articles were selected. The core concepts were risk (MeSH term: risk management) and cancer (MeSH terms: neoplasms limited to diagnosis, treatment, epidemiology prognosis, mortality). A series of terms and text words were added such as patient education, attitude of patients and health care personnel, educational status, comprehension, communication in the context of decision making, choice, preferences, and uncertainty. In addition, we sought additional references from bibliographies of eligible studies and content experts. A detailed list of subject headings and text words is available upon request.

Assessment of study eligibility

Teams of two reviewers working independently and in duplicate screened all abstracts and titles and, upon retrieval of candidate studies, reviewed the full text to determine eligibility. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or by arbitration through a third reviewer. The mean chance-adjusted agreement (kappa) was 0.70.

Data extraction and synthesis

Teams used standardized forms to extract descriptive, methodological, and key variable data from all eligible studies. We used an online reference management system for systematic reviews to conduct study selection and data extraction (SRS 4.0 Mobius Analytics, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada).

Data collected from the vetted studies included study design, description of the population, description of the risk of cancer, analytical techniques, and the theoretical model tested. From each study, we extracted data regarding the type and strength of associations between psychosocial, clinical, and/or demographic factors and cancer risk perception, interpretation and/or communication. Disagreements between reviewers at this stage were also resolved by discussion or third-reviewer arbitration.

Considering the heterogeneity of the included studies in terms of design, population, type of cancer and outcome measures, and because the review was designed to generate (not test) hypotheses for future research, we did not conduct a meta-analysis. Data were tabulated and categorized according to the factors that affected risk perception. Narrative synopses describing the tested associations and the main findings of each study are presented (Tables 2 & 3). These summaries provided the empirical basis upon which to build a conceptual model of factors influencing risk perception in cancer (Figure 1). Since the included studies were mostly of a cross-sectional design, the quality of evidence was considered to be low and at high risk of bias. Therefore we did not extract data about bias protection measures in the included studies.

Results

Search results

Our search identified 1028 candidate articles for abstract review. After screening abstracts (when present), we excluded 524 articles and retrieved 504 full text articles. Of these, 184 fulfilled the basic inclusion criteria, but 131 of these were excluded for being exclusively qualitative, addressing risk perception among healthcare providers, including exclusively patients who already had cancer or patients with one or more modifiable risks for cancer, such as smoking. This left 53 articles that met all inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 2). Of those 53 studies, 36 reported participants with elevated risk who had not undergone genetic testing, and 17 reported participants who had undergone genetic testing.

Study designs

Table 1 describes the characteristics of the 53 included studies. Most of the studies (92%) had an observational study design and only four were experimental.

Study populations

Thirty-eight studies (70%) reported exclusively female populations, with most (14) of the remaining 16 including both genders. The majority (67%) included race information, but relatively few included non-white populations and made race-related inferences.

Cancers

The majority of studies (64%) addressed risk perception of breast cancer, followed by ovarian cancer (often along with breast cancer risk) (30%), colorectal cancer (23%), and prostate cancer (4%). Some studies examined multiple cancers.

Risk perception measures & theories

A range of self-reported measures of risk perception were employed across studies. These measures used a variety of total item numbers, categorical as well as continuous variables, and in some cases asked patients to estimate their absolute risk while in others participants were asked to compare their risk to a relevant comparison group (comparative risk). Thirty-seven studies used a single item measure of risk perception, 11 used two measures, three used three measures, and one study used four measures. Twenty-two studies assessed accuracy of risk perception. Of these, six were in studies where subjects had undergone some kind of genetic testing. We provide further details of risk perception measures in an accompanying appendix (see Additional file 1: Appendix).

Only 7 studies in our review referenced a specific theoretical model of health behavior as motivating or informing their research. These included the health belief model [9–13], the theory of planned behavior/theory of reasoned action [12, 14], the cognitive behavioral model of health anxiety [15], and the precaution adoption model [16].

The major clinical, demographic, and psychosocial factors influencing risk perception in patient populations at high risk for cancer are described below. Tables 2 and 3 show results of the review stratified by risk perception in those who had not undergone genetic susceptibility testing as well as risk perception in those who had undergone such testing. Any differences between groups are discussed in the text.

Clinical factors

A variety of clinical factors were associated with cancer risk perception. The most common association included a family history of cancer or precancerous lesions (n = 11). Others included type of cancer [3], objective cancer risk (e.g. from the Gail Model) [17–19], having received genetic counseling or written documentation of genetic testing results [20–23], and family history of death from the cancer of interest [19]. Clinical factors influencing risk perception among those who had undergone genetic susceptibility testing focussed primarily on the extent to which having undergone testing itself was a predictor of risk perception [17, 18, 24]. In several studies of patients with strong family history but no genetic testing, the retrospective observation of having undergone screening, prophylactic surgery, or biopsy was associated with risk perception [25–27].

Demographic factors

Age

Ten studies examined associations between age and risk perception with variable findings. For instance, Rimes et al found that, among those with a family history of colon cancer, younger age predicted greater perceived risk of developing cancer [15]. Likewise, Lerman et al found that women in the 30-34 and 50+ categories were less likely to perceive themselves as having an elevated risk than were women in other age groups [28]. No studies tested the association between age and accuracy of risk perception.

Gender

Just two studies examined associations between gender and risk perception. Domanska noted that men and women differed in the proportions of those who perceived their lifetime risk of colorectal cancer as being greater than 60%, but these differences were not significant [29]. Since only 20% of all the studies focused on risk perception of non gender-specific cancers, there was minimal opportunity to evaluate the role of gender in cancer risk perception.

Race/Ethnicity

Only four studies explored the relationship between race/ethnicity and risk perception. Haas found that black women were less likely than white women to accurately perceive risk [30]; Mellon found that being Caucasian was associated with higher risk perception [3]; Blalock found that whites in a high risk group were more likely than blacks in the same group to rate heredity as a risk-increasing factor [14]. Others tested but did not find significant associations between race/ethnicity and risk perception [31, 32].

Other Demographic Factors

Some studies also tested for associations between other demographic factors and cancer risk perception. Rowe tested but did not find any association between marital status, employment status and risk perception [31], while Glanz et al found that having a college education was directly associated with higher colorectal cancer risk perception [16].

Psychosocial Factors

In addition to clinical and demographic factors that may influence risk perception, several key psychosocial factors were also identified. These include cognitive, affective, as well as personality and coping factors.

Cognitive

Beliefs about the nature of the participant's condition and its preventability were occasionally examined. Codori found that those who believed colorectal cancer was less preventable expressed a higher perceived risk of the disease [33]. Degree of awareness of one's family history or the hereditary nature of one's risk were also positively associated with risk perception [14, 16].

Affective

Distress, anxiety and worry have been consistently associated with risk perception in multiple studies. Lebel found that overestimation of risk was associated with greater distress among those undergoing biopsy of breast lesions [34]. Audrain studied women with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer and found similar results [35].

Some studies (n = 3) examined the association between risk perception and existing measures of distress including the Impact of Events Scale (with the intrusion and avoidance subscales) [19, 36, 37], and the Total Mood Disturbance scale from the Profile of Mood States (POMS-TMD) [38]. Andrykowski showed a negative association between perceived risk and avoidance among women who had undergone biopsy [36]. That is, the greater the perceived risk, the less propensity for avoidance behavior. In contrast, Zakowski found that those whose parents had died of cancer had the highest levels of intrusive thoughts, avoidance and perceived risk [19].

Vernon's study of men at high risk of colorectal cancer [27] and Collins' study of patients presenting at a genetic testing clinic [39] showed that perceived risk was directly associated with worry about being diagnosed with colorectal cancer. Rimes, Beebe-Dimmer, and Bratt came to similar conclusions with analogous affective measures [15, 40, 41].

Personality and Coping

A few studies showed that the encoding pattern of "monitoring," (i.e., scanning for, attending to, and amplifying cancer threats) [42, 43] as well as specific coping styles [33, 44] were also correlated with higher risk perception. Finally, two studies showed an inverse relationship between spirituality/spiritual coping and risk perception [45, 46], suggesting a possible relationship between belief systems and interpretation of risk.

Discussion

In this systematic review of 53 studies of patients at high risk for cancer we identified several key clinical, demographic, and psychosocial factors associated with perceived risk of acquiring cancer in these patient populations. These are depicted in Figure 1. These results highlight known and unknown factors related to the science of risk perception assessment in patients at higher than average risk for cancer.

Most of the studies evaluated in this review used an observational design studying mostly women and their perceived risk of developing breast or ovarian cancer often in the context of genetic testing. In contrast, little literature was found on factors influencing risk perception of acquiring other common cancers such as prostate and colorectal cancer. Clinical factors associated with cancer risk perception included the extent of family history, as well as previous preventive tests and treatments. Demographic factors including age, race/ethnicity, and education level may play a role in risk perception. No studies were designed to assess factors influencing risk perception in a prospective and stratified manner for groups such as ethnic minorities or elderly populations.

Based on this literature, cognitive factors including beliefs about the preventability and severity of the condition, as well as the ability to process numerical information may be important in risk perception. We also observed consistently reported associations between affective factors such as distress, depression, worry and risk perception. These are perhaps the best characterized factors influencing cancer risk perception in high risk patients. A limited number of personality and coping factors may also relate to risk perception.

Our findings complement those of previous systematic reviews by highlighting the strides taken in describing key factors influencing cancer risk perception, especially affective factors. Like Vernon, we focused on key cognitive and affective correlates of cancer risk perception in hopes that a more complete description of such factors could empirically inform future interventions. Unlike Vernon, we focused on groups at high risk, believing the specific needs of these populations are under-explored, increasingly salient, and distinct from the general population. Katapodi found weak but significant associations between perceived risk and age, education, race, and worry; our findings five years later across multiple cancers demonstrate analogous associations. Each of these domains deserves further exploration in longitudinal and experimental studies.

These data suggest several limitations of the current literature on cancer risk perception among those with a potential inherited predisposition to cancer. Taking the next step in improving the measurement of risk perception such as better discriminating between the merits of rating comparative risk versus estimating objective risk could help standardize the cancer risk perception literature. Another limitation to current conceptions of risk relates to current modes of measurement which are generally uni-dimensional (i.e. measuring magnitude or frequency of risk, but not both) and/or contain only single item measures. Multi-dimensional measures that capture frequency, magnitude, as well as individual- and social-level aspects of risk perception need to be developed and utilized. In addition, few studies employed sophisticated measurement or analytic techniques like latent variable modeling, path analysis, or the like. Along with experimental study designs in which investigators would specify a priori hypothesized relationships and the direction of those relationships, these techniques would provide a sound basis for causal inferences related to risk perception research to be made.

Finally, this systematic review did not identify potential rich networks of social and behavioral influences that may cause some persons to deeply engage with their risk, while others seem to push it aside. Such dynamics related to the salience of perceived risk information would be important to address in more sophisticated analyses that contextualize risk in the broad fabric of patients' lives and social networks.

Clinical Implications

Research defining correlates of perceived risk of acquiring cancer among those with elevated cancer susceptibility suggest several clinical implications. Interventions to address perceived risk of developing cancer among high risk populations should not only rely on facts about clinical and demographic characteristics, but also on the real psychosocial factors that may influence risk perception for those at high risk for cancer. Risk perception is not merely a cognitive process, but an affective and existential one. The relationship between worry and risk perception that we so consistently observed suggests that worry may influence screening behaviors among high risk patients regardless of the whether sound evidence exists for the clinical utility of those screening tests, such as in the case of direct-to-consumer genomic testing. This creates tensions for practicing clinicians who strive to judiciously utilize tests in a manner consistent with the best available evidence and the patient's values. Risk perception is an unavoidably affectively-loaded filter and is thus quite susceptible to manipulation and distortion, making approaches to informed decision-making that acknowledge and work in concert with these influences in high risk populations especially challenging and necessary.

Conclusions

Overall, these data suggest that the science of characterizing and improving risk perception in cancer, although evolving, is still relatively undeveloped at least in several key clinical topic areas. First, future studies focusing on cancer risk perception among men, racially/ethnically diverse populations that experience cancer disparities and the elderly would add considerable value to the literature. Research dedicated to risk perception related to specific topics such as adoption of lifestyle behaviors, the use of complementary/integrative medicine, genomic technologies in prediction and prognostication, or participation in research studies including chemoprevention would have potentially wide-reaching implications for cancer control initiatives.

References

Weinstein ND, Klein WM: Resistance of personal risk perceptions to debiasing interventions. Health Psychol 1995,14(2):132–40.

Vernon SW: Risk perception and risk communication for cancer screening behaviors: a review. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 1999, 25: 101–19.

Mellon S, Gold R, Janisse J, Cichon M, Tainsky MA, Simon MS, et al.: Risk perception and cancer worries in families at increased risk of familial breast/ovarian cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2008,17(8):756–66. 10.1002/pon.1370

Klein WM, Stefanek ME: Cancer risk elicitation and communication: lessons from the psychology of risk perception. CA Cancer J Clin 2007,57(3):147–67. 10.3322/canjclin.57.3.147

Katapodi MC, Lee KA, Facione NC, Dodd MJ: Predictors of perceived breast cancer risk and the relation between perceived risk and breast cancer screening: a meta-analytic review. Prev Med 2004,38(4):388–402. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.012

Edwards A, Elwyn G: Understanding risk and lessons for clinical risk communication about treatment preferences. Qual Health Care 2001,10(Suppl 1):i9–13.

Stanton AL: Psychosocial concerns and interventions for cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 2006,24(32):5132–7. 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8775

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009,151(4):W64. 264–9

Cappelli M, Surh L, Walker M, Korneluk Y, Humphreys L, Verma S, et al.: Psychological and social predictors of decisions about genetic testing for breast cancer in high-risk women. Psychology, Health & Medicine 2001,6(3):321–33.

Cappelli M, Verma S, Korneluk Y, Hunter D, Tomiak E, Allanson J, et al.: Psychological and genetic counseling implications for adolescent daughters of mothers with breast cancer. Clinical Genetics 2005,67(6):481–91. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2005.00456.x

Martin W, Degner L: Perception of risk and surveillance practices of women with a family history of breast cancer. Cancer Nursing 2006,29(3):227–35. 10.1097/00002820-200605000-00010

Matloff ET, Moyer A, Shannon KM, Niendorf KB, Col NF: Healthy women with a family history of breast cancer: Impact of a tailored genetic counseling intervention on risk perception, knowledge, and menopausal therapy decision making. Journal of Women's Health 2006,15(7):843–56. 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.843

Salsman JM, Pavlik E, Boerner LM, Andrykowski MA: Clinical, demographic, and psychological characteristics of new, asymptomatic participants in a transvaginal ultrasound screening program for ovarian cancer. Preventive Medicine 2004,39(2):315–22. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.023

Blalock SJ, DeVellis BM, Afifi RA, Sandler RS: Risk perceptions and participation in colorectal cancer screening. Health Psychology 1990,9(6):792–806.

Rimes KA, Salkovskis PM, Jones L, Lucassen AM: Applying a cognitive-behavioral model of health anxiety in a cancer genetics service. Health Psychology 2006,25(2):171–80.

Glanz K, Grove J, Marchand LL, Gotay C: Underreporting of family history of colon cancer: Correlates and implications. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention 1999,8(7):635–9.

Codori AM, Petersen GM, Miglioretti DL, Larkin EK, Bushey MT, Young C, et al.: Attitudes toward colon cancer gene testing: Factors predicting test uptake. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention 1999,8(4 II):345–51.

VanDijk S, Otten W, Zoeteweij MW, Timmermans DRM, Asperen CJV, Breuning MH, et al.: Genetic counselling and the intention to undergo prophylactic mastectomy: Effects of a breast cancer risk assessment. British Journal of Cancer 2003,88(11):1675–81. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600988

Zakowski SG, Valdimarsdottir HB, Bovbjerg DH, Borgen P, Holland J, Kash K, et al.: Predictors of intrusive thoughts and avoidance in women with family histories of breast cancer. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 1997,19(4):362–9. 10.1007/BF02895155

Bjorvatn C, Eide GE, Hanestad BR, Oyen N, Havik OE, Carlsson A, et al.: Risk perception, worry and satisfaction related to genetic counseling for hereditary cancer. Journal of Genetic Counseling 2007,16(2):211–22. 10.1007/s10897-006-9061-4

Emery J, Morris H, Goodchild R, Fanshawe T, Prevost AT, Bobrow M, et al.: The GRAIDS trial: A cluster randomised controlled trial of computer decision support for the management of familial cancer risk in primary care. British Journal of Cancer 2007,97(4):486–93. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603897

Lobb EA, Butow PN, Barratt A, Meiser B, Gaff C, Young MA, et al.: Communication and information-giving in high-risk breast cancer consultations: Influence on patient outcomes. British Journal of Cancer 2004,90(2):321–7. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601502

Watson M, Lloyd S, Davidson J, Meyer L, Eeles R, Ebbs S, et al.: The impact of genetic counselling on risk perception and mental health in women with a family history of breast cancer. British Journal of Cancer 1999,79(5–6):868–74.

DiProspero LS, Seminsky M, Honeyford J, Doan B, Franssen E, Meschino W, et al.: Psychosocial issues following a positive result of genetic testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations: Findings from a focus group and a needs-assessment survey. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2001,164(7):1005–9.

Elit L, Esplen MJ, Butler K, Narod S: Quality of life and psychosexual adjustment after prophylactic oophorectomy for a family history of ovarian cancer. Familial Cancer 2001,1(3–4):149–56.

Hatcher MB, Fallowfield L, A'Hern R: The psychosocial impact of bilateral prophylactic mastectomy: Prospective study using questionnaires and semistructured interviews. BMJ 2001,322(7278):76. 10.1136/bmj.322.7278.76

Vernon SW, Myers RE, Li BCTaS: Factors associated with perceived risk in automotive employees at increased risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention 2001,10(1):35–43.

Lerman C, Kash K, Stefanek M: Younger women at increased risk for breast cancer: perceived risk, psychological well-being, and surveillance behavior. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs 1994, 16: 171–6.

Domanska K, Nilbert M, Soller M, Silfverberg B, Carlsson C: Discrepancies between estimated and perceived risk of cancer among individuals with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Genetic Testing 2007,11(2):183–6. 10.1089/gte.2007.9999

Haas JS, Kaplan CP, Jarlais GD, Gildengoin V, Perez-Stable EJ, Kerlikowske K: Perceived risk of breast cancer among women at average and increased risk. Journal of Women's Health 2005,14(9):845–51. 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.845

Rowe JL, Montgomery GH, Duberstein PR, Bovbjerg DH: Health locus of control and perceived risk for breast cancer in healthy women. Behavioral Medicine 2005,31(1):33–40. 10.3200/BMED.31.1.33-42

Royak-Schaler R, Klabunde CN, Greene WF, Lannin DR, DeVellis B, Wilson KR, et al.: Communicating breast cancer risk: patient perceptions of provider discussions. Volume 7. Medscape Womens Health; 2002:2.

Codori AM, Waldeck T, Petersen GM, Miglioretti D, Trimbath JD, Tillery MA: Genetic counseling outcomes: perceived risk and distress after counseling for hereditary colorectal cancer. J Genet Couns 2005,14(2):119–32. 10.1007/s10897-005-4062-2

Lebel S, Jakubovits G, Rosberger Z, Loiselle C, Seguin C, Cornaz C, et al.: Waiting for a breast biopsy: Psychosocial consequences and coping strategies. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2003,55(5):437–43. 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00512-9

Audrain J, Schwartz MD, Lerman C, Hughes C, Peshkin BN, Biesecker B: Psychological distress in women seeking genetic counseling for breast-ovarian cancer risk: The contributions of personality and appraisal. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 1997,19(4):370–7. 10.1007/BF02895156

Andrykowski MA, Carpenter JS, Studts JL, Cordova MJ, Cunningham LLC, Beacham A, et al.: Psychological impact of benign breast biopsy: A longitudinal, comparative study. Health Psychology 2002,21(5):485–94.

Cunningham LL, Andrykowski MA, Wilson JF, McGrath PC, Sloan DA, Kenady DE: Physical symptoms, distress, and breast cancer risk perceptions in women with benign breast problems. Health Psychology 1998,17(4):371–5.

Erblich J, Bovbjerg DH, Valdimarsdottir HB: Looking forward and back: Distress among women at familial risk for breast cancer. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 2000,22(1):53–9. 10.1007/BF02895167

Collins V, Halliday J, Warren R, Williamson R: Cancer worries, risk perceptions and associations with interest in DNA testing and clinic satisfaction in a familial colorectal cancer clinic. Clinical Genetics 2000,58(6):460–8.

Beebe-Dimmer JL, Wood DP, Gruber SB, Chilson DM, Zuhlke KA, Claeys GB, et al.: Risk Perception and Concern among Brothers of Men with Prostate Carcinoma. Cancer 2004,100(7):1537–44. 10.1002/cncr.20121

Bratt O, Damber JE, Emanuelsson M, Kristoffersson U, Lundgren R, Olsson H, et al.: Risk perception, screening practice and interest in genetic testing among unaffected men in families with hereditary prostate cancer. European Journal of Cancer 2000,36(2):235–41. 10.1016/S0959-8049(99)00272-5

Miller SM, Fleisher L, Roussi P, Buzaglo JS, Schnoll R, Slater E, et al.: Facilitating informed decision making about breast cancer risk and genetic counseling among women calling the NCI's cancer information service. Journal of Health Communication 2005,10(Suppl1):119–36.

Schwartz MD, Lerman C, Miller SM, Daly M, Masny A: Coping disposition, perceived risk, and psychological distress among women at increased risk for ovarian cancer. Health Psychology 1995,14(3):232–5.

O'Neill SC, DeMarco T, Peshkin BN, Rogers S, Rispoli J, Brown K, et al.: Tolerance for uncertainty and perceived risk among women receiving uninformative BRCA1/2 test results. American Journal of Medical Genetics, Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics 2006,142(4):251–9.

Quillin JM, McClish DK, Jones RM, Burruss K, Bodurtha JN: Spiritual coping, family history, and perceived risk for breast cancer - Can we make sense of it? Journal of Genetic Counseling 2006,15(6):449–60. 10.1007/s10897-006-9037-4

Schwartz MD, Hughes C, Roth J, Main D, Peshkin BN, Isaacs C, et al.: Spiritual faith and genetic testing decisions among high-risk breast cancer probands. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention 2000,9(4):381–5.

Gil F, Mendez I, Sirgo A, Llort G, Blanco I, Cortes-Funes H: Perception of breast cancer risk and surveillance behaviours of women with family history of breast cancer: A brief report on a Spanish cohort. Psycho-Oncology 2003,12(8):821–7. 10.1002/pon.704

Fang CY, Miller SM, Malick J, Babb J, Engstrom PF, Daly MB: Psychosocial correlates of intention to undergo prophylactic oophorectomy among women with a family history of ovarian cancer. Preventive Medicine 2003,37(5):424–31. 10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00163-4

Wellisch DK, Lindberg NM: A psychological profile of depressed and nondepressed women at high risk for breast cancer. Psychosomatics: Journal of Consultation Liaison Psychiatry 2001,42(4):330–6.

Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Ubel PA, Smith DM, Derry HA, McClure JB, Stark A, et al.: Communicating side effect risks in a tamoxifen prophylaxis decision aid: The debiasing influence of pictographs. Patient Education and Counseling 2008,73(2):209–14. 10.1016/j.pec.2008.05.010

Stefanek ME, Helzlsouer KJ, Wilcox PM, Houn F: Predictors of and satisfaction with bilateral prophylactic mastectomy. Prev Med 1995,24(4):412–9. 10.1006/pmed.1995.1066

Bondy ML, Vogel VG, Haiabi S, Lustbader ED: Identification of women at increased risk for breast cancer in a population-based screening program. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention 1992,1(2):143–7.

Lipkus I, Klein W: Effects of communicating social comparison information on risk perceptions for colorectal cancer. Journal of Health Communication 2006,11(4):391–407. 10.1080/10810730600671870

Cameron LD, Reeve J: Risk perceptions, worry, and attitudes about genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility. Psychology and Health 2006,21(2):211–30. 10.1080/14768320500230318

Madalinska JE, Hollenstein J, Bleiker E, Beurden MV, Valdimarsdottir HB, Massuger LF, et al.: Quality-of-life effects of prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy versus gynecologic screening among women at increased risk of hereditary ovarian cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2005,23(28):6890–8. 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.626

Peterson SK, Pentz RD, Marani SK, Ward PA, Blanco AM, LaRue D, et al.: Psychological functioning in persons considering genetic counseling and testing for Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Psycho-Oncology 2008,17(8):783–9. 10.1002/pon.1352

Claes E, Denayer L, Evers-Kiebooms G, Boogaerts A, Legius E: Predictive testing for hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer: Motivation, illness representations and short-term psychological impact. Patient Education and Counseling 2004,55(2):265–74. 10.1016/j.pec.2003.11.002

Bruno M, Tommasi S, Stea B, Quaranta M, Schittulli F, Mastropasqua A, et al.: Awareness of breast cancer genetics and interest in predictive genetic testing: A survey of a southern Italian population. Annals of Oncology 2004,15(Suppl. 1):i48-i54.

Hensley ML, Robson ME, Kauff ND, Korytowsky B, Castiel M, Ostroff J, et al.: Pre- and postmenopausal high-risk women undergoing screening for ovarian cancer: Anxiety, risk perceptions, and quality of life. Gynecologic Oncology 2003,89(3):440–6. 10.1016/S0090-8258(03)00147-1

VanOostrom I, Meijers-Heijboer H, Duivenvoorden HJ, Broecker-Vriends AH, vanAsperen CJ, Sijmons RH, et al.: Comparison of individuals opting for BRCA1/2 or HNPCC genetic susceptibility testing with regard to coping, illness perceptions, illness experiences, family system characteristics and hereditary cancer distress. Patient Education and Counseling 2007,65(1):58–68. 10.1016/j.pec.2006.05.006

Acknowledgements and Funding

This publication was made possible by Mayo Clinic Department of Medicine funding to Dr. Tilburt and from career development funding to Drs. Tilburt and Ehlers from Grant Number 1 KL2 RR024151 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH. Information on NCRR is available at http://www.ncrr.nih.gov/. Information on Reengineering the Clinical Research Enterprise can be obtained from http://nihroadmap.nih.gov. Dr. Tilburt had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JT conceived of the study and, along with PE, MM, designed the study search strategy. JT, KJ, PS, DE, BC, JC, SE, and KN reviewed study abstracts and extracted data from full text articles. ML assisted with acquisition of articles and helped design data abstraction forms. JT, KJ, PS, DE, KN, and MM helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Tilburt, J.C., James, K.M., Sinicrope, P.S. et al. Factors Influencing Cancer Risk Perception in High Risk Populations: A Systematic Review. Hered Cancer Clin Pract 9, 2 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1897-4287-9-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1897-4287-9-2