Abstract

We studied the origin of deep groundwater in the Joban and Hamadori areas in southern Tohoku, Japan, based on δD, δ18O, 129I/I, 36Cl/Cl, and 3H concentrations. Deep groundwater was collected from the basement rocks (Cretaceous granite) and from the margin of the Joban sedimentary basin (latest Cretaceous to Quaternary sedimentary rocks deposited on the basement rocks). We sampled groundwater pumped from depths ranging from 350 to 1,600 m in these areas. A hypothetical end-member of deep groundwater was estimated from the relationship between δ18O and Cl concentrations, and our data reveal a much higher iodine concentration and lower Br and Cl concentrations than found in seawater. The iodine ages inferred from 129I/I are quite uniform and are about 40 Ma and 36Cl/Cl almost reached the secular equilibrium. The relationship between iodine and Cl can be explained by mixing a hypothetical end-member with meteoric water or seawater. Moreover, the I/Cl ratio increases linearly with increasing water temperature. The water temperature was high in Joban, with a maximum of 78°C at a depth of 1,100 m. The geothermal gradient in the Joban basin is 18°C km-1, and the temperature even at a depth of 3 km in the basin was not high enough to supply thermal water to the sampling sites. Thus, sedimentary rocks in the Joban basin are unlikely to be the source of iodine in the deep groundwater. Several active faults such as the Futaba Fault are developed in and around the studied areas. The Iwaki earthquake occurred 1 month after the 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake, and normal-fault type surface ruptures formed and discharged hot groundwater in Joban. The deep groundwater we studied probably came up through the basement rocks from greater depths. There are no sedimentary rocks younger than Tertiary age beneath the pre-Cretaceous basement rocks, and the subducted sediments in the Japan Trench are a possible source of iodine in the groundwater. The Joban and Hamadori areas may be an ideal window to look into the water circulation in the forearc of the Tohoku subduction zone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The cosmogenic isotopes 129I and 36Cl have been used to investigate the origin of water, such as water found in crustal fluids, oil fields, and geothermal fluids. The half-lives of 129I and 36Cl are 15.7 and 0.3 million years, respectively. According to Muramatsu and Wedepohl (1998), the largest reservoir of iodine in the earth's crust is in ocean sediments. Iodine-rich brine is often generated in forearc and back-arc areas and passive continental margins (Muramatsu et al.2001; Tomaru et al.2007a,[b],[c],2009a,[b]; Fehn et al.2003,2007a,[b]; Fehn2012). Fehn (2012) reported that the iodine-rich fluids in the forearc regions in several subduction zones have iodine ages of about 40 to 60 Ma regardless of the ages of the subducting slab and proposed that the ages represent ‘a global pattern of migration of fluids from deep, old layers located in the upper plates.’ On the other hand, Muramatsu et al. (2001) proposed that iodine-rich brine produced in Chiba Prefecture, Japan was derived from subducted marine sediments, because the iodine ages are considerably older than the ages of the host formations. They also suggested that the recycling of iodine could occur in forearc areas and that this process should be considered for the marine iodine budget. Iodine is a biophilic element and is strongly enriched in organic matters (Elderfield and Truesdale1980). Sediments on continental margins are enriched with iodine because of higher organic content and higher depositional rates than in open oceans (Martin et al.1993; Fehn et al.2007b). Thus, subducted marine sediments in the open ocean may not provide iodine to the forearc regions. However, Premuzic et al. (1982) and Klauda and Sandler (2005) report fairly high organic carbon in surface sediments over a wide area of the northwestern margin of the Pacific Plate (several times as high as in open oceans), even far east of the outer rise in the Japan Trench. Thus, we do not consider that ‘subducted sediments’ are excluded as possible iodine sources, at least in the Tohoku subduction zone.

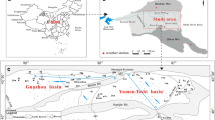

We searched for the origin of iodine in deep groundwater collected from hot springs in the Joban and Hamadori areas in southern Tohoku, Japan, by measuring the 129I/I, 36Cl/Cl, δD, δ18O, and 3H concentrations. Most of our samples are hot spring water pumped from the Cretaceous granite (Figure 1a). There are no sedimentary rocks (possible sources of iodine) younger than the Tertiary beneath the granitic basement, and geologically this is a unique aspect of the study area. We also sampled groundwater pumped from sedimentary rocks at the margin of the Joban sedimentary basin where the latest Cretaceous to Quaternary sedimentary sequences were deposited on the basement rocks (Figure 1b; Inaba et al.2009). Natural gas was produced in the Joban basin until 2007 at Iwaki-oki gas field, located at the central part of the basin. This paper compares deep groundwater with different host rocks and discusses the source of iodine contained in the water.

Geological setting. (a) A simplified geological and geographical map of the Fukushima-Ibaraki area and sampling localities 1 to 12; an inset figure shows the location of the study area (box), southern Tohoku, Japan, with plate configurations. On-land geological map is simplified from GeomapNavi (2014). Miocene volcanic rocks are widely distributed in the Abukuma belt but are not shown in (a) to highlight the basement rocks. The sampling area is divided into areas A to E, and an asterisk indicates the epicenter of the Iwaki Earthquake (Japan Meteorological Agency2011). The Fukushima First and Second Nuclear Power Plants are located at FNPP1 and FNPP2, respectively, in area A. (b) A schematic geologic cross section across the offshore Joban basin after Inaba et al. (2009). Ages of sediments are given on each formation.

Both Joban and Hamadori are located along the Pacific coast of Ibaraki and Fukushima Prefectures in southern Tohoku where several active faults, including the Futaba Fault, are distributed (Figure 1a; The Research Group for Active Faults of Japan1991; GeomapNavi2014). The temperature of the hot spring water we sampled in Joban is high, with a maximum of 78°C at a depth of 1,100 m, probably because the areas are tectonically active (there are no nearby active volcanoes). Moreover, the 11 April 2011 Iwaki earthquake (Mw 6.6), an aftershock of the 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake (Mw 9.0), occurred in Iwaki City (Fukushima et al.2013), and the surface ruptures and crustal deformation with normal displacements formed along the Itozawa and Yunodake Faults (Kobayashi et al.2012; Toda and Tsutsumi2013) near our sampling sites in Joban (Figure 1a). The earthquake discharged thermal water in the city with a flow rate reaching about 10,000 m3 day-1 in May 2011 (Sato et al.2011; Kazahaya et al.2013). The massive discharge of water suggests that the tectonic activity promotes upward movement of deep groundwater in the areas. We examine the origin of deep groundwater in both Joban and Hamadori areas in view of their geological and tectonic settings, as well as their isotope compositions.

Methods

Geological settings and water samples

The Joban and Hamadori areas are located in the northeastern part of Ibaraki Prefecture and the southeastern part of Fukushima Prefecture, Japan (Figure 1a). The Joban sedimentary basin is located offshore and consists of a nearly continuous sequence of sedimentary rocks of about 5,000-m maximum thickness that has been deposited on the basement rocks since late the Cretaceous (Figure 1b; Inaba et al.2009). The Maastrichtian-Paleogene coals and coaly mudstones are the most likely sources of natural gas (Iwata et al.2002). Inaba et al. (2009) demonstrated that the Cretaceous argillaceous rocks in the basin can potentially generate petroleum if there is abundant marine organic matter deposited in an anoxic environment. The Abukuma belt is located west of the Joban basin and consists of metamorphic rocks and Cretaceous granite (e.g., Hiroi et al.1998). The Hatagawa Fault is considered to be the boundary between the Abukuma and Southern Kitakami Belts (e.g., Tomita et al.2002). However, we treat basements rocks in the two belts and those beneath the Joban basin as ‘pre-Cretaceous basement rocks’ in this study. Coastal areas, including our sampling sites, are covered with thin Tertiary sedimentary rocks and Quaternary sediments (green and white areas, respectively, in Figure 1a; GeomapNavi2014). Those sedimentary rocks cover the pre-Cretaceous basement rocks and constitute the western margin of the Joban basin. Active faults are shown with red lines in Figure 1a.

We sampled deep groundwater at ten hot spring wells in areas A and B in Hamadori, and in areas C and D in Joban, and river water at two locations in area E in Hamadori (Figure 1a; numbers 1 to 12 indicate sampling localities). We also use the sampling localities as sample numbers (Table 1, column 2). Hot spring drill holes penetrate through surface sediments into granitic basement in areas A, C, and D and into sedimentary rocks of the Joban basin in area B. The depth of the basement granite was about 800 m in a drill hole very close to locality 2 (Yanagisawa et al.1989) and 1,100 to 1,200 m at the western part of Fukushima First and Second Nuclear Power Plant sites (FNPP1 and FNPP2 in Figure 1a; Tokyo Electric Company2012). The pumping depths in area A are 1,200 to 1,600 m (Table 1, column 3), and our groundwater samples in area A were collected from the upper part of the granite basement. According to the information on drilling at a hot spring (locality 5), the hot spring water in area B is pumped from the Oligocene Iwaki formation in the landward margin of the Joban basin (cf. Figure 1b). The drilling depths for hot springs in area C are not clear, but we obtained information at a hot spring facility that the water is pumped from the basement granite. The depth of the basement metamorphic rocks is about 800 m in area D, but those rocks are thermally metamorphosed and may be close to granite (Kasai2008). Thus, we consider that the groundwater in area D was sampled from metamorphic or granitic basement rocks. However, groundwater sampled at a depth of 350 m was collected from sedimentary rocks in the Joban basin.

We sampled the hot spring water pumped from the depths shown in the third column of Table 1. Because of the limited sample volumes during the first sampling, we collected more samples later. However, the δD, δ18O, elemental concentration, and temperature for these locations showed small temporal variations even before and after the 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake, so we treated the data collected at different times in the same way. Table 1 also summarizes the sampling dates, chemical data, and estimated iodine age.

Methods for chemical and isotope analyses

Hydrogen and oxygen isotope compositions (δD and δ18O) were measured by mass spectrometry or cavity ring-down spectroscopy. The CO2/H2O equilibrium method and the H2 reduction method using Cr metal were used for the analyses of oxygen and hydrogen isotopes, respectively (mass spectrometers, Delta Plus and Delta V advantage; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The precision of these measurements was ±0.1‰ for δ18O and ±1‰ for δD. Oxygen and hydrogen isotope compositions are presented in the δ notation in per mille relative to the Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (V-SMOW). The precision for the analysis by cavity ring-down spectroscopy (Picarro cavity ring-down spectrometer L2120-i; Picarro Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) was ±0.1‰ for δ18O and ±0.6‰ for δD. For the analysis of I, Br, and Cl, water samples were filtered using 0.45-μm membrane filters. Iodine concentrations in the groundwater samples were determined by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (Agilent 7700; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Groundwater samples were diluted with 0.5 wt.% tetramethylammonium hydroxide and spiked with Re as an internal standard. Cl and Br concentrations were determined by ion chromatography (Dionex, DX-500; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

To determine iodine age, 129I/I ratios of deep groundwater were measured by accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS), using the sample preparation scheme developed by Muramatsu et al. (2008). Groundwater samples were purified by solvent extraction and back extraction using CCl4. Purified iodine was precipitated as AgI by adding AgNO3, and the AgI precipitate was washed with ultrapure water and NH4OH. The supernatant was removed after centrifugation, and the AgI was freeze-dried. The 129I/I ratio was measured at the Micro Analysis Laboratory Tandem Accelerator (MALT) at the University of Tokyo, following the method detailed in Matsuzaki et al. (2007).

The 36Cl/Cl ratios of the samples were measured by AMS at the Australian National University (Fifield et al.2010) or at the Purdue Rare Isotope Measurement Laboratory (PRIME Lab), Purdue University, USA (Sharma et al.2000) to investigate the age of Cl. The samples were acidified with concentrated HNO3 to precipitate AgCl by adding AgNO3. The AgCl precipitate was separated by centrifugation and dissolved in NH4OH. The SO42- was precipitated as BaSO4 by adding a saturated Ba(NO3)2 solution to remove isobaric interference from 36S, and the BaSO4 precipitate was eliminated by filtration. The AgCl was precipitated again and separated by centrifugation before drying. Sample numbers 11 and 12 were prepared following the procedures described in Tosaki et al. (2011), and their 36Cl/Cl were measured with the AMS system at the Tandem Accelerator Complex, University of Tsukuba (Sasa et al.2010). Isotope 3H is one of the most commonly employed radioisotopes used to identify the presence of a modern water component. The 3H concentrations in groundwater were measured after electrolytic enrichment, using a liquid scintillation analyzer (Packard 3100TR, PerkinElmer 1220 Quantulus (PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), or LSC-LB5 (Hitachi Aloka Medical, Ltd., Mitaka, Tokyo, Japan).

Results

Isotope compositions and the estimation of hypothetical end-members

Figure 2 exhibits isotope and chemical compositions of groundwater from areas A to D. The d parameter (d = δD - 8δ18O) after Dansgaard (1964) is mostly in the range of 15 to 20 for the Abukuma area (Takahashi et al.2004) and 10 to 12 for the Kanto Plain (Inamura and Yasuhara2003). The δ18O values of several samples collected from the A and D areas are slightly heavier than the meteoric water lines using d values of 10 and 20 (MWL in Figure 2a). The positive shift of δ18O can be explained by isotopic exchange between water and rock (Figure 2a), and this characteristic is often found in connate water such as oil field brine (Clayton et al.1966; Mahara et al.2012). The relationship between the Cl and δ18O of the samples from areas A and B cannot be explained by simple mixing between meteoric water and seawater (Figure 2b). The Cl concentration of the hypothetical end-member was determined to be 361 mM by extrapolating the best-fit line for the data from area D to 0‰ of δ18O. Higher Cl in some data from areas A and B may be due to the mixing of seawater through the sedimentary rocks.

The concentration of Br correlates well with that of Cl (correlation coefficient, R = 0.99), suggesting simple mixing between the meteoric water and seawater (Figure 2c). On the other hand, the iodine concentration in deep groundwater is much higher than in meteoric water and seawater (Figure 2d). The highest iodine concentration was approximately 150 times higher than the seawater value. The I and Br concentrations of the hypothetical end-members were inferred from the mixing lines between the meteoric water and data from area D (asterisks in Figure 2c,d), using the Cl concentration at the end-member in Figure 2b. The Br and Cl concentrations of the hypothetical end-members are diluted (Figure 2c). The I and Cl concentrations for some samples from areas A and B can be explained by the mixing of the hypothetical end-member (asterisk), meteoric water (filled black circle), and seawater (filled black square), except for two samples with low I and Cl concentrations (Figure 2d). In contrast, those for samples from areas C and D in granitic basement can be explained by the mixing of the hypothetical end-member with meteoric water.Figure 3 exhibits an interesting correlation among the four areas. The I/Cl increases with increasing temperature of deep groundwater, and the ratio and temperature for areas C and D are much higher than for areas A and B.

Relationship between I/Cl weight ratio and temperature of deep groundwater. Seawater temperature (4°C) was calculated as an annual average of seawater off Fukushima Prefecture, at a depth of 400 m in 2013, using data from the Japan Meteorological Agency (2013).

Age of I estimated from 129I/I

We estimated the ages of I in the deep groundwater from the measured 129I/I of the water samples. Three gray curves in Figure 4 indicate mixing lines, on logarithmic scales, of the water sample with the highest iodine content (number 2 in Table 1), with the anthropogenic meteoric water, pre-anthropogenic seawater, and pre-anthropogenic meteoric water. Snyder and Fehn (2004) report five 129I/I values of anthropogenic meteoric water in Japan that vary widely from 2.0 × 10-10 to 7.9 × 10-9 (cross marks in Figure 4a). We did not measure the 129I/I of meteoric water, using their lowest value instead, because it falls on the mixing line. To draw the other two mixing lines, we used a reported value of 129I/I (1.5 × 10-12) for the pre-anthropogenic water (Moran et al.1998; Fehn et al.2007a) and iodine concentrations of Abukuma River near the sampling site after Tagami and Uchida (2006) and typical seawater (Table 1). The results for the samples from areas A, B, and D can be explained by the mixing of the water with the highest iodine content with the pre-anthropogenic meteoric and seawater (Figure 4). This is consistent with the relationship between iodine and Cl in Figure 2d. The two samples from area C have higher 129I/I values (green filled circles in Figure 4) than the pre-anthropogenic water. They also contained detectable 3H (half-life: 12.32 years) of 1.28 ± 0.04 and 0.6 ± 0.1 TU, where 1 TU is defined as the ratio of 1 tritium atom to 1018 hydrogen atoms. Thus, the water from area C is likely to have mixed with shallow groundwater containing anthropogenic 129I, and we did not use them for the age determination. Sample number 6 from area B contained detectable 3H, but no significant contamination of anthropogenic 129I was recognized.

Mixing diagrams in the 129I/I versus 1/I space (a) and (b) is the enlarged portion of (a). Lines indicate mixing between pre-anthropogenic meteoric water, seawater, and anthropogenic meteoric water with the highest I samples. Ages above the dashed lines indicate iodine ages, as determined from Equation 1.

Iodine age was calculated by the decay equation:

where R obs is the measured 129I/I, R i is the initial 129I/I (assumed to be 1.5 × 10-12), and λ129 is a decay constant of 4.41 × 10-8 year-1 (Fehn2012). Most samples have a 129I/I value of (0.2 to 0.3) × 10-12 irrespective of the iodine concentration and I/Cl ratio (Figure 4b), which gives iodine ages of 36 to 46 Ma. We neglect fissiogenic 129I produced by spontaneous fission of 238U because its influence is small (Fehn et al.2000; Tomaru et al.2007a,[c],2009a,[b]). The homogeneity of iodine age (39 ± 4 Ma) suggests that the source of iodine is limited.

Secular equilibrium of 36Cl of the deep groundwater

We calculated the 36Cl/Cl ratios at secular equilibrium between the production and decay of 36Cl using the chemical compositions of the host rocks (Additional file1: Table S1). Figure 5 shows the relationships between 36Cl/Cl and 1/Cl for the samples from the four areas. The secular equilibrium 36Cl/Cl (Re) can be calculated by the following equation (Andrews et al.1986; Snyder and Fabryka-Martin2007; Morikawa and Tosaki2013):

Mixing diagrams in the 36Cl/Cl versus 1/Cl space. Horizontal lines indicate the secular equilibrium (Re) of 36Cl/Cl for granite and sedimentary rocks, estimated from the chemical compositions of host rocks (Additional file1: Table S1). Black-filled circles give the 36C/Cl and 1/Cl values of two river water samples collected in area E, representing the cosmogenic end-member. Lines indicate mixing between cosmogenic and modern seawater values after Fifield et al. (2013).

The thermal neutron absorption cross section of 35Cl (σ35Cl) is 43.6 × 10-24 cm2, the decay constant (λ36) of 36Cl is 2.3 × 10-6 year-1, and the isotopic abundance (N) of 35Cl is 0.7577. The thermal neutron flux (∅), in neutron per square centimeter per year, was estimated from the whole-rock major and trace element compositions of various sedimentary rocks and granitic rocks collected in this area (Additional file1: Table S1; Morikawa and Tosaki2013). The secular equilibrium 36Cl/Cl (R e ) are calculated and plotted as horizontal dashed lines for areas A, C, and D with granitic basement (R e = (1.77 ± 0.82) × 10-14), and as horizontal solid lines for area B with sedimentary rocks (R e = (9.87 ± 3.10) × 10-15) in Figure 5. The equilibrium between 36Cl production and decay is established in approximately 1.5 Ma (Andrews et al.1986). The 36Cl/Cl values of most of our samples are plotted at or near the horizontal lines, and they have nearly reached secular equilibrium. Note that a state of true equilibrium may not be attained with a single, specific type of host rock in a strict sense, possibly leading to some uncertainty in the above interpretation. Overall, the deep groundwater in the Joban and Hamadori area has not been affected by modern seawater, even though the areas are located near the coast.

Discussion

The origin of iodine

We discuss the possible sources of iodine in the deep groundwater collected at ten hot springs in the Joban and Hamadori areas and implications for water circulation in the Tohoku subduction zone. The measured concentrations of iodine in the groundwater were much higher than in seawater (Figure 2d), whereas Cl and Br concentrations were lower than in seawater (Figure 2b,c). Iodine is strongly bound to organic matter under marine conditions (Elderfield and Truesdale1980) and is released during the diagenesis of organic material to form natural water enriched in iodine, such as oil field brines and pore waters in marine sediments (e.g., Tomaru et al.2009a,[b]; Fehn2012). Previous papers report that Br is also released during decomposition of organic materials (Tomaru et al.2007c,2009b), but the enrichment of Br did not occur in the deep groundwater we studied. A possible reason for this is that the release rate of iodine from organic matter is higher than that of Br (Tomaru et al.2009b). The iodine of about 40 Ma in age in the deep groundwater must have derived from sedimentary rocks, and there are two possible sources, the Joban sedimentary basin, east of the hot springs where we did the sampling (Figure 1), and the subducted marine sediments from the Japan Trench beneath Tohoku, as discussed below.

We do not exclude the Joban basin as a possible iodine source, but we consider it unlikely for the following three reasons: (1) The lower Miocene formation in the Joban basin contains a thick layer of fine to coarse sandstone and conglomerate, which comprise a gas reservoir, and the iodine-containing water may have migrated up along the formation towards the hot spring wells where we sampled the deep groundwater (Figure 1b). However, the geothermal gradient at the Joban gas field (Figure 1a) is 18°C km-1 (Tanaka et al.2004), and the expected temperature at maximum depth (approximately 3 km) for the formation is about 70°C. This is lower than the temperature of the groundwater in area D (close to 80°C maximum, Figure 3), and the high temperature of the groundwater cannot be explained by the water in the Joban basin as its source (there is no heat source such as a volcano in the sampling area). (2) Deep groundwater samples in areas A, C, and D were collected in basement granitic rocks, but the temperature of the water is higher than that of water from the Joban sedimentary rocks in area B (Figure 3). Presumably, hot groundwater from depths comes up close to the surface in areas A, C, and D through the basement rocks. (3) Several active faults are developed in the sampled and neighboring areas, and surface ruptures formed along the Itozawa and Yunodake Faults during the 2011 Iwaki earthquake (red lines in Figure 1a; The Research Group for Active Faults of Japan1991; Toda and Tsutsumi2013). This earthquake discharged thermal water in Iwaki City for at least 2 years (Sato et al.2011; Kazahaya et al.2013). The earthquake was of a normal-fault type with complex ruptures and aftershocks extending to a depth of almost 15 km (Fukushima et al.2013). The active tectonics of the sampled areas must have promoted discharge of deep groundwater from depths through the basement rocks, rather than from the Joban basin. The geothermal gradients in the Joban-Hamadori areas are 24°C km-1 to 33°C km-1 (Tanaka et al.2004), but the temperature of the hot spring water is higher than the geothermal gradient in about half of the hot springs where we sampled groundwater (Figure 3).

The deep groundwater we sampled came through the pre-Cretaceous basement rocks. Thus, the geological situation in our study area is different from those studied by Fehn et al. (2003) and Tomaru et al. (2007b,2009a), who sampled pore waters in sediments on the continental slopes in the Nankai Trough and off the Shimokita Peninsula, northern Japan. In our study area, it is hard to expect sedimentary rocks younger than 40 Ma beneath the pre-Cretaceous basement. The subduction zone in the Japan Trench is regarded as a classical erosion boundary and sediments on the continental slope deposited on Cretaceous rocks (von Huene and Culotta1989). Moreover, von Huene and Lallemand (1990) proposed that the subduction of seamounts would play an important role in the erosion and estimated that the rate of tectonic erosion at a subducting plate boundary is comparable to the rate of sediment accretion. Thus, rocks constituting the upper plate in the Japan Trench are unlikely to be accreted large-scale sedimentary rocks, younger than the Cretaceous. However, a small-scale accretionary prism is developed throughout the Japan Trench, and a thin interplate layer, possibly composed of sedimentary rocks, is recognized along the plate interface down to a depth of almost 20 km (Figure 6; Tsuru et al.2002; Miura et al.2003). The types of subducting sediments are unclear in the southern part of the Japan Trench, but DSDP drilling at leg 56 site 436 revealed that incoming sediments are mostly pelagic sediments of a few hundred-meter thickness and of Miocene to Pliocene in age (about 20 to 2 Ma) (The Shipboard Scientific Party1980; Kimura et al.2012, Figures two panel b and four). Chester et al. (2013) report very similar sediments beneath the coseismic fault during the Tohoku-oki earthquake in the J-FAST drill cores in the Japan Trench. Moreover, sediments in the western Pacific Ocean near the Japanese Islands contain organic carbon of 0.5 to 1.0 wt.%, much higher than in sediments in the Pacific Ocean away from land (Premuzic et al.1982, Figure one; Klauda and Sandler2005, Figure three). We thus consider that subducted sediments in the Japan Trench are possible sources of iodine in the deep groundwater in the Joban-Hamadori areas.

Schematic figure of subduction zone in the southern part of the Japan Trench. The figure is constructed based on Figures ten panel a and fifteen of Miura et al. (2003) and Figure four of Tsuru et al. (2002) by expanding the original figure landward and depthward. Microearthquakes (gray circles) in the overlying plate and a branching fault (thick red line) are shown based on Imanishi et al. (2012). Active faults and coseismic faults during the 2011 Iwaki Earthquake are shown in red (Fukushima et al.2013). The trace of the Futaba Fault is drawn using a dipping angle and depth extent as determined by a recent seismic survey by Sato et al. (2013). The depth ranges for opal to quartz and smectite to illite transitions were drawn after Kimura et al. (2012). AF denotes the aseismic front after Yoshii (1975,1979).

Implications for water circulation in subduction zones

The subducted sediments undergo a series of dehydration reactions (Figure 6). Kimura et al. (2012) showed using a new temperature calculation that the opal A-CT-quartz transition and smectite-illite transition occur at the plate interface between 40 to 80 and 80 to 120 km, respectively, landward of the Japan Trench (Figure 6). The hypothetical end-member determined in this study shows higher iodine and lower Cl concentrations than seawater. The dehydration of hydrous minerals releases water and dilutes the Cl concentration in pore fluid; hence, the source of deep groundwater is probably deeper than those dehydration depths. Moreover, the isotope and trace element composition revealed the involvement of sediments in the generation of island-arc magma in northeast Japan (Shibata and Nakamura1997), strongly suggesting that the subduction component is carried to depths exceeding 150 km. The mantle wedge may be serpentinized, in view of a result of seismic wave tomography (Figure 6; e.g., Miura et al.2003), also suggesting the release of a large amount of water beneath the mantle wedge.

Microseismicity has been recognized in the mantle wedge to form the aseismic front (AF in Figure 6) roughly below the coastline (Yoshii1975,1979). Thus, the overriding plate off the coast of the study area is characterized by the mantle wedge and basement crust, both seismogenic, and slope sediments covering the basement rocks. Shale is very impermeable, particularly in the direction normal to the bedding plane (Kwon et al.2004a,[b] and references therein), and even the clay-bearing fault gouge has a permeability of as low as 10-17 to 10-22 m2 (Faulkner and Rutter2000). Therefore, fluids probably cannot easily penetrate through the slope sediments containing low-permeability shale, although we are not aware of any permeability data on the slope sediments in the Tohoku subduction zone, whereas fractured basement rocks have much higher permeability (e.g., 10-15 to 10-18 m2 in the case of cataclasite along the Median Tectonic Line; Uehara and Shimamoto2004). Hence, the overall permeability structures might have promoted fluid flow through fractured basement rocks from the subducting plate towards the coastline.

In addition, Imanishi et al. (2012) recognized that normal-fault type earthquakes had occurred locally in the Joban and Hamadori areas even before the 11 March 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake, despite the stress field in Tohoku being dominated by E to W compression. The 11 April 2011 Iwaki earthquake and associated surface ruptures were of normal-fault type (Fukushima et al.2013; Toda and Tsutsumi2013). Moreover, Imanishi et al. (2012) found a clear normal-fault type earthquake sequence extending from the subducting plate to the aftershock area and called it a branching fault (shown by a thick red line in Figure 6; small gray circles are aftershocks traced along profile EE’ in Figure four of their paper). The study area is the only place in the focal area of the Tohoku-oki earthquake where aftershocks are distributed continuously from the subducting plate to the coastal area of Tohoku. The branching fault is a broad zone of microseismicity and probably acted as a fluid conduit from the subducting plate to the study area. The discharge of a large amount of thermal water after the Iwaki earthquake (Sato et al.2011; Kazahaya et al.2013) strongly suggests that the earthquakes promote upward movement of deep groundwater in the areas. If the deep groundwater in the study area came out through the broad branching fault zone, the path of the water along the fault would be about 80 to 90 km. The ages of the incoming sediments range from 2 to 20 Ma, as reviewed above, and it takes about 2 Ma for the sediments to reach the intersection of the subducting plate and the branching fault. Thus, the iodine age of about 40 Ma gives 2 to 5 mm year-1 as the average speed of H2O migration in the overlying plate. The low speed may imply that fractures are sealed rapidly, and fault valve behavior (Sibson1992,2013) controls the fluid flow. Whether an average velocity of a few to several millimeters per year is appropriate or not needs a test from additional study in the future.

According to Kazahaya et al. (2014, Figure two panel B), the end-member of Arima-type deep-seated fluids in southwest Japan, which has been considered to be derived from the subducting Philippine Sea Plate, is within the range of magmatic gas in the δD to δ18O diagram. The values of δD and δ18O for our deep groundwater samples (Figure 2a) fall on the trends for altered seawater in their diagrams. In addition, our samples have lower Cl concentration than seawater, whereas the Cl concentration of Arima-type deep-seated fluids is more than 4 wt.% (Kazahaya et al.2014). It should be emphasized that the δD, δ18O, and Cl data of our samples do not have Arima-type deep-seated fluid characteristics, although they might have migrated through the mantle wedge. One possible cause of the difference is the difference in temperature between the Nankai Trough and Japan Trench; that is, the calculated temperature along the slab/mantle interface at a depth of 50 km is only 200°C in northeast Japan (Peacock and Wang1999). More detailed geochemical investigations need to be undertaken to determine the origin of iodine and fluid-flow paths in the Tohoku subduction zone. The Joban and Hamadori area, where we sampled deep groundwater from basement rocks, may be a good window to look into the fluid circulation in a subduction zone related to subducted sediments.

Conclusions

We measured δD, δ18O, 129I/I, 36Cl/Cl, and 3H concentrations in deep groundwater in the Joban and Hamadori areas in southern Tohoku and inferred the origin of iodine contained in the water. Main results are summarized as follows:

-

(1)

The hypothetical end-member of the groundwater, estimated from the relationship between Cl and δ18O, revealed much higher iodine and lower Cl concentrations in the groundwater than those in seawater. The I and Cl concentrations can be explained by the mixing of the hypothetical end-member, meteoric water, and seawater.

-

(2)

Ages of iodine in deep groundwater from the Joban and Hamadori areas were uniform and were approximately 40 Ma. Most of the 36Cl/Cl ratios were within a range of the secular equilibrium.

-

(3)

The I/Cl ratio of the deep groundwater increases with increasing temperature. The temperature of the groundwater is high with a maximum of 78°C at a depth of 1,100 m, and the groundwater in the Joban basin is unlikely to be a source of the groundwater in the study areas because the geothermal gradient (18°C km-1) of the basin is low. Basement rocks in the study areas are older than Cretaceous and cannot be a source of the iodine either.

-

(4)

Subducted sediments in the Japan Trench are a possible source of iodine in the groundwater because the sediments in the northwestern Pacific Ocean contain organic carbon as much as 0.5 to 1.0 wt.%. Active faults are developed in the study area and a large amount of groundwater was discharged during and after the 2011 Iwaki earthquake. Microseismicity was also recognized from the subducted plate all the way to the study area after the 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake. Those results and the iodine ages suggest that the groundwater migrated through fractured basement rocks from the subduction plate to the study areas at a rate of 2 to 5 mm year-1.

References

Andrews JN, Fontes J-Ch , Michelot J-L, Elmore D: In-situ neutron flux, 36Cl production and groundwater evolution in crystalline rocks at Stripa, Sweden. Earth Planet Sci Lett 1986, 77: 49–58. 10.1016/0012-821X(86)90131-7

Chester FM, Rowe C, Ujiie K, Kirkpatrick J, Regalla C, Remitti F, Moore JC, Toy V, Wolfson-Schwehr M, Bose S, Kameda J, Mori JJ, Brodsky EE, Eguchi N, Toczko S, Expedition 343 and 343T Scientists: Structure and composition of the plate-boundary slip zone for the 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake. Science 2013, 342: 1208–1211. 10.1126/science.1243719

Clayton RN, Friedman I, Graf DL, Mayeda TK, Meents WF, Shimp NF: The origin of saline formation waters 1. Isotopic composition. J Geophys Res 1966, 71: 3869–3882. 10.1029/JZ071i016p03869

Dansgaard W: Stable isotopes in precipitation. Tellus 1964, 16: 436–468. 10.1111/j.2153-3490.1964.tb00181.x

Elderfield H, Truesdale VW: On the biophilic nature of iodine in seawater. Earth Planet Sci Lett 1980, 50: 105–114. 10.1016/0012-821X(80)90122-3

Faulkner DR, Rutter EH: Comparisons of water and argon permeability in natural clay-bearing fault gouge under high pressure at 20°C. J Geophys Res 2000, 105: 16415–16426. 10.1029/2000JB900134

Fehn U: Tracing crustal fluids: applications of natural 129I and 36Cl. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 2012, 40: 45–67. 10.1146/annurev-earth-042711-105528

Fehn U, Snyder G, Egeberg PK: Dating of pore waters with 129I: relevance for the origin of marine gas hydrates. Science 2000, 289: 2332–2335. 10.1126/science.289.5488.2332

Fehn U, Snyder GT, Matsumoto R, Muramatsu Y, Tomaru H: Iodine dating of pore waters associated with gas hydrates in the Nankai area, Japan. Geology 2003, 31: 521–524. 10.1130/0091-7613(2003)031<0521:IDOPWA>2.0.CO;2

Fehn U, Moran JE, Snyder GT, Muramatsu Y: The initial 129I/I ratio and presence of ‘old’ iodine in continental margins. Nuc Inst Meth Phys Res B 2007, 259: 496–502. 10.1016/j.nimb.2007.01.191

Fehn U, Snyder GT, Muramatsu Y: Iodine as a tracer of organic material: 129I results from gas hydrate systems and fore arc fluid. J Geochem Explor 2007, 95: 66–80. 10.1016/j.gexplo.2007.05.005

Fifield LK, Tims SG, Fujioka T, Hoo WT, Everett SE: Accelerator mass spectrometry with the 14UD accelerator at the Australian National University. Nucl Instrum Meth Phys Res B 2010, 268: 858–862. 10.1016/j.nimb.2009.10.049

Fifield LK, Tims SG, Stone JO, Argento DC, Cesare MDe : Ultra-sensitive measurements of 36Cl and 236U at the Australian National University. Nucl Instrum Meth Phys Res B 2013, 294: 126–131.

Fukushima Y, Takada Y, Hashimoto M: Complex ruptures of the 11 April 2011 Mw 6.6 Iwaki earthquake triggered by the 11 March 2011 Mw 9.0 Tohoku earthquake, Japan. Bull Seismol Soc Am 2013, 103: 1572–1583. 10.1785/0120120140

Geochemical Earth Reference Model 2014.http://EarthRef.org/ EarthRef. org. . Accessed 05 May 2014

GeomapNavi: Geological survey of Japan, National Institute for Advanced Industrial Science and Technology. 2014. . Accessed 25 Apr 2014 https://gbank.gsj.jp/geonavi/ . Accessed 25 Apr 2014

Hiroi Y, Kishi S, Nohara T, Sato K, Goto J: Cretaceous high-temperature rapid loading and unloading in the Abukuma metamorphic terrane, Japan. J Metamorphic Geol 1998, 16: 67–81. 10.1111/j.1525-1314.1998.00065.x

Imanishi K, Ando R, Kuwahara Y: Unusual shallow normal-faulting earthquake sequence in compressional northeast Japan activated after the 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tohoku earthquake. Geophys Res Lett 2012., 39: L09306 L09306

Inaba T, Sampei Y, Nagamatsu T, Yonekura Y: Petroleum source-rock potential of the Cretaceous marine argillaceous rocks in the offshore Joban fore-arc Basin, northeast Japan. J Jpn Assoc Petrol Technol 2009, 74: 560–572. [in Japanese with English abstract] [in Japanese with English abstract] 10.3720/japt.74.560

Inamura A, Yasuhara M: Hydrogen and oxygen isotopic ratios of river water in the Kanto Plain and surrounding mountainous regions, Japan. J Jpn Assoc Hydrol Sci 2003, 33: 115–124. [in Japanese with English abstract] [in Japanese with English abstract]

Iwata T, Hirai A, Inaba T, Hirano M: Petroleum system in the offshore Joban Basin, northeast Japan. J Jpn Assoc Petrol Technol 2002, 67: 62–71. [in Japanese with English abstract] [in Japanese with English abstract]

Japan Meteorological Agency: Earthquake information. 2011. . Accessed 15 Apr 2014 http://www.data.jma.go.jp/svd/eqdb/data/shindo/index.php.

Japan Meteorological Agency : Daily surface seawater temperature in and around Japan. 2013. . Accessed 13 Jan 2014 http://www.data.jma.go.jp/gmd/kaiyou/data/db/kaikyo/daily/t100_jp.html.

Kasai K: Hot springs and geology of Ibaraki: exploration of heat source of hot springs from geological structures. Ibaraki Hot Spring Developer, Co. Ltd, Mito [in Japanese]; 2008.

Kazahaya K, Sato T, Takahashi M, Tosaki Y, Morikawa N, Takahashi H, Horiguchi K: Genesis of thermal water related to Iwaki-Nairiku earthquake. In Japan Geoscience Union Meeting. Makuhari Messe, Chiba:; 2013. 19–24 May 2013 19–24 May 2013

Kazahaya K, Takahashi M, Yasuhara M, Nishio Y, Inamura A, Morikawa N, Sato T, Takahashi HA, Kitaoka K, Ohsawa S, Oyama Y, Ohwada M, Tsukamoto H, Horiguchi K, Tosaki Y, Kirita T: Spatial distribution and feature of slab-related deep-seated fluid in SW Japan. J Jpn Assoc Hydrol Sci 2014, 44: 3–16. [in Japanese with English abstract] [in Japanese with English abstract]

Kimura G, Hina S, Hamada Y, Kameda J, Tsuji T, Kinoshita M, Yamaguchi A: Runaway slip to the trench due to rupture of highly pressurized megathrust beneath the middle trench slope: the tsunamigenesis of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake off the east coast of northern Japan. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2012, 339–340: 32–45.

Klauda JB, Sandler SI: Global distribution of methane hydrate in ocean sediment. Energy Fuels 2005, 19: 459–470. 10.1021/ef049798o

Kobayashi T, Tobita M, Koarai M, Okatani T, Suzuki A, Noguchi Y, Yamanaka M, Miyahara B: InSAR-derived crustal deformation and fault models of normal faulting earthquake (Mj 7.0) in the Fukushima-Hamadori area. Earth Planets Space 2012, 64: 1209–1221.

Kwon O, Kronenberg AK, Gangi AF, Johnson B, Herbert BE: Permeability of illite-bearing shale: 1. Anisotropy and effects of clay content and loading. J Geophys Res 2004., 109: B10205 B10205

Kwon O, Herbert BE, Kronenberg AK: Permeability of illite-bearing shale: 2. Influence of fluid chemistry on flow and functionally connected pores. J Geophys Res 2004., 109: B10206 B10206

Mahara Y, Ohta T, Tokunaga T, Matsuzaki H, Nakata E, Miyamoto Y, Mizuochi Y, Tashiro T, Ono M, Igarashi T, Nagao K: Comparison of stable isotopes, ratios of 36Cl/Cl and 129I/127I in brine and deep groundwater from the Pacific coastal region and the eastern margin of the Japan Sea. App Geochem 2012, 27: 2389–2402. 10.1016/j.apgeochem.2012.08.014

Martin JB, Gieskes JM, Torres M, Kastner M: Bromine and iodine in Peru margin sediments and pore fluids: implications for fluid origins. Geochim Cosmochim Ac 1993, 57: 4377–4389. 10.1016/0016-7037(93)90489-J

Matsuzaki H, Muramatsu Y, Kato K, Yasumoto M, Nakano C: Development of 129I-AMS system at MALT and measurements of 129I concentrations in several Japanese soils. Nucl Instr Meth Phys Res B 2007, 259: 721–726. 10.1016/j.nimb.2007.01.216

Miura S, Kodaira S, Nakanishi A, Tsuru T, Takahashi N, Hirata N, Kaneda Y: Structural characteristics controlling the seismicity of southern Japan Trench fore-arc region, revealed by ocean bottom seismographic data. Tectonophysics 2003, 363: 79–102. 10.1016/S0040-1951(02)00655-8

Moran JE, Fehn U, Teng RTD: Variations in 129I/127I ratios in recent marine sediments: evidence for a fossil organic component. Chem Geol 1998, 152: 193–203. 10.1016/S0009-2541(98)00106-5

Morgenstern U, Taylor CB: Ultra low-level tritium measurement using electrolytic enrichment and LSC. Isot Environ Health Stud 2009, 45: 96–117. 10.1080/10256010902931194

Morikawa N, Tosaki Y: Data set of the helium isotope production ratios and the secular equilibrium values of chlorine-36 isotopic ratios (36Cl/Cl) for the aquifer rocks in the Japanese islands: towards the improvement of the dating methods for old groundwaters. Open-file report of the geological survey of Japan. AIST 2013, 582: 1–21. [in Japanese with English abstract] [in Japanese with English abstract]

Muramatsu Y, Wedepohl KH: The distribution of iodine in the earth’s crust. Chem Geol 1998, 147: 201–216. 10.1016/S0009-2541(98)00013-8

Muramatsu Y, Fehn U, Yoshida S: Recycling of iodine in fore-arc areas: evidence from the iodine brines in Chiba, Japan. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2001, 192: 583–593. 10.1016/S0012-821X(01)00483-6

Muramatsu Y, Takada Y, Matsuzaki H, Yoshida S: AMS analysis of 129I in Japanese soil samples collected from background areas far from nuclear facilities. Quat Geochronol 2008, 3: 291–297. 10.1016/j.quageo.2007.08.002

Peacock SM, Wang K: Seismic consequences of warm versus cool subduction metamorphism: examples from southwest and northeast Japan. Science 1999, 286: 937–939. 10.1126/science.286.5441.937

Premuzic ET, Benkovitz CM, Gaffney JS, Walsh JJ: The nature and distribution of organic matter in the surface sediments of world oceans and seas. Org Geochem 1982, 4: 63–77. 10.1016/0146-6380(82)90009-2

Sasa K, Takahashi T, Tosaki Y, Matsushi Y, Sueki K, Tamari M, Amano T, Oki T, Mihara S, Yamato Y, Nagashima Y, Bessho K, Kinoshita N, Matsumura H: Status and research programs of the multinuclide accelerator mass spectrometry system at the University of Tsukuba. Nucl Instr Meth Phys Res B 2010, 268: 871–875. 10.1016/j.nimb.2009.10.052

Sato T, Kazahaya K, Yasuhara M, Itoh J, Takahashi HA, Morikawa N, Takahashi M, Inamura A, Handa H, Matsumoto N: Hydrological changes due to the M7.0 earthquake at Iwaki, Fukushima induced by the 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake, Japan. In American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting. San Francisco: The Moscone Center; 2011. 5–9 December 2011 5–9 December 2011

Sato H, Ishiyama T, Kato N, Higashinaka M, Kurashimo E, Iwasaki T, Abe S: An active footwall shortcut thrust revealed by seismic reflection profiling: a case study of the Futaba fault, northern Honshu, Japan. EGU General Assembly, Austria Center, Vienna; 2013. 07–12 April 2013 07–12 April 2013

Sharma P, Bourgeois M, Elmore D, Granger D, Lipschutz ME, Ma X, Miller T, Mueller K, Rickey F, Simms P, Vogt S: PRIME lab AMS performance, upgrades and research applications. Nucl Instrum Meth Phys Res B 2000, 172: 112–123. 10.1016/S0168-583X(00)00132-4

Shibata T, Nakamura E: Across-arc variations of isotope and trace element compositions from quaternary basaltic volcanic rocks in northeastern Japan: implications for interaction between subducted oceanic slab and mantle wedge. J Geophys Res 1997, 102: 8051–8064. 10.1029/96JB03661

Shipboard Scientific Party: DSDP volume LVI and LVII table of contents. site 436, Japan Trench Outer Rise, leg 56 1980. doi:10.2973/dsdp.proc.5657.107.1980 doi:10.2973/dsdp.proc.5657.107.1980

Sibson RH: Implications of fault-valve behaviour for rupture nucleation and recurrence. Tectonophysics 1992, 211: 283–293. 10.1016/0040-1951(92)90065-E

Sibson RH: Stress switching in subduction forearcs: implications for overpressure containment and strength cycling on megathrusts. Tectonophysics 2013, 600: 142–152.

Snyder GT, Fabryka-Martin JT: 129I and 36Cl in dilute hydrocarbon waters: marine-cosmogenic, in situ, and anthropogenic sources. Appl Geochem 2007, 22: 692–714. 10.1016/j.apgeochem.2006.12.011

Snyder G, Fehn U: Global distribution of 129I in rivers and lakes: implications for iodine cycling in surface reservoirs. Nucl Instrum Meth Phys Res B 2004, 223–224: 579–586.

Tagami K, Uchida S: Concentrations of chlorine, bromine and iodine in Japanese rivers. Chemosphere 2006, 65: 2358–2365. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.04.077

Takahashi M, Kazahaya K, Yasuhara M, Takahashi HA, Morikawa N, Inamura A: Geochemical study of hot spring waters in Abukuma area, northeast Japan. J Jpn Assoc Hydrol Sci 2004, 34: 227–244. [in Japanese with English abstract] [in Japanese with English abstract]

Tanaka A, Yano Y, Sasada M, Yamano M: Geothermal gradient and heat flow data in and around Japan. Geological Survey of Japan (CD-ROM database). 2004.

The Research Group for Active Faults of Japan: Active faults in Japan (Sheet Maps and Inventories), revised edn. University of Tokyo Press, Tokyo; 1991:163.

Toda S, Tsutsumi H: Simultaneous reactivation of two, subparallel, inland normal faults during the Mw 6.6 11 April 2011 Iwaki earthquake triggered by the Mw 9.0 Tohoku-oki, Japan, earthquake. Bull Seismol Soc Am 2013, 103: 1584–1602. 10.1785/0120120281

Tokyo Electric Power Company: Fukushima First and Second Nuclear Power Plants; geology and geological structures of the power plant sites. Tokyo Electric Power Company,; 2012. Accessed 30 Apr 2014 [in Japanese] http://www.tepco.co.jp/cc/direct/images/120810d.pdf Accessed 30 Apr 2014 [in Japanese]

Tomaru H, Ohsawa S, Amita K, Lu Z, Fehn U: Influence of subduction zone settings on the origin of forearc fluids: halogen concentrations and 129I/I ratios in waters from Kyushu, Japan. Appl Geochem 2007, 22: 676–691. 10.1016/j.apgeochem.2006.12.014

Tomaru H, Lu Z, Fehn U, Muramatsu Y, Matsumoto R: Age variation of pore water iodine in the eastern Nankai Trough, Japan: evidence for different methane sources in a large gas hydrate field. Geology 2007, 35: 1015–1018. 10.1130/G24198A.1

Tomaru H, Lu Z, Snyder GT, Fehn U, Hiruta A, Matsumoto R: Origin and age of pore waters in an actively venting gas hydrate field near Sado Island, Japan Sea: interpretation of halogen and 129I distributions. Chem Geol 2007, 236: 350–366. 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2006.10.008

Tomaru H, Fehn U, Lu Z, Takeuchi R, Inagaki F, Imachi H, Kotani R, Matsumoto R, Aoike K: Dating of dissolved iodine in pore waters from the gas hydrate occurrence offshore Shimokita Peninsula, Japan: 129I results from the D/V Chikyu shakedown cruise. Resour Geol 2009, 59: 359–373. 10.1111/j.1751-3928.2009.00103.x

Tomaru H, Lu Z, Fehn U, Muramatsu Y: Origin of hydrocarbons in the Green Tuff region of Japan: 129I results from oil field brines and hot springs in the Akita and Niigata Basins. Chem Geol 2009, 264: 221–231. 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2009.03.008

Tomita T, Ohtani T, Shigematsu N, Tanaka H, Fujimoto K, Kobayashi Y, Miyashita Y, Omura K: Development of the Hatagawa Fault Zone clarified by geological and geochronological studies. Earth Planets Space 2002, 54: 1095–1102. 10.1186/BF03353308

Tosaki Y, Tase N, Kondoh A, Sasa K, Takahashi T, Nagashima Y: Distribution of 36Cl in the Yoro River basin, central Japan, and its relation to the residence time of the regional groundwater flow system. Water 2011, 3: 64–78. 10.3390/w3010064

Tsuru T, Park J-O, Miura S, Kodaira S, Kido Y, Hayashi T: Along-arc structural variation of the plate boundary at the Japan Trench margin: implication of interplate coupling. J Geophys Res 2002, 107(B12):2357. doi:10.1029/2001JB001664 doi:10.1029/2001JB001664

Uehara S, Shimamoto T: Gas permeability evolution of cataclasite and fault gouge in triaxial compression and implications for changes in fault-zone permeability structure through the earthquake cycle. Tectonophysics 2004, 378: 183–195. 10.1016/j.tecto.2003.09.007

von Huene R, Culotta R: Tectonic erosion at the front of the Japan Trench convergent margin. Tectonophysics 1989, 160: 75–90. 10.1016/0040-1951(89)90385-5

von Huene R, Lallemand S: Tectonic erosion along the Japan and Peru convergent margins. Geol Soc Am Bull 1990, 102: 704–720. 10.1130/0016-7606(1990)102<0704:TEATJA>2.3.CO;2

Yanagisawa Y, Nakamura K, Suzuki Y, Sawamura K, Yoshida F, Tanaka Y, Honda Y, Tanahashi M: Tertiary biostratigraphy and subsurface geology of the Futaba district, Joban Coalfield, northeast Japan. Bull Geol Surv Japan 1989, 40(8):405–467. [in Japanese with English abstract] [in Japanese with English abstract]

Yoshii T: Proposal of the “aseismic front”. Zisin 1975, 2(28):365–367. [in Japanese] [in Japanese]

Yoshii T: A detailed cross-section of the deep seismic zone beneath northeastern Honshu, Japan. Techtonophysics 1979, 55: 349–360. 10.1016/0040-1951(79)90183-5

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas, specifically, ‘Geofluids: Nature and dynamics of fluids in subduction zones’ from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan (No. 24109706). The authors sincerely thank K. Sasa and T. Takahashi (University of Tsukuba Tandem Accelerator Complex) for measuring 36Cl/Cl.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YST carried out the measurements of iodine concentrations and 129I/I ratios and drafted the initial manuscript. KK coordinated the present work and helped YST to complete the manuscript. YT and NM determined 36Cl/Cl, HM performed the AMS measurements, MT carried out the ion chromatography and stable isotope analyses, and TS participated in the groundwater sampling. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

40623_2013_121_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Additional file 1: Table S1: Major and trace element compositions of representative rock samples. Data for rocks similar to the host rocks of our sampling locations were selected from the original data reported in Morikawa and Tosaki (2013). (PDF 516 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Togo, Y.S., Kazahaya, K., Tosaki, Y. et al. Groundwater, possibly originated from subducted sediments, in Joban and Hamadori areas, southern Tohoku, Japan. Earth Planet Sp 66, 131 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1880-5981-66-131

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1880-5981-66-131