Abstract

Endogenous endophthalmitis (EE) is a rare but devastating infection that occurs secondary to seeding of the intraocular cavity from an extraocular focus. Recent reports suggest the increasing prevalence and incidence of Klebsiella pneumoniae as a causative organism in Asian countries. Analysis of the largest cohorts published to date suggests that K. pneumoniae endogenous endophthalmitis (KPEE) is 10 to 15 times more prevalent than other causes of EE. The incidence of KPEE among patients with systemic Klebsiella infection appears to be >100-fold more common than other causes of EE. The exact reason for these observations is not clear, but a number of studies now suggest that Klebsiella serotypes K1 and K2 have virulence factors that enhance their survival in diabetic patients and increase their pathogenicity. Here, we report two cases of KPEE in the USA. We also review the recent clinical and basic science literature on the prevalence, incidence, and pathophysiology of this emerging and devastating infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Review

Introduction

Endogenous endophthalmitis (EE) is a relatively uncommon but severe infection that comprises 2% to 15% of all cases of endophthalmitis [1–3]. It is commonly associated with underlying immunosuppression including diabetes mellitus, cardiac disease, renal insufficiency and malignancy. While a number of organisms have been implicated in EE, Klebsiella pneumoniae has been recognized as an increasingly prevalent cause of EE in the Asian population [1, 2, 4–12]. In addition to numerous case series from Asia, a growing body of basic scientific research has begun to elucidate the pathophysiology of this particular infection. In this case series and review, we report two cases of systemic Klebsiella infection that resulted in EE within the USA. We also discuss recent literature that is starting to shed light on the epidemiology and pathophysiology of this condition.

Epidemiology

The clinical experience with K. pneumoniae endogenous endophthalmitis (KPEE) is varied, and comparison of the numerous retrospective studies is difficult due to differences in the methods and reporting criteria [1]. Nevertheless, several large retrospective studies report a surprisingly high number of cases of KPEE among patients with EE (Table 1). Wong et al. reported a series of 27 patients with bacterial EE from Singapore over a 4-year period [6]. Sixty percent of cases were secondary to K. pneumoniae, and 48% of these had hepatobiliary sources of infection. Chen et al. reported 74 patients with EE from Taiwan over a 10-year period [5]. Sixty-one percent of cases were secondary to K. pneumoniae, and 53% of these cases had liver abscess. Ang et al. reported 113 patients with EE from Singapore over a 21-year period [9]. Sixty-one patients (54%) and 71 eyes had KPEE. These studies demonstrate that among patients with EE in Asia, the prevalence of KPEE is high (54% to 61%; Table 1). In contrast, Jackson et al. reported a series of 21 eyes in 19 patients with EE from England over a 17-year period, and only one case was secondary to Klebsiella (5% prevalence) [1]. Similarly, Okada et al. reviewed all cases of EE admitted to the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary and Massachusetts General Hospital over a 10-year period. They found 28 patients with the diagnosis of EE, and only one case was due to Klebsiella (prevalence 3.6%) [3]. Table 1 summarizes these studies.

The reason for this high prevalence in Asia is not clear. Some data suggest that Asian populations have a high prevalence of Klebsiella bacteremia and that K. pneumoniae is particularly more likely to cause EE than other organisms. Sheu et al. reported a series from Taiwan of 602 patients admitted with K. pneumoniae liver abscess over an 18-year period [13]. Forty-two patients (7%) and 53 eyes developed KPEE. Fifty-three percent of these patients had diabetes. Sng et al. reported a case-controlled study of 133 patients with Klebsiella bacteremia from Singapore over a 1-year period [4]. KPEE was reported in five (3.8%) of these patients, and two cases were bilateral. All cases with KPEE were associated with liver abscess. Yang et al. reported a series of 200 patients with K. pneumoniae liver abscess admitted to a Taiwanese hospital over a 17-year period [14]. Twenty-seven eyes of 22 patients (11%) developed KPEE, and 68% of these had diabetes mellitus. These studies suggest that the incidence of KPEE among patients with systemic Klebsiella infection is 3% to 11% (Table 2). This rate of ocular involvement among patients with systemic Klebsiella infection is much higher than ocular involvement in other systemic infections. For example, Jackson et al. reviewed 5,859 cases of all-cause bacteremia at St. Thomas Hospital (England) and reported EE in 19 patients (incidence of <0.01%) [1]. Table 2 summarizes these data.

The incidence and prevalence calculations above suggest that KPEE warrants further investigation. In fact, a number of studies have specifically looked at the pathophysiology of this particular infection. The findings have been revealing about the mechanisms of infection as well as the particularly poor prognosis of this infection versus other causes of endophthalmitis.

Clinical experience

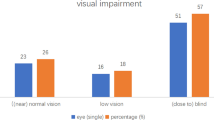

The classic features of EE include ocular pain, blurred vision, swollen eyelids, injection and chemosis, anterior chamber inflammation, hypopyon, and elevated intraocular pressure. Systemic disease is often advanced, and patients are usually already hospitalized for bacteremia, sepsis, or other systemic complications before the onset of ocular symptoms. There is no consensus on treatment although most studies suggest early and aggressive intervention. A number of studies have reported the visual outcome of KPEE after treatment. Unfortunately, almost all large series and most case reports have very poor outcomes. One case report [15] and one series [16] suggest that very early vitrectomy can preserve vision, but most studies report very poor outcomes regardless of specific interventions.

For example, Yang et al. reviewed the risk factors, clinical features, and visual outcomes in patients with KPEE associated with K. pneumoniae liver abscess. Among the 200 patients with K. pneumoniae liver abscess, 22 consecutive patients with KPEE were reported during an 8-year period. Twenty-three percent of patients had bilateral involvement, and 68% of these had diabetes. Despite aggressive treatment, final visual acuity of light perception or worse occurred in 89% of patients of which 41% were eventually eviscerated or enucleated [14].

Similarly, Yoon et al. reviewed seven cases of KPEE. Five patients (71%) had diabetes, and four patients (57%) had liver abscess. Eight percent of eyes had hand-motion vision or worse on presentation. After aggressive treatment including pars plana vitrectomy, 70% of eyes had count fingers vision or worse. However, three eyes had vision better than count fingers, and in all eyes, the retina remained attached throughout 6 months of follow-up [16].

We have previously described an atypical case of KPEE [26] that presented with bilateral intraocular inflammation without hypopyon, and systemic evaluation revealed a widely disseminated infection. In the next subsections, we summarize our experience with two additional cases of KPEE with interesting atypical features that merit attention.

Atypical case report 1

A 54-year-old Vietnamese man was referred with pain in the right eye. There was no history of trauma or surgery. He had undergone vitreous tap and injection at an outside facility for presumed endophthalmitis. The patient’s past medical history was significant for hypertension. Visual acuity was counting fingers in the right eye and 20/25 in the left eye. There was less than 1 mm of hypopyon in the right eye and dense vitritis. The patient was admitted for presumed EE and underwent immediate vitrectomy. In addition to vitreous inflammation, the superior temporal retina was necrotic. The quadrant of retinitis was demarcated with laser, and intravitreal vancomycin and ceftazidime were administered. Cultures of aspirated vitreous debris grew K. pneumoniae. Systemic evaluation revealed K. pneumoniae liver abscess. The patient responded well to systemic and ocular therapies. Although this case had a typical presentation and course, it is remarkable in that the final visual acuity in the right eye was 20/30. There are very few reports of such good outcomes associated with KPEE, and to date, the reasons for these outcomes are not clear.

Atypical case report 2

A 47-year-old Hispanic man originally from Mexico was referred for evaluation of uveitis of unknown cause. The patient had been living in Los Angeles for the past 24 years. The patient experienced fever and chills 3 weeks prior and subsequently noticed blurry vision in his left eye 2 weeks prior to presentation. The patient denied any previous ocular disease or trauma. The patient was seen by an outside physician and started on oral Bactrim for presumed prostatitis shortly after the onset of his systemic symptoms. The patient was also seen by an ophthalmologist and started on atropine twice a day OS, prednisolone acetate every hour OS, and oral prednisone 30 mg/day for presumed uveitis. Review of systems was significant for 20- to 30-lb weight loss in the month preceding presentation. The patient’s past medical history was notable for hypertension. The patient denied any drug use, smoking, or travel besides a recent trip to Texas, Arizona, and Mexico.

Visual acuity was 20/80 in the right eye and hand motion in the left eye. Intraocular pressures were normal. Examination of the right eye was unremarkable for any acute process. The left eye demonstrated mild conjunctival injection and chemosis, and a 1.5-mm layered hypopyon. Pigmented debris was noted on the anterior lens capsule. The left fundus revealed moderate vitreous haze, some layered vitreous debris inferiorly and multiple large, white retinal lesions involving the macula. This case was remarkable in that ultrasound revealed a subretinal abscess with vitreous strands and debris.

The patient was diagnosed with EE secondary to presumed UTI and he received intravitreal tap and injection of vancomycin, ceftazidime, and voriconazole. He was tapered off the oral steroids and admitted for immediate systemic treatment. Serum glucose levels were elevated (322 mg/dL) as was the hemoglobin A1c (8.7). Other labs were significant including elevated WBC (12.6), elevated CRP (2.5), positive MHA-TP, negative RPR, and negative human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). He was started on intravenous vancomycin and ceftazidime. The patient underwent pars plana vitrectomy and lensectomy with drainage of subretinal abscess. Material from the vitreous and subretinal abscess grew K. pneumoniae. Urine culture was positive for K. pneumoniae. The patient was discharged on home IV ceftriaxone, oral metronidazole, and oral levofloxacin for 4 to 6 weeks. The left eye ultimately developed light perception vision and a total retinal detachment. While this case has a typical course and outcome for KPEE, it is unusual in that the infection involved a subretinal abscess.

Pathophysiology

It is well known that patients with EE usually have comorbid immunocompromising diseases such as diabetes, HIV infection, indwelling catheters, renal failure, cardiac disease, malignancy, or immunosuppressive therapy. KPEE occurs secondary to hematogenous dissemination from an extraocular focus (usually liver) and is rarely associated with surgery or trauma. The ‘Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study’ reported that only 5.9% of culture-positive cases were due to gram-negative organisms, and none were due to Klebsiella [17]. Only one case series that we could find reported Klebsiella endophthalmitis secondary to cataract surgery, trauma, or other causes [18].

In addition to host immunosuppression, Klebsiella-specific virulence factors have been implicated in the pathogenicity of this organism. K. pneumoniae is an enteric, gram-negative bacillus with a polysaccharide capsule. The composition of the cell surface antigens on the capsule are used to classify Klebsiella organisms into serotypes. Organisms with capsule serotype K1 or K2 seem to predominate in cases of liver abscess and metastatic spread to other organs including the eye [19, 20]. Of the several serotypes (K1, K2, K5, K20, K54, K57, among others) that have been identified, multiple lines of evidence support the increased virulence of organisms with K1 or K2 serotypes. For example, capsular serotypes K1 and K2 inhibit phagocytosis by neutrophils isolated from diabetic patients in vitro [21]. In addition, K1 isolates show significantly higher serum resistance and decreased susceptibility to intracellular destruction by neutrophils than other Klebsiella serotypes [20]. A single intraperitoneal injection of human neutrophils containing phagocytosed K1 K. pneumoniae leads to abscess formation in multiple sites in mice, whereas non-K1 serotypes do not demonstrate this ability [20]. This suggests that there may be a role for capsular phenotype testing in patients with Klebsiella bacteremia. Currently, capsular phenotyping is available in the USA, but it is not commonly performed [22–25]. We recently reported one case of bilateral KPEE with widespread disseminated systemic infection with confirmed K1 capsular serotype in the USA (see the ‘Clinical experience’ section) [26]. To our knowledge, no other cases of Klebsiella endophthalmitis with verified K1 serotype have been reported in the USA.

The K1 and K2 serotypes are associated with genotypes which may confer some of their virulence. Specifically, the magA gene (mucoviscosity-associated gene A or capsular polymerase Wzy(KpK1) [27]) and rmpA gene (regulator of the mucoid phenotype) have been found in the K1 and K1/K2 serotypes, respectively [28]. The specific roles of these genes in the pathophysiology of endophthalmitis has yet to be determined, but a recent study in mice showed that the hypermucoviscous K. pneumoniae associated with the K1 serotype is associated with more rapid development of phthisis, more pronounced inflammation, and poor recovery of retinal function compared with a control strain [28]. A recent study demonstrates that wild-type magA+ and trans-complemented magA organisms grow more rapidly and cause a more profound decrease in ERG a- and b-waves and cellular infiltration in a mouse model than the magA deficient organism [29]. This study is notable in that the organisms lack any hemolytic or proteolytic toxins [29]. Interestingly, wild-type K. pneumoniae (magA+) causes a more inflammatory response (as measured by myeloperoxidase assay) than trans-complemented magA organisms, suggesting additional virulence factors in the wild-type organisms or a pathologic difference in the trans-complemented organism [29]. Analysis of various growth media conditioned by K. pneumoniae seems to suggest that a secreted factor(s) may also be involved in Klebsiella virulence [11, 30]. Systemically, the lethal dose of magA-positive strains in a mouse model was approximately 4 to 5 log units lower than isogenic mutants deficient for magA [19, 31, 32]. Clinically, both the K1 and K2 serotypes have been associated with a hypermucoviscous (HMV) phenotype. This phenotype is defined by the formation of a mucoviscous string greater than 5 mm when a standard bacteriological loop is passed through a colony [28]. It appears that the HMV phenotype overlaps with the K1/K2 serotypes and is significantly associated with bacteremia and invasive infections including meningitis and endophthalmitis [33]. The risk for metastatic spread to the eye or the CNS with primary Klebsiella abscess is noted to be 3% to 10% [34, 35]; however, at least 50% of patients with Klebsiella endophthalmitis have an underlying liver abscess caused by the same bacteria [1]. The poor response of KPEE to aggressive treatment is not well understood. Some evidence suggest that this may be due to poor surveillance and late diagnosis [9]. For example, our previously published case report [26] as well as a few other studies have noted disseminated systemic infection within the first few days of presentation [13, 36]. This suggests that widespread infection was already present before ocular involvement in at least some cases. Other factors may include antimicrobial resistance. K. pneumoniae is well known for its resistance to traditional and novel antibacterial agents including third-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, carbapenems, and extended spectrum beta-lactamases.

Conclusions

The notably high incidence and prevalence of KPEE in Asia has resulted in a number of informative studies reviewed above. The high incidence of KPEE in patients with systemic K. pneumoniae infection may provide a model of EE which can facilitate further clinical studies of this infection. These studies in conjunction with basic science studies of the pathophysiology of K. pneumoniae infection are allowing focused hypothesis testing of the mechanism of EE. Therefore, further study of KPEE may facilitate better diagnostic and therapeutic management of endophthalmitis in general.

The data available suggest that patients with liver abscess and immunocompromising conditions should be watched closely for signs and symptoms of hematologic spread and EE. These studies suggest a causal and particularly prevalent relationship between systemic Klebsiella infection and KPEE. Serotyping for the K1/K2-positive organisms may play an increasing role in determining which patients are at highest risk. This information can potentially lead to screening guidelines or prophylactic treatment. Patients of Asian descent are at highest risk for Klebsiella-related EE. However, it is not clear if this is due to a genetic predisposition to infection among Asians or a higher prevalence of virulent Klebsiella organisms in Asia. The studies reviewed here suggest the latter possibility since the polysaccharide capsule is protective against phagocytosis and bactericidal serum factors. This report also highlights the occurrence of KPEE in the USA in patients with no known recent travel history to Asia. No course of treatment has been clearly beneficial, but a few cases where immediate, early treatment (within 24 h of presentation) with pars plana vitrectomy and/or intravitreal antibiotics was performed preserved some degree of useful vision [15].

References

Jackson TL, Eykyn SJ, Graham EM, Stanford MR: Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis: a 17-year prospective series and review of 267 reported cases. Surv Ophthalmol 2003,48(4):403–423. 10.1016/S0039-6257(03)00054-7

Connell PP, O’Neill EC, Fabinyi D, Islam FMA, Buttery R, McCombe M, Essex RW, Roufail E, Clark B, Chiu D, Campbell W, Allen P: Endogenous endophthalmitis: 10-year experience at a tertiary referral centre. Eye (Lond) 2011,25(1):66–72. 10.1038/eye.2010.145

Okada AA, Johnson RP, Liles WC, D’Amico DJ, Baker AS: Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis. Report of a ten-year retrospective study. Ophthalmology 1994,101(5):832–838.

Sng CC, Jap A, Chan YH, Chee SP: Risk factors for endogenous Klebsiella endophthalmitis in patients with Klebsiella bacteraemia: a case–control study. Br J Ophthalmol 2008,92(5):673–677. 10.1136/bjo.2007.132522

Chen YJ, Kuo HK, Wu PC, Kuo ML, Tsai HH, Liu CC, Chen CH: A 10-year comparison of endogenous endophthalmitis outcomes: an east Asian experience with Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. Retina 2004,24(3):383–390. 10.1097/00006982-200406000-00008

Wong JS, Chan TK, Lee HM, Chee SP: Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis: an East Asian experience and a reappraisal of a severe ocular affliction. Ophthalmology 2000,107(8):1483–1491. 10.1016/S0161-6420(00)00216-5

Al-Mahmood AM, Al-Binali GY, Alkatan H, Abboud EB, Abu El-Asrar AM: Endogenous endophthalmitis associated with liver abscess caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae. Int Ophthalmol 2011,31(2):145–148. 10.1007/s10792-011-9429-9

Dehghani AR, Masjedi A, Fazel F, Ghanbari H, Akhlaghi M, Karbasi N: Endogenous Klebsiella endophthalmitis associated with liver abscess: first case report from Iran. Case Report Ophthalmol 2011,2(1):10–14. 10.1159/000323449

Ang M, Jap A, Chee SP: Prognostic factors and outcomes in endogenous Klebsiella pneumoniae endophthalmitis. Am J Ophthalmol 2011,151(2):338–344 e2. 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.08.036

Chung KS, Kim YK, Song YG, Kim CO, Han SH, Chin BS, Gu NS, Jeong SJ, Baek JH, Choi JY, Kim HY, Kim JM: Clinical review of endogenous endophthalmitis in Korea: a 14-year review of culture positive cases of two large hospitals. Yonsei Med J 2011,52(4):630–634. 10.3349/ymj.2011.52.4.630

Pomakova DK, Hsiao CB, Beanan JM, Olson R, MacDonald U, Keynan Y, Russo TA: Clinical and phenotypic differences between classic and hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumonia: an emerging and under-recognized pathogenic variant. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2012,31(6):981–989. 10.1007/s10096-011-1396-6

Keynan Y, Rubinstein E: Endogenous endophthalmitis caused by hypermucoviscous Klebsiella pneumoniae: an emerging disease in Southeast Asia and beyond. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2008,10(5):343–345. 10.1007/s11908-008-0055-2

Sheu SJ, Kung YH, Wu TT, Chang FP, Horng YH: Risk factors for endogenous endophthalmitis secondary to Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: 20-year experience in Southern Taiwan. Retina 2011,31(10):2026–2031. 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31820d3f9e

Yang CS, Tsai HY, Sung CS, Lin KH, Lee FL, Hsu WM: Endogenous Klebsiella endophthalmitis associated with pyogenic liver abscess. Ophthalmology 2007,114(5):876–880. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.12.035

Ishii K, Hiraoka T, Kaji Y, Sakata N, Motoyama Y, Oshika T: Successful treatment of endogenous Klebsiella pneumoniae endophthalmitis: a case report. Int Ophthalmol 2011,31(1):29–31. 10.1007/s10792-010-9387-7

Yoon YH, Lee SU, Sohn JH, Lee SE: Result of early vitrectomy for endogenous Klebsiella pneumoniae endophthalmitis. Retina 2003,23(3):366–370. 10.1097/00006982-200306000-00013

Forster RK: The endophthalmitis vitrectomy study. Arch Ophthalmol 1995,113(12):1555–1557. 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100120085015

Scott IU, Matharoo N, Flynn HW Jr, Miller D: Endophthalmitis caused by Klebsiella species. Am J Ophthalmol 2004,138(4):662–663. 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.04.051

Fang CT, Lai SY, Yi WC, Hsueh PR, Liu KL, Chang SC: Klebsiella pneumoniae genotype K1: an emerging pathogen that causes septic ocular or central nervous system complications from pyogenic liver abscess. Clin Infect Dis 2007,45(3):284–293. 10.1086/519262

Lin JC, Chang FY, Fung CP, Yeh KM, Chen CT, Tsai YK, Siu LK: Do neutrophils play a role in establishing liver abscesses and distant metastases caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae? PLoS One 2010,5(11):e15005. 10.1371/journal.pone.0015005

Lin JC, Siu LK, Fung CP, Tsou HH, Wang JJ, Chen CT, Wang SC, Chang FY: Impaired phagocytosis of capsular serotypes K1 or K2 Klebsiella pneumoniae in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with poor glycemic control. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006,91(8):3084–3087. 10.1210/jc.2005-2749

Karama EM, Willermain F, Janssens X, Claus M, Van den Wijngaert S, Wang JT, Verougstraete C, Caspers L: Endogenous endophthalmitis complicating Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess in Europe: case report. Int Ophthalmol 2008,28(2):111–113. 10.1007/s10792-007-9111-4

Harris EW, D’Amico DJ, Bhisitkul R, Priebe GP, Petersen R: Bacterial subretinal abscess: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Ophthalmol 2000,129(6):778–785. 10.1016/S0002-9394(00)00355-X

Saccente M: Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess, endophthalmitis, and meningitis in a man with newly recognized diabetes mellitus. Clin Infect Dis 1999,29(6):1570–1571. 10.1086/313539

Margo CE, Mames RN, Guy JR: Endogenous Klebsiella endophthalmitis. Report of two cases and review of the literature. Ophthalmology 1994,101(7):1298–1301.

Kashani AH, Eliott D: Bilateral Klebsiella pneumoniae (K1 Serotype) endogenous endophthalmitis as the presenting sign of disseminated infection. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging 2011, 42: e12-e14. 10.3928/15428877-20100929-08

Yeh KM, Lin JC, Yin FY, Fung CP, Hung HC, Siu LK, Chang FY: Revisiting the importance of virulence determinant magA and its surrounding genes in Klebsiella pneumoniae causing pyogenic liver abscesses: exact role in serotype K1 capsule formation. J Infect Dis 2010,201(8):1259–1267. 10.1086/606010

Wiskur BJ, Hunt JJ, Callegan MC: Hypermucoviscosity as a virulence factor in experimental Klebsiella pneumoniae endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2008,49(11):4931–4938. 10.1167/iovs.08-2276

Hunt JJ, Wang JT, Callegan MC: Contribution of mucoviscosity-associated gene A (magA) to virulence in experimental Klebsiella pneumoniae endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011,52(9):6860–6866. 10.1167/iovs.11-7798

Russo TA, Shon AS, Beanan JM, Olson R, MacDonald U, Pomakov AO, Visitacion MP: Hypervirulent K. pneumoniae secretes more and more active iron-acquisition molecules than “classical” K. pneumoniae thereby enhancing its virulence. PLoS One 2011,6(10):e26734. 10.1371/journal.pone.0026734

Fang CT, Lai SY, Yi WC, Hsueh PR, Liu KL: The function of wzy_K1 (magA), the serotype K1 polymerase gene in Klebsiella pneumoniae cps gene cluster. J Infect Dis 2010,201(8):1268–1269. 10.1086/652183

Fang CT, Chuang YP, Shun CT, Chang SC, Wang JT: A novel virulence gene in Klebsiella pneumoniae strains causing primary liver abscess and septic metastatic complications. J Exp Med 2004,199(5):697–705. 10.1084/jem.20030857

Lee HC, Chuang YC, Yu WL, Lee NY, Chang CM, Ko NY, Wang LR, Ko WC: Clinical implications of hypermucoviscosity phenotype in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates: association with invasive syndrome in patients with community-acquired bacteraemia. J Intern Med 2006,259(6):606–614. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01641.x

Chiu YT, Tsai YY, Lin JM, Hung PT: Septic metastatic endophthalmitis complicating Klebsiella pneumoniae scalp furuncle. Eye (Lond) 2007,21(1):142–144. 10.1038/sj.eye.6702470

Cheng DL, Liu YC, Yen MY, Liu CY, Wang RS: Septic metastatic lesions of pyogenic liver abscess. Their association with Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia in diabetic patients. Arch Intern Med 1991,151(8):1557–1559. 10.1001/archinte.1991.00400080059010

Lee SS, Chen YS, Tsai HC, Wann SR, Lin HH, Huang CK, Liu YC: Predictors of septic metastatic infection and mortality among patients with Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess. Clin Infect Dis 2008,47(5):642–650. 10.1086/590932

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AHK wrote the original manuscript. Both AHK and DE collected data, reviewed the manuscript for corrections/revisions, and contributed significantly to the final product. Both authors revised the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kashani, A.H., Eliott, D. The emergence of Klebsiella pneumoniae endogenous endophthalmitis in the USA: basic and clinical advances. J Ophthal Inflamm Infect 3, 28 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1869-5760-3-28

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1869-5760-3-28