Abstract

Background

The study deals with the characteristics of temperament of preterm infants during their preschool age in order to not only investigate likely "difficult or problematic profiles", guided by impairments driven by their preterm birth, but also to provide guidelines for the activation of interventions of prevention, functional to improve the quality of preterm infant's life.

Methods

The study involved a group of 105 children where 50 preterm children at the average age of 5 years and 2 months, enrolled in preschools of Palermo. The research planned the child reference teachers to be administered a specific questionnaire, the QUIT, made up of 60 items investigating six specific typical dimensions of temperament (Motor control activity - related to the ability of practicing motor control activity; Attention - related to the ability of guiding and keeping the focus of attention on a certain stimulus; Inhibition to novelty - regarding with emotional reactivity in front of environmental stimuli; Social orientation - meant in terms of attention and interest towards social stimuli; Positive and negative emotionality - regarding the tendency to mainly express positive or negative emotions.

Results

The results show in general how preschool-aged preterm infants, identified by such a study, compared with full-term children, are characterized by "normal" temperament based on a strong inclination and orientation in mainly expressing positive feelings. Yet, an impairment of the areas most relating to attention and motor control activity seems to emerge.

Conclusions

The data suggest specific interventions for preterm infant development and their reference systems and, at the same time, can guide paediatrician and neonatologist dealing with preterm infants, in focalizing and monitoring, even since health status assessments, specific areas of development that, since preschool age, can highlight the presence of real forerunners of maladjustments and likely configurations of cognitive, emotional or behaviour disadaptive functioning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Premature birth is an evolutional risk condition for children at their birth, for their survival and initial characteristics of their neonatal development (organic-functional immaturity due to gestation age - < 32 weeks, birth weight < 2000 gr., neurocognitive complications, heart and breath difficulties, muscle hypotony, poor reflexivity, etc.), and, mainly, for their entire evolutional course that it often seems to take shape even since his/her early childhood, in terms of behaviour, cognitive, social and motor control impairments [1–3]. Several studies, in fact, highlight how preterm infants, more frequently than full-term children do, show problematic evolutional outcomes that are often displayed at preschool and school age only. They are related with cognitive area (sensorial deficit, language impairments, learning difficulty, etc), emotional area (that is more specifically, impairments in regulation of emotions and impulses), and relational area (behaviour problems and of adjustment in social relationships with their peer group and adults) [4–11].

This study, just referring such a heuristic picture, following the Paediatric Psychology perspective [12–15], focuses its attention on some development areas of preschool-aged preterm infants. In particular, it studies the characteristics of their temperament [16–18], investigating likely "difficult or problematic profiles", guided by the impairments brought by their preterm birth and social and individual factors that interact with it, and providing guidelines to activate prevention interventions functional to the improvement of quality of life of preterm infants. They are typologies of information suggesting reference paediatricians the focuses of intervention and monitoring during health status assessments.

Therefore it can be mainly focalized specific areas of motor control development (movement coordination) or cognitive (attentive and regulative processes) or emotional (expression and modulation of emotions) that highlight, even since preschool age, the presence of real precursors of future maladjustments and likely disadaptive configurations of cognitive, emotional, maladjustment or behaviour functions [9–11].

In particular, the study model of reading the temperament is in terms of goodness of fit between individual and environment, meant as a variable moderating the reciprocal adjustment between child and environment [19–21] and referring to a series of cognitive, emotional and relational processes. Motor control activity, Attention, Inhibition to novelty, Social orientation and Emotionality are the model areas. Each of them is considered with a specific meaning.

The Motor control activity can be meant as the vigour of movement and modulation of motor control activity - the lack of such processes in preterm infants seems to guide some impairments on motor control development especially in relation to their capacity of modulating the "end" movement and visuospatial coordination [3].

The Attention area is meant in terms of orientation, regulation and attention persistency, that are all processes considered, in preterm infants, little relevant by literature, at the early phases of their life mainly. Preterm infants seem to be more distractible and less able in passing and linking an emotional internal phase to an external one, monitoring what happens or their own action [22], as well as they prove to be less able to keep attention focus on an object, or on what they are doing. Such unsteadiness does not seem to allow preterm infants to activate a series of mechanisms and other cognitive processes (collecting and selecting information, concentration, etc.) functional to a more rational adjustment to situations.

As for the Inhibition to novelty, the model refers to emotional reactivity introducing an adjustment to social context [2], under studies underlying that in preterm infants there is often a higher reactivity to external and internal stimuli than full-term children.

The Social orientation area is meant as emotional answers in front of unknown people and attention/interest towards social stimuli. Preterm infants seem to approach what is new with a greater self-confidence than full-term children do, and show a good involvement and openness towards interpersonal relationships [17].

Finally, in relation with Emotionality area, the model focalizes the predominance of negative and positive emotions referring to preterm infants' higher predisposition and orientation toward expressing positive emotions [17].

Furthermore, the model states that such areas give life to profiles that, more or less characterized by the impairment of certain processes [23–26, 17], evolve during their development, up to reduce likely differences between preterm and full-term children. Therefore, from a social view of preterm infants as "difficult-temperament" children [19], a view based on "easiness", sociability and patience was reached [27–29, 18].

Considering the cultural contextualization of such studies (Australia, England, U.S.A., etc.), this study is aimed to verify the likely overlapping of data and then, their cross-cultural validity.

Methods

Objectives and hypothesis

In light of the last considerations and in function of the above described model, the study has the following goals:

-

Investigating the characteristics of temperament areas of preschool-aged preterm infants

-

Investigating the temperament profile (emotive, calm, normal, difficult) of preschool-aged preterm infants

Considering such aims, research hypothesis are to be found in:

-

Verifying the existence of statistically significant differences between preterm infants and full-term children, with regard to the different areas defining temperament (Motor control activity, Attention, Inhibition to novelty, Social orientation and Emotionality)

-

Verifying the existence of statistically significant differences temperament among temperament profiles (emotive, calm, normal, difficult) of preterm infants and preschool-aged full-term children.

Participants

The research group (Table 1), was made up by 105 children at the average age of 5 years and 2 months. Almost every child, whose characteristics were studied, had siblings (usually 2) and belonged to families of middle social class (average one-incoming families where parents had an average education level of secondary school). Children, were preschool aged, and they are enrolled in schools of Palermo and province.

The involved children were divided into two groups: an experimental group, so defined because of the presence of the variable "preterm birth", and a control group. The experimental group was made up by 50 preterm premature children, with low birth weight (mean gestational age = 29 weeks, ds = 2; mean birth weight = 1800 gr., ds = 350 gr.), selected in function of the following criteria: gestational age < 32 weeks, birthweight 1500 to 2500 gr. and lack of neurologic pathology, sensorial deficit and genetic pathology or malformative syndrome. The control group was made up by 55 full-term children (mean gestational age = 40 weeks with no pre- and perinatal complications), with the same anamnestic and sociocultural characteristics of the experimental group (cfr. Table 1). The selection criteria of the control group were: about 40th post conceptional week at birth (range = 39-41 gestational weeks), birthweight >2500 gr., lack of pre- and perinatal complications, and lack of neurologic pathology, sensorial deficit and genetic pathology or malformative syndrome.

Every child was involved in the research after getting a declaration of approval of their parents, who were informed about aims and procedures of research path to which the study is referred, they were requested to sign a data informative, under art.13 of D.LGS. 196/2003 granting people protection and other subjects in relation to personal data treatment.

Procedures and instruments

A questionnaire was used to observe the behaviour of children aged 3 to 6 years, belonging to the battery of Temperament Italian Questionnaires (QUIT), validated on Italian sample [21].

Such a questionnaire, which can be filled in by parents (even with a low, medium-low level of education), educators and teachers, or however, anyone who, taking care children, spends his/her time with them every day, was administered to infancy school teachers that child had been attended for 3 years.

The questionnaire is structured in 60 items describing child behaviour in three different contexts (child with the others; child on his play time; child facing of novelty or while s/he is performing an activity or a task), and the answers teachers can give are "almost never" [1] to "almost always" [6], under the Likert scale. The items refer to the six areas and dimensions previously described, each explored through 10 items (Motor Control Activity items n.11, 13, 15, 16, 34, 36-40, 45, 59; Attention items 41-44, 47, 54, 57, 58; Inhibition to novelty items 26, 29, 32, 35, 48-53, 56, 60; Social Orientation items 1-10; Positive Emotionality items 12, 17, 21, 23, 25, 27, 28, 31, 46 and Negative Emotionality items 14, 18-20, 22, 24, 30, 33).

More specifically, three areas are related to child's adjustment to environment in general: the Motor activity area, regarding the ability of performing motor activity, the Attention area regarding the ability of orienting and keeping the attention focus on a certain stimulus, and the Inhibition to novelty area related to the emotional reactivity to environmental stimuli.

The other three areas regard child's adjustment to social world and, in particular Social orientation area is meant in terms of attention and interest in social stimuli, Positive emotionality and Negative Emotionality areas refer to the prevalence of positive or negative emotions. The last two scales of QUIT (Positive emotionality and Negative emotionality) allow to clearly assess the emotional component of temperament ("quality of mood", 19), and highlight 4 temperament profiles, most consistent with Italian cultural context:

-

1.

Emotional temperament, typical of individuals with high emotional reactivity, who easily cry and laugh. They correspond to the definition of < < lively> >, nice and emotional child. Such a profile plan that the score obtained by the subject is higher than the mean value of the normative sample in the scale of both Positive emotionality (E+) and Negative emotionality (E-).

-

2.

Calm temperament, typical of individuals showing a low emotional reactivity. They smile instead of laughing and get angry, cry or get frightened rarely. These children get a score lower than the mean value of the normative sample in the scale of both Positive emotionality (E+) and Negative emotionality (E-).

-

3.

Normal temperament regarding those individuals showing a prevalence of positive emotions since the first months of their life. These children, having high positive reactivity and low negative reactivity, obtain a score higher than the mean value of the normative sample in the scale of Positive emotionality (E+) and a lower score in the scale of Negative emotionality (E-).

-

4.

Difficult temperament, describes those individuals where negative emotions prevail against positive ones. They are children whose interactions with environment are often difficult and the child-environment adjustment is extremely problematic. They obtain a score in the scale of Negative emotionality (E-) higher than the mean value of the normative sample, while a lower score in the scale of Positive emotionality (E+).

In relation to the psychometric characteristics of the questionnaire, there is the need to specify that it was validated on a great number of subjects (n = 1533) by means of a repeated administration to both parents and child's reference teachers, performed in several Italian cities.

More specifically, as for reliability and internal validity of the questionnaire, the internal consistence of the dimensions was calculated through Cronbach's alpha, which highlighted an acceptable cohesion among QUIT dimensions (α > .60 in every dimensions) [21]. Furthermore, correlational analysis was performed among the scales of the questionnaires filled in by fathers, mothers and teachers of children, by means of Pearson's correlation coefficient that highlighted the capacity of questionnaires to measure the objective aspects of temperament (R > .52 e p < .01) [21].

Data treatment and analysis

Data codified under the procedures set by the reference test guide, were analyzed by means of the statistical programme for Social Sciences - SPSS (16th version for Windows).

More specifically, in relation to the survey on likely differences between preterm and full-term children, within the different areas defining their temperament (QUIT), an analysis of one way variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables (scores related to different scales) was performed, and through Kolmogorov Smirnov's test [30], it allowed to compare the sample means of preterm infant group - experimental group/preterm birth independent variable - to those of children born after a normal gestation - control group/on time birth independent variable - within the different scales of QUIT. As for the test of significativity, a value of p = 0,05 was used.

Results and Discussion

The results of analysis on the differences between preterm and full-term children in the different areas of temperament, highlighted the existence of specific differences (Table 2).

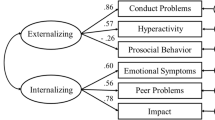

Statistically speaking, preterm infants seem to significantly differ from full-term children only in the scale related to Positive emotionality (p < .05) where they obtained a higher score than full-term children had, due to their higher predisposition toward expressing positive feelings and experiences. With regards to the other scales of QUIT (Social orientation, Inhibition to novelty, Motor control activity, Negative emotionality, Attention) preterm infants obtained lower scores compared to full-term children, even though such a difference does not have a statistic significance (p > .05) (see Table 2; Figure 1).

Moreover, as for the possibility to assess the different temperament profiles of preterm and full-term children, a descriptive comparison between mean scores and standard deviations of preterm and full-term children and the mean score and standard deviations of the normative test sample was performed in the Negative and Positive Emotionality scales (Table 3).

In relation to the specific temperament profile, preterm infants seem to be described with a normal temperament, showing high positive reactivity and low negative reactivity (mean score in E+ is higher than mean score in E-); on the other hand, full-term children, getting a low score in both E+ and E-, show less emotional reactivity and hence, highlight a calm temperament.

The results of such a study show how preschool-aged preterm infants, compared to full-term children are characterized by a temperament profile that, within Italian culture is defined in terms of "normality" and, hence, based upon a strong predisposition and orientation toward mainly expressing positive emotions. However, although a statistical significativity was not reached, preterm infants got slight lower scores in all other dimensions of temperament but in the positive emotional scale (see Table 2). So, preschool aged preterm infants involved in the research, seem to be also characterized by low levels of motor control activity, attention and negative emotive reactivity, by a predisposition toward motor and attention irregularity, and difficulty in recognizing and expressing negative emotions. Finally, preterm infants have a low score of social orientation meant as the relational curiosity functional to promote certain self-regulated answers of adjustment to external reality.

Conclusions

Such a study, though considering the small number of the sample, highlights a temperament profile of preschool-aged preterm infants whose specificity, compared to full-term children involved in the research path, is to be found in strong predisposition and orientation toward expressing positive emotions rather than negative ones, and a high trend toward searching the other and, hence, being sociable.

Moreover, it was detected the presence of a sort of "slowness" in preterm infants involved in the research, that, even though does not reach a statistical significativity, is mainly related to both motor and attention fields. So, it is to be highlighted a likely difficulty of motor control development in preschool-aged preterm infants, showing low levels of motor control activity, a less motor reactivity and difficulty of coordination and minor endurance of it [3]. The presence of such elements was detected by the literature in preterm infants compared to full-term children [17, 18].

Another aspect to be considered is related to preschool-aged preterm infants' attention. In accordance with several studies [22], a minor trend toward guiding and regulating their own attention, keeping focalization on an object, and a minor capability of moving their attention from a stimulus to another one, were highlighted. They all are processes whose impairment may be a likely risk factor for a rational adjustment to situations, and drive to difficulties in school learning.

In light of these last considerations, such a study is aimed to open new and future hypothesis on the existence of likely correlations between such temperament aspects and specific cognitive, emotive and relational functions of preterm infants. On the other side, it can guide paediatrician and neonatologist or, more generally, preterm infants cure system, in more focalizing and monitoring, within follow-up paths and related health status assessments, those cognitive, relational or motor control areas, correlated to temperament and that research data highlight in some way impaired. They are, in fact, extremely important processes for child's development [31–33], so that even the little impairment of them, seems to come with specific forms of evolutional maladjustments such as disorders and/or deficit of attention [3, 22], hyperactivity or disorders in emotive self-regulation [2], learning [34–37] and language disorders [38] that tend to guide the preterm infants' life path in terms of "atypical" path [39].

A further element that the study wants to highlight is related to cross-cultural perspective of data, that is, research preterm infants seem to be characterized by a temperament profile that, in its general configuration, can overlap to that highlighted by other studies performed on children coming from cultures deeply different from the considered one (United States, England, Australia, etc.) [33, 17, 2]. More specifically, while in Italian culture, the profile of temperament dimensions is defined in terms of "normality" and hence, adaptive to the reference socio-cultural context, in other cultures it is read using different parameters and models, and therefore, interpreted in terms of "difficult" functioning, that is not functional to adjustment to reality [40–43]. Such a consideration, even though it does not disregard the importance of cultural attributions that guide specific temperament profiles, leads to hypothesize and question about a likely presence of a sort of "temperament syndrome" [40] of preterm infants, meant as the existence of a configuration of temperament of preterm infants, made up by a strong constitutional base with a cross-cultural validity. Moreover, to support such hypothesis, it could be also considered that, while other studies have detected this temperament configuration of 0-to-2-year-old preterm infants, preterm children involved in such a research are all 5 years old. So, it has been supposed the permanence of such a syndrome during the development, that would lead to define preterm infants compared to full-term children, even school-aged, in terms of emotive, sociable and patient children yet less directive, attentive and reactive to frustrations.

Ethical approval

Not required. This is a retrospective study. Informed consent for developmental evaluation was given by parents of each child, under art.13 of D.LGS. 196/2003 granting people protection and other subjects in relation to personal data treatment.

The study was realized with the contribution of University of Studies of Palermo

References

Espy KA: Perinatal pH and Neuropsychological Outcomes at Age 3 Years in Children Born Preterm: An Exploratory Study. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2007, 32 (2): 669-682.

Clark CAC: Development of Emotional and Behavioral Regulation in Children Born Extremely Preterm and Very Preterm: Biological and Social Influences. Child Development. 2008, 79 (5): 1444-1462. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01198.x.

Hemgren E, Persson K: Associations of motor co-ordination and attention with motor-perceptual development in 3-year-old preterm and full-term children who needed neonatal intensive care. Child: care, health and development. 2006, 33 (1): 11-21. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00625.x.

Ornstein M, Ohlsson A, Edmonds J, Asztalos E: Neonatal follow-up of very low birthweight/extremely low birthweight infants to school age: A critical overview. Acta Paediatrica Scandinavica. 1991, 80: 741-748. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1991.tb11943.x.

Bonassi E, Gandione M, Rigardetto R, Di Cagno L: Il bambino prematuro che si affaccia alla vita: resoconto di tre esperienze di osservazione. Giornale di Neuropsichiatria dell'Età Evolutiva. 1989, 9 (3): 217-231.

Colombo G: I famigliari dei bambini ricoverati nei reparti di Terapia Neonatale: il ruolo e lo spazio assegnato, le loro aspettative. Neonatologia. 1996, 2: 53-60.

Theunissen NCM, Veen S, Fekkes M, Koopman HM, Zwinderman KAH, Brugman E, Wit J: Quality of life in preschool children born preterm. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2001, 43: 460-465. 10.1017/S0012162201000846.

Perricone G, Scimeca GP, Maugeri R: La nascita pretermine nell'ottica del "to care". Età evolutiva. 2004, 78: 85-92.

Peterson BS, Anderson AW, Ehrenkranz R, Staib LH, Tageldin M, Colson E, Gore JC, Duncan CC, Makuch R, Ment LR: Regional brain volumes and their later neurodevelopmental correlates in term and preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2003, 111 (5): 939-948. 10.1542/peds.111.5.939.

Als H, Gilkerson L, Duffy FH, Mcanulty GB, Buehler DM, Vendenberg K, Sweet N, Sell E, Parad RB, Ringer SA, Butler SC, Blickman JG, Jones KJ: A three-center, randomized, controlled trial of individualized developmental care for very low birth weight preterm infants: medical, neurodevelopmental, parenting, and caregiving effects. Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2003, 24: 399-408. 10.1097/00004703-200312000-00001.

Sansavini A, Guarini A, Ruffilli F, Alessandrini R, Giovanelli G, Salvioli GP: Fattori di rischio associati alla nascita pretermine e prime competenze linguistiche rilevate con il MacArthur. Psicologia Clinica dello Sviluppo. 2004, 1: 47-67.

Wright L: The pediatric psychologist: A role model. American Psychologist. 1967, 22: 323-325. 10.1037/h0037666.

Roberts MC, La Greca AM, Harper DC: Journal of Pediatric Psychology: Another stage of development. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1988, 13: 1-5. 10.1093/jpepsy/13.1.1.

Spirito A, Brown R, D'Angelo E, Delameter A, Rodrique J, Siegel L: Society of Pediatric Psychology Task Force Report: Recommendations for the training of pediatric psychologists. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2003, 28: 85-98. 10.1093/jpepsy/28.2.85.

Baldini L: Psicologia Pediatrica. 2009, Italia, Piccin Nuova Libraria SPA

Nigg JT, Goldsmith HH, Sachek J: Temperament and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: The Development of a Multiple Pathway Model. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004, 33 (1): 42-53. 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_5.

Sajaniemi N, Salokorpi T, von Wendt L: Temperament profiles and their role in neurodevelopmental assessed preterm children at two years of age. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998, 7 (3): 145-152. 10.1007/s007870050060.

Oberklaid F, Sewell J, Sanson A, Prior M: Temperament and behavior of preterm infant: a six-years follow-up. Pediatrics. 1991, 87 (6): 854-861.

Thomas A, Chess S: Temperament and Personality. Temperament in Childhood. Edited by: Kohnstam GA, Bates JA, Rothbart MK. 1989, New York, John Wiley and Sons Ltd, 249-262.

Attili G, Felaco R, Alcini P: Temperamento e relazioni interpersonali. Età Evolutiva. 1989, 32: 39-49.

Axia G: Questionari Italiani per il Temperamento. 2002, Trento, Erickson

Gillberg C: Deficits in attention, motor control, and perception: a brief review. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2003, 88: 904-910. 10.1136/adc.88.10.904.

Hughes MB, Shults J, McGrath J, Medoff-Cooper B: Temperament characteristics of premature infants in the first year of life. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2002, 23: 430-435.

Watt J: Interaction and development in the Þrst year. The effects of prematurity. Early Human Development. 1986, 13: 195-210. 10.1016/0378-3782(86)90008-3.

Gennaro S, Tulman L, Fawcett J: Temperament in preterm and full-term infants at three and six months of age. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1990, 36: 201-215.

Simons CJ, Ritchie SK, Mullett MD: Relationships between parental ratings of infant temperament, risk status, and delivery method. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 1992, 6: 240-245. 10.1016/0891-5245(92)90021-U.

Medoff-Cooper B: Temperament in very low birth weight infants. Nursing Research. 1986, 35: 139-142. 10.1097/00006199-198605000-00004.

Washington J, Minde M, Goldberg S: Temperament in preterm infants: Style and stability. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 1986, 26: 493-502. 10.1016/S0002-7138(10)60008-8.

Oberklaid F, Prior M, Sanson A: Temperament of preterm versus fullterm infants. Developmental and Behavioral. Pediatrics. 1986, 7: 159-162.

Ercolani AP, Areni A, Leone L: Statistica per la psicologia II. Statistica inferenziale e analisi dei dati. 2007, Bologna, Il Mulino

Rothbart MK, Posner M, Hershey KL: Temperament, attention, and developmental psychopathology. Developmental psychopathology. Edited by: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ. 1995, New York, Wiley, II: 315-340.

Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Evans DE: Temperament and personality: Origins and outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000, 78: 122-135. 10.1037/0022-3514.78.1.122.

Sajaniemi N: Cognitive Development, Temperament and Behavior at 2 Years as Indicative of Language Development at 4 Years in Pre-Term Infants. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2001, 31 (4): 329-349. 10.1023/A:1010238523628.

Saigal S, Hoult L, Streinder D: School difficulties in adolescences in a regional cohort of children who were extremely low birthweight. Pediatrics. 2000, 105: 325-331. 10.1542/peds.105.2.325.

Taylor HG, Alden J: Age-related differences in outcomes following childhood brain insults: An introduction and overview. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 1997, 3: 555-567.

Espy KA, McDiarmid MD, Cwik MF, Senn TE, Hamby A, Stalets MM: The contributions of executive functions to emergent mathematic skills in preschool children. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2004, 26: 465-486. 10.1207/s15326942dn2601_6.

Taylor HG, Klein NK, Minich NM, Hack M: Middle-school-age outcomes in children with very low birthweight. Child Development. 2000, 71: 1495-1511. 10.1111/1467-8624.00242.

Hopkins-Golightly T, Raz S, Sander C: Influence of slight to moderate risk for birth hypoxia on acquisition of cognitive and language function in the preterm infant: A cross-sectional comparison with preterm-birth controls. Neuropsychology. 2003, 17: 3-13. 10.1037/0894-4105.17.1.3.

Ghirri Paolo: Prevalence of hypospadias in Italy according to severity, gestational age and birthweight: an epidemiological study. Italian Journal of Pediatrics. 2009, 35: 1-18. 10.1186/1824-7288-35-18.

Attili G, Vermigli P, Travaglia G: Variabilità culturale e temperamento: il bambino difficile. Età evolutiva. 1991, 40: 18-31.

Axia G: La misurazione del temperamento nei primi tre anni di vita. 1993, Padova, Cleup

Minde K: The social and emotional development of low-birthweights infants and their families up to age 4. The psychological development of low birthweight children. Edited by: Friedman SL, Sigman MD. 1992, Norwood, Ablex, 157-187.

Axia G, Moscardino U: La valutazione del temperamento. La valutazione del bambino. Edited by: Axia G, Bonichini S. Roma, Carocci. 2000, 109-137.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the school staff of the childhood's schools of I.C. "Campofelice di Roccella - Lascari" (PA) and of I.C. "M. Buonarroti" (PA) Italy.

Special thanks to Dr. F.R. Nuccio for the support the administration of the instruments.Special thanks to Dr. G. Anzalone for the collaboration at the english language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The author declares that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

The authors contributed equally to this work. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Giovanna Perricone and M Regina Morales contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Perricone, G., Morales, M.R. The temperament of preterm infant in preschool age. Ital J Pediatr 37, 4 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1824-7288-37-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1824-7288-37-4