Abstract

Background

Coral reefs are among the most diversified ecosystems in the world, but suffer from anthropogenic and natural disturbances, often causing a shift from coral to algal (or other benthic groups) dominated ecosystems. Linking benthic communities’ information with water quality data is urgently needed to understand current and future changes in benthic dominance. This research examined possible environmental causes on the abundance of the zoanthid Palythoa tuberculosa on Okinawa Island in southern Japan. Various water parameters (temperature, dissolved oxygen, salinity, pH, particulate organic matter, chlorophyll a, NO2-N, NO3-N, PO4-P, NH4-N, and the distance to the river mouth) were recorded along with benthic community composition at eight locations.

Results

Turf algae, coralline algae, or sand, rubble and rock dominated most locations in this survey. Coral coverage was moderate (10% to 40%). P. tuberculosa was generally low in abundance, but common at Mizugama (9% of the benthic community) and Oku (25%). Water parameters varied among sites. Salinity was the only parameter correlated with the abundance of Palythoa (R 2 a = 0.47). P. tuberculosa had a positive relationship with the presence of coralline algae, Pocillopora, Goniastrea, and Porites, and had negative correlation with turf algae and other invertebrates.

Conclusions

Likely no single parameter is related to the coverage of P. tuberculosa on Okinawa Island. Nutrients were found at low concentrations at the sites, and may explain why there was no strong relationship observed between P. tuberculosa and nutrients. Based on these first results, further long-term monitoring combined with the collection of additional environmental data and benthic surveys are needed to better explain the abundance of P. tuberculosa. Such data would be particularly helpful to understand how reef organisms will interact with their environment under scenarios of future climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Coral reef ecosystems are often called the 'tropical rain forests of the sea’ and have the highest biodiversity among ocean ecosystems (Knowlton and Jackson2008; Bellwood et al.2004; Hoegh-Guldberg et al.2007). However, coral reefs are facing severe degradation due to anthropogenic activities and climatic changes. Over-fishing (Hughes et al.2007), water pollution, extra nutrient input (Szmant2002), and sedimentation from terrestrial runoff (De'ath and Fabricius2010) are the main disturbances causing shifts in the dominance of benthic taxa. Over 50% of the world coral reefs are already considered as heavily degraded, and a further 25% will become degraded in the next decade (Wilkinson2008).

The degradation of water quality plays an important role in the shift from coral to algal (or other alternative taxa) dominated reefs (Bellwood et al.2004; Knowlton and Jackson2008). However, its effects on the occurrence of some benthic taxa are still poorly understood. While over-fishing has been considered the main factor causing algal over-growth (Done1992; Hughes et al.2007), extra nutrient input (Szmant2002) is also considered as important. The Great Barrier Reef has shown a long-term decline in coral cover in favor of algae correlated to a decline in water quality (De'ath and Fabricius2010). Similarly, nutrient overload has also been reported to affect negatively coral reef communities from Okinawa (West and van Woesik2001), Taiwan (Meng et al.2008), Hong Kong (Morton1994), Reunion Island (Naim1993), and the Red Sea (Loya2004), where algae have become dominant at some locations. Sponges are also known to overgrow corals and dominate in locations in the Florida Keys, Belize and Puerto Rico, and in the Pacific Ocean (Rutzler and Muzik1993; Kelly et al.2003; Liao et al.2007; Fujii et al.2011; Reimer et al.2011a,b) due to water pollution from human sewage (Ward-Paige et al.2005), coral disease, and bleaching (Aronson et al.2002; Weil et al.2002). Water pollution may be a key factor of corallimorpharian (Anthozoa: Hexacorallia: Corallimorpharia) outbreak in the Red Sea (Chadwick-Furman and Spiegel2000; Loya2004; Work et al.2008). One species of sea anemone (Anthozoa: Hexacorallia: Actiniaria) has been observed replacing the dominant Acropora coral community in southern Taiwan, and this was possibly related to chronic terrestrial runoff and tourism pressure combined with the catastrophes of a large typhoon and mass coral bleaching events (Chen and Dai2004). The factors involved in phase shifts on coral reefs appear to be diverse, but declining water quality is likely to be one of the major driving factors behind these shifts (Chen and Dai2004). Overall, there is a lack of long-term monitoring of coral reef benthic communities together with water quality and also of precise descriptions of changes in benthic communities correlated with water quality parameters.

Zoanthids (Anthozoa: Hexacorallia: Zoantharia) are common shallow reef benthic organisms, and some zooxanthellate genera such as Palythoa and Zoanthus are aggressive benthic competitors (Suchanek and Green1981; Sebens1982) in specific environmental conditions. In the Pacific, the species Palythoa tuberculosa is common in shallow reef areas and is abundant on reef flats and crests in Okinawa (Irei et al.2011) and in other locations such as in Taiwan (CF Dai and CY Kuo, personal communication). The encrusting form of P. tuberculosa combined with up to 65% sand content (Haywick and Mueller1997) makes it resistant to strong wave energy (Suchanek and Green1981; Irei et al.2011). P. tuberculosa is an active planktonivore (Fabricius and Metzner2004), also hosts a generalist Symbiodinium type (Reimer et al.2006; Hibino et al.2013), and during bleaching events can survive via heterotrophy (Reimer1971a,b), which allows them to have low mortality during bleaching events (Jimenez2001), unlike many other bleaching-susceptible anthozoans. Due to a lack of data on the abundance of P. tuberculosa, whether this species is naturally abundant or has recently increased in coverage due to induced over-growth by changing environmental conditions is unknown. Studies from Brazil (Costa et al.2008) demonstrated a positive relationship between Palythoa abundance and nutrient-enriched coastal areas. However, no such studies have been conducted in the Pacific.

Okinawa Island is in the Ryukyu Archipelago in southern Japan and is known for its highly diverse coral reefs. However, it has been under increasing anthropogenic threat from coral bleaching (Yamazato1999; Loya et al.2001; van Woesik et al.2004), coastal development, and declining water quality (Roberts et al.2002; Ramos et al.2004). At some potentially degraded coral reef locations on Okinawa Island near river mouths, the shallow water communities (1 to 6 m depth) have high coverage of P. tuberculosa (Figure 1). This provides an opportunity to examine how the abundance of P. tuberculosa is related to environmental parameters in these shallow coral reef waters. To examine this question, water quality parameters and benthic communities were surveyed at eight locations around Okinawa Island.

Methods

Experimental design

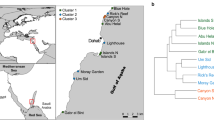

The study was carried out along the west and north coasts of Okinawa Island, in the Ryukyu Islands, Japan (Figure 2 and coordinates in Table 1). Okinawa Island is located in the subtropical region, and influenced by the warm Kuroshio Current that contributes to high marine biodiversity (Roberts et al.2002). Annual water temperatures average from 21°C to 28°C throughout the year (Japan Meteorological Agency2013). Eight locations from north to south were sampled: Oku, Bise, Manza, Mizugama, Toguchi, Sunabe, Convention Center, and Makiminato. More data about each location's proximity to rivers as well as on nearby coastal land use/conditions are found in Table 1.

Benthic community surveys

This survey primarily focused on the reef crest and reef flat, which are considered as the preferred habitats for P. tuberculosa (Irei et al.2011). Benthic communities were surveyed at each location between July and August 2011 for Bise, Manza, Mizugama, Convention Center, and Makiminato, and May to June 2012 for Oku, Toguchi, and Sunabe. At each location, six 5-m random transect lines were recorded, and serial photos were taken (Canon IXY 920IS; Canon Inc., Tokyo, Japan) along each side of the transect using a 0.5 × 0.5 m quadrat. This study utilized a relatively short (5 m) transect line to avoid topography gaps (e.g., deep spurs and grooves, and channels). The benthic community coverage rates were calculated from 120 random points of each photo using Coral Point Count with Excel extensions program (CPCe) (Kohler and Gill2006). The main benthic groups in this study were turf algae, macroalgae, corals, P. tuberculosa, soft corals, coralline algae, other invertebrates, and sand, rubble, and rock (SRR). Combined with detailed information on coral categories, there were 24 groups in total. Anthozoans were identified to family level, except for P. tuberculosa. Some corals, beside Fungiidae, Merulinidae, Agariciidae, and Lobophylliidae, were identified to their genus level, namely, Acropora, Galaxea, Goniastrea, Montipora, Pocillopora, Porites, Psammocora, Euphyllia, Goniopora, Plesiastrea, Millepora, and Astreopora following Fukami et al. (2008) and Budd et al. (2012). When individual corals were unable to be identified (e.g., too small), they were designated as 'unknown corals’.

Water sampling and analyses

Water was sampled from Oku, Bise, Manza, Mizugama, Toguchi, Sunabe, Convention Center, and Makiminato at high tide on non-rainy days between the middle of May and the middle of July in 2012. Water temperature was measured using HOBO underwater temperature loggers (UA-002-64, Onset, MA, USA) at five locations (Makiminato, Convention Center, Mizugama, Manza, and Bise) from May 2012 to June 2012, while temperature at the other locations was measured at the time of the sampling using a multi-parameter water quality meter (model WQC-24, DKK-TOA, Tokyo, Japan). Using the same multi-parameter meter, dissolved oxygen (DO), salinity, and pH were measured in parallel. Around 10 L of seawater were sampled at each location, kept in a cooler, and filtered within 1 h through Whatman glass microfiber GF/F filters (pore size = 0.7 μm; Whatman International Ltd., Maidstone, UK). One liter of seawater was filtered for nutrient contents and particulate organic matter (POM); 2 L for chlorophyll a (Chl a) and 100 ml of the filtered seawater were preserved for nutrient assessment (NO2-N, NO3-N, PO4-P, and NH4-N). All seawater samples were then preserved at -20°C in the dark until analyses. Chl a was extracted using acetone and measured using spectrophotometer following the protocol described by Aminot and Rey (2000). The nutrient levels (NO2-N, NO3-N, PO4-P, and NH4-N) were quantified using a continuous flow analyzer QuAAtro2-HR (BL-TEC, Osaka, Japan) by following manufacturer's instructions. The Whatman GF/F filters for POM were dried in 80°C and burned at 500°C for 4 h, and the weight was measured before and after burning to calculate POM yield.

Data analyses

In order to satisfy underlying assumptions of statistical analyses and avoid type I and type II errors, the data sets were subjected to transformations prior to multivariate analyses.

The water variables were log-transformed to stabilize their variance, reduce the effects of outliers, and to linearize relationships between variables. Structure and relationships between the environmental parameters (POM, Chl a, NO2-N, NO3-N, PO4-P, NH4-N, salinity, temperature, and DO) among locations were analyzed by performing principal component analysis (PCA) on the transformed data set and by Pearson correlations. To determine if the variation of the environmental parameters are linked to the terrestrial water runoff into the sea, the distance to the closest river mouth were included in the analyses. The statistics of Pearson (r) were tested under 5,000 permutations (Legendre2005).

The benthic coverage data were subjected to the Hellinger transformation. This method consists of dividing the abundance values by the total abundance in the locations, and then taking the square root of this result. This transformation is recommended for linear ordinations as it reduces the importance of the most common groups and preserves distances between locations in case of absences of some groups at different locations (Rao1995; Legendre and Gallagher2001; Legendre and Legendre2012). To reinforce this last point and avoid disproportionate effects of rare groups in the model, the benthic groups with maximum coverage of less than 5% were removed from analyses. After this, only Merulinidae, Acropora, Galaxea, Goniastrea, Montipora, Pocillopora, Porites, and Psammocora, turf algae, macroalgae, P. tuberculosa, soft corals, coralline algae, unknown corals, other invertebrates, and SRR remained.

The gradient of benthic composition along the coasts and associations between the benthic groups were analyzed by PCA. For a better view of associations among locations, PCA results were coupled with a clustering analysis following the least-square method of Ward, a hierarchical clustering which can be related to linear methods, such as PCA, in the present case. The number of clusters was determined by Mantel statistics, by calculating the correlation between the original distance matrix and each binary matrix issued from the different levels of the dendrogram. The optimal number of clusters chosen for the final clustering corresponded to the binary matrices presenting the highest correlation with the original distance matrix (Legendre and Legendre2012). The relationship between P. tuberculosa and the benthic groups was also tested by Pearson correlations under 5,000 permutations (Legendre2005).

To determine which of the environmental parameters interacted with P. tuberculosa distribution, a regression analysis was performed on P. tuberculosa data with the environmental variables and with the subset of distance to the water networks. Multiple regression was tested by 5,000 permutations. The coefficient of determination R 2 (R 2 a) was adjusted by the Ezekiel formula (Ezekiel1930). Prior to constrained ordination and regression analyses, covariates exhibiting a high level of colinearity were removed as such variables can cause instability in the model and misinterpretation of the estimators (Zuur et al.2010). In each model, the colinearity was estimated by compiling the variance inflation factor (VIF) of each variable: the variable exhibiting the highest VIF was dropped, and the VIFs of the remaining variables were compiled again. We repeated the process until all VIFS were under the cutoff threshold of 10 as proposed by Neter et al. (1996).

All statistical analyses were compiled with R software.

Results

Environmental parameters

Detailed information of all water parameters are shown in Table 2. The water temperatures from the 2 months of measurement from five locations showed there were less than 0.5°C differences among all five locations, despite depths being slightly different (Table 2). Salinity, pH, and DO at all locations fluctuated within the natural expected reef environmental ranges (salinity between 25‰ to 42‰ (Coles and Jokiel1992); pH usually between 8.0 to 8.2, but fluctuating from 7.5 to 8.4 (Meng et al.2008); DO between 2.1 to 10.8 mg L-1 (Kinsey and Kinsey1967)) despite some locations being close to river mouths. Nutrient concentrations (NO2-N, NO3-N, NH4-N, PO4-P, and Chl a) were all within the level of concentration expected at a general reef area with low nutrient input. The results of the PCA (Figure 3) illustrate the relationships between the variables. The proportions of variation explained by the first two axes were 43.38% and 26.37%, respectively. The first axis displayed a strong gradient of the environmental conditions among the locations: Bise, Manza, Oku, and Sunabe, which are far from river mouths, were grouped on one side of the PCA with high POM, PO4-P, and pH; while Makiminato, Mizugama, Toguchi, and Convention Center, which are closer to river mouths and had higher NO3-N, NO2-N and NH4-N inputs, were on the other side of the PCA. The second axis separated locations with high temperature (Manza, Makiminato, and Convention Center) and high Chl a contents (Toguchi and Sunabe). The Pearson correlation test showed strong correlations between the nutrients and organic matter contents and the distance to the river mouths: the PO4-P and POM contents increased significantly with the distance to the river mouths (r = 0.43, p < 0.01 and r = 0.58, p < 0.001, respectively), while the NO3-N, NO2-N and NH4-N decreased when moving away from the river mouths (r = -0.86, p < 0.001, r = -0.84, p value < 0.001, and r = -0.76, p < 0.001, respectively). The pH and DO were also positively correlated to the distance to river mouths (r = 0.67, p = 0.001 and r = 0.47, p < 0.001, respectively). Neither temperature nor salinity was significantly correlated with the distance to river mouths.

Benthic composition

Benthic composition at most of the locations had high turf or coralline algae coverage ranging between 40% and 70% (Figure 4). For benthic organisms, Mizugama was the only location mainly dominated by hard corals (~40%). Convention Center and Toguchi had moderate soft coral coverage (25% and 15%, respectively), but low hard coral coverage. Other locations had moderate hard coral coverage ranging from 10% to 40%. P. tuberculosa coverage was low in Makiminato (<1%), Convention Center (<1%), Sunabe (2%), Toguchi (1%), Manza (1%), and Bise (1 %), but higher in Mizugama and Oku (9% and 25%, respectively). The detailed coral group compositions of locations are shown in Figure 5. Although Makiminato, Sunabe, and Manza had similar amounts of hard coral coverage, their hard coral composition was different. Mizugama was dominated by Montipora, whereas Bise and Oku were dominated by Acropora. The results of the PCA of the benthic association coupled with cluster analysis are shown in Figure 6. The benthic community was clustered into six large groups, distributed along a north–south gradient along the coast of Okinawa Island (Figure 6). The northern part showed dominance of coralline algae and P. tuberculosa. Moving south, locations were gradually dominated by turf algae and coralline algae mixed with some hard coral groups, and finally in SRR, turf algae and some soft coral or macroalgae in the most southern locations. Pearson correlation showed that P. tuberculosa had a positive relationship with coralline algae (r = 0.47, p < 0.01), Pocillopora (r = 0.65, p < 0.001), Goniastrea (r = 0.47, p < 0.01), and Porites, (r = 0.3, p < 0.05), and had negative correlation with turf algae (r = -0.58, p < 0.001) and other invertebrates (r = -0.28, p = 0.05), with no significant correlation with other groups.

Principal component analysis of benthic community data with cluster group on the map. The legend represents the dominant benthic groups in that cluster (TURF, turf algae; MACR, macroalgae; Coralline, coralline algae; Invertebrates, other invertebrates; SOFT, soft corals; SRR, sand, rubble, and rock; MK, Makiminato; CC, Convention Center; SB, Sunabe; MG, Mizugama; TG, Toguchi; MZ, Manza; BS, Bise; OK, Oku. PC1 = 28.24%; PC2 = 12.74%).

Analysis of the determinants of the P. tuberculosa abundance

The VIFs of the variables NO3-N, NO2-N, and DO were superior to the cutoff threshold of 10 and did not show any correlation with the benthic groups. By consequence, these variables were removed prior to the analysis. Multiple regression with the environmental variables on P. tuberculosa data showed that salinity was the only sampled variable which contributed significantly to the coefficient of multiple regression (R 2 a = 0.4727, p <0.001).

Discussion

In the current study, P. tuberculosa abundance was found to have a positive correlation with coralline algae and three hard coral groups, Pocillopora, Goniastrea, and Porites, but had a negative correlation with turf algae and 'other invertebrates’. For anthozoans, coralline algae can be construed as 'open’ benthic space as they often settle on top of coralline algae (Heyward and Negri1999), whereas turf algae compete with other benthic organisms for space. Similar results were also reported in Costa et al. (2008), which implies Palythoa may prefer more open reef areas such as outer reef crests (Irei et al.2011). In this study, other invertebrates consisted mainly of grazing sea urchins and a few sea cucumbers, and these taxa can be expected to have a direct correlation with the abundance of turf algae. The three hard coral groups that had positive correlations with P. tuberculosa are commonly found in shallow reefs, and it is therefore difficult to speculate of the nature of the association between P. tuberculosa and these groups.

The multiple regression analyses indicated salinity was significantly correlated with the coverage of P. tuberculosa, however, the range of the salinity did not fluctuate much among locations. Salinity ranged from 29.8 to 32.2 ‰, levels that are within normal seawater ranges (Coles and Jokiel1992). Despite some locations in this study being located close to river mouths, salinity did not reach the low levels as seen in Meng et al. (2008), where locations next to stream outlets dropped to 5-15‰. The non-significant correlation observed in this study between the abundance of P. tuberculosa and nutrient input may be due to nutrient levels being low compared to Costa et al. (2008). Furthermore, the sampling timing of this study may have influenced the results of water parameters as all the water was sampled during high tide, when runoff of nutrients into the sea maybe more difficult to observe than during low tide. This could explain why the range for salinity was small and no strong relationships were observed between other environmental parameters and P. tuberculosa distribution in this study. Previously, Palythoa in Brazil was found to be abundant at locations with extra nutrient input (Costa et al.2008); however, nutrient levels detected by Costa et al. (2008) were much higher than the levels observed in this study. In their survey the total oxidized nitrogen (TON = NO3 - + NO2 -) and soluble reactive phosphorus (SRP) from high-nutrient input sites were approximately 2.0 to 2.5 μM and 0.7 to 0.75 μM, respectively. In the current survey, TON ranged from approximately 0.2 to 1.4 μM (except for 4.2 μM in Toguchi), and phosphate (PO4-P) levels were all lower than 0.18 μM. Chl a concentrations were also higher in Costa et al. (2008) (0.8 to 1.3 μg/L) than in our research (0.01 to 0.5 μg/L). Furthermore, Costa et al. (2008) examined reactive silica (DSi), which was not examined in current study, and this may also play an important role in explaining the high coverage of Palythoa. However, Costa et al. (2008) only surveyed nutrient-related parameters and did not examine other physical parameters examined in the current study, such as temperature, pH, DO, and salinity. In this study, salinity was the only factor in multiple regression that significantly correlated with P. tuberculosa, but other parameters not investigated here (e.g., in Costa et al.2008) may also be important.

Although the range of salinity in this survey was small, the significant correlation between salinity and P. tuberculosa should not be ignored. Low salinity is caused by river, ground water, or precipitation input, which often include nutrients from land (Bell1992; Costa et al.2008; Meng et al.2008). Although there were no significant correlations between salinity and the distance to river mouths in this study, NO3-N, NO2-N, and NH4-N had all strong negative correlations with distance to river mouths and were higher in locations close to rivers (Makiminato, Mizugama, Toguchi, and Oku). Despite nutrient input being related to the distance from rivers, some important differences between locations were observed. For example, Toguchi had higher nitrogen levels than Mizugama, although they were the same distance from the closest river. This may be due to the location of the river mouth; the sampling location at Mizugama is located on the southern edge of the river mouth and received less impact than the site at Toguchi, which is located at the northern edge of the same mouth. Sites at Convention Center and Sunabe are not located near rivers yet still exhibited some degree of nutrient input, which may imply terrestrial runoff (Table 2 and Figure 3; also Szmant2002; Fabricius2005), as both sites are located adjacent to dense mixed residential/commercial/industrial areas. Around Okinawa Island there are other locations near rivers that experience terrestrial runoff and have been found to have high coverage of P. tuberculosa (Irei et al.2011), particularly two locations in southern Okinawa Island; Minatogawa (216 colonies per 30 m2) and Odo (155 colonies per 30 m2). As well, on the east coast of Okinawa Island, the location of Teniya (SYY and JDR, personal observation; Figure 2) was observed to have high P. tuberculosa coverage. Minatogawa and Teniya are close to river mouths (Table 2), and Odo has large amounts of freshwater runoff from small creeks (Sakai and Nishihira1991; Hibino et al.2013). Rivers and terrestrial runoff both appear to cause extra nutrient input on Okinawa Island reefs; however, input fluctuates throughout the year (Meng et al.2008). Despite the small range of salinity variation and low correlation levels with other nutrients (perhaps due to the sampling timing), long-term monitoring during low tides should be conducted to further evaluate the role that salinity and nutrient input may play in explaining P. tuberculosa abundance.

In Brazil, high coverage of Palythoa was observed to be approximately 30% (Costa et al.2008), while at Oku, in this study, P. tuberculosa coverage was approximately 25% despite lower nutrient levels than in the study of Costa et al. (2008). Beside high nutrient concentration and low salinity, other potential factors such as benthic competition or other physical features might also influence the abundance of Palythoa. Among the other physical factors, wave energy could be considered as an important factor. P. tuberculosa are active planktonivores (Fabricius and Metzner2004), and their polyp shape which is optimized for feeding under strong water flow (Koehl1977) makes Palythoa a specialist of semi-disturbed reef crests and reef slopes (Suchanek and Green1981; Irei et al.2011). Hence, quantifying the wave energy should also be considered in the future research.

Much research has focused on the influence of environmental parameters on hard corals and macroalgae, and there are only a few studies investigating other benthic groups (e.g., West and van Woesik2001; Costa et al.2008). Despite the different physiological responses that increased nutrient levels can have on benthic reef organisms, increased nutrient input generally causes coral reef diversity to decrease (Fabricius2005). Although there were no signs of macroalgal over-growth in this survey, some locations were sub-dominated by soft corals and had low hard coral coverage (Figure 4). Locations to the south of Toguchi had between 5% and 26% soft coral coverage. In other studies soft corals have been observed to increase in abundance with increased nutrient input (McClanahan et al.2002). West and van Woesik (2001) surveyed how river discharge and human population affected benthic composition in Okinawa, and their survey at Toguchi found that hard coral cover was approximately 11%, soft coral 1%, and Palythoa was only 0.1%; while in the current research, Palythoa was 0.5%, hard coral cover was only 1.5%, but soft coral had risen to 15%. Therefore, it could be possible that locations such as Makiminato, Sunabe, and Mizugama that do not have high soft coral coverage but suffer from high nutrient input may, in the future, gradually become dominated by soft corals under multiple disturbances. Nevertheless, many soft corals are susceptible to bleaching (Loya et al.2001; van Woesik et al.2011), and considering the prediction of continued climate change in the future (Hoegh-Guldberg1999), soft coral dominance may only be a short-term phenomenon. Such a situation may be the same for P. tuberculosa, and instead of becoming dominant under climate change and anthropogenic disturbances, this species may become more abundant in transition stage(s) during phase shifts, particularly with higher fresh water or nutrient input.

Conclusions

It is still difficult to conclude why P. tuberculosa is particularly abundant in some locations on Okinawa Island; however, the high correlation with salinity implies extra fresh water input on reefs may be a key factor. Future coral reefs will continue to suffer from high nutrient input, and accompanied by other disturbances such as typhoons or bleaching, reefs may shift to soft coral dominance. Furthermore, if preferable conditions occur, for instance under increased anthropogenic stress, these reefs may shift to aggressive and rapidly growing benthic zoanthids such as P. tuberculosa. It is still unknown what the ecological consequences of a phase shift to P. tuberculosa dominance would be. Currently, data on reef benthic groups and water quality are lacking in many areas of the Indo-Pacific region. An examination of reefs within predetermined regions combined with more complete environmental data will aid in understanding the dynamics of reef benthic organisms during climate change and anthropogenic disturbances.

Abbreviations

- Chl a:

-

Chlorophyll a

- DO:

-

Dissolved oxygen

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- POM:

-

Particulate organic matter.

References

Aminot A, Rey F: Standard procedure for the determination of chlorophyll a by spectroscopic methods. Copenhagen, Denmark: International Council for the Exploration of the Sea; 2000. ISSN 0903–260. Techniques in Marine Environmental Sciences, Nr. 28

Aronson RB, Precht WF, Toscano MA, Koltes KH: The 1998 bleaching event and its aftermath on a coral reef in Belize. Mar Biol 2002, 141: 435–447. 10.1007/s00227-002-0842-5

Bell PRF: Eutrophication and coral reefs: some examples in the Great Barrier Reef lagoon. Water Res 1992, 26: 553–568. 10.1016/0043-1354(92)90228-V

Bellwood DR, Hughes TP, Folke C, Nyström M: Confronting the coral reef crisis. Nature 2004,429(6994):827–833. 10.1038/nature02691

Budd AF, Fukami H, Smith ND, Knowlton N: Taxonomic classification of the reef coral family Mussidae (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Scleractinia). Zool J Linn Soc 2012, 166: 465–529. 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2012.00855.x

Chadwick‒Furman NE, Spiegel M: Abundance and clonal replication in the tropical corallimorpharian Rhodactis rhodostoma . Invertebrate Biology 2000, 119: 351–360.

Chen CA, Dai CF: Local phase shift from Acropora -dominant to Condylactis -dominant community in the Tiao-Shi Reef, Kenting National Park, southern Taiwan. Coral Reefs 2004, 23: 508–508.

Coles SL, Jokiel PL: Effects of salinity on coral reefs. In Pollution in tropical aquatic systems. Edited by: Connell DW, Hawker DW. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1992:147–166.

Costa OS Jr, Nimmo M, Attrill MJ: Coastal nutrification in Brazil: a review of the role of nutrient excess on coral reef demise. J South Am Earth Sci 2008, 25: 257–270. 10.1016/j.jsames.2007.10.002

De'ath G, Fabricius K: Water quality as a regional driver of coral biodiversity and macroalgae on the Great Barrier Reef. Ecol Appl 2010, 20: 840–850. 10.1890/08-2023.1

Done TJ: Phase shifts in coral reef communities and their ecological significance. Hydrobiologia 1992, 247: 121–132. 10.1007/BF00008211

Ezekiel M: Methods of correlation analysis. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1930.

Fabricius KE: Effects of terrestrial runoff on the ecology of corals and coral reefs: review and synthesis. Mar Pollut Bull 2005, 50: 125–146. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2004.11.028

Fabricius KE, Metzner J: Scleractinian walls of mouths: predation on coral larvae by corals. Coral Reefs 2004, 23: 245–248.

Fujii T, Keshavmurthy S, Zhou W, Hirose E, Chen CA, Reimer JD: Coral-killing cyanobacteriosponge Terpios hoshinota on the Great Barrier Reef. Coral Reefs 2011, 30: 483–483. 10.1007/s00338-011-0734-6

Fukami H, Chen CA, Budd AF, Collins A, Wallace C, Chuang Y-Y, Chen C, Dai C-F, Iwao K, Sheppard C, Knowlton N: Mitochondrial and nuclear genes suggest that stony corals are monophyletic but most families of stony corals are not (Order Scleractinia, Class Anthozoa, Phylum Cnidaria). PLoS One 2008,3(e3222):1–9.

Haywick DW, Mueller EM: Sediment retention in encrusting Palythoa spp. - a biological twist to a geological process. Coral Reefs 1997, 16: 39–46. 10.1007/s003380050057

Heyward AJ, Negri AP: Natural inducers for coral larval metamorphosis. Coral Reefs 1999, 18: 273–279. 10.1007/s003380050193

Hibino Y, Todd P, Ashworth CD, Obuchi M, Reimer JD: Monitoring colony colour and zooxanthellae ( Symbiodinium spp.) condition in the reef zoanthid Palythoa tuberculosa in Okinawa, Japan. Mar Biol Res 2013, 9: 794–801. 10.1080/17451000.2013.766344

Hoegh-Guldberg O: Climate change, coral bleaching and the future of the world's coral reefs. Mar Freshw Res 1999, 50: 839–866. 10.1071/MF99078

Hoegh-Guldberg O, Mumby PJ, Hooten AJ, Steneck RS, Greenfield P, Gomez E, Hatziolos ME: Coral reefs under rapid climate change and ocean acidification. Science 2007,318(5857):1737–1742. 10.1126/science.1152509

Hughes TP, Rodrigues MJ, Bellwood DR, Ceccarelli D, Hoegh-Guldberg O, McCook L, Moltschaniwskyj N, Pratchett MS, Steneck RS, Willis B: Phase shifts, herbivory, and the resilience of coral reefs to climate change. Curr Biol 2007, 17: 360–365. 10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.049

Irei Y, Nozawa Y, Reimer JD: Distribution patterns of five zoanthid species in Okinawa Island, Japan. Zool Stud 2011, 50: 426–433.

Japan Meteorological Agency 2013.

Jime´nez C: Bleaching and mortality of reef organisms during a warming event in 1995 on the Caribbean coast of Costa Rica. Revista De Biología Tropical 2001, 49: 233–238.

Kelly M, Hooper J, Paul V, Paulay G, van Soest R, de Weerdt W: Taxonomic inventory of the sponges Porifera of the Mariana Islands. Micronesica 2003, 35: 100–120.

Kinsey DW, Kinsey E: Diurnal changes in oxygen content of the water over the coral reef platform at Heron I. Mar Freshw Res 1967, 18: 23–34. 10.1071/MF9670023

Knowlton N, Jackson JB: Shifting baselines, local impacts, and global change on coral reefs. PLoS Biol 2008, 6: e54. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060054

Koehl MAR: Water flow and the morphology of zoanthid colonies. Proc 3rd Int Coral Reef Symp 1977, 1: 437–444.

Kohler KE, Gill SM: Coral Point Count with Excel extensions CPCe: a visual basic program for the determination of coral and substrate coverage using random point count methodology. Comput Geosci 2006, 32: 1259–1269. 10.1016/j.cageo.2005.11.009

Legendre P: R functions. Université de Montréal Département de sciences biologiques; 2005. . Accessed 1 April 2013 http://adn.biol.umontreal.ca/~numericalecology/Rcode/

Legendre P, Gallagher ED: Ecologically meaningful transformations for ordination of species data. Oecologia 2001, 129: 271–280. 10.1007/s004420100716

Legendre P, Legendre L: Numerical ecology. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science BV; 2012.

Liao MH, Tang SL, Hsu CM, Wen KC, Wu H, Chen WM, Wang JT, Meng PJ, Twan WH, Lu CK, Dai CF, Soong K, Chen CA: The“black disease” of reef-building corals at Green Island, Taiwan - outbreak of a cyanobacteriosponge, Terpios hoshinota (Suberitidae; Hadromerida). Zool Stud 2007, 46: 520.

Loya Y: The coral reefs of Eilat - past, present and future: three decades of coral community structure studies. In Coral reef health and disease. Edited by: Rosenberg E, Loya Y. Berlin: Springer; 2004:29.

Loya Y, Sakai K, Yamasato K, Nakano Y, Sambali H, van Woesik R: Coral bleaching: the winners and the losers. Ecol Lett 2001, 4: 122–131. 10.1046/j.1461-0248.2001.00203.x

McClanahan T, Polunin N, Done T: Ecological states and the resilience of coral reefs. Conserv Ecol 2002, 6: 18.

Meng PJ, Lee HJ, Wang JT, Chen CC, Lin HJ, Tew KS, Hsieh WJ: A long-term survey on anthropogenic impacts to the water quality of coral reefs, southern Taiwan. Environ Pollut 2008, 156: 67–75. 10.1016/j.envpol.2007.12.039

Morton B: Hong Kong's coral communities: status, threats and management plans. Mar Pollut Bull 1994, 29: 74–83. 10.1016/0025-326X(94)90429-4

Nairn O: Seasonal responses of a fringing reef community to eutrophication (Reunion Island, Western Indian Ocean). Mar Ecol Prog Ser 1993, 99: 137–151.

Neter J, Kutner MH, Nachtsheim CJ, Wasserman W: Applied linear statistical models, vol 4. Chicago: Irwin; 1996:1048.

Ramos AA, Inoue Y, Ohde S: Metal contents in Porites corals: anthropogenic input of river run-off into a coral reef from an urbanized area, Okinawa. Mar Pollut Bull 2004, 483: 281–294.

Rao CR: A review of canonical coordinates and an alternative to correspondence analysis using Hellinger distance. Questiió: Quaderns d'Estadística, Sistemes, Informatica i Investigació Operativa 1995, 19: 23–63.

Reimer AA: Feeding behavior in the Hawaiian zoanthids Palythoa and Zoanthus . Pac Sci 1971, 25: 512–520.

Reimer AA: Observations on the relationships between several species of tropical zoanthids (Zoanthidea, Coelenterata) and their zooxanthellae. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 1971, 7: 207–214. 10.1016/0022-0981(71)90032-3

Reimer JD, Takishita K, Maruyama T: Molecular identification of symbiotic dinoflagellates ( Symbiodinium spp.) from Palythoa spp. (Anthozoa: Hexacorallia) in Japan. Coral Reefs 2006, 25: 521–527. 10.1007/s00338-006-0151-4

Reimer JD, Mizyama M, Nakano M, Fujii T, Hirose E: Current status of the distribution of the coral-encrusting cyanobacteriosponge Terpios hoshinota in southern Japan. Galaxea 2011, 131: 35–44.

Reimer JD, Nozawa Y, Hirose E: Domination and disappearance of the black sponge: a quarter century after the initial Terpios outbreak in southern Japan. Zool Stud 2011, 50: 394.

Roberts CM, McClean CJ, Veron JE, Hawkins JP, Allen GR, McAllister DE, Mittermeier CG, Schueler FW, Spalding M, Wells F, Vynne C, Werner TB: Marine biodiversity hotspots and conservation priorities for tropical reefs. Science 2002,295(5558):1280–1284. 10.1126/science.1067728

Rützler K, Muzik K: Terpios hoshinota , a new cyanobacteriosponge threatening Pacific reefs. Sci Mar (Barcelona) 1993, 57: 395–403.

Sakai K, Nishihira M: Immediate effect of terrestrial runoff on a coral community near a river mouth in Okinawa. Galaxea 1991, 10: 125–134.

Sebens KP: Intertidal distribution of zoanthids on the Caribbean coast of Panama: effects of the predation and desiccation. B Mar Sci 1982, 32: 316–335.

Suchanek TH, Green DJ: Interspecific competition between Palythoa caribaeorum and other sessile invertebrates on St. Croix reefs, US Virgin Islands. Proc 4th Int Coral Reef Symp 1981, 2: 679–684.

Szmant AM: Nutrient enrichment on coral reefs: is it a major cause of coral reef decline? Estuaries 2002, 25: 743–766. 10.1007/BF02804903

van Woesik R, Irikawa A, Loya Y: Coral bleaching: signs of change in southern Japan. In Coral health and disease. Edited by: Loya Y, Rosenberg E. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2004:p119–141.

van Woesik R, Sakai K, Ganase A, Loya Y: Revisiting the winners and the losers a decade after coral bleaching. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 2011, 434: 67–76.

Ward-Paige CA, Risk MJ, Sherwood OA, Jaap WC: Clionid sponge surveys on the Florida Reef Tract suggest land-based nutrient inputs. Mar Pollut Bull 2005, 51: 570–579. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2005.04.006

Weil E, Hernandez-Delgado EA, Bruckner AW, Ortiz AL, Nemeth M, Ruiz H: Distribution and status of acroporid coral Scleractinia populations in Puerto Rico. In NOAA Tech Memo NMFS-OPR-24. Edited by: Bruckner AW. MD: Silver Spring; 2002:71–98.

West K, van Woesik R: Spatial and temporal variance of river discharge on Okinawa Japan: inferring the temporal impact on adjacent coral reefs. Mar Pollut Bull 2001, 42: 864–872. 10.1016/S0025-326X(01)00040-6

Wilkinson CR: Status of the coral reefs of the world: 2008. Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network and Australian Institute of Marine. Townsville: Science; 2008.

Work TM, Aeby GS, Maragos JE: Phase shift from a coral to a corallimorph-dominated reef associated with a shipwreck on Palmyra Atoll. PLoS ONE 2008, 3: e2989. 10.1371/journal.pone.0002989

Yamazato K: Coral bleaching in Okinawa, 1980 vs 1998. Galaxea 1999, 1: 83–87.

Zuur AF, Ieno EN, Elphick CS: A protocol for data exploration to avoid common statistical problems. Meth Ecol Evol 2010, 1: 3–14. 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2009.00001.x

Acknowledgements

We thank Javier Montenegro for helping set up the survey locations and for the additional support from members of the Molecular Invertebrate Systematics and Ecology (MISE) Laboratory, Prof. Shoichiro Suda, Prof. Makoto Tsuchiya, Izumi Mimura (all from University of the Ryukyus). We are also thankful to Dr. Holger Jenke-Kodama, Dr. Maiko Tamura, and other members of the Jenke-Kodama Unit from Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST) for their help with water analyses. We also thank Chao-Yang Kuo (James Cook University) and Aichi Chung (Academia Sinica) for providing information and helping with analyses. The senior author was funded in part by the Rising Star Program and the International Research Hub Project for Climate Change and Coral Reef/Island Dynamics, both at the University of the Ryukyus. Lastly, we thank the two anonymous reviewers' comments that greatly improved this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests in this research.

Authors' contributions

SYY, CDA, and JDR designed and set up the research. SYY and CDA carried out all the survey and sampling. SYY and CB performed the data analyses. SYY, CB, and JDR wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, SY., Bourgeois, C., Ashworth, C.D. et al. Palythoa zoanthid 'barrens’ in Okinawa: examination of possible environmental causes. Zool. Stud. 52, 39 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1810-522X-52-39

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1810-522X-52-39