Abstract

Background

Fluids are often given liberally after the return of spontaneous circulation. However, the optimal fluid regimen in survivors of cardiac arrest is unknown. Recent studies indicate an increased fluid requirement in post-cardiac arrest patients. During hypothermia, animal studies report extravasation in several organs, including the brain. We investigated two fluid strategies to determine whether the choice of fluid would influence fluid requirements, capillary leakage and oedema formation.

Methods

19 survivors with witnessed cardiac arrest of primary cardiac origin were allocated to either 7.2% hypertonic saline with 6% poly (O-2-hydroxyethyl) starch solution (HH) or standard fluid therapy (Ringer's Acetate and saline 9 mg/ml) (control). The patients were treated with the randomised fluid immediately after admission and continued for 24 hours of therapeutic hypothermia.

Results

During the first 24 hours, the HH patients required significantly less i.v. fluid than the control patients (4750 ml versus 8010 ml, p = 0.019) with comparable use of vasopressors. Systemic vascular resistance was significantly reduced from 0 to 24 hours (p = 0.014), with no difference between the groups. Colloid osmotic pressure (COP) in serum and interstitial fluid (p < 0.001 and p = 0.014 respectively) decreased as a function of time in both groups, with a more pronounced reduction in interstitial COP in the crystalloid group. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain did not reveal vasogenic oedema.

Conclusions

Post-cardiac arrest patients have high fluid requirements during therapeutic hypothermia, probably due to increased extravasation. The use of HH reduced the fluid requirement significantly. However, the lack of brain oedema in both groups suggests no superior fluid regimen. Cardiac index was significantly improved in the group treated with crystalloids. Although we do not associate HH with the renal failures that developed, caution should be taken when using hypertonic starch solutions in these patients.

Trial registration

NCT00347477.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Few studies have described fluid requirements in cardiac arrest patients [1–3], but fluid infusion after ROSC is increasingly debated [4]. During hypothermia, animal studies report extravasation in several organs, including the brain [5, 6]. Whether capillary leakage is present in man during therapeutic hypothermia, is not documented. This is of clinical interest, as oedema formation in a vulnerable OHCA-brain is considered harmful. Furthermore, this is underlined by the similarity between post-resuscitation syndrome and sepsis [7, 8]. Septic patients are known to have high fluid requirements, and outcome is improved by goal-directed fluid therapy [9]. Encouraged by the low cardiac output after cardiac arrest [1], fluid load would appear to be worth attempting. In addition, the induction of hypothermia by large volumes of cold intravenous infusions has gained in popularity [10].

The application of a hypertonic colloid during cardiopulmonary bypass has been shown to reduce fluid overload [11, 12]. Colloids tend to cause less tissue oedema than crystalloids [13] and, as regards inflammatory-related leakages, hydroxyethyl starch could have an 'occlusive' effect on damaged capillaries, subsequently limiting extravasation [14]. Furthermore, hypertonic solutions recruit fluid from the intracellular space to the capillaries, and, during CPR in an animal model, these solutions increased myocardial blood flow and the survival rate [15].

The aim of the study was to determine whether a capillary leakage was present in OHCA survivors during therapeutic hypothermia. We compared two fluid regimens and studied the impact on capillary leakage. The intervention group received an additional 500 ml of 7.2% hypertonic saline with 6% poly (O-2-hydroxyethyl) starch solution during the first 24 hours, and was compared with standard therapy. The primary endpoint was the amount of fluid administered during the first 24 hours. The secondary endpoint was the magnitude of capillary leakage as a surrogate marker for oedema formation.

Methods

Ethics

The study was approved by the Regional Committees for Medical Research Ethics, the Data Inspectorate, the Directorate for Health and Social Affairs and the Norwegian Medicines Agency. Deferred consent was used, and the patients' families were entitled to withdraw the patients at any time. All patients included were informed about the study when they were able to receive the information and signed a written informed consent form.

Study population and environment

The study was performed on 19 patients with witnessed out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) and carried out between September 2005 and March 2007 at Haukeland University Hospital (Bergen, Norway), an 1,100-bed hospital serving 600,000 people. All inclusion/exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1. The fluid intervention was initiated immediately after admission to the emergency room and continued for the first 24 hours.

Treatment protocol

On admission, the patients were allocated by means of stratified randomisation to one of two fluid regimens administered via infusion pumps: Ringer's Acetate and saline 9 mg/ml (control), or hypertonic colloid,7.2% NaCl with 6% Hydroxyethyl starch 200/0.5 (HyperHAES® Fresenius Kabi, Germany) (HH). Fluid was administered to achieve the treatment goals listed in Table 2. HH was limited to 500 ml per 24 hours (20 ml/hr). Further needs for fluid in the HH group were met by Ringer's Acetate/saline 9 mg/ml. The control group received Ringer's Acetate and saline 9 mg/ml by turn during the observation period, in accordance with the standard treatment in the medical intensive care unit (MICU).

Coronary intervention

Patients with ST elevation, a new left bundle branch block or cardiogenic shock were referred immediately for coronary angiography and subsequent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Magnetic resonance imaging

Before admission to the MICU, after cardiac intervention and if the patient did not have an intra-aortic-balloon pump (IABP), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was planned (1.5 Tesla, conventional morphological and diffusion sequences). Repeated MRI was scheduled after 24 and 96 hours.

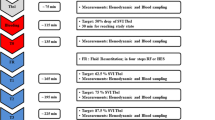

Intensive care treatment and monitoring

Cardiac arrest data were recorded according to the Utstein style [16]. In the MICU, monitoring was performed (IntelliVue, Philips, Eindhoven, the Netherlands) with continuous ECG, arterial pressure and continuous cardiac output registration (PiCCO®, Pulsion Medical System AG, Germany). Fluid balance was measured as the total amount of fluid administered intravenously and enterally in relation to output measured by hourly diuresis and 24-hour faecal loss. Systemic vascular resistance (SVR) was calculated 0, 8, 16 and 24 hours after admission to the MICU. Vasopressors (dopamine, noradrenaline, and adrenaline) were administered if the mean arterial blood pressure was <60 mmHg and the fluid load proved ineffective, guided by PiCCO measurements. Dopamine was replaced with noradrenaline if tachycardia occurred (>100 beats min-1) or if dopamine failed to achieve the required blood pressure. Sedatives (midazolam, alfentanil) were administered to achieve a motor activity assessment score of 0 (MAAS). If necessary, vecuronium was administered to prevent shivering. Ventilation was provided by Evita XL (Dräger Medical, Lübeck, Germany), using a bi-positive airway pressure mode. Cooling was initiated outside the hospital for all patients who had return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) and remained unconscious. At the scene, cooling was performed using icepacks placed on the neck, armpits and groin. A Coolgard catheter (Alsius, California, USA) was installed in the right femoral vein in the PCI lab and activated in the MICU, cooling the patient at a rate of 1°C per hour. The target temperature was set at 33°C and measured in the urine bladder. After 24 hours of cooling, rewarming at a rate of 0.5°C per hour was stopped at 35.0°C.

Blood samples and sampling of interstitial fluid

Blood samples were taken from the artery line after 0, 8, 16 and 24 hours, and analysed at the Laboratory of Clinical Biochemistry at Haukeland University Hospital. Colloid osmotic pressure (COP) was measured at 0, 8, 16 and 24 hours in serum and in interstitial fluid that was sampled using the wick method, installed for 60 minutes [17–20]. A sterile, multi-filament nylon wick was soaked in Ringer AC. Using a sterile technique and a needle, the wick was placed subcutaneously in the midaxillary line. Three wicks were installed at intervals of 3 cm and covered by plastic film (Tegaderm, 3M Inc., Canada), to prevent evaporation. COP was measured by means of a transducer (Gould-Statham, Spectramed, USA), recorded and amplified with an EasyGraph 240 (Gould Inc., USA).

Statistical analysis

The randomisation was stratified with respect to initial heart rhythm. Numbered envelopes were distributed from the MICU and opened when the physician in the emergency room enrolled a patient, filling in the inclusion criteria. The allocation was generated by the authors. The sample size was determined by power calculations on the basis of a required volume load of 8000 ml crystalloids during the first 24 hours and a standard deviation of 500 ml. A power of 80% and a significance level of 0.05 for a two sample t-test suggested that it would be sufficient to have three patients in each group if HH reduced the required volume by 30% to 5600 ml. Due to lower power in non-parametric tests, a higher number was chosen. The unconscious patients, as well as the neuroradiologist, were blinded to the treatment. The two treatment groups were descriptively compared at baseline. Fluid load, urine output and fluid balance were compared using an exact Mann-Whitney test. Mixed effects models were used for group comparisons of repeated measurements of variables [21]. Time from baseline was entered as a categorical covariate, as well as any differences in developments in the two groups, and there were assumed to be no group differences at baseline. The nlme package in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was used for linear mixed effects models; SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for other statistical analyses, and SPSS Sample Power for power calculation. Numbers were presented as mean (standard error), or median (low-high). A p-value <0.05 was considered significant. For categorical covariates with more than two categories, both overall p-values for the variable and p-values for individual contrasts are reported.

Results

Patients and outcome

Twenty-four patients were randomised. Five were excluded due to lack of witnessed arrest, inclusion in another study, probable respiratory cause of the cardiac arrest, and age >80 years (Fig 1). Ten patients (two female) were randomised to HH, and nine (one female) to the control fluid regimen. The initial heart rhythms and baseline characteristics are presented in Table 3. There were no substantial differences between the groups as regards the aetiology of the arrest. The first temperature recorded at the hospital was 34.5 (1.4) °C. Survival after one year was 79%, with no significant difference between the groups (Table 3).

Fluid

During the first 24 hours in the hospital, the HH group required significantly less fluid than the control group to meet the treatment goals. Fluid calculations are presented in Table 4. The HH group received 6.02 ml/kg (4.63 - 7.69) of HH during the first 24 hours.

Oedema

COP in plasma showed a significant decline in both groups (Fig. 2a). The reduction was more rapid in the control than in the HH group, but the nadir levels were the same in both groups. The corresponding levels of interstitial COP showed the same pattern (Fig. 2b). The drop in COP was significant at all times, except for the HH group at eight hours. The planned MRI at 0, 24 and 96 hours was performed on seven patients. MRI was performed at 0 and 96 hours on two patients, and on one patient at 96 hours. The ten patients were equally distributed between the two groups. Divergence from the plan was due to technical problems. MRI did not reveal vasogenic cerebral oedema in any of these patients.

Colloid osmotic pressure during cooling. Mixed effects model with mean and standard error.

a) Colloid osmotic pressure in plasma. Mixed effects model with mean and standard error. Overall p < 0.001. Changes 24 vs. 0 hours. p < 0.001 (both groups). b) Colloid osmotic pressure in interstitial tissue. Mixed effects model with mean and standard error. Overall p < 0.001. Changes 24 vs. 0 hours. p = 0.001/p < 0.001 (HH/Control).

Hemodynamics

SVR dropped significantly in both groups (Fig. 3). The cardiac index (CI) was 2.2 l/min/m2 (0.2) on admission to the MICU. At 24 hours, before rewarming, the CI was higher in both groups and significantly higher in the control group (Fig. 4). MAP and CVP did not differ significantly between groups (Fig. 5). There were no differences in dose and type of vasopressors between the groups. All patients needed vasopressors, primarily dopamine in accordance with the MICU guidelines.

Laboratory data/adverse effects

All laboratory data are listed in Table 5. Serum osmolality differed significantly, with an increase in the HH group and a decrease in the control group (p < 0.001). Serum sodium and chloride increased in both groups. Two patients who received HH later developed renal failure.

Discussion

We studied fluid requirements and oedema formation in survivors of OHCA in a prospective, randomised design. The HH patients received significantly less fluid than the control patients (4750 ml vs. 8010 ml, p = 0.019). Both groups had a significant drop in SVR, and demonstrated increased extravasation through the drop in COP. The extravasation did not show as vasogenic brain oedema.

The strength of the study lies in its design and the multiple determination of leakage. The weakness of our design is that the treating physicians were not blinded. This could have caused a tendency to replace fluid with vasopressors. However, there were no differences between the groups regarding the use of these drugs. Furthermore, as sedation can cause vasodilatation, the use of sedation may influence the use of fluid and vasopressors. The lowest doses of sedation were used in all patients to achieve MAAS 0-1. The number of patients in our study is not sufficient to determine whether fluid load can affect neurological outcome/survival.

A large cohort study recently reported on the challenging aspects of therapeutic hypothermia [22]. In spite of a positive fluid balance, many patients appear to be hypovolemic and have high fluid requirements [2]. Our reported fluid balance is slightly higher than the balance reported by Sunde and colleagues, who found a positive balance of 3455 ml (1594) during 24 hours with similar treatment goals [3]. Laurent and colleagues used 3500-6500 ml during the first 24 hours to maintain an adequate filling pressure in normothermic cardiac arrest patients [1]. Whether reduced fluid load is of benefit to these patients remains unknown.

To our knowledge, there are no papers describing repetitive MRI in the initial treatment of OHCA patients. Järnum and colleagues performed MRI on 20 cardiac arrest patients who remained unconscious 72 hours after normothermia [23]. They found hypoxic-ischemic cerebral oedema in two patients during neuropathological examination post mortem. None of the patients in our study had a vasogenic cerebral oedema on the MRI, which indicated an intact blood-brain barrier. Animal studies have shown that asphyxia is more likely to cause a disrupted blood-brain barrier [24–26]. The lack of vasogenic oedema may be the result of cardiac origin of the arrest, the fact that arrests were witnessed and short time before initiation of CPR.

We found reduced fluid leakage to the interstitial space in the HH patients compared with controls. Maintenance of intravascular COP is one important factor in determining fluid flux across the capillary membrane. The decline in COP in plasma was probably due to hemodilution, which is also reflected in a reduction in haemoglobin and erythrocyte volume fraction.

The reduction in COP in interstitial fluid is probably caused by the escape of fluid with a lower COP through the capillaries. Since we observed a simultaneous reduction in COP both in plasma and interstitial fluid, the increased extravasation cannot be explained by the differences in the COP gradient between the groups. However, the change may be attributed instead to capillary leakage, which has also been demonstrated in several animal studies [5, 27, 28]. This is supported by Nordmark et al., who found a decreased intravascular volume during hypothermia after cardiac arrest [2]. COP is important in capillary fluid exchange, but is a minor component of the total osmotic pressure. The significant difference between the groups regarding serum osmolality may partly explain the observed differences in fluid loads. This emphasises the importance of also taking the total osmotic pressure into consideration when choosing i.v. fluid. Sodium concentration in the HH group differed significantly from the controls after 24 hours and reflected the content of sodium in the HH solution. This may influence fluid shifts and lead to osmotic dehydration, with shrinkage of cells and the prevention of endothelial oedema [29].

Both groups demonstrated a comparable and significant reduction in SVR, suggesting a similarity between septic and post-cardiac arrest patients [30]. As hypovolemia leads to an increased SVR, our finding may reflect a volume 'overload' [31]. Hypothermia and infusion of vasopressors should induce vasoconstriction and centralise circulation. However, intravenous fluid and inflammation counteract vasoconstriction [32], and the overall result was a significant decline in SVR in both the study and the control group, also observed by Laurent et al. [1].

Small volume resuscitation with hypertonic saline during CPR is described as feasible and safe [29], and, in a study of critically ill ICU patients, HH was infused without negative effects on renal function [33]. The VISEP study [34] showed impaired renal function in sepsis patients resuscitated with hydroxyethyl starch 200/0.5, and there have been discussions concerning the safety of these solutions in critically ill patients. Two of our patients who received HH developed renal failure, one due to arterial embolism, while the other developed failure weeks later. We consider the kidney failure in these two patients to be unrelated to HH; its contribution cannot be excluded, however.

Despite lower body temperature, CI was higher at 24 hours than on admission to the MICU. The increase was significant in the control group. Laurent and collaborators made the same observation when they monitored more than 160 OHCA patients with pulmonary artery catheter [1]. The improvement in CI in our study represents adequate fluid load and reduced stunning of the heart. In a recent study, Jacobshagen et al. also demonstrated an improved ventricular function over time in patients after cardiac arrest [35].

The clinical implication of the present study is that post-cardiac arrest patients can be liberally infused with crystalloids during the first 24 hours without cerebral oedema resulting. They also have a high fluid requirement, which is partly because of increased extravasation, measured by means of colloid osmotic pressures, systemic vascular resistance and fluid calculations. Both fluid regimens stabilise hemodynamics. The reduced fluid load achieved by the application of HH should be further investigated in cardiac arrest caused by asphyxia, where a disrupted blood-brain barrier is more likely. The lack of vasogenic brain oedema in these patients is encouraging. This supports a liberal use of crystalloids, especially due to an increased need for intravascular volume and the possible side effects of colloids. Furthermore, the impact on neurological outcome and survival should be examined.

Conclusions

Post-cardiac arrest patients have high fluid requirements during therapeutic hypothermia, probably due to increased extravasation. The use of HH reduced the fluid requirement significantly. However, the lack of brain oedema in both groups suggests no superior fluid regimen. Cardiac index was significantly improved in the group treated with crystalloids. Although we do not associate HH with the renal failures that developed, caution should be taken when using hypertonic starch solutions in these patients.

References

Laurent I, Monchi M, Chiche JD, Joly LM, Spaulding C, Bourgeois B, Cariou A, Rozenberg A, Carli P, Weber S, Dhainaut JF: Reversible myocardial dysfunction in survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002, 40: 2110-2116. 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)02594-9.

Nordmark J, Johansson J, Sandberg D, Granstam SO, Huzevka T, Covaciu L, Mörtberg E, Rubertsson S: Assessment of intravascular volume by transthoracic echocardiography during therapeutic hypothermia and rewarming in cardiac arrest survivors. Resuscitation. 2009, 80: 1234-1239. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.06.035.

Sunde K, Pytte M, Jacobsen D, Mangschau A, Jensen LP, Smedsrud C, Draegni T, Steen PA: Implementation of a standardised treatment protocol for post resuscitation care after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2007, 73: 29-39. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.08.016.

Soar J, Foster J, Breitkreutz R: Fluid infusion during CPR and after ROSC--is it safe?. Resuscitation. 2009, 80: 1221-1222. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.09.014.

Hammersborg SM, Brekke HK, Haugen O, Farstad M, Husby P: Surface cooling versus core cooling: Comparative studies of microvascular fluid- and protein-shifts in a porcine model. Resuscitation. 2008, 79: 292-300. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.06.008.

Hammersborg SM, Farstad M, Haugen O, Kvalheim V, Onarheim H, Husby P: Time course variations of haemodynamics, plasma volume and microvascular fluid exchange following surface cooling: an experimental approach to accidental hypothermia. Resuscitation. 2005, 65: 211-219. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.11.020.

Negovsky VA: Postresuscitation disease. Crit Care Med. 1988, 16: 942-946. 10.1097/00003246-198810000-00004.

Nolan JP, Neumar RW, Adrie C, Aibiki M, Berg RA, Bottiger BW, Callaway C, Clark RS, Geocadin RG, Jauch EC, Kern KB, Laurent I, Longstreth WT, Merchant RM, Morley P, Morrison LJ, Nadkarni V, Peberdy MA, Rivers EP, Rodriguez-Nunez A, Sellke FW, Spaulding C, Sunde K, Hoek TV: Post-cardiac arrest syndrome: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and prognostication A Scientific Statement from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation; the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee; the Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Perioperative, and Critical Care; the Council on Clinical Cardiology; the Council on Stroke. Resuscitation. 2008, 79: 350-379. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.09.017.

Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B, Peterson E, Tomlanovich M, Early Goal-Directed Therapy Collaborative Group: Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001, 345: 1368-1377. 10.1056/NEJMoa010307.

Behringer W, Arrich J, Holzer M, Sterz F: Out-of-hospital therapeutic hypothermia in cardiac arrest victims. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2009, 17: 52-10.1186/1757-7241-17-52.

Kvalheim V, Farstad M, Haugen O, Brekke H, Mongstad A, Nygreen E, Husby P: A hyperosmolar-colloidal additive to the CPB-priming solution reduces fluid load and fluid extravasation during tepid CPB. Perfusion. 2008, 23: 57-63. 10.1177/0267659108094364.

Kvalheim VL, Farstad M, Steien E, Mongstad A, Borge BA, Kvitting PM, Husby P: Infusion of hypertonic saline/starch during cardiopulmonary bypass reduces fluid overload and may impact cardiac function. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2010, 54: 485-93. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.02156.x.

Weil MH, Henning RJ, Puri VK: Colloid oncotic pressure: clinical significance. Crit Care Med. 1979, 7: 113-116. 10.1097/00003246-197903000-00006.

Vincent JL: Plugging the leaks? New insights into synthetic colloids. Crit Care Med. 1991, 19: 316-318. 10.1097/00003246-199103000-00051.

Fischer M, Dahmen A, Standop J, Hagendorff A, Hoeft A, Krep H: Effects of hypertonic saline on myocardial blood flow in a porcine model of prolonged cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2002, 54: 269-280. 10.1016/S0300-9572(02)00151-X.

Cummins RO, Chamberlain DA, Abramson NS, Allen M, Baskett PJ, Becker L: Recommended guidelines for uniform reporting of data from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: the Utstein Style. A statement for health professionals from a task force of the American Heart Association, the European Resuscitation Council, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, and the Australian Resuscitation Council. Circulation. 1991, 84: 960-975.

Aukland K, Fadnes HO: Protein concentration of interstitial fluid collected from rat skin by a wick method. Acta Physiol Scand. 1973, 88: 350-358. 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1973.tb05464.x.

Aukland K, Johnsen HM: A colloid osmometer for small fluid samples. Acta Physiol Scand. 1974, 90: 485-490. 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1974.tb05611.x.

Fadnes HO, Aukland K: Protein concentration and colloid osmotic pressure of interstitial fluid collected by the wick technique: analysis and evaluation of the method. Microvasc Res. 1977, 14: 11-25. 10.1016/0026-2862(77)90137-6.

Noddeland H: Colloid osmotic pressure of human subcutaneous interstitial fluid sampled by nylon wicks: evaluation of the method. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1982, 42: 123-130.

Pinheiro J, Bates D: Mixed effects model in S and S-plus. 2000, New York: Springer

Nielsen N, Hovdenes J, Nilsson F, Rubertsson S, Stammet P, Sunde K, Valsson F, Wanscher M, Friberg H, Hypothermia Network: Outcome, timing and adverse events in therapeutic hypothermia after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009, 53: 926-934. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.02021.x.

Jarnum H, Knutsson L, Rundgren M, Siemund R, Englund E, Friberg H, Larsson EM: Diffusion and perfusion MRI of the brain in comatose patients treated with mild hypothermia after cardiac arrest: a prospective observational study. Resuscitation. 2009, 80: 425-430. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.01.004.

Iida K, Satoh H, Arita K, Nakahara T, Kurisu K, Ohtani M: Delayed hyperemia causing intracranial hypertension after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Crit Care Med. 1997, 25: 971-976. 10.1097/00003246-199706000-00013.

Morimoto Y, Kemmotsu O, Kitami K, Matsubara I, Tedo I: Acute brain swelling after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: pathogenesis and outcome. Crit Care Med. 1993, 21: 104-110. 10.1097/00003246-199301000-00020.

Torbey MT, Selim M, Knorr J, Bigelow C, Recht L: Quantitative analysis of the loss of distinction between gray and white matter in comatose patients after cardiac arrest. Stroke. 2000, 31: 2163-2167.

Farstad M, Haugen O, Kvalheim VL, Hammersborg SM, Rynning SE, Mongstad A, Nygreen E, Husby P: Reduced fluid gain during cardiopulmonary bypass in piglets using a continuous infusion of a hyperosmolar/hyperoncotic solution. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006, 50: 855-862. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.01064.x.

Farstad M, Heltne JK, Rynning SE, Onarheim H, Mongstad A, Eliassen F, Husby P: Can the use of methylprednisolone, vitamin C, or alpha-trinositol prevent cold-induced fluid extravasation during cardiopulmonary bypass in piglets?. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004, 127: 525-534. 10.1016/S0022-5223(03)01028-6.

Bender R, Breil M, Heister U, Dahmen A, Hoeft A, Krep H, Fischer M: Hypertonic saline during CPR: Feasibility and safety of a new protocol of fluid management during resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2007, 72: 74-81. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.05.019.

Adrie C, Laurent I, Monchi M, Cariou A, Dhainaou JF, Spaulding C: Postresuscitation disease after cardiac arrest: a sepsis-like syndrome?. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2004, 10: 208-212. 10.1097/01.ccx.0000126090.06275.fe.

Isakow W, Schuster DP: Extravascular lung water measurements and hemodynamic monitoring in the critically ill: bedside alternatives to the pulmonary artery catheter. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006, 291: L1118-1131. 10.1152/ajplung.00277.2006.

Di Lorenzo A, Fernandez-Hernando C, Cirino G, Sessa WC: Akt1 is critical for acute inflammation and histamine-mediated vascular leakage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009, 106: 14552-14557. 10.1073/pnas.0904073106.

Boldt J, Muller M, Mentges D, Papsdorf M, Hempelmann G: Volume therapy in the critically ill: is there a difference?. Intensive Care Med. 1998, 24: 28-36. 10.1007/s001340050511.

Brunkhorst FM, Engel C, Bloos F, Meier-Hellmann A, Ragaller M, Weiler N, Moerer O, Gruendling M, Oppert M, Grond S, Olthoff D, Jaschinski U, John S, Rossaint R, Welte T, Schaefer M, Kern P, Kuhnt E, Kiehntopf M, Hartog C, Natanson C, Loeffler M, Reinhart K, German Competence Network Sepsis (SepNet): Intensive insulin therapy and pentastarch resuscitation in severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2008, 358: 125-139. 10.1056/NEJMoa070716.

Jacobshagen C, Pax A, Unsold BW, Seidler T, Schmidt-Schweda S, Hasenfuss G, Maier LS: Effects of large volume, ice-cold intravenous fluid infusion on respiratory function in cardiac arrest survivors. Resuscitation. 2009, 80: 1223-1228. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.06.032.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Professor Kjetil Sunde for his comments on the manuscript, and the nurses in the MICU for excellent work and a positive attitude. The study was supported by a research grant from the Regional Centre for Emergency Medical Research and Development (RAKOS, Stavanger/Norway) and Section of Emergency Medicine, Dept. of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, Haukeland University Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

BEH participated in the design of the study, the application for official approvals and the collection and interpretation of data. JKH, ABG participated in the design of the study and in collection and interpretation of data. JL, RF participated in the design of the study and collection of data. SMH, EML participated in the collection and interpretation of data. TWL participated in the design of the study and statistical analysis of the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Heradstveit, B.E., Guttormsen, A.B., Langørgen, J. et al. Capillary leakage in post-cardiac arrest survivors during therapeutic hypothermia - a prospective, randomised study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 18, 29 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-7241-18-29

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-7241-18-29