Abstract

Background

Evaluate and compare the utility of serum folate receptor alpha (FRA) and megakaryocyte potentiating factor (MPF) determinations relative to serum CA125, mesothelin (MSLN) and HE4 for the diagnosis of epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC).

Methods

Electrochemiluminescent assays were developed for FRA, MSLN and MPF and used to assess the levels of these biomarkers in 258 serum samples from ovarian cancer patients. Commercial assays for CA125 and HE4 were run on a subset of 176 of these samples representing the serous histology. Data was analyzed by histotype, stage and grade of disease. A comparison of the levels of the FRA, MSLN and MPF biomarkers in serum, plasma and urine was also performed in a subset of 57 patients.

Results

Serum and plasma levels of FRA, MSLN and MPF were shown to be highly correlated between the two matrices. Correlations between all pairs of markers in 318 serum samples were calculated and demonstrated the highest correlation between HE4 and MPF, and the lowest between FRA and MPF. Serum levels of all markers showed a dependence on both stage and grade of disease. A multi-marker logistic regression model was developed resulting in an AUC=0.91 for diagnosis of serous ovarian cancer, a significant improvement over the AUC for any of the individual markers, including CA125 (AUC=0.84).

Conclusions

FRA has significant potential as a biomarker for ovarian cancer, both as a stand-alone marker and in combination with other known markers for EOC. The lack of correlation between the various markers analyzed in the present study suggests that a panel of markers can aid in the detection and/or monitoring of this disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In 2012, it is estimated that 22,280 women will be diagnosed with ovarian cancer and 15,500 will die of the disease (SEER fact sheet). Ovarian cancer is considered a “silent killer” because of the absence of specific symptoms until late in the disease when 75% of the cases are diagnosed, five year survival rates are less than 30%, and a 70% recurrence rate is expected. Early diagnosis, when the cancer is confined to the ovary, can increase the 5-year survival rate to 90%. Because of the high fatality rate and relatively low prevalence of the disease, a sensitive and specific screening tool for asymptomatic women is needed. As such, effective and reliable diagnostic assays need to be highly sensitive and specific for the screening and detection of early stage ovarian cancer, especially in asymptomatic women.

CA125, a membrane-associated mucin found on the apical membrane of epithelial cells of the ocular surface, respiratory tract and female reproductive tract, is elevated in approximately 80% of women with late-stage ovarian cancer. It is the gold standard diagnostic marker to detect recurrent ovarian cancer and monitor response to treatment. However, the usefulness of CA125 as a marker cannot be extended to diagnosis as 20% of ovarian cancers do not express CA125 [1], and elevated levels are detected in only half of early stage patients. Further, CA125 is detected in many benign gynecological conditions and is particularly unreliable in detecting ovarian cancer in premenopausal women [2–5]. Additional biomarkers with high sensitivity and specificity for detecting ovarian cancer in the early stages of the disease are sought to complement CA125. Two promising markers are human epididymis protein 4 (HE4) and mesothelin (MSLN). CA125, HE4 and MSLN have been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as biomarkers for recurrent ovarian cancer (CA125 and HE4) and diagnosis of mesothelioma (MSLN).

Human epididymis protein 4 (HE4), normally expressed in the epididymis, endometrial glands and respiratory tract [6, 7], is up-regulated in both early and late stage ovarian cancer [6–9] including 90% of serous carcinoma, and adenocarcinomas of the lung and endometrium [10, 11]. It is not expressed in mucinous carcinoma [12]. It has been widely studied as a biomarker, alone and in combination with CA125, for the diagnosis and monitoring of recurrent disease as little or no expression is observed in benign conditions [8, 10, 13, 14]. When combined, HE4 has been shown to increase the sensitivity and specificity over CA125 alone [2, 9, 11, 15], allowing for better detection of early stage ovarian cancer [9, 15]. HE4 levels have, however, been shown to increase with age [16].

Soluble mesothelin (MSLN) has a history as a biomarker for mesothelioma diagnosis, prognosis and monitoring [17–19]. It is a differentiating antigen derived from a precursor protein that when cleaved yields Megakaryocyte Potentiating Factor (MPF), a 32 kDa excreted soluble protein [20, 21], and MSLN, a 40 kDa GPI-linked glycoprotein that is also shed as a soluble form into the blood stream by frameshift mutation and proteolytic cleavage [22, 23]. MSLN is hypothesized to be involved in cell adhesion and signaling [24] and to contribute to the metastasis of ovarian cancer to the peritoneum by binding CA125 [25, 26]. It is highly expressed in mesothelioma, ovarian and pancreatic cancers and lung adenocarcinoma [7, 23, 24, 27–29], but only expressed normally in mesothelial cells of the peritoneum, pericardium and pleura [27]. Like HE4, it has shown promise in the detection of early stage ovarian cancer, especially in combination with CA125 [1, 30, 31]. Improvements may be gained adding MSLN to a biomarker panel with CA125 and HE4 to detect early stage disease [15, 31] although contradictory results have been reported [32, 33]. Levels of detection of MSLN from serum and plasma for ovarian cancer were shown to be similar [34]. One issue with measuring MSLN in serum is that levels can be affected by conditions such as age, body mass index (BMI) and glomerular filtration rate [16]. Less expensive, facile screening can be achieved screening urine over serum or plasma. It is of interest, therefore, that MSLN was detected with more sensitivity in urine than serum for both early stage (42% vs. 12%, respectively) and late stage (75% and 48%, respectively) disease [35].

Although the literature is sparser than that for MSLN, a few studies have looked at MPF as a biomarker for mesothelioma [36], ovarian cancer [23] and pancreatic cancer [37]. As biomarkers in mesothelioma, MSLN and MPF have been shown to behave similarly [17–19].

Panels of biomarkers, able to cover the molecular heterogeneity of ovarian cancer [31, 38], or specific to high grade serous carcinoma [12], will be the most effective way to detect early disease for fewer fatalities. To date, no panel has been identified that can achieve the sensitivity (>75%) and specificity (>99.6%) needed to meet the accepted criteria of no more than ten surgeries for every case of early stage ovarian cancer identified. The most desirable biomarkers to add to panels will be those expressed early in disease, and not expressed in normal tissue.

One such biomarker is folate receptor alpha (FRA), a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored protein involved in folate transport into cells that is expressed in breast, lung, clear cell renal, ovarian and endometrial carcinomas, and non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma [39–58]. FRA is expressed in a high percentage of serous ovarian carcinomas in all stages and grades [44, 46, 55, 59, 60], and levels of circulating FRA have been shown to be comparable between early and late stage disease [54, 56]. Expression of FRA in normal tissues is restricted to the apical surfaces of some polarized epithelial cells [40].

In the present work, novel, sensitive electrochemiluminescent assays were developed for the soluble forms of FRA, MSLN and MPF and were evaluated in a large cohort of ovarian cancer patient samples. Further, the diagnostic utility of these markers was compared to CA125 and HE4 in a subset of serous ovarian cancer samples. Finally, a multi-marker logistic regression model was developed that demonstrates increased diagnostic performance relative to any single marker.

Materials and methods

Patient samples and controls

Samples were obtained from various commercial vendors with Institutional Review Board approvals and patient consent and were collected between 2009 and 2011. This study included serum samples from 258 ovarian cancer cases, of which 215 were serous and 47 were non-serous carcinoma (five unknown), and 60 age-matched control samples from women without disease. All non-serous ovarian cancer samples (endometrioid, mucinous, clear cell), were from women with stage I or II tumors.

In addition, serum, plasma and urine samples were collected from 57 women (37 with ovarian cancer and 20 without the disease as controls) to compare sample matrices. All serum, plasma and urine samples were collected by standard techniques and processed/frozen within 30 min of collection. All samples were stored at -80°C, and thawed and aliquotted prior to analysis. Patient demographics including date of diagnosis, histology, stage, and age (Table 1) were obtained from the suppliers.

Biomarker assays

Antibodies and antigens

The generation and characterization of monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) to FRA have been described previously [61]. MAbs MN and MB [62] against MSLN were purchased from Rockland Immunochemicals (Gilbertsville, PA). MAbs MPF25 and MPF49, specific for megakaryocyte potentiating factor (MPF) were obtained from Dr. Ira Pastan (Center for Cancer Research, NCI) and have been described previously [36]. All MAbs were murine IgG and purified by Protein A chromatography.

Purified, recombinant human FRA and human MSLN were the kind gift of Dr. Earl Albone (Morphotek Inc., Exton PA). MPF was prepared as a H6-construct and purified by metal-chelate chromatography. All antigens were demonstrated to be >98% pure by both SDS-PAGE and analytical SEC.

Novel electrochemiluminescence (ECL) assay

The FRA, MSLN and MPF assays all utilized ECL technology from MSD [63]. For the development of the FRA assay, 18 purified MAbs were screened pairwise and MAb pairs were selected from an unbiased screen using recombinant protein, normal pooled plasma and normal pooled urine. The final MAb pair was selected based on sensitivity, specificity, physical properties, and recognition of native protein. The selection of MAb pairs for MSLN (MN and MB) and MPF (MPF25 and MPF49) was determined based on literature. Detection MAbs were labeled with ruthenium (SULFO-TAGTM NHS-Ester, Meso Scale Discovery (MSD®), Rockville, MD) and label:protein was determined according the manufacturer’s instructions. The conjugation ratio was set to 20 labels per MAb for all assays.

Assay protocol

Samples (serum, plasma, urine), standards or controls were added to wells of a 96-well plate previously coated with capture antibody and incubated at RT for two-hours. The Ruthenium labeled detection MAbs were diluted in assay buffer, added to washed plates and incubated for an additional two hours at RT. Plates were washed, read buffer added and signals measured using an MSD DISCOVERY WORKBENCH®. Optimal sample dilutions were: FRA (80-fold dilution of urine and a 20-fold dilution of serum and plasma), MSLN (60-fold dilution of urine and an 80-fold dilution of serum and plasma) and MPF (4-fold dilution of urine and a 20-fold dilution of serum and plasma).

CA125 and HE4 measurements were performed by Myriad RBM (Austin, TX) on a Luminex 100 instrument on 176 serum samples from women with serous ovarian tumors.

Statistical analyses

Pearson’s correlation coefficient was performed to determine the correlation among the various biomarkers. Pairwise comparisons of biomarker levels between normal controls and stages and grades of ovarian cancer were made using the Mann–Whitney U test. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis was employed to determine the performance of these markers by stage and grade of disease. ROC Area Under the Curve (AUC) calculations were based on 95% confidence intervals. Logistic regression models were developed and used to assess the performance of a panel of biomarkers relative to CA125. All comparisons were two-sided and a P-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant except where otherwise stated. Statistical analyses were performed in MedCalc version 12.30 (MedCalc Corp.), SPSS version 19 (IBM), GraphPad Prism version 6.00 (GraphPad Software, Inc.) and Microsoft Excel version 2010.

Results

ECL assay reproducibility, sensitivity and reliability

The intraday reproducibility and sensitivity of the ECL assays for FRA, MSLN and MPF were assessed at levels between 0.01 and 5000 pg/mL (Figure 1). Mean intraday variability (CV) ranging from 2-16% for FRA, 3-7% for MSLN and 2-10% for MPF were observed and demonstrate good reproducibility for all three assays. All three assays also showed excellent sensitivity with lower limits of detection (LLOD) of 1.22, 0.29 and 3.35 pg/mL for FRA, MSLN and MPF, respectively. Representative calibrator curves are shown in Figure 1 and each assay demonstrates a wide dynamic range, potentially minimizing the need for re-assay of samples with high biomarker levels.

Assay range and sensitivity representative calibrator curves. A) FRA assay mean intraday variability (CV) ranged from 2-16% with a lower limit of detection (LLOD) of 1.22 pg/mL, B) MSLN assay mean CV ranged from 3-7% with an LLOD of 0.29 pg/mL and C) MPF assay mean CV ranged from 2-10% with an LLOD of 3.35 pg/mL.

Comparison of matrices: serum, plasma and urine

To assess the most appropriate matrix for determination of the various biomarker levels, matched serum/plasma pairs from 20 normal women and 37 women with ovarian cancer were measured for FRA, MSLN and MPF using the described ECL assays. As presented in Figure 2, a high degree of concordance was observed between serum and plasma for each of the three biomarkers, with Pearson’s correlation coefficients of r=0.96-0.99 and slopes of 0.87-0.97, indicating that either sample type is suitable for the determination of these markers and there appears not to be a preferential distribution between either matrix. Based on these data, and the relative availability of samples, all subsequent analyses were performed using serum samples.

Of interest, however, all three markers were also detectable in urine samples from the same 57 individuals noted above, indicating that urine could serve as a diagnostic matrix in ovarian cancer.

Diagnostic performance of FRA, MSLN and MPF in ovarian cancer cases of multiple histologies

Using the described ECL assays, the serum levels of FRA, MSLN and MPF were measured in samples from 258 ovarian cancers and 60 age-matched controls. Data for the ovarian cancer samples was analyzed by histotype, stage (AJCC) and grade of disease and is summarized in Table 2. Serum levels of all biomarkers differed significantly between ovarian cancer and control serum samples (Figure 3), with P values of <0.0001, <0.0001 and 0.0006 for FRA, MSLN and MPF, respectively. ROC curve analysis resulted in AUCs of 0.80 (p<0.0001) for FRA and MSLN (p<0.0001) and 0.641 (p=0.0007) for MPF (Figure 3) suggesting that FRA and MSLN have greater potential with respect to discrimination of individuals with ovarian cancer compared to normal individuals, independent of other clinical variables.

Box plots of serum levels of A) FRA, B) MSLN and C) MPF in healthy controls and ovarian cancer patients. Boxes indicate the 25th to 75th percentiles. The horizontal lines within the boxes are the median serum levels and the whiskers indicate the minimum and maximum values. P-values indicate statistical significance of differences between ovarian cancer cases and healthy controls. D) ROC (blue line, FRA; brown line, MSLN; orange line, MPF) curves showing the performance of serum biomarkers in discrimination of healthy controls and ovarian cancer patients.

Relative to histotype, FRA and MSLN both showed the highest levels and most significant discrimination with normals in the serous sub-type with p-values <0.0001. Both endometrioid and mucinous sub-types could also be discerned from normal by both FRA and MSLN although to lower significance than the serous sub-type (Figure 4). ROC curve analysis resulted in AUCs ranging from 0.72-0.82 (Figure 4). MPF on the other hand was significantly elevated only in the serous histotype with an AUC of 0.66 (Figure 4). Given the relatively low representation of endometrioid (22 samples) and mucinous (15 samples) in this cohort, the results of the analysis may be skewed and further studies in these histotypes are clearly warranted. Nonetheless, it is clear from this data that all three markers – FRA, MSLN and MPF – are elevated in serous ovarian cancer.

Box plots of serum levels of A) FRA, C) MSLN and E) MPF in healthy controls and ovarian cancer patients by tumor type: serous, endometrioid and mucinous. Boxes indicate the 25th to 75th percentiles. The horizontal lines within the boxes are the median serum levels and the whiskers indicate the minimum and maximum values. P-values indicate statistical significance of differences between each group and healthy controls. ROC curves showing the performance of B) FRA, D) MSLN and F) MPF serum biomarkers in discrimination of healthy controls and ovarian cancer patients by tumor type: serous (blue line); endometrioid (red line); mucinous (green line).

The serum levels of FRA, MSLN and MPF also differed by stage (Figure 5) and grade (Figure 6) of disease. All three markers showed a significant correlation to stage of disease and significantly higher levels in high grade tumors relative to low grade tumors. While levels of FRA and MSLN were also elevated in low grade tumors relative to normal, MPF was not able to distinguish low grade tumors from normal individuals. As shown in Figures 5 and 6, FRA and MSLN were more similar in diagnostic performance, as determined by ROC analyses, than was MPF.

Box plots of serum levels of A) FRA, C) MSLN and E) MPF in healthy controls and ovarian cancer patients by stage. Boxes indicate the 25th to 75th percentiles. The horizontal lines within the boxes are the median serum levels and the whiskers indicate the minimum and maximum values. P-values indicate statistical significance of differences between each group and healthy controls. ROC curves showing the performance of B) FRA, D) MSLN and F) MPF serum biomarkers in discrimination of healthy controls and ovarian cancer patients by stage (I, orange line; II, green line; III, red line; IV, blue line).

Box plots of serum levels of A) FRA, C) MSLN and E) MPF in healthy controls and ovarian cancer patients by grade. Boxes indicate the 25th to 75th percentiles. The horizontal lines within the boxes are the median serum levels and the whiskers indicate the minimum and maximum values. P-values indicate statistical significance of differences between each group and healthy controls. ROC curves showing the performance of B) FRA, D) MSLN and F) MPF serum biomarkers in discrimination of healthy controls and ovarian cancer patients by grade (low, blue line; high, red line).

Biomarker performance in serous ovarian cancer cases

Based on the data presented above and the preponderance of samples in our cohort from patients with serous ovarian cancer, a more detailed analysis of marker distributions and, importantly, comparisons to levels of CA125 and HE4 was performed on a subset of 176 serous ovarian samples.

Correlations of biomarkers

Pairwise comparisons between FRA, MSLN, MPF, CA125 and HE4 were made through use of Pearson’s correlation coefficient (Table 3). FRA was weakly correlated with CA125, HE4 and MPF, and moderately correlated with MSLN. Like FRA, CA125 was moderately correlated with MSLN and weakly correlated with the other markers. Given the literature that MSLN interacts with CA125 and may be involved in the metastatic process, the relatively low correlation (r=0.53) of these two markers in serum is somewhat surprising and may reflect different mechanisms by which these two proteins enter the circulation. Further, MPF and MSLN, molecular entities derived from the same gene product, were only correlated to r=0.66. This is most likely a reflection of the fact that MPF is a soluble, proteolytic cleavage product of the gene product whereas MSLN is GPI-anchored and requires additional processing to be released into the circulation. Interestingly, the strongest correlation of markers was for MPF and HE4 at r=0.83. The relatively low correlations between these 5 serum markers suggests involvement in different and varied biological processes in ovarian cancer and suggests their usefulness in a multi-marker panel for improved discriminatory ability over CA125 alone.

Diagnostic performance in serous histology

The serum levels of FRA, MSLN, CA125 and HE4 readily discriminated between serous ovarian cancer and control serum samples (Figure 7), with p-values of <0.0001 for FRA, MSLN and CA125, and 0.0002 and 0.0012 for HE4 and MPF, respectively. ROC analyses resulted in AUCs, in decreasing order, of 0.84 for CA125 (p<0.0001), 0.77 for FRA (p<0.0001), 0.76 for MSLN (p=<0.0001), 0.76 for HE4 (p=<0.0001), and 0.60 for MPF (p=0.0012) (Figure 7).

Box plots of serum levels of A) FRA, B) MSLN C) MPF D) CA125 and E) HE4 in healthy controls and serous ovarian cancer patients. Boxes indicate the 25th to 75th percentiles. The horizontal lines within the boxes are the median serum levels and the whiskers indicate the minimum and maximum values. P-values indicate statistical significance of differences between each group and healthy controls. F) ROC curves (FRA, blue line; MSLN, brown line; MPF, orange line; CA125, red line; HE4, green line) showing the performance of serum biomarkers in discrimination of healthy controls and serous ovarian cancer patients.

An assessment of each of the five biomarkers in the cohort of 176 serous ovarian cancer samples relative to stage of disease is presented in Figure 8. Each of the five markers showed clear trends of increasing levels with increasing stage of disease, although the level of significance of these changes varied widely. All markers were significantly increased in late stage disease, stages 3 and 4, relative to normal controls. CA125 and MSLN levels were shown to be significantly different from normal controls across all stages of disease.

Box plots of serum levels of A) FRA, C) MSLN, E) MPF G) CA125 and I) HE4 in healthy controls and serous ovarian cancer patients by stage. Boxes indicate the 25th to 75th percentiles. The horizontal lines within the boxes are the median serum levels and the whiskers indicate the minimum and maximum values. P-values indicate statistical significance of differences between each group and healthy controls. ROC curves showing the performance of B) FRA, D) MSLN, F) MPF, H) CA125 and J) HE4 serum biomarkers in discrimination of healthy controls and serous ovarian cancer patients by stage (I, orange line; II, green line; III, red line; IV, blue line).

Similarly, all five biomarkers were assessed relative to grade of disease (Figure 9). As can be seen, all markers were elevated and significantly different from normal controls in high grade disease. FRA, MSLN and CA125 were also significantly different in low grade disease. However, by ROC analysis, FRA was not able to distinguish low grade disease from normal controls (p=0.09) in this cohort. MSLN, MPF and HE4 were only able to distinguish high grade disease from normal controls, both by comparison of mean values and by ROC analysis (Figure 9).

Box plots of serum levels of A) FRA, C) MSLN and E) MPF G) CA125 and I) HE4in healthy controls and serous ovarian cancer patients by grade. Boxes indicate the 25th to 75th percentiles. The horizontal lines within the boxes are the median serum levels and the whiskers indicate the minimum and maximum values. P-values indicate statistical significance of differences between each group and healthy controls. ROC curves showing the performance of B) FRA, D) MSLN, F) MPF, H) CA125 and J) HE4 serum biomarkers in discrimination of healthy controls and serous ovarian cancer patients by grade (low, blue line; high, red line).

Multi-marker logistic regression modeling

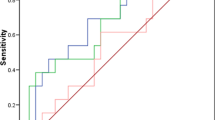

Given the diagnostic performance of the individual markers, and in particular the relatively weak correlation between markers, we applied logistic regression modeling in an attempt to define a combination of markers that would increase the diagnostic potential relative to the best single performing marker, CA125. In the resulting model, CA125 and MSLN were shown to increase the probability of a diagnosis of ovarian cancer as their values increased, whereas MPF showed the opposite effect. HE4 added slightly to the performance of the model, but it was not significant and therefore not included. The best model included CA125, FRA, MSLN and MPF and as can be seen in the ROC analysis presented in Figure 10, the ability of this four-marker panel to discriminate between ovarian cancer patients and healthy women was significantly improved (p=0.003) over that of CA125 alone: logistic regression (LR) AUC=0.91, p<0.0001; CA125 AUC=0.84, p<0.0001. The presented combination of markers may serve as a multi-marker panel to aid in the early diagnosis of EOC, particularly for the serous histology.

Performance of multi-marker panels for the discrimination of ovarian cancer patients (n=176) from healthy controls (n=20). ROC showing the performance of a four-biomarker panel, consisting of CA125, FRA, MSLN and MPF) in differentiating all ovarian cancer patients from healthy controls. The AUCs of the panel (AUC=0.91) was significantly improved over that of CA125 alone (AUC=0.84).

Discussion

CA125, first introduced in the mid-1980s, remains the gold standard with respect to detection and monitoring of ovarian cancer. In recent years other markers, in particular HE4 have gained acceptance, with somewhat limited utility [64–67], and some work has been reported on combining CA125 and HE4 to further increase the diagnostic application of these serum markers [2, 9, 11, 15]. Several other markers of ovarian cancer, including MSLN and, to a lesser extent, MPF have been described [1, 15, 23, 30–33]. However, there are no reports to our knowledge that have performed as comprehensive an analysis of all of these markers as presented here.

FRA has been the subject of intense research as a potential therapeutic target in the last several years primarily because of its highly restricted expression profile in normal tissues [40] and high levels expression in a number of cancers of epithelial origin, including serous ovarian cancer [39–52, 54–58, 68, 69]. Several late-stage clinical trials in ovarian cancer and non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma are presently on-going [68–70]. It is important, therefore, to develop robust assays for FRA both in tissue and in the circulation. With this in mind, the present work describes, for the first time, a specific and sensitive ECL-based assay using novel MAb reagents for the detection of FRA in serum, plasma and urine, allowing a comprehensive analysis of its diagnostic potential. Further, the potential clinical utility of serum MPF is not well documented. We therefore chose to develop a similar ECL-based assay for MPF for comparative studies not only to FRA, but to other more accepted markers of ovarian cancer – CA125, MSLN and HE4.

The described assays showed excellent limits of detection in the low pg/mL range and wide dynamic ranges up to at least 5000 pg/mL. From a practical point of view, such assays will require less in the way of repeat sample testing due to high marker levels. Importantly, FRA, MSLN and MPF were all shown to distribute equivalently between serum and plasma allowing flexibility in the choice of sample matrix. On the other hand, markers such as osteopontin are known to distribute more into the plasma fraction, restricting the sample type. FRA, MSLN and MPF were all shown to be detectable in urine samples from both healthy women and women with serous ovarian cancer. The clinical utility of MSLN measurement in urine for ovarian cancer has previously been described. In view of the ease of urine sample collection, the clinical utility of diagnostic assays assessing levels of FRA and MPF in urine is evident.

The data presented here demonstrates that for each of the markers analyzed – CA125, HE4, MSLN, MPF and FRA – there was a preferential expression in the serous histotype. Recent work from our laboratory using immunohistochemical techniques for the detection of FRA, have shown a similar preferential expression in serous carcinomas [59]. Taken together, these data support the current understanding of the origin of the various histotypes of ovarian cancer with the most common serous histotype deriving from tubal fimbriae [71]. Indeed, we recently demonstrated that FRA is highly expressed in tubal epithelium while normal ovary epithelium is devoid of FRA expression [59].

The analyzed markers showed low to moderate correlations with each other. Surprisingly, CA125 and MSLN were not highly correlated even though CA125 has been described to be the ligand for MSLN and to be involved in the metastatic process in ovarian cancer. More surprisingly, perhaps, is the moderate correlation between MSLN and MPF since these molecules should be present in a 1:1 molar ratio given the fact that they derive from the same RNA and that MPF is simply a proteolytic product of the initial gene product. However, since MSLN is a GPI-anchored protein whereas MPF is soluble, these findings, as with the correlations of the other described markers, most likely reflect a combination of the route by which the markers enter the circulation and, importantly, the clearance from the circulation. For example, while MSLN, MPF and FRA are detectable in urine, CA125 is not. Further, FRA has been shown to bind to megalin, both in the kidney and liver and, as such, is removed from circulation [72]. The glomerular filtration of at least some of these markers [32, 35, 73, 74], as well as the potential for other clearance mechanisms, has been described previously and may be a confounding factor in the measurement and application of these markers. Ultimately, this may explain the performance of CA125 as the single best marker for ovarian cancer.

However, as described herein, combining markers with CA125 does increase the diagnostic performance of the marker panel over CA125 alone, allowing for the development of a multi-marker panel that increases the sensitivity of detection of early stage disease while retaining specificity, the ultimate goal in ovarian cancer diagnosis.

Conclusions

CA125 remains the best single biomarker for diagnosis and monitoring of ovarian cancer. However, additional markers are sought for use independently or in combination with CA125 to improve the sensitivity for ovarian cancer detection whilst retaining specificity. The current study presents data on the utility of a novel marker, folate receptor alpha, FRA; with respect to discrimination between ovarian cancer, for example, the serous histotype, and normal controls. Further, data was presented for additional markers including MSLN and MPF and the use of these markers in a multi-marker panel that outperforms CA125 alone.

Development of additional markers for use either individually or in a panel for the diagnosis or detection of ovarian cancer, especially early stage disease, is critical. The novel ECL assays described herein provide a powerful tool for such development.

Abbreviations

- AJCC:

-

American joint committee on cancer

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CV:

-

Coefficient of variance

- ECL:

-

Electrochemiluminescence

- EOC:

-

Epithelial ovarian cancer

- FDA:

-

Food and drug administration

- FRA:

-

Folate receptor alpha

- GPI:

-

Glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- LLOD:

-

Lower limit of detection

- MAb:

-

Monoclonal antibody

- MPF:

-

Megakaryocyte potentiating factor

- MSLN:

-

Mesothelin

- ROC:

-

Receiver operator characteristic.

References

McIntosh MW, Drescher C, Karlan B, Scholler N, Urban N, Hellstrom KE: Combining CA 125 and SMR serum markers for diagnosis and early detection of ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2004, 95: 9–15.

Shah CA, Lowe KA, Paley P, Wallace E, Anderson GL, McIntosh MW: Influence of ovarian cancer risk status on the diagnostic performance of the serum biomarkers mesothelin, HE4, and CA125. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009, 18: 1365–1372.

Pauler DK, Menon U, McIntosh M, Symecko HL, Skates SJ, Jacobs IJ: Factors influencing serum CA125II levels in healthy postmenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2001, 10: 489–493.

Maggino T, Gadducci A, D'Addario V, Pecorelli S, Lissoni A, Stella M: Prospective multicenter study on CA 125 in postmenopausal pelvic masses. Gynecol Oncol 1994, 54: 117–123.

Markman M: The role of CA-125 in the management of ovarian cancer. Oncologist 1997, 2: 6–9.

Drapkin R, von Horsten HH, Lin Y, Mok SC, Crum CP, Welch WR: Human epididymis protein 4 (HE4) is a secreted glycoprotein that is overexpressed by serous and endometrioid ovarian carcinomas. Cancer Res 2005, 65: 2162–2169.

Galgano MT, Hampton GM, Frierson HF Jr: Comprehensive analysis of HE4 expression in normal and malignant human tissues. Mod Pathol 2006, 19: 847–853.

Hellstrom I, Raycraft J, Hayden-Ledbetter M, Ledbetter JA, Schummer M, McIntosh M: The HE4 (WFDC2) protein is a biomarker for ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res 2003, 63: 3695–3700.

Havrilesky LJ, Whitehead CM, Rubatt JM, Cheek RL, Groelke J, He Q: Evaluation of biomarker panels for early stage ovarian cancer detection and monitoring for disease recurrence. Gynecol Oncol 2008, 110: 374–382.

Moore RG, Brown AK, Miller MC, Badgwell D, Lu Z, Allard WJ: Utility of a novel serum tumor biomarker HE4 in patients with endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the uterus. Gynecol Oncol 2008, 110: 196–201.

Escudero JM, Auge JM, Filella X, Torne A, Pahisa J, Molina R: Comparison of serum human epididymis protein 4 with cancer antigen 125 as a tumor marker in patients with malignant and nonmalignant diseases. Clin Chem 2011, 57: 1534–1544.

Hellstrom I, Hellstrom KE: Two novel biomarkers, mesothelin and HE4, for diagnosis of ovarian carcinoma. Expert Opin Med Diagn 2011, 5: 227–240.

Lu KH, Patterson AP, Wang L, Marquez RT, Atkinson EN, Baggerly KA: Selection of potential markers for epithelial ovarian cancer with gene expression arrays and recursive descent partition analysis. Clin Cancer Res 2004, 10: 3291–3300.

Hellstrom I, Hellstrom KE: SMRP and HE4 as biomarkers for ovarian carcinoma when used alone and in combination with CA125 and/or each other. Adv Exp Med Biol 2008, 622: 15–21.

Moore RG, Brown AK, Miller MC, Skates S, Allard WJ, Verch T: The use of multiple novel tumor biomarkers for the detection of ovarian carcinoma in patients with a pelvic mass. Gynecol Oncol 2008, 108: 402–408.

Lowe KA, Shah C, Wallace E, Anderson G, Paley P, McIntosh M: Effects of personal characteristics on serum CA125, mesothelin, and HE4 levels in healthy postmenopausal women at high-risk for ovarian cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008, 17: 2480–2487.

Hollevoet K, Nackaerts K, Thimpont J, Germonpre P, Bosquee L, De VP: Diagnostic performance of soluble mesothelin and megakaryocyte potentiating factor in mesothelioma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010, 181: 620–625.

Creaney J, Francis RJ, Dick IM, Musk AW, Robinson BW, Byrne MJ: Serum soluble mesothelin concentrations in malignant pleural mesothelioma: relationship to tumor volume, clinical stage and changes in tumor burden. Clin Cancer Res 2011, 17: 1181–1189.

Wheatley-Price P, Yang B, Patsios D, Patel D, Ma C, Xu W: Soluble mesothelin-related Peptide and osteopontin as markers of response in malignant mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol 2010, 28: 3316–3322.

Yamaguchi N, Hattori K, Oh-Eda M, Kojima T, Imai N, Ochi N: A novel cytokine exhibiting megakaryocyte potentiating activity from a human pancreatic tumor cell line HPC-Y5. The Journal of Biological Chemisty 1994, 269: 805–808.

Kojima T, Oh-Eda M, Hattori K, Taniguchi Y, Tamura M, Ochi N: Molecular cloning and expression of megakaryocyte potentiating factor cDNA. J Biol Chem 1995, 270: 21984–21990.

Shiomi K, Miyamoto H, Segawa T, Hagiwara Y, Ota A, Maeda M: Novel ELISA system for detection of N-ERC/mesothelin in the sera of mesothelioma patients. Cancer Sci 2006, 97: 928–932.

Scholler N, Fu N, Ye Z, Goodman GE, Hellstrom KE, Hellstrom I: Soluble members of the mesothelin /megakaryocyte potentiating factor family are detectable in sera from patients with ovarian cancer. PNAS 1999, 96: 11531–11536.

Chang K, Pastan I: Molecular cloning of mesothelin, a differentiation antigen present on mesothelium, mesotheliomas, and ovarian cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996, 93: 136–140.

Rump A, Marikawa Y, Tanaka M, Minami S, Umesaki N, Takeuchi M: Binding of ovanian cancer antigen CA125/MUC16 to mesothelin mediates cell adhesion. The Journal of Biological Chemisty 2004, 279: 9190–9198.

Gubbels JA, Belisle J, Onda M, Rancourt C, Migneault M, Ho M: Mesothelin-MUC16 binding is a high affinity, N-glycan dependent interaction that facilitates peritoneal metastasis of ovarian tumors. Mol Cancer 2006, 5: 50.

Hassan R, Ho M: Mesothelin targeted cancer immunotherapy. Eur J Cancer 2008, 44: 46–53.

Ordonez NG: Value of mesothelin immunostaining in the diagnosis of mesothelioma. Mod Pathol 2003, 16: 192–197.

Robinson BW, Creaney J, Lake R, Nowak A, Musk AW, de Kierk N: Mesothelin-family proteins and diagnosis of mesothelioma. Lancet 2003, 362: 1612–1616.

Badgwell D, Bast RC Jr: Early detection of ovarian cancer. Dis Markers 2007, 23: 397–410.

Fritz-Rdzanek A, Grzybowski W, Beta J, Durczynski A, Jakimiuk A: HE4 protein and SMRP: Potential novel biomarkers in ovarian cancer detection. Oncol Lett 2012, 4: 385–389.

Hollevoet K, Speeckaert MM, Decavele AS, Vanholder R: van Meerbeeck JP. Delanghe JR: Mesothelin Levels in Urine are Affected by Glomerular Leakage and Tubular Reabsorption. Clin Lung Cancer; 2012.

Abdel-Azeez HA, Labib HA, Sharaf SM, Refai AN: HE4 and mesothelin: novel biomarkers of ovarian carcinoma in patients with pelvic masses. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2010, 11: 111–116.

Hellstrom I, Raycraft J, Kanan S, Sardesai NY, Verch T, Yang Y: Mesothelin variant 1 is released from tumor cells as a diagnostic marker. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006, 15: 1014–1020.

Badgwell D, Lu Z, Cole L, Fritsche H, Atkinson EN, Somers E: Urinary mesothelin provides greater sensitivity for early stage ovarian cancer than serum mesothelin, urinary hCG free beta subunit and urinary hCG beta core fragment. Gynecol Oncol 2007, 106: 490–497.

Onda M, Nagata S, Ho M, Bera TK, Hassan R, Alexander RH: Megakaryocyte potentiation factor cleaved from mesothelin precursor is a useful tumor marker in the serum of patients with mesothelioma. Clin Cancer Res 2006, 12: 4225–4231.

Inami K, Kajino K, Abe M, Hagiwara Y, Maeda M, Suyama M: Secretion of N-ERC/mesothelin and expression of C-ERC/mesothelin in human pancreatic ductal carcinoma. Oncol Rep 2008, 20: 1375–1380.

Das PM, Bast RC Jr: Early detection of ovarian cancer. Biomarker Medicine 2008, 2: 291–303.

O'Shannessy DJ, Somwar R, Maltzman J, Smale R, Fu Y-S: Folate receptor alpha (FRA) expression in breast cancer: identification of a new molecular subtype and association with triple negative disease. SpringerPlus 2012, 1: 22.

Weitman SD, Lark RH, Coney LR, Fort DW, Frasca V, Zurawski VR Jr: Distribution of the folate receptor GP38 in normal and malignant cell lines and tissues. Cancer Res 1992, 52: 3396–3401.

Weitman SD, Weinberg AG, Coney LR, Zurawski VR, Jennings DS, Kamen BA: Cellular localization of the folate receptor: potential role in drug toxicity and folate homeostasis. Cancer Res 1992, 52: 6708–6711.

Franklin WA, Waintrub M, Edwards D, Christensen K, Prendegrast P, Woods J: New anti-lung-cancer antibody cluster 12 reacts with human folate receptors present on adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer Suppl 1994, 8: 89–95.

Ross JF, Chaudhuri PK, Ratnam M: Differential regulation of folate receptor isoforms in normal and malignant tissues in vivo and in established cell lines. Physiologic and clinical implications. Cancer 1994, 73: 2432–2443.

Wu M, Gunning W, Ratnam M: Expression of folate receptor type alpha in relation to cell type, malignancy, and differentiation in ovary, uterus, and cervix. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1999, 8: 775–782.

Bueno R, Appasani K, Mercer H, Lester S, Sugarbaker D: The alpha folate receptor is highly activated in malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2001, 121: 225–233.

Parker N, Turk MJ, Westrick E, Lewis JD, Low PS, Leamon CP: Folate receptor expression in carcinomas and normal tissues determined by a quantitative radioligand binding assay. Anal Biochem 2005, 338: 284–293.

Shia J, Klimstra DS, Nitzkorski JR, Low PS, Gonen M, Landmann R: Immunohistochemical expression of folate receptor alpha in colorectal carcinoma: patterns and biological significance. Hum Pathol 2008, 39: 498–505.

Buist MR, Molthoff CF, Kenemans P, Meijer CJ: Distribution of OV-TL 3 and MOv18 in normal and malignant ovarian tissue. J Clin Pathol 1995, 48: 631–636.

Boerman OC, van Niekerk CC, Makkink K, Hanselaar TG, Kenemans P, Poels LG: Comparative immunohistochemical study of four monoclonal antibodies directed against ovarian carcinoma-associated antigens. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1991, 10: 15–25.

Iwakiri S, Sonobe M, Nagai S, Hirata T, Wada H, Miyahara R: Expression status of folate receptor alpha is significantly correlated with prognosis in non-small-cell lung cancers. Ann Surg Oncol 2008, 15: 889–899.

Markert S, Lassmann S, Gabriel B, Klar M, Werner M, Gitsch G: Alpha-folate receptor expression in epithelial ovarian carcinoma and non-neoplastic ovarian tissue. Anticancer Res 2008, 28: 3567–3572.

Veggian R, Fasolato S, Menard S, Minucci D, Pizzetti P, Regazzoni M: Immunohistochemical reactivity of a monoclonal antibody prepared against human ovarian carcinoma on normal and pathological female genital tissues. Tumori 1989, 75: 510–513.

Toffoli G, Cernigoi C, Russo A, Gallo A, Bagnoli M, Boiocchi M: Overexpression of folate binding protein in ovarian cancers. Int J Cancer 1997, 74: 193–198.

Toffoli G, Russo A, Gallo A, Cernigoi C, Miotti S, Sorio R: Expression of folate binding protein as a prognostic factor for response to platinum-containing chemotherapy and survival in human ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer 1998, 79: 121–126.

Kalli KR, Oberg AL, Keeney GL, Christianson TJ, Low PS, Knutson KL: Folate receptor alpha as a tumor target in epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2008, 108: 619–626.

Basal E, Eghbali-Fatourechi GZ, Kalli KR, Hartmann LC, Goodman KM, Goode EL: Functional folate receptor alpha is elevated in the blood of ovarian cancer patients. PLoS One 2009, 4: e6292.

O'Shannessy DJ, Yu G, Smale R, Fu YS, Singhal S, Thiel RP: Folate receptor alpha expression in lung cancer: diagnostic and prognostic significance. Oncotarget 2012, 3: 414–425.

Stein R, Goldenberg DM, Mattes MJ: Normal tissue reactivity of four anti-tumor monoclonal antibodies of clinical interest. Int J Cancer 1991, 47: 163–169.

O'Shannessy DJ, Somers EB, Smale R, Fu Y-S: Expression of Folate Receptor Alpha (FRA) in gynecologic malignancies and its relationship to the tumor type. Int J Gyne 2013. In press

Crane LM, Arts HJ, van OM, Low PS, van der Zee AG, van Dam GM: The effect of chemotherapy on expression of folate receptor-alpha in ovarian cancer. Cell Oncol (Dordr ) 2012, 35: 9–18.

O'Shannessy DJ, Somers EB, Albone E, Cheng X, Park YC, Tomkowicz BE: Characterization of the human folate receptor alpha via novel antibody-based probes. Oncotarget 2011, 2: 1227–1243.

Onda M, Willingham M, Nagata S, Bera TK, Beers R, Ho M: New monoclonal antibodies to mesothelin useful for immunohistochemistry, fluorescence-activated cell sorting, Western blotting, and ELISA. Clin Cancer Res 2005, 11: 5840–5846.

Debad J, Glezer EN, Leland JK, Sigal GB, Wohlstadter J: Clinical and Biological Applications of ECL. In Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence. Edited by: Bard AJ. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2004:359–396.

Schummer M, Drescher C, Forrest R, Gough S, Thorpe J, Hellstrom I: Evaluation of ovarian cancer remission markers HE4, MMP7 and Mesothelin by comparison to the established marker CA125. Gynecol Oncol 2012, 125: 65–69.

Bast RC Jr, Badgwell D, Lu Z, Marquez R, Rosen D, Liu J: New tumor markers: CA125 and beyond. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2005,15(Suppl 3):274–281.

Rosen DG, Wang L, Atkinson JN, Yu Y, Lu KH, Diamandis EP: Potential markers that complement expression of CA125 in epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2005, 99: 267–277.

Rein BJ, Gupta S, Dada R, Safi J, Michener C, Agarwal A: Potential markers for detection and monitoring of ovarian cancer. J Oncol 2011,201(1):475983.

Edelman MJ, Harb WA, Pal SE, Boccia RV, Kraut MJ, Bonomi P: Multicenter trial of EC145 in advanced, folate-receptor positive adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Thorac Oncol 2012, 7: 1618–1621.

Lorusso PM, Edelman MJ, Bever SL, Forman KM, Pilat M, Quinn MF: Phase I study of folate conjugate EC145 (Vintafolide) in patients with refractory solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 2012, 30: 4011–4016.

Konner JA, Bell-McGuinn KM, Sabbatini P, Hensley ML, Tew WP, Pandit-Taskar N: Farletuzumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against folate receptor alpha, in epithelial ovarian cancer: a phase I study. Clin Cancer Res 2010, 16: 5288–5295.

Kurman RJ, Shih IM: Molecular pathogenesis and extraovarian origin of epithelial ovarian cancer–shifting the paradigm. Hum Pathol 2011, 42: 918–931.

Birn H, Zhai X, Holm J, Hansen SI, Jacobsen C, Christensen E: Megalin binds and mediates cellular internalization of folate binding protein. FEBS J 2005, 272: 4423–4430.

Macuks R, Baidekalna I, Donina S: Urinary concentrations of human epidydimis secretory protein 4 (he4) in the diagnosis of ovarian cancer: a case- control study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2012, 13: 4695–4698.

Xiaofang Y, Yue Z, Xialian X, Zhibin Y: Serum tumour markers in patients with chronic kidney disease. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2007, 67: 661–667.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Jennifer Werkheiser for expert assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

The authors declare no conflicting interests in this study.

Authors’ contributions

DJO and ES conceived and designed the experiments. PO, RH and LM performed the experiments. RPT, LMP and DJO analyzed the data. LMP and DJO wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

O’Shannessy, D.J., Somers, E.B., Palmer, L.M. et al. Serum folate receptor alpha, mesothelin and megakaryocyte potentiating factor in ovarian cancer: association to disease stage and grade and comparison to CA125 and HE4. J Ovarian Res 6, 29 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-2215-6-29

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-2215-6-29