Abstract

Background

The precise mechanism of action for rituximab (R) is not fully elucidated. Besides antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), complements may also play an important role in the clinical response to rituximab-based therapy in diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL). The purpose of this study was to explore the relationship between C1qA [276] polymorphism and the clinical response to standard frontline treatment with R-CHOP in DLBCL patients.

Methods

Genotyping for C1qA [276A/G] was done in 164 patients with DLBCL. 129 patients treated with R-CHOP as frontline therapy (R ≥ 4 cycles) were assessable for the efficacy.

Results

Patients with homozygous A were found to have a higher overall response rate than those with heterozygous or homozygous G alleles (97.3% vs. 83.7%,P = 0.068). The complete response rate in patients with homozygous A was statistically higher than that in AG and GG allele carriers (89.2% vs. 51.1%,P = 0.0001). The overall survival of patients with homozygous A was longer than that of the G allele carriers (676 days vs. 497 days, P = 0.023). Multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that C1qA A/A allele was an independent favorable prognostic factor for DLBCL patients treated with R-CHOP as first-line therapy.

Conclusion

These results suggest that C1qA polymorphism may be a biomarker to predict response to R-CHOP as frontline therapy for DLBCL patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rituximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody targeted against the pan-B-cell marker CD20, has become a mainstay in the therapy of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) [1]. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common lymphoid neoplasm accounting for approximately 30% to 40% of all NHLs. The introduction of rituximab plus cyclophosphamide /doxorubicin /vincristine /prednisone (R-CHOP) chemotherapy has significantly improved the treatment outcome of DLBCL patients, especially non-germinal center B cell-like (non-GCB) subtypes [2–5]. However, not all patients with DLBCL showed good response to R-CHOP chemotherapy. Novel agents and prognostic factors are being explored to improve treatment outcome [6–10].

In addition to synergistic activity with CHOP [11], rituximab also appears to have an antitumor effect itself [12]. Evidences for multiple antitumor mechanisms of rituximab have been reported, including apoptosis [13, 14], complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) [15–17], and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) . It has been shown that the antitumor activity of rituximab was completely abolished in syngeneic C1q knockout mice and in a complement-depleted CVF mouse model [18, 19]. C1q is the trigger activation of the complement cascade in the presence of immune complexes, it’s formed by six trimers of A, B and C chains. The C1qA gene, located on chromosome 1p36.3-p34.1, contains several single nucleotide variations that are currently catalogued in the NCBI database. C1qA [276] (rs172378) is located at the beginning of the second exon. Racila E et al. reported that among 133 patients with follicular lymphoma treated with single-agent rituximab, polymorphisms in the C1qA [276] gene may have affected the clinical response and duration of response [20]. However, the impact of C1qA [276] polymorphism on the efficacy of rituximab in DLBCL patients remains unclear. In this study, we analyzed the relationships between C1qA polymorphism and the efficacy of primary R-CHOP therapy in 129 patients with DLBCL.

Materials and methods

Patient characteristics and treatment protocol

A total of 164 consented patients who received R-CHOP or R-CHOP-like chemotherapy between June 2007 and December 2010 as a frontline regimen were included in this retrospective study from Beijing Cancer Hospital. All patients had CD20+ DLBCL according to the World Health Organization classification as confirmed by our Department of Pathology. Peripheral blood samples from all lymphoma patients were obtained before the initiation of therapy. The clinical research protocol was approved by our Institutional Review Board (IRB).

R-CHOP chemotherapy was administered as follows: one course of chemotherapy consisted of an intravenous infusion of cyclophosphamide 750 mg/m2, adriamycin 50 mg/m2, vincristine 2 mg, and oral administration of 100 mg prednisone on days 1 to 5, which was repeated every 3 weeks. Rituximab 375 mg/m2 was infused over 4 to 6 hours on day 1 before CHOP or CHOP-like chemotherapy was started. Of the 129 patients, 31 patients received radiotherapy in involved-field. The response to R-CHOP therapy was evaluated after completion of 2 to 3 courses of therapy and 1 to 2 months after completion of all planned therapy, then every 3 months for the first year and every 6 months thereafter until progression.

DNA extraction and genotyping

Genomic DNA was isolated from whole blood with the Whole Blood Genome DNA isolation Kit (spin column) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Bioteke Corporation, China). DNA was diluted in water to a final stock concentration of 30 ng/ul, and 1ul was used in each PCR reaction. Determination of the C1qA [276A/G] genotype was achieved blindly on coded specimens by Sanger chain termination sequencing. Briefly, the genomic DNA region of interest was amplified using forward 5’TAAAGGAGACCAGGGGGAAC3’ and reverse 5’TTGAGGAGGAGACGATGGAC3’primers. A first denaturation step at 94°C for 3 min was followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 56°C for 30 s, extension at 72°C for 45 s, and a 10-min final extension step. The PCR products were visualized on a 2% agarose gel and then subjected to direct sequencing.

Definitions

Patients who had heterozygous (AG) or homozygous G (GG) genotype of C1qA [276] were designated as G carriers. Clinical responses were determined by physical examination and confirmed by computed tomography or ultrasound. The latter was only used for evaluating superficial lymph nodes. The responses were scored according to International Working Group criteria [21]. Overall survival (OS) was measured from day 1 of the first cycle of R-CHOP until death for any cause or the last follow-up available. The progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated from day 1 of the first cycle of R-CHOP to disease progression or death for any cause.

Statistical analysis

The clinical characteristics and response rate of the patients were compared using Chi-square, Fisher exact tests according to the C1qA SNP. Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the differences of PFS and OS. The Cox regression model was used to evaluate the prognostic factors. Differences between groups were regarded as significant with a p < 0.05. SPSS16.0 was used for all statistical analysis.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

The demographics and general characteristics of patients in this study are summarized in Table 1. Enrolled in the study were 81 female and 83 male patients. The median age at diagnosis was 53 years (range, 15–90 years). Eighty nine (54%) patients had stages 3 and 4 disease and 50 (30%) patients had intermediate-to-high or high International Prognostic Index (IPI) scores. Bone marrow was involved by lymphoma in 6 patients (4%) at the time of diagnosis. R-CHOP followed by involved-field radiation was given to 31 (19%) patients. One hundred and twenty-nine patients received R-CHOP as a frontline regimen and were therefore evaluable for this study. A median of 6 cycles of rituximab therapy was given (range, 4–14 cycles), and a median of 6 cycles of chemotherapy was given (range, 2–8 cycles).

C1qA 276 polymorphism

The frequency of the C1qA [276A] allele among all patients with lymphoma was 0.48, whereas the frequency of the C1qA [276G] allele was 0.52. Forty-four patients (27%) were homozygous A, whereas 50 patients (30%) were homozygous G, and 70 patients (43%) were heterozygous. The genotype distribution of DLBCL population enrolled in our study was in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium with regard to the C1qA [276] polymorphism examined (P = 0.06).

Patient characteristics according to C1qA allele status

No correlation was observed between patients’ disease features and the C1qA [276] genotype (Table 1). In the non-GCB subgroup, we observed the associations of the C1qA [276] genotype with abnormal β2-microglobulin level(defined as level > 3.0) (P = 0.012), but not B symptoms (P = 0.067). In the GCB subgroup, no association was found between the C1qA [276] genotype status and any of the factors (Table 2).

Responses to R-chemotherapy according to the C1qA [276] genotype

Of 129 patients evaluable for response to R-CHOP chemotherapy, the overall response rate (ORR) was 88% (113 of 129 patients), including complete response (CR) 62% (80 of 129 patients), and partial response (PR) rate 26% (33 of 129 patients). As shown in Table 3, homozygous A patients showed a trend of higher response when compared to the G allele carriers (P = 0.068). Higher CR rate was observed in patients with homozygous A when compared with G carriers (χ2 = 16.263, P = 0.0001). Among the responders, CR was seen in 33 of 37 (89.2%) homozygous A, 26 of 55 (47.3%) heterozygous, and 21 of 37 (56.8%) homozygous G patients (Table 3).

In subgroup analysis, a statistically higher CR rate was observed in the homozygous A patients compared with G carriers (81.8% vs 42.9%, χ2 = 16.263, P = 0.002). This was observed only in patients with non-GCB lymphoma.

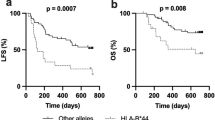

Survival analysis according to C1qA [276] genotype

After a median follow-up time of 524 days (range, 60–2073 days), 32 (25%) patients relapsed or progressed, and 18 (14%) died. Seven patients participated in a clinical trial evaluating everolimus (RAD001) and were censored for progression-free survival (PFS) analysis. The homozygous A patients had a median PFS of 623 days (range, 127–1177 days) versus 346 days (range, 42–1255 days) for the rest patients. This longer PFS however did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.063) (Figure 1). Survival data was available for 129 patients. The overall survival was 676 days (range, 143–1364 days) for homozygous A patients, and 497 days (range, 142–1350 days) for GG and AG carriers (P = 0.023, Figure 2). This difference was not seen when patients were subdivided into GCB- and non-GCB lymphoma groups (data not shown).

Multivariate analysis

A multivariate analysis was done to evaluate the following variables: stage (stages 1,2 vs. 3,4), IPI score (0–2 vs. 3–5), age (≤60 vs.>60 years), lactate dehydrogenase level (normal vs. abnormal), B symptoms (positive vs. negative), β2-microglobulin level (normal vs. abnormal), extranodal involvement (≤1 site vs. ≥2 sites), bulky mass (≥10 cm vs. <10 cm), and C1qA [276] (homozygous A vs. G carriers). This analysis confirmed that high IPI score (P = 0.033, HR 1.18, 95%CI 1.014-1.375) and abnormal β2-microglobulin level (P = 0.001, HR 2.599, 95%CI 1.639-4.121) were poor prognostic factors. When homozygous A was compared with the G carriers for overall survival in this analysis, the relative risk for OS was 0.595 (P = 0.018, 95%CI 0.386-0.915), favoring AA genotype.

Discussion

In this retrospective analysis, we found that homozygous A -allele carriers of the gene C1qA [276] had better overall response and higher complete response, and overall survival in DLBCL receiving R-CHOP. In subgroup analysis, higher CR was associated with homozygous A –allele in non-GCB lymphoma, but not GCB type. It is possible that this may be due to the small number of patients that preclude reliable analysis.

As mentioned earlier, a previous study of 133 patients with follicular lymphoma was done on the same C1qA[276][20]. The study showed that in follicular lymphoma patients treated with single agent rituximab, the duration of response and time to progression was significantly prolonged in patients with AA genotype. However, the response rate was similar in both AA and GG genotypes. In our study on DLBCL, the overall response and CR rates were both better in patients with AA genotype of C1qA[276]. Since the response was not based on PET/CT scan which is more sensitive than CT alone, the response rate could be different if PET/CT scan were used. PET/CT scan should be considered for response evaluation in future lymphoma studies.

It is unclear exactly how C1qA polymorphism affects the lymphoma responses to R-CHOP chemotherapy. The C1qA [276] G to A change is a synonymous polymorphism which does not introduce amino acid substitution. It was previously thought that such polymorphisms are “silent”, but now there is a growing body of evidence indicating that synonymous SNPs may alter the expression or function of a protein as well. For instance, synonymous SNPs within the DRD2 transcript can reduce the stability of the mRNA and thus the expression of the dopamine receptor [22]. Another mechanism that could lead to functional effects from a synonymous SNP is biased codon usage [23]. Vasostatin is an NH2-terminal fragment of human calreticulin, which is a natural receptor for C1q expressed by many cell types. Pike SE et al. found that vasostatin inhibit angiogenesis and tumor growth [24]. Interaction between calreticulin and C1q inhibits epithelial cell development and angiogenesis [25]. Therefore, C1q activity might affect tumor microenvironment or angiogenesis [20]. Taken all these together, it seems that C1q polymorphism may affect the expression level of C1q, which may account for the differences in clinical responses and treatment outcome in DLBCL. It will be interesting to study the C1q level in lymphoma patients prospectively and see whether it correlates with clinical outcome in lymphoma patients.

References

Plosker GL, Figgitt DP: Rituximab: a review of its use in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Drugs. 2003, 63: 803-843. 10.2165/00003495-200363080-00005.

Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, Herbrecht R, Tilly H: CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002, 346: 235-242. 10.1056/NEJMoa011795.

Feugier P, Van Hoof A, Sebban C, Solal-Celigny P, Bouabdallah R: Long-term results of the R-CHOP study in the treatment of elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a study by the Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. J Clin Oncol. 2005, 23: 4117-4126. 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.131.

Habermann TM, Weller EA, Morrison VA, Gascoyne RD, Cassileth PA: Rituximab-CHOP versus CHOP alone or with maintenance rituximab in older patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006, 24: 3121-3127. 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1003.

Pfreundschuh M, Trumper L, Osterborg A, Pettengell R, Trneny M: CHOP-like chemotherapy plus rituximab versus CHOP-like chemotherapy alone in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: a randomised controlled trial by the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol. 2006, 7: 379-391. 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70664-7.

Tan J, Cang S, Ma Y, Petrillo RL, Liu D: Novel histone deacetylase inhibitors in clinical trials as anti-cancer agents. J Hematol Oncol. 2010, 3: 5-10.1186/1756-8722-3-5.

Wang J, Ke XY: The four types of Tregs in malignant lymphomas. J Hematol Oncol. 2011, 4: 50-10.1186/1756-8722-4-50.

Wu ZL, Song YQ, Shi YF, Zhu J: High nuclear expression of STAT3 is associated with unfavorable prognosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Hematol Oncol. 2011, 4: 31-10.1186/1756-8722-4-31.

Yuan Y, Liao YM, Hsueh CT, Mirshahidi HR: Novel targeted therapeutics: inhibitors of MDM2, ALK and PARP. J Hematol Oncol. 2011, 4: 16-10.1186/1756-8722-4-16.

Elbaz H, Stueckle T, Tse W, Rojanasakul Y, Dinu C: Digitoxin and its analogs as novel cancer therapeutics. Experimental Hematology & Oncology. 2012, 1: 4-10.1186/2162-3619-1-4.

Mounier N, Briere J, Gisselbrecht C, Emile JF, Lederlin P: Rituximab plus CHOP (R-CHOP) overcomes bcl-2–associated resistance to chemotherapy in elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Blood. 2003, 101: 4279-4284. 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3442.

Ansell SM, Witzig TE, Kurtin PJ, Sloan JA, Jelinek DF: Phase 1 study of interleukin-12 in combination with rituximab in patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2002, 99: 67-74. 10.1182/blood.V99.1.67.

Byrd JC, Kitada S, Flinn IW, Aron JL, Pearson M: The mechanism of tumor cell clearance by rituximab in vivo in patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: evidence of caspase activation and apoptosis induction. Blood. 2002, 99: 1038-1043. 10.1182/blood.V99.3.1038.

Shan D, Ledbetter JA, Press OW: Signaling events involved in anti-CD20-induced apoptosis of malignant human B cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2000, 48: 673-683. 10.1007/s002620050016.

Golay J, Zaffaroni L, Vaccari T, Lazzari M, Borleri GM: Biologic response of B lymphoma cells to anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab in vitro: CD55 and CD59 regulate complement-mediated cell lysis. Blood. 2000, 95: 3900-3908.

Harjunpaa A, Junnikkala S, Meri S: Rituximab (anti-CD20) therapy of B-cell lymphomas: direct complement killing is superior to cellular effector mechanisms. Scand J Immunol. 2000, 51: 634-641. 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2000.00745.x.

Idusogie EE, Presta LG, Gazzano-Santoro H, Totpal K, Wong PY: Mapping of the C1q binding site on rituxan, a chimeric antibody with a human IgG1 Fc. J Immunol. 2000, 164: 4178-4184.

Cragg MS, Glennie MJ: Antibody specificity controls in vivo effector mechanisms of anti-CD20 reagents. Blood. 2004, 103: 2738-2743. 10.1182/blood-2003-06-2031.

Di Gaetano N, Cittera E, Nota R, Vecchi A, Grieco V: Complement activation determines the therapeutic activity of rituximab in vivo. J Immunol. 2003, 171: 1581-1587.

Racila E, Link BK, Weng WK, Witzig TE, Ansell S: A polymorphism in the complement component C1qA correlates with prolonged response following rituximab therapy of follicular lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008, 14: 6697-6703. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0745.

Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, Shipp MA, Fisher RI: Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999, 17: 1244-

Duan J, Wainwright MS, Comeron JM, Saitou N, Sanders AR: Synonymous mutations in the human dopamine receptor D2 (DRD2) affect mRNA stability and synthesis of the receptor. Hum Mol Genet. 2003, 12: 205-216. 10.1093/hmg/ddg055.

Carlini DB, Chen Y, Stephan W: The relationship between third-codon position nucleotide content, codon bias, mRNA secondary structure and gene expression in the drosophilid alcohol dehydrogenase genes Adh and Adhr. Genetics. 2001, 159: 623-633.

Pike SE, Yao L, Jones KD, Cherney B, Appella E: Vasostatin, a calreticulin fragment, inhibits angiogenesis and suppresses tumor growth. J Exp Med. 1998, 188: 2349-2356. 10.1084/jem.188.12.2349.

Stuart GR, Lynch NJ, Lu J, Geick A, Moffatt BE: Localisation of the C1q binding site within C1q receptor/calreticulin. FEBS Lett. 1996, 397: 245-249. 10.1016/S0014-5793(96)01156-8.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the grant of the National Science Foundation Committee of China (No.30973484).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interests.

Authors’ contributions

ZJ and SYQ designed the study and review the final manuscript. JX and DHR performed and evaluated the experiment. DN helped to performed the experiment. FZY helped to collect the specimens. JX collected and analyzed data. JX, SYQ and DHR wrote the manuscript. JX and DHR are joint first author, these authors contributed equally to the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Jin, X., Ding, H., Ding, N. et al. Homozygous A polymorphism of the complement C1qA 276 correlates with prolonged overall survival in patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. J Hematol Oncol 5, 51 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-8722-5-51

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-8722-5-51