Abstract

Background

The objectives of the present study are to investigate the efficacy and safety profile of gemcitabine-based combinations in the treatment of locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma (LA/MPC).

Methods

We performed a computerized search using combinations of the following keywords: "chemotherapy", "gemcitabine", "trial", and "pancreatic cancer".

Results

Thirty-five trials were included in the present analysis, with a total of 9,979 patients accrued. The analysis showed that the gemcitabine-based combination therapy was associated with significantly better overall survival (OS) (ORs, 1.15; p = 0.011), progression-free survival (PFS) (ORs, 1.27; p < 0.001), and overall response rate (ORR) (ORs, 1.58; p < 0.001) than gemcitabine monotherapy. Similar results were obtained when the gemcitabine-fluoropyrimidine combination was compared with gemcitabine, with the OS (ORs, 1.33; p = 0.007), PFS (ORs, 1.53; p < 0.001), and ORR (ORs 1.47, p = 0.03) being better in the case of the former. The OS (ORs, 1.33; p = 0.019), PFS (ORs, 1.38; p = 0.011), and one-year survival (ORs, 1.40; p = 0.04) achieved with the gemcitabine-oxaliplatin combination were significantly greater than those achieved with gemcitabine alone. However, no survival benefit (OS: ORs, 1.01, p = 0.93; PFS: ORs, 1.19, p = 0.17) was noted when the gemcitabine-cisplatin combination was compared to gemcitabine monotherapy. The combinations of gemcitabine and other cytotoxic agents also afforded disappointing results. Our analysis indicated that the ORR improved when patients were treated with the gemcitabine-camptothecin combination rather than gemcitabine alone (ORs, 2.03; p = 0.003); however, there were no differences in the OS (ORs, 1.03; p = 0.82) and PFS (ORs, 0.97; p = 0.78) in this case.

Conclusions

Gemcitabine in combination with capecitabine or oxaliplatin was associated with enhanced OS and ORR as compared with gemcitabine in monotherapy, which are likely to become the preferred standard first-line treatment of LA/MPC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is the fifth leading cause of death due to solid tumors in Western industrialized countries. Because pancreatic adenocarcinoma is often difficult to detect in early stages, most patients are diagnosed with advanced or metastatic disease at first presentation [1, 2]. The median survival of patients with locally advanced disease is 6 to 10 months, compared to 3 to 6 months for patients with metastatic disease [3].

Gemcitabine (Gemzar™; 2',2'-difluorodeoxycytidine) is a pyrimidine antimetabolite and a specific analogue of deoxycytidine. At present, gemcitabine monotherapy remains the standard care for patients with locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma (LA/MPC) [4]. However, patients who receive this therapy have a median overall survival (OS) of only 5.65 months [5]. In an effort to increase the objective response rate (RR) and survival of LA/MPC patients, many trials have been carried out in the last ten years to evaluate gemcitabine monotherapy or combination therapy regimens. Currently, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines indicate that gemcitabine combined with one other agent is the optimal treatment for LA/MPC patients with evidence of category 2B disease (recommendation based on lower-level evidence).

It is unclear whether this regimen is the ideal treatment for LA/MPC or whether it should be reevaluated. Therefore, we undertook a systematic review and quantitative meta-analysis to evaluate the available evidence from relevant randomized trials. This review will summarize the various trials of gemcitabine-based chemotherapy regimens in LA/MPC and discuss how these results should affect clinical practice.

Methods

Search strategy

We carried out a comprehensive search of the literature for randomized controlled trials in Pubmed using the terms "chemotherapy," "gemcitabine," "trials," and "pancreatic cancer" (no limitation for language). In addition to full publications, abstracts presented at the annual meetings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the European Cancer Conference (ECCO) were included.

Selection criteria

To be eligible for inclusion, trials were required to be prospective, properly randomized and well designed, which we defined as matched for age, stage and performance status (PS) or Karnofsky performance status (KPS). Patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease were included in the study, and histologic or cytologic confirmation of pancreatic adenocarcinoma was required.

If a trial included concomitant interventions such as radiotherapy or radioisotope treatment that differed systematically between the investigated arms, the trial was excluded. Whenever we encountered reports pertaining to overlapping patient populations, we included only the report with longest follow-up (having the largest number of events) in the analysis. Only randomized trials were included, and randomization must have started on or after Jan 1, 1965. The deadline for eligible trial publication was July 30, 2010.

Data collection

Two reviewers (Jing Hu and Gang Zhao) assessed the identified abstracts. Both reviewers independently selected trials for inclusion according to prior agreement regarding the study population and intervention. Lei Tang and Ying-Chun Xu also cross-checked all data collected against the original articles. If one of the reviewers determined that an abstract was eligible, the full text of article was retrieved and reviewed in detail by all reviewers.

For the 35 trials included in the meta-analysis, we gathered the authors' names, journal, year of publication, sample size (randomized and analyzed) per arm, performance status, regimens used, line of treatment, median age of patients and information pertaining to study design (whether the trial reported the mode of randomization, allocation concealment, description of withdrawals per arm and blinding).

Statistical analysis

The meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager Version 4.2 (Nordic Cochran Centre, Copenhagen) and Comprehensive Meta Analysis Version 2 (Biostat™, Englewood, NJ). Heterogeneity between the trials was assessed to determine which model should be used. To assess statistical heterogeneity between studies, the Cochran Q test was performed with a predefined significance threshold of 0.05. Odds ratios (ORs) were the principal measurements of effect and were presented with a 95% confidence interval (CI). P values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All reported p-values result from two-sided versions of the respective tests. The revision of funnel plots did not reveal any considerable publication bias.

The primary outcome measurements were overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS, time from randomization to progression or death), and secondary endpoints were overall response rate (ORR, number of partial and complete responses) and toxicity. Toxicities recorded by the original research group were recorded in our analysis, and the most frequent events were analyzed. In order to optimize our assessment of response, we used trials that included patients with measurable or assessable diseases and that were analyzed predominantly according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria. Toxicity profiles were reported according to the WHO criteria.

Results

Selection of the trials

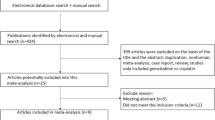

The literature search uncovered 762 articles. Primary screening led to the exclusion of 390 articles for the following reasons: reviews (218), other agents/regimens (43), radiotherapy/chemoradiation (99), letters/comments/editorials [26] or case reports [4]. The remaining 372 papers were retrieved for more detailed evaluation. Of these, 144 articles were excluded because of adjuvant chemotherapy, 44 for biliary tract cancer, 110 for phase I clinical trials, 38 for not-controlled design and 2 for repeated reports [6, 7]. In the end, a total of 35 randomized clinical trials [8–42] were eligible for inclusion in our analysis (Figure 1).

Characteristics of the trials included in the present analysis

Thirty-five trials were included in the present analysis, with a total of 9, 979 patients accrued. Characteristics of the eligible trials are listed in Table 1. Most of the trials (34/35, 97%) evaluated gemcitabine-based chemotherapy for first line or palliative chemotherapy in LA/MPC patients, whereas one trial (Palmer 2007) evaluated neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Twenty-three trials compared single-agent gemcitabine with gemcitabine combined with other cytotoxic agents, nine trials studied gemcitabine monotherapy with gemcitabine plus targeted therapy, and three trials evaluated triplet therapy for LA/MPC patients.

Among the thirty-five trials, the distribution of baseline patient characteristics was homogeneous. The percentage of patients with metastatic disease ranged from 50% to 91.1%, while the median age of patients varied from 57.8 to 66 (range: 23-96). The details of chemotherapeutic regimens per arm in each trial are shown in Table 2.

Trials comparing single-agent gemcitabine with gemcitabine combined with other cytotoxic agents

This analysis evaluated 23 trials (5,577 patients) comparing single-agent gemcitabine with gemcitabine-based combinations with other cytotoxic agents. For the primary endpoint of OS, the gemcitabine-based combination therapy was associated with significantly better outcome (ORs, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.03-1.28; p = 0.011) than gemcitabine in monotherapy (Figure 2A). The analysis of PFS also afforded favorable results for the combination arm, with the ORs being 1.27 (95% CI, 1.14-1.42; p < 0.001) (Figure 2B). A similar advantage for gemcitabine-based combinations was observed in terms of the ORR (ORs, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.31-1.91; p < 0.001), with no significant heterogeneity (p = 0.79).

Trials comparing gemcitabine alone with gemcitabine plus fluoropyrimidine

Six studies involving 1829 patients (Cunningham 2009, Bernhard 2008, Scheithauer 2003, Berlin 2004, Di Costanzo 2005, Riess 2005) compared single agent gemcitabine with gemcitabine plus fluoropyrimidine. Both oral capecitabine and infused 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) were evaluated in combination with gemcitabine in a variety of dosing schedules in these studies.

Our analysis showed a significant improvement in OS (ORs, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.08 to 1.64; p = 0.007) (Figure 3A), PFS (ORs, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.24 to 1.88; p = 0.000) and ORR (ORs, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.04 to 2.07; p = 0.03) when gemcitabine was combined with fluoropyrimidine. The ORs for 1-year survival in the gemcitabine plus fluoropyrimidine group as compared with the group that received gemcitabine alone was 1.08 (95% CI, 0.82 to 1.43; p = 0.58).

Comparison of gemcitabine plus fluoropyrimidine or platinum with gemcitabine alone on OS and PFS. A, gemcitabine/fluoropyrimidine versus gemcitabine alone on OS; B, gemcitabine/platinum versus gemcitabine alone on OS; C, gemcitabine/oxaliplatin versus gemcitabine alone on OS; D, gemcitabine/cisplatin versus gemcitabine alone on OS; E, gemcitabine/platinum versus gemcitabine alone on PFS; F, gemcitabine/oxaliplatin versus gemcitabine alone on PFS; G, gemcitabine/cisplatin versus gemcitabine alone on PFS.

Trials comparing gemcitabine alone with gemcitabine plus platinum

The combination of gemcitabine with platinum was evaluated in eleven trials involving 2,379 patients. Three trials used oxaliplatin (Louvet 2005, Poplin 2009, Yan 2007), and eight trials (Colucci 2010, Colucci 2002, Wang 2002, Heinemann 2006, Palmer 2007, Li 2004, Kulke 2009, Viret 2004) used cisplatin combined with gemcitabine. In these trials, the gemcitabine/platinum combinations prolonged OS in nine trials, whereas no survival benefit was seen in two trials (Colucci 2010, Wang X 2002).

Meta-analysis showed that the combination of gemcitabine with platinum resulted in a significant improvement in PFS (ORs, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.08 to 1.54; p = 0.005) (Figure 3E) as compared with gemcitabine in monotherapy, though no statistical significant difference in OS was observed (ORs, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.98 to 1.38; p = 0.08) (Figure 3B). When ORR was compared, the platinum combination arm showed significantly higher disease control, which was reflected by a pooled ORs of 1.48 (95% CI, 1.15 to 1.92; p = 0.002) in favor of the platinum combination (Figure 4C.).

Subgroup analysis comparing the gemcitabine/oxaliplatin group with the gemcitabine alone group gave an ORs of 1.33 (95% CI, 1.05 to 1.69) for OS and ORs of 1.38 (95% CI, 1.08 to 1.76) for PFS, which was statistically significant (p = 0.019, p = 0.011, seperately) in favor of gemcitabine/oxaliplatin combination (Figure 3C, F). However, the comparison of gemcitabine/cispiatin with gemcitabine alone showed that there was no survival benefit (OS: ORs, 1.01, p = 0.93; PFS: ORs, 1.19, p = 0.17) (Figure 3D, G). There was also a trend toward to increased ORR in the gemcitabine/cisplatin combination versus gemcitabine alone, with a pooled ORs of 1.38 (95% CI, 1.00 to 1.91), but the difference was not significant (p = 0.05). With regards to one-year survival, we did not find a difference between the gemcitabine/platinum group versus gemcitabine alone (OR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.92 to 1.44; p = 0.22) (Figure 4A), but there was a significant improvement in the gemcitabine/oxaliplatin group (OR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.93; p = 0.04) in the subgroup analysis (Figure 4B).

One trial (Palmer 2007) compared gemcitabine plus cisplatin with gemcitabine in the neoadjuvant setting. The study showed that the percentage of patients who underwent resection was 38% in gemcitabine arm versus 70% in the combination arm, with no increase in surgical complications. The 12-month survival percentages for the gemcitabine and combination groups were 42% and 62%, respectively. Combination therapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin was associated with a higher resection rate and an encouraging survival rate, suggesting that further study is warranted.

Trials comparing gemcitabine alone with gemcitabine plus camptothecin

Four randomized trials (n = 839) compared the combination of gemcitabine and topoisomerase I inhibitors (irinotecan or exatecan) with gemcitabine monotherapy. They included three studies (Kulke 2009, Stathopoulos 2006, Rocha Lima 2004) in which gemcitabine was combined with CPT-11 (irinotecan) and one study (Abou-Alfa 2006) in which gemcitabine was combined with exatecan. The analysis revealed a significant improvement in ORR for gemcitabine plus camptothecin therapy (ORs 2.03; 95% CI, 1.28 to 3.23; p = 0.003; heterogeneity, p = 0.14). However, the combination did not significantly improve OS or PFS. The pooled ORs for OS and PFS were 1.03 (95% CI, 0.81 to 1.32; p = 0.82) and 0.97 (95% CI, 0.76 to 1.23; p = 0.78), respectively (Figure 5).

Trials comparing gemcitabine monotherapy with gemcitabine plus other agents

Various other cytotoxic agents have been tested in combination with gemcitabine in LA/MPC patients, including pemetrexed (Alimta) and docetaxel. The analysis included two trials (n = 665), which indicated that the OS in the combination group was even lower than gemcitabine monotherapy (ORs, -0.10; 95% CI, -0.16 to -0.04; p = 0.002), although the ORR analysis showed therapeutic benefit of the combination (ORs, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.16 to 3.16; p = 0.01) (Figure 5B).

Oettle's trial, a randomized phase III study with 565 patients comparing the combination of gemcitabine and pemetrexed to gemcitabine alone, showed that OS was not improved in the combination arm (6.2 months) compared with the gemcitabine alone group (6.3 months) (p = 0.8477), although tumor response rate (14.8% versus 7.1%; p = 0.004) was significantly better in the combination arm.

Trials comparing gemcitabine monotherapy with gemcitabine plus targeted therapy

The role of new, targeted drugs in the treatment of advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma has been actively explored in the past few years. There are preliminary results and ongoing studies with EGFR inhibitors (erlotinib, cetuximab), farnesyltransferase inhibitors (tipifarnib), leukotriene B4 receptor antagonists (LY293111), antiangiogenic agents (axitinib, cilengitide), matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors (marimastat), vascular endothelial growth factor A inhibitors (bevacizumab), and histone deacetylase inhibitors (CI-994). However, most of these trials showed negative results.

In the present analysis, nine trials including 3, 342 patients evaluated gemcitabine combined with targeted therapy (Table 3). Although the results of the most recent trials (Philip 2010, Kindler 2010) are now available, which evaluated gemcitabine combined with C-225 or bevacizumab, so far Moore's trial is still the only study to demonstrate a significant improvement in survival in LA/MPC as a result of adding a targeted agent to gemcitabine. Therefore, the addition of other targeted agents is not recommended for the treatment of LA/MPC in the current clinical setting outside of a clinical trials.

Trials discussing gemcitabine doublets plus a third targeted reagent

Two trials (Cascino 2008, Vervenne 2008) including 691 patients evaluated a gemcitabine doublet with or without a third targeted reagent. In Cascino's multicenter randomized phase II trial, the addition of cetuximab to the gemcitabine/cisplatin combination did not increase PFS (hazard ratio 0.96, 95% CI, 0.60-1.52, p = 0.847) or OS (hazard ratio 0.91, 95% CI, 0.54-1.55, p = 0.739). In 2008, Vervenne compared the efficacy and safety of adding bevacizumab to erlotinib and gemcitabine in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. The results showed that addition of bevacizumab to erlotinib and gemcitabine did not significantly prolong OS, but there was a significant improvement in PFS (p = 0.0002). This combination requires further investigation in larger-scale clinical trials to assess efficacy and cost effectiveness.

Pooled analysis revealed slightly better disease control by adding a third reagent to the gemcitabine doublet, with an ORs of 1.62 (95% CI, 1.00 to 2.62), but this was not statistically significant (p = 0.05). Furthermore, the OS observed in the triplet group was disappointing (ORs, -0.79; 95% CI, -0.90 to -0.60; p < 0.00001).

Discussion

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is among the most challenging of solid malignancies to treat on account of its propensity for late presentation with inoperable disease, aggressive tumor biology and resistance to chemotherapy [43, 44]. Gemcitabine monotherapy has become a cornerstone of therapy for patients with LA/MPC since Burris et al reported their phase III trial results. Although it has shown clinical benefit, gemcitabine monotherapy has been associated with limited antitumor activity, with an ORR of 5% and median OS of 5.7 months [5]. In the past decade, many randomized controlled trials evaluated gemcitabine combined with various cytotoxic or targeted agents to try to improve outcomes for patients with LA/MPC. Some of these studies have reported improved median OS and one-year survival rates. However, the question of whether gemcitabine-based combinations are better than gemcitabine monotherapy is still unclear.

To compare the efficacy and tolerability of gemcitabine-based combinations in the treatment of LA/MPC with sufficient statistical power, we performed this meta-analysis to overcome the statistical limitations (for instance, low case load) of the individual trials and investigate treatment efficacy, safety profile and survival benefit of various therapeutic combinations.

The systematic review yielded five major findings. First, the analysis showed that gemcitabine-based combination was associated with significantly greater OS (ORs, 1.15; p = 0.011), PFS (ORs, 1.27; p < 0.001), and ORR (ORs, 1.58; p < 0.001) than gemcitabine monotherapy. The study reported by Heinemann revealed similar results [45]; their study considered 15 trials including 4465 patients for the analysis of OS. The analysis revealed a significant survival benefit for gemcitabine+X (X = cytotoxic agent) with a pooled ORs of 0.91 (p = 0.004) and indicated that patients with a good PS had a marked survival benefit when receiving combination chemotherapy (ORs, 0.76; p < 0.0001).

A similar advantage for gemcitabine combined with fluoropyrimidine was observed in terms of the OS (ORs, 1.33; p = 0.007), PFS (ORs, 1.53; p < 0.001), and ORR (ORs 1.47, p = 0.03) as compared to gemcitabine alone. Although the occurrence of hematological toxicities, including neutropenia (ORs, 1.60; p = 0.002) and thrombocytopenia (ORs, 1.52; p = 0.04), was higher in the combination group, the incidence of anemia (ORs, 0.97; p = 0.90) and non-hematological toxicities such as nausea/vomiting (ORs, 1.10; p = 0.60) were similar in both groups.

It remained to be determined whether the combination of gemcitabine with 5-FU or that with capecitabine was better. Bolus 5-FU and high-dose leucovorin have not shown meaningful therapeutic benefits in phase II studies [46]. However, researchers have speculated that continuous-infusion of 5-FU could improve its therapeutic efficacy. Capecitabine (N4-pentyloxycarbonyl-5'-deoxy-5-fluorocytidine) (Xeloda; F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland), an oral tumor-selective fluoropyrimidine, has been reported to be as efficacious as continuous-infusion 5-FU. Capecitabine appears to be a reasonable substitute for infused 5-FU/LV in combination regimens or as monotherapy, with the added advantage of reducing the inconvenience of long infusion times [47]. Cartwright [48] reported that capecitabine alone has an ORR of 7.3% and a disease control rate of 24% in previously untreated patients with LA/MPC. In Cunningham's report, gemcitabine/capecitabine significantly improved ORR (19.1% v 12.4%; p = 0.034) and PFS (hazard ratio, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.66 to 0.93; p = 0.004) and was associated with a trend toward improved OS (hazard ratio, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.72 to 1.02; p = 0.08) compared with gemcitabine alone. On the basis of these results, he recommended that gemcitabine/capecitabine should be considered one of the standard first-line options in LA/MPC.

In 1993, Wils [49] was the first to report that single-agent cisplatin has therapeutic activity in LA/MPC with an ORR of 21%. Soon afterwards, several phase II studies discussed the gemcitabine plus cisplatin combination in a variety of schedules. Adding cisplatin to gemcitabine appeared to be very active, with ORR ranging from 9% to 31% and median OS from 5.6 to 9.6 months in these phase II trials [50–52]. Furthermore, in the neoadjuvant setting, Palmer (2007) showed that combination therapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin was associated with a high resection rate and an encouraging survival rate.

However, the pooled analysis showed that the PFS and ORR achieved with the gemcitabine and platinum combination were significantly greater than those achieved with gemcitabine monotherapy; however, no statistically significant difference between the 2 treatment approaches were observed in the case of OS. This result was consistent with that obtained in a study conducted by Bria [4]. In Bria's meta-analysis, platinum combinations led to the greater absolute benefits in terms of PFS and ORR as compared with single-agent gemcitabine (10% and 6.5%, respectively), but did not result in an OS benefit. However, Heinemann [45] reported contrary results, with a ORs of 0.85 (p = 0.010) for platinum-gemcitabine combinations compared to gemcitabine alone. Heinemann's study included 15 trials with 4465 patients, whereas Bria's study included 20 trials with 6296 patients; our study included 35 trials with 9979 patients. The greater number of included trials and case load in our study may have contributed to the more favorable results obtained in our study.

Further, our subgroup analysis showed that the OS (p = 0.019), PFS (p = 0.011), and one-year survival (p = 0.04) in the gemcitabine-oxaliplatin group were significantly better than those in the gemcitabine monotherapy group. On the contrary, the comparison of gemcitabine-cisplatin with gemcitabine alone showed that there was no survival benefit (OS: p = 0.93; PFS: p = 0.17) with the former. Hence, we concluded that the combination of gemcitabine and oxaliplatin is superior to gemcitabine plus cisplatin and may be recommended as one of the standard first-line therapies for LA/MPC.

The third key finding was that the combination of gemcitabine plus other cytotoxic agents showed disappointing results. According to the literature, the combination of gemcitabine and irinotecan resulted in an objective response of 25% with a median OS ranging from 5.7 to 7 months (Rocha-Lima 2002, Stathopoulos 2004). Although our analysis found an enhanced ORR for gemcitabine plus camptothecin therapy (ORs, 2.03; p = 0.003), we did not find a significant difference in OS (ORs, 1.03; p = 0.82) or PFS (ORs, 0.97; p = 0.78) in the comparison. Other single agents including docetaxel and pemetrexed have also been tested in advanced pancreatic cancer. However, the analysis of two trials (n = 665) showed negative results. The OS in the combination group was even lower than that of patients receiving monotherapy (ORs, -0.10; p = 0.002), although the ORR analysis showed therapeutic benefit for this combination group (ORs, 1.91; p = 0.01).

Fourth, the identification of novel targets is still elusive for the treatment of LA/MPC. Since 2002, there has been a series of disappointing results. The only exception is erlotinib, which is the first and only targeted agent to demonstrate significantly improved survival in advanced pancreatic cancer when added to gemcitabine. Further research should be focused on new combinations or multi-target combined therapy, incorporating new, targeted therapies and identifying potential predictive factors of response.

The fifth finding concerned combining a gemcitabine doublet with or without a third targeted reagent. Our analysis revealed slightly better disease control by adding a third reagent to a gemcitabine doublet, with an ORs of 1.62 (95% CI, 1.00 to 2.62), but this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.05). The OS in the triplet group was also disappointing (ORs, -0.79; p < 0.00001). Vervenne's study showed that addition of bevacizumab to erlotinib and gemcitabine did not significantly prolong OS, but there was a significant improvement in PFS (p = 0.0002). This suggested that multi-target therapy may be a future direction for the treatment of advanced pancreatic cancer. This combination should be further evaluated in larger clinical trials to assess its efficacy and cost effectiveness.

The present meta-analysis was not based on individual patient data and was not subjected to an open external-evaluation procedure. Therefore, the analysis is limited in that the use of published data may have led to an overestimation of the treatment effects. Although the risk of publication bias exists in any meta-analysis, we believe that this did not greatly affect our results because many positive and negative trials were included in the study.

Moreover, some trials investigated gemcitabine-free combinations such as irinotecan/docetaxel or FOLFIRINOX for the treatment of LA/MPC. Among them, FOLFIRINOX (5-FU/leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin) is an interesting and promising combination. At the 2007 ASCO annual meeting, Ychou reported that the use of FOLFIRINOX as the first-line treatment for advanced pancreatic cancer afforded a response rate of greater than 30% with manageable toxicity in ECOG 0-1 patients [53]. In another study, Breysacher discussed the role of FOLFIRINOX as second-line therapy for metastatic pancreatic cancer [54]. No response was seen in 13 patients, and the one-year survival rate was 62%. However, a large-scale randomized clinical trial is required to evaluate the efficacy of FOLFIRINOX.

In the end, the goals of treatment for advanced pancreatic cancer should be to control tumor progression, alleviate disease-related symptoms and improve and maintain patients' quality of life (QOL). Reni [55] reported on the effects of a gemcitabine combination versus monotherapy on patient QOL. The study showed that the largest differences between arms favored the gemcitabine combination group. Clinically relevant improvement in QOL from baseline was observed more often after combination therapy than after gemcitabine, suggesting that the combination regimen did not impair QOL.

Conclusion

In general, the benefits of adding capecitabine or oxaliplatin to gemcitabine chemotherapy in LA/MPC are clear, with prolonged survival, improvement in disease control and improvement or stabilization of QOL as compared with gemcitabine monotherapy.

References

Evans DB, Abbruzzese JL, Willett CG: Cancer of the pancreas. Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. Edited by: VV D Jr, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA ets. 2001, Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 1126-1161. 6

Zhang XJ, Ye H, Zeng CW, He B, Zhang H, Chen YQ: Dysregulation of miR-15a and miR-214 in human pancreatic cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2010, 3: 46-10.1186/1756-8722-3-46.

Goulart BH, Clark JW, Lauwers GY, David R, Nina G, Alona M, Andrew Z: Long term survivors with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma treated with gemcitabine: a retrospective analysis. J Hematol Oncol. 2009, 2: 13-10.1186/1756-8722-2-13.

Bria E, Milella M, Gelibter A, Cuppone F, Pino MS, Ruggeri EM, Carlini P, Nisticò C, Terzoli E, Cognetti F, Giannarelli D: Gemcitabine-based combination for inoperable pancreatic cancer: have we made real progress?. Cancer. 2007, 110 (3): 525-533. 10.1002/cncr.22809.

Burris HA, Moore MJ, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML, Modiano MR, Cripps MC, Portenoy RK, Storniolo AM, Tarassoff P, Nelson R, Dorr FA, Stephens CD, Von Hoff DD: Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997, 15: 2403-2413.

Kulke MH, Niedzwiecki D, Tempero MA, Hollis DR, Mayer RJ: A randomized phase II study of gemcitabine/cisplatin, gemcitabine fixed dose rate infusion, gemcitabine/docetaxel, or gemcitabine/irinotecan in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer (CALGB 89904). J Clin Oncol. 2004, 22: 4011-

Herrmann R, Bodoky G, Ruhstaller T, Glimelius B, Bajetta E, Schüller J, Saletti P, Bauer J, Figer A, Pestalozzi B, Köhne CH, Mingrone W, Stemmer SM, Tàmas K, Kornek GV, Koeberle D, Cina S, Bernhard J, Dietrich D, Scheithauer W: Gemcitabine plus capecitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer: a randomized, multicenter, phase III trial of the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research and the Central European Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007, 25: 2212-221. 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.0886.

Gong JF, Zhang XD, Li J, Di LJ, Jin ML, Shen L: Efficacy of gemcitabine-based chemotherapy on advanced pancreatic cancer. Ai Zheng. 2007, 26: 890-894.

Reni M, Cordio S, Milandri C, Passoni P, Bonetto E, Oliani C, Luppi G, Nicoletti R, Galli L, Bordonaro R, Passardi A, Zerbi A, Balzano G, Aldrighetti L, Staudacher C, Villa E, Di Carlo V: Gemcitabine versus cisplatin, epirubicin, fluorouracil, and gemcitabine in advanced pancreatic cancer: a randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005, 6: 369-376. 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70175-3.

Cunningham D, Chau I, Stocken DD, Valle JW, Smith D, Steward W, Harper PG, Dunn J, Tudur-Smith C, West J, Falk S, Crellin A, Adab F, Thompson J, Leonard P, Ostrowski J, Eatock M, Scheithauer W, Herrmann R, Neoptolemos JP: Phase III randomized comparison of gemcitabine versus gemcitabine plus capecitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009, 27: 5513-5518. 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2446.

Bernhard J, Dietrich D, Scheithauer W, Gerber D, Bodoky G, Ruhstaller T, Glimelius B, Bajetta E, Schüller J, Saletti P, Bauer J, Figer A, Pestalozzi BC, Köhne CH, Mingrone W, Stemmer SM, Tàmas K, Kornek GV, Koeberle D, Herrmann R: Clinical benefit and quality of life in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer receiving gemcitabine plus capecitabine versus gemcitabine alone: a randomized multicenter phase III clinical trial--SAKK 44/00-CECOG/PAN.1.3.001. J Clin Oncol. 2008, 26: 3695-3701. 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6240.

Scheithauer W, Schüll B, Ulrich-Pur H, Schmid K, Raderer M, Haider K, Kwasny W, Depisch D, Schneeweiss B, Lang F, Kornek GV: Biweekly high-dose gemcitabine alone or in combination with capecitabine in patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a randomized phase II trial. Ann Oncol. 2003, 14: 97-104. 10.1093/annonc/mdg029.

Berlin JD, Catalano P, Thomas JP, Kugler JW, Haller DG, Benson AB: Phase III study of gemcitabine in combination with fluorouracil versus gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic carcinoma: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial E2297. J Clin Oncol. 2002, 20: 3270-3275. 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.149.

Di Costanzo F, Carlini P, Doni L, Massidda B, Mattioli R, Iop A, Barletta E, Moscetti L, Recchia F, Tralongo P, Gasperoni S: Gemcitabine with or without continuous infusion 5-FU in advanced pancreatic cancer: a randomised phase II trial of the Italian oncology group for clinical research (GOIRC). Br J Cancer. 2005, 93: 185-189. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602640.

Riess H, Helm A, Niedergethmann M, Schmidt-Wolf I, Moik M, Hammer C, Zippel K, Weigang-Köhler K, Stauch M, Oettle H: A randomised, prospective, multicenter, phase III trial of gemcitabine, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), folinic acid vs. gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005, 23: 4009-10.1200/JCO.2005.08.964.

Louvet C, Labianca R, Hammel P, Lledo G, Zampino MG, André T, Zaniboni A, Ducreux M, Aitini E, Taïeb J, Faroux R, Lepere C, de Gramont A, GERCOR and GISCAD: Gemcitabine in combination with oxaliplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: results of a GERCOR and GISCAD phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005, 23: 3509-3516. 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.023.

Poplin E, Feng Y, Berlin J, Rothenberg ML, Hochster H, Mitchell E, Alberts S, O'Dwyer P, Haller D, Catalano P, Cella D, Benson AB: Phase III, randomized study of gemcitabine and oxaliplatin versus gemcitabine (fixed-dose rate infusion) compared with gemcitabine (30-minute infusion) in patients with pancreatic carcinoma E6201: a trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2009, 27: 3778-3785. 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.9007.

Yan ZC, Hong J, Xie G: Observation of therapeutic efficacy of a biweekly regimen of Gemzar plus oxaliplatin for 30 cases with advanced pancreatic cancer. Chin J Clin Oncol. 2007, 34: 322-325.

Colucci G, Labianca R, Di Costanzo F, Gebbia V, Cartenì G, Massidda B, Dapretto E, Manzione L, Piazza E, Sannicolò M, Ciaparrone M, Cavanna L, Giuliani F, Maiello E, Testa A, Pederzoli P, Falconi M, Gallo C, Di Maio M, Perrone F, GOIM; GISCAD and GOIRC: Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin compared with single-agent gemcitabine as first-line treatment of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: the GIP-1 study. J Clin Oncol. 2010, 28: 1645-1651. 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4433.

Colucci G, Giuliani F, Gebbia V, Biglietto M, Rabitti P, Uomo G, Cigolari S, Testa A, Maiello E, Lopez M: Gemcitabine alone or with cisplatin for the treatment of patients with locally advanced and/or metastatic pancreatic carcinoma: a prospective, randomized phase III study of the Gruppo Oncologia dell'Italia Meridionale. Cancer. 2002, 94: 902-910. 10.1002/cncr.10323.

Wang X, Ni Q, Jin M, Li Z, Wu Y, Zhao Y, Feng F: Gemcitabine or gemcitabine plus cisplatin for in 42 patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2002, 24: 404-407.

Heinemann V, Quietzsch D, Gieseler F, Gonnermann M, Schönekäs H, Rost A, Neuhaus H, Haag C, Clemens M, Heinrich B, Vehling-Kaiser U, Fuchs M, Fleckenstein D, Gesierich W, Uthgenannt D, Einsele H, Holstege A, Hinke A, Schalhorn A, Wilkowski R: Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006, 24: 3946-3952. 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1490.

Palmer DH, Stocken DD, Hewitt H, Markham CE, Hassan AB, Johnson PJ, Buckels JA, Bramhall SR: A randomized phase 2 trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in resectable pancreatic cancer: gemcitabine alone versus gemcitabine combined with cisplatin. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007, 14: 2088-2096. 10.1245/s10434-007-9384-x.

Li CP, Chao Y: A prospective randomized trial of gemcitabine alone or gemcitabine combined with cisplatin in the treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004, 22: 140-

Kulke MH, Tempero MA, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis DR, Kindler HL, Cusnir M, Enzinger PC, Gorsch SM, Goldberg RM, Mayer RJ: Randomized phase II study of gemcitabine administered at a fixed dose rate or in combination with cisplatin, docetaxel, or irinotecan in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer: CALGB 89904. J Clin Oncol. 2009, 27: 5506-5512. 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.1309.

Viret F, Ychou M, Lepille D, Mineur L, Navarro F, Topart D, Fonck M, Goineau J, Madroszyk-Flandin A, Chouaki N: Gemcitabine in combination with cisplatin (GP) versus gemcitabine (G) alone in the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: final results of a multicenter randomized phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2004, 22: 4118-

Stathopoulos GP, Syrigos K, Aravantinos G, Polyzos A, Papakotoulas P, Fountzilas G, Potamianou A, Ziras N, Boukovinas J, Varthalitis J, Androulakis N, Kotsakis A, Samonis G, Georgoulias V: A multicenter phase III trial comparing irinotecan-gemcitabine (IG) with gemcitabine (G) monotherapy as first-line treatment in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006, 95: 587-592. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603301.

Rocha Lima CM, Green MR, Rotche R, Miller WH, Jeffrey GM, Cisar LA, Morganti A, Orlando N, Gruia G, Miller LL: Irinotecan plus gemcitabine results in no survival advantage compared with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer despite increased tumor response rate. J Clin Oncol. 2004, 22: 3776-3783. 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.082.

Abou-Alfa GK, Letourneau R, Harker G, Modiano M, Hurwitz H, Tchekmedyian NS, Feit K, Ackerman J, De Jager RL, Eckhardt SG, O'Reilly EM: Randomized phase III study of exatecan and gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in untreated advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006, 24: 4441-4447. 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0201.

Oettle H, Richards D, Ramanathan RK, van Laethem JL, Peeters M, Fuchs M, Zimmermann A, John W, Von Hoff D, Arning M, Kindler HL: A phase III trial of pemetrexed plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine in patients with unresectable or metastatic pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol. 2005, 16: 1639-1645. 10.1093/annonc/mdi309.

Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, Figer A, Hecht JR, Gallinger S, Au HJ, Murawa P, Walde D, Wolff RA, Campos D, Lim R, Ding K, Clark G, Voskoglou-Nomikos T, Ptasynski M, Parulekar W, National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group: Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007, 25: 1960-1966. 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9525.

Van Cutsem E, van de Velde H, Karasek P, Oettle H, Vervenne WL, Szawlowski A, Schoffski P, Post S, Verslype C, Neumann H, Safran H, Humblet Y, Perez Ruixo J, Ma Y, Von Hoff D: Phase III trial of gemcitabine plus tipifarnib compared with gemcitabine plus placebo in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004, 22: 1430-1438. 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.112.

Philip PA, Benedetti J, Corless CL, Wong R, O'Reilly EM, Flynn PJ, Rowland KM, Atkins JN, Mirtsching BC, Rivkin SE, Khorana AA, Goldman B, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Abbruzzese JL, Blanke CD: Phase III study comparing gemcitabine plus cetuximab versus gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Southwest Oncology Group-directed intergroup trial S0205. J Clin Oncol. 2010, 28: 3605-3610. 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.7550.

Saif MW, Oettle H, Vervenne WL, Thomas JP, Spitzer G, Visseren-Grul C, Enas N, Richards DA: Randomized double-blind phase II trial comparing gemcitabine plus LY293111 versus gemcitabine plus placebo in advanced adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Cancer J. 2009, 15: 339-343. 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181b36264.

Spano JP, Chodkiewicz C, Maurel J, Wong R, Wasan H, Barone C, Létourneau R, Bajetta E, Pithavala Y, Bycott P, Trask P, Liau K, Ricart AD, Kim S, Rixe O: Efficacy of gemcitabine plus axitinib compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: an open-label randomised phase II study. Lancet. 2008, 371: 2101-2108. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60661-3.

Bramhall SR, Schulz J, Nemunaitis J, Brown PD, Baillet M, Buckels JA: A double-blind placebo-controlled, randomised study comparing gemcitabine and marimastat with gemcitabine and placebo as first line therapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2002, 87: 161-167. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600446.

Kindler HL, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, Sutherland S, Schrag D, Hurwitz H, Innocenti F, Mulcahy MF, O'Reilly E, Wozniak TF, Picus J, Bhargava P, Mayer RJ, Schilsky RL, Goldberg RM: Gemcitabine plus bevacizumab compared with gemcitabine plus placebo in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: phase III trial of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 80303). J Clin Oncol. 2010, 28: 3617-3622. 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.1386.

Richards DA, Boehm KA, Waterhouse DM, Wagener DJ, Krishnamurthi SS, Rosemurgy A, Grove W, Macdonald K, Gulyas S, Clark M, Dasse KD: Gemcitabine plus CI-994 offers no advantage over gemcitabine alone in the treatment of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: results of a phase II randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. Ann Oncol. 2006, 17: 1096-1102. 10.1093/annonc/mdl081.

Friess H, Langrehr JM, Oettle H, Raedle J, Niedergethmann M, Dittrich C, Hossfeld DK, Stöger H, Neyns B, Herzog P, Piedbois P, Dobrowolski F, Scheithauer W, Hawkins R, Katz F, Balcke P, Vermorken J, van Belle S, Davidson N, Esteve AA, Castellano D, Kleeff J, Tempia-Caliera AA, Kovar A, Nippgen J: A randomized multi-center phase II trial of the angiogenesis inhibitor Cilengitide (EMD 121974) and gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced unresectable pancreatic cancer. BMC Cancer. 2006, 6: 285-10.1186/1471-2407-6-285.

Cascinu S, Berardi R, Labianca R, Siena S, Falcone A, Aitini E, Barni S, Di Costanzo F, Dapretto E, Tonini G, Pierantoni C, Artale S, Rota S, Floriani I, Scartozzi M, Zaniboni A, Italian Group for the Study of Digestive Tract Cancer (GISCAD): Cetuximab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin compared with gemcitabine and cisplatin alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a randomised, multicentre, phase II trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008, 9: 39-44. 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70383-2.

Vervenne W, Bennouna J, Humblet Y, Gill S, Moore MJ, Van Laethem J, Shang A, Cosaert J, Verslype C, Van Cutsem E: A randomized, double-blind, placebo (P) controlled, multicenter phase III trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of adding bevacizumab (B) to erlotinib (E) and gemcitabine (G) in patients (pts) with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2008 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings (Post-Meeting Edition) (May 20 Supplement). 2008, 26: 4507-

Boeck S, Hoehler T, Seipelt G, Mahlberg R, Wein A, Hochhaus A, Boeck HP, Schmid B, Kettner E, Stauch M, Lordick F, Ko Y, Geissler M, Schoppmeyer K, Kojouharoff G, Golf A, Neugebauer S, Heinemann V: Capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (CapOx) versus capecitabine plus gemcitabine (CapGem) versus gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin (mGemOx): final results of a multicenter randomized phase II trial in advanced pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol. 2008, 19: 340-347. 10.1093/annonc/mdm467.

Chua YJ, Cunningham D: Chemotherapy for advanced pancreatic cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006, 20: 327-348. 10.1016/j.bpg.2005.10.003.

Javle M, Hsueh CT: Recent advances in gastrointestinal oncology - updates and insights from the 2009 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 2010, 3: 11-

Heinemann V, Boeck S, Hinke A, Labianca R, Louvet C: Meta-analysis of randomized trials: evaluation of benefit from gemcitabine-based combination chemotherapy applied in advanced pancreatic cancer. BMC Cancer. 2008, 8: 82-10.1186/1471-2407-8-82.

DeCaprio JA, Mayer RJ, Gonin R, Arbuck SG: Fluorouracil and high-dose leucovorin in previously untreated patients with advanced adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: results of a phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 1991, 9: 2128-2133.

Ling W, Fan J, Ma Y, Wang H: Capecitabine-based chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2010,

Cartwright TH, Cohn A, Varkey JA, Chen YM, Szatrowski TP, Cox JV, Schulz JJ: Phase II study of oral capecitabine in patients with advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002, 20: 160-164. 10.1200/JCO.20.1.160.

Wils JA, Kok T, Wagener DJ, Selleslags J, Duez N: Activity of cisplatin in adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Eur J Cancer. 1993, 29A: 203-204. 10.1016/0959-8049(93)90175-F.

Heinemann V, Wilke H, Mergenthaler HG, Clemens M, König H, Illiger HJ, Arning M, Schalhorn A, Possinger K, Fink U: Gemcitabine and cisplatin in the treatment of advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol. 2000, 11: 1399-1403. 10.1023/A:1026595525977.

Philip PA, Zalupski MM, Vaitkevicius VK, Arlauskas P, Chaplen R, Heilbrun LK, Adsay V, Weaver D, Shields AF: Phase II study of gemcitabine and cisplatin in the treatment of patients with advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer. 2001, 92: 569-577. 10.1002/1097-0142(20010801)92:3<569::AID-CNCR1356>3.0.CO;2-D.

Cascinu S, Labianca R, Catalano V, Barni S, Ferraù F, Beretta GD, Frontini L, Foa P, Pancera G, Priolo D, Graziano F, Mare M, Catalano G: Weekly gemcitabine and cisplatin chemotherapy: a well-tolerated but ineffective chemotherapeutic regimen in advanced pancreatic cancer patients. A report from the Italian Group for the Study of Digestive Tract Cancer (GISCAD). Ann Oncol. 2003, 14: 205-208. 10.1093/annonc/mdg061.

Javle M, Hsueh CT: Updates in Gastrointestinal Oncology - insights from the 2008 44th annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Hematol Oncol. 2009, 23 (2): 9-10.1186/1756-8722-2-9.

Ychou M, Desseigne F, Guimbaud R, Ducreux M, Bouché O, Bécouarn Y, Adenis A, Montoto-Grillot C, Luporsi E, Conroy T: Randomized phase II trial comparing folfirinox (5FU/leucovorin [LV], irinotecan [I] and oxaliplatin [O]) vs gemcitabine (G) as first-line treatment for metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma (MPA). First results of the ACCORD 11 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007, 4516-, 20 Suppl, , ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings Part I. Vol 25, No. 18S

Breysacher G, Kaatz O, Lemarignier C, Chiappa P, Roncalez D, Denis B, de Colmar HC: Safety and clinical effectiveness of FOLFIRINOX in metastatic pancreas cancer (MPC) after first-line chemotherapy. ASCO Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium. 2010, Abstract No. 269-

Reni M, Bonetto E, Cordio S, Passoni P, Milandri C, Cereda S, Spreafico A, Galli L, Bordonaro R, Staudacher C, Di Carlo V, Johnson CD: Quality of life assessment in advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: results from a phase III randomized trial. Pancreatology. 2006, 6: 454-463. 10.1159/000094563.

Acknowledgements

Grant Support: Leading academic discipline project of Shanghai Municipal Education Committee, Project Number: J50208; Shanghai Municipal Natural Science Foundation, Project Number: 09ZR1417900.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

HJ, TL and XYC performed computerized search of trials, contacted experts and participated in the trials selection. MY and ZG participated in the trials selection and performed the statistical analysis. WHX conceived of the study and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Jing Hu, Gang Zhao contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, J., Zhao, G., Wang, HX. et al. A meta-analysis of gemcitabine containing chemotherapy for locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Hematol Oncol 4, 11 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-8722-4-11

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-8722-4-11