Abstract

Hyperekplexia is a rare neurological disorder characterized by neonatal hypertonia, exaggerated startle responses to unexpected stimuli and a variable incidence of apnoea, intellectual disability and delays in speech acquisition. The majority of motor defects are successfully treated by clonazepam. Hyperekplexia is caused by hereditary mutations that disrupt the functioning of inhibitory glycinergic synapses in neuromotor pathways of the spinal cord and brainstem. The human glycine receptor α1 and β subunits, which predominate at these synapses, are the major targets of mutations. International genetic screening programs, that together have analysed several hundred probands, have recently generated a clear picture of genotype-phenotype correlations and the prevalence of different categories of hyperekplexia mutations. Focusing largely on this new information, this review seeks to summarise the effects of mutations on glycine receptor structure and function and how these functional alterations lead to hyperekplexia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Hyperekplexia and glycine receptors

Hyperekplexia (OMIM #149400), or human startle disease, was first reported in 1958 by Kirstein and Silfverskiold[1]. They described a family in which four members suffered sudden falls precipitated by ‘emotional’ stimuli including surprise, fear or stress. In 1966, Suhren and colleagues reported similar symptoms in a larger pedigree that were shown to be inherited in an autosomal dominant manner and were treatable by barbiturates[2]. We now know that hyperekplexia is a rare neurological disorder characterized by 1) episodic and generalized stiffness after birth which gradually subsides during the first years of life, 2) an increased likelihood of apnoea attacks, delayed speech acquisition and/or intellectual disability, 3) excessive startle reflexes to unexpected stimuli, particularly auditory or tactile, that persist throughout life, and 4) a transient generalized stiffness after startle reflexes that can result in injurious falls[3–6]. The classic startle response is characterized by forceful closure of eyes, rising of bent arms over the head and flexion of the neck, trunk, elbows, hips and knees (Figure 1). Consciousness is fully retained during these episodes, thus distinguishing hyperekplexia from epileptic seizures. Clonazepam, a benzodiazepine that positively modulates inhibitory synaptic gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) type-A receptor chloride channels, is a highly effective treatment[3].

Schematic of a hyperekplexia patient illustrating the sequence of movements during a startle reflex. Numbers represent elapsed time in ms. Reproduced with permission from Elsevier[2].

Shiang and colleagues were first to show that hyperekplexia is caused by hereditary mutations in the GLRA1 gene that encodes the α1 subunit of the inhibitory human glycine receptor (hGlyR) chloride channel[7]. Although the GLRA1 gene represents the major gene of effect[8, 9], hyperekplexia can also be caused by mutations in the GLRB gene which encodes the hGlyR β subunit[10–15] or in the SLC6A5 gene which encodes the presynaptic glycine transporter type-2[16–19]. Mutations have also been identified in the genes encoding the hGlyR synaptic clustering proteins, gephyrin[20] and collybistin[21]. However, the phenotypes resulting from the later mutations are more complex than the classical phenotype described above. The common feature of all these proteins is that they are required for the normal functioning of inhibitory glycinergic synapses. As a large proportion of hyperekplexia cases have no genetic explanation[4], the analysis of other proteins involved in the development or function of glycinergic synapses could reveal further susceptibility genes. At this stage, however, the proteomics of glycinergic synapses is not well understood.

Inhibitory glycinergic synapses are located predominantly in the spinal cord and brainstem[22–24] and disruptions to their function increase the general level of excitability of motor neurons, thus accounting for neonatal hypertonia. Although patients seem to develop compensatory mechanisms to cope with this chronically enhanced excitability, they are not able to deal with the increased inhibitory demand required to dampen strong, unexpected excitatory commands[3].

Recently, thanks to large-scale systematic genetic screening programs, several hundred hyperekplexia probands have been examined and the results have generated a clear picture of the type and prevalence of mutations, their inheritance modes and the mechanisms by which they affect hGlyR structure and function[8, 9, 11, 12, 25]. The field may thus be considered to have reached a state of maturity. The clinical presentation and genotype-phenotype correlations in hyperekplexia have recently been published[4, 5, 26]. The aim of this review is to summarise the effects of mutations on hGlyR structure and function and how these functional alterations lead to hyperekplexia.

Molecular structure, stoichiometry and expression of GlyRs

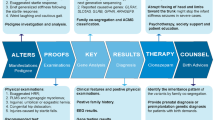

GlyRs belong to the Cys-loop family of pentameric ligand-gated ion channel (pLGIC) receptors. The X-ray molecular structures of several pLGIC receptors have been solved, including two bacterial homologues crystallized in the closed and open states, respectively[27–29], a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) from T. marmorata[30] and a glutamate-gated chloride channel receptor from C. elegans[31]. As this later receptor exhibits ~34% sequence homology with the α1 hGlyR subunit, it provides an excellent molecular structural template. As shown in Figure 2A, B GlyRs consist of five subunits arranged symmetrically in a ring around a central ion-conducting pore. Each subunit contains an extracellular domain (ECD), comprised mainly of a twisted β-sheet sandwich, harbouring the ligand binding site, and a transmembrane domain (TMD) comprising four α-helices, termed TM1 – TM4, with the five TM2 domains lining the axial channel pore. Both the extracellular β-sheets and transmembrane α-helices are connected by flexible loops. Glycine binds at the extracellular subunit interface and maximum gating efficacy is reached when three of the five binding sites are occupied[32]. Upon glycine binding, each ECD rotates relative to its TMD, ultimately inducing an outward tilt of the top of the TM2 domains which then opens the pore[33–35].

pLGIC structure and the locations of hGlyR hyperekplexia mutations. The top panel shows the pentameric structure of the C. elegans α glutamate-gated chloride channel receptor (PDB 3RIF[31]) viewed from within the membrane (A) and from the presynaptic terminal (B). One subunit is coloured light grey. Panels C-F show a single pLGIC subunit with the locations of dominant and recessive mutations in the α1 and β hGlyR subunits coloured in green (missense), red (nonsense) or black (deletions). TM2 is coloured dark grey.

In humans, four α subunits (α1 – α4) and a single β subunit have been described. The human α4 subunit is considered a pseudogene on the grounds that it incorporates a premature stop codon upstream of the final TM4 domain[36]. hGlyRs exist either as α homomers or as αβ heteromers in a stoichiometry of 2α:3β[37, 38] or 3α:2β[39]. As the β subunit mediates hGlyR attachment to the sub-synaptic clustering protein, gephyrin[40], it is presumed that only heteromeric αβ hGlyRs are present in synapses. Embryonic rats express predominantly α2 subunits, with the onset of β subunit expression coinciding with the first appearance of glycinergic synapses around the time of birth[41]. By three weeks postnatal in the rat spinal cord, most α2 subunits have been replaced by α1 subunits. In the adult spinal cord, α1 and β subunits are expressed in glycinergic synapses in motor reflex arcs, whereas α1, α3 and β subunits are all expressed in inhibitory synapses in pain sensory neurons in the superficial laminae of the dorsal horn[42]. In the cerebral cortex and hippocampus, GlyRs are extra-synaptic only and comprise predominantly α2 homomers or α2β heteromers[43–46]. This expression pattern implies that α1 and β subunits should be targets of hyperekplexia mutations whereas α2 and α3 subunits should not.

Hyperekplexia mutations in the hGlyR α1 subunit

Relationship between mutation type and inheritance mode

Most α1 hGlyR hyperekplexia mutations are either missense mutations whereby a single nucleotide change results in a codon change for a different amino acid, or nonsense mutations whereby a single nucleotide change leads to a premature stop codon (Table 1). Large deletions are also found, especially deletions of exons 1 – 7 in families of Turkish origin, suggesting that this is a population-specific risk-allele[9]. Hyperekplexia mutations can be inherited in both autosomal dominant or recessive modes with the majority of mutations being recessive (Table 1). Recessive mutations can be homozygous recessive, as first reported in 1994[47] or compound heterozygous, as first described in 1999[48]. Mutations can also be de novo meaning that neither parent possesses the mutation[49]. To date, there is no evidence for a correlation between clinical traits and inheritance mode of GLRA1 mutations[4].

GLRA1 nonsense and deletion/frameshift mutations, which lead to a loss of protein expression at the cell surface, are invariably autosomal recessive (Table 1). The reason for this is that the unaffected allele can generate sufficient quantities of protein to support normal glycinergic neurotransmission. In contrast, autosomal dominant mutations are missense mutations and invariably express strongly in cell surface-expressed hGlyRs, but diminish GlyR current-carrying capacity via spontaneous channel activity or via reductions in glycine sensitivity, zinc sensitivity, open probability and/or single channel conductance. Due to the efficient expression of these mutated subunits, their deleterious effects cannot be rescued by the unaffected allele. Recessive mutations are scattered throughout the α1 hGlyR subunit while dominant mutations are clustered in and around the pore-lining TM2 domain (Figure 2C, D).

Here, we describe the effects of those mutations (mainly autosomal dominant) that provide useful insights into the structure and function of hGlyRs and/or the pathophysiological mechanisms of hyperekplexia.

Spontaneous activation

So far, four GLRA1 mutations resulting in spontaneous channel activity have been identified: Y128C[9], Q226E, V280M and R414H[8]. All four mutations are autosomal dominant and the mutated subunits express strongly. Some possible mechanisms by which spontaneous hGlyR activation may give rise to hyperekplexia are considered below.

Q226E, located at the top of the TM1 domain (Figure 3A, B), also produces modest reductions in single channel conductance and cell surface expression efficiency that may contribute to the hyperekplexia phenotype[8]. Recent functional evidence suggests that Q226E induces receptor activation via an enhanced electrostatic attraction to R271 located at the top of the TM2 domain in the neighbouring subunit[25]. This attraction would tilt the top of the TM2 domain away from the pore axis, towards the TM1 domain, to constitutively open the channel. As detailed below, R271 is also an important hyperekplexia locus.

Proposed mechanism by which Q226E induces spontaneous activation. The TM1 and TM2 helices are coloured green and red, respectively, and are located in adjacent subunits. A. In the wild type (WT) α1 hGlyR, glycine induces activation by tilting the top of TM2 away from the pore axis towards TM1, where the open state is weakly stabilized by an H-bond between Q226 and R271. Hyperekplexia mutations at R271 are likely to disrupt this bond, thus destabilising the open state. B. In the Q226E mutant α1 hGlyR, a stable open state in the absence of glycine is induced via the formation of a strong electrostatic bond between Q226E and R271.

V280M, in the TM2-TM3 loop, exhibits a dramatically enhanced glycine sensitivity and spontaneous channel activity suggesting a drastic destabilization of the closed channel state[8]. We propose that the increased side chain volume of V280M exerts a steric repulsion against I225 at the top of the TM1 domain in the neighbouring subunit[25]. This would tilt the top of the TM3 domain radially outwards against the stationary TM1 domain and thus provide space for the TM2 domain to relax away from the pore axis to create an open channel.

Y128C is located in the inner β-sheet of the ECD. The mechanism by which it induces spontaneous activity is not yet resolved, but given its distance from the TMD, it seems likely that it causes non-specific structural alterations[9].

R414H, in the TM4 domain, results in a very low rate of spontaneous activity and has weak, if any, effects on glycine sensitivity, single channel conductance and expression efficiency[8]. It is thus unclear how this mutation causes hyperekplexia. As R414H has recently been identified as a rare single nucleotide polymorphism, it may not actually be responsible for hyperekplexia in the affected individual.

The high level of spontaneous activity in the Y128C, Q226E and V280M mutant hGlyRs directly contributes to the observed reduction in the glycine-induced current amplitude[8, 9]. The tonic chloride influx may also shift the chloride equilibrium potential to more positive values leading to a further reduction in the inhibitory efficacy of glycinergic neurotransmission or even a chronic depolarization that could lead to an increased action potential firing rate. In addition to directly activating neurons, tonic hGlyR activation could result in enhanced sodium and calcium influx rates. The effects of the mutations could thus be similar to those of nAChR slow-channel myasthenia mutations that result in ‘cationic overload’ of the postsynaptic region which destroys synaptic specializations and intracellular organelles[71]. As discussed below, a hyperekplexia mutation (L285R) in the hGlyR β subunit also causes spontaneous channel activity.

Impaired channel gating

R271Q and R271L, at the extracellular end of the TM2 domain, are the most frequently occurring and the most studied hyperekplexia mutations. They are both inherited in an autosomal dominant manner[7, 47, 65, 67, 72]. A rare autosomal dominant mutation at this site, R271P, is yet to be functionally characterized[64]. R271Q and R271L do not impair cell surface expression but dramatically reduce both the glycine sensitivity and the single channel conductance[73–77]. The decrease in single channel conductance most likely results from the elimination of the positive charge on R271. This would diminish the ability of the pore to concentrate chloride ions in its external vestibule, which would in turn reduce the chloride influx rate[25, 78]. Unfortunately, however, the effects of R271 mutations on glycine sensitivity do not have such a simple molecular explanation.

The TM2-TM3 loop located adjacent to R271 is an important structural element involved in transmitting glycine binding signals from the binding site to the activation gate[33–35]. Given that this is achieved via a highly organized network of energetic interactions between residues in the TM2-TM3 loop and the ECD, any alteration to loop structure would be expected to impair the efficient gating of the receptor, leading to reductions in glycine sensitivity and maximum open probability[79]. Evidence to date suggests that all hyperekplexia missense mutations in this loop, including R271Q/L/P, K276E/Q and Y279C/S, impair hGlyR function via a similar mechanism[74, 75, 79–81]. As illustrated in Figure 3, one specific effect of the R271 mutations is to disrupt a hydrogen bond with Q226 that is required to stabilise the open state[25]. Without this hydrogen bond, the open state would be destabilized, thereby reducing glycine sensitivity.

These and other mutations that impair channel gating cause hyperekplexia by reducing the rate of chloride influx through synaptic hGlyRs. Depending on the mutation, this may be achieved via a combination of a reduced maximum channel open probability, a reduced single channel conductance and/or a reduced the glycine sensitivity which would diminish the likelihood of the channels being effectively activated by synaptic glycine concentrations. The consequent reduction in glycinergic current magnitudes would disinhibit motor neurons thereby leading to enhanced firing activity and more potent muscle contractions. As noted above, hyperekplexia patients develop compensatory mechanisms to cope with the level of excitatory activity required for normal motor control[3]. One compensatory mechanism, identified in mouse models of hyperekplexia, is an enhancement of inhibitory GABAergic neutrotransmission[82], which may explain why clonazepam is an effective treatment. However, during startle episodes, the weakened inhibitory system is unable to dampen the excessive level of excitatory activity in motor neurons and the classic startle response results.

Although hyperekplexia patients with R271Q/L mutations are effectively treated with clonazepam[3, 4, 6], novel alternate therapeutic strategies are emerging. In one recent study, hGlyR function was restored by shifting the R271Q/L residue out of the allosteric signalling pathway via the mutation of surrounding residues[83]. This result raises the possibility of either designing or re-purposing drugs that bind in the alcohol/anaesthetic site near to R271 to achieve the same outcome[84]. In addition, the anaesthetic and GlyR positive allosteric modulator, propofol, preferentially enhances the potency of glycine in R271Q/L relative to α1 wild type hGlyRs[85, 86], and indeed, propofol successfully normalized hyperekplexia symptoms in a mouse carrying the R271Q mutation[86]. As propofol binds in the deep cleft near R271[87], it offers a starting point for identifying novel, more specific hyperekplexia treatments. Although the development of new drugs to treat specific hyperekplexia genotypes is unlikely to be economically viable, the re-purposing of existing clinically-approved drugs may be a realistic option.

The autosomal dominant mutation Q266H[61] in the TM2 domain reduces glycine sensitivity and single channel open times indicating that it also disrupts receptor gating efficacy[88]. Autosomal dominant hyperekplexia mutations to other pore-lining residues, V260M, T265I and S267N, similarly disrupt glycine efficacy[9, 62, 89]. Interestingly, the S267N mutation also abolishes hGlyR ethanol sensitivity[62], although the sensitivity of the patient to alcohol was not reported.

The autosomal dominant mutation R218Q in the ECD produces a dramatically reduced sensitivity to glycine, which is probably the primary reason for its hyperekplexia phenotype[49, 89]. Low concentrations of the competitive antagonist strychnine were similarly antagonized in wild type and R218Q-containing receptors suggesting that residue R218 plays an important role in channel gating, with only minor effects on glycine binding[89]. Recently, it was shown that the R218Q mutation disrupts a salt bridge between R218 and N148 that is crucial for efficient gating[90].

Increased desensitization rate

The autosomal dominant P250T mutation in the TM1-TM2 loop reduces glycine-activated current amplitudes and induces fast desensitization with a time constant near 120 ms[60, 91]. The reduced whole-cell current amplitude can be explained by a dramatic reduction in single channel conductance from around 80 to 1.3 pS, which no doubt accounts for much of the hyperekplexia phenotype[60]. In contrast, glycine sensitivity, affinity for strychnine and cell surface expression were similar to wild type receptors. Mutagenesis screening of neighbouring residues in the TM1-TM2 loop demonstrated that P250 is by far the most critical residue with respect to desensitization and glycine sensitivity[91]. Molecular dynamics simulations revealed an increased flexibility in P250T mutant hGlyRs which would destabilize the open state and explain the observed rapid desensitization[92]. The same publication also suggested that receptor activation and desensitization are structurally distinct processes as recently supported by a voltage-clamp fluorometry study[93]. As glycinergic synaptic currents exhibit decay time constants of 5 – 10 ms, it is unclear whether the enhanced desensitization rate induced by P250T is sufficient to limit chloride flux through the mutant channels and thereby contribute to the hyperekplexia phenotype.

The P230S hyperekplexia mutation in the TM1 domain also induces fast desensitization with a time constant near 1 s[8]. Additionally, this mutation reduces glycine sensitivity and maximal glycine-induced current amplitudes independent of β subunit co-expression. Genetic analysis of the patient with the P230S mutation suggested possible heterozygosity with R65W, although parental DNA was not available to confirm this. However, given the severity of the functional deficits resulting from the P230S mutation, we speculate it was most likely autosomal dominant. The R65W mutation eliminates cell surface expression and results in a recessive form of hyperekplexia[9].

Reduced cell surface expression

Many hyperekplexia mutations reduce cell surface expression, thereby reducing the maximal glycine-induced current amplitude. For the autosomal recessive mutations, S231R and I244N, both located in the TM1 domain, R252H in the TM2 domain and R392H in the TM4 domain, it was shown that treatment with the proteasome blocker lactacystin significantly increased the accumulation of mutated α1 subunits in intracellular membranes suggesting that the mutated subunits were recognized by the endoplasmatic reticulum control system and then degraded via the proteasome pathway[94]. Thus, the loss of glycinergic inhibition associated with many recessive hyperekplexia phenotypes may be due to the sequestration of mutated subunits within the endoplasmatic reticulum quality control system.

hGlyRs incorporating premature stop codons usually do not form functional receptors at the cell surface[9, 69, 95]. However, it has recently been shown that the autosomal recessive truncation mutation, E375X, which truncates the α1 hGlyR upstream of the TM4 domain, can be incorporated into functional receptors together with α1 wild type subunits[8]. hGlyRs containing the truncated subunit exhibited low cell surface expression and reduced glycine sensitivity. As this truncation occurs upstream of the naturally occurring premature stop codon in the human GLRA4 gene, it suggests that a review of the presumed pseudogene status of GLRA4[24, 36] and of other similarly classified pLGIC genes may be warranted.

Loss of zinc potentiation

Low concentrations of zinc (0.01 - 10 μM) have long been known to potentiate hGlyRs[96]. As zinc is concentrated in presynaptic terminals in the spinal cord and is released upon neuronal stimulation, its potentiating effect on glycinergic currents is likely to be physiologically relevant. Indeed, hyperekplexia symptoms were present in a genetically-modified mouse harbouring a mutant (D80A) α1 subunit that abolished zinc potentiation[97]. Recently, the GLRA1 V170S mutation was shown to produce an autosomal dominant form of hyperekplexia[56]. When these mutant receptors were recombinantly expressed in a mammalian cell line, V170S was found to have no effect on glycine sensitivity although it completely eliminated zinc potentiation[98]. This result implies that hyperekplexia can result from a reduction in glycinergic current magnitude due to the elimination of zinc potentiation.

Hyperekplexia mutations in the hGlyR β subunit

The GLRB gene has only recently been identified as a major gene of effect in hyperekplexia[10–12] although the first GLRB hyperekplexia mutation was identified in 2002[15]. To date, one autosomal dominant mutation, Y470C, is known[11], although the de novo L285R substitution is also likely autosomal dominant given the nature of its effect on receptor function (see below) and the fact that it was identified in a heterozygous proband[12]. The remaining mutations are autosomal recessive as either homozygous recessive or as compound heterozygous (Table 2). Around half of these mutations result in the excision of large amounts of β subunit protein which would most certainly eliminate functional expression. Most of the remaining mutations (P169L, M177R, G229D, △S262, W310C, R450X, Y470C) either reduce cell surface expression of functional heteromeric hGlyRs and/or cause modest reductions in glycine sensitivity[11, 12, 15], both of which are typical effects of recessive mutations. Although molecular modelling has provided insight into possible structural defects caused by these mutations[11, 12], experimental support for most of the model predictions is lacking to date.

The de novo mutation, L285R, provides an exception to the above pattern of effect on the grounds that it produces spontaneous channel activity when co-expressed with α1 wild type hGlyR subunits[11, 12], and because structural basis of its defect can be inferred with confidence. L285 is located at the 9′ position in the middle of the pore-lining TM2 domain[30]. It has long been recognized that 9′ leucines are very highly conserved among pLGIC receptors. These hydrophobic leucines protrude into the pore and their presence on each of the five subunits enables them to form a pentameric radially symmetrical arrangement of hydrophobic bonds that holds the channel closed. As many functional studies have demonstrated[99–102], substitution of one or more of these leucines with polar or charged residues disrupts some of the bonds, leading to a collapse of symmetry and the conversion of all TM2 domains to the open pore conformation. Thus, one mutated subunit per receptor would be sufficient to cause a significant, potentially damaging, chloride leak current.

Unlike GLRA1 mutations, GLRB mutations are strongly associated with delays in gross motor development and speech acquisition in humans[4]. This fact resembles the situation in zebrafish, where morpholino knockdown of the zebrafish orthologues of GLRA1 and GLRB results in distinct startle phenotypes[103]. The differential effect in mammals may be explained by the fact that β subunits are expressed at a much earlier developmental stage than α1 subunits, where they are involved in the formation of the first glycinergic synapses together with α2 subunits[23, 104].

Conclusions

GLRA1 and GLRB hyperekplexia mutations can be grouped into three main categories. The first includes those dominant mutations located in and around the TM2 domain that do not impair cell surface expression but disrupt hGlyR function by either inducing spontaneous channel activity or by reducing glycine sensitivity, chloride conductance and/or open probability. The second category includes those recessive missense mutations located throughout the receptor that result in a deficiency in cell surface targeting of hGlyRs. The final category includes recessive nonsense and deletion/frameshift mutations, the so called null genotypes, which preclude the formation of full length functional pentamers. The analysis of the molecular mechanisms of these mutations has provided unexpected insights into the structure and function of GlyRs and also into glycinergic signaling mechanisms in health and disease. By describing some of these molecular mechanisms, we hope that we have been able to provide explanations for the phenotypes of many gene-positive patients.

Abbreviations

- hGlyR:

-

Human glycine receptor

- nAChR:

-

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- pLGIC:

-

Pentameric ligand-gated ion channel

- TM:

-

Transmembrane.

References

Kirstein L, Silfverskiold BP: A family with emotionally precipitated drop seizures. Acta Psychiatr Neurol Scand. 1958, 33: 471-476. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1958.tb03533.x.

Suhren O, Bruyn GW, Tuynman JA: Hyperexplexia - a hereditary startle syndrome. J Neurol Sci. 1966, 3: 577-605. 10.1016/0022-510X(66)90047-5.

Bakker MJ, van Dijk JG, van den Maagdenberg AM, Tijssen MA: Startle syndromes. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5: 513-524. 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70470-7.

Thomas RH, Chung SK, Wood SE, Cushion TD, Drew CJ, Hammond CL, Vanbellinghen JF, Mullins JG, Rees MI: Genotype-phenotype correlations in hyperekplexia: apnoeas, learning difficulties and speech delay. Brain. 2013, 136: 3085-3095. 10.1093/brain/awt207.

Thomas RH, Harvey RJ, Rees MI: Hyperekplexia: stiffness, startle and syncope. J Pediatr Neurol. 2010, 8: 11-14.

Zhou L, Chillag KL, Nigro MA: Hyperekplexia: a treatable neurogenetic disease. Brain Dev. 2002, 24: 669-674. 10.1016/S0387-7604(02)00095-5.

Shiang R, Ryan SG, Zhu YZ, Hahn AF, O’Connell P, Wasmuth JJ: Mutations in the alpha 1 subunit of the inhibitory glycine receptor cause the dominant neurologic disorder, hyperekplexia. Nat Genet. 1993, 5: 351-358. 10.1038/ng1293-351.

Bode A, Wood SE, Mullins JG, Keramidas A, Cushion TD, Thomas RH, Pickrell WO, Drew CJ, Masri A, Jones EA, Vassallo G, Born AP, Alehan F, Aharoni S, Bannasch G, Bartsch M, Kara B, Krause A, Karam EG, Matta S, Jain V, Mandel H, Freilinger M, Graham GE, Hobson E, Chatfield S, Vincent-Delorme C, Rahme JE, Afawi Z, Berkovic SF, Howell OW, Vanbellinghen JF, Rees MI, Chung SK, Lynch JW: New hyperekplexia mutations provide insight into glycine receptor assembly, trafficking, and activation mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2013, 288: 33745-33759. 10.1074/jbc.M113.509240.

Chung SK, Vanbellinghen JF, Mullins JG, Robinson A, Hantke J, Hammond CL, Gilbert DF, Freilinger M, Ryan M, Kruer MC, Masri A, Gurses C, Ferrie C, Harvey K, Shiang R, Christodoulou J, Andermann F, Andermann E, Thomas RH, Harvey RJ, Lynch JW, Rees MI: Pathophysiological mechanisms of dominant and recessive GLRA1 mutations in hyperekplexia. J Neurosci. 2010, 30: 9612-9620. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1763-10.2010.

Al-Owain M, Colak D, Al-Bakheet A, Al-Hashmi N, Shuaib T, Al-Hemidan A, Aldhalaan H, Rahbeeni Z, Al-Sayed M, Al-Younes B, Ozand PT, Kaya N: Novel mutation in GLRB in a large family with hereditary hyperekplexia. Clin Genet. 2012, 81: 479-484. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01661.x.

Chung SK, Bode A, Cushion TD, Thomas RH, Hunt C, Wood SE, Pickrell WO, Drew CJ, Yamashita S, Shiang R, Leiz S, Longardt AC, Raile V, Weschke B, Puri RD, Verma IC, Harvey RJ, Ratnasinghe DD, Parker M, Rittey C, Masri A, Lingappa L, Howell OW, Vanbellinghen JF, Mullins JG, Lynch JW, Rees MI: GLRB is the third major gene of effect in hyperekplexia. Hum Mol Genet. 2013, 22: 927-940. 10.1093/hmg/dds498.

James VM, Bode A, Chung SK, Gill JL, Nielsen M, Cowan FM, Vujic M, Thomas RH, Rees MI, Harvey K, Keramidas A, Topf M, Ginjaar I, Lynch JW, Harvey RJ: Novel missense mutations in the glycine receptor beta subunit gene (GLRB) in startle disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2013, 52: 137-149.

Lee CG, Kwon MJ, Yu HJ, Nam SH, Lee J, Ki CS, Lee M: Clinical features and genetic analysis of children with hyperekplexia in Korea. J Child Neurol. 2013, 28: 90-94. 10.1177/0883073812441058.

Mine J, Taketani T, Otsubo S, Kishi K, Yamaguchi S: A 14-year-old girl with hyperekplexia having GLRB mutations. Brain Dev. 2013, 35: 660-663. 10.1016/j.braindev.2012.10.013.

Rees MI, Lewis TM, Kwok JB, Mortier GR, Govaert P, Snell RG, Schofield PR, Owen MJ: Hyperekplexia associated with compound heterozygote mutations in the beta-subunit of the human inhibitory glycine receptor (GLRB). Hum Mol Genet. 2002, 11: 853-860. 10.1093/hmg/11.7.853.

Carta E, Chung SK, James VM, Robinson A, Gill JL, Remy N, Vanbellinghen JF, Drew CJ, Cagdas S, Cameron D, Cowan FM, Del Toro M, Graham GE, Manzur AY, Masri A, Rivera S, Scalais E, Shiang R, Sinclair K, Stuart CA, Tijssen MA, Wise G, Zuberi SM, Harvey K, Pearce BR, Topf M, Thomas RH, Supplisson S, Rees MI, Harvey RJ: Mutations in the GlyT2 gene (SLC6A5) are a second major cause of startle disease. J Biol Chem. 2012, 287: 28975-28985. 10.1074/jbc.M112.372094.

Eulenburg V, Becker K, Gomeza J, Schmitt B, Becker CM, Betz H: Mutations within the human GLYT2 (SLC6A5) gene associated with hyperekplexia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006, 348: 400-405. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.07.080.

Gimenez C, Perez-Siles G, Martinez-Villarreal J, Arribas-Gonzalez E, Jimenez E, Nunez E, de Juan-Sanz J, Fernandez-Sanchez E, Garcia-Tardon N, Ibanez I, Romanelli V, Nevado J, James VM, Topf M, Chung SK, Thomas RH, Desviat LR, Aragon C, Zafra F, Rees MI, Lapunzina P, Harvey RJ, Lopez-Corcuera B: A novel dominant hyperekplexia mutation Y705C alters trafficking and biochemical properties of the presynaptic glycine transporter GlyT2. J Biol Chem. 2012, 287: 28986-29002. 10.1074/jbc.M111.319244.

Rees MI, Harvey K, Pearce BR, Chung SK, Duguid IC, Thomas P, Beatty S, Graham GE, Armstrong L, Shiang R, Abbott KJ, Zuberi SM, Stephenson JB, Owen MJ, Tijssen MA, van den Maagdenberg AM, Smart TG, Supplisson S, Harvey RJ: Mutations in the gene encoding GlyT2 (SLC6A5) define a presynaptic component of human startle disease. Nat Genet. 2006, 38: 801-806. 10.1038/ng1814.

Rees MI, Harvey K, Ward H, White JH, Evans L, Duguid IC, Hsu CC, Coleman SL, Miller J, Baer K, Waldvogel HJ, Gibbon F, Smart TG, Owen MJ, Harvey RJ, Snell RG: Isoform heterogeneity of the human gephyrin gene (GPHN), binding domains to the glycine receptor, and mutation analysis in hyperekplexia. J Biol Chem. 2003, 278: 24688-24696. 10.1074/jbc.M301070200.

Harvey K, Duguid IC, Alldred MJ, Beatty SE, Ward H, Keep NH, Lingenfelter SE, Pearce BR, Lundgren J, Owen MJ, Smart TG, Luscher B, Rees MI, Harvey RJ: The GDP-GTP exchange factor collybistin: an essential determinant of neuronal gephyrin clustering. J Neurosci. 2004, 24: 5816-5826. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1184-04.2004.

Chalphin AV, Saha MS: The specification of glycinergic neurons and the role of glycinergic transmission in development. Front Mol Neurosci. 2010, 3: 11-

Legendre P: The glycinergic inhibitory synapse. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001, 58: 760-793. 10.1007/PL00000899.

Lynch JW: Native glycine receptor subtypes and their physiological roles. Neuropharmacology. 2009, 56: 303-309. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.034.

Bode A, Lynch JW: Analysis of hyperekplexia mutations identifies transmembrane domain rearrangements that mediate glycine receptor activation. J Biol Chem. 2013, 288: 33760-33771. 10.1074/jbc.M113.513804.

Davies JS, Chung SK, Thomas RH, Robinson A, Hammond CL, Mullins JG, Carta E, Pearce BR, Harvey K, Harvey RJ, Rees MI: The glycinergic system in human startle disease: a genetic screening approach. Front Mol Neurosci. 2010, 3: 8-

Bocquet N, Nury H, Baaden M, Le Poupon C, Changeux JP, Delarue M, Corringer PJ: X-ray structure of a pentameric ligand-gated ion channel in an apparently open conformation. Nature. 2009, 457: 111-114. 10.1038/nature07462.

Hilf RJ, Dutzler R: X-ray structure of a prokaryotic pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. Nature. 2008, 452: 375-379. 10.1038/nature06717.

Hilf RJ, Dutzler R: Structure of a potentially open state of a proton-activated pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. Nature. 2009, 457: 115-118. 10.1038/nature07461.

Unwin N: Refined structure of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at 4A resolution. J Mol Biol. 2005, 346: 967-989. 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.031.

Hibbs RE, Gouaux E: Principles of activation and permeation in an anion-selective Cys-loop receptor. Nature. 2011, 474: 54-60. 10.1038/nature10139.

Beato M, Groot-Kormelink PJ, Colquhoun D, Sivilotti LG: Openings of the rat recombinant alpha 1 homomeric glycine receptor as a function of the number of agonist molecules bound. J Gen Physiol. 2002, 119: 443-466. 10.1085/jgp.20028530.

Calimet N, Simoes M, Changeux JP, Karplus M, Taly A, Cecchini M: A gating mechanism of pentameric ligand-gated ion channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013, 110: E3987-E3996. 10.1073/pnas.1313785110.

Corringer PJ, Baaden M, Bocquet N, Delarue M, Dufresne V, Nury H, Prevost M, Van Renterghem C: Atomic structure and dynamics of pentameric ligand-gated ion channels: new insight from bacterial homologues. J Physiol. 2010, 588: 565-572. 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.183160.

Miller PS, Smart TG: Binding, activation and modulation of Cys-loop receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010, 31: 161-174. 10.1016/j.tips.2009.12.005.

Simon J, Wakimoto H, Fujita N, Lalande M, Barnard EA: Analysis of the set of GABA (A) receptor genes in the human genome. J Biol Chem. 2004, 279: 41422-41435. 10.1074/jbc.M401354200.

Grudzinska J, Schemm R, Haeger S, Nicke A, Schmalzing G, Betz H, Laube B: The beta subunit determines the ligand binding properties of synaptic glycine receptors. Neuron. 2005, 45: 727-739. 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.028.

Yang Z, Taran E, Webb TI, Lynch JW: Stoichiometry and subunit arrangement of alpha1beta glycine receptors as determined by atomic force microscopy. Biochemistry. 2012, 51: 5229-5231. 10.1021/bi300063m.

Durisic N, Godin AG, Wever CM, Heyes CD, Lakadamyali M, Dent JA: Stoichiometry of the human glycine receptor revealed by direct subunit counting. J Neurosci. 2012, 32: 12915-12920. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2050-12.2012.

Meyer G, Kirsch J, Betz H, Langosch D: Identification of a gephyrin binding motif on the glycine receptor beta subunit. Neuron. 1995, 15: 563-572. 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90145-0.

Watanabe E, Akagi H: Distribution patterns of mRNAs encoding glycine receptor channels in the developing rat spinal cord. Neurosci Res. 1995, 23: 377-382. 10.1016/0168-0102(95)00972-V.

Harvey RJ, Depner UB, Wassle H, Ahmadi S, Heindl C, Reinold H, Smart TG, Harvey K, Schutz B, Abo-Salem OM, Zimmer A, Poisbeau P, Welzl H, Wolfer DP, Betz H, Zeilhofer HU, Muller U: GlyR alpha3: an essential target for spinal PGE2-mediated inflammatory pain sensitization. Science. 2004, 304: 884-887. 10.1126/science.1094925.

Avila A, Vidal PM, Dear TN, Harvey RJ, Rigo JM, Nguyen L: Glycine receptor alpha2 subunit activation promotes cortical interneuron migration. Cell Rep. 2013, 4: 738-750. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.07.016.

Jonsson S, Morud J, Pickering C, Adermark L, Ericson M, Soderpalm B: Changes in glycine receptor subunit expression in forebrain regions of the Wistar rat over development. Brain Res. 2012, 1446: 12-21.

Thio LL, Shanmugam A, Isenberg K, Yamada K: Benzodiazepines block alpha2-containing inhibitory glycine receptors in embryonic mouse hippocampal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2003, 90: 89-99. 10.1152/jn.00612.2002.

Young-Pearse TL, Ivic L, Kriegstein AR, Cepko CL: Characterization of mice with targeted deletion of glycine receptor alpha 2. Mol Cell Biol. 2006, 26: 5728-5734. 10.1128/MCB.00237-06.

Rees MI, Andrew M, Jawad S, Owen MJ: Evidence for recessive as well as dominant forms of startle disease (hyperekplexia) caused by mutations in the alpha 1 subunit of the inhibitory glycine receptor. Hum Mol Genet. 1994, 3: 2175-2179. 10.1093/hmg/3.12.2175.

Vergouwe MN, Tijssen MA, Peters AC, Wielaard R, Frants RR: Hyperekplexia phenotype due to compound heterozygosity for GLRA1 gene mutations. Ann Neurol. 1999, 46: 634-638. 10.1002/1531-8249(199910)46:4<634::AID-ANA12>3.0.CO;2-9.

del Giudice EM, Coppola G, Bellini G, Cirillo G, Scuccimarra G, Pascotto A: A mutation (V260M) in the middle of the M2 pore-lining domain of the glycine receptor causes hereditary hyperekplexia. Eur J Hum Genet. 2001, 9: 873-876. 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200729.

Brune W, Weber RG, Saul B, von Knebel Doeberitz M, Grond-Ginsbach C, Kellerman K, Meinck HM, Becker CM: A GLRA1 null mutation in recessive hyperekplexia challenges the functional role of glycine receptors. Am J Hum Genet. 1996, 58: 989-997.

Tsai CH, Chang FC, Su YC, Tsai FJ, Lu MK, Lee CC, Kuo CC, Yang YW, Lu CS: Two novel mutations of the glycine receptor gene in a Taiwanese hyperekplexia family. Neurology. 2004, 63: 893-896. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000138566.65519.67.

Rees MI, Lewis TM, Vafa B, Ferrie C, Corry P, Muntoni F, Jungbluth H, Stephenson JB, Kerr M, Snell RG, Schofield PR, Owen MJ: Compound heterozygosity and nonsense mutations in the alpha (1)-subunit of the inhibitory glycine receptor in hyperekplexia. Hum Genet. 2001, 109: 267-270. 10.1007/s004390100569.

Coto E, Armenta D, Espinosa R, Argente J, Castro MG, Alvarez V: Recessive hyperekplexia due to a new mutation (R100H) in the GLRA1 gene. Mov Disord. 2005, 20: 1626-1629. 10.1002/mds.20637.

Zoons E, Ginjaar IB, Bouma PA, Carpay JA, Tijssen MA: A new hyperekplexia family with a recessive frameshift mutation in the GLRA1 gene. Mov Disord. 2012, 27: 795-796. 10.1002/mds.24917.

Chan KK, Cherk SW, Lee HH, Poon WT, Chan AY: Hyperekplexia: a Chinese adolescent with 2 novel mutations of the GLRA1 gene. J Child Neurol. 2012, 29: 111-113.

Al-Futaisi AM, Al-Kindi MN, Al-Mawali AM, Koul RL, Al-Adawi S, Al-Yahyaee SA: Novel mutation of GLRA1 in Omani families with hyperekplexia and mild mental retardation. Pediatr Neurol. 2012, 46: 89-93. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2011.11.008.

Forsyth RJ, Gika AD, Ginjaar I, Tijssen MA: A novel GLRA1 mutation in a recessive hyperekplexia pedigree. Mov Disord. 2007, 22: 1643-1645. 10.1002/mds.21574.

Humeny A, Bonk T, Becker K, Jafari-Boroujerdi M, Stephani U, Reuter K, Becker CM: A novel recessive hyperekplexia allele GLRA1 (S231R): genotyping by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and functional characterisation as a determinant of cellular glycine receptor trafficking. Eur J Hum Genet. 2002, 10: 188-196. 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200779.

Gilbert SL, Ozdag F, Ulas UH, Dobyns WB, Lahn BT: Hereditary hyperekplexia caused by novel mutations of GLRA1 in Turkish families. Mol Diagn. 2004, 8: 151-155.

Saul B, Kuner T, Sobetzko D, Brune W, Hanefeld F, Meinck HM, Becker CM: Novel GLRA1 missense mutation (P250T) in dominant hyperekplexia defines an intracellular determinant of glycine receptor channel gating. J Neurosci. 1999, 19: 869-877.

Milani N, Dalpra L, del Prete A, Zanini R, Larizza L: A novel mutation (Gln266 - > His) in the alpha 1 subunit of the inhibitory glycine-receptor gene (GLRA1) in hereditary hyperekplexia. Am J Hum Genet. 1996, 58: 420-422.

Becker K, Breitinger HG, Humeny A, Meinck HM, Dietz B, Aksu F, Becker CM: The novel hyperekplexia allele GLRA1(S267N) affects the ethanol site of the glycine receptor. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008, 16: 223-228. 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201958.

Lapunzina P, Sanchez JM, Cabrera M, Moreno A, Delicado A, de Torres ML, Mori AM, Quero J, Lopez Pajares I: Hyperekplexia (startle disease): a novel mutation (S270T) in the M2 domain of the GLRA1 gene and a molecular review of the disorder. Mol Diagn. 2003, 7: 125-128.

Gregory ML, Guzauskas GF, Edgar TS, Clarkson KB, Srivastava AK, Holden KR: A novel GLRA1 mutation associated with an atypical hyperekplexia phenotype. J Child Neurol. 2008, 23: 1433-1438. 10.1177/0883073808320754.

Elmslie FV, Hutchings SM, Spencer V, Curtis A, Covanis T, Gardiner RM, Rees M: Analysis of GLRA1 in hereditary and sporadic hyperekplexia: a novel mutation in a family cosegregating for hyperekplexia and spastic paraparesis. J Med Genet. 1996, 33: 435-436. 10.1136/jmg.33.5.435.

Kang HC, Jeong You S, Jae Chey M, Sam Baik J, Kim JW, Ki CS: Identification of a de novo Lys304Gln mutation in the glycine receptor alpha-1 subunit gene in a Korean infant with hyperekplexia. Mov Disord. 2008, 23: 610-613. 10.1002/mds.21909.

Shiang R, Ryan SG, Zhu YZ, Fielder TJ, Allen RJ, Fryer A, Yamashita S, O’Connell P, Wasmuth JJ: Mutational analysis of familial and sporadic hyperekplexia. Ann Neurol. 1995, 38: 85-91. 10.1002/ana.410380115.

Poon WT, Au KM, Chan YW, Chan KY, Chow CB, Tong SF, Lam CW: Novel missense mutation (Y279S) in the GLRA1 gene causing hyperekplexia. Clin Chim Acta. 2006, 364: 361-362. 10.1016/j.cca.2005.09.018.

Bellini G, Miceli F, Mangano S, Miraglia Del Giudice E, Coppola G, Barbagallo A, Taglialatela M, Pascotto A: Hyperekplexia caused by dominant-negative suppression of glyra1 function. Neurology. 2007, 68: 1947-1949. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000263193.75291.85.

Jungbluth H, Rees MI, Manzur AY, Mercuri E, Sewry CA, Gobbi P, Muntoni F: An unusual case of hyperekplexia. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2000, 4: 77-80. 10.1053/ejpn.1999.0267.

Engel AG, Shen XM, Selcen D, Sine SM: What have we learned from the congenital myasthenic syndromes. J Mol Neurosci. 2010, 40: 143-153. 10.1007/s12031-009-9229-0.

Tijssen MA, Shiang R, van Deutekom J, Boerman RH, Wasmuth JJ, Sandkuijl LA, Frants RR, Padberg GW: Molecular genetic reevaluation of the Dutch hyperekplexia family. Arch Neurol. 1995, 52: 578-582. 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540300052012.

Langosch D, Laube B, Rundstrom N, Schmieden V, Bormann J, Betz H: Decreased agonist affinity and chloride conductance of mutant glycine receptors associated with human hereditary hyperekplexia. EMBO J. 1994, 13: 4223-4228.

Lynch JW, Rajendra S, Pierce KD, Handford CA, Barry PH, Schofield PR: Identification of intracellular and extracellular domains mediating signal transduction in the inhibitory glycine receptor chloride channel. EMBO J. 1997, 16: 110-120. 10.1093/emboj/16.1.110.

Maksay G, Biro T, Laube B: Hyperekplexia mutation of glycine receptors: decreased gating efficacy with altered binding thermodynamics. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002, 64: 285-288. 10.1016/S0006-2952(02)01111-5.

Rajendra S, Lynch JW, Pierce KD, French CR, Barry PH, Schofield PR: Startle disease mutations reduce the agonist sensitivity of the human inhibitory glycine receptor. J Biol Chem. 1994, 269: 18739-18742.

Rajendra S, Lynch JW, Pierce KD, French CR, Barry PH, Schofield PR: Mutation of an arginine residue in the human glycine receptor transforms beta-alanine and taurine from agonists into competitive antagonists. Neuron. 1995, 14: 169-175. 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90251-1.

Keramidas A, Moorhouse AJ, Schofield PR, Barry PH: Ligand-gated ion channels: mechanisms underlying ion selectivity. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2004, 86: 161-204. 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2003.09.002.

Colquhoun D: Binding, gating, affinity and efficacy: the interpretation of structure-activity relationships for agonists and of the effects of mutating receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 1998, 125: 924-947.

Lape R, Plested AJ, Moroni M, Colquhoun D, Sivilotti LG: The alpha1K276E startle disease mutation reveals multiple intermediate states in the gating of glycine receptors. J Neurosci. 2012, 32: 1336-1352. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4346-11.2012.

Lewis TM, Sivilotti LG, Colquhoun D, Gardiner RM, Schoepfer R, Rees M: Properties of human glycine receptors containing the hyperekplexia mutation alpha1(K276E), expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol. 1998, 507 (Pt 1): 25-40.

Schaefer N, Langlhofer G, Kluck CJ, Villmann C: Glycine receptor mouse mutants: model systems for human hyperekplexia. Br J Pharmacol. 2013, 170: 933-952. 10.1111/bph.12335.

Shan Q, Han L, Lynch JW: Function of hyperekplexia-causing alpha1R271Q/L glycine receptors is restored by shifting the affected residue out of the allosteric signalling pathway. Br J Pharmacol. 2012, 165: 2113-2123. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01701.x.

Nussinov R: Allosteric modulators can restore function in an amino acid neurotransmitter receptor by slightly altering intra-molecular communication pathways. Br J Pharmacol. 2012, 165: 2110-2112. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01793.x.

Maksay G, Biro T, Laube B, Nemes P: Hyperekplexia mutation R271L of alpha1 glycine receptors potentiates allosteric interactions of nortropeines, propofol and glycine with [3H] strychnine binding. Neurochem Int. 2008, 52: 235-240. 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.06.009.

O’Shea SM, Becker L, Weiher H, Betz H, Laube B: Propofol restores the function of “hyperekplexic” mutant glycine receptors in Xenopus oocytes and mice. J Neurosci. 2004, 24: 2322-2327. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4675-03.2004.

Nury H, Van Renterghem C, Weng Y, Tran A, Baaden M, Dufresne V, Changeux JP, Sonner JM, Delarue M, Corringer PJ: X-ray structures of general anaesthetics bound to a pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. Nature. 2011, 469: 428-431. 10.1038/nature09647.

Moorhouse AJ, Jacques P, Barry PH, Schofield PR: The startle disease mutation Q266H, in the second transmembrane domain of the human glycine receptor, impairs channel gating. Mol Pharmacol. 1999, 55: 386-395.

Castaldo P, Stefanoni P, Miceli F, Coppola G, Del Giudice EM, Bellini G, Pascotto A, Trudell JR, Harrison NL, Annunziato L, Taglialatela M: A novel hyperekplexia-causing mutation in the pre-transmembrane segment 1 of the human glycine receptor alpha1 subunit reduces membrane expression and impairs gating by agonists. J Biol Chem. 2004, 279: 25598-25604. 10.1074/jbc.M311021200.

Pless SA, Leung AW, Galpin JD, Ahern CA: Contributions of conserved residues at the gating interface of glycine receptors. J Biol Chem. 2011, 286: 35129-35136. 10.1074/jbc.M111.269027.

Breitinger HG, Villmann C, Becker K, Becker CM: Opposing effects of molecular volume and charge at the hyperekplexia site alpha 1(P250) govern glycine receptor activation and desensitization. J Biol Chem. 2001, 276: 29657-29663. 10.1074/jbc.M100446200.

Breitinger HG, Lanig H, Vohwinkel C, Grewer C, Breitinger U, Clark T, Becker CM: Molecular dynamics simulation links conformation of a pore-flanking region to hyperekplexia-related dysfunction of the inhibitory glycine receptor. Chem Biol. 2004, 11: 1339-1350. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.07.008.

Wang Q, Lynch JW: Activation and desensitization induce distinct conformational changes at the extracellular-transmembrane domain interface of the glycine receptor. J Biol Chem. 2011, 286: 38814-38824. 10.1074/jbc.M111.273631.

Villmann C, Oertel J, Melzer N, Becker CM: Recessive hyperekplexia mutations of the glycine receptor alpha1 subunit affect cell surface integration and stability. J Neurochem. 2009, 111: 837-847. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06372.x.

Villmann C, Oertel J, Ma-Hogemeier ZL, Hollmann M, Sprengel R, Becker K, Breitinger HG, Becker CM: Functional complementation of Glra1(spd-ot), a glycine receptor subunit mutant, by independently expressed C-terminal domains. J Neurosci. 2009, 29: 2440-2452. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4400-08.2009.

Laube B, Kuhse J, Rundstrom N, Kirsch J, Schmieden V, Betz H: Modulation by zinc ions of native rat and recombinant human inhibitory glycine receptors. J Physiol. 1995, 483 (Pt 3): 613-619.

Hirzel K, Muller U, Latal AT, Hulsmann S, Grudzinska J, Seeliger MW, Betz H, Laube B: Hyperekplexia phenotype of glycine receptor alpha1 subunit mutant mice identifies Zn (2+) as an essential endogenous modulator of glycinergic neurotransmission. Neuron. 2006, 52: 679-690. 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.035.

Zhou N, Wang CH, Zhang S, Wu DC: The GLRA1 missense mutation W170S associates lack of Zn2+ potentiation with human hyperekplexia. J Neurosci. 2013, 33: 17675-17681. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3240-13.2013.

Bianchi MT, Macdonald RL: Mutation of the 9′ leucine in the GABA (A) receptor gamma2L subunit produces an apparent decrease in desensitization by stabilizing open states without altering desensitized states. Neuropharmacology. 2001, 41: 737-744. 10.1016/S0028-3908(01)00132-0.

Chang Y, Weiss DS: Substitutions of the highly conserved M2 leucine create spontaneously opening rho1 gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 1998, 53: 511-523.

Chang Y, Weiss DS: Allosteric activation mechanism of the alpha 1 beta 2 gamma 2 gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor revealed by mutation of the conserved M2 leucine. Biophys J. 1999, 77: 2542-2551. 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77089-X.

Tierney ML, Birnir B, Pillai NP, Clements JD, Howitt SM, Cox GB, Gage PW: Effects of mutating leucine to threonine in the M2 segment of alpha1 and beta1 subunits of GABAA alpha1beta1 receptors. J Membr Biol. 1996, 154: 11-21. 10.1007/s002329900128.

Ganser LR, Yan Q, James VM, Kozol R, Topf M, Harvey RJ, Dallman JE: Distinct phenotypes in zebrafish models of human startle disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2013, 60: 139-151.

Lynch JW: Molecular structure and function of the glycine receptor chloride channel. Physiol Rev. 2004, 84: 1051-1095. 10.1152/physrev.00042.2003.

Acknowledgements

JWL is supported by a research fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Both authors participated in developing and discussing the ideas and in writing the manuscript. Both authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Bode, A., Lynch, J.W. The impact of human hyperekplexia mutations on glycine receptor structure and function. Mol Brain 7, 2 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-6606-7-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-6606-7-2