Abstract

Background

Molecular techniques are invaluable for investigation on the biodiversity of Anopheles mosquitoes. This study aimed at investigating the spatial-genetic variations among Anopheles mosquitoes from different areas of Peninsular Malaysia, as well as deciphering evolutionary relationships of the local Anopheles mosquitoes with the mosquitoes from neighbouring countries using the anopheline ITS2 rDNA gene.

Methods

Mosquitoes were collected, identified, dissected to check infection status, and DNA extraction was performed for PCR with primers targeting the ITS2 rDNA region. Sequencing was done and phylogenetic tree was constructed to study the evolutionary relationship among Anopheles mosquitoes within Peninsular Malaysia, as well as across the Asian region.

Results

A total of 133 Anopheles mosquitoes consisting of six different species were collected from eight different locations across Peninsular Malaysia. Of these, 65 ITS2 rDNA sequences were obtained. The ITS2 rDNA amplicons of the studied species were of different sizes. One collected species, Anopheles sinensis, shows two distinct pools of population in Peninsular Malaysia, suggesting evolvement of geographic race or allopatric speciation.

Conclusion

Anopheles mosquitoes from Peninsular Malaysia show close evolutionary relationship with the Asian anophelines. Nevertheless, genetic differences due to geographical segregation can be seen. Meanwhile, some Anopheles mosquitoes in Peninsular Malaysia show vicariance, exemplified by the emergence of distinct cluster of An. sinensis population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Anopheles mosquitoes are one of the most studied members of the Culicidae family. The discovery of Anopheles as the exclusive vector for malaria transmission in humans has garnered much attention to study this particular genus. Due to insecticide usage in malaria control programs and agricultural practices, Anopheles mosquitoes are subjected to high mutation rate and selective pressure [1–3]. Besides, geographical barriers such as mountains and seas cause vicariance [4], thus preventing genetic interchange among Anopheles of the same species from different locations or countries. Occasionally, these phenomena drive speciation, where the new population shows biological characteristics that are different from the parent species [5, 6]. Such biological differences include degree of resistance against insecticides, susceptibility to malaria parasites and capability in malaria transmission. In view of this, the population and evolutionary dynamics of Anopheles mosquitoes deserve research attention, especially in countries that are at the edge of complete malaria eradication, exemplified by Malaysia.

Molecular technique provides a powerful tool for effective investigation on the population dynamics of mosquitoes. It enables more detailed understanding on the relationships between the vectorial capacity, genetic makeup and geographical origin for a particular species of Anopheles, more detailed and precise taxonomy, as well as evolutionary studies [6–10]. Various gene markers have been selected for such study purposes. Gene sequences such as Internal Transcribed Spacer 1 and 2 (ITS1 & 2) of ribosomal DNA (rDNA), mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I and II (COI & COII), and D3 (28S rDNA) are helpful in species identification and phylogenetic analyses [10–25]. Among these gene sequences, the ITS2 of rDNA (ITS2 rDNA) has been found to be valuable for taxonomic classification [24, 26–29]. ITS2 rDNA is a non-coding DNA sequence. Therefore, it is subjected to a high degree of mutations, which makes it a good candidate to study phylogenetics of closely related Anopheles species, as well as biodiversity and geographic races of a particular species of mosquitoes [30]. To date, the ITS2 rDNA sequences have been successfully used to distinguish members of several Anopheles species complexes, such as An. hyrcanus group [24], An. dirus complex [12] and An. maculatus group [31]. Regrettably, knowledge regarding Malaysian Anopheles population characterization based on ITS2 rDNA is not well established [31–38]. Hence, there is a need to fill this knowledge gap for better understanding on biodiversity of Anopheles in this region based on ITS2 rDNA.

This study aimed at characterizing the ITS2 rDNA sequences of several Anopheles mosquitoes in Peninsular Malaysia, as well as investigating the spatial-genetic variations among Anopheles mosquitoes from different areas of Peninsular Malaysia. Besides, this study also aimed at deciphering the evolutionary relationship of the local Anopheles mosquitoes with the mosquitoes from other Asian countries.

Methods

Mosquito collection and identification

This study was approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of University of Malaya [PAR/19/02/2013/AA (R)]. Mosquitoes were collected from twenty locations across eight states of Peninsular Malaysia using the bare-leg catch (BLC) method and human-bait net trapping method as described previously [39, 40]. Collection sites were selected based on previous studies [41, 42], as well as information regarding malaria case incidence provided by the District Health Offices of respective states. Collection was conducted from hour 1800 to 2330. The captured mosquitoes were kept in a glass tube containing moist tissue for further processing in the laboratory. Anopheles mosquitoes were sorted from the collected mosquitoes, subsequently differentiated into species based on taxonomy morphological keys, with the aid of a stereomicroscope as described previously [43, 44]. Dissection, coupled with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed on the captured Anopheles mosquitoes to investigate the infection status by the malaria parasites as described in a previous study [45].

Mosquito DNA extraction and amplification

DNA extraction was conducted with DNeasy® Blood & Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The final DNA product was dissolved in 60 μL elution buffer and stored at −20°C until PCR analysis.

Sequences of ITS2 rDNA from extracted DNA of each Anopheles mosquito were amplified using the primers and protocols developed previously [12]. Briefly, reactions were performed using MyCycler™ Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, USA). Each reaction mixture of 25 μL contained 4 μL of mosquito DNA template, primers ITS2A (5’ TGT GAA CTG CAG GAC A 3’) and ITS2B (5’ TAT GCT TAA ATT CAG GGG GT 3’), 0.2 μM respectively, 0.2 mM dNTP, 4 mM MgCl2, 10 μL of GoTaq® Flexi Buffer and 1.25 U of GoTaq® DNA polymerase (Promega, USA). The PCR conditions were as follows: (1) denaturation at 94°C for 5 minutes, (2) 35 cycles of amplification at 94°C for 1 minute, annealing step at 51°C for 1 minute with elongation step at 72°C for 2 minutes, followed by (3) final elongation step of 10 minutes at 72°C and a hold temperature of 4°C.

DNA sequencing and analysis

The PCR amplicons were ligated to pGEM®-T vector (Promega, USA) and transformed into One Shot® TOP10 Escherichia coli competent cells (Invitrogen™, USA). Recombinant plasmid was extracted and purified using QIAprep® Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen, USA). ITS2 rDNA was sequenced using the M13 forward (−20) and reverse (−24) universal sequencing primers. Sequences were edited using UGENE software and aligned in ClustalW program using the default parameters. By using Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) [46], sequence identity comparison and confirmation were carried out using gene sequence read archive (SRA) of GenBank. Subsequently, multiple sequence alignment of ITS2 rDNA was conducted and Neighbor-Joining (bootstrap = 1000) [47] and Maximum Parsimony analysis [48] were employed to study the evolutionary relationship among Anopheles mosquitoes within Malaysia, as well as across the Asian region.

Results

In total, 133 Anopheles mosquitoes consisting of six different species were collected from eight different locations across Peninsular Malaysia (Figure 1, Additional file 1: Table S1). These Anopheles mosquitoes were collected from suburban, rural and forested areas. The collected Anopheles species were An. cracens, An. maculatus, An. karwari, An. barbirostris, An. sinensis and An. peditaeniatus. All specimens were negative for Plasmodium sporozoite infection from dissection and PCR.

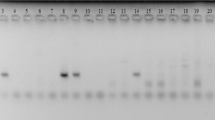

From these mosquitoes, 65 ITS2 rDNA sequences were obtained. Amplicons with consistently distinct sizes were yielded from each species, with An. cracens being 855 bp; An. maculatus being 460 bp; An. karwari being 526 bp; An. barbirostris with 1576 bp; An. sinensis yielding 575 bp; and An. peditaeniatus being 583 bp (Figure 2). Sequence alignment of An. barbirostris was difficult due to several reasons. Firstly, there are many variable length nucleotide sequence repeats within ITS2 rDNA of An. barbirostris. Besides, the An. barbirostris ITS2 rDNA sequence range covered by ITS2A and ITS2B primer set is too long (1576 bp), causing low resolution of nucleotide reading in both one-way and two-way sequencing methods. As a result, another forward sequencing primer, ITS2M (5’ GCG TGG TCT ACT AGT TAG AC 3’) was designed to target nucleotide sequences in the middle range of the amplicon, thus increasing the nucleotide reading resolution in sequencing. For phylogenetic comparison between anophelines across Asian regions, anopheline ITS2 sequences from other countries that are available in GenBank were used for phylogeny tree construct and analysis (Figure 3).

Gel pictures showing PCR amplicons generated from the six Anopheles species using ITS2A and ITS2B primers. Different species show amplicons of different sizes. Lane L1 denotes lane with DNA ladders of 100 bp whereas lane L2 indicates lane with DNA ladders of 1000 bp. The right-most lane of each picture represents the “no-template control”. Agarose gels of 1.5 % (A-C) and 1.3 % (D) were used. The amplicons of An. maculatus (lane 1 – 4) and An. karwari (lane 5 – 12) were shown to be 460 bp and 526 bp respectively (A). For An. peditaeniatus (lane 1) and An. sinensis (lane 2 & 3), amplicons were of 583 bp and 575 bp respectively (B). Specimens of An. cracens (lane 1 – 5) were shown to yield amplicons of 855 bp (C). Amplicons of An. barbirostris specimens (lane 1 & 2) were 1576 bp long (D).

By analyzing sequences obtained from cloning, coupled with reference sequences from GenBank, point mutations were found in all collected species, with An. karwari showing the highest prevalence (22 point mutations detected), followed by An. barbirostris (19 point mutations detected), An. maculatus (12 point mutations detected), An. cracens (10 point mutations detected), An. peditaeniatus (6 point mutations detected), An. sinensis from northern Peninsular Malaysia (3 point mutations detected), and An. sinensis from central Peninsular Malaysia (1 point mutation detected). In addition, other forms of mutations such as deletion (in all six species studied), insertion (in An. cracens, An. barbirostris, An. karwari and An. sinensis), duplication (in An. cracens and An. barbirostris) and small tandem repeats (in all six species studied) were found as well. Interestingly, two sets of ITS2 rDNA nucleotide sequences (with size difference of 2 bp) with distinctive patterns of mutations (insertions and deletions) were found in each specimen of An. karwari (Figure 4).

Based on sequence alignment and comparison, ITS2 rDNA sequences from the collected An. cracens showed no obvious nucleotide sequence variation. Due to lack of ITS2 rDNA sequences of An. cracens from other countries, phylogenetic analysis on this particular species could not be conducted. Nevertheless, ITS2 rDNA sequences of two related species [12, 49], An. dirus (formerly known as An. dirus A) and An. baimaii (formerly known as An. dirus D) from GenBank were recruited for the phylogenetic analysis. As expected, An. cracens is closely related but distinct from An. dirus and An. baimaii. Likewise, obvious geographical clustering was not detected among An. maculatus from Peninsular Malaysia, as well as with those of other Asian countries. Nevertheless, An. maculatus ITS2 rDNA sequences show clear difference but close relationship with other members from An. maculatus complex (An. dispar, An. greeni, An. sawadwongporni, An. rampae, An. dravidicus, An. pseudowillmori and An. willmori) [31, 50–52]. From the phylogenetic tree, An. karwari shows a relatively close relationship with An. maculatus group. This should not be too surprising since An. karwari shows high resemblance to An. maculatus in morphological features. For An. barbirostris, all five clades of An. barbirostris complex were included for the analysis. The An. barbirostris specimens collected from this study were most closely related to Clade IV. By comparison, members from Clade I, as well as Clade V (also known as An. campestris) are the most distantly apart from An. barbirostris specimens collected from this study.

As mentioned earlier, the collected An. karwari showed distinct patterns of mutations. Indeed, the mutation pattern seen in the collected Peninsular Malaysian An. karwari was different from that of Sri Lankan An. karwari (sequences from GenBank) [53]. Meanwhile, An. barbirostris collected were related, but distinct from the Thai and Indonesian An. barbirostris. Interestingly, An. sinensis obtained from two distantly apart locations in Malaysia (northern Peninsular Malaysia and central Peninsular Malaysia) were depicted as two distinctive clusters, with the cluster originated from central Peninsular Malaysia situated closer to clusters from the oriental region (South Korea, China and Japan) and other Southeast Asian countries (Thailand and Singapore). Only one An. peditaeniatus was collected throughout the study. Since the An. peditaeniatus ITS2 rDNA sequences from other countries that are archived in GenBank are too short [54], phylogenetic comparison of the An. peditaeniatus population could not be conducted.

Discussion

In this study, Plasmodium sporozoite-positive Anopheles were not found. This may be due to several reasons. Firstly, the population of Anopheles mosquitoes infected with Plasmodium sporozoites may be very small, and such a small portion of infected Anopheles is likely to be missed in the fieldwork. Indeed, the malaria transmission in Peninsular Malaysia has been reduced to very low levels and malaria cases only occur sporadically [55]. Hence the probability of finding Anopheles positive with Plasmodium sporozoite is also low. Coupled with the relatively small sampling size of this study, the chance of getting an infected Anopheles mosquito is even smaller. In addition, the exact geographical source of infection reported by patients to the District Health Offices may not be accurate.

The sizes of amplicons obtained from this study vary from one species to another, indicating a high rate of insertion and deletion (INDEL) mutations on this gene. Four species (An. maculatus, An. karwari, An. sinensis and An. peditaeniatus) fall into the range of 460 to 583 bp, whereas An. cracens and An. barbirostris yield much larger amplicons (855 and 1576 bp respectively). As mentioned earlier, An. barbirostris has many variable length nucleotide sequence repeats within its ITS2 rDNA. This finding is parallel to those reported previously [15, 56]. For An. cracens, the larger size amplicon is due to duplication of nucleotide sequences. Indeed, the yield of larger amplicons with ITS2 primers is also found in other members of An. leucosphyrus group (e.g. An. dirus and An. baimaii) [49, 57].

Point mutations were detected in all species of anophelines collected in this study, albeit with different rates. It is important to note that “point mutation-like” single nucleotide differences may arise from Taq polymerase and sequencing errors. Nevertheless, such probability was ruled out in this study. Prior to this study, an independent experiment was conducted on a well conserved gene using the same Taq polymerase used in this study (data not shown). The conserved gene cloned in plasmid was amplified using the same Taq polymerase and cloned into pGEM®-T vector. Three clones were selected for sequencing. Each set showed 100% identity with the original recombinant plasmid carrying the conserved gene sequence. This indicates that the Taq polymerase used in this study is reliable for nucleotide sequence analysis.

The lack of apparent nucleotide sequence variation among ITS2 rDNA sequences of the collected An. cracens may be due to the fact that all An. cracens specimens were collected from separate, but adjoining forested areas within the state of Pahang. Therefore, the genetic interchange between the An. cracens from these locations is not impeded. On the other hand, the presence of two distinct sets of ITS2 rDNA sequences in each An. karwari is possibly due to the multiple copies of ITS2 within rDNA of each mosquito, where two distinct mutations arise. In this study, sequences archived by previous study on Sri Lankan An. karwari were recruited for phylogenetic analysis [53]. The analyses showed that the mutation patterns of Peninsular Malaysian An. karwari were different from that of the Sri Lankan An. karwari. Interestingly, the Sri Lankan An. karwari was shown to be distinct from An. karwari from other Asian countries (India, Myanmar and Cambodia) based on mitochondrial DNA analysis [53]. Therefore, it is possible that the mutation pattern found in An. karwari collected from this study would bear more resemblance to that of An. karwari from those countries, as compared to the Sri Lankan An. karwari. However, further studies are needed to verify this observation.

One critical difficulty in phylogenetic tree construct for this study is the inadequate amount of usable nucleotide sequences from other countries. Some of the archived sequences are too short while some other sequences are of different gene regions that offer small, if not zero overlapping with our nucleotide sequences. Indeed, such difficulty is also mentioned by a previous study [29]. Nevertheless, a phylogenetic tree was constructed by using the available resources. Based on the phylogenetic tree constructed, all Anopheles mosquitoes from Peninsular Malaysia show close phylogenetic relationship with the same species of Anopheles from Asian regions, especially the mainland countries. The relatively closer relationship with nearer mainland countries than the Asian islets shows that geographical isolation confers distinctive genetic pools to the mosquitoes on the islets, resulting in bigger genetic difference with those from the mainland. For instance, An. greeni and An. dispar are two species on the Philippines that are evolved from An. maculatus due to long period of geographical isolation [50]. Nevertheless, islets that are very close to Peninsular Malaysia like Singapore still have mosquitoes that are genetically close to Peninsular Malaysian mosquitoes [15, 58]. At the same time, places from the mainland that are well isolated by mountains harbour mosquitoes with distinctive genotypes as well. This is well exemplified by the phylogenetic analysis of An. barbirostris in this study. The An. barbirostris captured from this study showed close relationship with those from Muang District of Trat Province, Thailand [15], which is located at the Gulf of Thailand. Meanwhile, these Peninsular Malaysian mosquitoes are quite different from the An. barbirostris of Indonesian Sumatra, as well as those from Sa Kaeo Province and Mae Hong Son Province of Thailand [15]. As Indonesian Sumatra is separated from Peninsular Malaysia by the Strait of Malacca while Sa Kaeo and Mae Hong Son are valleys isolated by mountains and thick forests, it is not surprising that the Anopheles mosquitoes from these locations are more distantly apart from the Peninsular Malaysian Anopheline mosquitoes in phylogenetic analysis.

Interestingly, An. sinensis collected from Kelantan (northern Peninsular Malaysia) were distinct from An. sinensis of central Peninsular Malaysia and other Asian countries. Such difference suggests development of distinct geographic races or allopatric speciation evolvement of these An. sinensis populations due to long periods of complete geographical isolation. The two sampling locations are separated by highlands such as the Tahan Range and Titiwangsa Mountains (Sankalakhiri Range). Geographical segregation (vicariance) prevents genetic flow, interchange and interaction between population pools of a same species. Consequently, these distinguished pools of mosquito populations evolve and show genetic differences. Indeed, An. belenrae and An. kleini were upgraded to distinct species from the South Korean An. sinensis population via ITS2 rDNA study [24, 59]. Nevertheless, the status of this group of Kelantanese An. sinensis remains to be validated. More gene markers such as ND6, COI and COII should be tested to verify its actual taxonomical status [15, 17].

Another interesting point worth mentioning here is the capture of An. barbirostris via BLC technique from this study. In Peninsular Malaysia, An. barbirostris is regarded as a zoophilic mosquito [60]. However, this species was collected easily using BLC in locations adjacent to housing areas. This suggests that the feeding behaviour of An. barbirostris has changed and adapted to human blood feeding. Since this species is one of the major malaria vectors in Timor Leste [61], more attention should be given to study the sporozoite infectivity of An. barbirostris in Peninsular Malaysia.

Conclusion

Based on this study, Anopheles mosquitoes from Peninsular Malaysia show close evolutionary relationship with the Asian anophelines. Nevertheless, genetic differences can be seen between the Peninsular Malaysian Anopheles and the Anopheles of certain places of this region due to geographical segregation. In addition, populations of some Anopheles mosquitoes in Peninsular Malaysia show divergent evolutionary progress, exemplified by the emergence of distinct cluster of An. sinensis populations due to geographical segregation, suggestive of allopatric speciation.

References

Stump AD, Fitzpatrick MC, Lobo NF, Traoré S, Sagnon N, Costantini C, Collins FH, Besansky NJ: Centromere-proximal differentiation and speciation in Anopheles gambiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005, 102: 15930-15935.

Pinto J, Lynd A, Vicente JL, Santolamazza F, Randle NP, Gentile G, Moreno M, Simard F, Charlwood JD, do Rosário VE, Caccone A, Torre A, Donnelly MJ: Multiple origins of knockdown resistance mutations in the Afrotropical mosquito vector Anopheles gambiae. PLoS ONE. 2007, 2: e1243.

Boakye DA, Adasi K, Appawu M, Brown CA, Wilson MD: Patterns of household insecticide use and pyrethroid resistance in Anopheles gambiae sensu stricto (Diptera: Culicidae) within the Accra metropolis of Ghana. Afr Entomol. 2009, 17: 125-130.

Krzywinski J, Besansky NJ: Molecular systematics of Anopheles: from subgenera to subpopulations. Annu Rev Entomol. 2003, 48: 111-139.

Mirabello L, Conn JE: Molecular population genetics of the malaria vector Anopheles darlingi in Central and South America. Heredity. 2006, 96: 311-321.

Kamali M, Xia A, Tu Z, Sharakhov IV: A new chromosomal phylogeny supports the repeated origin of vectorial capacity in malaria mosquitoes of the Anopheles gambiae complex. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8: e1002960.

Wistow G: Lens crystallins: gene recruitment and evolutionary dynamism. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993, 18: 301-306.

Jermann TM, Optiz JG, Stackhouse J, Bennner SA: Reconstructing the evolutionary history of the artiodactyl ribonuclease superfamily. Nature. 1995, 374: 57-59.

Chandrasekharan UM, Sanker S, Glynias MJ, Karnik SS, Husain A: Angiotensin II-forming activity in a reconstructed ancestral chymase. Science. 1996, 271: 502-505.

Kaura T, Sharma M, Chaudhry S, Chudhry A: Sequence polymorphism in spacer ITS2 of Anopheles (Cellia) subpictus Grassi (Diptera: Culicidae). Caryologia. 2010, 63: 124-133.

Cornel AJ, Porter CH, Collins FH: Polymerase chain reaction species diagnostic assay for Anopheles quadrimaculatus cryptic species (Diptera: Culicidae) based on ribosomal DNA ITS2 sequences. J Med Entomol. 1996, 33: 109-116.

Walton C, Hardley JM, Kuvangkadilok C, Collins FH, Harbach RE, Baimai V, Butlin RK: Identification of five species of the Anopheles dirus complex from Thailand, using allele-specific polymerase chain reaction. Med Vet Entomol. 1999, 13: 24-32.

Garros C, Koekemoer LL, Coetzee M, Coosemans M, Manguin S: A single multiplex assay to identify major malaria vectors within the African Anopheles funestus and the Oriental An. minimus groups. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004, 70: 583-590.

Sallum MAM, Foster PG, Li C, Sithiprasasna R, Wilkerson RC: Phylogeny of the Leucosphyrus Group of Anopheles (Cellia) (Diptera: Culicidae) based on mitochondrial gene sequences. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 2007, 100: 27-35.

Paredes-Esquivel C, Donnelly MJ, Harbach RE, Townson H: A molecular phylogeny of mosquitoes in the Anopheles barbirostris Subgroup reveals cryptic species: implications for identification of disease vectors. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2009, 50: 141-151.

Mohanty A, Swain S, Kar SK, Hazra RK: Analysis of the phylogenetic relationship of Anopheles species, subgenus Cellia (Diptera: Culicidae) and using it to define the relationship of morphologically similar species. Infect Genet Evol. 2009, 9: 1204-1224.

Takano KT, Nguyen NT, Nguyen BT, Sunahara T, Yasunami M, Nguyen MD, Takagi M: Partial mitochondrial DNA sequences suggest the existence of a cryptic species within the Leucosphyrus group of the genus Anopheles (Diptera: Culicidae), forest malaria vectors, in Northern Vietnam. Parasit Vectors. 2010, 3: 41.

Sarma DK, Prakash A, O'Loughlin SM, Bhattacharyya DR, Mohapatra PK, Bhattacharjee K, Das K, Singh S, Sarma NP, Ahmed GU, Walton C, Mahanta J: Genetic population structure of the malaria vector Anopheles baimaii in north-east India using mitochondrial DNA. Malar J. 2012, 11: 76.

Huang ZH, Wang JF: [Cloning and sequencing of cytochrome c oxidase II(COII) gene of three species of mosquitoes] (in Chinese). Zhongguo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi. 2001, 19: 90-92.

Whang IJ, Jung J, Park JK, Min GS, Kim W: Intragenomic length variation of the ribosomal DNA intergenic spacer in a malaria vector, Anopheles sinensis. Mol Cells. 2002, 31: 158-162.

Min GS, Choochote W, Jitpakdi A, Kim SJ, Kim W, Jung J, Junkum A: Intraspecific hybridization of Anopheles sinensis (Diptera: Culicidae) strains from Thailand and Korea. Mol Cells. 2002, 31: 198-204.

Park SJ, Choochote W, Jitpakdi A, Junkum A, Kim SJ, Jariyapan N, Park JW, Min GS: Evidence for a conspecific relationship between two morphologically and cytologically different forms of Korean Anopheles pullus mosquito. Mol Cells. 2003, 31: 354-360.

Wilkerson RC, Li C, Rueda LM, Kim HC, Klein TA, Song GH, Strickman D: Molecular confirmation of Anopheles (Anopheles) lesteri from the Republic of South Korea and its genetic identity with An. (Ano.) anthropophagus from China (Diptera: Culicidae). Zootaxa. 2003, 378: 1-14.

Li C, Lee JS, Groebner JL, Kim HC, Klein TA, O’Guinn ML, Wilkerson RC: A newly recognized species in the Anopheles Hyrcanus Group and molecular identification of related species from the Republic of South Korea (Diptera: Culicidae). Zootaxa. 2005, 939: 1-8.

Park MH, Choochote W, Kim SJ, Somboon P, Saeung A, Tuetan B, Tsuda Y, Takagi M, Joshi D, Ma Y, Min GS: Nonreproductive isolation among four allopatric strains of Anopheles sinensis in Asia. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2008, 24: 489-495.

Coleman AW: ITS2 is a double-edged tool for eukaryote evolutionary comparison. Trends Genet. 2003, 19: 370-375.

Alvarez I, Wendel JF: Ribosomal ITS sequences and plant phylogenetic inference. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2003, 29: 417-434.

Linton YM, Dusfour I, Howard TM, Ruiz LF, Duc Manh N, Ho Dinh T, Sochanta T, Coosemans M, Harbach RE: Anopheles (Cellia) epiroticus (Diptera: Cullicidae) a new malaria vector species in the Southeast Asia Sundaicus complex. Bull Entomol Res. 2005, 95: 329-339.

Sinka ME, Bangs MJ, Manguin S, Chareonviriyaphap T, Patil AP, Temperley WH, Gething PW, Elyazar IR, Kabaria CW, Harbach RE, Hay SI: The dominant Anopheles vectors of human malaria in the Asia-Pacific region: occurrence data, distribution maps and bionomic précis. Parasit Vectors. 2011, 4: 89.

Marrelli MT, Sallum MA, Marinotti O: The second internal transcribed spacer of nuclear ribosomal DNA as a tool for Latin American anopheline taxonomy- a critical review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2006, 101: 817-832.

Walton C, Somboon P, O’Loughlin SM, Zhang S, Harbach RE, Linton YM, Chen B, Nolan K, Duong S, Fong MY, Vythilingum I, Mohammed ZD, Trung HD, Butlin RK: Genetic diversity and molecular identification of mosquito species in the An. maculatus group using ITS2 region of rDNA. Infect Genet Evol. 2007, 7: 93-102.

Jit Singh P: M.Sc. thesis. Molecular identification and characterization of the malarial vector (Anopheles maculatus) in Malaysia. 2008, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: University of Malaya, Science Faculty

Yong HS, Chiang GL, Loong KP, Ooi CS: Genetic variation in the malaria mosquito vector Anopheles maculatus from Peninsular Malaysia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1988, 19: 681-687.

Manguin S, Kengne P, Sonnier L, Harbach RE, Baimai V, Trung HD, Coosemans M: SCAR markers and multiplex PCR-based identification of isomorphic species in the Anopheles dirus complex in Southeast Asia. Med Vet Entomol. 2002, 16: 46-54.

Dusfour I, Michaux JR, Harbach RE, Manguin S: Speciation and phylogeography of the Southeast Asian Anopheles sundaicus complex. Infect Genet Evol. 2007, 7: 484-493.

Rohani A, Chan ST, Abdullah AG, Tanrang H, Lee HL: Species composition of mosquito fauna in Ranau, Sabah, Malaysia. Trop Biomed. 2008, 25: 232-236.

Rohani A, Wan Najdah WM, Zamree I, Azahari AH, Mohd Noor I, Rahimi H, Lee HL: Habitat characterization and mapping of Anopheles maculatus (Theobald) mosquito larvae in malaria endemic areas in Kuala Lipis, Pahang, Malaysia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2010, 41: 821-830.

Ali WN, Ahmad R, Nor ZM, Ismail Z, Lim LH: Population dynamics of adult mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in malaria endemic villages of Kuala Lipis, Pahang, Malaysia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2011, 42: 259-267.

Mboera LE, Kihonda J, Braks MA, Knols BG: Short report: Influence of centers for disease control light trap position, relative to a human-baited bed net, on catches of Anopheles gambiae and Culex quinquefasciatus in Tanzania. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998, 59: 595-596.

Hii JL, Smith T, Mai A, Ibam E, Alpers MP: Comparison between anopheline mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) caught using different methods in a malaria endemic area of Papua New Guinea. Bull Entomol Res. 2000, 90: 211-219.

Vythilingam I, Noorazian YM, Huat TC, Jiram AI, Yusri YM, Azahari AH, Norparina I, Noorrain A, Lokmanhakim S: Plasmodium knowlesi in humans, macaques and mosquitoes in peninsular Malaysia. Parasites & Vectors. 2008, 1: 26.

Braima KA, Sum JS, Ghazali AR, Muslimin M, Jeffery J, Lee WC, Shaker MR, Elamin AE, Jamaiah I, Lau YL, Rohela M, Kamarulzaman A, Sitam F, Mohd-Noh R, Abdul-Aziz NM: Is there a risk of suburban transmission of malaria in Selangor, Malaysia?. PLoS One. 2013, 8: e77924.

Reid JA: Anopheline mosquitoes of Malaya and Borneo. Stud Inst Med Res Malaysia. 1968, 31: 80-390.

Jeffery J, Rohela M, Muslimin M, Abdul Aziz SMN, Jamaiah I, Kumar S, Tan TC, Lim YAL, Nissapatorn V, Abdul Aziz NM: Illustrated keys: some mosquitoes of Peninsular Malaysia. 2012, Malaysia: University of Malaya Press

Singh B, Bobogare A, Cox-Singh J, Snounou G, Abdullah MS, Rahman HA: A genus and species-specific nested polymerase chain reaction malaria detection assay for epidemiologic studies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999, 60: 687-692.

BLAST. [http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov]

Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S: MEGA 4: evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007, 24: 1596-1599.

Fitch WM: Toward defining the course of evolution: minimum change for a specific tree topology. Syst Zool. 1971, 20: 406-416.

Xu JN, Qu FY: Ribosomal DNA difference between species A and D of the Anopheles dirus complex of mosquitoes from China. Med Vet Entomol. 1997, 11: 134-138.

Torres EP, Foley DH, Saul A: Ribosomal DNA sequence markers differentiate two species of the Anopheles maculatus (Diptera: Culicidae) complex in the Philippines. J Med Entomol. 2000, 37: 933-937.

Ma Y, Qu F, Dong X, Zhou H: [Molecular identification of Anopheles maculatus complex from China] (in Chinese). Chin J Parasitol Dis. 2002, 20: 321-324.

Singh S, Prakash A, Yadav RN, Mohapatra PK, Sarma NP, Sarma DK, Mahanta J, Bhattacharyya DR: Anopheles (Cellia) maculatus group: its spatial distribution and molecular characterization of member species in north-east India. Acta Trop. 2012, 124: 62-70.

Morgan K, O’Loughlin SM, Fong MY, Linton YM, Somboon P, Min S, Htun PT, Nambanya S, Weerasinghe I, Sochantha T, Prakash A, Walton C: Molecular phylogenetics and biogeography of the Neocellia Series of Anopheles mosquitoes in the Oriental Region. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2009, 52: 588-601.

Paredes-Esquivel C, Harbach RE, Townson H: Molecular taxonomy of members of the Anopheles hyrcanus group from Thailand and Indonesia. Med Vet Entomol. 2011, 25: 348-352.

APMEN: Country briefing: eliminating malaria in Malaysia. 2013, [http://apmen.org/storage/country-briefings/Malaysia.pdf]

Otsuka Y: Variation in number and formation of repeat sequences in the rDNA ITS2 region of five sibling species in the Anopheles barbirostris complex in Thailand. J Insect Sci. 2011, 11: 1-11.

Prakash A, Sarma DK, Bhattacharyya DR, Mohapatra PK, Bhattacharjee K, Das K, Mahanta J: Spatial distribution and r-DNA second internal transcribed spacer characterization of Anopheles dirus (Diptera: Culicidae) complex species in north-east India. Acta Trop. 2010, 114: 49-54.

Ng LC, Lee KS, Tan CH, Ooi PL, Lam-Phua SG, Lin R, Pang SC, Lai YL, Solhan S, Chan PP, Wong KY, Ho ST, Vythilingam I: Entomologic and molecular investigation into Plasmodium vivax transmission in Singapore, 2009. Malar J. 2010, 9: 305.

Rueda LM: Two new species of Anopheles (Anopheles) Hyrcanus Group (Diptera: Culicidae) from the Republic of South Korea. Zootaxa. 2005, 941: 1-26.

Sandosham AA, Thomas V: Malariology with special reference to Malaya. 1982, Kent Ridge, Singapore: Singapore University Press

Cooper RD, Edstein MD, Frances SP, Beebe NW: Malaria vectors of Timor-Leste. Malar J. 2010, 9: 4.

Acknowledgements

JSS, WCL, YLL and MYF were supported by University of Malaya High Impact Research (HIR) Grant UM-MOHE (UM.C/625/1/HIR/MOHE/CHAN/14/3) from the Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia. WCL and JSS were supported by University of Malaya Student Research Grant PV044/2012A. NMAA and JJ were supported by University Malaya Research Grant (UMRG) (RG509-13HTM). NMAA and KAB were supported by University Malaya Postgraduate Research Fund (PPP) PV052/2012A. We would like to express our gratitude to the District Health Offices across the Peninsular Malaysia. Part of the work in this manuscript was used for poster presentation in the 6th ASEAN Congress on Tropical Medicine & Parasitology (ACTMP) 2014, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JSS, AA, JJ, NMAA and KAB conducted fieldwork for mosquito collection. JSS conducted and processed molecular diagnoses. JSS, WCL and MYF collected, analyzed and interpreted the data. JSS, WCL and MYF constructed and analyzed phylogenetic tree. WCL, JSS, MYF and YLL arranged the data, conceptualized and prepared the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Sum, JS., Lee, WC., Amir, A. et al. Phylogenetic study of six species of Anopheles mosquitoes in Peninsular Malaysia based on inter-transcribed spacer region 2 (ITS2) of ribosomal DNA. Parasites Vectors 7, 309 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-309

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-309