Abstract

Background

Mosquito fitness is determined largely by body size and nutritional reserves. Plasmodium infections in the mosquito and resultant transmission of malaria parasites might be compromised by the vector’s nutritional status. We studied the effects of nutritional stress and malaria parasite infections on transmission fitness of Anopheles mosquitoes.

Methods

Larvae of Anopheles gambiae sensu stricto and An. stephensi were reared at constant density but with nutritionally low and high diets. Fitness of adult mosquitoes resulting from each dietary class was assessed by measuring body size and lipid, protein and glycogen content. The size of the first blood meal was estimated by protein analysis. Mosquitoes of each dietary class were fed upon a Plasmodium yoelii nigeriensis-infected mouse, and parasite infections were determined 5 d after the infectious blood meal by dissection of the midguts and by counting oocysts. The impact of Plasmodium infections on gonotrophic development was established by dissection.

Results

Mosquitoes raised under low and high diets emerged as adults of different size classes comparable between An. gambiae and An. stephensi. In both species low-diet females contained less protein, lipid and glycogen upon emergence than high-diet mosquitoes. The quantity of larval diet impacted strongly upon adult blood feeding and reproductive success. The prevalence and intensity of P. yoelii nigeriensis infections were reduced in low-diet mosquitoes of both species, but P. yoelii nigeriensis impacted negatively only on low-diet, small-sized An. gambiae considering survival and egg maturation. There was no measurable fitness effect of P. yoelii nigeriensis on An. stephensi.

Conclusions

Under the experimental conditions, small-sized An. gambiae expressed high mortality, possibly caused by Plasmodium infections, the species showing distinct physiological concessions when nutrionally challenged in contrast to well-fed, larger siblings. Conversely, An. stephensi was a robust, successful vector regardless of its nutrional status upon emergence. The data suggest that small-sized An. gambiae, therefore, would contribute little to malaria transmission, whereas this size effect would not affect An. stephensi.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lifetime fitness of adult female mosquitoes is influenced strongly by nutrition during larval development, the availability and quality of blood meals, and ambient conditions. Larval nutrition determines metabolic reserves and the size of adult mosquitoes upon emergence[1–3] and superimposed on body size, the number of eggs is largely governed by the size of the preceding blood meal[4]. Anopheline larvae that develop in overcrowded conditions or suffer nutritional stress result in adult mosquitoes that may require two or more blood meals before they can initiate oogenesis and lay eggs[2]. These pre-gravid mosquitoes[5] feed soon after emergence and are likely to return for a blood meal the next day. This state is common in natural populations of Anopheles gambiae, with as many as 70% of the females emerging as pre-gravid adults[5]. However, the pre-gravid condition is less common in other anophelines, perhaps with the exception of An. funestus[1, 6].

Malarial parasites are often considered detrimental to survival and gonotrophic development in anophelines (reviewed by[7, 8] and[9]). It is inferred that responses initiated by the female mosquito following an infectious blood meal negatively affect survival and vitellogenin deposition in the oocytes[10, 11]. However, while Plasmodium-infected mosquitoes may exhibit reduced longevity and fecundity, the interaction of these effects with fitness upon emergence (i.e. viable reproductive output) remain unexplored[12, 13].

Here we investigate the effects of larval nutrition upon adult characteristics on emergence of An. gambiae and An. stephensi. We also examine the effects of different larval nutritional regimes on mosquitoes uninfected or infected with the rodent malaria parasite, Plasmodium yoelii nigeriensis. We demonstrate that the two mosquito species have differing ecophysiological strategies and show that malaria transmission is possibly severely compromised in nutritionally deficient An. gambiae.

Methods

Mosquitoes

Anopheles gambiae sensu stricto (Suakoko strain) and An. stephensi (SDA500) were kept at 27°C, 80% RH, and 12 h scotophase, with 30 min dusk and dawn periods. Larvae were raised in 2.5 L of tapwater (22 x 34 cm surface area, 3.3 cm depth) and fed powdered Tetramin® fishfood (Tetrawerke, Melle, Germany) daily. Pupae were placed in 30 cm3 gauze cages for adult emergence. Adult males and females were kept together and provided with 8% fructose ad libitum. For colony maintenance, female mosquitoes were blood-fed on a human arm (An. gambiae) or an anaesthetised mouse (An. stephensi) twice per week. Eggs were collected on moist filter paper and transferred to larval trays for hatching.

For experiments, 200 newly emerged larvae were placed each in a tray and fed 0.1 mg (low diet) or 0.3 mg (high diet) powdered Tetramin® fish food per larva per day. All pupae were collected daily and placed in emergence cages. To ensure all females were mated, 6–7 d old males from the main colony were added to females (1:1 ratio) on the day of emergence.

Mosquito size

Adult mosquitoes <24 h old were killed by freezing, placed in small glass vials and dried for 48 h at 40°C. Mosquitoes were weighed (±0.001 mg) in a Cahn electrobalance, then one wing of each mosquito glued onto a slide, and its length from the distal end of the alula to the tip, excluding the fringe scales, was measured with an ocular micrometer (±0.03 mm).

Metabolic reservoirs and blood meal uptake

Metabolic reserves were measured within 6 h of emergence. Glycogen and lipids were determined according to[1, 14, 15] and protein measured with the Bio-Rad Protein Quantitation Assay kit using Pierce’s bicinchoninic acid and bovine serum albumin as a standard[16]. For quantification of blood meal size, 5 day-old female mosquitoes were fed to repletion on a healthy, anaesthetised mouse, immobilised immediately on ice, and protein determined in individual midguts after dissection[17]. Means were compared by t-test[18] unless otherwise indicated.

Mosquito infections with Plasmodium

MF1 mice were infected with Plasmodium yoelii nigeriensis[19] by i.p. injection of 5 μL infected blood. Mice were checked microscopically on day 4 p.i. for the presence of parasites and exflagellating gametocytes. If exflagellations were observed, experimental mosquitoes were fed upon the anaesthetised mice.

Paired groups of approximately 30 3-day old females of low- and high-diet mosquitoes of the same species were fed simultaneously to repletion on one infected mouse. Fed mosquitoes were maintained as above for five days, cold-immobilised and midguts examined for oocysts after mercurochrome staining[20]. Prevalence is defined as the proportion of mosquitoes infected with Plasmodium; intensity of infection is defined as the geometric mean number of oocysts per mosquito.

Ovarian development

Mosquitoes of both diet regimens that had fully engorged on uninfected and Plasmodium-infected mice were dissected in physiological saline 3 days after the blood meal. Ovaries were examined at 400x magnification under a dissecting microscope. Development of ovaries was scored according to[21], and the number of developing eggs in each ovary, if applicable, was counted.

Statistical analysis

The effects of larval diet on adult body size and metabolic reserves were analysed with a Generalized Linear Model (GLM; Genstat, release 6.1). Two-sided t-probabilities were calculated to test pairwise differences between means. Effects were considered to be significant at p < 0.05. GLMs were also used to examine the effect of body size on bloodmeal uptake, and the effect of body size and Plasmodium infections on gonotrophic development. All possible two-way interactions were examined. The effect of body size on mosquito survival and on the proportion of oocyst-infected mosquitoes were analysed by GLM using a binomial distribution[20]. The number of oocysts per mosquito within a group were log-transformed and analysed as Poisson-distributed data, and GLM used to investigate the effect of body size on oocyst infections[18, 22].

Ethics statement

All animal work described in this paper was approved by the University of Aberdeen ethical review committee and was performed under an approved United Kingdom Home Office project licence (Licence Number PPL 60 2810).

No human subjects were asked to participate in this study and ethical clearance was not required. Although mosquitoes were fed upon a human arm, this was performed only by the first author as a standard routine method for mosquito maintenance.

Results

Wing length, dry weight and metabolic reserves

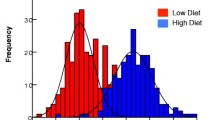

As the study focused on the blood meal uptake and Plasmodium infection, only female mosquitoes were analysed. The low and high larval diets produced significantly different size classes of mosquitoes (p < 0.001). Mean wing lengths for low and high diet An. gambiae were 2.77 ± 0.03 mm (n = 55) and 3.03 ± 0.02 mm (n = 48), and for An. stephensi were 2.66 ± 0.03 mm (n = 32) and 3.15 ± 0.02 mm (n = 35), respectively. The low diet An. gambiae (range 2.37-3.25 mm) included a number of individuals with dry weights and wing lengths comparable to those seen in the high-diet group (range 2.67-3.35 mm) and there was a poorer demarcation between low- and high-diet groups in this species (Figure 1).

Low-diet mosquitoes of both species had significantly less protein, lipid and glycogen upon emergence than high-diet individuals (p < 0.001) (Figure 2A-C). Corrected for dry body weight, the high-diet mosquitoes had proportionally significantly (p < 0.05 for all comparisons) more protein, lipid and glycogen reserves than the low-diet ones (Figure 2D). Blood ingestion per female increased significantly in high-diet mosquitoes (p < 0.001) from 0.344 to 0.405 mg protein /midgut in An. gambiae and from 0.359 to 0.548 mg protein/midgut in An. stephensi. While the increase in blood uptake between high- and low-diets groups was greater in An. stephensi than in An. gambiae, the relative increase was approximately 1.2-fold in both species (Figure 2E).

Effect in Anopheles gambiae (left) and Anopheles stephensi (right) of larval diet regime on total body reserves of protein (A) (n = 10 per treatment), lipid (B) (n = 30) and glycogen (C) (n = 10), on their relative proportion (D) upon emergence (means from A-C calculated as a proportion of dry weight, n = 28-48), and on blood meal size (E) (n = 10 except in low-diet An. gambiae , where n = 5). White background, low diet; grey background, high diet. In (D), vertical shading is glycogen, stippled shading is lipid and diagonal shading is protein. Error bars represent SEM.

Plasmodium infections and survival

We were able to obtain infection rates of P. y. nigeriensis much more comparable to those seen in the field for P. falciparum than usually reported in studies of murine malaria transmission[20, 23]. Only 24% of the low-diet An. gambiae given an infectious blood meal survived the 5 days until oocysts developed (Table 1). The mean oocyst prevalence of this group was 0.10 and the mean intensity ranged from 0 to 0.18 oocysts per mosquito. Of the high-diet An. gambiae, 75% survived 5 days after feeding. The mean oocyst prevalence was significantly higher (p < 0.001) at 0.49 and the mean intensities ranged from 0.59-0.87 oocysts per mosquito (p < 0.005 compared to low diet). Survival rates of low-diet An. gambiae were significantly lower than of the high-diet group (p < 0.001). There was no significant correlation of oocyst infections with body size but uninfected females were significantly smaller than mosquitoes infected with one (p = 0.01) or more (p = 0.001) oocysts (Figure 3A).

Mean survival rates of An. stephensi were ≥90% regardless of larval diet. Mean oocyst prevalence increased from 0.32 in the low-diet mosquitoes to 0.47 in the high-diet group and the intensity of infections similarly increased (Table 1). The oocyst intensities in An. stephensi were higher than in An. gambiae in both size classes. There was no difference in mean wing length of uninfected or infected An. stephensi (Figure 3B).

Plasmodium infections and gonotrophic development

Parasite infections had little effect on ovarian development in both mosquito species. High-diet, larger mosquitoes, both uninfected or infected, matured eggs more successfully than individuals raised on the low diet (p < 0.01), except in infected An. gambiae (Figure 4). Parasite infections had a greater effect on gonotrophic development in An. gambiae than in An. stephensi, as the proportion of infected female An. gambiae with reduced gonotrophic development (Christophers stages I-II) was larger than that of uninfected females (stage I: p = 008; stage II: p = 0.036). Plasmodium-infected, low-diet An. gambiae did not initiate oogenesis, while uninfected and infected rich-diet females were at similar stages of ovarian development 5 days after the infectious blood meal. In An. stephensi there was no effect of P. yoelii infection on ovarian development in both size classes (Figure 5).

Size of uninfected (white) and Plasmodium yoelii- infected (grey) Anopheles gambiae (A) and Anopheles stephensi (B) reaching different stages of ovarian development five days after feeding. Error bars represent SEM. ** - significant difference between uninfected and infected, p < 0.01. Mean size of uninfected An. gambiae at stage ≥ 4 was significantly greater than those at stages 1 (p < 0.001) and 3 (p = 0.008). Mean sizes of both groups of An. stephensi at stage ≥ 4 were significantly (p < 0.05) greater than stages 1 and 2.

Discussion

The nutritional status of larvae of An. gambiae and An. stephensi is manifested as differences in body size and reserves of protein, lipid and glycogen in teneral adults. Nutritionally-stressed An. gambiae emerge as small individuals that die within 48 h following emergence if deprived of a carbohydrate source[2, 24]. Well-fed individuals survive longer. Upon emergence, the fitness of mosquitoes is related directly to size, and in our study the quantity of larval food and not larval density caused these effects. Nutritionally-deprived larvae required 2–3 more days to reach pupation than the nutritionally well-fed siblings (data not shown). Both species responded in a similar fashion to the different larval diets, although in An. gambiae there was a gradient of adult size so that low-diet and high-diet size classes were not as distinct as those in An. stephensi. This may be because the more competitive larvae of An. gambiae were able to ingest more food to the detriment of their siblings or due to cannibalism[25]. Alternatively, at the larval density chosen for this study, density-dependent effects may already have been present in An. gambiae and not in An. stephensi[26]. Okech et al.[13] demonstrated the importance of nutrients from natural breeding sites on body size of An. gambiae. Although the nutrients used in their study were different from those in the present study, the data corroborate our findings about nutritionally-deprived mosquitoes.

Mosquito body size affects reproduction and survival, with larger mosquitoes producing more eggs during their lifetime than their smaller counterparts[1, 27, 28]. This is the case for both An. gambiae and An. stephensi as the gonotrophic development of the low-diet class of mosquitoes was much reduced compared with that of the high-diet class. The proportion of low-diet females entering a pre-gravid stage was greater than in the high-diet group, in which such a physiological condition was low or absent. Pre-gravid behaviour of wild An. gambiae is well documented[5, 12, 29], the proportion of adults in this condition varying seasonally, possibly depending on conditions in larval habitats. As we demonstrate in the present work, this may profoundly affect the ability of the mosquitoes to transmit malaria parasites. No such pre-gravid physiology was observed in An. stephensi.

Although we expected that the low diet would preferentially compromise lipid storage[1, 30], the deposition of protein, lipid and glycogen were all affected. Hence, low-diet mosquitoes not only started adult life as small individuals, but were also severely compromised nutritionally; this is manifested in a higher mortality rate in both laboratory[2, 24] and field[12] studies. The need for blood meals to aid adult nutrition rather than just reproduction is thus important. Additional protein required by small adults for survival must be derived from vertebrate blood, as the insects have limited protein reserves upon emergence[2, 31]. Conversely, nutritionally-rich larval diets are multiply beneficial; with increased body size and reserves, female mosquitoes not only live longer but ingest larger blood meals, complete ovarian development more successfully (this paper) and compete better for males[32, 33].

The biological interaction between nutritional status and Plasmodium infections is intriguing. In a large mosquito, uptake of a larger infectious blood meal will result in more parasites entering the mosquito midgut[34]. This could be harmful as higher death rates of large mosquitoes has been attributed to increased oocyst load that in turn competed for nutritional resources[35] or induction of a damaging immune response[36]. Our study is in agreement with the findings of Okech et al.[13] that body size affects the number of parasites that develop into oocysts. As a general rule, small mosquitoes developed fewer oocysts than their larger siblings. Although it is tempting to relate this observation to the smaller quantity of blood ingested by smaller females, this is clearly not the sole explanation. In An. stephensi, a 1.3-fold increase in blood meal size from low- to high-diet groups was accompanied by a similar 1.5-fold increase in prevalence and a modest 2.8-fold increase in mean oocyst intensity. Thus, in this species, differences in blood meal size probably account for all the differences in oocyst rates from the same infectious blood source. In stark contrast, the increase in blood meal size from low- to high-diet An. gambiae resulted in an approximately 5-fold increase in prevalence and 9-fold increase in mean intensity. Clearly the differences in blood meal size cannot alone account for the differences in oocyst infections.

Many more gametocytes are ingested during a blood meal than can be accounted for as oocysts[37, 38]. The likely candidates for modulating infections are components of the mosquito immune response[39–41]. Indeed, oxidative stress of the mosquito contributes greatly to the ‘infectious physiological background’ into which the gametocytes are placed during feeding[42, 43]. The dramatic differences in infection rates between low- and high-diet mosquitoes suggest that defensive mechanisms against ookinetes may be stimulated by the low diet, and when parasites are ingested by these mosquitoes, they either overload the already burdened stress responses to kill the mosquito or are killed by it. In contrast, large mosquitoes are less stressed upon emergence and consequently can maintain low-level infections without necessarily triggering the immune response or compromising their own survival. Such a model would favour the maintenance of highly responsive and biologically expensive immune genes in the population at low frequencies because while most of the small, stressed mosquitoes will die young, those that do survive may still contribute one or two batches of eggs to the population.

Our results suggest that parasites effected a greater mortality on the mosquitoes in nutritionally-compromised An. gambiae than in well-fed ones. In this group, although we did not study the mortality of uninfected mosquitoes, Lambrechts et al.[44] report a significant parasite-effected mortality in An. stephensi by P. yoelii. Similarly, Dawes et al.[9] report a density-dependent effect of P. berghei ookinetes in An. stephensi. Other reasons could be the small blood meal size or the absence of a critical factor for the oocyst. In a recent field study, investigating the effect of natural Plasmodium infections on wild An. gambiae and An. arabiensis, mosquitoes with larger body size produced more eggs but sporozoite infection did not affect egg production, which corroborates our findings[45]. As with our study, small-sized individuals may not have been noticed as they died early in the infection process possibly due to reduced fitness[35]. From this we conclude that mosquito fitness contributed to the higher survival rate of well-fed An. gambiae. Plasmodium yoelii nigeriensis had only a small effect on An. stephensi of both size classes, which may be attributed to the relatively low oocyst load of infected mosquitoes.

Parasite infections had only a negligible effect on the gonotrophic development in both species, in contrast to previous demonstrations of P. y. nigeriensis negatively affecting fecundity of An. stephensi[19, 44, 46]. However, occyst intensities in the present study were <1, whereas much greater oocyst burdens were used previously. It is therefore possible that oocyst load directly affects mosquito fitness and that the densities observed in our study were below the threshold for negative effects to occur. The above-mentioned studies added para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) to sugar water as an extra nutritional source following a Plasmodium-infected blood meal. PABA may have affected the infectiousness of the parasites, leading to relatively high oocyst intensities, which are unusual in wild mosquitoes[20, 23]. Natural densities of P. falciparum oocysts typically average 0.25-3 oocysts per mosquito (range = 0–60)[20, 47–49] and this strong skew in favour of no infections and low densities may serve as a natural mechanism or trade-off, regulating mosquito fitness in response to Plasmodium. With low oocyst densities there was no effect of P. y. nigeriensis on ovarian development in An. stephensi; body size was the only factor determining fecundity. Hopwood et al.[50] reported significant apoptosis and ovarian resorption in An. stephensi as a result of Plasmodium infection. We did not observe negative effects of parasite infections on ovarian development, possibly because the oocyst intensities were lower or because we had not added antibiotics and para-aminobenzoic acid to the adult sugar source. In An. gambiae the parasites affected the small-sized mosquitoes: mortality of infected mosquitoes increased and ovarian development was stopped. However, because so few low-diet mosquitoes survived the oocyst incubation time (n = 4), the results are equivocal and further examination is required. Gonotrophic development of large females of An. gambiae was unaffected by parasite infections. It is possible that in previous studies the combination of large-sized mosquitoes and high parasite densities may have obscured any influence of diet, environment or parasite on mosquito fitness[51].

These studies emphasise the important differences in the physiological adaptations to nutritional stress of two closely-related mosquito species. Under identical conditions, both species respond to dietary quantity and availability by altering their body size and nutrional reserves. However, while An. gambiae fitness is severely compromised by the low-diet, small and large An. stephensi are of comparable fitness in the short period of study. The reasons for this are unknown, but may result from the disproportionately poor lipid storage in small An. gambiae, conferring poor fitness.

The low infection rates and low impact of the parasite on high-diet mosquitoes may more closely reflect natural interactions between malaria and mosquitoes. Mosquito fitness is regulated in the larval stages by density dependence and environment[12], and in the adult stages by climate and the availability of blood sources, carbohydrate resources and oviposition sites[2, 52, 53]. Parasite infections may have important fitness consequences for the vector[7, 54], and the scale of these consequences will be controlled by the vector and parasite interaction. The evolutionary co-adaptation of parasite and vector will eventually determine the success of transmission, and from our results it appears that a propensity for low parasite infections may be the best adaptive strategy for this interaction.

Conclusions

The nutritional status of An. gambiae and An. stephensi upon emergence had different outcomes upon Plasmodium infections. Nutritionally-compromised females of An. gambiae died early in adult life, had a lower prevalence of Plasmodium infection and developed significantly fewer oocysts than well-fed females. In contrast, the nutritional status of An. stephensi had no effect on survival over the period of study nor on Plasmodium development. In both mosquito species poor nutrition but not Plasmodium infection inhibited ovarian development.

References

Briegel H: Fecundity, metabolism, and body size in Anopheles (Diptera: Culicidae), Vectors of Malaria. J Med Entomol. 1990, 27: 839-850.

Takken W, Klowden MJ, Chambers GM: Effect of body size on host seeking and blood meal utilization in Anopheles gambiae sensu stricto (Diptera: Culicidae): the disadvantage of being small. J Med Entomol. 1998, 35: 639-645.

Ng’habi KR, Huho BJ, Nkwengulila G, Killeen GF, Knols BGJ, Ferguson HM: Sexual selection in mosquito swarms: may the best man lose?. Anim Behav. 2008, 76: 105-112. 10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.01.014.

Hurd H: Interactions between parasites and insects vectors. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1994, 89 (Suppl 2): 27-30.

Gillies MT: The recognition of age-groups within populations of Anopheles gambiae by the pre-gravid rate and the sporozoite rate. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1954, 48: 58-74.

Gillies MT: The pre-gravid phase of ovarian development in Anopheles funestus. Ann Trop Med Parasit. 1955, 49: 320-325.

Hurd H: Manipulation of medically important insect vectors by their parasites. Annu Rev Entomol. 2003, 48: 141-161. 10.1146/annurev.ento.48.091801.112722.

Rivero A, Ferguson HM: The energetic budget of Anopheles stephensi infected with Plasmodium chabaudi: is energy depletion a mechanism for virulence?. Proc R Soc Lond Ser B-Biol Sci. 2003, 270: 1365-1371. 10.1098/rspb.2003.2389.

Dawes EJ, Churcher TS, Zhuang S, Sinden RE, Basáñez MF: Anopheles mortality is both age- and Plasmodium-density dependent: implications for malaria transmission. Malar J. 2009, 8: 228-10.1186/1475-2875-8-228.

Hurd H, Hogg JC, Renshaw M: Interactions between bloodfeeding, fecundity and infection in mosquitoes. Parasitol Today. 1995, 11: 411-416. 10.1016/0169-4758(95)80021-2.

Hogg JC, Carwardine S, Hurd H: The effect of Plasmodium yoelii nigeriensis infection on ovarian protein accumulation by Anopheles stephensi. Parasitol Res. 1997, 83: 374-379.

Lyimo EO, Takken W: Effects of adult body size on fecundity and the pregravid rate of Anopheles gambiae females in Tanzania. Med Vet Entomol. 1993, 7: 328-332. 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1993.tb00700.x.

Okech BA, Gouagna LC, Yan G, Githure JI, Beier JC: Larval habitats of Anopheles gambiae s.s. (Diptera: Culicidae) influences vector competence to Plasmodium falciparum parasites. Malar J. 2007, 6: 50-10.1186/1475-2875-6-50.

Van Händel E: Rapid determination of glycogen and sugars in mosquitoes. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1985, 1: 299-301.

Van Händel E: Rapid determination of total lipids in mosquitoes. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1985, 1: 302-304.

Billingsley PF, Hecker H: Blood digestion in the mosquito, Anopheles stephensi Liston (Diptera: Culicidae): activity and distribution of trypsin, aminopeptidase, and alpha-glucosidase in the midgut. J Med Entomol. 1991, 28: 865-871.

Billingsley PF, Hodivala KJ, Winger LA, Sinden RE: Detection of mature malaria infections in live mosquitoes. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1991, 85: 450-453. 10.1016/0035-9203(91)90215-K.

Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ: Biometry: the Principles and the Practice of Statistics in Biological Research. 1998, New York: WH Freeman and Company, 3

Hogg JC, Hurd H: Malaria-induced reduction of fecundity during the first gonotrophic cycle of Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes. Med Vet Entomol. 1995, 9: 176-180. 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1995.tb00175.x.

Billingsley PF, Medley GF, Charlwood D, Sinden RE: Relationship between prevalence and intensity of Plasmodium falciparum infection in natural populations of Anopheles mosquitos. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994, 51: 260-270.

Christophers SR: The development of the egg follicle in anophelines. Paludism. 1911, 2: 73-78.

Oude Voshaar JH: Statistiek voor Onderzoekers. Met voorbeelden uit de Landbouw en Milieuwetenschappen. 1994, The Netherlands: Wageningen Pers, Wageningen

Medley GF, Sinden RE, Fleck S, Billingsley PF, Tirawanchai N, Rodriguez MH: Heterogeneity in patterns of malarial oocyst infections in the mosquito vector. Parasitology. 1993, 106: 441-449. 10.1017/S0031182000076721.

Foster WA, Takken W: Nectar-related vs. human-related volatiles: behavioural response and choice by female and male Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) between emergence and first feeding. Bull Entomol Res. 2004, 94: 145-157. 10.1079/BER2003288.

Koenraadt CJM, Takken W: Cannibalism and predation among larvae of the Anopheles gambiae complex. Med Vet Entomol. 2003, 17: 61-66. 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2003.00409.x.

Lyimo EO, Takken W, Koella JC: Effect of rearing temperature and larval density on larval survival, age at pupation and adult size of Anopheles gambiae. Entomol Exp Appl. 1992, 63: 265-271. 10.1111/j.1570-7458.1992.tb01583.x.

Steinwascher K: Relationship between pupal mass and adult survivorship and fecundity for Aedes aegypti. Environ Entomol. 1982, 11: 150-153.

Packer MJ, Corbet P: Size variation and reproductive success of female Aedes punctor (Diptera: Culicidae). Ecol Entomol. 1989, 14: 297-309. 10.1111/j.1365-2311.1989.tb00960.x.

Charlwood JD, Smith T, Billingsley FF, Takken W, Lyimo EOK, Meuwissen JHET: Survival and infection probabilities of anthropophagie anophelines from an area of high prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum in humans. Bull Entomol Res. 1997, 87: 445-453. 10.1017/S0007485300041304.

Briegel H: Physiological bases of mosquito ecology. J Vector Ecol. 2003, 28: 1-11.

Harrington LC, Edman JD, Scott TW: Why do female Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) feed preferentially and frequently on human blood?. J Med Entomol. 2001, 38: 411-422. 10.1603/0022-2585-38.3.411.

Okanda FM, Dao A, Njiru BN, Arija J, Akelo HA, Toure Y, Odulaja A, Beier JC, Githure JI, Yan G: Behavioural determinants of gene flow in malaria vector populations: Anopheles gambiae males select large females as mates. Malar J. 2002, 1: 10-10.1186/1475-2875-1-10.

Ponlawat A, Harrington LC: Factors associated with male mating success of the dengue vector mosquito, Aedes aegypti. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009, 80: 395-400.

Pichon G, Awono-Ambene HP, Robert V: High heterogeneity in the number of Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes in the bloodmeal of mosquitoes fed on the same host. Parasitology. 2000, 121: 115-120. 10.1017/S0031182099006277.

Lyimo EO, Koella JC: Relationship between body size of adult Anopheles gambiae s.l. and infection with malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitology. 1992, 104: 233-237. 10.1017/S0031182000061667.

Barillas Mury C, Kumar S: Plasmodium-mosquito interactions: a tale of dangerous liaisons. Cell Microbiol. 2005, 7: 1539-1545. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00615.x.

Alavi Y, Arai M, Mendoza J, Tufet-Bayona M, Sinha R, Fowler K, Billker O, Franke-Fayard B, Janse CJ, Waters A: The dynamics of interactions between Plasmodium and the mosquito: a study of the infectivity of Plasmodium berghei and Plasmodium gallinaceum, and their transmission by Anopheles stephensi, Anopheles gambiae and Aedes aegypti. Int J Parasit. 2003, 33: 933-943. 10.1016/S0020-7519(03)00112-7.

Alavi Y, Arai M, Mendoza J, Tufet-Bayona M, Sinha R, Fowler K, Billker O, Franke-Fayard B, Janse CJ, Waters A: Corrigendum to: the dynamics of interactions between Plasmodium and the mosquito: a study of the infectivity of Plasmodium berghei and Plasmodium gallinaceum, and their transmission by Anopheles stephensi, Anopheles gambiae and Aedes aegypti (vol 33, pg 933, 2003). Int J Parasit. 2004, 34: 245-247. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2003.05.001.

Cirimotich CM, Dong Y, Garver LS, Sim S, Dimopoulos G: Mosquito immune defenses against Plasmodium infection. Dev Comp Immunol. 2010, 34: 387-395. 10.1016/j.dci.2009.12.005.

Dimopoulos G, Muller HM, Levashina EA, Kafatos FC: Innate immune defense against malaria infection in the mosquito. Curr Opin Immunol. 2001, 13: 79-88. 10.1016/S0952-7915(00)00186-2.

Mendes AM, Schlegelmilch T, Cohuet A, Awono-Ambene P, De Iorio M, Fontenille D, Morlais I, Christophides GK, Kafatos FC, Vlachou D: Conserved mosquito/parasite interactions affect development of Plasmodium falciparum in Africa. PLoS Path. 2008, 4: e1000069-10.1371/journal.ppat.1000069.

Christophides GK, Zdobnov E, Barillas-Mury C, Birney E, Blandin S, Blass C, Brey PT, Collins FH, Danielli A, Dimopoulos G: Immunity-related genes and gene families in Anopheles gambiae. Science. 2002, 298: 159-165. 10.1126/science.1077136.

Drexler AL, Vodovotz Y, Luckhart S: Plasmodium development in the mosquito: biology bottlenecks and opportunities for mathematical modeling. Trends Parasitol. 2008, 24: 333-336. 10.1016/j.pt.2008.05.005.

Lambrechts L, Chavatte JM, Snounou G, Koella JC: Environmental influence on the genetic basis of mosquito resistance to malaria parasites. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci. 2006, 273: 1501-1506. 10.1098/rspb.2006.3483.

Yaro AS, Toure AM, Guindo A, Coulibaly MB, Dao A, Diallo M, Traore SF: Reproductive success in Anopheles arabiensis and the M and S molecular forms of Anopheles gambiae: do natural sporozoite infection and body size matter?. Acta Trop. 2012, 122: 87-93. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.12.005.

Ahmed AM, Maingon RD, Taylor PJ, Hurd H: The effects of infection with Plasmodium yoelii nigeriensis on the reproductive fitness of the mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Invertebr Reprod Dev. 1999, 36: 217-222. 10.1080/07924259.1999.9652703.

Taylor LH: Infection rates in, and the number of Plasmodium falciparum genotypes carried by Anopheles mosquitoes in Tanzania. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1999, 93: 659-662. 10.1080/00034989958168.

Pringle G: A quantitative study of naturally-acquired malaria infections in Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles funestus in a highly malarious area of East Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1966, 60: 626-632. 10.1016/0035-9203(66)90009-5.

Haji H, Smith T, Charlwood JD, Meuwissen JH: Absence of relationships between selected human factors and natural infectivity of Plasmodium falciparum to mosquitoes in an area of high transmission. Parasitology. 1996, 113: 425-431. 10.1017/S0031182000081488.

Hopwood JA, Ahmed AM, Polwart A, Williams GT, Hurd H: Malaria-induced apoptosis in mosquito ovaries: a mechanism to control vector egg production. J Exp Biol. 2001, 204: 2773-2780.

Ferguson HM, Read AF: Why is the effect of malaria parasites on mosquito survival still unresolved?. Trends Parasitol. 2002, 18: 256-260. 10.1016/S1471-4922(02)02281-X.

Straif SC, Beier JC: Effects of sugar availability on the blood-feeding behavior of Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. 1996, 33: 608-612.

Okech BA, Gouagna LC, Killeen GF, Knols BG, Kabiru EW, Beier JC, Yan G, Githure JI: Influence of sugar availability and indoor microclimate on survival of Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) under semifield conditions in western Kenya. J Med Entomol. 2003, 40: 657-663. 10.1603/0022-2585-40.5.657.

Anderson RA, Knols BG, Koella JC: Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites increase feeding-associated mortality of their mosquito hosts Anopheles gambiae s.l. Parasitology. 2000, 120: 329-333. 10.1017/S0031182099005570.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kevin McKenzie for assistance with wing length measurements and Louise Swan for dissections and other laboratory assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: WT PFB JM-L. Performed the experiments: WT AJV VJ MB. Analyzed data: WT RCS PFB. Wrote the paper: WT and PFB. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Takken, W., Smallegange, R.C., Vigneau, A.J. et al. Larval nutrition differentially affects adult fitness and Plasmodium development in the malaria vectors Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles stephensi. Parasites Vectors 6, 345 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-6-345

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-6-345