Abstract

Background

High grade serous ovarian cancer is one of the poorly characterized malignancies. This study aimed to elucidate the mutational events in Malaysian patients with high grade serous ovarian cancer by performing targeted sequencing on 50 cancer hotspot genes.

Results

Nine high grade serous ovarian carcinoma samples and ten normal ovarian tissues were obtained from Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Center (UKMMC) and the Kajang Hospital. The Ion AmpliSeq™ Cancer Hotspot Panel v2 targeting “mutation-hotspot region” in 50 most common cancer-associated genes was utilized. A total of 20 variants were identified in 12 genes. Eleven (55%) were silent alterations and nine (45%) were missense mutations. Six of the nine missense mutations were predicted to be deleterious while the other three have low or neutral protein impact. Eight genes were altered in both the tumor and normal groups (APC, EGFR, FGFR3, KDR, MET, PDGFRA, RET and SMO) while four genes (TP53, PIK3CA, STK11 and KIT) were exclusively altered in the tumor group. TP53 alterations were present in all the tumors but not in the normal group. Six deleterious mutations in TP53 (p.R175H, p.H193R, p.Y220C, p.Y163C, p.R282G and p.Y234H) were identified in eight serous ovarian carcinoma samples and none in the normal group.

Conclusion

TP53 remains as the most frequently altered gene in high grade serous ovarian cancer and Ion Torrent Personal Genome Machine (PGM) in combination with Ion Ampliseq™ Cancer Hotspot Panel v2 were proven to be instrumental in identifying a wide range of genetic alterations simultaneously from a minute amount of DNA. However, larger series of validation targeting more genes are necessary in order to shed a light on the molecular events underlying pathogenesis of this cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Detecting cancer at an early stage or tackling it at the late stage in an efficient way is always a challenge in clinical care. Molecular approaches are now used widely at many stages of cancer management and continue to expand with the increase in the understanding of cancer biology and the correlation between genotype and phenotype. Cancer treatment has been revolutionised by the demand in molecular diagnostics to detect standard-of-care mutations with druggable targets and to predict drug response and survival [1]. The next generation sequencing (NGS) approach has become a powerful platform to complement clinical diagnosis and assist in therapeutic decision-making in cancer due to its improved sensitivity in mutation detection and fast-turnaround time compared to current gold standard methods. It has also the ability to simultaneously sequence multiple cancer-driving genes in a single assay [1].

The Sanger sequencing method, introduced in 1970, has been the gold standard for mutation analysis in cancer diagnostics [2]. However, it has a relatively low sensitivity, lower throughput with higher turnaround time and overall cost [3]. The emergence of NGS, three decades later, has overcome these drawbacks via its ability to massively sequence millions of DNA segments in parallel hence lowering the cost of sequencing per base and achieve a faster turnaround time and superior sensitivity in mutation detection [3]. As of now, whole genome sequencing is still too expensive to be used for routine diagnostics hence the option to perform targeted sequencing of exon coding regions or a subset of genes of interest offered by NGS is an attractive approach [4]. In comparison with the single gene analysis which is commonly done with the Sanger approach, the application of NGS in cancer diagnostics allows the analysis of multiple genes to identify druggable mutations and also to generate a more complete genotype of the cancer.

This study focused on ovarian cancer which is the fourth most frequently diagnosed cancer among Malaysian women, with 656 cases reported in 2007 [5]. Globally, this devastating disease is the third most common gynecological malignancy with around 225,000 new cases diagnosed in 2008 and 46.7% of them contributed by the Asian population [6]. Ovarian cancer consists of a heterogeneous group of tumors with distinct histological features, molecular characteristics and clinical behavior [7, 8]. The most common subtype of epithelial ovarian cancers is the serous carcinoma [9]. Malpica and colleagues described a 2-tier system for grading serous ovarian carcinoma i.e. as a high grade (formerly grade 2 and 3 tumors) or low grade (formerly grade 1), based mainly on the degree of nuclear atypia and mitotic rate [10]. This grading system has resulted in an effective classification of serous ovarian carcinoma as it has been proven that the low and high grade serous ovarian cancers are not only histologically different, but also exhibit distinct molecular, epidemiologic and clinical features [11].

Low grade serous ovarian carcinoma patients are younger than those with high grade counterpart, with age range from 45–57 year old and 55–65 year old, respectively [10]. In a study that compared consequence between both types of serous ovarian carcinomas using the 2-tier system, patients with low grade tumors have better survival and mortality due to disease was more rapid with high grade tumors [10]. With high grade tumors, the median survival was 1.7 years compared to 4.2 years for patients with low grade tumors [10].

From genetic perspectives, the low grade serous ovarian carcinoma is characterized by mutations in KRAS, BRAF or ERBB2 genes; whereby approximately 66% of cases have mutations in at least one of these genes with the ERBB2 being the least frequently mutated [12–14]. Mutual exclusivity is observed in these three genes; a tumor with a KRAS mutation will not have a mutation of the other two genes, and vice versa[9]. Comparatively, less is known about the pathogenesis of high grade serous carcinoma. Mutations of KRAS, BRAF, or ERBB2 are infrequently detected in high grade carcinoma [12–14]. On the contrary, 80% of high grade tumors harbor TP53 mutation and various DNA copy number aberrations [15–17]. In addition, a specific KRAS mutation found in low grade serous ovarian cancer has been shown to be associated with shorter survival, further adding a clinical value of NGS in cancer research [18]. Thus it is pertinent to improve our understanding of the high grade serous ovarian cancer in order to predict the prognosis of patients or for making therapeutic decisions. This study was undertaken to characterize the gene alterations in high grade serous ovarian cancer in Malaysian patients by performing targeted sequencing on 50 cancer genes with established biological functions in cancer.

Methods

Clinical specimens

Nine high grade serous ovarian carcinoma samples were obtained from newly diagnosed patients undergoing total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salphingo-oophorectomy (TAHBSO) at the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Center (UKMMC) and the Kajang Hospital. Ten normal ovarian tissues were also obtained from patients undergoing TAHBSO for benign gynecological diseases. The study was approved by the UKM Medical Research Ethics Committee and written informed consent was taken from the participants. None of patients had received chemotherapy or radiotherapy. The tissues were kept frozen in liquid nitrogen until subjected to cryosectioning. Hematoxylin & Eosin staining (H&E) was performed and the slides were reviewed by the pathologist. Only tissue sections that contained more than 80% tumor cell nuclei with less than 20% necrosis were included in this study. The normal specimens were confirmed to be free from tumor or inflammatory cells.

DNA extraction and quality assessments

DNA was extracted from the tissues using the DNAeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Nucleic acid quality and quantity were assessed using the Qubit Fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE) and agarose gel electrophoresis. The highly intact and non-degraded RNA-free genomic DNA was subjected to library preparation prior to sequencing. We used 10 ng of DNA of each sample for the Ion Ampliseq library preparation.

Library preparation

We used the Ion AmpliSeq™ Cancer Hotspot Panel v2 (Life Technologies, Guilford, CT) which allows the characterization of mutational hotspots in 50 cancer-related genes (Additional file 1: Table S1). Library preparation was performed using the Ion Ampliseq Library Kits 2.0 protocol. DNA amplification was carried out using the Ion AmpliSeq Cancer Hotspot Panel v2 and the 5x Ion AmpliseqHiFi Master Mix. Sequencing adaptors with short stretches of index sequences (barcodes) that enable sample multiplexing were ligated to the amplicons using the Ion Express Barcode Adaptors Kit (Life Technologies, Guilford, CT). The adapters-ligated amplicons (library) were purified using the Agencourt AMPure XP reagent (BD Biosciences, USA). The library was subjected to the second round of amplification using the Platinum PCR SuperMix High Fidelity and Library Amplification Primer Mix. The amplified library underwent three rounds of purification using the Agencourt AMPure XP reagent. The library was then quantified using the Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity DNA chip (Agilent Technologies Inc, Santa Clara, CA). The desired concentration for template preparation on the One Touch instrument was between 15 to 20 pM.

Emulsion PCR and ion torrent PGM™ sequencing

The clonal amplification of the barcoded DNA library onto the ion spheres (ISPs) was carried out using emulsion PCR and the subsequent isolation of ISPs with DNA was performed using Ion OneTouch 200 Template Kit v2 DL and Ion OneTouch ES (Life Technologies, Guilford, CT) as described by the manufacturer. The polyclonal percentage and quality of the enriched, template-positive ISPs was determined using the Ion Sphere Quality Control Kit (Life Technologies, Guilford, CT). Samples with polyclonal percentage of less than 30% and enriched, template-positive ISPs of more than >80% were subjected for sequencing on the Ion Torrent Personal Genome Machine (PGM™). Enriched ISPs were subjected to sequencing on a 314 v2 Ion Chip (two samples per chip) using Ion PGM™ Sequencing 200 kit v2 (Life Technologies, Guilford, CT). A cut-off with a quality score of Q17 (a quality score of 2% errors, corresponding to 1 base error allowed per 50 bases) was used as a measure of successful sequencing.

Validation using sanger sequencing

Variants identified were validated using the Sanger sequencing method. Primers corresponding to the alteration sites were purchased from Life Technologies. The primer pairs chosen are HS00424883_CE, HS00432201_CE and HS00346578_CE. Briefly, PCR products were generated and cycle sequencing was performed using the Big Dye Terminator V3.1 reagent (Life Technologies, Guilford, CT). The cycle sequencing products were then processed using ethanol precipitation and sequencing was carried out using the ABI 3130xl capillary electrophoresis (Life Technologies, Guilford, CT). The results were analyzed using the Basic Local Alignment System Tool (BLAST).

Bioinformatics analysis

Read mapping and variants calling

Data from sequencing runs from Ion Torrent PGM™ were automatically transferred to the Torrent Server hosting the Torrent Suite Software that processed the raw voltage semiconductor sequencing data into DNA base calls. The Torrent Suite Software utilizes the Torrent Browser that includes TMAP alignment and Torrent Variant Caller for alignment and variant detection. Data were aligned against Human hg19 database. The Ion Reporter Software (Life Technologies, Guilford, CT) was used to perform variant calling and mapping.

Filtering of the variants called

A number of steps were used to filter nucleotide variants identified in the screening; (a) variants that are not annotated as pathogenic or probable pathogenic variants were excluded, (b) variants called in both normal and serous ovarian cancer genome were excluded and (c) variants representing probable mapping ambiguities were excluded. Manual and thorough observation of the variants using the Integrated Genomic Viewer (IGV) was performed to exclude false variants [19].

Predicting the functional significance of nonsynonymous mutations

Nonsynonymous missense mutations called were evaluated by in silico analysis using the TransFIC (TRANSformed Functional Impact for Cancer (TransFIC) method (http://bg.upf.edu/transfic/). The method transforms Functional Impact scores taking into account the differences in basal tolerance to germline structural number variations of genes that belongs to the different functional classes. This transformation allows the use of the scores provided by well-known tools (SIFT, Polyphen2 and Mutation Assessor) to rank the functional impact of cancer somatic mutations. Mutations with a greater TransFIC values are more likely to be the cancer drivers.

Cancer genes annotation

Annotation was performed using Oncotator (http://www.broadinstitute.org/oncotator/), a web application for annotating human genomic point mutations and indels with data relevant to cancer researchers.

Statistical analysis

We utilized the Fisher's exact test to define significant values in a number of altered genes and total variants between tumor and normal samples using the 2 × 2 contingency tables and the GraphPad QuickCalcs Online Calculator for Scientists (http://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/index.cfm). All p values are two-sided and statistical significance is denoted by p <0.05.

Integrative analysis using the ICGC data portal

We used the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) Data Portal [20], a web tool for exploring, visualizing and analyzing multi-dimensional cancer genomics data, to interactively explore genetic alterations across samples, genes and pathways in both the ICGC and our datasets.

Results

Epidemiological characteristics

The epidemiological features of the studied subjects are presented in Table 1. The median age was 57 years for the patients with serous ovarian cancer and 52 years for the normal controls.

Technical performance of the Ion AmpliSeq™ Cancer Hotspot Panel v2

The Ion AmpliSeq™ Cancer Hotspot Panel v2 contains 207 primer pairs that cover the “mutation-hotspot region” in 50 most common cancer-associated genes (Additional file 1: Table S1). The average sample loading obtained was 83.8% (range 76% - 91%). The total reads ranged from 220,000 – 420,000 reads with an average read length of 112 bp. The details on the loading percentage, number of reads and sequenced bases for each of the samples are summarized in Additional file 1: Table S2. On average, the sequencing coverage for each of the regions is >1000×.

Summary of identified variants

We identified a total of 20 variants in 12 genes. Eight genes were altered in both the tumor and normal groups (APC, EGFR, FGFR3, KDR, MET, PDGFRA, RET and SMO) while four genes (TP53, PIK3CA, STK11 and KIT) showed presence of alterations in only the cancer samples. From the total of 20 variants, 11 (55%) were silent alterations and nine (45%) were missense mutations. Six of the nine missense mutations were predicted to have deleterious impact on the proteins while the other three have low or neutral protein impact. Ten variants were identified from eight genes in both the tumor and normal groups (APC, EGFR, FGFR3, KDR, MET, PDGFRA, RET and SMO). However upon annotation, these variants resulted in no amino acid changes (silent alteration), have neutral protein impact or presented in normal population according to dbSNP database version 38 (minimal allele frequency >2%).

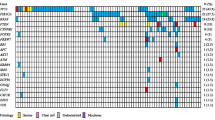

Base transitions (purine-purine and pyrimide-pyrimidine) were more frequent than transversions (purine-pyrimidine, vice versa) (Additional file 1: Figure S1). At least four genes were altered in each tumor and normal samples. The details on the variant frequency are shown in Table 2. Our results showed that TP53 alterations were present in all the tumors but not in the normal group. We further analyzed the types of alteration identified in the high grade serous ovarian cancer. Table 3 illustrates the variant distribution of the high grade serous ovarian carcinoma in our cohort of patients. After manual filtration, eight of the nine high grade serous ovarian carcinoma samples harboured one deleterious mutation and all of the deleterious mutations were found in TP53 as shown in Table 4. The remaining one high grade serous ovarian carcinoma sample (T7) did not have any deleterious mutation. There was no deleterious mutation found in the 10 normal samples (Additional file 1: Table S3). In addition, the cancer samples showed significantly more altered genes than the normal group (average seven altered genes in tumor group versus 4.8 altered genes in normal group; p value = 0.0001). Six deleterious mutations in TP53 with different codon and protein changes were identified in eight serous ovarian carcinoma samples (Figure 1).

Deleterious mutations identified by targeted next generation sequencing in serous ovarian carcinoma. Representation of the reads aligned to the reference genome of A) Tumor 1; B) Tumor 2; C) Tumor 3; D) Tumor 4; E) Tumor 5; F) Tumor 6; G) Tumor 8 and H) Tumor 9; as provided by the Integrative Genomics Viewer V 2.3 software [19].

Correlation with ICGC datasets

We compared the deleterious mutations obtained from this study with those in the ICGC Data Portal. Table 5 illustrates the correlations and occurrences of those deleterious mutations. Among all of the deleterious mutations found in this study, four have been reported in serous ovarian carcinoma from the consortium (TP53 p.R175H, p.H193R, p.Y220C, p.Y163C and p.R282G) with the frequency ranging from 0.36 - 2.16% [20]. Meanwhile, the TP53 p.R282G and p.Y234H have not been reported to be present in the ICGC’s serous ovarian carcinoma cases but have been detected in lung cancer (0.9%), breast cancer (0.11%) and renal cancer (0.25%) [20].

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed the base alteration status of 50 cancer-related genes using a targeted NGS approach on nine high grade serous ovarian carcinoma and 10 normal ovaries. Since all cancers included in our study were of high grade serous histology, we have avoided any false correlation that might have resulted from a study of mixed histological types. We observed that transitions and substitutions were more frequent than transversions and this is in agreement with other studies on the patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes [21, 22].

We found that TP53 alterations were the most common alterations identified in our local patients with high grade serous ovarian carcinoma. In addition, the majority of alterations identified in TP53 were predicted to be deleterious and four of the mutations were the hotspot mutations (p.R175H, p.H193R, p.Y220C and p.Y163C). These deleterious mutations in TP53 were detected in eight of the nine cancer samples. Our findings were in agreement with other studies on high grade serous ovarian carcinoma in which more than 80% of cases harboured TP53 mutations [12, 15, 17]. We could conclude that TP53 mutations remain the most consistent genomic feature in high grade serous ovarian carcinoma.

TP53 which encodes the tumor suppressor protein p53, is among the most frequently mutated genes in human cancers [23]. The ubiquitous presence of TP53 mutations in ovarian cancer has been suggested more than 20 years ago, particularly in those with serous histology [24]. Whilst some tumor suppressor genes, such as APC or BRCA1, are frequently deactivated by the frame shift or nonsense mutations, the missense mutation is the predominant type of mutation in TP53 in human tumors [25]. These mutations are identified mainly in exons 4–9, which encode the DNA-binding domain of the protein [26]. We identified seven mutations in TP53 DNA binding domain from which six were missense mutations (86%) and one silent alteration (14%). These observations confirmed previous findings that missense mutation was the predominant alteration in TP53 in tumors [25].

A tumor cell with a TP53 missense mutation could result in full-length p53 proteins which have prolonged half-life and tend to accumulate in the tumor cells [25]. These mutant proteins were hypothesized to possess the ability to influence tumor progression. Oren and Rotter revealed that mutant p53 proteins can bind and deactivate other related proteins such as p63 and p73 [27]. This tumorigenic activity of mutant p53 has been described as gain-of-function (GOF), which was shown to coerce tumor cells toward migration, invasion and metastasis in mouse models as demonstrated by several other studies [28, 29]. A study by Kang and colleagues also demonstrated that high grade serous ovarian cancer patients with GOF mutant p53 frequently showed resistance against platinum-based treatment and were prone to distant metastasis [25].

We also observed low impact alteration in KIT and STK11 exclusively in the tumor group which resulted from base transversions. The KIT p.K546K, a silent alteration resulted from A > G transversion at position 55593481, was identified in sample T1 and was not detected in any ICGC studies [20]. Another alteration in KIT, the p.M541L, is a missense mutation resulting from A > C transversion at position 55593464 found in sample T4, was also detected in a patient with gastric cancer patient as reported in the ICGC’s portal [20]. The STK11 p.F354L, a missense mutation identified in sample T4 and T6, resulted from a C > G transversion at position 1223125. To our knowledge, this alteration has not been detected in any of the published data from the consortium studies. The significance of these low impact alterations is still yet to be identified. However, the effort towards the development of personalized medicine must be guided by a comprehensive look at the mutational landscape of each tumor, hence these low impact alterations should not be disregarded.

The small sample size is an obvious limitation of this study and this could affect our interpretation of the results. Therefore a larger series of validation including bigger sample size, different histological subtypes, inclusion of germline DNA derived from the same sample are indispensable in order to fully understand the genetic events underlying this cancer. In addition, this panel is targeting “hotspot” region of genes that are frequently mutated in human cancer thus other infrequently altered genes but of significance to serous ovarian cancers might have been excluded such as ARID1A, BRCA1, BRCA2, CSMD3, NF1, CDK12, FAT3 and GABRA6[30]. Furthermore, variation in cancers may not be reflected in the sequence variation alone. Other important factors such as gene expression (coding and non-coding), DNA methylation as well as influence of genomic rearrangements such as copy number and structural variations are unable to be reliably addressed using this approach.

Conclusions

Our findings revealed a relatively small number of somatic alterations in high grade serous ovarian cancer using this commercially available cancer hotspot panel. An extensive somatic mutation screening targeting more genes using the Ion Ampliseq™ Comprehensive Cancer Panel (CCP) or whole exome sequencing might be a preferred approach for future research, particularly in this disease. Undoubtedly, the implementation of this hotspot panel in routine molecular diagnostics for high grade serous ovarian carcinoma definitely requires validation in larger series of samples. Nevertheless, its superior performance in identifying a wide range of genetic alterations simultaneously from a minute amount of DNA can facilitate the evaluation of tumor-specific treatment susceptibility and individual prognosis.

References

McCourt CM, McArt DG, Mills K, Catherwood MA, Maxwell P, Waugh DJ, Hamilton P, O'Sullivan JM, Salto-Tellez M: Validation of next generation sequencing technologies in comparison to current diagnostic gold standards for BRAF. EGFR and KRAS mutational analysis. PLoS One. 2013, 8: e69604-10.1371/journal.pone.0069604.

Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson AR: DNA sequencing with chain terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977, 74: 5463-5467. 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463.

Meldrum C, Doyle MA, Tothill RW: Next-generation sequencing for cancer diagnostics: A practical perspective. Clin Biochem Rev. 2011, 32: 177-195.

Choi M, Scholl UI, Ji W, Liu T, Tikhonova IR, Zumbo P, Nayir A, Bakkaloğlu A, Ozen S, Sanjad S, Nelson-Williams C, Farhi A, Mane S, Lifton RP: Genetic diagnosis by whole exome capture and massively parallel DNA sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009, 106: 19096-19101. 10.1073/pnas.0910672106.

Zainal Ariffin O, Nor Saleha IT: NCR Report 2007. 2011, Malaysia: Ministry of Health

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F: GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC Cancer Base No. 11 [Internet]. 2013, Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer, Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr, accessed on 1/February/2014

Ayhan A, Kurman RJ, Yemelyanova A, Vang R, Logani S, Seidman JD, Shih IM: Defining the cut point between low-grade and high-grade ovarian serous carcinomas: a clinicopathologic and molecular genetic analysis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009, 33: 1220-1224. 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181a24354.

Vang R, Shih IM, Kurman RJ: Ovarian low-grade and high-grade serous carcinoma: pathogenesis, clinicopathologic and molecular biologic features, and diagnostic problems. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009, 16: 267-282. 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181b4fffa.

Gershenson DM, Sun CC, Lu KH, Coleman RL, Sood AK, Malpica A, Deavers MT, Silva EG, Bodurka DC: Clinical behavior of stage II-IV low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary. Obstet Gynecol. 2006, 108: 361-368. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000227787.24587.d1.

Malpica A, Deavers MT, Lu K, Bodurka DC, Atkinson EN, Gershenson DM, Silva EG: Grading ovarian serous carcinoma using a two-tier system. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004, 28: 496-504. 10.1097/00000478-200404000-00009.

Diaz-Padilla I, Malpica AL, Minig L, Chiva LM, Gershenson DM, Gonzalez-Martin A: Ovarian low-grade serous carcinoma: a comprehensive update. Gynecol Oncol. 2012, 126: 279-285. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.04.029.

Singer G, Oldt R, Cohen Y, Wang BG, Sidransky D, Kurman RJ, Shih IM: Mutations in BRAF and KRAS characterize the development of low-grade ovarian serous carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003, 95: 484-486. 10.1093/jnci/95.6.484.

Sieben NL, Macropoulos P, Roemen GM, Kolkman-Uljee SM, Jan Fleuren G, Houmadi R, Diss T, Warren B, Al Adnani M, De Goeij AP, Krausz T, Flanagan AM: In ovarian neoplasms, BRAF, but not KRAS, mutations are restricted to low-grade serous tumours. J Pathol. 2004, 202: 336-340. 10.1002/path.1521.

Mayr D, Hirschmann A, Lohrs U, Diebold J: KRAS and BRAF mutations in ovarian tumors: a comprehensive study of invasive carcinomas, borderline tumors and extraovarian implants. Gynecol Oncol. 2006, 103: 883-887. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.05.029.

Salani R, Kurman RJ, Giuntoli R, Gardner G, Bristow R, Wang TL, Shih IM: Assessment of TP53 mutation using purified tissue samples of ovarian serous carcinomas reveals a higher mutation rate than previously reported and does not correlate with drug resistance. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008, 18: 487-491. 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01039.x.

Kuo KT, Guan B, Feng Y, Mao TL, Chen X, Jinawath N, Wang Y, Kurman RJ, Shih IM, Wang TL: Analysis of DNA copy number alterations in ovarian serous tumors identifies new molecular genetic changes in low-grade and high-grade carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2009, 69: 4036-4042.

Ahmed AA, Etemadmoghadam D, Temple J, Lynch AG, Riad M, Sharma R, Stewart C, Fereday S, Caldas C, Defazio A, Bowtell D, Brenton JD: Driver mutations in TP53 are ubiquitous in high grade serous carcinoma of the ovary. J Pathol. 2010, 221: 49-56. 10.1002/path.2696.

Tsang YT, Deavers MT, Sun CC, Kwan SY, Kuo E, Malpica A, Mok SS, Gershenson DM, Wong KK: KRAS (but not BRAF) mutations in ovarian serous borderline tumor are associated with recurrent low-grade serous carcinoma. J Pathol. 2013, 231: 449-456. 10.1002/path.4252.

Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, Mesirov JP: Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol. 2011, 29: 24-26. 10.1038/nbt.1754.

Zhang J, Baran J, Cros A, Guberman JM, Haider S, Hsu J, Liang Y, Rivkin E, Wang J, Whitty B, Wong-Erasmus M, Yao L, Kasprzyk A: International Cancer Genome Consortium Data Portal--a one-stop shop for cancer genomics data. Database (Oxford). 2011, bar026-

Greenman C, Stephens P, Smith R, Dalgliesh GL, Hunter C, Bignell G, Davies H, Teague J, Butler A, Stevens C, Edkins S, O'Meara S, Vastrik I, Schmidt EE, Avis T, Barthorpe S, Bhamra G, Buck G, Choudhury B, Clements J, Cole J, Dicks E, Forbes S, Gray K, Halliday K, Harrison R, Hills K, Hinton J, Jenkinson A, Jones D, et al: Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature. 2007, 446: 153-158. 10.1038/nature05610.

Rubin AF, Green P: Mutation patterns in cancer genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009, 106: 21766-21770. 10.1073/pnas.0912499106.

Brosh R, Rotter V: When mutants gain new powers: news from the mutant p53 field. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009, 9: 701-713.

Marks JR, Davidoff AM, Kerns BJ, Humphrey PA, Pence JC, Dodge RK, Clarke-Pearson DL, Iglehart JD, Bast RC, Berchuck A: Overexpression and mutation of p53 in epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 1991, 51: 2979-2984.

Kang HJ, Chun SM, Kim KR, Sohn I, Sung CO: Clinical relevance of gain-of-function mutations of p53 in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. PLoS One. 2013, 8: e72609-10.1371/journal.pone.0072609.

Rivlin N, Brosh R, Oren M, Rotter V: Mutations in the p53 Tumor Suppressor Gene: Important Milestones at the Various Steps of Tumorigenesis. Genes Cancer. 2011, 2: 466-474. 10.1177/1947601911408889.

Oren M, Rotter V: Mutant p53 gain-of-function in cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010, 2: a001107-

Liu G, McDonnell TJ, Montes de Oca Luna R, Kapoor M, Mims B, El-Naggar AK, Lozano G: High metastatic potential in mice inheriting a targeted p53 missense mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000, 97: 4174-4179. 10.1073/pnas.97.8.4174.

Morton JP, Timpson P, Karim SA, Ridgway RA, Athineos D, Doyle B, Jamieson NB, Oien KA, Lowy AM, Brunton VG, Frame MC, Evans TR, Sansom OJ: Mutant p53 drives metastasis and overcomes growth arrest/senescence in pancreatic cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010, 107: 246-251. 10.1073/pnas.0908428107.

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network: Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011, 474: 609-615. 10.1038/nature10166.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Research University Funding (UKM-GUP-SK-07-19-203). The authors thank Mohd Ridhwan Abdul Razak for his expertise in Sanger sequencing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

NSAM performed bioinformatics analysis, statistical analysis, Sanger sequencing analysis and drafted the manuscript. SES, RIMY and SS carried out the next generation sequencing and validation experiment. NMM and RJ participated in the design of the study and critical evaluation of the manuscript. RRMZ validated the diagnosis of samples. AZHMD provided the clinical samples. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

13104_2014_3327_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1: Table S1: List of genes covered in the Cancer Hotspot Panel v2. Table S2. Sequencing outputs from Ion Torrent PGM. Table S3. Variant distribution of normal ovary. Figure S1. Category of DNA substitution. Majority of substitution were of transition substitution (purine-purine and pyrimidine-pyrimidine). (DOCX 200 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Ab Mutalib, NS., Syafruddin, S.E., Md Zain, R.R. et al. Molecular characterization of serous ovarian carcinoma using a multigene next generation sequencing cancer panel approach. BMC Res Notes 7, 805 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-7-805

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-7-805