Abstract

Background

To study late-life depression and its unfavourable course and co morbidities in The Netherlands.

Methods

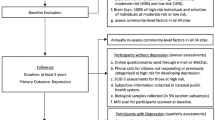

We designed the Netherlands Study of Depression in Older Persons (NESDO), a multi-site naturalistic prospective cohort study which makes it possible to examine the determinants, the course and the consequences of depressive disorders in older persons over a period of six years, and to compare these with those of depression earlier in adulthood.

Results

From 2007 until 2010, the NESDO consortium has recruited 510 depressed and non depressed older persons (≥ 60 years) at 5 locations throughout the Netherlands. Depressed persons were recruited from both mental health care institutes and general practices in order to include persons with late-life depression in various developmental and severity stages. Non-depressed persons were recruited from general practices. The baseline assessment included written questionnaires, interviews, a medical examination, cognitive tests and collection of blood and saliva samples. Information was gathered about mental health outcomes and demographic, psychosocial, biological, cognitive and genetic determinants. The baseline NESDO sample consists of 378 depressed (according to DSM-IV criteria) and 132 non-depressed persons aged 60 through 93 years. 95% had a major depression and 26.5% had dysthymia. Mean age of onset of the depressive disorder was around 49 year. For 33.1% of the depressed persons it was their first episode. 41.0% of the depressed persons had a co morbid anxiety disorder. Follow up assessments are currently going on with 6 monthly written questionnaires and face-to-face interviews after 2 and 6 years.

Conclusions

The NESDO sample offers the opportunity to study the neurobiological, psychosocial and physical determinants of depression and its long-term course in older persons. Since largely similar measures were used as in the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA; age range 18-65 years), data can be pooled thus creating a large longitudinal database of clinically depressed persons with adequate power and a large set of neurobiological, psychosocial and physical variables from both younger and older depressed persons.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The prevalence of major depression in older persons living in the community ranges from 1-5%. [1] Rates of depressive disorders are substantially higher among specific populations of older persons, ranging from 5-10% in medical outpatients to 14-42% in residents of long-term care facilities. [1] The prognosis of late-life depression is often poor. [2] It appears to have a chronic course and higher relapse rates compared to early-life depression [3–6] and co morbidity with cognitive decline and somatic diseases is higher than in depression in younger adults. [7–9] In addition, in late-life depression co morbidity with other psychiatric disorders, especially anxiety disorders is high, [10–13] and leads to longer time to remission as well as higher recurrence rates [14].

These findings suggest that the risk factors for late-life depression and its course may change during lifetime. According to the Stress-Vulnerability Model [15], the interaction of three factors is responsible for the development of depression and its course over time: vulnerability, stress and protective factors. However, vulnerability factors, stressors and protective factors may change over time, and the extent to which these factors interact and influence mental health may change as well. Former studies suggest that personality, genetic factors as well as problems at work and in family relationships may play a larger role in the onset of depression at early age, whereas late-life depression has been hypothesized to be more strongly associated with frailty-associated processes and neurodegenerative biological abnormalities. [16, 17] It is shown that psychosocial as well as biological factors play a role in (the course of) late-life depression and its co morbidities. [4, 18–23] Several of these determinants are supposed to be common in older adults, such as loneliness and losses in social environment, [24] systemic low-grade inflammation [25] and functional and cognitive limitations. [26] In addition, some of these determinants seem to function differently in older compared to younger adults, such as the hypo activation instead of hyper activation of biological stress-regulation systems; the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA)-axis and the autonomic nervous system (ANS) [27–32].

Many of these determinants for late-life depression are also interrelated, for instance, dysregulation of stress regulating systems in turn give rise to dysregulation of the immune system and to altered vascular and metabolic processes, which may ultimately have deleterious effects on the cardiovascular system, cognition and mood regulation, [33, 34] although studies in this field show conflicting results. [35] More importantly, not only can somatic diseases be a contributing or etiological factor to late-life depression, late-life depression itself also increases the risk of the development of new somatic disease, such as cardiovascular disease [23, 36–40] and diabetes mellitus [41] and of physical impairment [42].

A pronounced role for biological and neurodegenerative underlying mechanisms in (the course of) late-life depression may also explain the differences that have been found between the symptom profiles of early- and late-life depression. Compared to younger depressed adults, older depressed persons were found to show more psychomotor dysregulation and somatic disturbances such as fatigue and sleep disturbance [43, 44] and to have more apathy without the more traditional symptoms of depression [45, 46].

To better understand late-life depression, and its unfavourable course and co morbidities, we need longitudinal studies that integrate underlying psychosocial and biological vulnerability and protective mechanisms. Furthermore, it is still questioned in what way late-life depression differs from depression earlier in life. Leaving us with the question whether the concept of late-life depression is similar to that of early-life depression and, thus, to what extent we need differential diagnostic criteria and treatment strategies. To be able to make a direct comparison between early- and late-life depression we need studies that have sufficient numbers of depressed persons in all age ranges. Therefore, we designed the Netherlands Study of Depression in Older Persons (NESDO; http://nesdo.amstad.nl) in which the course of late-life depression and its co morbidities will be followed up in detail in a prospective design. To be able to make a direct comparison between early- and late-life depression, NESDO uses the same design and overlapping instruments as the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). [47] NESDA has collected data from a large cohort of persons with depressive and anxiety disorders aged 18 through 65 years (N = 2,981), which makes it possible to directly compare data from the older cohort with the existing data from depressed younger persons from NESDA (n = 1,149), thus creating a large longitudinal database of clinically depressed persons with adequate power and a large set of neurobiological, psychosocial and physical variables from both younger and older depressed persons.

Aims of the study

The first aim for NESDO is to examine the determinants of late-life depression. The second aim is to examine the course, the determinants of the course and the consequences of depressive disorders in older persons. The third aim is to compare the determinants of late-life depression, and the course and its determinants with that of early-life depression.

Methods

Sample

Recruitment of depressed older persons took place in five regions in the Netherlands from both mental health care institutes and general practitioners in order to include persons with late-life depression in various developmental and severity stages. Persons with a primary diagnosis of dementia, were suspected for dementia according to the clinician or had a Mini Mental State Examination-score (MMSE) under 18 (out of 30 points) were excluded. Also persons with insufficient command of the Dutch language were excluded. Non-depressed controls were included in order to answer research questions on the aetiology of depression, and were recruited from general practitioners. Inclusion criteria for non-depressed controls were: no lifetime diagnosis of depression or dementia, and good command of the Dutch language. Data collection of the first measurement started in 2007 and was finished in September 2010.

Three hundred and twenty-six persons of the depressed older persons (86.2% of the depressed sample) were recruited from the out- and inpatient clinics of the regional facilities for mental health care: Amsterdam (n = 113), Leiden (n = 70), Apeldoorn/Zutphen (n = 50), Nijmegen (n = 47) and Groningen (n = 46). Patients with a primary diagnosis of major depression, dysthymia or minor depression according to DSM-IV criteria [48] and who were mentally able to give written informed consent received verbal and written information about NESDO and were asked to participate. Response rates are only available from Amsterdam, but these may be considered representative for the other mental health institutions. In the region of Amsterdam, 294 persons with a depressive disorder were enrolled to the study. Of these, 291 (99%) were contacted by telephone and 3 (1.0%) could not be reached despite multiple efforts. Of the persons who were approached by telephone, 57 persons (19%) were excluded because of meeting the exclusion criteria: 23 (7.8%) had had no depressive symptoms in the past 3 months, 14 (4.7%) were not able to undergo the interview because of severe mental illness or severe physical or cognitive frailty, and 6 (2.0%) were excluded because of language problems during the phone contact. Of the remaining 234 persons who fulfilled the inclusion criteria, 121 persons (51.3%) refused and 113 (48.7%) were willing to participate in NESDO. Compared with those who refused to participate, persons who participated in the baseline interview were comparable in gender, but were younger (72.0 years versus 74.2 years, p < 0.03).

The primary care patients (n = 52) and the non-depressed control group (n = 132) were recruited from 14 general practices (GPs) in the vicinity of Amsterdam, Groningen and Leiden. Depressed persons were referred by the GPs because of depressive complaints (n = 17), or after screening with the fifteen item version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15; n = 35). [49] A screen positive score on the GDS-15 was defined as a score of 4 or higher. In total, 242 screen positive persons were contacted for a short phone-screen interview of whom 58 (24.0%) fulfilled the criteria for a current depression and the exclusion criteria. Of these, 23 (39.7%) refused to participate in the NESDO study, and 35 persons (60.3%) with a current depressive disorder underwent the baseline assessment. In addition, a random selection of screen-negative persons (n = 198) were approached for a short phone-screen and those who fulfilled the criteria for a non-depressed control and had sufficient command of the Dutch language were invited to participate in NESDO. Of these, 132 (66.7%) were willing to participate in the study.

Sample size

Our sample size calculations indicated that for cross-sectional analyses with the baseline NESDO sample and a power of 80% and an alpha of 0.05 we will be able to detect small differences with respect to clinical variables and questionnaires. For the biological determinants we need to extend the sample with persons of 60-65 years from NESDA (depressed persons: N = 77; normal controls N = 102), which results in a sample of 455 depressed and 234 non-depressed elderly, to detect moderate effects in the biological measures. When we extend the NESDO sample with younger age groups, the sample size will be suitable to detect even small effects in these biological measures.

For the analysis on the course of depression, we need a minimum of 255 persons to detect an odds ratio of 1.4 in a multiple logistic regression models with a categorical outcome variable (for instance, presence of depression diagnosis yes/no) with a power of 80% and a level of significance of 0.05. In a multiple regression models with a continuous change variable as outcome (for example change in severity of depressive symptoms), with a sample size of 255 and a power of 80% and an alpha of 0.05, we are able to detect a 5% change in the variance. So, the sample size is adequate to demonstrate statistical significances for even small differences. If we would examine change in the outcomes combining the 3 follow-up assessments using a multi-level analyses, our power would even be substantially higher than in the above described examples.

Assessment

The Stress-Vulnerability Model [15] that suggests that the interaction of vulnerability, stress and protective factors are responsible for the development of depression and its course over time has guided the selection of the instruments. The baseline assessment included internationally accepted, commonly used measures for demographic variables, depression, psychosocial variables, (chronic) stressors, activity of the HPA-axis, (re)activity of the ANS, parameters for inflammation, somatic co morbidity, cognitive functioning and the use medication and health care services (Table 1). The baseline assessment took place in the morning and lasted 3 to 4 hours. It included written questionnaires, an interview, a medical examination, assessment of the ANS (re)activity, collection of blood and instructions for sampling of the saliva. The baseline assessment was mainly performed at the different participating sites. When participants were not able to come to the site, they were interviewed at their homes. Furthermore, when necessary, the assessment was spread over two appointments. After the assessment, the participants were compensated with a small incentive (gift certificate of 15 euro and payment of travel costs) for their time and cooperation. Participants are given feedback about the research program by means of yearly newsletters. Furthermore, there was prompt response to any question or letter from the participants. Cooperation was facilitated by offering the participants a mix of self-report questionnaires, interviews, biological measures and cognitive tests.

Assessment of psychopathology

Diagnosis of depression and dysthymia according to DSM-IV-R criteria [48] is assessed with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; WHO version 2.1; life-time version). The CIDI is a structured clinical interview that is designed for use in research settings and has high validity for depressive and anxiety disorders. [9, 50] As in NESDA, we added questions to determine the research DSM-IV diagnosis of current minor depression. Severity of depression was measured using a self-report questionnaire: the Inventory of Depressive Symptoms (IDS). [51] As co morbidity with anxiety disorders is high, anxiety disorders [General Anxiety Disorder (GAD), Panic Disorder (PAN), Agoraphobia (AGO) and Social Phobia (SOC)] were also assessed using the CIDI (12 month version). Severity of anxiety symptoms was measured using the Beck Anxiety Index (BAI), [52] a self-report questionnaire. Apathy which is assumed to be more common in late-life depression compared to early-life depression was assessed using the Apathy Scale as a self-report questionnaire [53].

Vulnerability factors, stressors and protective factors

Demographic characteristics such as age, sex, ethnicity, place of living, household composition, and income were assessed with standard questions.

Psycho-social functioning

Childhood abuse, including emotional neglect as well as psychological, physical and sexual abuse, was assessed using a structured inventory. [54] Important life events during childhood and in the past years were assessed with the Brugha questionnaire. [55] Personality was assessed with the NEO-FFI, a 60 item questionnaire measuring the five personality domains neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience [56] and a short mastery scale. [57] Daily hassles were assessed using a revised version of the Worry-Scale. [58] Details about present social support from the four most intimate persons were assessed with the Close Person Inventory, [59] and a self-report questionnaire on loneliness and affiliation [60].

Somatic and health markers

The presence of chronic diseases was assessed by means of a self-report questionnaire that has previously been used in NESDA. [47] The participants were asked whether they currently or previously had any of the following chronic diseases or disease events: cardiac disease (including myocardial infarction), peripheral atherosclerosis, stroke, diabetes mellitus, COPD (asthma, chronic bronchitis or pulmonary emphysema), arthritis (rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis) or cancer, or any other disease. Compared to general practitioner information, the accuracy of self-reports of these diseases was shown to be adequate and independent of cognitive impairment [61].

Biomarkers that are parameters of cardiovascular status, immune function and metabolic syndrome were assessed in fasting blood. The interviews took place in the morning, and the respondents came in after an overnight fast. We drew 47.5 millilitres of blood which was immediately transferred to a local laboratory to start processing within an hour. Routine assays included assessment of haemoglobin, hematocrit, creatinine, total cholesterol, HDL and LDL cholesterol, glucose, triglycerides, albumin, thyroid stimulated hormone (TSH) and Free T4. The rest of the blood was processed and stored at −80°C for later assaying.

Systolic and diastolic blood pressures were measured twice in a supine position using an electronic Omron phygmomanometer. Doppler assessment of ankle and arm blood pressure allows calculation of the ankle/brachial index, which is an indicator of peripheral atherosclerosis [62].

Physical condition was assessed by means of measurement of handgrip using a hand-held dynamometer, which is an important indicator of physical frailty. Body composition assessment included objective, standardized assessments of height, weight and hip and abdominal circumference. Self reported functional limitations were assessed with the WHO-Disability Assessment Schedule. [63] Pain was assessed with the self report Chronic Graded Pain scale. [64] Sleep and insomnia was assessed with the Insomnia Rating Scale (IRS). [65] Vision and hearing were assessed with standard questions.

Physical stress regulation systems

The two most important biological stress regulation systems that have been hypothesized to be of importance in depression are the HPA-axis and the autonomic nervous system (ANS). Functioning of the HPA-axis was assessed by the use of cortisol concentrations in saliva, reflecting the free fraction of plasma cortisol, which was collected by the participants on two consecutive days. [66] Six saliva samples were taken: at the time of awakening (T1), 30 minutes post-awakening (T2), 45 minutes post-awakening (T3), 60 minutes post-awakening (T4) and at 22:00 h (T5). Dexamethasone suppression was measured by sampling the next morning at awakening (T6) after dexamethasone ingestion of 0.5 mg the night before (directly after T5). This Dexamethasone Suppression Test (DST) is a measure of HPA axis regulation and normally shows a decrease of morning cortisol concentrations due to inhibition of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) secretion after dexamethasone administration the night before. [67] The salivettes were restored in the tube labelled with date and time. After collecting all six samples, the subjects were asked to return the samples by post to the research centre. After receipt, salivettes were centrifuged at 2000 g for ten minutes, aliquoted and stored at −20°C.

The assessment of ANS functioning included heart rate, pre-ejection period and respiratory sinus arrhythmia, and was measured with the ambulatory recording system developed at the VU University in Amsterdam (VU-AMS, version 5 fs). Recording methodology of the VU-AMS as well as its reliability, validity and feasibility in large scale samples has been well documented [68, 69].

Cognitive function

Tests for several cognitive domains were assessed: the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [70] for global cognitive functioning, the abbreviated version of the Stroop Colour-word test [71] for executive functioning; the subtest Digit Span from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale [72] for motivational problems and a modified version of the Auditory Verbal Learning Test [73, 74] for memory function.

Health behaviour

Assessment of health behaviour included smoking, alcohol use, physical activities and use of health care and medication. Smoking behaviour was assessed with standard questions, and the use of alcohol was assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). [75] With the International Physical Activities Questionnaire (IPAQ) [76] energy expenditure based on sports and daily activities was calculated. Medical and psychological treatments and other professional support the persons have had for their mental and physical health problems was assessed with the Trimbos/iMTA questionnaire for Costs associated with Psychiatric Illness (TIC-P). [77] Medication use was determined by observation of the medication that the participants brought in.

Longitudinal data collection

The course of late-life depression is followed up every 6 months by means of a postal assessment that includes questionnaires on the severity of depressive symptoms and somatic health in the past 6 months, incident (chronic) stressors and functional limitations, and use of medications and health care. The questionnaires are the same questionnaires that are used during the face-to-face assessments.

A second face-to-face assessment is being performed 2 years after the baseline assessment, and is currently going on. It consists of all measures (determinants and outcome variables) that are open to change, such as severity of psychopathology and diagnostics, change in socio-demographic characteristics, all somatic health and health markers, cognitive functioning, psycho-social functioning (except for the early life events and the personality questionnaire), and health behaviour. More detailed fluctuation of depressive symptoms during the past 2 years will be assessed with a Life Chart method. This instrument uses a calendar method to re-fresh memory and then assesses presence and severity of symptoms during each month in the past two years. [78] Collection of blood and VU-AMS registration are also repeated.

The follow-up assessment lasts about 3 hours and the same instruments will be used as in the baseline assessment (see Table 1), including written questionnaires, an interview, and a medical examination. A third follow-up face-to-face assessment is planned 6 years after the baseline assessment.

Quality of the data

All interviews and physical examinations are conducted by carefully selected research assistants, mainly consisting of psychologists and mental health care nurses. The research assistants received a five day training from an experienced and certified trainer before the baseline and follow-up assessments. The research assistant is certified to conduct assessments after approval of two complete interviews which were audio taped and judged by the trainer. Question wording and probing behaviour of interviewers will frequently be monitored by checking a random selection of about 10% of all taped interviews. Data are collected with Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI) procedures on laptop computers and with self-administered questionnaires.

Data management and control

Data management of NESDO is coordinated at the Department of Psychiatry of the VUMC. The collected data from the different sites are send to the coordinating centre, where the data are entered in the central database. A special team of data managers takes care of data quality, data archiving and the creation of variables and scales. Data quality check procedures are in place and are routinely carried out to review missing data and check for inconsistencies.

Ethical issues

The study protocol of NESDO has been approved centrally by the Ethical Review Board of the VU University Medical Center, and subsequently by the local ethical review boards of the Leiden University Medical Center, University Medical Center Groningen and the Radboud University Medical Center in Nijmegen. Before participating in the study, all persons were provided with oral and written information. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants at the start of the baseline assessment. Written informed consent was asked for participating in the study, for permission to use genetic information, to retrieve medical information from the GP's, and to link information to external databases. A privacy protocol has been developed in which confidentiality of data is guaranteed by using a unique research ID number for each respondent, which enables to identify individuals without using their names. Only the data manager has access to the record that links the ID number with the name of the participant.

Results

The baseline sample consists of 378 depressed persons and 132 non-depressed controls. The overall sample has a mean age of 70.6 years (SD: 7.3; range = 60-93) and consists of 331 (64.9%) women and 179 (35.1%) men. The average years of education is 11.0 (SD = 3.6; range 5-18 years). The majority of the sample has the Dutch nationality (99.4%).

The depressive persons do not differ from the non-depressed controls with respect to mean age and sex, but they have a lower level of education, are more often divorced or widowed, and have a lower score on the MMSE (Table 2). From the depressed persons 95% has a current (six-month) major depressive disorder, 26.5% has dysthymia and 5.6% has a minor depression. 26.5% of the depressed persons have two depressive disorders, major depressive disorder and dysthymia (Table 3). Mean age of onset of the depressive disorders was around 49 years. About thirty percent of the persons with major depression (MDD) and dysthymia had an onset before the age of 40 years, whereas about 33% of the persons with MDD and 41% of the persons with dysthymia had an onset after 60 years. For 33.1% of the depressed persons it was their first episode. Severity of the depression symptoms varied between mild and very severe. Forty-one percent of the depressed persons had in the past 6 months also an anxiety disorder.

Discussion

NESDO is a multi-site naturalistic cohort study that offers us the possibility to examine the determinants, the course and consequences of depressive disorders in older persons, and to compare these with those of depression earlier in adulthood. Because of the increase of the aging population in the near future, the number of older persons suffering from (chronic) depression will further grow in the forthcoming years, and thus will become an even more relevant issue for public health care. It is of great importance to uncover mechanisms responsible for its chronic course and co morbidity. Differences in (the determinants of) the course and consequences of depression have seldom been directly compared between older and younger adults using a similar study design and with comparable instruments. Knowledge about the adequacy of the postulated differences between late-life and early-life depression is important, since it will yield important implications for mental health care practice and research. By combining data from NESDA and NESDO we will be able to address important questions that have potential relevance to the development of interventions capable of improving the course of late-life depression. The clinical relevance of the study is enhanced by the fact that several determinants of the course of depression may be used in prevention and treatment programs, which may be implemented in regular care.

Conclusions

The NESDO sample offers the opportunity to study the (determinants) of the long-term course of depression in older persons, and to pool data with NESDA. This provides us with a large (longitudinal) database of clinically depressed persons with adequate power and a large set of neurobiological, psychosocial and physical variables from both younger and older depressed persons.

References

Fiske A, Wetherell JL, Gatz M: Depression in older adults. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2009, 5: 363-389. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153621.

Hybels CF, Pieper CF, Blazer DG, Steffens DC: The course of depressive symptoms in older adults with comorbid major depression and dysthymia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008, 16: 300-309. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318162f15f.

Licht-Strunk E, Van Der Windt DA, Van Marwijk HW, De Haan M, Beekman AT: The prognosis of depression in older patients in general practice and the community. A systematic review. Fam Pract. 2007, 24: 168-180. 10.1093/fampra/cml071.

Mueller TI, Kohn R, Leventhal N, Leon AC, Solomon D, Coryell W, Endicott J, Alexopoulos GS, Keller MB: The course of depression in elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004, 12: 22-29.

Mitchell AJ, Subramaniam H: Prognosis of depression in old age compared to middle age: a systematic review of comparative studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2005, 162: 1588-1601. 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1588.

Stek ML, Van Exel E, Van Tilburg W, Westendorp RG, Beekman AT: The prognosis of depression in old age: outcome six to eight years after clinical treatment. Aging Ment Health. 2002, 6: 282-285. 10.1080/13607860220142413.

Jorm AF: Is depression a risk factor for dementia or cognitive decline? A review. Gerontology. 2000, 46: 219-227. 10.1159/000022163.

Lyness JM: Depression and comorbidity: objects in the mirror are more complex than they appear. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008, 16: 181-185. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318162f186.

Kessler RC, Birnbaum H, Bromet E, Hwang I, Sampson N, Shahly V: Age differences in major depression: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Psychol Med. 2010, 40: 225-237. 10.1017/S0033291709990213.

Beekman AT, De Beurs E, Van Balkom AJ, Deeg DJ, Van Dyck R, Van Tilburg W: Anxiety and depression in later life: Co-occurrence and communality of risk factors. Am J Psychiatry. 2000, 157: 89-95.

Lenze EJ, Mulsant BH, Shear MK, Alexopoulos GS, Frank E, Reynolds CF: Comorbidity of depression and anxiety disorders in later life. Depress Anxiety. 2001, 14: 86-93. 10.1002/da.1050.

Cairney J, Corna LM, Veldhuizen S, Herrmann N, Streiner DL: Comorbid depression and anxiety in later life: patterns of association, subjective well-being, and impairment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008, 16: 201-208.

Steffens DC: A multiplicity of approaches to characterize geriatric depression and its outcomes. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009, 22: 522-526. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32832fcd93.

Andreescu C, Lenze EJ, Dew MA, Begley AE, Mulsant BH, Dombrovski AY, Pollock BG, Stack J, Miller MD, Reynolds CF: Effect of comorbid anxiety on treatment response and relapse risk in late-life depression: controlled study. Br J Psychiatr. 2007, 190: 344-349. 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.027169.

Zubin J, Spring B: Vulnerability: A New View on Schizophrenia. J Abn Psychol. 1977, 86: 103-126.

Baldwin RC, Tomenson B: Depression in later life. A comparison of symptoms and risk factors in early and late onset cases. Br J Psychiatry. 1995, 167: 649-652. 10.1192/bjp.167.5.649.

Brodaty H, Luscombe G, Parker G, Wilhelm K, Hickie I, Austin MP, Mitchell P: Early and late onset depression in old age: different aetiologies, same phenomenology. J Affect Disord. 2001, 66: 225-236. 10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00317-7.

Gallo JJ, Richardson JP: Risk factors for depression among older adults. Md Med J. 1996, 45: 411-414.

Beekman AT, Geerlings SW, Deeg DJ, Smit JH, Schoevers RS, de Beurs E, Braam AW, Penninx BW, Van Tilburg W: The natural history of late-life depression: a 6-year prospective study in the community. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002, 59: 605-611. 10.1001/archpsyc.59.7.605.

Steunenberg B, Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, Bremmer MA, Kerkhof AJ: Mastery and neuroticism predict recovery of depression in later life. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007, 15: 234-242. 10.1097/01.JGP.0000236595.98623.62.

Cui X, Lyness JM, Tang W, Tu X, Conwell Y: Outcomes and predictors of late-life depression trajectories in older primary care patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008, 16: 406-415.

Vink D, Aartsen MJ, Schoevers RA: Risk factors for anxiety and depression in the elderly: a review. J Affect Disor. 2008, 106: 29-44. 10.1016/j.jad.2007.06.005.

Kendler KS, Gardner CO, Fiske A, Gatz M: Major depression and coronary artery disease in the Swedish twin registry: phenotypic, genetic, and environmental sources of comorbidity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009, 66: 857-863. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.94.

Ormel J, Oldehinkel AJ, Brilman EI: The interplay and etiological continuity of neuroticism, difficulties, and life events in the etiology of major and subsyndromal, first and recurrent depressive episodes in later life. Am J Psychiatry. 2001, 158: 885-891.

Bremmer MA, Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, Penninx BW, Dik MG, Hack CE, Hoogendijk WJ: Inflammatory markers in late-life depression: results from a population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2008, 106: 249-255. 10.1016/j.jad.2007.07.002.

Beekman AT, Penninx BW, Deeg DJ, De Beurs E, Geerling SW, Van Tilburg W: The impact of depression on the well-being, disability and use of services in older adults: a longitudinal perspective. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002, 105: 20-27. 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.10078.x.

Morrison MF, Redei E, TenHave T, Parmelee P, Boyce AA, Sinha PS, Katz IR: Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate and psychiatric measures in a frail, elderly residential care population. Biol Psychiatry. 2000, 47: 144-150. 10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00099-2.

Fries E, Hesse J, Hellhammer J, Hellhammer DH: A new view on hypocortisolism. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005, 30: 1010-1016. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.04.006.

Van Der Kooy KG, Van Hout HP, Van Marwijk HW, De Haan M, Stehouwer CD, Beekman AT: Differences in heart rate variability between depressed and non-depressed elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006, 21: 147-150. 10.1002/gps.1439.

Bremmer MA, Deeg DJ, Beekman AT, Penninx BW, Lips P, Hoogendijk WJ: Major depression in late life is associated with both hypo- and hypercortisolemia. Biol Psychiatry. 2007, 62: 479-486. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.033.

Penninx BW, Beekman AT, Bandinelli S, Corsi AM, Bremmer M, Hoogendijk WJ, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L: Late-life depressive symptoms are associated with both hyperactivity and hypoactivity of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007, 15: 522-529. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318033ed80.

Jindal RD, Vasko RC, Jennings JR, Fasiczka AL, Thase ME, Reynolds CF: Heart rate variability in depressed elderly. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008, 16: 861-866. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318180053d.

McEwen BS, Stellar E: Stress and the individual. Mechanisms leading to disease. Arch Intern Med. 1993, 153: 2093-2101. 10.1001/archinte.1993.00410180039004.

Glei DA, Goldman N, Chuang YL, Weinstein M: Do chronic stressors lead to physiological dysregulation? Testing the theory of allostatic load. Psychosom Med. 2007, 69: 769-776. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318157cba6.

Tiemeier H, Hofman A, Van Tuijl HR, Kiliaan AJ, Meijer J, Breteler MM: Inflammatory proteins and depression in the elderly. Epidemiology. 2003, 14: 103-107. 10.1097/00001648-200301000-00025.

Penninx BW, Guralnik JM, Mendes de Leon CF, Pahor M, Visser M, Corti MC, Wallace RB: Cardiovascular events and mortality in newly and chronically depressed persons > 70 years of age. Am J Cardiol. 1998, 81: 988-994. 10.1016/S0002-9149(98)00077-0.

Taylor WD, McQuoid DR, Krishnan KR: Medical comorbidity in late-life depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004, 19: 935-943. 10.1002/gps.1186.

Vinkers DJ, Gussekloo J, Stek ML, Westendorp RG, Van Der Mast RC: Temporal relation between depression and cognitive impairment in old age: prospective population based study. BMJ. 2004, 329: 881-10.1136/bmj.38216.604664.DE.

Bremmer MA, Hoogendijk WJ, Deeg DJ, Schoevers RA, Schalk BW, Beekman AT: Depression in older age is a risk factor for first ischemic cardiac events. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006, 14: 523-530. 10.1097/01.JGP.0000216172.31735.d5.

Wouts L, Oude Voshaar RC, Bremmer MA, Buitelaar JK, Penninx BWJH, Beekman ATF: Cardiac disease moderates the effect of depression on the risk of stroke in an elderly population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008, 596-602. 65

Pouwer F, Beekman AT, Nijpels G, Dekker JM, Snoek FJ, Kostense PJ, Heine RJ, Deeg DJ: Rates and risks for co-morbid depression in patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus: results from a community-based study. Diabetologia. 2003, 46: 892-898. 10.1007/s00125-003-1124-6.

Beekman AT, Penninx BW, Deeg DJ, Ormel J, Braam AW, Van Tilburg W: Depression and physical health in later life: results from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam (LASA). J Affect Disord. 1997, 46: 219-231. 10.1016/S0165-0327(97)00145-6.

Brodaty H, Peters K, Boyce P, Hickie I, Parker G, Mitchell P, Wilhelm K: Age and depression. J Affect Disor. 1991, 23: 137-149. 10.1016/0165-0327(91)90026-O.

Brodaty H, Luscombe G, Parker G, Wilhelm K, Hickie I, Austin MP, Mitchell P: Increased rate of psychosis and psychomotor change in depression with age. Psychol Med. 1997, 27: 1205-1213. 10.1017/S0033291797005436.

Gallo JJ, Rabins PV, Lyketsos CG, Tien AY, Anthony JC: Depression without sadness: functional outcomes of nondysphoric depression in later life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997, 45: 570-578.

Adams KB: Depressive symptoms, depletion, or developmental change? Withdrawal, apathy, and lack of vigor in the Geriatric Depression Scale. Gerontologist. 2001, 41: 768-777. 10.1093/geront/41.6.768.

Penninx BW, Beekman AT, Smit JH, Zitman FG, Nolen WA, Spinhoven P, Cuijpers P, De Jong PJ, Van Marwijk HW, Assendelft WJ, Van Der Meer K, Verhaak P, Wensing M, De Graaf R, Hoogendijk WJ, Ormel J, Van Dyck R, NESDA Research Consortium: The Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA): rationale, objectives and methods. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2008, 17: 121-140. 10.1002/mpr.256.

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 2000, Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, fourth

Yesavage JA: Geriatric Depression Scale. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988, 24: 709-711.

Wittchen HU, Robins LN, Cottler LB, Sartorius N, Burke JD, Regier D: Cross-cultural feasibility, reliability and sources of variance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). The Multicentre WHO/ADAMHA Field Trials. Br J Psychiatry. 1991, 159: 645-653. 10.1192/bjp.159.5.645. 658

Rush AJ, Gullion CM, Basco MR, Jarrett RB, Trivedi MH: The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): psychometric properties. Psychol Med. 1996, 26: 477-486. 10.1017/S0033291700035558.

Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA: An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988, 56: 893-897.

Starkstein SE, Mayberg HS, Preziosi TJ, Andrezejewski P, Leiguarda R, Robinson RG: Reliability, validity, and clinical correlates of apathy in Parkinson's disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1992, 4: 134-139.

De Graaf R, Bijl RV, Ten Have M, Beekman AT, Vollebergh WA: Pathways to comorbidity: the transition of pure mood, anxiety and substance use disorders into comorbid conditions in a longitudinal population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2004, 82: 461-467. 10.1016/j.jad.2004.03.001.

Brugha T, Bebbington P, Tennant C, Hurry J: The List of Threatening Experiences: a subset of 12 life event categories with considerable long-term contextual threat. Psychol Med. 1985, 15: 189-194. 10.1017/S003329170002105X.

Costa PT, McCrae RR: Domains and facets: hierarchical personality assessment using the revised NEO personality inventory. J Pers Assess. 1995, 64: 21-50. 10.1207/s15327752jpa6401_2.

Pearlin LI, Schooler C: The structure of coping. J Health Soc Behav. 1978, 19: 2-21. 10.2307/2136319.

Wisocki PA, Handen B, Morse CK: The worry scale as a measure of anxiety among homebound and community active elderly. Behav Therapist. 1986, 5: 91-95.

Stansfeld S, Marmot M: Deriving a survey measure of social support: the reliability and validity of the Close Persons Questionnaire. Soc Sci Med. 1992, 35: 1027-1035. 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90242-I.

De Jong Gierveld J, Kamphuis FH: The development of a rasch type loneliness scale. Appl Psychol Measurements. 1985, 9: 289-299. 10.1177/014662168500900307.

Kriegsman DM, Penninx BW, Van Eijk JT, Boeke AJ, Deeg DJ: Self-reports and general practitioner information on the presence of chronic diseases in community dwelling elderly. A study on the accuracy of patients' self-reports and on determinants of inaccuracy. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996, 49: 1407-1417. 10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00274-0.

Newman AB, Siscovick DS, Manolio TA, Polak J, Fried LP, Borhani NO, Wolfson SK: Ankle-arm index as a marker of atherosclerosis in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Cardiovascular Heart Study (CHS) Collaborative Research Group. Circulation. 1993, 88: 837-845.

Chwastiak LA, Von Korff M: Disability in depression and back pain: evaluation of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO DAS II) in a primary care setting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003, 56: 507-514. 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00051-9.

Von Korff M, Miglioretti DL: A prognostic approach to defining chronic pain. Pain. 2005, 117: 304-313. 10.1016/j.pain.2005.06.017.

Levine DW, Kaplan RM, Kripke DF, Bowen DJ, Naughton MJ, Shumaker SA: Factor structure and measurement invariance of the Women's Health Initiative Insomnia Rating Scale. Psychol Assess. 2003, 15: 123-136.

Würst S, Wolf J, Hellhammer DH, Dechoux R, Kumsta R, Kirschbaum C: The cortisol awakening response, normal values and confounds. Noise Health. 2000, 29: 174-184.

American Psychiatric Association: The dexamethasone suppression test: an overview of its current status in psychiatry. The APA task force on Laboratory tests in psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry. 1987, 144: 1253-62.

De Geus EJ, Willemsen GH, Klaver CH, van Doornen LJ: Ambulatory measurement of respiratory sinus arrhythmia and respiration rate. Biol Psychol. 1995, 41: 205-227. 10.1016/0301-0511(95)05137-6.

Licht CM, De Geus EJ, Zitman FG, Hoogendijk WJ, Van Dyck R, Penninx BW: Association between major depressive disorder and heart rate variability in the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008, 65: 1358-1367. 10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1358.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psych Res. 1975, 12: 189-198. 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6.

Stroop JR: Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J Exp Psychol. 1935, 18: 643-662.

Wechsler D: The measurement and appraisal of adult intelligence. 1958, Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 4

Rey A: L'examen clinique en psychologie. 1964, Presses Universitaire de France, Paris, France

Van Der Elst W, Van Boxtel MP, Van Breukelen GJ, Jolles J: Rey's verbal learning test: normative data for 1855 healthy participants aged 24-81 years and the influence of age, sex, education, and mode of presentation. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2005, 11: 290-302.

Babor TF, Kranzler HR, Lauerman RJ: Early detection of harmful alcohol consumption: comparison of clinical, laboratory, and self-report screening procedures. Addict Behav. 1989, 14: 139-157. 10.1016/0306-4603(89)90043-9.

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, Pratt M, Ekelund U, Yngve A, Sallis JF, Oja P: International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003, 35: 1381-1395. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB.

Hakkaart-van Roijen L: Trimbos/iMTA questionnaire for costs associated with psychiatric illness (TIC-P). 2002, Rotterdam: Institute for Medical Technology Assessment

Lyketsos CG, Nestadt G, Cwi J, Heithoff K, Eaton WW: The lifechart method to describe the course of psychopathology. Int J Methods Psychiatry Res. 1994, 4: 143-155.

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The infrastructure for NESDO is funded through the Fonds NutsOhra, Stichting tot Steun VCVGZ, NARSAD The Brain and Behaviour Research Fund, and the participating universities and mental health care organizations (VU University Medical Center, Leiden University Medical Center, University Medical Center Groningen, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, and GGZ inGeest, GGNet, GGZ Nijmegen, GGZ Rivierduinen, Lentis, and Parnassia).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors are key members of the research consortium and have made substantial contributions to the conception and the design of the study, and acquisition of the baseline data. They have all been involved in writing the manuscript and have given their approval for the final version.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Comijs, H.C., van Marwijk, H.W., van der Mast, R.C. et al. The Netherlands study of depression in older persons (NESDO); a prospective cohort study. BMC Res Notes 4, 524 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-4-524

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-4-524