Abstract

Despite the theoretical and experimental progress, our understanding on sex chromosome differentiation is still diagrammatic. The accumulation of repetitive DNA sequences is believed to occur in early stages of such differentiation. As fish species present a wide range of sex chromosome systems they are excellent models to examine the differentiation of these chromosomes. In the present study, the chromosomal distribution of 9 mono-, di- and tri-nucleotide microsatellites were analyzed using fluorescence in situ hybrization (FISH) in rock bream fish (Oplegnathus fasciatus), which is characterized by an X1X2Y sex chromosome system. Generally, the males and females exhibited the same autosomal pattern of distribution for a specific microsatellite probe. The male specific Y chromosome displays a specific amount of distinct microsatellites repeats along both arms. However, the accumulation of these repetitive sequences was not accompanied by a huge heterochromatinization process. The present data provide new insights into the chromosomal constitution of the multiple sex chromosomes and allow further investigations on the true role of the microsatellite repeats in the differentiation process of this sex system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The origin and evolution of sex chromosomes are among the most interesting topics in evolutionary genetics. Although sex chromosomes evolve from a homologue pair of autosomes, over time they become different, both from each other and the autosomes, in gene content and structure[1, 2]. The processes working on sex chromosome differentiation are still not completely understood. However, the accumulation of repetitive DNA sequences is one of the first probable steps in the early stages of such differentiation[2–4]. Repetitive sequences, which can account for more than 50% of the genome, constitute the substantial portion of eukaryotic genomes and include the tandem repeats (satellites, minisatellites and microsatellites) and dispersed elements (transposons and retrotransposons) (reviewed in[5]). A clear correlation between sex chromosomes and repetitive DNAs has been evidenced by a number of studies[4, 6–11], suggesting that the differentiation of sex chromosomes is frequently associated with the accumulation of such repetitive sequences. The chromosomal mapping of repetitive DNAs has provided new insights for understanding genome evolution and was useful to reveal the process of sex chromosome differentiation in many vertebrate species.

Teleost fishes are an outstanding model to study the evolution of sex chromosome since they present a broad range of sex chromosome systems, as well as the absence of differentiated sex chromosomes in most species[12, 13]. Besides, they have much younger sex chromosomes compared to higher vertebrates, such as mammals and birds, making it possible to analyze the early stage of their differentiation[2, 14, 15]. Particularly, repeated DNA sequences have been applied to clarify the potential role of these sequences in the differentiation of fish chromosomes (reviewed in[16]).

The rock bream (Oplegnathus fasciatus) belongs to the Oplegnathidae family and is one of the most economically important marine fish in East Asia[17]. Conventional cytogenetic analysis of this species showed that the male karyotype is composed of 2n = 47 chromosomes (3 m + 44a), while the female karyotype is composed of 2n = 48 chromosomes (2 m + 46a). This species is characterized by having a multiple X1X1X2X2/X1X2Y sex chromosome system[18, 19]. To further understanding of sex chromosome differentiation in Oplegnathus fasciatus, we mapped the chromosomal distribution of different classes of microsatellite repeats in the genome of Oplegnathus fasciatus, focusing on their distribution within the sex chromosomes.

Results

Karyotyping

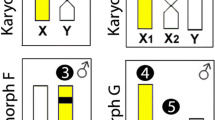

Oplegnathus fasciatus showed 2n = 48 chromosomes (46a + 2 m) in the female and 2n = 47 chromosomes (44a + 3 m) in the male specimens. This specific sex karyotype is determined by the characteristic multiple sex chromosome system, with X1X1X2X2 chromosomes in the females and X1X2Y chromosomes in the males, where the Y chromosome corresponds to a metacentric one, easily recognized by its larger size compared to the other chromosomes. Differently, the X1 and X2 chromosomes are acrocentrics and not easily identifiable. Thus, both chromosomes were tentatively located as the 14th and 22nd pairs in the karyotype, respectively (Figure 1).

Chromosomal mapping of the microsatellite repeats

In general, the same distribution pattern was found between males and females when looking at the mapping of a specific microsatellite probe in the autosomes. A discrete banding pattern was observed for some microsatellites, whereas others were more widely dispersed along the chromosomes. However, the Y chromosome demonstrated a remarkable and specific accumulation of several microsatellites.

The microsatellites d(CA)15, d(GA)15, d(CAT)10 and d(GAG)10, provided preferential banding pattern in the subtelomeric region along most chromosome arms, with some signals appearing stronger and more extended than the others. The microsatellites d(GC)15 and d(CAA)10 provided strong dispersed signals across the entire length of most chromosomes, highlighting their widespread presence in the genome of Oplegnathus fasciatus. In addition, d(A)30 d(CAG)10 and d(CGG)10 produced also a scattered, but more discrete distribution in the chromosomes (Figure 2).

Mitotic metaphase chromosomes of Oplegnathus fasciatus males with an X 1 X 2 Y sex chromosome system, hybridized with different labeled microsatellite-containing oligonucleotides. Chromosomes were counterstained with DAPI (blue) and microsatellites probes were directly labeled with Cy3 during synthesis (red signals). Letters mark the Y chromosomes. Bar = 5 μm.

The specific male Y chromosome is easily characterized by a strong concentration of some microsatellite repeats. Particularly the microsatellites d(GC)15 and d(CAA)10 are highly distributed in the Y chromosome, being practically accumulated along its entire length. A stronger, but less concentrated distribution, was also observed for microsatellites d(A)30 and d(CAG)10, while the microsatellites d(CA)15, d(CGG)10, d(GA)15, d(CAT)10 and (dGAG)10 were preferentially clustered on specific regions of the chromosome. Figure 3 highlights the overall distribution of all microsatellites on the Y chromosome.

Discussion

Chromosomal distribution of microsatellites on autosomes

Our results were able to evidence that the distribution of the microsatellites in the chromosomes of the rock bream fish differs among the distinct repeats analyzed. Indeed, a strong accumulation occurs for some of them, as is the case of the d(GC)15 and d(CAA)10 repeats, while others have a distinct and more discrete distribution pattern. Thus, the genome of the rock bream shows a clear differential accumulation of microsatellites along its evolutionary time. Similarly, some of these microsatellites were also found to be clustered in other fish species, such as in the Silurformes Imparfinis schubarti (Heptapteridae), Steindachneridion scripta (Pimelodidae) and Rineloricaria latirostris (Loricariidae), which exhibit a remarkable accumulation of both (GA)15 and (A)30 microsatellites in the telomeric regions of their chromosomes[20]. In two karyomorphs of Hoplias malabaricus ‘species complex’, one of them displaying an XY sex chromosome system and the other one an X1X2Y multiple system, the (GA)15 and (CA)15 repeats are preferentially located in the subtelomeric regions[21]. This preferential accumulation in particular locations may indicate chromosomal regions where microsatellites are present as very large perfect or degenerate arrays[4]. However, it is known that microsatellite repeats can also exhibit wide diversity with respect to chromosomal location and distribution[16]. For example, the microsatellites d(GC)15 and d(CAA)10, which provided the strongest dispersed signals across the entire length of most chromosomes in rock bream, were found to have a subtelomeric location in H. malabaricus[21]. As a whole, these data demonstrate the dynamism in respect to the accumulation and distribution of repetitive DNAs on fish genomes.

Patterns of microsatellite distribution on Y chromosome

Multiple sex chromosomes in fishes usually arise from centric or tandem fusions between ancestral sex chromosomes[15, 22], and repetitive DNA sequences have proven to be useful markers of these processes. This is the case for d(GAG)10 repeats in the present study. Indeed, this microsatellite showed a general location in the telomeric region of the chromosomes (Figure 2). In addition, this same microsatellite provided a clear banding pattern not only in the telomeric regions of the Y chromosome, but also on its centromeric region. Whereas this chromosome was originated from a centric fusion that merged the ancestral homologues of the X1 and X2 chromosomes, this centromeric site is a clear indicator of that chromosomal rearrangement.

On the other hand, other microsatellites have a wide distribution along the Y chromosome, particularly the d(GC)15 and d(CAA)10, and even the d(A)30 d(CAG)10 ones. The accumulation of repetitive DNA sequences was likely to play an important role in the differentiation process of sex chromosomes, especially XY and ZW sex systems[16]. Suppression of recombination is a prerequisite for stable genetically determined sex systems, and thus the massive accumulation of repetitive sequences, including microsatellites, usually occurs in non-recombining regions[2]. In simple sex systems, the repetitive DNAs usually accumulate in the heterochromatic regions, thereby forming heterochromatic block which could drive the divergence of sex chromosomes[2, 23, 24].

Although the association of repetitive DNA sequences with the differentiation of multiple sex chromosome systems has also been testified, there is no significant increase of heterochromation in such multiple sex chromosomes. For example, in H. malabaricus as well as E. erythrinus, the multiple sex chromosomes do not display a great amount of heterochromatin[15, 25]. Furthermore, the heterochromatin that is present in the sex chromosomes is ‘pre-existing’, with no significant increase on its amount after the differentiation of the multiple systems. These evidences indicated that the differentiation of multiple sex system is achieved through chromosomal rearrangements that occurred during their own origin[21]. Thus, chromosomal rearrangements may create new linkage groups between genes that were originally found in different chromosomes, including sexually antagonistic ones. This may lead to reduced or suppressed recombination in regions close to the breakpoints in the heterozygote[26]. Concerning O. fasciatus the conspicuous amount of microsatellite repeats in the Y chromosome is yet an open question which deserves further investigation. As we have not at this moment a clear identification of the X1 and X2 chromosomes in the karyotype, it is not clear if these repeats were already present in the ancestral chromosomes or if they have been accumulated after the fusion process originating the neo-Y chromosome. In the latter case, we would have a clear example of a huge accumulation of repetitive DNAs on the sex specific chromosome and this would be an interesting novelty relative to a multiple sex chromosome system, keeping also in mind that our previous C-banding data showed that no huge heterochromatic content is presented in the Y chromosomes of O. fasciatus[18, 19].

Conclusions

In summary, O. fasciatus has a characteristic X1X2Y sex chromosome system in which the large metacentric Y chromosome displays a specific amount of distinct microsatellites repeats along both arms. In addition, several autosomes also show a conspicuous distribution pattern of these DNA repeats, showing that several classes of repetitive DNA sequences have an important role in the genome differentiation of this species, including the sex chromosomes. However, the accumulation of these repetitive sequences was not accompanied by a huge heterochromatinization process. At the moment, the present data provide new insights into the chromosomal constitution of multiple sex chromosomes and allow further investigations on the true role of the microsatellite repeats in the differentiation process of this sex system.

Methods

Specimens, mitotic chromosome preparation, chromosome staining and karyotyping

A total of 30 adult fish (18 females and 12 males), with easily recognizable tests or ovaries, were collected from the coast of Zhoushan (Zhejiang Province) (Figure 4). Mitotic chromosome preparations were obtained by the air-drying method. The specimens were injected with 0.05% colchicine for 3 hours. The kidney tissue was collected and placed in hypotonic 0.075 mol/l KCl solution for 30 minutes, to obtaining a cell suspension. The cells were fixed in Carnoy’s solution (methanol: acetic acid, 3: 1, v/v). Afterwards, the cells were dropped on cooled clean glass slides, air-dried and stained with 15% Giemsa solution diluted with phosphate buffer (pH 6.8).

Fluorescence in situ hybridization on mitotic spreads

Fluorescence in situ hybridization experiments were performed as described in[4] with slight modifications. We used the following labeled oligonucleotides as probes: d(A)30, d(CA)15, d(GA)15, d(GC)15, d(CAA)10, d(CAG)10, d(CAT)10, d(GAG)10 and d(CGG)10. These sequences were directly labeled with Cy3 at 5′ terminal during synthesis by Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). The chromosomes were counterstained with DAPI (1.2 μg/ml), mounted in antifade solution (Vector, Burlingame, CA, USA), and analyzed in an epifluorescence microscope Olympus BX50 (Olympus Corporation, Ishikawa, Japan).

Approximately 30 metaphase spreads were analyzed per specimen to determine the diploid chromosome number and karyotype structure. The chromosomes were classified as metacentric (m) or acrocentric (a) according to arm ratios[27].

Abbreviations

- 2n:

-

Diploid number

- a:

-

Acrocentric chromosome

- DAPI:

-

4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- FISH:

-

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

- m:

-

Metacentric chromosome

References

Kejnovsky E, Hobza R, Cermak T, Kubat Z, Vyskot B: The role of repetitive DNA in structure and evolution of sex chromosomes in plants. Heredity 2009, 102: 533–541. 10.1038/hdy.2009.17

Charlesworth D, Charlesworth B, Marais G: Steps in the evolution of heteromorphic sex chromosomes. Heredity 2005, 95: 118–128. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800697

Hobza R, Lengerova M, Svoboda J, Kubekova H, Kejnovsky E, Vyskot B: An accumulation of tandem DNA repeats on the Y chromosome in Silene latifolia during early stages of sex chromosome evolution. Chromosoma 2006, 115: 376–382. 10.1007/s00412-006-0065-5

Kubat ZKZ, Hobza RHR, Vyskot BVB, Kejnovsky EKE: Microsatellite accumulation on the Y chromosome in Silene latifolia . Genome 2008, 51: 350–356. 10.1139/G08-024

López-Flores I, Garrido-Ramos MA: The repetitive DNA content of eukaryotic genomes. In Repetitive DNA. Genome Dynamics. Volume 7. Edited by: Garrido-Ramos MA. Basel: Karger; 2009:1–28.

Mazzuchelli J, Martins C: Genomic organization of repetitive DNAs in the cichlid fish Astronotus ocellatus . Genetica 2009, 136: 461–469. 10.1007/s10709-008-9346-7

Mariotti B, Manzano S, Kejnovsk E, Vyskot B, Jamilena M: Accumulation of Y-specific satellite DNAs during the evolution of Rumex acetosa sex chromosomes. Mol Genet Genomics 2009, 281: 249–259. 10.1007/s00438-008-0405-7

Ferreira IA, Poletto AB, Kocher TD, Mota-Velasco JC, Penman DJ, Martins C: Chromosome evolution in African cichlid fish: contributions from the physical mapping of repeated DNAs. Cytogenet Genome Res 2010, 129: 314–322. 10.1159/000315895

Cioffi MB, Martin C, Bertollo LAC: Chromosome spreading of associated transposable elements and ribosomal DNA in the fish Erythrinus erythrinus. Implications for genome change and karyoevolution in fish. BMC Evol Biol 2010, 10: 271. 10.1186/1471-2148-10-271

Cioffi MB, Camacho JPM, Bertollo LAC: Repetitive DNAs and differentiation of sex chromosomes in Neotropical fishes. Cytogenet Genome Res 2011, 132: 188–194. 10.1159/000321571

Silva EL, Borba RP, Parise-Maltempi PP: Chromosome mapping of repetitive sequences in Anostomidae species: implications for genomic and sex chromosome evolution. Mol Cytogenet 2012, 5: 45. 10.1186/1755-8166-5-45

Devlin RH, Nagahama Y: Sex determination and sex differentiation in fish: an overview of genetic, physiological, and environmental influences. Aquaculture 2002, 208: 191–364. 10.1016/S0044-8486(02)00057-1

Volff JN: Genome evolution and biodiversity in teleost fish. Heredity 2004, 94: 280–294.

Bachtrog D: A dynamic view of sex chromosome evolution. Curr Opin Genetics Dev 2006, 16: 578–585. 10.1016/j.gde.2006.10.007

Cioffi MB, Bertollo LAC: Initial steps in XY chromosome differentiation in Hoplias malabaricus and the origin of an X 1 X 2 Y sex chromosome system in this fish group. Heredity 2010, 105: 554–561. 10.1038/hdy.2010.18

Cioffi MB, Bertollo LAC: Chromosomal distribution and evolution of repetitive DNAs in fish. In Repetitive DNA. Genome Dynamics. Volume 7. Edited by: Garrido-Ramos MA. Basel: Karger; 2009:197–221.

Meng QW, SU JX, Miao XZ: Fish taxonomy. Beijing: China Agriculture Press; 1995.

Xu D, You F, Lou B, Geng Z, Li J, Xiao ZZ: Comparative analysis of karyotype and C-banding in male and female Oplegnathus fasciatus . Acta Hydrobiol Sinica 2012, 36: 552–557.

Xu D, Lou B, Xu H, Li S, Geng Z: Isolation and characterization of male-specific DNA markers in the rock bream Oplegnathus fasciatus . Mar Biotechnol 2012, 15: 221–229.

Vanzela ALL, Swarça AC, Dias AL, Stolf R, Ruas PM, Ruas CF, Sbalgueiro IJ, Giuliano-Caetano L: Differential distribution of (GA)9 + C microsatellite on chromosomes of some animal and plant species. Cytologia 2002, 67: 9–13. 10.1508/cytologia.67.9

Cioffi MB, Kejnovsky E, Bertollo LAC: The chromosomal distribution of microsatellite repeats in the genome of the wolf fish Hoplias malabaricus , focusing on the sex chromosomes. Cytogenet Genome Res 2011, 132: 289–296. 10.1159/000322058

Almeida-Toledo LF, Daniel-Silva MFZ, Lopes CE, Toledo-Filho SA: Sex chromosome evolution in fish. II. Second occurrence of an X 1 X 2 Y sex chromosome system in Gymnotiformes. Chromosome Res 2000, 8: 335–340. 10.1023/A:1009287630301

Oliveira C, Wright JM: Molecular cytogenetic analysis of heterochromatin in the chromosomes of tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus (Teleostei: Cichlidae). Chromosome Res 1998, 6: 205–211. 10.1023/A:1009211701829

Takehana Y, Naruse K, Asada Y, Matsuda Y, Shin-I T, Kohara Y, Fujiyama A, Hamaguchi S, Sakaizumi M: Molecular cloning and characterization of the repetitive DNA sequences that comprise the constitutive heterochromatin of the W chromosomes of medaka fishes. Chromosome Res 2012, 20: 71–81. 10.1007/s10577-011-9259-7

Cioffi MB, Molina WF, Moreira-Filho O, Bertollo LAC: Chromosomal distribution of repetitive DNA sequences highlights the independent differentiation of multiple sex chromosomes in two closely related fish species. Cytogenet Genome 2011, 134: 295–302. 10.1159/000329481

Vieira CP, Coelho PA, Vieira J: Inferences on the history of the Drosophila americana polymorphic X/4 fusion from patterns of polymophism at the X-linked paralytic and elav genes. Genetics 2003, 164: 1459–1469.

Levan A, Fredga K, Sandberg AA: Suggestion for a chromosome nomenclature based on centromeric position. Hereditas 1964, 52: 201–220.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Brazilian agencies FAPESP (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo) and CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico), and by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41106114), the National Science and Technology Pillar Program of China (2011BAD13B08), and the Project of Zhejiang Province of China (2010R50025; 2010 F20006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

XD carried out the conventional cytogenetic analysis, coordinated the study and drafted the manuscript, LB helped in the conventional cytogenetic analysis and drafted the manuscript, LACB drafted and revised the manuscript, MBC carried out the molecular cytogenetic analysis, drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, D., Lou, B., Bertollo, L.A.C. et al. Chromosomal mapping of microsatellite repeats in the rock bream fish Oplegnathus fasciatus, with emphasis of their distribution in the neo-Y chromosome. Mol Cytogenet 6, 12 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1755-8166-6-12

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1755-8166-6-12