Abstract

Background

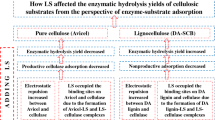

Thermochemical pretreatment of lignocellulose is crucial to bioconversion in the fields of biorefinery and biofuels. However, the enzyme inhibitors in pretreatment hydrolysate make solid substrate washing and hydrolysate detoxification indispensable prior to enzymatic hydrolysis. Sulfite pretreatment to overcome recalcitrance of lignocelluloses (SPORL) is a relatively new process, but has demonstrated robust performance for sugar and biofuel production from woody biomass in terms of yield and energy efficiency. This study demonstrated the advantage of SPORL pretreatment whereby the presentation of lignosulfonate (LS) renders the hydrolysate non-inhibitory to cellulase (Cel) due to the formation of lignosulfonate-cellulase complexes (LCCs) which can mediate the Cel adsorption between lignin and cellulose, contrary to the conventional belief that pretreatment hydrolysate inhibits the enzymatic hydrolysis unless detoxified.

Results

Particular emphasis was made on the formation mechanisms and stability phase of LCCs, the electrostatic interaction between LCCs and lignin, and the redistributed Cel adsorption between lignin and cellulose. The study found that LS, the byproduct of SPORL pretreatment, behaves as a polyelectrolyte to form LCCs with Cel by associating to the oppositely charged groups of protein. Compared to Cel, the zeta potential of LCCs is more negative and adjustable by altering the molar ratio of LS to Cel, and thereby LCCs have the ability to mitigate the nonproductive binding of Cel to lignin because of the enlarged electrostatic repulsion. Experimental results showed that the benefit from the reduced nonproductive binding outweighed the detrimental effects from the inhibitors in pretreatment hydrolysate. Specifically, the glucan conversions of solid substrate from poplar and lodgepole pine were greatly elevated by 25.9% and 31.8%, respectively, with the complete addition of the corresponding hydrolysate. This contradicts the well-acknowledged concept in the fields of biofuels and biorefinery that the pretreatment hydrolysate is inhibitory to enzymes.

Conclusions

The results reported in this study also suggest significant advantages of SPORL pretreatment in terms of water consumption and process integration, that is, it should abolish the steps of solid substrate washing and pretreatment hydrolysate detoxification for direct simultaneous saccharification and combined fermentation (SSCombF) of enzymatic and pretreatment hydrolysate, thereby facilitating bioprocess consolidation. Furthermore, this study not only has practical significance to biorefinery and bioenergy, but it also provides scientific importance to the molecular design of composite enzyme-polyelectrolyte systems, such as immobilized enzymes and enzyme activators, as well as to the design of enzyme separation processes using water-soluble polyelectrolytes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lignocellulose represents a key sustainable source of biomass for transformation into biofuels and bio-based products. However, the lignin-polysaccharide cross-linking structure of lignocellulose makes it recalcitrant to biotransformation, both microbial and enzymatic. For this reason, thermochemical strategies are widely implemented to make lignocellulose accessible to cellulase (Cel) by liberating polysaccharides from the lignin seal [1]. Considering the protection of sugars from undesired degradation, it is impossible to attain the complete removal of lignin for the existing thermochemical pretreatments, especially for feedstocks with high lignin content, such as forest biomass [2]. The residual lignin in solid substrate tends to adsorb the enzyme nonproductively and irreversibly during enzymatic hydrolysis, not only violating the selectivity of enzymatic catalysis, but also leading to enzyme deactivation [3, 4]. Furthermore, the thermochemical pretreatment invariably involves the degradation of lignocellulose. Some byproducts of pretreatment may act as inhibitors to enzymes and microorganisms, such as furfural and hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF), which are regarded as the most toxic inhibitors present in pretreatment hydrolysate [5]. In this context, the washing of solid substrate and detoxification of pretreatment hydrolysate have to be indispensably performed prior to enzymatic hydrolysis or fermentation, which not only result in tremendous consumption of water and energy, but also complicate the bioconversion process. On the whole, the nonproductive binding and inhibitory effects are the main obstacles to the sustainable development of biofuels in the upstream processes of bioconversion.

Various approaches have been applied to reduce the nonproductive Cel binding, including genetic [6, 7] and chemical [8] modification of lignin, specific lignin removal [9, 10], and lignin shielding by BSA [11] or surfactant [12, 13]. These approaches are somewhat effective in mitigating the enzyme-lignin interaction, but further complicate the process and make the bioconversion unprofitable due to the additional expense. To liberate Cel molecules from the effects of lignin, we proposed sulfite pretreatment to overcome recalcitrance of lignocellulose (SPORL), as reported previously [14]. Recently, efforts contributed to the study of lignin modification and the resultant reduction of the nonproductive binding. Firstly, sulfonation modification occurs to lignin during SPORL pretreatment, which makes lignin negatively charged. Because the ionization of the sulfonic acid group on lignin is pH-dependent, elevating pH was observed to be effective to reduce the nonproductive binding. This mechanism was recently reported by Lan et al. [15], which is similar to the mechanism proposed by Del Rio that the sulfonation of lignin was effective for cellulolytic hydrolysis improvement due to the increase of free enzymes [16]. Secondly, lignosulfonate (LS), a byproduct of SPROL in pretreatment hydrolysate, has a unique irregular structure with a non-charged core consisting of cross-linked aromatic chains with all sulfonic acid groups relocated to or near the molecule surface to facilitate interactions with the aqueous surroundings. Although the overall structure of LS is not known, it possesses the same ionizable groups as polyacrylamidomethylpropyl sulfonate (PAMPS), an anionic polyelectrolyte that can bind BSA and form a complex, as reported by Mattison [17]. Therefore, we hypothesize that the LS is likely to associate and form LS-Cel complexes (LCCs) with Cel by acting as a polyelectrolyte. If this is the case, the resultant LCCs will be more negatively charged, and thereby the electrostatic repulsive force between lignin and enzymes (LCCs) will become stronger. This will result in the redistribution of Cel adsorption on lignin and cellulose, and definitely mitigate the nonproductive binding and promote the enzymatic saccharification of lignocellulosic substrate. Furthermore, such interaction is supposed to be adjustable since the surface charge of LCCs is dependent on the proportion of LS at a given pH value. In this case, the pretreatment hydrolysate that was considered to be inhibitory to enzymes and yeast [5, 18] may not have to be detoxified prior to enzymatic saccharification or fermentation, provided the constructive effects from LCCs outweigh the detrimental effects from inhibitors in the pretreatment hydrolysate. In fact, our latest study showed that up to 90% of cellulose saccharification was achieved for SPORL-pretreated lodgepole pine at Cel loading of 13 FPU/g glucan with the application of its corresponding pretreatment hydrolysate coupled with increasing enzymatic hydrolysis pH to above 5.5, compared with only 51% for the control run without hydrolysate application at pH 5.0 [19]. This provides great advantage for SPORL in terms of water consumption and process consolidation. However, we ascribed the enhanced enzymatic saccharification to the role of LS as surfactant in the last study [19], rather than the role of water-soluble anionic polyelectrolyte that is now supposed to form complexes with Cel.

The interactions between polyelectrolytes and proteins have been extensively studied in a variety of contexts, such as DNA replication and gene regulation [20], protein purification [21, 22] and separation [23], enzyme immobilization [24, 25] and activity control [26, 27], and polymer-mediated drug delivery [28, 29]. Since LS can interact with proteins, it has been exploited as a precipitator for protein recovery [30, 31], a bypass protein for ruminants to improve nutrition uptake [32, 33], and an organic fertilizer for maize metabolism by enhancing enzyme activity [34]. However, the interaction between LS and Cel has not received enough attention in the aspect of biofuel production. The present study was carried out to clarify the formation of LCCs, and elucidate its role of mediating the Cel adsorption between lignin and cellulose. In addition, the effects of LCCs on enzymatic saccharification of lignocellulose were evaluated.

Results and discussion

Interactions between Cel and LS

Cel, a protein-based amphoteric molecule in nature, contains both acidic and basic functional groups. The net charge on Cel is affected by the pH of its surrounding environment, and can become more positively or negatively charged due to the loss or gain of protons (Figure 1). The isoelectric point (pI) of Cel was attained at pH 3.6. The separated LS from SPROL hydrolysate, which possesses sulfonic acid groups, has an electronegative potential that is far less than that of Cel at the same pH. Similarly, the net charge of LS is also dependent on the pH of the solution as shown in Figure 1. In the optimal range of pH for Cel activity from 4.5 to 6.0, both Cel and LS are negatively charged, and thereby the nonflexible Cel molecules can only associate with the flexible LS through the stoichiometric formation of ion pairs, that is, the integration of the amino group in Cel and sulfonic acid group in LS, as the schematic representation demonstrates in Figure 2. To verify the complexation of LS and Cel, LS solution was mixed with Cel solution at pH 4.8. The mixture was then subjected to dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis after equilibrium. Figure 2 shows the size distributions of Cel, LS, and LCCs in mixtures with different molar ratios of Cel to LS. The unimodal distribution with an apparent diameter of 10 nm corresponds to Cel, and the peak at 126 nm represents LS. For mixture A with excess Cel (Cel/LS = 104/3), the negative charge on LS was not sufficient to capture the Cel molecules as indicated by the peaks at 10 nm and 385 nm, which correspond to the free Cel and LCCs, respectively. The increased fraction of LS in mixture B (Cel/LS = 104/20) resulted in total complexation as indicted by the only peak of LCCs with larger size at 937 nm (Figure 2). From another perspective, the complexation can be considered as enzyme immobilization just as Haupt et al. reported that glucoamylase and β-glucosidase were immobilized on a novel type of colloidal particle consisting of a poly(styrene) core and long chains of poly(styrene sulfonic acid) brush [35].

Intensity size distributions for Cel (1.5 mg/mL, MW = 50 kDa), LS (3.4 mg/mL, MW = 4,200 Da), and LCCs in mixtures. The molar ratio of Cel to LS is 104/3 in mixture A (800 μL Cel and 10 μL LS), and 104/20 in mixture B (800 μL Cel and 60 μL LS). DLS analysis was conducted in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer at pH 4.8 and 25°C after the required time of 60 minutes for equilibrium. The figure insert is the schematic presentation of the formation of LCCs. Cel, cellulase; DLS, dynamic light scattering; LCC, lignosulfonate-cellulase complex; LS, lignosulfonate; MW, molecular weight.

Since LS behaves as a branched polyelectrolyte with flexible negatively charged chains, the entrapment of Cel by the chains of LS is considered to be efficient and fast. Figure 3 provides information about the process of the formation of LCCs in mixture A. The entrapment was accomplished within 15 minutes as indicated by DLS intensity of Cel at 10 nm, but the LCCs kept dimensionally growing after the accomplishment of entrapment until reaching equilibrium at 60 minutes. This can be interpreted by the time-consuming process of encapsulation of Cel molecules by the clench of LS chains.

Since the LCCs are dimensionally larger than Cel molecules, stronger electrostatic repulsion among particles was required to stabilize the solution of LCCs. Otherwise the LCCs would evolve into larger clusters, and eventually coacervate and precipitate. This would be fatal for the enzymatic catalysis of solid lignocellulosic substrate. Therefore, particular emphasis was made on the stability phase of LCCs at various molar ratios of LS to Cel. Figure 4 shows the size and zeta potential of LCCs in a broad range of LS/Cel, from approximately 1/105 to 1/1. As expected, the addition of LS to Cel solution led to the coacervation and precipitation at 52/104 of LS/Cel, where the size attained the maximum value of 2,765 nm. Moreover, the reverse process, referred to as redissolution [36], appeared upon further addition of LS as a result of the decrescent particle size and more negative surface potential. Given the size of the redissolved LCCs was about 105 nm, approximately the same as LS, the redissolved LCCs can be considered to be micelles with the flexible chains of LS carrying Cel molecules. Away from the main subject of the present study, the LS can also be used for enzyme separation because the coacervate of LCCs appeared at a very low molar ratio of LS to Cel, as shown in Figure 4. Furthermore, the separated Cel is supposed to be easy to use, since the further addition of LS makes it soluble again. The results reported here showed some similarity to the study of Lu et al. [37], who reported that the anionic polyelectrolyte in low concentration can promote nucleation when they are utilized as the precipitants for protein separation.

LS/Cel dependence of size and zeta potential for the LCCs in 50 mM buffer at pH 4.8 and 25°C. Various molar ratios of LS to Cel were realized by adding LS to 100 μL of Cel solution (1.5 mg/mL). The background image shows the mixtures with various molar ratios of LS to Cel at equilibrium. Cel, cellulase; LCC, lignosulfonate-cellulase complex; LS, lignosulfonate.

LCCs-induced reduction of nonproductive Cel binding to lignin

The elevated surface charge of LCCs is not only constructive to the stability of the solution of LCCs, but results in stronger electrostatic repulsion force between Cel and lignin, thus weakening the nonproductive binding of Cel to lignin. Consequently, the Cel binding is redistributed between lignin and cellulose during enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulose, which leads to the elevated catalytic selectivity. This mechanism is demonstrated in Figure 5. To verify the LCCs’ function of nonproductive binding reduction, the pure lignin (referred to as hydrolysis lignin residues) was made by repeated enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulosic substrate from SPORL-pretreated poplar. The Cel adsorption on the hydrolysis lignin residues was measured in the range of 0 to 1.4 mg/mL protein (Figure 6). The isotherms of Cel binding clearly showed the reduction of bound Cel as a result of LS application. To further quantify the nonproductive Cel binding, linear fitting was made to all experimental data collected to examine the maximum binding capacity Qs by using the Langmuir model equation (1). The value of Qs was reduced from 182.92 to 88.5 mg protein/g lignin as a result of LS application (Table 1), which suggested the significant role of LS in weakening the nonproductive binding. In fact, many approaches have been carried out with the purpose of elimination of nonproductive binding, including transgenic technology to reduce the lignin content [6], addition of additives (BSA, polyethylene glycol, and Tween 20) [38], and chemical modification of lignin [8]. The study by Eriksson et al. revealed that the non-ionic surfactants were most effective to nonproductive binding reduction in which the approximate reduction of enzyme adsorption was from 90% adsorbed enzyme to 80% with surfactant addition [12]. Similar results were also reported by Borjesson et al. by using poly(ethylene glycol) as additives [39]. The LS reported in the present study can be considered as additives that have a positive effect on nonproductive binding reduction. Since LS is the byproduct of pretreatment, this will undoubtedly promote the economical feasibility of biofuel production.

Schematic representation of LCCs-mediated Cel adsorption between lignin and cellulose. (A) Greater electrostatic repulsion between Cel and lignin is derived from the formation of LCCs that possess greater negative potential. (B) Binding of Cel to lignin in the case of enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulosic substrate without LS application. (C) Reduced Cel binding to lignin due to the LS application, which promotes the selectivity of enzymatic catalysis. Cel, cellulase; LCC, lignosulfonate-cellulase complex; LS, lignosulfonate.

Isotherms of Cel binding to lignin with and without LS application at 25°C and pH 5.2. The lignin was the hydrolysis lignin residuals from solid substrate SP-Po-A1B4 (see Table 3 for details about SP-Po-A1B4). Cel, cellulase; LS, lignosulfonate; SPORL, sulfite pretreatment to overcome recalcitrance of lignocellulose.

Enzymatic hydrolysis of SPORL-pretreated substrates with the application of SPORL pretreatment hydrolysate

After verification of the reduced nonproductive binding, the concern is extended to whether the biochemical activity of Cel is maintained in the resulting complexes; the answer to which is central to the molecular design of composite enzyme-polyelectrolyte systems, such as enzyme stabilizers and activators, as well as to the design of enzyme separation processes using water-soluble polyelectrolytes. To answer this question, LS was mixed with solid substrate SP-Po-A1B4, and then subjected to enzymatic saccharification. As expected, the terminal glucan conversion at 96 hours was elevated by 5% and 9% at pH 4.8 and pH 5.2, respectively (Figure 7). It can be deduced that the interactions between LS and Cel and the resultant complexes do not inhibit the enzyme activity. The enhancement of glucan conversion is considered to be the profit of the LS-induced reduction of nonproductive binding. For dilute acid pretreatment without LS production, the glucan conversion at the same Cel loading was much lower, in the range from approximately 21% to 49%, as shown in our previous work [40]. The greater gain of glucan conversion obtained at pH 5.2 can be ascribed to the pH-induced change of the surface potential of lignin, reported by Lan et al. [15]. The above results indicated that LCCs maintained full activity. Similar results were reported in a study on immobilization of β-glucosidase to spherical polyelectrolyte brushes (polystyrene sulfonic acid) [35]. Such protection of enzyme activity was ascribed to the reduction of thermal deactivation [41] and surface deactivation [42] when using surfactants as an activity protector. LS is a type of surfactant that is derived from sulfonation of lignin, and it is likely that LS protects the enzymes from deactivation during hydrolysis.

Besides LS, the SPORL hydrolysate also contains degradation products (Table 2). Some of the products are enzyme inhibitors, particularly furfural and HMF, which are regarded as the most toxic inhibitors present in pretreatment hydrolysate [43, 44]. To examine the combined effects of LS and inhibitors on glucan conversion of solid substrates, the SPORL hydrolysate was directly applied to enzymatic hydrolysis of solid substrates SP-Lp-A1B8 (SPORL-pretreated lodgepole pine) and SP-Po-A1B4 (SPORL-pretreated poplar). As shown in Figure 8, the striking increases of glucan conversion at 72 hours were observed with the addition of pretreatment hydrolysate, indicating that the benefits from LS outweigh the loss from inhibitors. Furthermore, the enhancement was almost linearly correlated to the addition of pretreatment hydrolysate. Considering the wood to liquor ratio of 1:3 (w/v) and the solid substrate yields of pretreatment (73.5% for poplar and 62.2% for lodgepole pine) in Table 2, the amounts of pretreatment hydrolysate (3.3 mL for SPORL-Po-A1B4 and 3.8 mL for SP-Lp-A1B8) in Figure 8 correspond to the amount of solid substrate used for enzymatic hydrolysis, namely 0.8 g. This means that the complete addition of pretreatment hydrolysate leads to the remarkable enhancement in glucan conversion; contrary to the conventional understanding that pretreatment hydrolysate inhibits the enzymatic hydrolysis unless detoxified. Specifically, the glucan conversion at 72 hours of enzymatic hydrolysis of solid substrate was increased by 25.9% (from 41.6% to 65.7%) and 31.8% (from 51.7% to 83.5%) for SPORL-Po-A1B4 and SP-Lp-A1B8, respectively, by the complete application of the corresponding pretreatment hydrolysate. This can be ascribed to the role of LCCs in nonproductive binding reduction, which is similar to the effect of BSA treatment on enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose in lignin containing substrates, as reported by Yang and Wyman [11]. Further, the role of LS in enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulose is quite similar to surfactant Tween 20, reported by Eriksson et al. [12]. Adding 5 g/L Tween 20 increased the glucan conversion of steam-pretreated spruce from 40% to 65%, while the adsorption of Cel was decreased from close to 90% to 65%. Compared to Tween 20 application [12], the increase of glucan conversion by LS addition was higher, particularly for substrate SP-Lp-A1B8.

Effect of the pretreatment hydrolysate on glucan conversion of solid substrate SP-Lp-A 1 B 8 and SP-Po-A 1 B 4 . (See Table 3 for details about SP-Lp-A1B8 and SP-Po-A1B4). The enzymatic hydrolysis was conducted at pH 4.8 with Cel dosage of 15 FPU/g glucan and β-glucosidase dosage of 22.5 CBU/g glucan for SP-Lp-A1B8 (0.8 g solid substrate), and 7.5 FPU/g glucan and β-glucosidase 11.25 CBU/g glucan for SP-Po-A1B4 (0.8 g solid substrate). Cel, cellulase; SPORL, sulfite pretreatment to overcome recalcitrance of lignocellulose.

Conclusions

This study revealed the formation of LCCs and their role in nonproductive binding mitigation during enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulose. LS, the byproduct of SPORL pretreatment, behaves as a polyelectrolyte to form LCCs with Cel. It was observed that the sulfonate acid groups on LS tended to associate to the oppositely charged groups on Cel, mainly the amino group. The results showed the complexation process was significantly affected by the ratio of LS to Cel. The elevated ratio of LS to Cel was constructive to the stability phase because of the increased surface potential and decreased particle size. Further, compared to Cel, LCCs were more negatively charged, and thereby had the ability of weakening the nonproductive binding of Cel to lignin due to the enlarged electrostatic repulsion. Isotherms of Cel adsorption showed the Cel binding by lignin was reduced from 182 mg/g to 88 mg/g by addition of LS. The LCCs-induced reduction of nonproductive binding was also reflected by the enhancement of glucan conversion with LS application. The experimental results showed that the glucan conversion of solid substrate of poplar and lodgepole pine was greatly increased by 25.9% and 31.8%, respectively, with the complete addition of the corresponding pretreatment hydrolysate.

Materials and methods

Materials

Novozymes Cellulosic Ethanol Enzyme Kit containing Cel (NS22086), β-glucosidase (NS22118), and hemicellulase (NS22002) were generously provided by Novozymes A/S (Bagsværd, Denmark). The molecular weight of Cel was assumed to be 50 kDa according to pertinent literature [45, 46]. Wood logs of 6-year-old poplar were harvested from natural stands growing in the south region of Shandong province, China (N35°42′5.03″, E118°42′40.62″), and 100-year-old lodgepole pine from the Arapaho Roosevelt National Forest, CO, USA (N40°24′20.12″, W105°35′37.54″).

SPORL pretreatment

SPORL pretreatment was carried out in a laboratory pulping digester, as described in our previous study [40]. Approximately 150 g of od wood chips were loaded. The procedures and conditions of SPORL pretreatment are listed in Table 3. After pretreatment, the wood chips were separated from the hydrolysate and then refined, as previously described [47]. The size-reduced solids were washed with deionized water to remove soluble degradation products for solid substrate production, that is, SP-Po-A1B4 and SP-Lp-A1B8. The Klason lignin content and polysaccharide content in the untreated wood and solid substrates (listed in Table 2) were determined according to the standard method of TAPPI T222 and literature [48], respectively. The majority of hemicellulose was removed by SPORL pretreatment as indicated by the changes of xylan and mannan content, which would facilitate the catalysis of cellulose. Most lignin remained in the solid substrate, but the sulfonation modification of lignin makes the solid substrate negatively charged, as suggested by the sulfonic acid groups and zeta potential in Table 2. The soluble degradation products in pretreatment hydrolysate listed in Table 2 were determined by HPLC according to the study of Luo et al. [49]. Clearly, the hydrolysate not only contains sugars and LS, but a lot of inhibitors in high concentration.

LS separation

The LS used in this study was isolated from the SPORL hydrolysate of poplar by membrane filtration according to the study of Madad et al. [50]. The poplar hydrolysate was filtered with 0.42 μm membrane. The obtained permeate was then subjected to diafiltration with 5 kDa MWCO membrane to remove impurities, such as salts and degradation products. Thereafter, the retentates inside the dialysis tube mainly contained LS and were used as pure LS. The molecule weight distribution of LS was measured by using size exclusion chromatography analysis (HPLC (LaChrom, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) equipped with a Superdex 200 HR 10/30 column (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK)). The results showed a wide molecular weight distribution, with a number average molecule weight (Mn) of 4,200 g/Mol and polydispersity of 1.53.

LCCs characterization by DLS analysis

The solution of Cel was filtered by 0.22 μm syringe membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) to remove microbial debris for sample preparation. Samples of Cel, LS, and LCCs were prepared at 50 mM sodium acetic buffer at a wide range of pH values, and 25°C for size and zeta potential measurements by DLS analyzer equipped with a laser Doppler microelectrophoresis (Zetasizer Nano ZS90, Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK). In addition, LCCs were prepared at various molar ratios of Cel to LS to investigate the colloidal size and zeta potential, and thereafter to estimate the stability phase of LCCs, which can be reflected by the formation of aggregates and precipitates.

Enzymatic hydrolysis

Enzymatic hydrolysis was conducted at 2% substrate solids (w/v) in pH 4.8 buffer solution on a shaker/incubator at 50°C and 200 rpm. Hydrolysate was sampled periodically for glucose concentration using HPLC (LC-20 T equipped with a column SCR-101C (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan)). Each data point was the average of two replicates. The average relative standard deviation was approximately 0.5%.

Preparation of hydrolysis lignin residues

The hydrolysis lignin residues were prepared enzymatically from solid substrates of poplar according to Lou et al. [51]. The enzymatic hydrolysis of substrate was conducted twice using 4.0 g SP-Po-A1B4 at solid loading of 2% (w/v), 50°C, and pH 5.2 for 48 hours, with a relatively high Cel dosage of 20 FPU/g substrate and hemicellulase supplement of 0.7 mL/g substrate. After enzymatic hydrolysis, the centrifuging at 10,000 rpm and lyophilization at −42°C were used to gain lignin residues, which was then grinded in a quartz mortar to produce a uniform particle size to meet the requirement of Cel adsorption.

Cel adsorption by hydrolysis lignin residues

Cel adsorption experiments were conducted at pH 5.2 and 25°C. The adsorption system consisted of 1.0 mL hydrolysis lignin residues solution (40 mg/mL), 0.5 mL Cel solution, and 0.5 mL buffer for control that was without LS addition or 0.5 mL LS solution (4.5 mg/mL). The initial concentrations of Cel were 0, 0.08, 0.4, 1.2, 1.6, and 2.4 mg/mL. After incubation for 1 hour, the free Cel in supernatant from centrifugal separation at 5,000 rpm for 5 minutes was measured according to Bradford protein assay [52]. The amount of the bound Cel on the hydrolysis lignin residues was calculated by subtracting the amount of the free Cel in the supernatant from the total amount of Cel applied initially. The Langmuir model equation (1) was used to fit the adsorption isotherm data. The maximum Cel adsorption capacity Qs (mg protein/g lignin) and the Cel adsorption equilibrium constant k (mL/mg protein) were determined accordingly:

in which Qe is the absorbed Cel at equilibrium (mg protein/g lignin) and Ce is the concentration of free Cel (mg protein/mL).

Abbreviations

- BSA:

-

Bovine serum albumin

- CBU:

-

Cellobiase unit

- Cel:

-

Cellulase

- DLS:

-

Dynamic light scattering

- FPL:

-

Forest Products Laboratory

- FPU:

-

Filter paper unit

- HMF:

-

Hydroxymethylfurfural

- HPLC:

-

High-performance liquid chromatography

- LCC:

-

Lignosulfonate-cellulase complex

- LS:

-

Lignosulfonate

- MW:

-

Molecular weight

- MWCO:

-

Molecular weight cut off

- od:

-

Oven dry

- PAMPS:

-

Polyacrylamidomethylpropyl sulfonate

- pI:

-

Isoelectric point

- SPORL:

-

Sulfite pretreatment to overcome recalcitrance of lignocellulose

- SSCombF:

-

Simultaneous saccharification and combined fermentation

- TAPPI:

-

Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper Industry

- USDA:

-

United States Department of Agriculture.

References

Sun Y, Cheng J: Hydrolysis of lignocellulosic materials for ethanol production: a review. Biorerource Technol 2002, 83: 1-11. 10.1016/S0960-8524(01)00212-7

Alvira P, Tomás-Pejó E, Ballesteros M, Negro M: Pretreatment technologies for an efficient bioethanol production process based on enzymatic hydrolysis: a review. Bioresource Technol 2010, 101: 4851-4861. 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.11.093

Pan X: Role of functional groups in lignin inhibition of enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose to glucose. J Biobased Mater Bioenergy 2008, 2: 25-32. 10.1166/jbmb.2008.005

Rahikainen J, Mikander S, Marjamaa K, Tamminen T, Lappas A, Viikari L, Kruus K: Inhibition of enzymatic hydrolysis by residual lignins from softwood—study of enzyme binding and inactivation on lignin‒rich surface. Biotechnol Bioeng 2011, 108: 2823-2834. 10.1002/bit.23242

Palmqvist E, Hahn-Hägerdal B: Fermentation of lignocellulosic hydrolysates. II: inhibitors and mechanisms of inhibition. Bioresour Technol 2000, 74: 25-33. 10.1016/S0960-8524(99)00161-3

Chen F, Dixon RA: Lignin modification improves fermentable sugar yields for biofuel production. Nat Biotechnol 2007, 25: 759-761. 10.1038/nbt1316

DeMartini JD, Pattathil S, Avci U, Szekalski K, Mazumder K, Hahn MG, Wyman CE: Application of monoclonal antibodies to investigate plant cell wall deconstruction for biofuels production. Energy Environ Sci 2011, 4: 4332-4339. 10.1039/c1ee02112e

Nakagame S, Chandra RP, Kadla JF, Saddler JN: Enhancing the enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass by increasing the carboxylic acid content of the associated lignin. Biotechnol Bioeng 2011, 108: 538-548. 10.1002/bit.22981

Fu D, Mazza G, Tamaki Y: Lignin extraction from straw by ionic liquids and enzymatic hydrolysis of the cellulosic residues. J Agric Food Chem 2010, 58: 2915-2922. 10.1021/jf903616y

Lee SH, Doherty TV, Linhardt RJ, Dordick JS: Ionic liquid‒mediated selective extraction of lignin from wood leading to enhanced enzymatic cellulose hydrolysis. Biotechnol Bioeng 2009, 102: 1368-1376. 10.1002/bit.22179

Yang B, Wyman CE: BSA treatment to enhance enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose in lignin containing substrates. Biotechnol Bioeng 2006, 94: 611-617. 10.1002/bit.20750

Eriksson T, Börjesson J, Tjerneld F: Mechanism of surfactant effect in enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulose. Enzyme Microb Technol 2002, 31: 353-364. 10.1016/S0141-0229(02)00134-5

Zhou H, Lou H, Yang D, Zhu JY, Qiu X: Lignosulfonate to enhance enzymatic saccharification of lignocelluloses: role of molecular weight and substrate lignin. Ind Eng Chem Res 2013, 52: 8464-8470. 10.1021/ie401085k

Zhu J, Pan X, Wang G, Gleisner R: Sulfite pretreatment (SPORL) for robust enzymatic saccharification of spruce and red pine. Bioresour Technol 2009, 100: 2411-2418. 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.10.057

Lan T, Lou H, Zhu J: Enzymatic saccharification of lignocelluloses should be conducted at elevated pH 5.2–6.2. BioEnergy Res 2013, 6: 476-485. 10.1007/s12155-012-9273-4

Del Rio LF, Chandra RP, Saddler JN: The effects of increasing swelling and anionic charges on the enzymatic hydrolysis of organosolv‒pretreated softwoods at low enzyme loadings. Biotechnol Bioeng 2011, 108: 1549-1558. 10.1002/bit.23090

Mattison KW, Dubin PL, Brittain IJ: Complex formation between bovine serum albumin and strong polyelectrolytes: effect of polymer charge density. J Phys Chem B 1998, 102: 3830-3836. 10.1021/jp980486u

Palmqvist E, Hahn-Hägerdal B: Fermentation of lignocellulosic hydrolysates. II: inhibitors and mechanisms of inhibition. Bioresour Technol 2000, 74: 25-33. 10.1016/S0960-8524(99)00161-3

Wang Z, Lan T, Zhu J: Lignosulfonate and elevated pH can enhance enzymatic saccharification of lignocelluloses. Biotechnol Biofuels 2013, 6: 9. 10.1186/1754-6834-6-9

Wold MS: Replication protein A: a heterotrimeric, single-stranded DNA-binding protein required for eukaryotic DNA metabolism. Annu Rev Biochem 1997, 66: 61-92. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.61

Ladisch MR (Ed): Protein Purification: From Molecular Mechanisms to Large-Scale Processes. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; 1990.

Dubin P, Gao J, Mattison K: Protein purification by selective phase separation with polyelectrolytes. Sep Purif Methods 1994, 23: 1-16. 10.1080/03602549408001288

Yf W, Gao JY, Dubin PL: Protein separation via polyelectrolyte coacervation: selectivity and efficiency. Biotechnol Prog 1996, 12: 356-362. 10.1021/bp960013+

Wang Y, Yu A, Caruso F: Nanoporous polyelectrolyte spheres prepared by sequentially coating sacrificial mesoporous silica spheres. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2005, 117: 2948-2952. 10.1002/ange.200462135

Wang Y, Caruso F: Mesoporous silica spheres as supports for enzyme immobilization and encapsulation. Chem Materials 2005, 17: 953-961. 10.1021/cm0483137

Caruso F, Trau D, Möhwald H, Renneberg R: Enzyme encapsulation in layer-by-layer engineered polymer multilayer capsules. Langmuir 2000, 16: 1485-1488. 10.1021/la991161n

Caruso F, Schüler C: Enzyme multilayers on colloid particles: assembly, stability, and enzymatic activity. Langmuir 2000, 16: 9595-9603. 10.1021/la000942h

Qiu Y, Park K: Environment-sensitive hydrogels for drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2001, 53: 321-339. 10.1016/S0169-409X(01)00203-4

George M, Abraham TE: Polyionic hydrocolloids for the intestinal delivery of protein drugs: alginate and chitosan—a review. J Control Release 2006, 114: 1-14. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.04.017

Becker NT, Lebo SE: Recovery of Proteins by Preciptation Using Lignosulfonates. WO 1998030580 A1. Mountain View, CA: Google Patents; 1998.

Cerbulis J: Precipitation of proteins from whey with bentonite and lignosulfonate. J Agric Food Chem 1978, 26: 806-809. 10.1021/jf60218a032

Windschitl P, Stern M: Evaluation of calcium lignosulfonate-treated soybean meal as a source of rumen protected protein for dairy cattle. J Dairy Sci 1988, 71: 3310-3322. 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(88)79936-1

McAllister T, Cheng K-J, Beauchemin K, Bailey D, Pickard M, Gilbert R: Use of lignosulfonate to decrease the rumen degradability of canola meal protein. Can J Anim Sci 1993, 73: 211-215. 10.4141/cjas93-022

Ertani A, Francioso O, Tugnoli V, Righi V, Nardi S: Effect of commercial lignosulfonate-humate on Zea mays L. metabolism. J Agric Food Chem 2011, 59: 11940-11948. 10.1021/jf202473e

Haupt B, Neumann T, Wittemann A, Ballauff M: Activity of enzymes immobilized in colloidal spherical polyelectrolyte brushes. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6: 948-955. 10.1021/bm0493584

Carlsson F, Malmsten M, Linse P: Protein-polyelectrolyte cluster formation and redissolution: a montecarlo study. J Am Chem Soc 2003, 125: 3140-3149. 10.1021/ja020935a

Lu J, Jiang X-L, Li Z, Rohani S, Ching C-B: Solubility of a lysozyme in polyelectrolyte aqueous solutions. J Chem Eng Data 2011, 56: 4808-4812. 10.1021/je200789w

Kumar R, Wyman CE: Effect of additives on the digestibility of corn stover solids following pretreatment by leading technologies. Biotechnol Bioeng 2009, 102: 1544-1557. 10.1002/bit.22203

Börjesson J, Engqvist M, Sipos B, Tjerneld F: Effect of poly (ethylene glycol) on enzymatic hydrolysis and adsorption of cellulase enzymes to pretreated lignocellulose. Enzyme Microb Technol 2007, 41: 186-195. 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2007.01.003

Wang Z, Zhu J, Zalesny RS Jr, Chen K: Ethanol production from poplar wood through enzymatic saccharification and fermentation by dilute acid and SPORL pretreatments. Fuel 2012, 95: 606-614.

Kaar WE, Holtzapple MT: Benefits from tween during enzymic hydrolysis of corn stover. Biotechnol Bioeng 1998, 59: 419-427. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19980820)59:4<419::AID-BIT4>3.0.CO;2-J

Kim M, Lee S, Ryu DD, Reese E: Surface deactivation of cellulase and its prevention. Enzyme Microb Technol 1982, 4: 99-103. 10.1016/0141-0229(82)90090-4

Jonsson LJ, Alriksson B, Nilvebrant N-O: Bioconversion of lignocellulose: inhibitors and detoxification. Biotechnol Biofuels 2013, 6: 16. 10.1186/1754-6834-6-16

Lynd LR: Overview and evaluation of fuel ethanol from cellulosic biomass: technology, economics, the environment, and policy. Annu Rev Energy Environ 1996, 21: 403-465. 10.1146/annurev.energy.21.1.403

Beldman G, Leeuwen MF, Rombouts FM, Voragen FG: The cellulase of Trichoderma viride. Purification, characterization and comparison of all detectable endoglucanases, exoglucanases and beta-glucosidases. Eur J Biochem 1985, 146: 301-308. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb08653.x

Vinzant T, Adney W, Decker S, Baker J, Kinter M, Sherman N, Fox J, Himmel M: Fingerprinting Trichoderma reesei hydrolases in a commercial cellulase preparation. In Twenty-Second Symposium on Biotechnology for Fuels and Chemicals. ABAB Symposium. New York City, NY: Humana Press; 2001:99-107.

Wang Z, Qin M, Fu Y, Yuan M, Chen Y, Tian M: Response of chemical profile and enzymatic digestibility to size reduction of woody biomass. Ind Crop Prod 2013, 50: 510-516.

Davis MW: A rapid modified method for compositional carbohydrate analysis of lignocellulosics by high pH anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC/PAD). J Wood Chem Technol 1998, 18: 235-252. 10.1080/02773819809349579

Luo X, Gleisner R, Tian S, Negron J, Zhu W, Horn E, Pan X, Zhu J: Evaluation of mountain beetle-infested lodgepole pine for cellulosic ethanol production by sulfite pretreatment to overcome recalcitrance of lignocellulose. Ind Eng Chem Res 2010, 49: 8258-8266. 10.1021/ie1003202

Madad N, Chebil L, Sanchez C, Ghoul M: Effect of molecular weight distribution on chemical, structural and physicochemical properties of sodium lignosulfonates. RASAYAN J Chem 2011, 4: 189-202.

Lou H, Zhu J, Lan TQ, Lai H, Qiu X: pH‒Induced lignin surface modification to reduce nonspecific cellulase binding and enhance enzymatic saccharification of lignocelluloses. ChemSusChem 2013, 6: 919-927. 10.1002/cssc.201200859

Bradford MM: A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 1976, 72: 248-254. 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the USDA FPL and South China University of Technology (State Key Laboratory of Pulp and Paper Open Fund number: 201240). This research was also sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China through the programs of 31300492 and BS2013NJ009. We are very grateful to JY Zhu at USDA FPL who provided critical advice and direction for the study. We also express our gratitude to colleagues ZC Li, DQ Wang, and CJ Wu for pretreatments, DLS analysis, and protein assay, separately.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ZW conducted most of the experiments and wrote the entire manuscript. Some initial research was directed by JZ at the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Products Laboratory (FPL). ZS conducted the glucose measurements. YF conducted the DLS analysis with the assistance from JJ and FY. MQ provided some suggestions on experiment design and manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Zhu, J., Fu, Y. et al. Lignosulfonate-mediated cellulase adsorption: enhanced enzymatic saccharification of lignocellulose through weakening nonproductive binding to lignin. Biotechnol Biofuels 6, 156 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1754-6834-6-156

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1754-6834-6-156