Abstract

Introduction

To date intracranial complication caused by tooth extractions are extremely rare. In particular parietal subdural empyema of odontogenic origin has not been described. A literature review is presented here to emphasize the extreme rarity of this clinical entity.

Case presentation

An 18-year-old Caucasian man with a history of dental extraction developed dysarthria, lethargy, purulent rhinorrhea, and fever. A computed tomography scan demonstrated extensive sinusitis involving maxillary sinus, anterior ethmoid and frontal sinus on the left side and a subdural fluid collection in the temporal-parietal site on the same side. He underwent vancomycin, metronidazole and meropenem therapy, and subsequently left maxillary antrostomy, and frontal and maxillary sinuses toilette by an open approach. The last clinical control done after 3 months showed a regression of all symptoms.

Conclusions

The occurrence of subdural empyema is an uncommon but possible sequela of a complicated tooth extraction. A multidisciplinary approach involving otolaryngologist, neurosurgeons, clinical microbiologist, and neuroradiologist is essential. Antibiotic therapy with surgical approach is the gold standard treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Suppurative intracranial infections (meningitis, intracranial abscess, subdural empyema and epidural abscess) are uncommon sequelae of paranasal sinusitis. In fact, the incidence of morbidity and mortality has been reported to range from 5 to 40% [1–4]; this is because the diagnosis is often unsuspected [5].

The literature on intracranial complications of sinusitis consists mainly of case reports with the exception of a few large series of hospitalized patients that present a rate of intracranial complications that varies from 3.7% to 47.6% [2, 6, 7].

However, paranasal sinuses disease is the presumed underlying cause of approximately 10% of intracranial suppuration [3, 7].

The frontal lobe is the most common location, and it is usually caused by chronic frontal sinusitis associated to nasal polyposis. Parietal lobe abscesses are usually associated with sphenoid rhinosinusitis, whereas there is rarely a correspondence to a temporal lobe abscess.

To date there is no evidence of an intracranial complication caused by tooth extraction. In fact, based on clinical presentation and microbiology, odontogenic paranasal sinus infections usually can be differentiated from those attributed to upper respiratory tract infections [8]; odontogenic paranasal sinus infections cause swelling in one or more of the deep fascial spaces of head and neck.

We report a rare and insidious case of parietal subdural empyema evolving over 2 weeks, secondary to dental extraction.

Case presentation

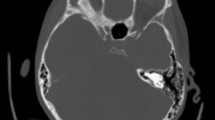

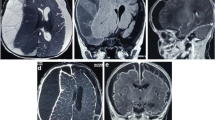

An 18-year-old Caucasian man was admitted to our Institution because of dysarthria, lethargy, purulent rhinorrhea, and fever for 2 days. His 6th dental element of the left side had been extracted 10 days earlier. His past medical history was unremarkable; he had a positive remote history for post-traumatic splenectomy. The first clinical examination revealed an increased body temperature of 37.6°C, heart rate of 82 beats per minute, blood pressure 150/64mmHg, and respiratory rate of 16 breaths/minute. He was orientated, his cranial nerves were intact, and his pupils were reactive, round and equal. His white cell count was 30,620 per μL with 80.2% of neutrophils and 6.6% lymphocytes. His hemoglobin was 11.1g/dL and C-reactive protein was 80mg/L. The levels of his chemistries were normal. His neurological examination confirmed the lethargic status and the dysarthria, whereas the conscious alertness was maintained. An anterior rhinoscopy displayed the presence of pus filling his whole nasal cavity, which was originating from the middle meatus. An examination of his oral cavity showed a fistula in the site of dental extraction communicating with the maxillary sinus. The findings of our physical examination of his head and neck were not significant; in particular there were no lymph nodes clinically evident.A computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast enhancement in emergency was performed and showed extensive sinusitis involving maxillary sinus, anterior ethmoid and frontal sinus on the left side (Figure 1). An interruption of sinus floor corresponding to alveolar process was evident (Figure 2). The orbital content was intact. A subdural fluid collection was present in the temporal-parietal site on the left side; a mass effect was evident with displacement of the middle line structures toward the opposite side (Figure 3).

He was admitted to our intensive care unit and underwent vancomycin and metronidazole therapy as standard protocol for sinusitis associated with intracranial complication. His condition deteriorated after 6 hours with right-side hemiparesis; after a further CT examination confirmed enlargement of the fluid collection, an emergent craniotomy was done to evacuate the subdural empyema. A cultural examination was attempted with the fluid evacuation and showed the massive presence of Bacteroides and a few colonies of alpha-hemolytic Streptococci, sensitive to meropenem that was added to therapy.

Two days after craniotomy, left maxillary antrostomy and frontal and maxillary sinuses toilette were performed by an open approach.

His fever decreased progressively in the next 3 days until his body temperature normalized. His cognitive conditions improved slowly and he was extubated on hospital day 10. Parenteral therapy and nutrition was continued for a further 12 days. The hemiparesis regressed progressively in 5 days. He was discharged 32 days after admission with normal alertness and gait, and a residual dysarthria; an antiepileptic therapy was prescribed with levetiracetam 1000mg per day. The last clinical control done after 3 months showed a regression of the dysarthria; a rhinoscopy revealed a good healing of the antrostomy, with normal drainage of his maxillary sinus, and the oral fistula appeared closed.

Discussion

Various etiologies are described in the literature as primum movens of subdural empyema including paranasal sinusitis (Table 1) [1–7, 9–22].

For the first time, we present an unusual case described in literature of a parietal subdural empyema secondary to acute odontogenic sinusitis, resulting from a tooth extraction (Table 2) [2, 3, 7, 11, 18, 20, 23]. According to Clayman et al., odontogenic sinusitis accounts for approximately 10% of cases of all maxillary sinusitis [2]. The microbiology of rhinosinusitis and odontogenic maxillary sinusitis are thought to be different; in fact it is universally accepted that Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis are commonly associated to upper respiratory tract sinusitis, whereas the typical odontogenic infection is a mixed aerobic/anaerobic infection, with a prevalence of anaerobic species (Streptococci, Bacteroides, Proteus, and coliform bacilli) [24]. Literature data confirm that more than 70% of rhinosinusitis intracranial complications are caused by Streptococci species, 15 to 20% by Staphylococcus aureus and 7% by Haemophilus species [20].

As our cultural examination revealed, the presence of Bacteroides in the subdural empyema was indicative of a relationship between such complication and the recent tooth extraction.

The roots of the maxillary premolar and molar teeth are situated below the sinus floor; in particular the second molars roots are the closest to the floor (mean distance of 1.97mm) [25]. These short distances explain how oroantral fistula may be responsible for the development of maxillary sinusitis that is generally characterized by a chronic course.Our case is remarkable for numerous reasons. He did not report a history of chronic sinusitis at the initial examination and, furthermore, there were no clinical or radiographic signs of maxillary sinusitis on the contralateral sinus. The time interval between acute sinusitis (purulent rhinorrhea and nasal obstruction) and symptoms of intracranial diseases, such as headache, altered mental status and lethargy, was of 2 days. It led us to believe that the sinusitis was of an acute type and was initiated by iatrogenic opening of an oroantral fistula (Figure 2).

The predisposition of young men to develop empyema has been explained by the high vascularity of the diploic system in this age group [2]. Moreover, in our patient the absence of the spleen was probably a cofactor of the rapid development of the intracranial complication. Finally, the presence of the air content into subdural space is suspicious of the odontogenic anaerobic microflora that was founded at cultural examination after empyema evacuation and that represents an extremely rare report.

Radiological evaluation should be done in all patients in whom subdural empyema is suspected. Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more sensitive in showing parenchymal abnormalities such as abscess [13], cranial CT is often the first neuroimaging done in emergency and gold standard for visualization of the paranasal sinuses and associated bony abnormalities. In early cases of subdural empyema, CT might not show a fluid collection [26–28], so consideration should be given to repeated CT imaging or MRI as the clinical scenario dictates. As shown by our case, CT evidenced the empyema as a thin, hypodense subdural lesion, with linear enhancement of the medial surface (Figure 3a and b). The grey-matter/white-matter interface is displaced inwardly. Mass effect is generally caused by edema and ischemia rather than mass effect from the abscess. The edema can cause effacement of the basilar cisterns and flattening of the cortical sulci [27]. The sinuses might appear opacified, with air-fluid levels and bony erosion evident in some cases [27], but a clinical report of air levels into subdural space is extremely rare [13].

According to our neurosurgeon’s diagnosis, he did not undergo lumbar puncture because it is hazardous and contraindicated in patients with subdural empyema, particularly if mass effect is present on CT [28]. In fact, the results are not specific and a neurological deterioration and transtentorial herniation after lumbar puncture are well described, and have led to death [1, 26, 28].

Various therapeutic measures include intravenous antibiotics, craniotomy drainage of intracranial abscess, and endoscopic and/or external drainage of affected sinuses. Once the diagnosis is made, the patient must undergo a combination of high-dose antimicrobial therapy that should be directed against the most common organisms and should include broad-spectrum activity against aerobic and anaerobic cocci and bacilli. Recommended empiric therapy is a third-generation cephalosporin plus metronidazole, which offers broad coverage and good cerebrospinal fluid and abscess penetration [20]. In our case, according to our neurosurgeon, he was given vancomycin and metronidazole and the antibiotic regimen was modified after the culture reports with the adding of meropenem, which is the gold standard therapy in cases of Bacteroides[24]. However, it is universally accepted that aggressive antibiotic therapy is not an alternative to surgical drainage that is recommended without delay. The goals of surgical intervention are both decompression of the brain and complete evacuation of purulence through craniotomy [29], and a definitive management of the infected sinuses should be done. The choice of surgical approach depends on the involved sinus and can include maxillary irrigation, external frontoethmoidectomy, sphenoid sinusotomy, antral washout, and frontal trephine. With the advent of endoscopy in treatment of sinusitis, the external approach has been less utilized [23]; according to some authors [3, 24, 25, 30, 31], we adopted the external approach for a complete curettage of the maxillary sinus.

Conclusions

The incidence of intracranial complications of sinusitis has decreased, but subdural empyemas remain an uncommon, but important, clinical condition with a variable incidence of morbidity and mortality. The occurrence of such disease is possible even in the case of a complicated tooth extraction that usually is responsive to standard medical and surgical treatments. The astute clinician should consider such complications in any patient presenting with fever, headache, and neurological deficits. A multidisciplinary approach involving otolaryngologist, neurosurgeons, clinical microbiologist, and neuroradiologist is essential. Effective management requires prompt diagnosis, surgical intervention in most cases, and appropriate antibiotics therapy.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging.

References

Jones NS, Walker JL, Bassi S, Jones T, Punt J: The intracranial complications of rhinosinusitis: can they be prevented?. Laryngoscope. 2002, 112: 59-63.

Clayman GL, Adams GL, Paugh DR, Koopmann CFJ: Intracranial complications of paranasal sinusitis: a combined institutional review. Laryngoscope. 1991, 101: 234-239.

Maniglia AJ, Goodwin WJ, Arnold JE, Ganz E: Intracranial abscesses secondary to nasal, sinus, and orbital infections in adults and children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989, 115: 424-429.

Gallagher RM, Gross CW, Phillips CD: Suppurative intracranial complications of sinusitis. Laryngoscope. 1998, 108: 1635-1642.

Moonis G, Granados A, Simon SL: Epidural hematoma as a complication of sphenoid sinusitis and epidural abscess. A case report and literature review. Clin Imaging. 2002, 26: 382-385.

Younis RT, Lazar RH, Anand VK: Intracranial complications of sinusitis: a 15-year review of 39 cases. Ear Nose Throat J. 2002, 81: 636-638.

Giannoni CM, Stewart MG, Alford EL: Intracranial complications of sinusitis. Laryngoscope. 1997, 107: 863-867.

Bentivegna D, Salvago P, Agrifoglio M, Ballacchino A, Ferrara S, Mucia M, Sireci F, Martines F: The linkage between upper respiratory tract infection and otitis media: evidence of the ‘united airways concept’. Acta Medica Mediterranea. 2012, 28: 287-290.

Lang EE, Curran AJ, Patil N, Walsh RM, Rawluk D, Walsh MA: Intracranial complications of acute frontal sinusitis. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2001, 26: 452-457.

Verbon A, Husni RN, Gordon SM, Lavertu P, Keys TF: Pott’s puffy tumor due to Haemophilus influenzae: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1996, 23: 1305-1307.

Chandy B, Todd J, Stucker FJ, Nathan CA: Pott’s puffy tumor and epidural abscess arising from dental sepsis: a case report. Laryngoscope. 2001, 111: 1732-1734.

Dispenza C, Saraniti C, Ferrara S, Martines F, Caramanna C, Salzano FA: Frontal sinus osteoma and palpebral abscess: case report. Rev Laryngol OtolRhinol (Bord). 2005, 126 (1): 49-51.

Younis RT, Anand V, Davidson B: The role of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in patients with sinusitis with complications. Laryngoscope. 2002, 112: 224-229.

Dolan RW, Chowdhury K: Diagnosis and treatment of intracranial complication of paranasal sinus infection. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995, 53: 1080-1087.

Nathoo N, Nadvi SS, van Dellen JR: Infratentorial empyema: analysis of 22 cases. Neurosurgery. 1997, 41: 1263-1269.

Akimura T, Ideguchi M, Kawakami N, Ito H: Brain abscess with fatal intraventricular rupture caused by asymptomatic paranasal sinusitis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1998, 255: 382-383.

Sahjpaul RL, Lee DH: Infratentorial subdural empyema, pituitary abscess, and septic cavernous sinus thrombophlebitis secondary to paranasal sinusitis: case report. Neurosurgery. 1999, 44: 864-867.

Lu CH, Chang WN, Lin YC, Tsai NW, Liliang PC, Su TM, Rau CS, Tsai YD, Liang CL, Chang CJ, Lee PY, Chang HW, Wu JJ: Bacterial brain abscess: microbiological features, epidemiological trends and therapeutic outcomes. QJM. 2002, 95 (8): 501-9.

Unlu HH, Aslan A, Goktan C, Egrilmez M: The intracranial complication of acute isolated sphenoid sinusitis. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2002, 29: 69-71.

Roche M, Humphreys H, Smyth E, Phillips J, Cunney R, McNamara E, O'Brien D, McArdle O: A twelve-year review of central nervous system bacterial abscesses; presentation and aetiology. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003, 9 (8): 803-9.

Fountas KN, Duwayri Y, Kapsalaki E, Dimopoulos VG, Johnston KW, Peppard SB, Robinson JS: Epidural intracranial abscess as a complication of frontal sinusitis: case report and review of the literature. South Med J. 2004, 97 (3): 279-82.

Martines F, Martinciglio G, Martines E, Bentivegna D: The role of atopy in otitis media with effusion among primary school children: audiological investigation. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010, 267: 1673-1678.

Gois CRT, Pereira CU, D’Avila JS, Melo VA: Intracranial complications of rhinosinusitis. Arq Int Otorrinolaringol. 2005, 9: 264-269.

Brook I: Sinusitis of odontogenic origin. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006, 135: 349-355.

Eberhardt JA, Torabinejad M, Christiansen EL: A computed tomographic study of the distances between the maxillary sinus floor and the apices of the maxillary posterior teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1992, 73: 345-346.

Weisberg L: Subdural empyema. Clinical and computed tomographic correlations. Arch Neurol. 1986, 43: 497-500.

Wong AM, Zimmerman RA, Simon EM, Pollock AN, Bilaniuk LT: Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of subdural empyemas in children. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004, 25 (6): 1016-1021.

Kaufman DM, Miller MH, Steigbigel NH: Subdural empyema: analysis of 17 recent cases and review of the literature. Medicine. 1975, 54: 485-498.

Sandu N, Sadr-Eshkevari P, Schaller BJ, Trigemino-Cardiac Reflex Examination Group (TCREG): Usefulness of case reports to improve medical knowledge regarding trigemino-cardiac reflex in skull base surgery. J Med Case Rep. 2011, 5: 149-doi:10.1186/1752-1947-5-149

Ali A, Kurien M, Mathews SS, Mathew J: Complications of acute infective rhinosinusitis: experience from a developing country. Singapore Med J. 2005, 46 (10): 540-4.

Betz CS, Issing W, Matschke J, Kremer A, Uhl E, Leunig A: Complications of acute frontal sinusitis: a retrospective study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2008, 265 (1): 63-72.

Acknowledgements

This study received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests in the preparation of this article.

Authors’ contributions

FM was the major contributor to writing the manuscript; PS, collection of data, manuscript preparation; SF, collection of data; MM, manuscript preparation, analysis; AG, analysis and collection of data; FS, manuscript preparation and analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Martines, F., Salvago, P., Ferrara, S. et al. Parietal subdural empyema as complication of acute odontogenic sinusitis: a case report. J Med Case Reports 8, 282 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1947-8-282

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1947-8-282