Abstract

Introduction

Spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage is a distinct clinical entity that can present as a rare life-threatening event characterized by sudden onset of bleeding into the retroperitoneal space, occurring in association with bleeding disorders, intratumoral bleeding, or ruptures of any retroperitoneal organ or aneurysm. The spontaneous form is the most infrequent retroperitoneal hemorrhage, causing significant morbidity and representing a diagnostic challenge.

Case presentation

We report the case of a patient with coronary artery disease who presented with transient ischemic attack, in whom anticoagulant therapy with heparin precipitated a massive spontaneous atraumatic retroperitoneal hemorrhage (with international normalized ratio 2.4), which was treated conservatively.

Conclusion

Delay in diagnosis is potentially fatal and high clinical suspicion remains crucial. Finally, it is a matter of controversy whether retroperitoneal hematomas should be surgically evacuated or conservatively treated and the final decision should be made after taking into consideration patient's general condition and the possibility of permanent femoral or sciatic neuropathy due to compression syndrome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hemorrhage is the most important complication of unfractionated heparin in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) treated with oral vitamin K antagonist (VKA) during hospitalization or among those receiving anticoagulants in terms of emergency or elective cardiac surgery [1, 2] or in the initial treatment of deep venous thrombosis [3, 4].

Analysis of the data presented by the European AF Trial Study Group [5] shows that as the international normalized ratio (INR) increased, there was an increase in the risk of major bleeding, such that at INR ≥ 5.0, the risk of bleeding increased 3.6-fold relative to INR ≤ 2. The optimal intensity of anticoagulation that achieved maximum therapeutic effect with minimum risk was determined to be at INR = 3.0. These data, along with recommendations from the recent American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) guidelines, indicate that the optimal intensity of anticoagulation for balancing efficacy in presenting stoke, while minimizing the risk of bleeding, is within the range INR = 2.0–3.0 (see [6]). Among outpatients receiving oral anticoagulants those with INR ≥ 6.0 face a significant risk of major hemorrhage [7].

Retroperitoneal hemorrhage is most frequently seen after femoral artery catheterization or pelvic and lumbar trauma [8–10]. In the absence of trauma, retroperitoneal hemorrhage most frequently results from a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm or bleeding from an underlying condition in the kidneys or adrenal glands. Spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage (SRH) denotes bleeding without any known inciting trauma or underlying retroperitoneal pathology. SRH is uncommon and is almost exclusively seen in association with anticoagulation states, coagulopathies and hemodialysis [11, 12].

A plethora of conditions have been used as a possible hypothesis of the pathophysiology of SRH. Unrecognized minor trauma in the microcirculation in the presence of coagulopathy has been suggested [13, 14].

The surgeons' quiver contains various types of approach to the treatment of this relatively uncommon complication such as conservative management, angiographic evaluation, percutaneous embolization or surgical intervention.

Case presentation

A 57-year-old Caucasian male was admitted to our hospital presenting with focal ischemic cerebral neurological deficit of acute onset. The patient had had an acute non-Q-wave myocardial infarction episode 11 years ago and post-infarct had undergone percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty: ramus circumflexus in 1995 and ramus diagonalis I in 1997. Eleven months before admission, an evaluation elsewhere had revealed persistent atrial fibrillation and since this evaluation the patient had been receiving Warfarin and had maintained INR = 2.0–2.5.

On the day of admission, examination of the patient revealed intense dizziness with diplopia, instability and complete left-sided homonymous hemianopsia. The findings suggested a transient ischemic attack involving the anterior circulation: carotid artery territory.

There was no personal or family history of coagulopathy or stroke, valvular heart disease trauma, chest pain or illicit intravenous drug usage. He smoked 20 cigarettes daily and consumed alcohol in moderation in the past.

The prothrombin was normal, INR = 2.4, the partial thromboplastin time was 45 seconds, the values for urea, nitrogen, creatinine, glucose, uric acid, bilirubin, phosphorus, electrolytes, creatinine kinase, lactate dehydrogenase, amylase and alkaline phosphatase were normal. An electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed atrial fibrillation at a rate of 110, with nonspecific ST-segment and T-wave abnormalities. A radiograph of the chest showed clear lungs and slight cardiac enlargement. A cardiac ultrasonographic examination showed no vegetations, intracardiac thrombus, segmental wall-motion abnormalities or intracardiac shunts. A test for the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was normal, as were tests for antinuclear antibodies, lupus anticoagulant and antiphospholipid antibody.

Computed tomography (CT) brain imaging was performed without the use of contrast material, but failed to indicate hemorrhage, infarct, abscess, tumor or cerebral metastasis. Heparin 20,000IE/24 hours intravenously and Metoprolol 100 mg by mouth were administered. Repeated physical examinations and ECGs showed no changes.

On the second hospital day the patient awoke with a slight neurologic deficit that gradually progressed in a stepwise fashion. Hemiplegia (upper left extremity and face were involved), hemianesthesia and Babinski sign contralateral to the hemiparesis were established. He had mild dysarthria, but his speech was fluent and his comprehension, repetition and naming abilities were intact. CT brain imaging was performed and no hemorrhagic transformation was found. Dipyridamole 200 mg/day, Aspirin 25 mg/day, Heparin 20,000IE/24 hours and Mannitol 20% solution (1 g/kg) were administered. Daily monitoring of ECG, vital signs, electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, urine output showed no changes.

On the fifth hospital day the patient noted the acute onset of pain in the lower right abdominal quadrant and lumbar region accompanied by mild nausea. The patient held the right hip in flexion and external rotation. Any attempt to straighten the leg aggravated the pain with radiation to the medial and anterior portions of the lower extremity Weakness of the right quadriceps femoris muscle, paresthesia over the anterior thigh and right flank were evident. The partial thromboplastin time was 43 seconds and INR = 2.4.

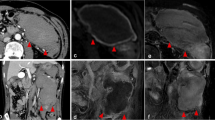

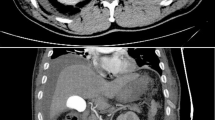

Hematocrit level fell as did hemoglobin (Table 1). CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the abdomen and the pelvis was obtained (Figures 1 and 2) and revealed extensive enlargement and heterogeneity of the right iliopsoas muscle as well as displacement of the right kidney. The high-attenuation component in the absence of intravenous contrast enhancement (Figure 3) is a finding that is usually consistent with the presence of a large retroperitoneal hematoma.

Transfusion of six units of packed red cells and the administration of two units of fresh frozen plasma was followed by fluid overload. The patient was treated conservatively and his condition promptly stabilized after the restoration of normal blood coagulation; however, he remained in the hospital for 38 days. Three months later he had signs of partial lateral paresis of the right quadriceps muscle and thigh adductors and, at 1-year follow-up, the only findings were suggestive of the previous transient ischemic attack involving the carotid artery territory; he had recovered completely from the femoral neuropathy.

Discussion

The large study of Sasson et al. [15] showed that patients who are receiving Heparin anticoagulation therapy, even in therapeutic doses, should be carefully monitored for the development of groin pain or leg weakness.

The most common symptoms are the acute onset, the severity and the persistence of the patient's pain in the lower abdominal quadrant, inguinal or lumbar region, and its radiation to the scrotum. Pain and paresthesia extend over the anterior, medial or lateral aspects of the lower extremities depending on the branches of the lumbar plexus that are involved. The most frequently involved nerve is the femoral nerve, the largest branch of the lumbar plexus which arises from the dorsal branches of L2, L3 and L4 ventral rami. It descends through the psoas major, emerging low on its lateral border and then passes between the psoas and iliacus, which makes the nerve vulnerable to traction injury from an underlying iliacus muscle hematoma [16, 17], deep to the iliac fascia, passing behind the inguinal ligament into the thigh.

The diagnosis of atraumatic retroperitoneal hemorrhage remains challenging even when high-resolution MRI and CT imaging are used, because a large number of benign or malignant lesions can mimic this condition [18, 19]. However, despite these limitations, MRI and CT imaging are superior to ultrasound and should be the preferred primary investigation [20–22].

The mainstay management currently consists of modification or cessation of anticoagulation therapy according to its clinical requirement, correction of the anticoagulation state, volume resuscitation and hemodynamic stabilization with adequate hematology and transfusion therapy and supportive measures [23]. Small hematomas with mild symptoms of neuropathy, without resultant obscuration, displacement or compression of normal retroperitoneal structures, without the need for multiple transfusions and without signs of infection may be treated conservatively.

On the other hand the effectiveness and safety of surgical intervention and evacuation of the hematoma should be considered as a potential strategy in uncontrollable hemodynamic collapse or when the nerve involved in the decompression might be effective in that the direct pressure and pressure-induced ischemic effects are reversible [24, 25]. The latter is limited by the inability to localize or control the bleeding vessel and the risk of worsening the bleeding by releasing the tamponade [26].

Conclusion

The rarity of this possible complication of the intravenous use of Heparin in patients with INR < 4.5 means that it remains a challenge for surgeons. We strongly suggest that, according to our experience, daily measurement of INR and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) in patient's receiving Heparin intravenously as an anticoagulation agent is of great importance. In deep vein thrombosis or acute myocardial infarction, the usual protocol requires injection of Heparin monitored by the prothrombin time, aPTT or both followed by long-term therapy with oral anticoagulants. As the half-life of Heparin is 3 hours, we suggest that aPTT to be measured 3 hours after Heparin administration or 1 hour before the next dose.

Some of the most important factors for the diagnosis are acute onset of pain, a dramatic change in the patient's clinical status and high clinical suspicion. CT and MRI remain the most powerful diagnostic tools. The complex challenge for the surgeon is the choice of clinical pathway in the management of this rare entity and this choices should only be made after taking two key points into consideration: (i) the patient's general condition; (ii) in the presence of permanent femoral or sciatic neuropathy due to a compression syndrome, hemodynamically unstable patients should be managed with an emergency laparotomy.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

References

Juergens CP, Semsarian C, Keech AC, Beller EM, Harris PJ: Hemorrhagic complications of intravenous heparin use. Am J Cardiol. 1997, 80: 150-154. 10.1016/S0002-9149(97)00309-3.

Mant MJ, O'Brien BD, Thong KL, Hammond GW, Birtwhistle RV, Grace MG: Haemorrhagic complications of heparin therapy. Lancet. 1977, 1: 1133-1135. 10.1016/S0140-6736(77)92388-1.

Leizorovicz A: Comparison of the efficacy and safety of low molecular weight heparins and unfractionated heparin in the initial treatment of deep venous thrombosis: an updated meta-analysis. Drugs. 1996, 52 (Suppl 7): 30-37.

Montoya JP, Pokala N, Melde SL: Retroperitoneal hematoma and enoxaparin. Ann Intern Med. 1999, 131: 796-797.

The European Atrial Fibrillation Trial Study Group: Optimal oral anticoagulant therapy in patients with nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation and recent cerebral ischemia. N Engl J Med. 1995, 333: 5-10. 10.1056/NEJM199507063330102.

Singer Daniel, Albers Gregory, Dalen James, Go Alan, Halperin Jonathan, Manning Warren: Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombotic Therapy. Chest. 2004, 126: 429S-456S. 10.1378/chest.126.3_suppl.429S.

Hylek EM, Chang YC, Skates SJ, Hughes RA, Singer DE: Prospective study of outcomes of ambulatory patients with excessive Warfarin anticoagulation. Arch Inter Med. 2000, 160: 1612-1617. 10.1001/archinte.160.11.1612.

Panetta T, Sclafani SJ, Goldstein AS, Phillips TF, Shaftan GW: Percutaneous Transcatheter embolization for massive bleeding from pelvic fractures. J Trauma. 1985, 25: 1021-1029.

Illescas FF, Baker ME, McCann R, Cohan RH, Silverman PM, Dunnick NR: CT evaluation of retroperitoneal hemorrhage associated with femoral arteriography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986, 146: 1289-1292.

Sclafani Salvatore, Florence Lauren, Phillips Thomas, Scalea Thomas, Glanz Sidney, Goldstein Alan, Duncan Albert, Shaftan Gerald: Lumbar arterial injury: radiologic diagnosis and management. Radiology. 1987, 165: 709-714.

Bhasin HK, Dana CL: Spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage in chronically hemodialyzed patients. Nephron. 1978, 22: 322-327.

Fernadez-Palazzi F, Hernandez SR, De Bosch NB, De Saez AR: Hematomas within the iliopsoas muscles in hemophilic patients: the Latin American experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996, 328: 19-24. 10.1097/00003086-199607000-00005.

McCort JJ: Intraperitoneal and retroperitoneal hemorrhage. Radiol Clin North Am. 1976, 14: 391-405.

Heim M, Horoszowski H, Seligsohn U, Martinowitz U, Strauss S: Iliopsoas hematoma – its detection, and treatment with special reference to hemophilia. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1982, 99 (3): 195-197. 10.1007/BF00379208.

Sasson Z, Mangat I, Peckham KA: Spontaneous iliopsoas hematoma in patients with unstable coronary syndromes receiving intravenous heparin in therapeutic doses. Can J Cardiol. 1996, 12: 490-494.

Nobel W, Marks SC, Kubik S: The anatomical basis for femoral nerve palsy following iliacus hematoma. J Neurosurg. 1980, 52: 533-540.

Susens GP, Hendrickson CG, Mulder MJ, Sams B: Femoral nerve entrapment secondary to a heparin hematoma. Ann Intern Med. 1968, 69: 575-

Nishimura H, Zhang Y, Ohkuma K, Uchida M, Hayabuchi N, Sun S: MR imaging of soft-tissue masses of the extraperitoneal spaces. Radiographics. 2001, 21: 1141-1154.

Lenchik L, Dovgan DJ, Kier R: CT of the iliopsoas compartment: value in differentiating tumor, abscess and hematoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994, 162 (1): 83-86.

Takebayashi S, Matsui K, Hidai H: Nontraumatic hemorrhage in abdomen and retroperitoneum-CT, sonographic and clinical findings. Nippon Igaku Hoshasen Gakkai Zasshi. 1990, 50: 1206-1214.

Pless T, Loertzer H, Brandt S, Radke J, Fornara P, Soukup J: Atraumatic retroperitoneal hemorrhage: interdisciplinary and differential diagnostic considerations based on a case report. Anaesthesiol Reanim. 2003, 28: 50-53.

Nazarian LN, Lev-Toaff AS, Spettell CM, Wechsler RJ: CT assessment of abdominal hemorrhage in coagulopathic patients: impact on clinical management. Abdom Imaging. 1999, 24: 246-249. 10.1007/s002619900489.

Sherer DM, Dayal AK, Schwartz BM, Oren R, Abufalia O: Extensive spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage: an unusual complication of heparin anticoagulation during pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Med. 1999, 8: 196-199. 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6661(199907/08)8:4<196::AID-MFM12>3.0.CO;2-Y.

Baker BH, Baker MS: Indications for exploring the retroperitoneal space. South Med J. 1980, 73: 969-970.

Topgul K, Uzun O, Anadol AZ, Gok A: Surgical management of enoxiparin- and/or warfarin- induced massive retroperitoneal bleeding: report of a case and review of the literature. South Med J. 2005, 98: 104-106. 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000145306.59008.4E.

Grimm MR, Vrahas MS, Thomas KA: Pressure volume characteristics of the intact and disrupted pelvic retroperitoneum. J Trauma. 1998, 44: 454-459.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

SID participated in the sequence alignment, in the design of the case report and drafted the manuscript. AB participated in the design of the case report. DP participated in the design of the case report and coordination. PP participated in the design of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Daliakopoulos, S.I., Bairaktaris, A., Papadimitriou, D. et al. Gigantic retroperitoneal hematoma as a complication of anticoagulation therapy with heparin in therapeutic doses: a case report. J Med Case Reports 2, 162 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1947-2-162

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1947-2-162