Abstract

Background

Cancer is a complex disease where molecular mechanism remains elusive. A systems approach is needed to integrate diverse biological information for the prognosis and therapy risk assessment using mechanistic approach to understand gene interactions in pathways and networks and functional attributes to unravel the biological behaviour of tumors.

Results

We weighted the functional attributes based on various functional properties observed between cancerous and non-cancerous genes reported from literature. This weighing schema was then encoded in a Boolean logic framework to rank differentially expressed genes. We have identified 17 genes to be differentially expressed from a total of 11,173 genes, where ten genes are reported to be down-regulated via epigenetic inactivation and seven genes are up-regulated. Here, we report that the overexpressed genes IRAK1, CHEK1 and BUB1 may play an important role in ovarian cancer. We also show that these 17 genes can be used to form an ovarian cancer signature, to distinguish normal from ovarian cancer subjects and that the set of three genes, CHEK1, AR, and LYN, can be used to classify good and poor prognostic tumors.

Conclusion

We provided a workflow using a Boolean logic schema for the identification of differentially expressed genes by integrating diverse biological information. This integrated approach resulted in the identification of genes as potential biomarkers in ovarian cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The development of gene expression microarrays more than a decade ago has led to the study of changes in the mRNA transcripts in disease-related tissues. These transcriptomic analyses from microarrays experiments served as the proxy for protein expression, and thereby revealed important properties of gene sets related to tissue-specificity [1, 2]. It has also facilitated the understanding of living cells at a systemic level by linking molecules to biological functions and thus bridging the genotype-to-phenotype gap via understanding the organisation of biological pathways [3] and the network of protein interactions [4]. In a seminal review, Hanahan and Weinberg [5] introduced six “hallmarks of cancer” (i.e. self-sufficient in growth signals, insensitivity to growth inhibition, evading apoptosis, tissue invasion and metastasis, sustained angiogenesis and limitless replicative potential), while a seventh hallmark (stemness) of cancer was concluded through gene expression analysis [6, 7]. The remarkable progress in cancer research suggests that hallmarks for cancer need to be extended further by including reprogramming of cellular metabolism to support neoplastic proliferation, acquired cellular properties to avoid immune destruction and genomic instability [8]. In recent years, researchers have made an effort to provide their microarray experiments for further studies through freely available public repositories such as Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) [9] and ArrayExpress [10].

The knowledge acquired over the years of research suggests that the cancer cells harbour genetic defects that alter the balance of cell proliferation and cell death [11]. This has led to the compilation of a cancer gene list, which has increased steadily over the last two decades. This disease is also highly variable with multiple heterogeneous genetic and epigenetic changes which makes it ideal to study cancer by integrating data from multiple experiments to understand its causes at the cellular level. Therefore, the identification and characterisation of susceptible genes associated with cancer is one of the greatest challenges in today’s biological and medical research. This challenge is partly due to the limitation of statistical methods on which a hypothesis about the value of a statistical parameter is made for the detection of genes effects and their interactions, as multiple biological components work in a concerted fashion. Moreover, biological systems are highly enriched with examples of combinatorial regulation and influence as molecules in signalling pathway and gene regulatory pathway jointly affect the cellular state [12]. In order to explore the combinatorial influence of multiple factors, Boolean-based logic is a popular approach for SNP association studies [13, 14] and in cancer [12, 15, 16].

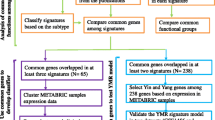

In this study, an integrated systems approach is used to identify diseased-associated genes that are either not reported or poorly characterized in the ovarian tumor samples. We have estimated weights for the functional attributes associated with the known cancer gene list. These weights are then combined using a Boolean logic schema, to calculate the probability-based rank associated with differentially and non-differentially expressed genes. Finally, we have mapped high scoring ranks of differentially expressed genes on the co-expression gene interaction network to validate disease-associated genes (Figure 1). This study suggests that of the 17 shortlisted genes flagged as significant, the overexpressed genes IRAK1, CHEK1 and BUB1 may play an important role in ovarian cancer. Using survival analysis, we also report that the set of three genes, CHEK1, AR, and LYN, can be used in the prognosis of ovarian tumors.

Methods

Identification of differentially expressed genes

We extracted and analysed TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) level 3 (Batch 9) ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma data from the Affymetrix platform [17]. TCGA gene expression data are normalised, annotated and validated for expression variation relevant to the tissue types and with the type of array platforms, thus increasing the robustness in analysing expression data. Rather than a fold-change, we have calculated the differential expression of each gene by considering the percentage of false prediction (pfp) ≤5% using the RankProd R package [18]. RankProd uses the rank product non-parametric method to indentify up/down-regulated genes under one condition against the other (in our case tumor vs. normal ovarian samples). This is based on the null hypothesis that the order of all items is random and the probability of finding a specific item among the top r of n items in a list is p = r/n. Multiplying these probability leads to the identification of the rank product , where r i is the rank of the item and n i is the total number of items in the ith list. The smaller the RP value, the smaller the probability that the observed placement of the item at the top of the list is due to chance.

Relevant functional attributes in the disease condition

Although microarrays measure the relative abundance of mRNA transcripts, their translated proteins are likely to be differentially present in diseased tissue. Moreover, the extent of differential protein concentration under the disease condition is quite difficult to estimate due to the heterogeneity of cells in the tumor sample. Therefore, we considered a Boolean combination of six proteins functional attributes for searching genes associated with ovarian cancer, where the causative effects are not additive but combinatorial as well as non-linear. These functional attributes are tissue specificity (TS), transcription factors (TFs), post-translation modifications (PTMs), protein kinases (PKs), secreted proteins (SPs) and whether the protein is a hub in the interactome, with node connectivity greater than four (i.e. node connectivity > = 5) along with the gene attribute of methylation (METH), in cancer vs. non-cancer associated genes.

We hope to capture the underlying enabling factors for cancer, by considering the above protein functional attributes. Large-scale data analysis supports the fact that disease genes are generally tissue-specific and are over-expressed in those tissues where changes in gene expression result in pathology [19]. TFs are DNA-binding proteins regulating gene expression and thereby control cell development, differentiation and growth [20] and their aberrant activity has been implicated in the cancer disease condition [21]. Oncogenic conversion of normal cells into cancerous cells involves changes in transcription factor, e.g. c-Fos component of TF c-Jun/JUN/AP-1 is crucial for the estrogen receptor α (ERα) mediated transcription in breast cancer [22]. PTMs of key regulatory or structural proteins are known to play an important role in the progression of cancer by activation of signalling pathways, enhanced proliferation and impaired cell division and death [23]. PTMs contributing to tumorigenesis include phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation, glycosylation, prolyl isomerisation, hydroxylation, oxidation, glutathionylation, sumolyation and ubiquitination. For example, clinical evidence suggests that phosphorylation, acetylation and sumolyation of ERα lead to prostate and breast cancer in humans [24]. PKs are important signalling molecules for maintaining normal tissue architecture and function, hence mutation in these genes are a common cause of human cancer (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/genetics/CGP/Kinases/) [25]. Recent developments in proteomic analyses suggest an increasingly large number of genes overexpressed in ovarian cancer, of which several encode secreted proteins [26]. For example, the high expression of prostasin [27] and osteopontin [28] are recorded in the serum of ovarian cancer patients. Highly connected proteins, i.e. hubs are shown to be essential in connecting diverse functional modules inside the cell [29]. Also, epigenetic inactivation of tumor-suppressor genes due to methylation is well known in carcinogenesis [30].

Data integration from multiple experiments

We extracted functional attributes via a text-mining approach. The cancer gene list was obtained by combining data from the Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics in Oncology and Haematology [31] and Futreal et al.[32], while information related to secreted proteins, tissue-specificity and protein’s post-translation modifications was obtained from HPRD [33]. Human protein kinases were extracted from the Human Kinome [34]. Transcription factors were extracted from TRED [35], HPRD [33] and TargetMine [36] databases. Gene methylations in ovarian samples were extracted from the studies reported by Mankoo et al.[37]. We considered the presence/absence of interaction in our high-confidence (HC) interactome dataset (detailed below) for differentially expressed genes, as biological pathways and networks of protein interactions are key paradigms to link molecules to biological functions. Therefore, interaction data were collected from BIND [38], BioGrid [39], DIP [40], HPRD [33], IntAct [41] and MINT [42] databases and merged into a single coherent interaction set after removing duplicate entries. Human protein interaction networks were further analysed to create a HC dataset by considering true interaction protein pairs as follow:

-

1.

If binary interaction among proteins is known to be present in more than one databases.

-

2.

Interacting protein pairs are true, if the interaction is verified from more than one detection method such as biochemical, biophysical, imaging techniques and/or protein complementation assay (PCA).

-

3.

If interacting protein pairs have known protein domain interaction mentioned in 3did [43] and iPfam [44] databases.

-

4.

PMIDs [45] were used as a proxy to support true interactions confirmed by more than one independent study.

These filters were used to define a HC protein interaction set to study the network properties of molecular functions and biological processes of interacting proteins. In this study, scoring schema for interactions were considered for those protein nodes with more than four interactions, as this is the empirical value of hubs suggested in gene co-expression stability in the analysis of protein interaction networks [46]. Therefore, we weighted such highly connected protein nodes encoded by the known cancerous genes.

Weighting schema for Boolean-based probability calculation

We used phi-correlation (r Φ ) as a measure of association between the functional attributes of the cancerous genes. This is one of the powerful methods to detect the association strength between two categorical data having binary values. Moreover, computationally it is related to the chi-square (χ2) value:

where N is the total number of genes.

Scoring schema on the weighted functional attributes for ranking genes

We used the Boolean algorithm proposed by Nagaraj and Reverter [15] for ranking the differentially expressed genes in ovarian samples, with our own set of Boolean variables representing relevant functional attributes in the disease condition. The particular combination across the seven Boolean variables i.e. functional attributes for a given differentially and non-differentially expressed genes, was decomposed into its root. For example, if a given gene has four known functional attributes, then 24 Boolean states are known to exist containing (24-1) roots, i.e. all possible combinations of Boolean states at the positions of known functional attributes, excluding the Boolean value with all zero status. The probability of each root is simply the average sum of all the weights associated with known functional attributes calculated via r Φ . These root probabilities are then used to rank the differentially and non-differentially expressed genes by summing up all the probability values associated with the individual roots.

Validation set

We retrieved the raw expression data for 153 ovarian tumor samples from the Gene Expression Omnibus entry GSE1349, containing samples in four tumor stages [9]. Raw expression values for each probe were transformed to log-scale with base 2. Probe IDs were converted to Entrez Gene IDs using AILUN [47]. For genes with multiple probes, the probes with the highest variance across the samples were used to describe the expression value for the genes. Probes with multiple or without Gene IDs were removed from the analysis. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated based on the co-expression values alone, to define the pairwise gene co-expressions. We have taken a Pearson’s coefficient > 0.5 to define a link between co-expressed genes in the gene expression network.

Network analysis of human signalling

We performed network analysis using the manually curated human signalling network [48]. The signalling network was pruned to contain associations between proteins alone and hence, small molecules were removed from the network, resulting in 1522 protein nodes and 4276 edges. The R package, igraph [49] was used for the network analysis. The Ingenuity Pathway Analysis system, (IPA, http://www.ingenuity.com) was further considered, to interpret the interaction of cancerous genes in humans.

Clinical characterization using survival analysis

For the high scoring Boolean-based differentially expressed genes, we performed Kaplan-Meier survival analysis using the Cox-Mantel log-rank test, implemented as an R package. The significance of these genes in the normal and tumor samples were evaluated from the Welch two sample t-test. A less conservative P- value < 0.1 was considered for the statistical significance of genes in the ovarian tumor sample classification. The clinical data were downloaded from the TCGA data portal.

Results and discussion

We used a systems biology approach to integrate diverse data resources as described in the Methods section. 2157 genes were identified to be differentially expressed in the tumor condition using the RankProd R package at a percentage of false positives: pfp ≤ 5%. The rank product method ensures ranking of expressed genes within each replicate (i.e. individual sample) and then computes the product of ranks across the replicates (i.e. multiple samples). Its distribution is then estimated by randomly permuting the observed ranks. Using this distribution, pfp is estimated. A cutoff of pfp ≤ 5% ensures that the observed data falls within two standard deviations of the mean, effectively translating to a p-value ≤ 0.05, expressing the probability that results at least as extreme as the above thresholds obtained in a sample were not due to chance. A total of 11,173 genes were considered in the TCGA expression set. This analysis suggested that 1353 and 804 genes were up-regulated and down-regulated respectively (Figure 2 and Additional file 1). An estimation of the weight was carried out via a simple observation of known functional attributes present between cancerous and non-cancerous genes. Table 1 lists the different functional attributes used as weights in this study. An odds-ratio analysis of differentially and non-differentially expressed genes showed no apparent differences (Additional file 2). This suggests that no single functional attribute can be selected alone in the classification of genes as a potential biomarker for the prognosis of the ovarian tumor condition. Moreover, cancer is well established as a disease model where the cellular system is abnormal leading to an uncontrolled cell division. Hence, a synergistic approach is needed to encapsulate the various functional attributes together for the understanding of the cancerous state. Figure 1 illustrates the workflow used for ranking genes. A Boolean framework for measuring unknown interactions between different biological entities and for the classification of genes in disease conditions have been reported by earlier studies [12, 15].

Differential gene expression in the TCGA ovarian dataset. Affymetrix TCGA gene expression dataset in ovarian tumor samples (class 1) vs. normal samples (class 2): A. Up-regulated genes and B. Down-regulated genes. RankProd analysis of differential gene expression at a percentage of false prediction (pfp) ≤ 5% is shown.

In this study, seven functional attributes, such as epigenetic inactivation (CpG gene methylation), protein post-translation modification, protein kinase, secreted protein, tissue-specificity, transcription factor and hub proteins in an interactome (protein node connectivity of 5 and above) were considered for the classification in the Boolean logic framework. We defined the Boolean logic for each gene, corresponding to the selected functional attributes (Table 2 and Additional file 2). These Boolean values were then decomposed to their roots to calculate the overall probability based on their functional attribute weights (detailed in the Methods section). Nagaraj and Reverter [15] have reported an average Boolean probability score of 0.219 (ranging from 0.002 to 0.687) for known cancer genes, compared to an average score of 0.081 (ranging from 0.000 to 0.589) for the other genes, indicating an average 2.71-fold enrichment using their Boolean logic, in their exhaustive study of 21,892 genes in colorectal cancer. In order to identify differential and non-differential gene expression as potential biomarkers with high confidence, we have set an empirical probability score greater than 0.5 as a cut-off, which is more than twice their reported average Boolean probability score. At this cut-off value, we were able to identify 17 differentially expressed genes (Table 2), whereas non-differential expression is noted for 48 genes (Additional file 3). In the TCGA expression dataset, we found seven (IRAK1, STC2, CDC7, CHEK1, KLK6, BUB1 and CHEK2) and ten (IGF1R, DAB2, IGFBP7, FOXL2, LCN2, CLU, LYN, PGR, AR and VIM) genes to be up-regulated and down-regulated, respectively, using RankProd analysis. In the validation dataset genes IGFBP7 and LCN2 are absent. Figure 3 compares the known functional attributes present in proteins encoded by differentially and non-differentially expressed genes. Moreover, we have verified the importance of these differentially expressed genes by mapping to their biological pathways (Additional file 4).

Functional attributes presented in various proteins encoded by differential/non-differential gene expression in the TCGA data. Histogram representing functional attributes such as Meth (methylation), PK (protein kinase), TF (transcription factor), TS (tissue specificity), PTM (post-translation modification), SP (secreted-proteins) and Hub (protein interactions where node connectivity > =5) presented in proteins encoded by differentially (in blue)/non-differentially (in pink) expressed genes.

Protein kinases

Protein kinases are important regulators of cell function and belong to a functionally diverse gene family. They affect the activity, localisation and overall function of other proteins by adding a phosphate group and thereby control the activity of cellular processes. Kinases are particularly important in signal transduction and co-ordination of complex functions such as cell cycle and pathological conditions. Identification of IRAK1 as a differentially expressed gene in ovarian cancer suggests its important role in this disease. It is a putative Ser/Thr kinase known to partially interact with transcription factor, NF-κB. Activation of NF-κB leads to cell proliferation, survival and migration [50]. Over-expression of this gene suggests indirect cell survival and proliferation in the ovarian tumor condition. Similarly, IGF1R is a receptor with tyrosine kinase activity, which binds an insulin-like growth factor. It is over-expressed in most malignant tissue, acting as an anti-apoptotic agent by enhancing cell survival [51, 52]. LYN is a non-receptor tyrosine kinase, phosphorylating caspase 8, rendering it inactive and thereby assisting apoptosis of the inflammatory cell [53]. In the absence of the normal expression of LYN, active caspase 8 may prevent the tumor cells from undergoing apoptosis.

Other important kinases in cell survival and proliferation during tumorigenesis are associated with key cell cycle proteins. CDC7 (cell-division cycle 7 homolog of S. cerevisiae) and BUB1 (budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 homolog of S. cerevisiae) encode protein kinases which induce G1/S transition and are involved with the spindle checkpoint function, respectively during cell mitosis. CDC7 is known to be overexpressed in the epithelial ovarian carcinoma, resulting in tumor progression, genomic instability and accelerated cell division [54]. On the other hand, BUB1 overexpression induces aneuploidy and tumor formation [55]. CHEK1 (checkpoint kinase 1) is an another important cell-cycle molecule of Ser/Thr protein kinase family mediating signals from ATM and ATR cell cycle proteins involved in the DNA damage response and associated with chromatin in the meiotic prophase I. The importance of this protein in tumor invasiveness has been suggested by researchers in lung, bladder, liver, prostate, gastric, brain, cervical and colorectal cancers and B-cell lymphoma [56–58]. CHEK2 (checkpoint kinase 2) is yet another important cell cycle protein which regulated key proteins during cell division. It interacted with BRCA1 (breast cancer 1) to restore survival in response to DNA damage with known association with endometrial cancer risk [59]. We observed overexpression of IRAK1, BUB1, CDC7, CHEK1 and CHEK2 genes in TCGA samples at a high Boolean probability score of 0.607561, together with the co-expression of other key cell-cycle molecules in an independent validation expression set GSE1349 suggesting their association in ovarian cancer (Figure 4 and Additional file 5). The presence of high probability up-regulated genes in the co-expression network (Pearson’s correlation coefficient > 0.5) is shown in Additional file 6. The co-expression network of downregulated genes is available from Additional file 7.

Co-expression of up-regulated genes. Schematic representation of up-regulated. Schematic representation genes: A. BUB1, B. CDC7, C. CHEK1, D. CHEK2, E. KLK6, F. IRAK1 and G. STC2. Edges are colour-coded to highlight the range of pearson’s correlation coefficient in co-expression network: black (> 0.7), slate grey (0.65 - 0.7), navy blue (0.60 - 0.65), slate blue (0.55- 0.60), dark green (0.50 – 0.55), dark olive green (0.45 - 0.05), yellow (0.40 – 0.45), indian red (0.35 -0.40), peru (0.30 -0.35). Refer to Additional file 5 for co-expressed neighbors and their associated co-expression Pearson’s correlation values.

Serine proteases

Serine proteases are proteolytic enzymes, hydrolysing the peptide bond of protein substrates via a nucleophilic serine residue in the active site [60]. Serine proteases play diverse roles in human health, from non-specific digestion to highly regulated functions like embryonic development, immune response and blood coagulation. Moreover, insufficient or excess protease activity can promote significant pathologies like cancer, inflammation, hemophilia, heart attack, stroke, pancreatitis and parasite infection [61]. We suggest the potential use of KLK6 (kallikrein-related peptidase 6) as a potential biomarker for ovarian cancer based on its high Boolean probability score (0.697808) (Figure 4). KLK6 is a serine protease with diverse functional roles inside the cell. It has been suggested that overexpression of this protein leads to the loss of cell-cell adhesion in skin cancer (melanoma) [62]. Moreover, a recent study reports the up-regulation of KLK6 in colon cancer and its use as a potential biomarker and therapeutic agent [63].

Secreted proteins

Secreted proteins are secreted from the cell into the extracellular space and have important biological regulatory roles with the potential for therapeutics. STC2 (Stanniocalcin 2) is a secreted homodimeric glycoprotein that is expressed in a variety of tissues. STC2 is known to promote the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and invasiveness in human ovarian cancer under inadequate oxygen supply to the tissue [64]. Our results show that STC2 is a significant up-regulated gene, promoting ovarian cancer. On the other hand, CLU (clusterin) and LCN2 (lipocalin 2) are down-regulated genes in our analysis. CLU encodes a protein which is secreted under stress conditions, that functions as a strong anti-migratory and anti-invasive agent by inducing the destruction of the actin cytoskeleton inside the cell [65]. The decreased expression of CLU thus promotes the cancerous disease condition. LCN2 encodes a 25 kDa secretory protein involved with iron-transportation and contributes to endometrial carcinoma [66]. Moreover, it is a key molecule in various signalling pathways (Additional file 4). Down-regulation of LCN2 due to epigenetic inactivation may lead to ovarian carcinoma.

Other types of proteins

We observed down-regulation of genes with high probability associated with phosphoproteins, transcription factors and receptors due to epigenetic inactivation. Phosphoprotein DAB2 is a mitogen-responsive agent, acting as tumor suppressor in normal ovaian epithelial cells and down-regulation of this gene modulates the TGF-β signalling pathway [67]. FOXL2 (forkhead box L2) encodes a transcription factor which helps in the normal development of ovarian tissue. IGFBP7 (insulin-like growth factor binding domain) is known as the tumor suppressor gene, leading to lung cancer due to the epigenetic inactivation [68]. PGR (progesterone receptor) encodes a protein playing a central role in the reproductive system by maintaining progesterone levels and ensuring normal pregnancy. AR (androgen receptor) encodes a protein which functions as a steroid hormone-activated transcription factor and has been shown to be involved in prostate cancer [69] as well as in ovarian cancer in association with p44[70]. VIM (vimentin) encodes a protein that is responsible for maintaining cell shape, integrity of the cytoplasm and stabilizing cytoskeleton interaction. Thus, the decreased expression of these genes could be indicative of ovarian cancer.

Relevance to cancer

We have mapped these 17 differentially expressed genes to gene ontology (GO) biological process terms collated from the GATHER [71] and the GENECARDS [72] databases as well as from the recent literature. The relevant GO terms linking these genes to the cancer hallmarks described by Hanahan and Weinberg [6] are presented in Table 3, with detailed information in Additional file 8 and Additional file 9. Each hallmark is associated with 1-13 of the 17 differentially expressed genes (mean = 5.7) while each gene maps to 1-6 hallmarks (mean = 2.8). While almost all the GO biological process terms could be unambiguously mapped to a cancer hallmark, the regulation of apoptotic process (GO:0042981) for LYN maps to both hallmark 3: active invasion and metastasis and hallmark 6: resist cell death and is shown in italics in Table 3. For STC2 and LCN2, the GeneCards biological process GO terms were augmented with literature search and the relevant references are provided in Additional file 9.

The complexity of cellular regulation is encapsulated in the signalling network. Moreover, signalling network also helps to understand the dynamics of oncogenic cross-talk by determining the sites at which oncogenic signals occur and through which oncogenic signals are transduced. Therefore, differentially and non-differentially expressed genes with high Boolean scores identified in the TCGA dataset (listed in Table 2 and Additional file 3, respectively) were mapped to the manually curated human signalling network [48], shown in Figure 5. Nine of the 17 differentially expressed genes and 32 of 48 non-differentially expressed genes could be mapped to the signalling network (Figure 5A). We have computed the importance of a node in the signalling network using betweenness centrality (the number of times a node acts as a bridge along the shortest path between two other nodes) and the influence of a node in the network using eigenvector centrality (relative scores to all nodes in the network with connections to high-scoring nodes receiving higher scored compared to low-ranking nodes). A plot of the two signalling network centrality measures (betweenness centrality and eigenvector centrality; Figure 5B) suggests the importance of the differentially expressed AR and the non-differentially expressed MAP3K7 (mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 7, involved in stress response) genes, which have ten shared interactions, from BioGraph [73], ranked 636 out of 18180 ‘Gene’ concepts (top 3.50%) in BioGraph’s knowledge base. Moreover, the nine differentially expressed genes (AR, CHEK1, CHEK2, PGR, VIM, LYN, IRAK1, IGF1R and DAB2) mapped to the signalling network were further identified using the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis system to visualize the interaction of these genes with the known oncogenes (Figure 6). The central role played by CHEK1 in the DNA damage response signalling network, has been confirmed by Dai and Grant [74], where CHEK2, CDC7 and BUB1 have also been identified from the 17 differentially expressed genes reported here.

Differentially and non-differentially expressed genes with high Boolean scores mapped to the human signalling network. A. Mapping of differentially expressed (with red labels) and non-differentially expressed (with blue labels) expressed genes from the TCGA data set on the human signalling network. Node size represents the residual value of linearly regressed betweenness and eigenvector centralities. B. Betweenness vs. eigenvector centrality plot of nine differentially expressed and 32 and non-differentially expressed genes identified in the human signalling network.

Clinical characterization

Table 2 lists 17 genes, of which seven are up-regulated and ten are down-regulated in ovarian cancer patients. The expression patterns of these genes suggest that the sum of the up-regulated gene expression values minus the sum of the down-regulated gene expression values should be maximized in ovarian cancer patients compared to controls without ovarian cancer (Additional file 10). Figure 7 shows that this is indeed the case for the 38 ovarian clinical samples and seven normal samples in this dataset and that this simple formula for the 17 genes identified here can be used to successfully distinguish between normal and ovarian cancer patients (p-value < 1.2E-06).

Ovarian cancer gene signature. Gene signature constructed from the expression values for each of genes given in Table 2, by substracting the sum of the down-regulated gene expression values from the sum of the up-regulated gene expression values. A. Individual scores for each of the normal and cancer patients. B. Mean signature values +/- (SEM) for the normal and cancer patients. Welch two sample t-test (t = -14.69, df = 8.45, p=2.621E-07).

Survival analysis was carried out to suggest if any of above 17 genes or their combinations, can be used in the classification and prognosis of ovarian cancer, to classify good and poor prognostic tumors. To demonstrate the survival analysis across the 38 ovarian clinical samples in this dataset, expression levels of each of the 17 genes were ranked from lowest to highest expression. Tumor samples associated with the lower 50% of the expression values for a given gene were labelled as “low-expression” for that gene; otherwise, they were labelled as a “high-expression” sample for that gene. Log-rank tests were then performed to suggest the difference between expected vs. observed survival outcomes for the low- and high-expression tumor samples for each of the genes. As there were only 38 ovarian tumor samples with clinical data, we chose the less stringent log-rank P-value of 0.1 and discovered three genes, CHEK1, AR and LYN exhibit a prognostic value, based on this cut-off level (see Figure 8).

Survival curves for ovarian cancer patients designated as being either high or low expression patients for genes CHEK1, AR and LYN . The lower of the two lines in each survival plot indicates patient with poor prognosis. The combinational plot CHEK1 + AR-LYN represents the sum of the expression values of CHEK1 and AR minus the expression of LYN. The p associated with each plot gives the p-value from the log-rank test for equality between the low and high expression groups from R’s Kaplan-Meier estimate of survival.

In Figure 8, the lower of the two curves in each of the four survival analysis plots indicates tumor samples associated with poor prognosis. Interestingly, though the survival curves associated with gene AR indicate poor prognosis is expected for tumor samples within the high expression range of AR, from Table 2 we note that AR is down-regulated in ovarian cancer. From Figure 8, it is seen that high expression for up-regulated CHEK1 and down-regulated AR and low expression for LYN leads to poor prognosis. The clinical data thus suggests a preference for limited down-regulation of AR. Therefore, combining the expression levels of these three genes as CHEK1+AR-LYN (Figure 8), then ranking this score from lowest to highest values and associating the patients into low and high expression groups, as before, gave greater significance in the prognostic outcome for classifying good and poor tumour outcomes than did the individual genes. Biologically, this combination represents increased cell cycle control, particularly for entry into mitosis (CHEK1), decreased expression of the androgen receptor (AR), whose expression levels have controversial reports as a favourable prognostic factor in epithelial ovarian cancer [75, 76] and moderately decreased expression of LYN, resulting in apoptosis of tumor cells.

Conclusions

We have statistically integrated gene expression and protein interaction data by combining weights in a Boolean framework to identify high scoring differentially expressed genes in ovarian tumor samples. This has resulted in the identification of important genes associated with critical biological processes. We identified 17 differentially expressed genes from a dataset of 11,173 genes, where seven and ten genes were up- and down-regulated, respectively with significant probability score in a Boolean logic schema. We report three genes (IRAK1, CHEK1 and BUB1) to be significant in ovarian tumor samples for the first time, to the best of our knowledge. A recent study on ovarian cancer supports our observation that the cell cycle proteins, CHEK1 and BUB1, are over-expressed and are important to the tumor condition, lending support to our observation [75]. Our results demonstrate the significance of multiple data types and knowledge-guided integration of diverse biological information to understand the molecular mechanisms associated in ovarian cancer and their application in the discovery of biomarkers. Network analysis of the human signalling pathways suggests the importance of the AR gene, which is down-regulated in ovarian tumor samples, leading to cancer. We also showed that the expression levels of the 17 genes discovered in this analysis can be used to distinguish between normal and ovarian cancer patients and that three genes, CHEK1, AR and LYN in combination can be used to classify good and poor prognostic tumors [77] from ovarian cancer patients.

References

Muller FJ, Laurent LC, Kostka D, Ulitsky I, Williams R, Lu C, Park IH, Rao MS, Shamir R, Schwartz PH, et al: Regulatory networks define phenotypic classes of human stem cell lines. Nature. 2008, 455 (7211): 401-405. 10.1038/nature07213.

Walker JR, Su AI, Self DW, Hogenesch JB, Lapp H, Maier R, Hoyer D, Bilbe G: Applications of a rat multiple tissue gene expression data set. Genome Res. 2004, 14 (4): 742-749. 10.1101/gr.2161804.

Magwene PM, Kim J: Estimating genomic coexpression networks using first-order conditional independence. Genome Biol. 2004, 5 (12): R100-10.1186/gb-2004-5-12-r100.

Kar G, Gursoy A, Keskin O: Human cancer protein-protein interaction network: a structural perspective. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009, 5 (12): e1000601-10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000601.

Hanahan D, Weinberg RA: The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000, 100 (1): 57-70. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81683-9.

Wong DJ, Segal E, Chang HY: Stemness, cancer and cancer stem cells. Cell Cycle. 2008, 7 (23): 3622-3624. 10.4161/cc.7.23.7104.

Glinsky GV: “Stemness” genomics law governs clinical behavior of human cancer: implications for decision making in disease management. J Clin Oncol. 2008, 26 (17): 2846-2853. 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.0266.

Hanahan D, Weinberg RA: Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011, 144 (5): 646-674. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013.

Barrett T, Troup DB, Wilhite SE, Ledoux P, Evangelista C, Kim IF, Tomashevsky M, Marshall KA, Phillippy KH, Sherman PM: NCBI GEO, et al: archive for functional genomics data sets--10 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39 (Database issue): D1005-D1010.

Bild AH, Yao G, Chang JT, Wang Q, Potti A, Chasse D, Joshi MB, Harpole D, Lancaster JM, Berchuck A, et al: Oncogenic pathway signatures in human cancers as a guide to targeted therapies. Nature. 2006, 439 (7074): 353-357. 10.1038/nature04296.

Zhang W, Laborde PM, Coombes KR, Berry DA, Hamilton SR: Cancer genomics: promises and complexities. Clin Cancer Res. 2001, 7 (8): 2159-2167.

Mukherjee S, Pelech S, Neve RM, Kuo WL, Ziyad S, Spellman PT, Gray JW, Speed TP: Sparse combinatorial inference with an application in cancer biology. Bioinformatics. 2009, 25 (2): 265-271. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn611.

Kooperberg C, Ruczinski I: Identifying interacting SNPs using Monte Carlo logic regression. Genet Epidemiol. 2005, 28 (2): 157-170. 10.1002/gepi.20042.

Schwender H, Ruczinski I: Logic regression and its extensions. Adv Genet. 2010, 72: 25-45.

Nagaraj SH, Reverter A: A Boolean-based systems biology approach to predict novel genes associated with cancer: Application to colorectal cancer. BMC Syst Biol. 2011, 5: 35-10.1186/1752-0509-5-35.

Ritchie MD, Hahn LW, Roodi N, Bailey LR, Dupont WD, Parl FF, Moore JH: Multifactor-dimensionality reduction reveals high-order interactions among estrogen-metabolism genes in sporadic breast cancer. Am J Hum Genet. 2001, 69 (1): 138-147. 10.1086/321276.

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network: Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011, 474 (7353): 609-615. 10.1038/nature10166.

Breitling R, Armengaud P, Amtmann A, Herzyk P: Rank products: a simple, yet powerful, new method to detect differentially regulated genes in replicated microarray experiments. FEBS Lett. 2004, 573 (1–3): 83-92.

Lage K, Hansen NT, Karlberg EO, Eklund AC, Roque FS, Donahoe PK, Szallasi Z, Jensen TS, Brunak S: A large-scale analysis of tissue-specific pathology and gene expression of human disease genes and complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008, 105 (52): 20870-20875. 10.1073/pnas.0810772105.

Latchman DS: Transcription-factor mutations and disease. N Engl J Med. 1996, 334 (1): 28-33. 10.1056/NEJM199601043340108.

Seth A, Watson DK: ETS transcription factors and their emerging roles in human cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2005, 41 (16): 2462-2478. 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.08.013.

Dahlman-Wright K, Qiao Y, Jonsson P, Gustafsson JA, Williams C, Zhao C: Interplay between AP-1 and estrogen receptor alpha in regulating gene expression and proliferation networks in breast cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2012, 33 (9): 1684-1691. 10.1093/carcin/bgs223.

Krueger KE, Srivastava S: Posttranslational protein modifications: current implications for cancer detection, prevention, and therapeutics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006, 5 (10): 1799-1810. 10.1074/mcp.R600009-MCP200.

Anbalagan M, Huderson B, Murphy L, Rowan BG: Post-translational modifications of nuclear receptors and human disease. Nucl Recept Signal. 2012, 10: e001-

Forbes SA, Bindal N, Bamford S, Cole C, Kok CY, Beare D, Jia M, Shepherd R, Leung K, Menzies A, et al: COSMIC: mining complete cancer genomes in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39 (Database issue): D945-D950.

Callesen AK, Mogensen O, Jensen AK, Kruse TA, Martinussen T, Jensen ON, Madsen JS: Reproducibility of mass spectrometry based protein profiles for diagnosis of ovarian cancer across clinical studies: A systematic review. J Proteomics. 2012, 75 (10): 2758-2772. 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.02.007.

Mok SC, Chao J, Skates S, Wong K, Yiu GK, Muto MG, Berkowitz RS, Cramer DW: Prostasin, a potential serum marker for ovarian cancer: identification through microarray technology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001, 93 (19): 1458-1464. 10.1093/jnci/93.19.1458.

Kim JH, Skates SJ, Uede T, Wong KK, Schorge JO, Feltmate CM, Berkowitz RS, Cramer DW, Mok SC: Osteopontin as a potential diagnostic biomarker for ovarian cancer. JAMA. 2002, 287 (13): 1671-1679. 10.1001/jama.287.13.1671.

Bandyopadhyay S, Chiang CY, Srivastava J, Gersten M, White S, Bell R, Kurschner C, Martin CH, Smoot M, Sahasrabudhe S, et al: A human MAP kinase interactome. Nat Methods. 2010, 7 (10): 801-805. 10.1038/nmeth.1506.

Hatada I, Fukasawa M, Kimura M, Morita S, Yamada K, Yoshikawa T, Yamanaka S, Endo C, Sakurada A, Sato M, et al: Genome-wide profiling of promoter methylation in human. Oncogene. 2006, 25 (21): 3059-3064. 10.1038/sj.onc.1209331.

Huret JL, Dessen P, Bernheim A: Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics in Oncology and Haematology, year 2003. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31 (1): 272-274. 10.1093/nar/gkg126.

Futreal PA, Coin L, Marshall M, Down T, Hubbard T, Wooster R, Rahman N, Stratton MR: A census of human cancer genes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004, 4 (3): 177-183. 10.1038/nrc1299.

Prasad TS, Kandasamy K, Pandey A: Human Protein Reference Database and Human Proteinpedia as discovery tools for systems biology. Methods Mol Biol. 2009, 577: 67-79. 10.1007/978-1-60761-232-2_6.

Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, Hunter T, Sudarsanam S: The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science. 2002, 298 (5600): 1912-1934. 10.1126/science.1075762.

Jiang C, Xuan Z, Zhao F, Zhang MQ: TRED: a transcriptional regulatory element database, new entries and other development. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35 (Database issue): D137-D140.

Chen YA, Tripathi LP, Mizuguchi K: TargetMine, an integrated data warehouse for candidate gene prioritisation and target discovery. PLoS One. 2011, 6 (3): e17844-10.1371/journal.pone.0017844.

Mankoo PK, Shen R, Schultz N, Levine DA, Sander C: Time to recurrence and survival in serous ovarian tumors predicted from integrated genomic profiles. PLoS One. 2011, 6 (11): e24709-10.1371/journal.pone.0024709.

Gilbert D: Biomolecular interaction network database. Brief Bioinform. 2005, 6 (2): 194-198. 10.1093/bib/6.2.194.

Stark C, Breitkreutz BJ, Chatr-Aryamontri A, Boucher L, Oughtred R, Livstone MS, Nixon J, Van Auken K, Wang X, Shi X, et al: The BioGRID Interaction Database: 2011 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39 (Database issue): D698-D704.

Salwinski L, Miller CS, Smith AJ, Pettit FK, Bowie JU, Eisenberg D: The Database of Interacting Proteins: 2004 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32 (Database issue): D449-D451.

Kerrien S, Alam-Faruque Y, Aranda B, Bancarz I, Bridge A, Derow C, Dimmer E, Feuermann M, Friedrichsen A, Huntley R, et al: IntAct--open source resource for molecular interaction data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35 (Database issue): D561-D565.

Ceol A, Chatr Aryamontri A, Licata L, Peluso D, Briganti L, Perfetto L, Castagnoli L, Cesareni G: MINT, the molecular interaction database: 2009 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38 (Database issue): D532-D539.

Stein A, Ceol A, Aloy P: 3did: identification and classification of domain-based interactions of known three-dimensional structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39 (Database issue): D718-D723.

Finn RD, Mistry J, Tate J, Coggill P, Heger A, Pollington JE, Gavin OL, Gunasekaran P, Ceric G, Forslund K, et al: The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38 (Database issue): D211-D222.

Hermjakob H, Montecchi-Palazzi L, Bader G, Wojcik J, Salwinski L, Ceol A, Moore S, Orchard S, Sarkans U, von Mering C, et al: The HUPO PSI’s molecular interaction format–a community standard for the representation of protein interaction data. Nat Biotechnol. 2004, 22 (2): 177-183. 10.1038/nbt926.

Patil A, Nakai K, Kinoshita K: Assessing the utility of gene co-expression stability in combination with correlation in the analysis of protein-protein interaction networks. BMC Genomics. 2011, 12 (Suppl 3): S19-10.1186/1471-2164-12-S3-S19.

Chen R, Li L, Butte AJ: AILUN: reannotating gene expression data automatically. Nat Methods. 2007, 4 (11): 879-10.1038/nmeth1107-879.

Cui Q, Ma Y, Jaramillo M, Bari H, Awan A, Yang S, Zhang S, Liu L, Lu M, O’Connor-McCourt M, et al: A map of human cancer signaling. Mol Syst Biol. 2007, 3: 152-

Csardi G, Nepusz T: The igraph software package for complex network research. InterJ Complex Syst. 2006, 1695-http://igraph.sf.net 2013 Feb 4

Papanikolaou V, Iliopoulos D, Dimou I, Dubos S, Kappas C, Kitsiou-Tzeli S, Tsezou A: Survivin regulation by HER2 through NF-kappaB and c-myc in irradiated breast cancer cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2011, 15 (7): 1542-1550. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01149.x.

Shiratsuchi I, Akagi Y, Kawahara A, Kinugasa T, Romeo K, Yoshida T, Ryu Y, Gotanda Y, Kage M, Shirouzu K: Expression of IGF-1 and IGF-1R and their relation to clinicopathological factors in colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2011, 31 (7): 2541-2545.

Mejia W, Castro C, Umana A, de Castro C, Riveros T, Sanchez-Gomez M: [Insulin-like growth factor receptor I signaling in a breast cancer cell line]. Biomedica. 2010, 30 (4): 551-558.

Jia SH, Parodo J, Kapus A, Rotstein OD, Marshall JC: Dynamic regulation of neutrophil survival through tyrosine phosphorylation or dephosphorylation of caspase-8. J Biol Chem. 2008, 283 (9): 5402-5413.

Kulkarni AA, Kingsbury SR, Tudzarova S, Hong HK, Loddo M, Rashid M, Rodriguez-Acebes S, Prevost AT, Ledermann JA, Stoeber K, et al: Cdc7 kinase is a predictor of survival and a novel therapeutic target in epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009, 15 (7): 2417-2425. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1276.

Ricke RM, Jeganathan KB, van Deursen JM: Bub1 overexpression induces aneuploidy and tumor formation through Aurora B kinase hyperactivation. J Cell Biol. 2011, 193 (6): 1049-1064. 10.1083/jcb.201012035.

Thorsen K, Schepeler T, Oster B, Rasmussen MH, Vang S, Wang K, Hansen KQ, Lamy P, Pedersen JS, Eller A, et al: Tumor-specific usage of alternative transcription start sites in colorectal cancer identified by genome-wide exon array analysis. BMC Genomics. 2011, 12: 505-10.1186/1471-2164-12-505.

Hoglund A, Nilsson LM, Muralidharan SV, Hasvold LA, Merta P, Rudelius M, Nikolova V, Keller U, Nilsson JA: Therapeutic implications for the induced levels of chk1 in myc-expressing cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2011, 17 (22): 7067-7079. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1198.

Indra D, Mitra S, Singh RK, Dutta S, Roy A, Mondal RK, Basu PS, Roychoudhury S, Panda CK: Inactivation of CHEK1 and EI24 are associated with the development of invasive cervical carcinoma: Clinical and prognostic implications. Int J Cancer. 2011, 129 (8): 1859-1871. 10.1002/ijc.25849.

O’Mara TA, Ferguson K, Fahey P, Marquart L, Yang HP, Lissowska J, Chanock S, Garcia-Closas M, Thompson DJ, Healey CS, et al: CHEK2, MGMT, SULT1E1 and SULT1A1 polymorphisms and endometrial cancer risk. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2011, 14 (4): 328-332. 10.1375/twin.14.4.328.

Di Cera E: Serine proteases. IUBMB Life. 2009, 61 (5): 510-515. 10.1002/iub.186.

Page MJ, Di Cera E: Serine peptidases: classification, structure and function. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008, 65 (7–8): 1220-1236.

Rezze GG, Fregnani JH, Duprat J, Landman G: Cell adhesion and communication proteins are differentially expressed in melanoma progression model. Hum Pathol. 2011, 42 (3): 409-418. 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.09.004.

Kim JT, Song EY, Chung KS, Kang MA, Kim JW, Kim SJ, Yeom YI, Kim JH, Kim KH, Lee HG: Up-regulation and clinical significance of serine protease kallikrein 6 in colon cancer. Cancer. 2011, 117 (12): 2608-2619. 10.1002/cncr.25841.

Law AY, Wong CK: Stanniocalcin-2 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and invasiveness in hypoxic human ovarian cancer cells. Exp Cell Res. 2010, 316 (20): 3425-3434. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.06.026.

Moretti RM, Mai S, Montagnani Marelli M, Rizzi F, Bettuzzi S, Limonta P: Molecular mechanisms of the antimetastatic activity of nuclear clusterin in prostate cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2011, 39 (1): 225-234.

Miyamoto T, Asaka R, Suzuki A, Takatsu A, Kashima H, Shiozawa T: Immunohistochemical detection of a specific receptor for lipocalin2 (solute carrier family 22 member 17, SLC22A17) and its prognostic significance in endometrial carcinoma. Exp Mol Pathol. 2011, 91 (2): 563-568. 10.1016/j.yexmp.2011.06.002.

Hannigan A, Smith P, Kalna G, Lo Nigro C, Orange C, O’Brien DI, Shah R, Syed N, Spender LC, Herrera B, et al: Epigenetic downregulation of human disabled homolog 2 switches TGF-beta from a tumor suppressor to a tumor promoter. J Clin Invest. 2010, 120 (8): 2842-2857. 10.1172/JCI36125.

Chen Y, Cui T, Knosel T, Yang L, Zoller K, Petersen I: IGFBP7 is a p53 target gene inactivated in human lung cancer by DNA hypermethylation. Lung Cancer. 2011, 73 (1): 38-44. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.10.015.

Sharma NL, Massie CE, Ramos-Montoya A, Zecchini V, Scott HE, Lamb AD, Macarthur S, Stark R, Warren AY, Mills IG, et al: The Androgen Receptor Induces a Distinct Transcriptional Program in Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer in Man. Cancer Cell. 2012

Lau KM, Mok SC, Ho SM: Expression of human estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta, progesterone receptor, and androgen receptor mRNA in normal and malignant ovarian epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999, 96 (10): 5722-5727. 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5722.

Chang JT, Nevins JR: GATHER: a systems approach to interpreting genomics signatures. Bioinformatics. 2006, 22 (23): 2926-33. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl483.

Stelzer G, Dalah I, Stein TI, Satanower Y, Rosen N, Nativ N, Oz-Levi D, Olender T, Belinky F, Bahir I, Krug H, Perco P, Mayer B, Kolker E, Safran M, Lancet D: In-silico human genomics with GeneCards. Hum Genomics. 2011, 5 (6): 709-17.

Liekens AM, De Knijf J, Daelemans W, Goethals B, De Rijk P, Del-Favero J: BioGraph: unsupervised biomedical knowledge discovery via automated hypothesis generation. Genome Biol. 2011, 12 (6): R57-10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r57.

Dai Y, Grant S: New insights into checkpoint kinase 1 in the DNA damage response signaling network. Clin Cancer Res. 2010, 16 (2): 376-383. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1029.

Nodin B, Zendehrokh N, Brändstedt J, Nilsson E, Manjer J, Brennan DJ, Jirström K: Increased androgen receptor expression in serous carcinoma of the ovary is associated with an improved survival. J Ovarian Res. 2010, 3: 14-10.1186/1757-2215-3-14.

Zhang S, Liu CC, Li W, Shen H, Laird PW, Zhou XJ: Discovery of multi-dimensional modules by integrative analysis of cancer genomic data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40 (19): 9379-9391. 10.1093/nar/gks725.

Li J, Lenferink AE, Deng Y, Collins C, Cui Q, Purisima EO, O’Connor-McCourt MD, Wang E: Identification of high-quality cancer prognostic markers and metastasis network modules. Nat Commun. 2010, 1: 34-

Acknowledgements

We thank to Drs. Nagaraj and Reverter, CSIRO for providing a copy of the Boolean algorithm. This research was supported by the Macquarie University Research Scholarship (MQRES) to GK and the ARC Centre of Excellence in Bioinformatics grant (CE0348221) to SR.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the experiment: GK. Data collected and analysed: GK, SR. EB performed the clinical classification. Manuscript has been written and finalised by GK, EB and SR. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12918_2012_1056_MOESM4_ESM.pdf

Additional file 4: Statistically significant pathway analysis from the NCI-nature PID (Pathway Interaction Database) of the 17 differentially expressed genes in various biological pathways.(PDF 153 KB)

12918_2012_1056_MOESM5_ESM.pdf

Additional file 5:High confidence up/down-regulated genes identified in the Boolean framework with their co-expressed neighbors.(PDF 71 KB)

12918_2012_1056_MOESM6_ESM.pdf

Additional file 6:Schematic representation of co-expressed genes with significant Boolean values. Edges are colour-coded to highlight the range of pearson’s correlation coefficient in co-expression network: black (> 0.7), slate grey (0.65 - 0.7), navy blue (0.60 - 0.65), slate blue ( 0.55- 0.60), dark green (0.50 – 0.55), dark olive green (0.45 – 0.50 ). Yellow (0.40 -0.45), indian red (0.35 -0.40 ) and peru (0.30 - 0.35). (PDF 2 MB)

12918_2012_1056_MOESM8_ESM.pdf

Additional file 8: Relevant GO biological process characterization from GeneCards [67] for the 17 differentially expressed genes, mapped to cancer hallmarks (HM) in Table 3. (PDF 99 KB)

12918_2012_1056_MOESM9_ESM.pdf

Additional file 9:Gene expression data for the 17 genes identified in this study across 45 (38 tumor + 7 normal) samples.(PDF 177 KB)

12918_2012_1056_MOESM10_ESM.xls

Additional file 10:Gene expression data for the 17 genes identified in this study across 45 (38 tumor + 7 normal) samples.(XLS 48 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kumar, G., Breen, E.J. & Ranganathan, S. Identification of ovarian cancer associated genes using an integrated approach in a Boolean framework. BMC Syst Biol 7, 12 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-0509-7-12

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-0509-7-12