Abstract

Background

On-farm biosecurity is an important part of disease prevention and control, this applies to live animal contacts as well as indirect contacts e.g. via professionals visiting farms in their work. The objectives of this study were to investigate how professionals visiting animal farms in Sweden in their daily work perceive the on-farm conditions for biosecurity, the factors that influence their own biosecurity routines and what they describe as obstacles for biosecurity. Suggestions for improvements were also asked for. Questionnaires were distributed to professionals visiting farms in their daily work; veterinarians, livestock hauliers, artificial insemination technicians, animal welfare inspectors and cattle hoof trimmers. The sample was a convenience sample, based on accessibility to registers or collaboration with organisations distributing the questionnaire. Respondents were asked about the availability of certain biosecurity conditions related to farm visits, e.g. if facilities for hand washing were available, how important different factors were for their own routines and, through open ended questions, to describe obstacles and suggestions for improvement.

Results

After data cleaning, there were responses from 368 persons. There was a difference in the proportion of visited farms reported to have certain biosecurity measures in place related to animal species present on the farm. In general, visited pig farms had a higher proportion of biosecurity measures in place, whereas the conditions were poorer on sheep and goat farms and horse farms. There were also differences between the visitor categories; the perceived conditions for biosecurity varied between the groups, e.g. livestock hauliers did not have access to hand washing facilities as often as veterinarians did. In all groups, a majority of the respondents perceived obstacles for on-farm biosecurity, among veterinarians 66% perceived that there were obstacles. Many of the reported obstacles related to the very basics of biosecurity, such as access to soap and water. Responsibility was identified to be a key issue; while some farmers expect visitors to take responsibility for keeping up biosecurity they do not provide the adequate on-farm conditions.

Conclusions

Many of the respondents reported obstacles for keeping good biosecurity related to on-farm conditions. There was a gap when it came to responsibility which needs to be clarified. Visitors need to take responsibility for avoiding spread of disease, while farmers need to assume responsibility for providing adequate conditions for on-farm biosecurity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Indirect contacts via visitors can play a role in the spread of both endemic and exotic diseases. Adequate biosecurity routines can minimize the risk of such spread, e.g. using clean boots and protective clothing and cleaning equipment between farms. Correspondingly, a lack of biosecurity can contribute to the spread of disease [1–6].

The importance of farm biosecurity has been highlighted during the last decade; within the European Union (EU) the proposal for a new animal health law emphasises biosecurity [7] and a number of studies with focus on-farm biosecurity have been published [3, 8–20]. Specifically related to farm visits and biosecurity for visitors, Racicot and co-authors have in a series of studies analyzed biosecurity errors while entering farms and factors affecting compliance with routines, e.g. personality traits and education [21–23].

In a previous study conducted in Sweden [24], disparities were found in biosecurity routines between farmers with different species and different herd sizes. The farmers also reported a difference in the biosecurity routines applied by different categories of professional visitors coming to their farms, for example livestock hauliers, veterinarians and inspectors. Some farmers reported that they had different requirements for biosecurity depending on type of visitor. Moreover, some farmers reported that they did not consider biosecurity necessary unless there were current outbreaks of exotic diseases in the country. When working with outbreak investigations, the authors have experienced that professional visitors sometimes adapt their routines depending on the farmers’ requirements, the same person can thus have very different routines in different farms. This interaction between the farmer and the visitor is part of the complexity related to the on-farm biosecurity applied by visitors. Several different factors could influence the intended behaviour of the visitor, such as the requirements from their own organization and their own will not to spread disease. But regardless of the visitors’ own intentions, the practical and physical conditions provided on the farms, as well as requirements, or lack thereof, from the farmers, will probably affect what is actually done on each farm. Practical obstacles can impair the intended behaviour. If the visitor does not have access to running water while on the farm, washing the boots before leaving will be difficult. In a Canadian study it was shown that design of the hygiene barrier affected the number of biosecurity errors made by visitors [22].

Although many diseases are species specific, this does not apply to all diseases. Some visitors, e.g. veterinarians, often visit many different categories of farms and could potentially spread disease between different species or different categories of the population. If the routines for biosecurity are inferior in one type of species, this could thus impact spread of disease to other species. Some of the diseases are also zoonotic; several studies have identified a higher prevalence of zoonotic diseases among veterinarians, and concern among veterinarians for contracting zoonotic infections has also been investigated [25–28].

In Sweden, as well as in other parts of the EU, several projects are currently underway to improve on-farm biosecurity routines, decrease the risk of spread of endemic livestock diseases and decrease the risk of outbreaks of exotic diseases. The proposal for a new EU Animal Health Law puts more responsibility for disease prevention on the farmers and, consequently, a high level of on-farm biosecurity will be required when the regulation comes into force [7].

The objectives of this study were to investigate how professionals visiting farms with animals in Sweden in their daily work perceive the on-farm conditions for biosecurity, the factors that influence their own biosecurity routines and what they describe as obstacles for biosecurity, and to collect suggestions for improvements. The aim is to use the information as a basis for future work in improving on-farm biosecurity and biosecurity among professional visitors.

Methods

Sample and distribution of questionnaire

Data in this study were gathered through questionnaires sent to five categories of professionals that regularly visit farms in their work. These were; veterinarians, livestock hauliers, artificial insemination (AI) technicians, animal welfare inspectors and cattle hoof trimmers. This sample was a convenience sample of groups where some kind of contact information or distribution channel was found. The chosen categories were either included in an accessible official register (livestock hauliers), or were part of organizations that were willing to distribute the questionnaire among their employees or members (veterinarians, AI-technicians, animal welfare inspectors), or had contact information available on websites (hoof trimmers). For this reason the exact number of persons receiving the questionnaires within each category is not known. For veterinarians, e-mail questionnaires were distributed by the two Swedish veterinary unions (without indicating the exact number of recipients, one of the unions reported they sent to all members and the other one to members of the sections for livestock and horse practitioners). Livestock hauliers were identified through an official register held by the Swedish Board of Agriculture and were sent the questionnaire either via e-mail (n = 104), in paper format (n = 40), or both paper and e-mail (n = 35) depending on the data received from the register; not all livestock hauliers had e-mail addresses. Three AI companies, one national and two regional, distributed the electronic version of the questionnaire among their employees (the exact number of recipients is not known). Animal welfare inspectors in Sweden work in the County Administrative Boards, and were contacted through the network of the heads of animal welfare in these authorities. The questionnaire was distributed within their network and redistributed at regional level by their contact points (exact number of recipients is therefore not known). Cattle hoof trimmers were identified through a cattle hoof trimmers organization webpage and, after a search of addresses using an internet search engine, questionnaires were sent to all e-mail addresses obtained (n = 57). The questionnaires were distributed between May and December 2012. An invitation letter was attached to the questionnaire which explained the background of the study, clarified that answers would be treated anonymously and encouraged participation. Reminders were sent to hoof trimmers and some of the livestock hauliers for which there was direct access to the e-mail addresses. Since other groups received the questionnaire through their organisations, sometimes forwarded in several steps, reminders were not sent to these groups.

The first section of questions related to the on-farm conditions. Respondents were asked to give the proportions of farms they visit that have; hygiene barrier, protective clothing for visitors, hand-washing facilities, hand disinfection, and requirements as regards to the use of protective clothing. These questions were split by species present on the farms (cattle, pigs, sheep/goats, horses) and respondents were asked to respond only for the farms that they normally visit in their daily work. Livestock hauliers were also asked how often they needed to enter animal buildings. The second part of the questions related to the visitors’ own routines; how important different factors were for their routines, and the proportion of visits when they applied different routines. The third, and last, part consisted of open ended questions. Respondents were asked if there were any diseases that they in their profession were afraid to spread between farms or contract themselves. Finally they were asked about obstacles for biosecurity and factors for improving biosecurity, both on farm level and within their own profession. The questionnaire also included background questions on profession, age, number of farms visited per week. The questionnaire is available as Additional file 1 (in English) and Additional file 2 (in Swedish). Before sending the questionnaire, a pilot version was tested on 14 veterinarians working in the National Veterinary Institute. The group was a mixture of persons with recent experience of working in the field and visiting farms on a daily basis, with expertise in biosecurity or with experience in questionnaire design. Data from the paper questionnaires were entered manually into the electronic version of the questionnaire, data entry was checked for consistency.

Analysis

The data were checked and cleaned; data from respondents that were not part of the intended study population were dropped. Descriptive statistics were obtained for all closed questions, both total and by categories of visitors. The responses to all open questions were read separately by the two authors, who created different categories representing the different types of responses. These categories were thereafter compared and merged into a single list by the two researchers. Each response was then assigned into one or more of the categories, this was also done separately by the two authors and the results were then checked for consistency. Whenever there was a discrepancy, this was discussed and the response was assigned to one of the categories. Finally, the frequency of the different response categories was calculated. Some replies were combined, for example, ‘MRSA’ (Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus) were combined with ‘multiresistant bacteria’, thus anyone replying both ‘MRSA’ and ‘multiresistant bacteria’ contributed only once to ‘multiresistant bacteria or MRSA’.

Software used

The questionnaire was designed and administered using the web survey software Easyresearch (QuestBack International HQ, Oslo, Norway). Data were analysed using STATA 11.2 (Stata Co., College Station, Texas, USA), graphs were drawn using Microsoft Office Excel 2007 (Microsoft Co., Redmond, USA).

Results

Response rate

The numbers of respondents (to the entire or part of the questionnaire) after data cleaning were; 188 veterinarians, 82 animal welfare inspectors, 59 AI-technicians, 28 livestock hauliers and 11 cattle hoof trimmers, in total 368. Seven respondents were dropped during data cleaning because they either did not visit farms, worked abroad or belonged to a profession that was not included in the sample. The age of the respondents was as follows; 20% were 20–35 years, 35% 36–50, 41% 51–65 and 4% >66 years. The age varied between the groups; 63% of the AI-technicians, 52% of the hauliers and 51% of veterinarians were above 50 years of age, while only 36% of the hoof trimmers and 17% of the inspectors were above 50 years of age. Since the sample was a convenience sample and data collection relied on the collaboration with organizations and their willingness to distribute the questionnaire, the number of persons that received the questionnaire within each category for veterinarians, AI-technicians and animal welfare inspectors was not known. For the categories with direct access to e-mail addresses; cattle hoof trimmers and some of the livestock hauliers, the response-rate was low and some e-mails also bounced, indicating the addresses were no longer in use. For hoof trimmers 27% of the addresses bounced and based on the addresses that did not bounce, the response rate was 17%. For the livestock hauliers that only received the questionnaire through e-mail, 21% of the addresses bounced and the response rate was 5%. However, for the paper questionnaires to livestock hauliers the response rate was 27%.

Descriptive statistics

Cattle farms were visited by most respondents (86%), while pig farms were visited by the least (43%). The number of farms visited varied, with hauliers and AI-technicians visiting most farms; 56% and 69% of them visited more than 20 farms per week (Table 1).

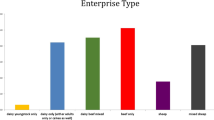

The reported on-farm biosecurity differed depending on species present on the farm (Table 2). In general, the highest proportion of biosecurity measures related to farm visits were reported to be in place on pig farms, followed by cattle farms. Farms with small ruminants or horses were reported to have less biosecurity measures in place. On these farms it was reported that there was seldom access to protective clothing or boots for the visitors, or even possibility for hand washing. Among veterinarians, a group in close contact with sick animals, 24% (n = 152) reported that hand washing facilities were available on none or almost none of the horse farms they visit. The corresponding figure for sheep farms was 31% (n = 100). There were also reported differences within the same farm types, i.e. different categories of visitors reported different proportions of certain biosecurity measures to be present on the farms they visit. This is illustrated through one example in Figure 1, showing availability of hand washing facilities on cattle farms. A clear majority of veterinarians and AI-technicians reported this to be available on all or almost all cattle farms they visit, which was in clear contrast to inspectors and livestock hauliers. A similar picture was also seen in pig farms. Among the veterinarians, 49% (n = 57) reported they could wash their hands on all pig farms they visit, but only 6% (n = 17) of the hauliers. In fact, 35% of the livestock hauliers reported they could wash their hands on none or almost none of the pig farms they visited. A clear difference was also seen for availability of protective clothing in cattle herds, where 81% (n = 21) of the hauliers reported protective clothing to be available on none or almost none of the cattle farms they visited, but only 21% (n = 57) of the AI-technicians reported it to be available on almost none of the farms (0% answered ‘none’). Corresponding patterns for protective clothing were seen on pig farms when comparing livestock hauliers and veterinarians; 41% of hauliers (n = 17) and 11% of veterinarians (n = 56) reported protective clothing to be available on none or almost none of the farms. Similar patterns were seen when comparing reported availability of boots for visitors both on cattle and pig-farms. On cattle farms 76% (n = 21) of the hauliers, 44% (n = 133) of the veterinarians and 37% (n = 59) of the AI-technicians reported that boots were available on none or almost none of the farms. For pig farms 63% (n = 57) of the veterinarians and 6% of the hauliers (n = 18) reported boots to be available on all or almost all farms.

When it came to biosecurity requirements made by farmers, there was also a perceived difference between the groups of visitors with 73% (n = 22) of hauliers reporting that none or almost none of cattle farmers they visit have any biosecurity requirements, whereas the other professionals reported a higher proportion of cattle farmers requiring biosecurity measures. Requirements also differed between animal species on the farms. Hauliers reported 38% (n = 16) of pig farmers to have biosecurity requirements. Of the veterinarians, 75% (n = 152) reported that none of the horse farms they visit have biosecurity requirements.

As for entering the farm buildings (a question that was specifically asked to livestock hauliers since they sometimes enter farms), there was a difference between pig farms compared to cattle, sheep and goat farms. Only 4% reported that they entered almost all pig farms (no-one wrote they entered all pig farms) whereas 43% wrote they entered all or almost all cattle farms and 39% that they entered all or almost all sheep and goat farms (n = 28).

For the factors affecting their own biosecurity routines, all categories of visitors had a high proportion of respondents reporting that ‘their own will not to spread disease’ (82-96%, total 95% n = 345) and ‘current disease outbreaks’ (91-95%, total 93% n = 341) were very important for their routines. Animal species present on the farm and herd size were regarded as very important by 28% (n = 336) and 15% (n = 343) of the respondents respectively. Again, there was a difference between groups. Only 4% (n = 28) of the livestock hauliers reported ‘farmers’ requests on biosecurity’ to be ‘irrelevant’ or ‘less important’ for their routines, whereas the corresponding figure for the inspectors was 35% (n = 77). Among both the AI-technicians (n = 57) and the hoof-trimmers (n = 11) 91% reported that the “market advantage of keeping a good hygiene” was ‘quite important’ or ‘very important’ for their routines, compared to 59% (n = 170) of the veterinarians.

There was also a difference between groups whether they had asked the farmer to improve the routines or not, with veterinarians being the group most often (56%, n = 186) reporting that they had asked farmers to improve the farm conditions for biosecurity for visitors ‘many times’. Only 11% (n = 28) of the livestock hauliers had asked this ’many times’. Among the inspectors, 60% (n = 82) had never asked farmers to improve the on-farm conditions for visitors’ biosecurity.

When assessing their own routines, 18% considered them to be ‘very good’, 58% ‘sufficient’, 8% ‘insufficient’ and 16% said this varied between farms (n = 343).

When looking at the perceived risk of spreading or contracting disease, there were also differences between the groups. In all groups, a majority (by group 54-87%; total 76%, n = 338) reported that there were infectious agents that they were afraid to spread between farms, with the highest number among veterinarians (87%, n = 146). For all the groups, there were higher proportions reporting they were afraid to spread disease, as compared to contracting disease themselves (21-63%, total 44%, n = 340). Among the respondents being afraid to spread or contract diseases, 205 gave examples of what they were afraid to spread (Table 3), and 128 gave examples of what they were afraid to contract (Table 4). The infections that the visitors were most afraid to spread between farms were; salmonellosis and ringworm followed by strangles and less well specified infections such as ‘diarrhoea’, ‘viral diseases’, and ‘respiratory diseases’. The same two infections, but in reversed order were in the two top positions for what the visitors were afraid to contract; ringworm first and in second place salmonellosis. These were followed by multiresistant bacteria and MRSA, EHEC, and listeriosis.

In total approximately half (52%, n = 338) of the respondents reported that there were obstacles to keeping a high level of biosecurity during farm visits. The number of respondents reporting obstacles was clearly highest among the veterinarians; 66% (n = 169) compared to 33-40% among the other groups. Of the respondents, 178 gave examples of obstacles and the majority of the examples (213) were related to conditions on the farm (Table 5). With the number one being ‘Lack of water, soap, wash basin, paper towels’, followed by ‘Inadequate equipment or lack of water to clean boots or equipment’ and in third place ‘Adequate protective clothing not available on the farm; non-existing, cold, dirty or wrong size’. There were also obstacles related to the working situation (22); ‘Lack of time, the working schedule does not allow adequate cleaning between farms’ or ‘Inadequate protective clothes, or not as many as needed provided by the employer’. Also for the suggestions on improvement (Table 6), measures related to conditions on the farm dominated (235) followed by measures related to communication (84). For the farm related suggestions, most related to ‘Protective clothing made available on-farm; clean, warm and of adequate size’ (65), followed by ‘Warm water, soap, wash basin and paper-towels available on-farm’ (57) and ‘Hard surface and water hose with adequate pressure available on the farm to clean boots and equipment, adequately located’ (34). Regarding communications there were suggestions on ‘Information to farmers, making farmers more aware, active dialogue with farmers, move the responsibility to the farmers’ (58) as well as ‘National biosecurity guidelines for both farmers and professionals’ (9).

In addition to the open ended questions, many of the respondents had written comments to the other questions (not included in the tables). Many of the comments gave additional information to the answers given and some comments clarified specific problems faced by certain groups of visitors. For example, the inspectors wrote that they always brought their own clean protective clothing, i.e. there was seldom need either for farmers to request more from them or, for them to ask the farmer for better conditions. Inspectors were also very concerned not to spread disease, expressing worries that it would give the inspectors as a group a bad reputation if they did. There were also comments related to how their task affected their work, and that they could experience threatening situations that sometimes affected the possibility to keep up good biosecurity. For cattle farms, there were many comments emphasising the difference between dairy herds and beef herds, where the biosecurity was perceived as better in the dairy herds. Related to pig herds there were comments that they in general were better compared to other species, but also that the routines were better while the eradication programme against Aujeszky’s disease was still ongoing. There were also comments stating that farmers in general, and even horse owners, almost always provided soap, warm water and towels twenty years ago, while this was less common nowadays. Regarding the horse stables, there were numerous comments about non-existing biosecurity, horse owners questioning the need for hand wash or protective clothing as well as comments related to horses being scared of the ordinary coats. Several veterinarians reported not using protective coats when treating horses for this reason. The status of the protective clothing provided by farmers generated many comments. In addition to recurrent comments about wet, cold and dirty clothes there were also comments about boots containing rat’s nests, mouse droppings or spider webs.

Discussion

Many of the respondents experienced obstacles for on-farm biosecurity, a remarkable number of the reported obstacles related to the very basics of biosecurity. Some respondents described a worsening situation. Sweden has historically had a strategy to control and eradicate diseases through specific programmes [29], and after eradication the routines are gradually relaxed, as was seen with Aujezsky’s disease (Sweden was declared officially free in 1996 [30]). Except for an outbreak of PRRS in 2007 and two vector borne diseases (Bluetongue and Schmallenberg), Sweden has not had any large outbreak of an exotic animal disease for decades [29–32], this may have had a negative impact on farmer awareness.

Responsibility and expectancy seem to be key issues mentioned by several respondents both in this study and in another current study focusing on the farmers’ perspectives (unpublished data). The visitors reported that the on-farm conditions did not allow an adequate level of biosecurity and that many farmers did not require any biosecurity routines, whereas farmers reported that they expect all visitors to be professional and take responsibility for not spreading any diseases. Recent national legislation in the area may help in clarifying the responsibilities [33] as well as the European Union proposal for a new Animal Health Law [7].

Several veterinarians reported that they had repeatedly asked farmers for improvements, but some concluded that veterinarians as a group have not been explicit enough. The benefits of veterinarians communicating messages about biosecurity to farmers, as well as farmers’ preference for receiving biosecurity information from their veterinarian has been identified in other studies [8, 18, 19, 34–36].

There were differences in the perceived conditions among different categories of visitors for the same category of farm. In part this can be explained by different types of farms visited, e.g. animal welfare inspectors visit another group of cattle farmers compared to AI-technicians. But there were also differences related to the task performed on the farm. For example, the animal welfare inspectors do not visit the farm at the farmer’s request, but more likely the opposite. They found it difficult to demand anything at all, and were afraid to be blamed for any disease introduction. Another example was the livestock hauliers who suggested that hand hygiene facilities be provided where they enter the farm, not only at the entrance for other visitors. These aspects should be kept in mind when developing biosecurity recommendations for different categories of professionals.

Limited access to water and soap was a general problem. This is surprising since the need for hand hygiene is old knowledge, described by Semmelweis in 1847 [37]. There are situations, e.g. on pasture, with no access to running water, but this can easily be solved, as was suggested, by bringing a water container, soap and a clean bucket. Several of the participants in the study also reported efforts to keep their hands clean despite poor conditions on the farm, e.g. stopping at a gas-station to wash their hands or using hand disinfectants and wipes in the car. Not all visitors may make this extra effort, and the effects of hand disinfectants without prior washing may not be sufficient [38]. In the extensive work to improve hand hygiene in human health, accessibility has been identified as an important factor for compliance with hand washing and disinfection routines [37].

Some responses indicated a lack of understanding among farmers of how infectious disease agents can spread through indirect contact. There were numerous comments on how protective clothing, when provided, was cold, damp and dirty. Clothes and boots in poor condition will not be used and will not fulfil the purpose of avoiding contamination of the visitor. There is a problem if farmers believe clothes and boots in such poor conditions to be adequate, but this may not only be related to lack of understanding. There are other influencing factors, like personality traits, which are discussed in a Canadian study where farmers were observed taking biosecurity risks through reusing shoe protections from the garbage [21].

The poor biosecurity conditions reported for farms with horses are alarming and there is obviously room for improvement. Need for improvement of biosecurity among horse owners and horse practitioners has also been identified in other countries [3, 39, 40]

Salmonella was the disease that most respondents were afraid to spread between farms. This may be related to the farm restrictions in the Swedish salmonella control programme [41]. The other diseases mentioned reflected the endemic disease situation in Sweden. However, some responses only included exotic animal diseases regulated by law. This may indicate an awareness of these diseases, but may also reflect an unawareness of the actual situation in Sweden. An increasing number of veterinarians in Sweden have a veterinary degree from abroad [42], from countries where these diseases may be endemic.

Several studies have concluded that people working with livestock are at higher risk of contracting zoonotic diseases and for colonisation with MRSA [28, 43]. In our study, 44% mentioned one or more zoonotic agents they were afraid to contract while working. From an Australian study it was reported that 35.3% of the veterinarians were concerned or very concerned for either themselves or for colleagues [27], but since the questions were asked in different ways these figures are not directly comparable. Ringworm was the disease that most persons mentioned as one of the diseases they were afraid to contract in their daily work, the same result was found in a study among veterinarians in the US [26]. Ringworm was also reported to be the most common zoonosis contracted by veterinarians both in Oregon and in South Africa [25, 44] and is probably a highly relevant zoonosis in Sweden as well since it is endemic in livestock. Salmonella came in second place, although the prevalence of salmonella in Swedish livestock is quite low [41]. This high ranking could be due to absence of other severe zoonotic infections such as brucellosis and tuberculosis [29, 30]. Multi-resistant bacteria and MRSA came in third place, although the prevalence is still believed to be low in Sweden [45]. There were also six persons stating that they were afraid to contract rabies, even though rabies was last confirmed in a Swedish animal in 1886 [30]. In recent years, however, there has been an increased illegal import of dogs to Sweden [46] and the fear of contracting rabies may be related to this.

This study used a convenience sample. Due to the distribution methods used, overall response rates cannot be assessed. How non-responders might differ from the responders, and the representativeness of the results, cannot be assessed either. It is possible that people with a particular interest in biosecurity, and perhaps frustrated by the lack of it, were more prone to answer the questionnaire, leading to a bias towards reporting poor biosecurity. Although persons with an interest in biosecurity may be overrepresented among the respondents, obstacles reported are likely to be generally present. However, the factors motivating biosecurity could be different among the non-respondents compared to the respondents. Despite these limitations, this study has captured views and opinions regarding on-farm biosecurity from groups of professionals where previously no information was available.

The many different (largely unknown) underlying factors affecting the types of farms visited and the uncertainty in the representativeness of both respondents and farms they visited was the reason for keeping to descriptive statistics, more advanced statistical methods would probably not be more informative.

There are a number of factors affecting biosecurity, both from the farmers’ and from the visitors’ perspectives. Lack of knowledge can be one reason for not implementing biosecurity routines [16]. However, human behaviour is complex and it is well known that not only knowledge is needed to change behaviour [47]. It is important also to understand the experienced obstacles and motivators for biosecurity. This study is part of a project in which farmers are also asked about hindrances and motivators for biosecurity. Trying to approach the on-farm biosecurity related to professionals visiting farms from two different perspectives will add to the understanding of this issue.

Conclusions

Many of the respondents reported obstacles for keeping adequate biosecurity related to on-farm conditions, and a large proportion of farms visited were reported to lack the very basics for visitors’ biosecurity. Different visitors seemed to have different conditions for maintaining biosecurity on farms. There was a gap when it came to responsibility and this need to be clarified; visitors need to take responsibility for avoiding spread of disease, while farmers need to assume responsibility for providing adequate conditions for on-farm biosecurity.

References

van Schaik G, Schukken YH, Nielen M, Dijkhuizen AA, Barkema HW, Benedictus G: Probability of and risk factors for introduction of infectious diseases into Dutch SPF dairy farms: a cohort study. Prev Vet Med. 2002, 54: 279-289. 10.1016/S0167-5877(02)00004-1.

van Schaik G, Schukken YH, Nielen M, Dijkhuizen AA, Benedictus G: Risk factors for introduction of BHV1 into BHV1-free Dutch dairy farms: a case–control study. Vet Q. 2001, 23: 71-76. 10.1080/01652176.2001.9695085.

Firestone SM, Lewis FI, Schemann K, Ward MP, Toribio JA, Dhand NK: Understanding the associations between on-farm biosecurity practice and equine influenza infection during the 2007 outbreak in Australia. Prev Vet Med. 2013, 11: 028-36.

Ellis-Iversen J, Smith RP, Gibbens JC, Sharpe CE, Dominguez M, Cook AJ: Risk factors for transmission of foot-and-mouth disease during an outbreak in southern England in 2007. Vet Rec. 2011, 168: 128-10.1136/vr.c6364.

Ribbens S, Dewulf J, Koenen F, Maes D, de Kruif A: Evidence of indirect transmission of classical swine fever virus through contacts with people. Vet Rec. 2007, 160: 687-690. 10.1136/vr.160.20.687.

Ohlson A, Heuer C, Lockhart C, Tråven M, Emanuelson U, Alenius S: Risk factors for seropositivity to bovine coronavirus and bovine respiratory syncytial virus in dairy herds. Vet Rec. 2010, 167: 201-206. 10.1136/vr.c4119.

Proposal for a regulation of the european parliament and of the council on animal health swd(2013) 160 final.http://ec.europa.eu/food/animal/docs/ah-law-proposal_en.pdf,

Gunn GJ, Heffernan C, Hall M, McLeod A, Hovi M: Measuring and comparing constraints to improved biosecurity amongst GB farmers, veterinarians and the auxiliary industries. Prev Vet Med. 2008, 84: 310-323. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2007.12.003.

Ribbens S, Dewulf J, Koenen F, Mintiens K, De Sadeleer L, de Kruif A, Maes D: A survey on biosecurity and management practices in Belgian pig herds. Prev Vet Med. 2008, 83: 228-241. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2007.07.009.

Valeeva NI, van Asseldonk MA, Backus GB: Perceived risk and strategy efficacy as motivators of risk management strategy adoption to prevent animal diseases in pig farming. Prev Vet Med. 2011, 102: 284-295. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2011.08.005.

Heffernan C, Nielsen L, Thomson K, Gunn G: An exploration of the drivers to bio-security collective action among a sample of UK cattle and sheep farmers. Prev Vet Med. 2008, 87: 358-372. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2008.05.007.

Costard S, Porphyre V, Messad S, Rakotondrahanta S, Vidon H, Roger F, Pfeiffer DU: Multivariate analysis of management and biosecurity practices in smallholder pig farms in Madagascar. Prev Vet Med. 2009, 92: 199-209. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2009.08.010.

Siekkinen KM, Heikkilä J, Tammiranta N, Rosengren H: Measuring the costs of biosecurity on poultry farms: a case study in broiler production in Finland. Acta Vet Scand. 2012, 54: 12-10.1186/1751-0147-54-12.

Zhang YH, Li CS, Liu CC, Chen KZ: Prevention of losses for hog farmers in China: insurance, on-farm biosecurity practices, and vaccination. Res Vet Sci. 2013, 95: 819-24. 10.1016/j.rvsc.2013.06.002.

Kristensen E, Jakobsen EB: Danish dairy farmers’ perception of biosecurity. Prev Vet Med. 2011, 99: 122-129. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2011.01.010.

Sayers RG, Sayers GP, Mee JF, Good M, Bermingham ML, Grant J, Dillon PG: Implementing biosecurity measures on dairy farms in Ireland. Vet J. 2013, 197: 259-267. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2012.11.017.

Brennan ML, Christley RM: Biosecurity on cattle farms: a study in north-west England. PLoS One. 2012, 7: e28139-10.1371/journal.pone.0028139.

Simon-Grifé M, Martín-Valls GE, Vilar-Ares MJ, García-Bocanegra I, Martín M, Mateu E, Casal J: Biosecurity practices in Spanish pig herds: perceptions of farmers and veterinarians of the most important biosecurity measures. Prev Vet Med. 2013, 110: 223-231. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2012.11.028.

Hernández-Jover M, Taylor M, Holyoake P, Dhand N: Pig producers’ perceptions of the Influenza Pandemic H1N1/09 outbreak and its effect on their biosecurity practices in Australia. Prev Vet Med. 2012, 106: 284-294. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2012.03.008.

Laanen M, Persoons D, Ribbens S, de Jong E, Callens B, Strubbe M, Maes D, Dewulf J: Relationship between biosecurity and production/antimicrobial treatment characteristics in pig herds. Vet J. 2013, 198: 508-512. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.08.029.

Racicot M, Venne D, Durivage A, Vaillancourt JP: Evaluation of the relationship between personality traits, experience, education and biosecurity compliance on poultry farms in Quebec, Canada. Prev Vet Med. 2012, 103: 201-207. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2011.08.011.

Racicot M, Venne D, Durivage A, Vaillancourt JP: Evaluation of strategies to enhance biosecurity compliance on poultry farms in Quebec: effect of audits and cameras. Prev Vet Med. 2012, 103: 208-218. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2011.08.004.

Racicot M, Venne D, Durivage A, Vaillancourt JP: Description of 44 biosecurity errors while entering and exiting poultry barns based on video surveillance in Quebec, Canada. Prev Vet Med. 2011, 100: 193-199. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2011.04.011.

Nöremark M, Frössling J, Lewerin SS: Application of routines that contribute to on-farm biosecurity as reported by Swedish livestock farmers. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2010, 57: 225-236.

Gummow B: A survey of zoonotic diseases contracted by South African veterinarians. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 2003, 74: 72-76.

Wright JG, Jung S, Holman RC, Marano NN, McQuiston JH: Infection control practices and zoonotic disease risks among veterinarians in the United States. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2008, 232: 1863-1872. 10.2460/javma.232.12.1863.

Dowd K, Taylor M, Toribio JA, Hooker C, Dhand NK: Zoonotic disease risk perceptions and infection control practices of Australian veterinarians: call for change in work culture. Prev Vet Med. 2013, 111: 17-24. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2013.04.002.

Baker WS, Gray GC: A review of published reports regarding zoonotic pathogen infection in veterinarians. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2009, 234: 1271-1278. 10.2460/javma.234.10.1271.

SVA (National Veterinary Institute): Sjukdomsrapportering 2011, En uppdatering av regeringsrapporten 2006. SVA:s rapportserie 23 ISSN 1654–7098. 2012

SVA (National Veterinary Institute): Surveillance of infectious diseases in animals and humans in Sweden 2012. SVA:s rapportserie 26 ISSN 1654–7098. 2013

Carlsson U, Wallgren P, Renström LH, Lindberg A, Eriksson H, Thoren P, Eliasson-Selling L, Lundeheim N, Nörregård E, Thörn C, Elvander M: Emergence of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome in Sweden: detection, response and eradication. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2009, 56: 121-131. 10.1111/j.1865-1682.2008.01065.x.

Sternberg Lewerin S, Hallgren G, Mieziewska K, Berndtsson LT, Chirico J, Elvander M: Infection with bluetongue virus serotype 8 in Sweden in 2008. Vet Rec. 2010, 167: 165-170. 10.1136/vr.c3380.

Jordbruksverket (Swedish Board of Agriculture): Statens jordbruksverks föreskrifter och allmänna råd om förebyggande och särskilda åtgärder avseende hygien m.m. för att förhindra spridning av zoonoser och andra smittämnen. I. SJVFS 2013:14, K112. 2013, Jordbruksverket (Swedish Board of Agriculture)

Schemann K, Firestone SM, Taylor MR, Toribio JA, Ward MP, Dhand NK: Horse owners’/managers’ perceptions about effectiveness of biosecurity measures based on their experiences during the 2007 equine influenza outbreak in Australia. Prev Vet Med. 2012, 106: 97-107. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2012.01.013.

Garforth CJ, Bailey AP, Tranter RB: Farmers’ attitudes to disease risk management in England: a comparative analysis of sheep and pig farmers. Prev Vet Med. 2013, 110: 456-466. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2013.02.018.

Brennan ML, Christley RM: Cattle producers’ perceptions of biosecurity. BMC Vet Res. 2013, 9: 71-10.1186/1746-6148-9-71.

Hugonnet S, Pittet D: Hand hygiene-beliefs or science?. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2000, 6: 350-356.

Racicot M, Kocher A, Beauchamp G, Letellier A, Vaillancourt JP: Assessing most practical and effective protocols to sanitize hands of poultry catching crew members. Prev Vet Med. 2013, 111: 92-99. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2013.03.014.

Aceto H, Bender JB, Clark C, Daniels JB, Davis MA, Hinchcliff KW, Johnson JR, McClure J, Perkins GA, Pusterla N, Traub-Dargatz JL, Weese JS, Whittem TL: Report of the third Havemeyer workshop on infection control in equine populations. Equine Vet J. 2013, 45: 131-136. 10.1111/evj.12000.

Rosanowski SM, Rogers CW, Cogger N, Benschop J, Stevenson MA: The implementation of biosecurity practices and visitor protocols on non-commercial horse properties in New Zealand. Prev Vet Med. 2012, 107: 85-94. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2012.05.001.

Lewerin SS, Skog L, Frössling J, Wahlström H: Geographical distribution of salmonella infected pig, cattle and sheep herds in Sweden 1993–2010. Acta Vet Scand. 2011, 53: 51-10.1186/1751-0147-53-51.

Jonsson P: Ledare: policydokument allt viktigare för veterinärkåren. Svensk Veterinärtidning. 2013, 2: 3-

Garcia-Graells C, Antoine J, Larsen J, Catry B, Skov R, Denis O: Livestock veterinarians at high risk of acquiring methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398. Epidemiol Infect. 2012, 140: 383-389. 10.1017/S0950268811002263.

Jackson J, Villarroel A: A survey of the risk of zoonoses for veterinarians. Zoonoses Public Health. 2012, 59: 193-201. 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2011.01432.x.

Unnerstad HE, Bengtsson B, Horn Af Rantzien M, Börjesson S: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus containing mecC in Swedish dairy cows. Acta Vet Scand. 2013, 55: 6-10.1186/1751-0147-55-6.

Pressrelease, smuggling av hundvalpar stoppades,.http://www.jordbruksverket.se/formedier/nyheter/nyheter2012/smugglingavhundvalparstoppades.5.5ce6c400139a12671c880001762.html,

Kollmuss A, Agyeman J: Mind the gap: why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior?. Environ Educ Res. 2002, 8: 239-260. 10.1080/13504620220145401.

Acknowledgements

The project was funded by the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency (MSB). We acknowledge all participants in the study and Svenska Veterinärförbundet, Veterinärer i Sverige, Växa, Skåne semin, Rådgivarna i Sjuhärad and Länsstyrelsernas djurskyddschefer that were willing to support the study by distributing the questionnaires within their organizations and we also acknowledge Jenny Frössling for valuable advice throughout the study. The Swedish Board of Agriculture is acknowledged for providing the data on registered livestock hauliers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

There were no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MN and SS designed the study. MN developed the questionnaire, collected data, analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. SSL participated in the analyses of data and revised the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

13028_2013_945_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Additional file 1: Questionnaire, translated to English. Questionnaire regarding biosecurity to persons visiting farms in their profession, translated to English. (PDF 134 KB)

13028_2013_945_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Additional file 2: Questionnaire, Swedish. Questionnaire regarding biosecurity to persons visiting farms in their profession, Swedish original version. (PDF 122 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Nöremark, M., Sternberg-Lewerin, S. On-farm biosecurity as perceived by professionals visiting Swedish farms. Acta Vet Scand 56, 28 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1751-0147-56-28

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1751-0147-56-28