Abstract

Background

The goal of this study was to estimate the distribution of udder pathogens and their antibiotic resistance in Estonia during the years 2007-2009.

Methods

The bacteriological findings reported in this study originate from quarter milk samples collected from cows on Estonian dairy farms that had clinical or subclinical mastitis. The samples were submitted by local veterinarians to the Estonian Veterinary and Food Laboratory during 2007-2009. Milk samples were examined by conventional bacteriology. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed with the disc diffusion test. Logistic regression with a random herd effect to control for clustering was used for statistical analysis.

Results

During the study period, 3058 clinical mastitis samples from 190 farms and 5146 subclinical mastitis samples from 274 farms were investigated. Positive results were found in 57% of the samples (4680 out of 8204), and the proportion did not differ according to year (p > 0.05). The proportion of bacteriologically negative samples was 22.3% and that of mixed growth was 20.6%. Streptococcus uberis (Str. uberis) was the bacterium isolated most frequently (18.4%) from cases of clinical mastitis, followed by Escherichia coli (E. coli) (15.9%) and Streptococcus agalactiae (Str. agalactiae) (11.9%). The bacteria that caused subclinical mastitis were mainly Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) (20%) and coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS) (15.4%). The probability of isolating S. aureus from milk samples was significantly higher on farms that had fewer than 30 cows, when compared with farms that had more than 100 cows (p < 0.005). A significantly higher risk of Str. agalactiae infection was found on farms with more than 600 cows (p = 0.034) compared with smaller farms. The proportion of S. aureus and CNS isolates that were resistant to penicillin was 61.4% and 38.5%, respectively. Among the E. coli isolates, ampicillin, streptomycin and tetracycline resistance were observed in 24.3%, 15.6% and 13.5%, respectively.

Conclusions

This study showed that the main pathogens associated with clinical mastitis were Str. uberis and E. coli. Subclinical mastitis was caused mainly by S. aureus and CNS. The number of S. aureus and Str. agalactiae isolates depended on herd size. Antimicrobial resistance was highly prevalent, especially penicillin resistance in S. aureus and CNS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bovine mastitis is the most common disease in dairy cows worldwide, and antimicrobial therapy is the primary tool for the treatment of mastitis. The prevalence of mastitis pathogens and their antimicrobial resistance have been investigated in numerous studies around the world. The main pathogens that cause subclinical mastitis are coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS), Corynebacterium bovis (C. bovis) and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) [1–5]. Coliforms, Streptococcus uberis (Str. uberis) and S. aureus are the pathogens isolated most frequently from clinical mastitis samples [6–8]. Streptococcus agalactiae (Str. agalactiae) has been largely eradicated from herds in Europe [3], but in studies from the United States, 7.7% and 13.1% of samples contained Str. agalactiae[9, 10].

Several methods, such as disc diffusion, agar dilution, broth dilution and broth microdilution are suitable for in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Depending on the study design and the methodology used, the antimicrobial susceptibility of udder pathogens varies greatly between studies. For example, studies from France and the UK have reported a high prevalence of penicillin-resistant S. aureus (36.2%, 56%) [11, 12], whereas a low percentage of resistant isolates (4-9%) were found in the Netherlands and Norway [13, 14]. The streptococci that cause mastitis are susceptible to β-lactam antibiotics; however, resistance to macrolides and lincosamides is notable [13, 15]. In vitro resistance of E. coli to different antimicrobials has been reported to be low [13, 14, 16, 17].

National studies of mastitis prevalence provide important information through the monitoring of national udder health status, and they enable national guidelines to be developed for the prudent use of antibiotics in each country [18]. During recent decades, only broad-spectrum antibiotics have been used for the treatment of clinical mastitis in Estonia. For example, in the years 2006-2009, 15 different combinations of antibiotics were available for use in 18 intramammary preparations that were authorised by the Estonian State Medical Agency [19]. Given that a large overview of udder pathogens and their antibiotic resistance has not been performed in Estonia, the goal of this study was to estimate the distribution of udder pathogens and their antibiotic resistance during the years 2007-2009 in Estonia.

Methods

Sample collection

Milk samples were submitted to the Estonian Veterinary and Food Laboratory during the period 2007-2009. Quarter milk samples were collected from cows on Estonian dairy farms by local veterinarians or farmers. Clinical mastitis was diagnosed when visible abnormalities of udder (swelling) were detected or milk from a quarter had abnormal viscosity (watery, thicker than normal), colour (yellow, blood-tinged) or consistency (flakes or clots) [20]. Normal milk appearance, together with a positive California Mastitis Test result (score greater than 1), was used to make a diagnosis of subclinical mastitis.

The samples were sent to the laboratory either for isolation of the clinical mastitis pathogen and determination of its antimicrobial susceptibility or to determine the reason for an increased somatic cell count.

Laboratory analysis

Bacterial species were identified using accredited methodology based on the National Mastitis Council [21] standards. From each sample, 0.01 ml of milk was cultured on blood-esculin agar and incubated for 48 h at 37°C. The plates were examined after 24 and 48 h of incubation. A minimum of five colonies of the same type of bacterium was recorded as bacteriologically positive, and growth of more than two types of bacterial colonies was categorised as mixed growth. No bacterial growth was recorded when fewer than five colony-forming units were detected during 48 h of incubation.

Once they had been isolated and identified, pure cultures of udder pathogens were tested for antibacterial susceptibility with the disc diffusion assay on Mueller-Hinton agar. Testing was performed according to the recommendation of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) document M31-A2 in the years 2007-2008 and M31-A3 in 2009 [22, 23]. Quality control strains, S. aureus ATCC® 25923, E. coli ATCC® 25922, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC® 27853 and Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC® 49619, were included with each batch of isolates tested. The antimicrobial susceptibility of Gram-positive bacteria was tested with penicillin, ampicillin, cephalothin, clindamycin, erythromycin, gentamycin, trimethoprim/sulfa and tetracycline. The antimicrobial susceptibility of Gram-negative bacteria was tested with ampicillin, gentamycin, trimethoprim/sulfa, tetracycline, enrofloxacin, streptomycin, neomycin and cefaperazone. The list of antibiotics in susceptibility testing may vary, different veteriarians preferred different set of antibiotics in order to find accurate treatment after getting the laboratory test results.

The criteria for the interpretation of zone diameter used in this study are described in Table 1.

Data analysis

The farm, herd size and year were recorded and categorised before statistical analysis. A logistic regression model with a random herd effect for the control of clustering was used for all of the analyses in this study. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.005.

The influence of milk samples with mixed growth or no bacterial growth on the occurrence of clinical or subclinical mastitis was assessed. Potential interactions (no growth or mixed growth × year) were assessed in the logistic regression model. The effects of herd size and year on the pathogens that caused clinical and subclinical mastitis were analysed. These analyses were conducted using Stata 10.2 [24].

Results

Isolation of mastitis pathogens

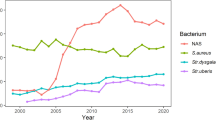

During the study period, 3058 clinical mastitis samples from 190 farms and 5146 subclinical mastitis samples from 274 farms were investigated (Table 2).

Positive results were found in 57% of the samples (4680 out of 8204), and this proportion did not differ according to year (p > 0.05). The proportion of bacteriologically negative samples was 22.3% and that of mixed growth 20.6%. There was a significantly higher chance (OR = 1.15, 95% CI = 1.01, 1.33, p = 0.042) of finding bacteriologically negative samples in presence of subclinical mastitis (n = 1317, 25.6%) in comparison with clinical mastitis (n = 554, 16.8%). The probability of obtaining mixed growth from milk samples was also significantly higher (OR = 2.2, 95% CI = 1.9, 2.6, p < 0.001) if subclinical mastitis was found. The distribution of bacterial species isolated from samples from cows with clinical and subclinical mastitis is shown in Table 3. Among the bacteriologically positive (n = 2016) clinical mastitis samples, Str. uberis was the bacterium isolated most frequently (n = 371; 18.4% of the positive samples), followed by E. coli (n = 321; 15.9%) and Str. agalactiae (n = 293; 11.9%). S. aureus (n = 532; 20%) and CNS (n = 411; 15.4%) were the bacteria isolated most commonly from milk in cases of subclinical mastitis, followed by Corynebacterium spp. (n = 395; 14.8%).

The probability of isolating S. aureus from milk samples was significantly higher on farms that had fewer than 30 cows, when compared with farms with more than 100 cows (OR = 0.2, 95% CI = 0.11, 0.53, p < 0.005). Also, there was a significantly higher risk of diagnosing Str. agalactiae on farms with more than 600 cows (OR = 17.6, 95% CI = 1.2, 259.1, p = 0.034) compared with smaller farms.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

The percentage of S. aureus isolates resistant to penicillin and ampicillin was 61.4% and 59.5%, respectively. In addition, CNS showed resistance to penicillin and ampicillin (38.5% and 34.4%), but resistance to erythromycin and lincomycin was also common (14.9% and 17.6%). Six isolates (3.8%) of S. aureus and three isolates (3.6%) of CNS were resistant to cephalothin (Table 4).

All streptococci (Table 5) were susceptible to penicillin, ampicillin and cephalothin, except for one isolate of Str. uberis. Of the 90 isolates of Str. dysgalactiae, 19.8% were classified with intermediate susceptibility and 32.2% with resistance to tetracycline. Of a total of 151 isolates of Str. uberis, 7.3% with intermediate susceptibility and 14.3% with resistance to tetracycline were recorded. Among the E. coli isolates (Table 6), the highest percentage of isolates showing intermediate susceptibility and resistance were observed with ampicillin, neomycin, streptomycin and tetracycline. E. coli. was 98.4% susceptible to enrofloxacin and 100% to cefaperazone.

Discussion

The results of the present study were based on an analysis of milk samples submitted to an Estonian National Veterinary Laboratory over a three-year period. The laboratory protocols did not change during the study period. Of the samples investigated, 22.3% were bacteriologically negative. Several other studies have also demonstrated bacteriologically negative findings in 17.7-26.5% cases of clinical mastitis [12, 25] and as many as 28.7-38.6% of subclinical mastitis [12, 26], which is in line with our results. The possible reasons for bacteriologically negative findings in milk samples could be the presence of antibacterial substances in the milk that lead to a decrease in the viability of bacteria in the culture [27], or failures in conventional culture compared with identification of bacteria using the real-time polymerase chain reaction [28].

In the present study, E. coli and Str. uberis were the pathogens isolated most frequently from clinical mastitis, while S. aureus, CNS and Corynebacterium spp. caused mainly subclinical mastitis. The same results were shown in an Estonian study ten years ago, where C. bovis (47.5%), S. aureus (21%) and CNS (15.8%) were the pathogens isolated most commonly from cases of subclinical mastitis [29]. The isolation rate of Str. agalactiae was surprisingly high in our study.

We found a strong association between the isolation of Str. agalactiae and very large-scale farms. In total, there are 98000 dairy cows in Estonia and the mean herd size is 88 cows [30]. Rapid changes in management style (from tie-stalls to free-stalls) have occurred during the last eight years, which may explain the coexistence of environmental pathogens together with Str. agalactiae. Although teat disinfection and dry cow therapy is a common routine on Estonian dairy farms, proper eradication programmes for Str. agalactiae have not been employed. In contrast, an increased probability of finding S. aureus was correlated with farms with fewer than 30 cows. The average age of cows on small farms was 5.3 years, compared with 4.3 years on farms on which more than 300 cows were kept [30]. The culling policy may be different, and the owners of smaller farms may keep (possibly chronically infected) cows in the herd for a longer period of time.

The disc diffusion method for in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility testing was used in this study. This technique is the most widely used method for determination of the susceptibility of animal pathogens, especially in clinical work when it is necessary to determine the correct treatment. The primary disadvantage of using this method when monitoring development of resistance is that outcomes are reported on a qualitative basis (sensitive, intermediate, or resistant), and subtle changes in susceptibility may not be apparent. Therefore any comparison with studies that use other methods of susceptibility testing is not acceptable [31].

Generally in our study, the in vitro antimicrobial resistance of the isolates examined from samples of clinical mastitis were high. Isolates of S. aureus had an alarming level of resistance to penicillin (61.4%) and ampicillin (59.5%), whereas CNS exhibited a lower degree of resistance to penicillin and ampicillin (38.5%; 34.4%). The reported percentages for penicillin resistant S. aureus in cases of clinical mastitis, detected by the disc diffusion method, are 50.4% and 35.4% in the USA [10, 32], 63.3% in Turkey [33] and 12% in Northern Germany [34]. In addition, cephalothin resistance among staphylococci was found in our study. Although reports of methicillin-resistant staphylococci causing bovine mastitis are rare, those samples found in our study need further investigation in order to prove or exclude the presence of the mecA gene. In the present study, both staphylococci and streptococci showed resistance to erythromycin and lincomycin, but the figures for resistance in annual reports from some other countries show a low prevalence of lincomycin and erythromycin resistance in S. aureus and CNS [13, 14, 35]. Given that S. aureus and CNS were the pathogens isolated most frequently from cases of subclinical mastitis, one possible explanation for resistance to several antibiotics may be the collection and submission to the laboratory of milk samples from chronic clinical mastitis (which demonstrate poor treatment efficacy). Therefore, random sampling strategies should be used to provide a good evaluation of antimicrobial susceptibility.

The level of resistance of E. coli and Klebsiella spp. was high against all tested antimicrobials, except cefaperazone and enrofloxacin. Coliforms are often resistant to more than one antimicrobial [36, 37], and the number of multiresistant strains may influence the resistance figures. Coliform bacteria isolated from cases of mastitis may reflect the general situation of resistance in the herd and can be considered more as an indicator of the bacteria present than an indicator of specific pathogens from the udder [36]. All of the bacterial species investigated in the present study showed resistance to tetracycline. A possible explanation for this phenomenon could be that tetracycline has been the class of antimicrobial most widely used for treatment of several infections for many years. In addition, tetracycline has been found in multiresistant patterns with penicillin and streptomycin [33, 37].

Statistical data from the Estonian State Medical Agency confirmed [19] that alltogether 209880 single intramammary syringes for lactating cows and 205648 for dry cow therapy were sold in the year 2009. Ampicillin and cloxacillin combinations, cephalosporins with aminoglycosides, and lincomycin with neomycin were the most common choices for the treatment of mastitis in lactating cows. For example, 255 grams of intramammary lincomycin (pure antimicrobial) and 44.2 grams of intramammary cephalosporins per thousand dairy cows were sold for the treatment of clinical mastitis in 2009 [19]. However, only 73.4 grams of penicillin G was used per thousand dairy cows for intramammary treatment of clinical mastitis. The use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and antibiotic combinations may influence the resistance of mastitis pathogens. In addition, bacteriological examination of milk samples before treatment of clinical mastitis is not a common practice in Estonia. According to the available data in Sweden, intramammary and intramuscular penicillin G [38] are used in over 80% of cases for treatment of clinical mastitis, but the prevalence of resistance of S. aureus to penicillins is only 7.1% [36]. In Finland, penicillin G and some broad-spectrum β-lactam antibiotics are used in the treatment of clinical mastitis, but the prevalence of resistance in S. aureus is only 13% [39]. Bacteriological examination before treatment is common in both countries.

Considering these results, we can assume that the main reason for the occurrence of a high number of resistant strains in Estonian herds is the wide use of broad-spectrum antimicrobials and the long-term presence of infected cows in herds.

Conclusion

This study showed that the main pathogens that caused clinical mastitis were Str. uberis and E. coli. Subclinical mastitis was caused mainly by S. aureus and CNS. A relatively high number of isolates of Str. agalactiae were cultured from both types of case. The number of S. aureus and Str. agalactiae isolates depended on herd size. Among the bacteria investigated, the prevalence of antimicrobial resistance was extremely high, especially penicillin resistance in S. aureus and CNS.

References

Pitkälä A, Haveri M, Pyörälä S, Myllys V, Honkanen-Buzalski T: Bovine mastitis in Finland 2001--prevalence, distribution of bacteria, and antimicrobial resistance. J Dairy Sci. 2004, 87: 2433-2441.

Osterås O, Sølverød L, Reksen O: Milk culture results in a large Norwegian survey-effects of season, parity, days in milk, resistance, and clustering. J Dairy Sci. 2006, 89: 1010-102.

Piepers S, De Meulemeester L, de Kruif A, Opsomer G, Barkema HW, De Vliegher S: Prevalence and distribution of mastitis pathogens in subclinically infected dairy cows in Flanders, Belgium. J Dairy Res. 2007, 74: 478-483. 10.1017/S0022029907002841.

Tenhagen BA, Köster G, Wallmann J, Heuwieser W: Prevalence of mastitis pathogens and their resistance against antimicrobial agents in dairy cows in Brandenburg, Germany. J Dairy Sci. 2006, 89: 2542-2551. 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72330-X.

Botrel MA, Haenni M, Morignat E, Sulpice P, Madec JY, Calavas D: Distribution and antimicrobial resistance of clinical and subclinical mastitis pathogens in dairy cows in Rhône-Alpes, France. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2009, 17-

Sųlverod L, Branscum AJ, Østerås O: Relationships between milk culture results and treatment for clinical mastitis or culling in Norwegian dairy cattle. J Dairy Sci. 2006, 89: 2928-2937.

Aarestrup FM, Jensen NE: Development of penicillin resistance among Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine mastitis in Denmark and other countries. Microb Drug Resist. 1998, 4: 247-256. 10.1089/mdr.1998.4.247.

Riekerink O, Barkema HW, Kelton DF, Scholl DT: Incidence rate of clinical mastitis on Canadian dairy farms. J Dairy Sci. 2008, 91: 1366-1377. 10.3168/jds.2007-0757.

Wilson DJ, Gonzales RN, Das HH: Bovine mastitis pathogens in New York and Pennsylvania: Prevalence and effects on somatic cell count and milk production. J Dairy Sci. 1997, 80: 2592-2598. 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(97)76215-5.

Makovec JA, Ruegg PL: Antimicrobial resistance of bacteria isolated from dairy cow milk samples submitted for bacterial culture: 8,905 samples (1994-2001). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2003, 222: 1582-1589. 10.2460/javma.2003.222.1582.

Guerin-Fauble V, Carret G, Houffschmitt P: In vitro activity of 10 antimicrobial agents against bacteria isolated from cows with clinical mastitis. Vet Rec. 2003, 152: 466-471. 10.1136/vr.152.15.466.

Bradley AJ, Leach KA, Breen JE, Green LE, Green MJ: Survey of the incidence and aetiology of mastitis on dairy farms in England and Wales. Vet Rec. 2007, 160: 253-257. 10.1136/vr.160.8.253.

MARAN: Monitoring of antimicrobial resistance and antibiotic usage in animals in the Netherlands in 2008. 2008, [http://www.cvi.wur.nl]

NORM/NORM-VET 2003: Usage of Antimicrobial Agents and Occurrence of AntimicrobialResistance in Norway. Tromsø/Oslo. 2004

Guerin-Faublee V, Tardy F, Bouveron C, Carret C: Antimicrobial susceptibility of Streptococcus species isolated from clinical mastitis in dairy cows. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2002, 19: 219-226. 10.1016/S0924-8579(01)00485-X.

FINRES-Vet 2005-2006: Finnish veterinary antimicrobial resistance monitoring and consumption of antimicrobial agents. Evira publications. 2007, [http://www.evira.fi/uploads/WebShopFiles/1198141211941.pdf]

SVARM, 2004: Swedish veterinary antimicrobial resistance monitoring. The National Veterinary Institute(SVA), Uppsala, Sweden. ISSN 1650-6332

Sampimon O, Barkema HW, Berends I, Sol J, Lam T: Prevalence of intramammary infection in Dutch dairy herds. J Dairy Res. 2009, 76: 129-136. 10.1017/S0022029908003762.

Estonia State Medical Agency:Official annual report. Usage of antimicrobial agents in animals. Estonia. 2009,

IDF: Suggested interpretation of mastitis terminology. Int Dairy Fed Bull. 1999, 3-26. 338

Hogan JS, Gonzales RN, Harmon RJ, Nickerson SC, Oliver SP, Smith KL: Laboratory Handbook on Bovine Mastitis. 1999, National Mastitis Council Inc, Madison, WI, Revised

Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI): Performance standards for antimicrobial disk and dilution susceptibility tests for bacteria isolated from animals: Approved standard. NCCLS document M31-A2. 2002, Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute, Wayne, PA, USA, Second

Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI): Performance standards for antimicrobial disk and dilution susceptibility tests for bacteria isolated from animals: Approved standard. CLSI document M31-A3. 2008, Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute, Wayne, PA, USA, Third

Stata 10.2. 2008, Stata® Statacorp LP, College Station, USA

Sargeant JM, Morgan SH, Leslie KE, Ireland MJ, Anna Bashiri A: Clinical mastitis in dairy cattle in Ontario: Frequency of occurrence and bacteriological isolates. Can Vet J. 1998, 39: 33-39.

Roesch M, Doherr MG, Schären W, Schällibaum M, Blum JV: Subclinical mastitis in dairy cows in Swiss organic and conventional production systems. J Dairy Res. 2007, 74: 86-92. 10.1017/S002202990600210X.

Rainard P, Riollet C: Innate immunity of bovine mammary gland. Vet Res. 2006, 37: 369-400. 10.1051/vetres:2006007.

Taponen S, Salmikivi L, Simojoki H, Koskinen MT, Pyörälä S: Real-time polymerase chain reaction-based identification of bacteria in milk samples from bovine clinical mastitis with no growth in conventional culturing in milk. J Dairy Sci. 2009, 92: 2610-2617. 10.3168/jds.2008-1729.

Haltia L, Honkanen-Buzalski T, Spiridonova I, Olkonen A, Myllys V: A study of bovine mastitis, milking procedures and management practises on 25 Estonian dairy herds. Acta Vet Scan. 2006, 48: 22-10.1186/1751-0147-48-22.

Animal Recording Centre: Annual Report Estonia. 2009

Schwarz S, Silley P, Shabbir S, Woodword N, van Duijkeren E, Johnson AP, Gaastra W: Editorial. Assessing the antimicrobial susceptibilty of bacteria obtained from animals. Vet Microbiol. 2009, 141: 1-4. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.12.013.

Erskine RJ, Walker RD, Bolin CA, Bartlett PC, White DG: Trends in antibacterial susceptibility of mastitis pathogens during a seven-year period. J Dairy Sci. 85: 1111-1118. 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(02)74172-6.

Güler L, Ok Ü, Gündüz K, Gülcü Y, Hadimli HH: Antimicrobial susceptibility and coagulase gene typing of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine clinical mastitis cases in Turkey. Dairy Sci. 2005, 88: 3149-3154.

Schröder A, Hoedemaker M, Klein G: Resistance of mastitis pathogens in Northern Germany. Berl Münch Tierärztl Wochenschr. 2005, 9/10: 393-398.

SVARM: Swedish veterinary antimicrobial resistance monitoring. 2002, The National Veterinary Institute(SVA), Uppsala, Sweden, ISSN 1650-6332

Bengsston B, Unnerstad HE, Ekman T, Artursson K, Nilsson-Öst M, Persson Waller K: Antimicrobial suspectibility of udder pathogens from cases of acute clinical mastitis in dairy cows. Vet Microbiol. 2009, 36: 142-149.

Lehtolainen T, Schwimmer A, Shpigel NY, Honkanen-Buzalski T, Pyörälä S: In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of Escherichia coli isolates from clinical bovine mastitis in Finland and Israel. J Dairy Sci. 2002, 86: 3927-3932. 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(03)74001-6.

Landin H: Treatment of mastitis in Swedish dairy production. Svensk Veterinärtidning. 2006, 58: 19-25.

Nevala M, Taponen S, Pyörälä S: Bacterial etiology of bovine clinical mastitis- data from Saari Ambulatory Clinic in 2002-2003. Suomen Eläinlääkarilehti. 110: 363-369.

Acknowledgements

The Estonian Ministry of Agricultural is acknowledged for financial support (research project No 10043VLVL)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

PK carried out the study, compiled the results and drafted the manuscript, BA participated in data collection and coordinated the laboratory analysis, TO participated in designing the study and statistical analysis of the data, AK performed bacteriological analysis, and KK coordinated the study. All authors were significantly involved in designing the study, interpreting data and composing the manuscript.

Piret Kalmus, Birgit Aasmäe, Age Kärssin, Toomas Orro and Kalle Kask contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kalmus, P., Aasmäe, B., Kärssin, A. et al. Udder pathogens and their resistance to antimicrobial agents in dairy cows in Estonia. Acta Vet Scand 53, 4 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1751-0147-53-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1751-0147-53-4